The Greatest Hoax, "Just Passing Through"

Eyes on the prize

We make fun of millennials for — well, for everything really, and rightly so, they’re awful, but especially for their “everyone gets a trophy” culture. (Before you get upset about this, millennials, please note that I don’t care. I’ve got problems of my own right now. I’m not your mom and I’m not really interested in your issues or feelings. Sorry. I promise you’ll get over it.) Given how things are going these days, though, I can kind of see the appeal. I, for instance, think we should all get a trophy for every goddamn week we manage to make it through now. I want a little ribbon for each day, a trophy for the week, an awards dinner for every month and a fucking statue if I make it through a year. These are, at this point, real achievements. Anyway, it’s trophy day. Congratulations, I am genuinely proud of you. I cannot hand out any hardware, but here’s a very good song (pay attention to the build, which is sedate but worth it) and my declaration of admiration for your tenacity. Enjoy.

We Need More Time To Mourn

Julia Cooper’s ‘The Last Word’

Not too long ago, I was late to a memorial service for a family member because I had to be at work when it started. When I arrived, the deceased’s son was just finishing up his eulogy. There were a few more speeches, the evening prayer, and some food, but I didn’t have much time to reflect on the death. Life kept getting in the way. It was a few more days until the enormity of the loss hit me.

In the era of late capitalism and distraction, it’s hard enough to find time to think. It’s harder still to find time to think about things you’d rather not think about. Death and loss take time to process, but my smartphone and the labor it demands give me easy ways to give that time away. Instead of thinking about the absence of an important person in my life, I allowed the space in my brain to be occupied by the nagging unanswered email, the scandals of the orange man, and the flashes of other undone things that needed to be done.

There are formal ways people reflect on death, like eulogies and obituaries. They’re traditions that give us a structure to sit and write, and therefore think about loss. The Last Word: Reviving the Dying Art of Eulogy by Julia Cooper is a work of cultural and literary criticism that looks at mourning, eulogies, obituaries, and the other ways people talk about death. As Cooper notes, reflecting on death, because it takes time and because it is not an efficient process, is counterintuitive under capitalism. No one gets paid to write eulogies. As Cooper writes, “being absorbed in your grief holds no social value” because we’re not producing or distributing anything of economic worth.

In secular society, grieving is narcissistic. It does no good for the dead — they’re gone. Grieving exists for the living to move on. And while grieving can be a shared, communal activity, it is an ultimately private thing, because the totality of a person cannot be fully comprehended by another person, no matter how much you try to communicate it. Language is useless here.

As a selfish activity, grief has no economic value. But as a shared one, it can be commodified. Mourning a celebrity online is a way to trade appreciative notes about how much Prince’s music or Vilmos Zsigmond’s images affected you, but they’re also a way to stake social capital, to orient you and your tastes in a particular position. You have a duty to instantly tweet out how much David Bowie’s work meant to you, working under that assumption that performing that duty is a form of mourning. But joining the chorus without reflection makes you just one voice among many saying the same thing: that you are sad, and that you have no individual relationship with the dead worth contemplating. The mourning masses are a homogenized voice that shout “I am sad!”

Many of us will know of more dead celebrities than we know of dead people who were personally close to us. Our experience is a world away from those of the people who were actually close to Bowie — a man who was privately dying for a year — and who require personal time to mourn and comprehend an enormous gap in their lives. Leonard Cohen was buried and mourned by his friends and family days before the rest of the world learned of his death. By confusing tweeting and actual, individual grief, we think we have some sort of connection. But mourning a celebrity is one-sided. Not that regular mourning isn’t — you’re not going to get a response from the dead. But with a celebrity, the intimacy of whatever you felt never existed on the other side.

Cooper spends a lot of time writing about the death of Princess Diana. It’s an event that predates Web 2.0 social networks, but Diana, whose funeral was one of the most-watched events in history, represents the commodification and de-individualization of mourning like no one else in history. Upon her death, Diana’s public image was abstracted. She became an idea — a moral fable — rather than a human being. The first official act to commemorate her death was to put her face on a £5 coin.

At Princess Diana’s funeral, Elton John performed an updated version of “Candle in the Wind” that became one of the best-selling singles of all time. The profit went to a memorial for Diana’s death, which hundreds of thousands of people also donated to, not sure what else what to do with grief. “Candle in the Wind” was first written as a tribute to Marilyn Monroe; by repeating it, John turned what could have been a singular expression of grief into something bland and universally applicable. “John treated his Diana tribute single like a rare commodity, but a commodity nonetheless,” Cooper writes.

In the scale of the mourning following Diana’s death, the woman herself was lost, as Cooper says. “There was a tendency in the wake of Diana’s death to search for sites already loaded with meaning and to mourn her there — to layer her death atop other established histories. That is, to grieve her in cliché.” The permanent monuments to Diana are in places that have little to do with the life Diana lived. “No one knew who Diana really was, so they pasted her image onto other recognizable images that already held meaning and cultural value,” as Cooper writes, much in the same way that John treated “Candle in the Wind.”

Public, mass-scale mourning events are older than Diana’s funeral, of course. Cooper traces a line back to Lincoln, also now more myth than man, who was murdered at a time when the nation had sufficient means to communicate quickly over long distances. Lincoln’s coffin took a seven-state tour, traveling by train and stopping in 180 cities before his corpse was buried in Springfield, Illinois, three weeks after his death. At the cadaver’s New York City stop, a military procession took up five blocks on Broadway “while the curbs of sidewalks disappear under the crowds.” Dispatches were wired around the country and pictures were taken with something called a stereoscope. Grieving always kept up with technology.

The labor of mourning is done in private, but grief is still inextricable from one’s public life. Eulogies and obituaries are both written in silence, each form grappling with a person’s life, attempting to render it in prose. Each has its own platform — the eulogy is spoken while the obituary is published in print. The two are also composed by people who have different relationships with the private and public dynamic of mourning. An obituary is a journalistic assessment and does not require any kind of meaningful emotional relationship between the journalist and the dead (an exception is Norman Mailer, who wrote his own obituary, because of course he did). A eulogy, though, is spoken by someone close to the deceased. It is not meant to cover an entire life, and it is addressed to a select few rather than anyone who picks up the paper. It’s a translation of a private expression of grief for a circle of fellow mourners. Giving a eulogy is a group activity.

In this public-private dynamic of mourning, religion plays a central role for most people. But Cooper doesn’t do much to address religion. She isn’t a particularly religious person, and she describes her mother’s turn to Christianity before her death as “a last-minute garment she wore in the final few months of her life — like one might cling to a comforting blanket, devoid of any real healing properties, but still therapeutic.”

Cooper’s discussion of religion in The Last Word is understandably through her relationship with her mother. She doesn’t talk about the rich bodies of writing from theologians on the subject of death. She is more interested in exploring the subject through her individual experience. She writes about an old photograph of her mother playing tennis that reminds her “just how long-ago that instant is now,” and reflects on a grocery list she found in the pocket of a sweater that she keeps because she doesn’t “want to forget what her handwriting looks like” and reminds her of “the constellation of tiny decisions that made up her life.”

But by confining the parameters of that discussion, Cooper neglects the important ways that religion shapes our experience of talking about death and dealing with grief. I’m Jewish, so I can’t speak too much about how Christians mourn their dead. But in Judaism, thousands-year-old traditions like sitting shiva and saying Kaddish form a structure to mourning and remembrance that offers meaning, solace, and acceptance. The religious structure is a sanctuary from late capitalism and its discontents. Because I turn my phone off in shul, and because I recognize a higher power, I have an alternative structure of life to enter that late capitalism cannot easily interrupt, if only for a few hours. Grieving is also a communal experience — to say the Mourner’s Kaddish, or pray during a shiva, one needs a minyan of ten people, which may be comforting but doesn’t allow for the same private wrestling one needs to process a death.

This is not to say that religious structures are, in any way, enough. Cooper isn’t dismissive of religion in particular. She’s skeptical that traditional structures for mourning are adequate at all. She uses the “acculturated rules of funeral decorum” to explain the problems with eulogies. Cooper cites the example of Jacques Derrida who, at the funeral of his friend and fellow philosopher Louis Althusser, apologized for giving a eulogy: “Forgive me, then, for reading, and for reading not what I believe I should say — does anyone ever know what to say at such times? — but just enough to prevent silence from taking over.” (Althusser murdered his wife, so I’m sure the silence was deafening.)

Cooper finds Derrida’s difficulty with eulogizing comforting. If Derrida can’t write a proper eulogy, then maybe, she says, the structure of mourning just isn’t good enough. It’s too neat a format to speak the necessary “ungroomed thoughts” about loss:

“There seems to be words that one ought to say at a funeral — presumably the clichés about heaven gaining another angle, a life fully lived, a candle extinguished too soon, etc. — and that no one (even those who fall into cliché) really has the right words for the occasion of death … It should come as a comfort because it confirms that eulogizing is at its absolute core an amateur’s art.”

One of Cooper’s most admirable qualities is that she refuses to see loss as a rote experience. For her, each death is uniquely devastating. Even while reading Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, surely one of the most harrowing chronicles of loss published this century, Cooper diverges from “Didion’s notion that even though grief is disarming, disorienting, and can feel at times fantastical, it is a process that ought to come clear at the end.” To her, Didion’s model of grief is a hoary, Kübler-Ross-like template that seems too efficient. Death is messy; any kind of thinking that makes it seem easy is suspect.

The merits of structured, homogenized methods of dealing with death — like religion — are up for debate. In the least, it’s an individual choice. But whether public or private, mourning is an experience everyone deserves. We live in a time where distractions encroach on our time and bandwidth. Carve out some space for mourning.

Jacob Shamsian is a reporter at INSIDER. He’s also written for Business Insider, GQ, The New Republic, Entertainment Weekly, Time, and Modern Farmer. You can find him on Twitter, where he’s thinking about death.

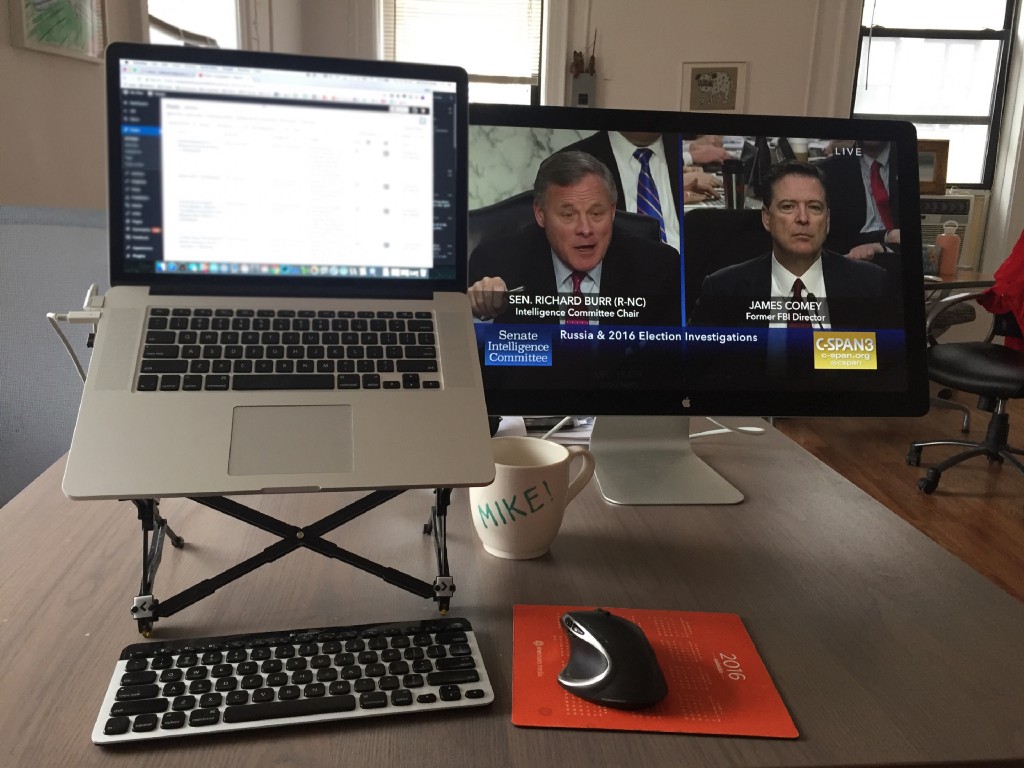

Thank You For Your Service

In a moment of crisis, a hero emerges: You.

Now that the public part of the Comey hearing has ended I want to offer an acknowledgement of all the time you spent tweeting about it. Please do not mistake my brevity for a lack of appreciation — far from it! It is more an affirmation that I understand how busy you are with all your other responsibilities, and what a sacrifice it must have been for you to tear yourself away from them, knowing that you would have to make up all the lost time later.

In any event, I hope you will allow me to be the first to offer my undying thanks for all the work you did just now. I cannot overstate how valuable it was that we had you there to provide commentary on social media during this moment of national significance. Your voice in particular rose above the din to add unique and irreplaceable value to a subject about which many of us would have been confused or even clueless without the impressive guidance you brought to bear.

I know you are the modest type, and you’ll be embarrassed by all this praise, but before you brush it off with self-deprecating asides about just being part of the conversation I want to say, no, that’s not what happened, and we all know it: You, sitting there tweeting even though you knew thousands of other people were doing and saying the same things — frequently faster and often with more precision and wit — were the hero that America needed at moment where it never needed a hero more.

Now I know you’re anxious to get back to everything you put off so you could come to us in our hour of desperation, but please do so knowing that our gratitude goes with you and will never die. This country owes you a debt it can never fully repay, but will try to a little bit each day from here on out. Take a bow. You’ve earned it.

Just Get On A Plane And Go

Guatemala Diaries

Sunday my friend M. was like “Do you want to go to Guatemala on Wednesday?” It wasn’t very expensive, so I decided I would go.

There is this thrill one gets from taking a trip at the last minute, which is probably at least as good as the trip itself. Between the moment I bought the ticket Monday morning and heading to the airport Wednesday morning, I was charmed by myself that I was the sort of person who just up and decided to go to Guatemala at the last minute. And of course people rewarded me with a lot of: “Dude, you’re just like, going to Guatemala, you’re amazing!” and “Whoa, I want to be you when I grow up!” But the fact that I can just randomly go to Guatemala doesn’t mean that I am brave or interesting or adventurous. It just means that I happen to exist at an intersection of mildly privileged semi-aimlessness and a determination, against all odds, to avoid true employment.

My travelling companion has a very demanding job that involves a lot of epic disappointments. These disappointments befall not him but the people he works for, and they are often life-ruining, and almost always unfair. M. certainly has moments of being weighed down by his cynicism but is perhaps as often held aloft by it, giddily aware that possessing freedom, health, and solvency all at once is just a fluke. This vacation was his first in a long time. “Get ready to partyballz,” he texted me after I bought my ticket.

We were flying out of Sacramento, but we had to stop at the Placer County Library to return a 10-DVD recording of the history of the Battle of Waterloo. M. complained about the historian’s account. “He tries to pretend like he’s objective, but every time a French person gets killed he is like totally stoked,” he said. “Plus, he acts like Wellington is so perfect and doesn’t really give Napoleon any credit.” I said I knew almost nothing about Napoleon. M. explained that he had come to power during the French Revolution. “I didn’t even know that,” I said. “Is that bad?”

“You know that everyone dies,” M. said. “That’s enough.”

We talked about Merle, the dog we share. “I wish we could bring her,” I said.

“She makes too many vomiting noises,” M. said. “And then sometimes she actually vomits.”

“I know,” I said. “But I would give anything for a photo of Merle standing on top of a Mayan ruin looking bored out of her mind.” I have been to Mayan ruins before, outside Mexico City, an experience I failed to find moving. Part of the reason I had agreed to go on this trip was to see if there had been something wrong with those ruins, or with me.

On the plane I forgot to turn off the video thing on the seat in front of me and was treated to a series of before and after pictures of people who had jaw reconstruction. They all looked pretty much the same to me. I thought about a recent New York Times article that reported as news the fact that people find intelligence sexually attractive. It was the kind of thing you read and then wonder if you might actually just be dreaming that you are alive. I wondered how much more awesome a new jaw could make your life if your old one was not that bad.

The woman sitting next to me read Cooking Light and every few minutes photographed a recipe with her Android. I noticed that she had the kind of ill-defined chin one might reconstruct if so inclined. Then I wondered if my own, very slightly hyper-defined chin might benefit from reconstruction. The flight attendant handed me a packet of savory snack mix, which is something I never eat but really love, and I poured the contents of it into my mouth, already — according to my very modest goals — partying ballz.

A Poem By Melissa Stein

Polar Vortex

The air pinned us like a two-ton

duvet. We painted all the walls

blue. We sipped icebergs

to cool down. When it got really bad

we imported San Francisco fog

and tethered it over the pool.

Small benevolent wild creatures

joined us, splaying out their bellies

on the tiles, taxidermied by the heat.

At least we were unpelted. And while

we’d extract our own kidneys

with a dull pair of left-handed scissors

before suffering another body within twenty feet

of our parboiled flesh, the stupefaction

cultivated erotic dreams so robust

and depraved we fell to our knees

in gratitude every newly

unbearable morning.

Melissa Stein is the author of the poetry collection Rough Honey, winner of the APR/Honickman First Book Prize. Her second book will be published by Copper Canyon Press in 2018. She’s a freelance editor in San Francisco.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Shinichi Atobe, "The Red Line"

Let’s just get to the sleep part.

So many things are happening all the time now but so many things are happening just today! You know where you’re going to be able to hide from it all? Nowhere. You know who’s not going to be annoying? No one. You know what’s not going to make you want to die? Nothing. All you can do is run down the clock until you finally get to sleep again. Even though even sleep has been ruined by everything being horrible now it’s still the only thing we’ve got left that is not all the other things. On today especially let’s take a second to appreciate sleep. Sleep: It’s what you do to not be awake. Okay, good luck out there, you are sure as hell going to need it. Here’s a classic from Shinichi Atobe to get you through. Enjoy.

New York City, June 6, 2017

★ The rain was coming down just hard enough to keep the pavement glossy. Some fatter, louder drops fell on the schoolyard, but they may have just been blown down from the treetops. The rain paused for a while and a drizzle replaced it. At lunchtime, or what would have been lunchtime, it was a forbidding, steady shower. That stopped too, leaving little puddles marking the rhythm of the machine that had torn up the street. Even the rainless interludes were raw and no brighter, and there was always more drizzle behind them.

The Best Personal Essay I've Read In Years

Is the James Comey Statement.

A few moments later, the President said, “I need loyalty, I expect loyalty.” I didn’t move, speak, or change my facial expression in any way during the awkward silence that followed. We simply looked at each other in silence. The conversation then moved on, but he returned to the subject near the end of our dinner.

Bravo. You can read the whole beautiful thing here.

Cosby Coverage To Follow

Just a few suggestions

These people are all there, in Norristown, Pennsylvania, in person. They also happen to be women! There are obviously others—these are just my own personal recommendations.

Diana Moskovitz for Jezebel

Jia Tolentino for The New Yorker

Bill Cosby’s Trial Begins, With the World Barging In

Molly Redden, for The Guardian

Claudia Rosenbaum for Buzzfeed

Stephanie Gosk for NBC News

Bill Cosby heads back to court, escorted by his TV family

Jessica Goldstein at Think Progress