New York City, August 24, 2015

★★★ The air was warm and unmoving. From the office roof, haze spread out below. Awning fabric held and channeled the smell of the respiration of hot vegetables out onto Union Square. A baby down in the subway had an electric fan clamped to the front bar of its stroller. The haze was wearying to walk in. Late in the day, the dinginess of it took on attractive colors. At sundown, pink light flooded high clouds in half of the west, while a lower cloud blocked the remainder.

The Uber Endgame

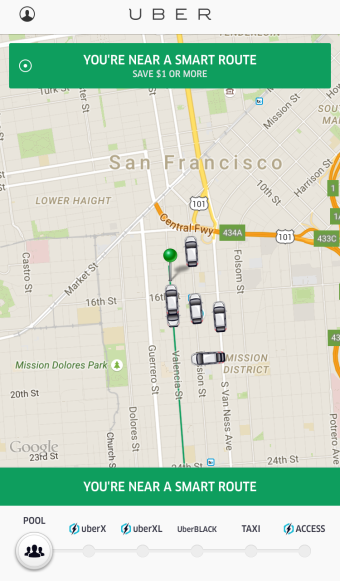

In San Francisco, Uber recently began testing what it calls “Smart Routes,” TechCrunch reports:

Rather than hailing an Uber directly to your door, UberPool’s map shows a green line overlaid on a major artery street nearby. If you’re willing to set your pickup location anywhere along these Smart Routes, Uber will compensate you with a discount of $1 or more off the normal UberPool price. In some cases that means walking a few blocks to your pickup spot. A little less convenient, a little cheaper.

Several weeks earlier, Uber began testing what it calls “Suggested Pickup Points”:

When dragging the pickup pin, the feature explains that passengers can “save time at these locations”, and shows places nearby where it would quicker for the driver to pick them up. Users can drop their pin on these green dots, see the address, and then walk there to shorten their wait time. … For example, at the San Francisco Giants’ AT&T; ballpark above, Uber suggests people head to one of the corners outside, rather than in the middle of the block where traffic rushes and there’s nowhere to pull over. If you’re in an one-way alleyway, Uber recommends you head out to the next main street.

And a few months ago, CEO Travis Kalanick mentioned something called a “Perpetual Trip” which would “allow drivers to pick up and drop off passengers continuously along the way,” taking its UberPool car-pooling service to its logical conclusion, an unbroken chain of rides.

TechCrunch’s Josh Constine compares Smart Routes to another “ride sharing service, Loup, which pays people to drive their cars and pick people up on bus-like routes through a city, and Chariot which does the same but with big vans.” But if you put all of these Uber innovations together — pre-determined routes with fixed pickup points and continuous passenger pickups — it sounds remarkably like a gently optimized version of currently existing mass transit, one of the services that Uber is attempting to d i s r xu p t. (It is telling though that Constine notes that one of Uber’s Smart Routes runs “up Fillmore St. from Haight St. to Bay St. in the Marina, which the Bay Area’s BART service doesn’t cover,” when the route is directly covered by the SF MUNI 22 bus, which runs every eight minutes according to Google Maps.) But it’s not surprising at all that Uber and Lyft continue to independently arrive at features that so closely resemble public transit that it seems like self-parody:

It turns out that mass transit is extremely efficient at moving around large quantities people and even, in some cases, getting them to “move past car ownership” en masse. What Uber and Lyft are building toward, in other words, is best understood as a privatized mass transit system built on top of public roads.

What’s remarkable, perhaps, is that for all of Uber and Lyft’s innovations, beyond a certain scale, they have yet to devise wholly unique or vastly differentiated solutions to the problems of moving people around in large cities. (This is not to downplay at all the enormous potential efficiencies of transit that is networked and dynamically responsive to rider demand, but only to point out that if public transit agencies were also beholden solely to people who own smartphones and mostly lived in relatively affluent areas, one could more easily imagine the MTA or Muni or the TLC making such upgrades.)

One of the more subtle underlying issues with the rise of Uber is the company’s slow siphoning of the political will to fix existing — or build new — public transit infrastructure in major cities. In Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America, Princeton Professor of Politics Martin Gilens shows that — as he put it in an article with Northwestern Professor of Decision Making Benjamin Page — “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while mass-based interest groups and average citizens have little or no independent influence.” As the wealthy — and, as the prices of Uber and Lyft fall, the slightly less so — essentially remove themselves from the problems of existing mass transit infrastructure with Uber and other services, the urgency to improve or add to it diminishes. The people left riding public transit become, increasingly, the ones with little or no political weight to demand improvements to the system.

And if it seems unreasonable to imagine a scenario in which the mass adoption of Uber leads to a potential death spiral for public transit — and the true privatization of mass transit — in some cities, one need only consider how many public services have emerged and then been sustained precisely because they aligned with the particular vision of economic elites during a given time period. (For instance, in the case of Obamacare, the interests of the poor, who need universal healthcare, have become aligned with the rich, whose companies have, in recent years, increasingly relied on independent contractors or part-time labor rather than full-time employees to reduce costs and increase profits; Obamacare has effectively accelerated the erosion of the concept of full-time employment in its fulfillment of one of the the former social obligations of employers. Put another way, why hire an employee and pay for their healthcare and social security when you can hire an independent contractor and let the worker and the government split the cost?)

An exemplary case of Uber’s re-direction of the political will of its base was its total victory over Mayor Bill De Blasio’s hapless and deeply stupid campaign to limit the company’s growth in New York City — some of the final blows coming from celebrities (and even some business journalists!) tweeting messages written by Uber on its behalf. Would it be crazy to wonder what would happen if those same people mounted a similarly forceful campaign to get Governor Cuomo to clean out and fully fund the MTA to, say, make the L train less terrible?

The subtext of Uber’s new products having the look and feel of a slightly shinier version of mass transit is, of course, that Uber wants to be privatized mass transit. In Uber’s grand vision, no one owns cars because nearly everyone is taken everywhere in a driverless, electric, omnisciently networked Uber conveyance that arrives precisely when it is needed for a price cheap enough that for many people it feels free (but is just enough to make a profit, since one day, as unimaginable as it seems, the venture capital will run out). This is why Uber earnestly speaks of ending car ownership, taking cars off the road, and helping nurses commute to and from night shifts in the Bronx at two in the morning.

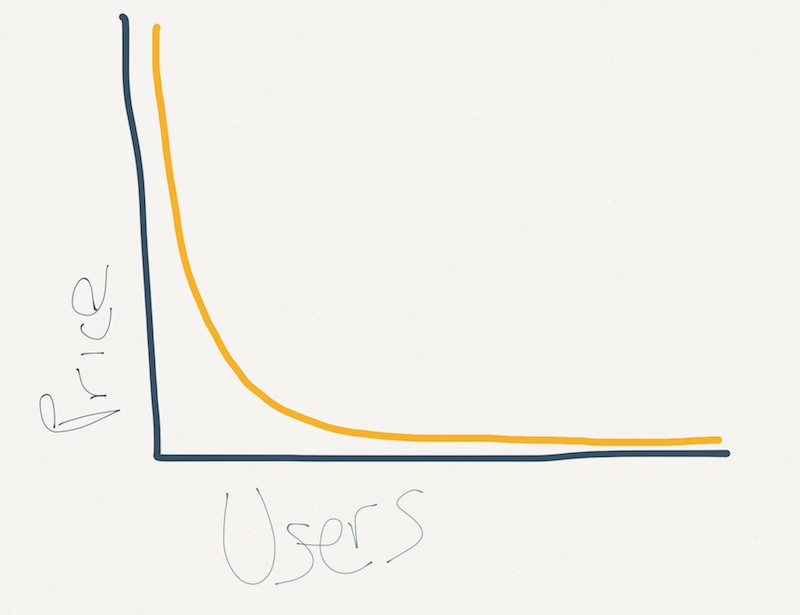

In general, the cheaper Uber is, the more mass it will become, and the more mass it becomes, the cheaper it can get — particularly once its cars have become driverless, as Kalanick predicts in the next fifteen years or so. This is how Uber transforms itself from a luxury to a basic, indispensable utility. But until Uber’s cars become driverless, it has at least one cost that is relatively fixed: labor. Uber must pay its drivers a living wage (or close enough to it). The fewer drivers that Uber must pay to meet increasing passenger demand — by putting more passengers in vehicles at once and minimizing gaps between rides — the more effectively it can hold down prices, fueling growth in both the number of users and the number of trips they are likely to take, making itself more and more integral in people’s lives. (Not incidentally, more efficiently packing each Uber vehicle makes surge pricing, which customers unduly loathe, less frequent, also encouraging people to use it more frequently.) This is why and how UberPool, Smart Routes, and perpetual rides work — and why and how Uber products have progressed, in the order that they have, from Uber Black to Smart Routes. (This is where a VC might point out that this is how all technological innovation works, trickling down from the elites to the masses.)

Let’s grant that Uber’s vision will come true. (It might!!!!!) While zero car ownership will undoubtedly and unremittingly be a net social good — can’t wait until driving is something one does for fun, ban cars! — and while perhaps nearly everybody will be able to afford Uber the Utility, what happens in the time between now and the Ubertopia? Capitalism may eventually provide everything for everyone (so we keep hearing!), but what about the people who can’t quite afford to Uber everywhere during the years when it costs more than public transit — which becomes broken and neglected as a large portion of the population effectively abandons it and no longer demands its maintenance, much less improvement? I suppose politicians could campaign on a platform for affordable Ubers — much like the price of putting up luxury housing in New York City these days, perhaps eighty percent of riders pay the market rate so that the twenty poorest percent need only pay what they can afford. It’d work better than De Blasio’s campaign to cap Uber, right?

Giph by Jalopnik; screenshot of Smart Routes by TechCrunch

Yumi Zouma, "Right, Off The Bridge"

Our brief flirtation with economic collapse brings to mind an always-interesting three-drink question: If the various networked tradebots were to blow up the markets right now, setting of some sort of chain reaction that pundits would assure us was obvious in retrospect, which music would get dropped from the public consciousness? Are there genres or sounds that thrive at six percent unemployment but die at ten? Does all this great dreamy electronica seem silly, then? Does…nu metal come back? Guess we’ll have to wait a little longer to find out.

Happy National Duck Out For A Drink Day 2015

WHEREAS work is long, boring and especially difficult to take during the summer months when you could be outside, particularly when you consider how awful winter has been lately and will be for the rest of our lives and you’re starting to realize summer is almost over, and

WHEREAS contemporary human existence is a mostly unrelenting series of trials and tribulations of varying degrees of unpleasantness, none of which means anything in the end, the only reasonable temporary solution that has yet been discovered for being alcohol, and

WHEREAS life is largely designed and directed by forces beyond your control and your lack of real agency may be the most frustrating thing about work, and

WHEREAS a national day of celebration in which colleagues sneak away from the office to nearby bar to have a few quick drinks to both alleviate their pain and briefly exercise some sort of power over their own time has been shown over the years to be one of the few bright spots in a calendar otherwise filled with soul-crushing ennui,

NOW, THEREFORE, I, Alex Balk, creator of a holiday designed to allow everyone to blow off just a few minutes of goddamned steam with a couple of shots or beers or maybe even a craft cocktail if that’s the kind of thing you’re into and you don’t mind dropping $17 on something that a $5 slug will have the same effect as, do hereby proclaim Tuesday, August 25th, as National Duck Out For A Drink Day throughout the United States of America,

URGING AND DIRECTING all within its borders to take a few moments at some point during the day to run out alone or with colleagues and enjoy the temporary relief alcohol has to offer, remembering especially that if you go to the bar during work, it’s like they’re paying you to drink.

DECLARED AND AFFIXED BY ME HERE ON THE INTERNET, LIKE AND SHARE ON FACEBOOK AND INSTAGRAM AND TWITTER OR WHATEVER IF YOU FEEL LIKE IT (SOCIAL IS PRETTY IMPORTANT THESE DAYS), IF YOU’RE SOMEONE WHO DOESN’T OR CAN’T DRINK I GUESS JUST SNEAK OUT AND HAVE A SODA TO STAY WITH THE SPIRIT OF THINGS, REMEMBER TO BRING MINTS SO YOU DON’T GET FIRED WHEN YOU GET BACK, THANKS FOR ENJOYING THIS HOLIDAY EVERYONE, IF YOU DO DRINK DON’T DRIVE, ETC. Enjoy.

New York City to Maplewood, New Jersey, to New York City, August 23, 2015

★★★★ The sun outperformed the forecast in the newspaper, flooding the face of the apartment block to the west, drawing people out onto their balconies in a morning theoretically at risk of showers. Bright yellow-green plant life was growing on the flat waters by the Turnpike, like gold mottling on a decorative mirror. The roads into the suburbs were clear, the air clean, the passage from indoors to out uncomplicated. The three-year-old worked himself into a sweat going from basketball to tee-ball to kiddie car to balance bike. The remains of a water battle on the asphalt of the driveway dried up quickly. The late clouds over the Turnpike were extravagant, a row of dramatic grays stacked on a row of magenta. Back in the city, from 27 floors up, the colors flared even brighter — purple topped with pale pink, above a background of flaming gold.

Reminder: Tomorrow Is National Duck Out For A Drink Day

It seems like just yesterday that I declared August 25th to be a national holiday where all observers took time to sneak out of their jobs and have a quick nip or two, but it turns out it was five years ago. Where did the time go? Fuck if I know. It’s 2015 now and nothing new makes sense to me, particularly this Internet we have going on these days. If I understood it any better I would set up some kind of hashtag like #nationalduckoutforadrinkday or however the hell you do it, that seems like a lot of characters, and like an Instagram thing where you could all post pictures of yourselves drinking during office hours with artfully blurred faces or whatever, but I don’t and I’m not willing to learn so instead what I will do is just remind you that tomorrow, August 25th, is National Duck Out For A Drink Day. You and your colleagues should make plans now for how you will be getting your holiday on tomorrow. A late lunch? An early exit? An “off-site meeting” around 2? The choice is yours! Have fun with it! Like and share, or whatever you kids do nowadays. But the important thing is that you celebrate. Again, the most important thing to keep in mind is this: If you go to the bar during work, it’s like they’re paying you to drink. Remember the holiday and keep it holy.

Literary Magazines for Socialists Funded by the CIA, Ranked

by Patrick Iber

In May of 1967, a former CIA officer named Tom Braden published a confession in the Saturday Evening Post under the headline, “I’m glad the CIA is ‘immoral.’” Braden confirmed what journalists had begun to uncover over the previous year or so: The CIA had been responsible for secretly financing a large number of “civil society” groups, such as the National Student Association and many socialist European unions, in order to counter the efforts of parallel pro-Soviet organizations. “[I]n much of Europe in the 1950’s,” wrote Braden, “socialists, people who called themselves ‘left’ — the very people whom many Americans thought no better than Communists — were about the only people who gave a damn about fighting Communism.”

The centerpiece of the CIA’s effort to organize the efforts of anti-Communist artists and intellectuals was the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Established in 1950 and headquartered in Paris, the CCF brought together prominent thinkers under the rubric of anti-totalitarianism. For the CIA, it was an opportunity to guarantee that anti-Communist ideas were not voiced only by reactionary speakers; most of the CCF’s members were liberals or socialists of the anti-Communist variety. With CIA personnel scattered throughout the leadership, including at the very top, the CCF ran lectures, conferences, concerts, and art galleries. It helped bring the Boston Symphony Orchestra to Europe in 1952, for example, as part of an effort to convince skeptical Europeans of American cultural sophistication and thus capacity for leadership in the bipolar world of the Cold War. By purchasing thousands of advance copies that it gave away for free, the CCF supported the publication of many of the era’s anti-Communist classics, such as Milovan Djilas’ The New Class. But its most impressive achievement was a stable of sophisticated literary and political magazines. The CCF’s flagship journal was the London-based Encounter, but it also published Preuves in France, Tempo Presente in Italy, Forum in Austria, Quadrant in Australia, Jiyu in Japan, and Cuadernos and Mundo Nuevo in Latin America, among many others.

Through the CCF, as well as by more direct means, the CIA became a major player in intellectual life during the Cold War — the closest thing that the U.S. government had to a Ministry of Culture. This left a complex legacy. During the Cold War, it was commonplace to draw the distinction between “totalitarian” and “free” societies by noting that only in the free ones could groups self-organize independently of the state. But many of the groups that made that argument — including the magazines on this left — were often covertly-sponsored instruments of state power, at least in part. Whether or not art and artists would have been more “revolutionary” in the absence of the CIA’s cultural work is a vexed question; what is clear is that that possibility was not a risk they were willing to run. And the magazines remain, giving off an occasional glitter amid the murk left behind by the intersection of power and self-interest. Here are seven of the best, ranked by an opaque and arbitrary combination of quality, impact, and level of CIA involvement.

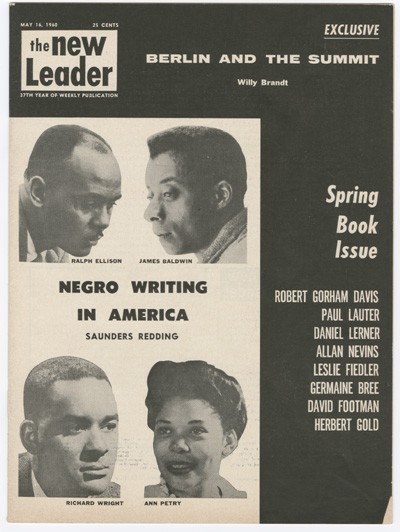

7. The New Leader

The New Leader was founded in the nineteen twenties as a voice for American socialism, but by the dawn of the Cold War, it focused incessantly on establishing the totalitarian and imperialist character of the Soviet Union. During The New Leader’s heyday in the late forties and early fifties, its editor was Sol Levitas. The New Leader’s relationship with the CIA wasn’t always easy; the CIA actually thought that Levitas’s anti-Communism was too ferocious, unrelenting, and “conservative.” The New Leader argued consistently that Soviet society was totalitarian in nature and Communism everywhere was controlled by the Kremlin, while the CIA wanted a more moderate and “sophisticated” voice that would appeal to the European left. In spite of its strident anti-Communism, The New Leader remained progressive in the context of U.S. domestic politics; it was one of the first publications to publish Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

6. Der Monat

Der Monat (“The Month”) was a German magazine founded in 1948 by New Yorker Melvin Lasky; the magazinewas his attempt to put his desired politics of “cultural freedom” into action. The year before, Lasky had caused a stir at the First German Writers’ Congress when he brought up the persecution and suppression of writers in Russia. He argued that those in the West should have sympathy for Russian writers, who had to continually worry about secret police actions and that shifting party doctrine might brand them overnight as “decadent counterrevolutionary tools of reaction.” Originally published under the authority of the U.S. military government in divided Germany, it became an important template for the magazines of the Congress for Cultural Freedom and was later incorporated into that network. Many have suspected Lasky himself of being a CIA agent, he denied it to the death.

Der Monat published the work of Theodor Adorno, Arthur Koestler, Hannah Arendt, Heinrich Böll, and Thomas Mann.

5. Kenyon Review

Probably the finest literary magazine in American history, the Kenyon Review was founded by John Crowe Ransom in 1939. The intellectuals and CIA officers who ran the Congress for Cultural Freedom loved Ransom, and used him and his literary networks to locate promising students and literary friends that it could recruit to work for it. Even Ransom’s technique of “New Criticism,” seen as a quintessentially conservative Cold War form of analysis because it eschewed examination of the social and political context of literary works, has sometimes been compared to the work of espionage, by which careful reading can unearth hidden plans and meanings.

A partial list of the nearly insuperable roster of the Kenyon Review’s authors includes Robert Lowell, T.S. Eliot, Flannery O’Connor, Thomas Pynchon, Nadine Gordimer, Randall Jarrell, and Joyce Carol Oates. It, as well as others, including the Hudson Review, the Sewannee Review, Poetry, Daedalus, Partisan Review, and The Journal of the History of Ideas, had hundreds and even thousands of copies purchased for distribution abroad by the Congress for Cultural Freedom, and sometimes received grants more directly. This was significant help for a small magazine; Kenyon Review had to close for a decade beginning in 1969, just a few years after revelations of CIA involvement forced such support to be discontinued. Robie Macauley, who had been recruited by the CIA some years earlier, succeeded Ransom as editor of the Kenyon Review.

4. Paris Review

Of all the publications on this list, the Paris Review may be the one with the weakest connection to the CIA. Like the Kenyon Review, the Paris Review is one of the twentieth century’s finest literary magazines. Edited by George Plimpton, it published the likes of Italo Calvino, Samuel Beckett, Philip Roth, V.S. Naipaul, Jack Kerouac, Donald Barthelme, Jeffrey Eugenides, and Jonathan Franzen. Peter Matthiessen, one of the co-founders of the Paris Review, had been recruited into the CIA and the magazine initially served as part of his cover. But he maintained that the connections ended there, and that the Paris Review was certainly not a part of the Congress for Cultural Freedom. For a 2012 article published in Salon, however, Joel Whitney examined the archives of the Review and found a deeper-than-acknowledged relationship with the CCF and, therefore, the CIA. Some of this was inevitable: They shared a Parisian milieu and had common interests. But the record clearly shows that the Paris Review benefited financially from selling article reprints to CCF magazines. This was far from the CCF’s direct participation in management of Der Monat or Encounter, but the Paris Review did derive some benefit from the CIA, and there is circumstantial evidence that this affected the choices of authors for its interview series. In a way, the Paris Review case shows how difficult it was for “apolitical” highbrow literary periodicals to get through that period of the Cold War without some form of interaction with the CIA.

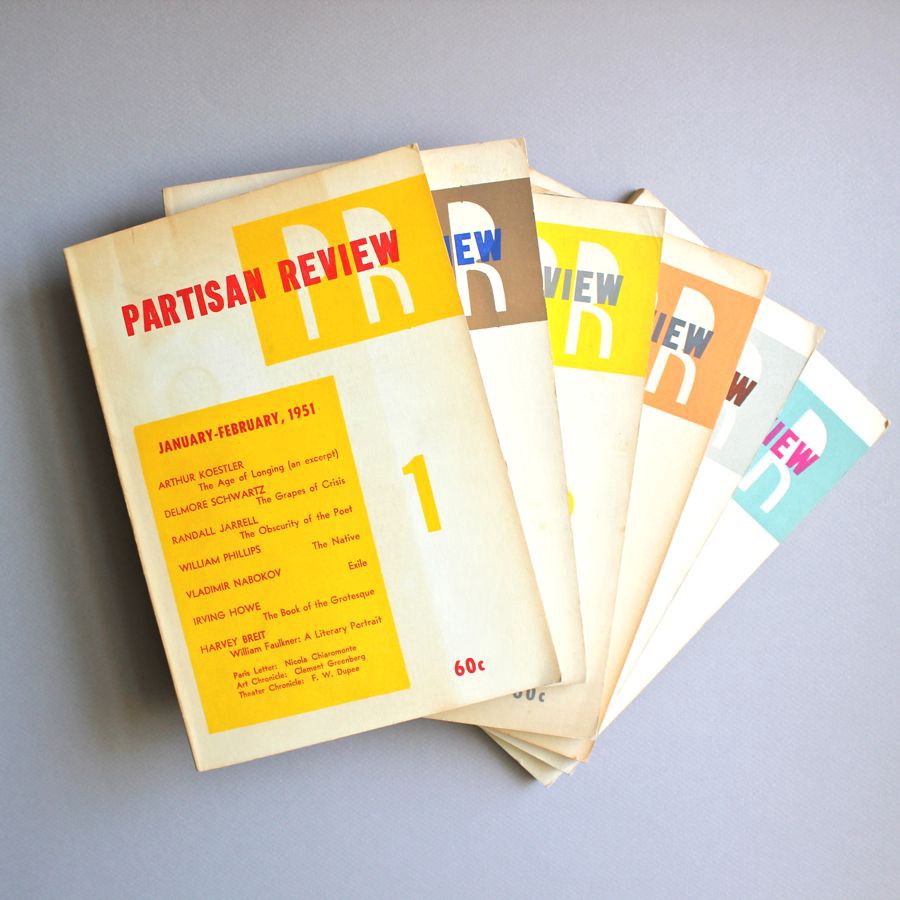

3. Partisan Review

Partisan Review was, for a few short years, one of the finest magazines produced. In the late thirties and early forties, when it was funded primarily by the painter George Morris, it was controlled by an avant-garde group of “literary Trotskyists” interested in fusing cultural modernism with political anti-Stalinism. Delmore Schwarz’s well-known short story, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” was published there in 1937 — and that issue alone contains work by Wallace Stevens, Edmund Wilson, James T. Farrell, Pablo Picasso, James Agee, Mary McCarthy, and Dwight Macdonald. George Orwell was another frequent contributor, and Partisan Review was first to publish many classic essays of criticism, including Clement Greenberg’s “Avant Garde and Kitsch,” and Susan Sontag’s “Notes on ‘Camp.’” The magazine, like so many, peaked early in its publication history. By the time that it received CIA support in the nineteen fifties, it had lost some of its initial energy, and its politics were growing increasingly “neoconservative,” although it continued on as a “little magazine” until 2003. (Boston University has made every issue of Partisan Review fully available online.)

2. Encounter

London-based Encounter was considered the crown jewel of the Congress for Cultural Freedom’s publishing program. Created in 1953, Encounter was edited by Irving Kristol and later, Melvin Lasky, while the literary pages were for many years curated by the poet Stephen Spender. It regularly published both British and American writers, including Isaiah Berlin, Mary McCarthy, Hugh Trevor-Roper, W.H. Auden, Daniel Bell, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Bertrand Russell, Stuart Hampshire, and John Kenneth Galbraith. It is often credited with helping shift the British intellectual scene away from socialism and towards an “Atlantic,” pro-U.S. outlook. Edward Shils worked out his ideas of “The End of Ideology” in its pages; C.P. Snow published his essay on the “two cultures” of the natural sciences and the humanities there; and it published Nancy Mitford’s “The English Aristocracy,” the classic essay about “U and non-U” describing differences in pronunciation between British classes. It also helped introduce English readers to authors like Jorge Luis Borges, and frequently featured the witty and erudite anti-Communism of Leszek Kolakowski. (See his “How to be a Conservative-Liberal Socialist” — the founding document of what he describes as “the Mighty International that will never exist,” for a reasonable distillation of the magazine’s ideology.) Encounter’s strength was such that it survived the CIA scandals of the late sixties and continued publishing on its own into the early nineties. The entire run of Encounter is fully available online.

1. Mundo Nuevo

The Congress for Cultural Freedom’s programs were not limited to Europe, and in the mid-sixties, it was trying to shift its Latin American operation from one that was ineffectively fighting the relatively unimportant pro-Soviet Communist parties of the region to one that would subtly undermine the appeal of Fidel Castro’s Cuba. It closed one magazine, Cuadernos, in 1965, and launched Mundo Nuevo a year later to try to appeal to more left-wing writers. The initial director of Mundo Nuevo, the Uruguayan Emir Rodríguez Monegal, insisted that he was trying to broker peace in the Cultural Cold War and have an honest dialogue about art and politics in Cuba.

Like other magazines affiliated with the Congress for Cultural Freedom, Mundo Nuevo published essays critical of U.S. policy in Latin America and Vietnam. Its usefulness, from the U.S. government’s point of view, consisted in its defense of the responsibility of the artist as an independent critic of power, rather than part of a the machinery of revolutionary social transformation. Cuban intellectuals noted the magazine’s ties to the CCF and refused to participate; nonetheless, in its first few issues, Mundo Nuevo was an extraordinary success. Pablo Neruda, the Communist poet who only a few years earlier had been the subject of a CCF campaign to undermine his candidacy for the Nobel Prize, contributed several poems. There are interviews with Carlos Fuentes and Jorge Luis Borges, and fiction that would be foundational to the “boom” in Latin American letters from José Donoso and Guillermo Cabrera Infante. Most surprisingly, it published an early excerpt from the still unpublished One Hundred Years of Solitude, by Gabriel García Márquez. García Márquez, later famous for his close friendship with Fidel Castro, regretted his contribution when connections to the CIA were soon revealed. Nonetheless, José Donoso, in his memoir of the boom in Latin American literature, wrote that Mundo Nuevo was the “voice of Latin American literature of its time,” and at the center of a major phenomenon in world literature.

Cover photos via Open Culture, Columbia Bibliopolis, Dan Shepelavey, tim rich, Mercado Libre

You You You Talking Talking Talking To To To Me Me Me?

“Philip Glass revisits his parallel lives in 1970s New York — driving a taxicab through threatening twilight streets while emerging as a composer in Manhattan’s downtown arts scene.”

— If you can stand to hear one more thing about New York in the ’70s make it this.

The 10 Best Years Of The 1980s

10. 1984

9. 1988

8. 1986

7. 1989

6. 1983

5. 1985

4. 1980

3. 1982

2. 1981

1. 1987

Solvent, "Pattern Recognition"

How will we know when autumn is approaching here in New York City? A local website warns that fall is imminent, and according to their theories one of the ways by which we are able to tell is that “The sun is setting earlier.” I am as stunned as you are, and also I am wondering how to feed and dress myself. Anyway, here’s some blippy-bloopy music to get us through it. Enjoy.