New York City, August 20, 2015

★★ The clouds were thickly gathered but still individuated, their shade deep but not absolute. Off in the distance, upriver and down were gaps of light; then the light was at hand and the shadows all around. Lower pale gray clouds passed quickly in front of higher white ones. The damp wind gusted. The bright spells were intense but so short that the idea of putting on sunglasses seemed ridiculous. By evening they were gone, the clouds fully closed. A hand out the window at bedtime found rain falling.

When Money Gets Hungry

Earlier this week, Eater critic Ryan Sutton reviewed a pair of relics from another decade, the big-box restaurants Buddakan and Morimoto. The products of a mid-aughts form of conspicuous consumption, they combined an AstroTurfed nightlife aesthetic with the era’s most garish food and drink — Wagyu beef, truffle everything, Iron Chef, signature ______tinis. Nearly ten years after their opening, Sutton finds them horrifically atavistic:

Why does this restaurant exist? Buddakan, along with the Japanese-themed Morimoto, together Starr’s first forays into New York dining, were born in a different era. Both venues, transplants of their Philadelphia originals, opened in 2006, when New York was riding the tail end of its Second Gilded Age.

And for the time, these restaurants served a purpose. Starr’s critically-acclaimed Buddakan was a hipper, younger, clubbier analogue to older, expensive, white tablecloth venues like Mr. Chow, Indochine, and Shun Lee Palace. And Morimoto, with a $200 tasting counter, was the larger, logical extension of the Nobu 57 model, a sprawling den of aioli-slathered rock shrimp and $150 tastings that received three stars from the New York Times. There was enough room for everyone. Until there wasn’t.

The economy started to tank in 2007. And in the years that followed smart restaurants would adapt to our new spending habits, putting the focus on the chef and the food over the maitre d’ and the creature comforts. The Chang Way started to take hold: leaner, meaner, let’s eat at a noisy bar and charge everyone a little bit less. And diners, fueled by the knowledge of a burgeoning class of bloggers, food writers, and uber-locavores like Rene Redzepi and Dan Barber, started to value regional creativity and authenticity over generic extravagances.

The economy has long since recovered for the kind of person who once regularly dined at places like Morimoto. And while there are pointedly direct descendants in the lineage of clubstaurants that continue to combine slightly higher minded food and drink with a scene, like Beauty & Essex, as these extreme consumers have been allowed to shamelessly re-indulge their sizable appetite for casual decadence, many have developed a taste for something else: taste.

Since the end of the recession, Food Culture has metastasized into something truly monstrous — one could (should?) write an entire piece on its growth, as it has flooded TV programming, absorbed vast amounts of venture capital, captured large swaths of discourse (hello), and even assumed incredible priority in urban re-development — so that for people of a certain level of cultural or financial affluence, a rigorously cultivated knowledge of food and restaurants is now regarded as essential to being a properly worldly human. (Or as Eater and Resy co-founder Ben Leventhal once put it to me*, “It used to be dinner and a show — now dinner is the show.”) This is true even at the highest levels of culture and power: Witness Jay-Z’s semi-public excursions to recognized Good Restaurants like Tertulia and Lucali (and investment in the Spotted Pig), or Obama continually popping up at places like Estela, ABC Kitchen, the NoMad, and Blue Hill. It is not enough to eat black truffles shaved over macaroni in an exclusive den of luxury surrounded by fellow Thought Leaders — the truffles must be carved with grace and precision over celery root braised in a pig’s bladder by Daniel Humm.

The most successful and enthusiastic navigator of this new milieu — indeed, perhaps the first to recognize the new dynamics of post-recession downtown luxury dining — is Major Food Group, the restaurant group of Mario Carbone, Rich Torrisi, and Jeff Zalanick. Their original restaurant, Torrisi Italian Specialities, which opened in December of 2009, operated in what Sutton might describe as a post-Momofuku mold — highly credentialed chefs offering inspired food in an environment with unadorned service for moderate prices (in the context of finer dining). Torrisi was a lunch counter serving revelatory sandwiches by day, and at night, a nouveau Italian-American restaurant that hawked a multi-course dinner menu for just fifty dollars. In early 2013, Major Food Group debuted Carbone, a throwback to fifties-era Italian-American restaurants whose single most remarkable feature — besides the sub-continent-sized veal parm — were its prices: thirty-eight-dollar scampi, a forty-eight-dollar antipasti tasting (essentially the same cost as an entire dinner at the former Torrisi Italian Specialties), and fifty dollars for the veal parm (now sixty-four dollars). Pointedly though, as Sutton pointed out, “Your $400 date at Carbone doesn’t begin with anything fancy. No caviar, no foie gras.” There is not much in the way of over-the-top decadence, but there is a twenty-one-dollar Caesar salad and it is incredible.

Carbone was the quiet announcement of a new era in downtown dining. Every MFG restaurant since, while producing food that ranges from merely good to astounding, has been designed around maximum capital extraction from their guests: MFG’s next place, ZZ’s Clam Bar, launched a few months later with a bouncer (sorry, “doorman”), twenty-dollar cocktails and ninety-five-dollar tartare. When Dirty French, a “mongrel bistro” opened in late 2014, Pete Wells noted, “swagger and money have been to Torrisi-Carbone-Zalaznick establishments what blinking lights and sitars are to Sixth Street’s Curry Row.” Besides Parm, the group’s attempt at manufacturing a potential chain, MFG’s most affordable restaurant is Santina, which serves lighter, coastal Italian food in a beautiful glass box tucked under the High Line; its prices seemed tuned to be just forgiving enough to entice tourists left ravenous after an elevated walking tour of New York’s most architectually interesting safety deposit boxes. Meanwhile, the original Torrisi, which had been serving a one-hundred-dollar, seven-course tasting menu, closed at the end of 2014 — to be replaced by a far more exclusive and presumably more expensive restaurant — and, wholly unsurprising, Major Food Group has been chosen to take over the former Four Seasons, the city’s most storied buffet for billionaires.

Felix Salmon, a Fusion senior editor and full-time freelance writer, is strongly opposed to the Major Food Group colonization of the Four Seasons. One of his arguments is that the food is beside the point:

In either case, whether the prime attraction is the people or whether it’s the architecture, the restaurant knows better than to try to show off with its food. Is the food at the Four Seasons Italian? Is it French? Is it American? The answer is: nobody really cares. There’s more than enough reason to dine at the Four Seasons already; the last thing it needs is foodies.

This is probably true for the Four Seasons clientele of the past. But Aby Rosen, the landlord, “want[s] to have the guy coming to the Four Seasons who has the ripped jeans and a T-shirt equally as much as you want the guy with the Tom Ford suit… Because the guy with the jeans, I promise you, has a lot more money.” Whether or not the startup founder now has more money than the investors who originally funded his company, he does care about the food, and not because he is a “foodie,” a term that has become as nearly meaningless as “hipster” or “bro,” for nearly the same reasons: The specific, exasperating traits that it once identified have been fully diffused into culture writ large, from the moderately privileged to the exuberantly wealthy. This is why it’s now nearly as annoying to obtain a thoughtfully engineered eight-dollar fried chicken sandwich as it is to get a reservation to eat an eighty-four-dollar chicken for two at the NoMad — and why the big-box restaurant of yore is just a supermassive black hole of money and taste that now only manages to consume the occasional hapless victim.

Photo by Ludovic Bertron

* This quote, which I hastily pulled from memory, was originally attributed to David Chang, but upon reviewing my reporting notes from that piece, while Chang made lengthy comparisons between dining now and a “Broadway show,” it seems that Ben Leventhal uttered that specific phrase. I regret the error!!!

Nü Metal Bands, Ranked by Nü Metalness

by Michael Macher

56. DEFTONES

55. A PERFECT CIRCLE

54. MARILYN MANSON

53. ROB ZOMBIE

52. MACHINE HEAD

51. FEAR FACTORY

50. GLASSJAW

49. FINCH

48. SYSTEM OF A DOWN

47. INCUBUS

46. FLYLEAF

45. DREDG

44. LINKIN PARK

43. CHEVELLE

42. MUSHROOMHEAD

41. SNOT

40. 36 CRAZYFISTS

39. KID ROCK

38. HOOBASTANK

37. SPINESHANK

36. AMEN

35. DEADSY

34. NOTHINGFACE

33. NONPOINT

32. ULTRASPANK

31. ORGY

30. ALIEN ANT FARM

29. COLD

28. STONE SOUR

27. EVANESCENCE

26. FINGER 11

25. AMERICAN HEADCHARGE

24. PRIMER 55

23. LOSTPROPHETS

22. BREAKING BENJAMIN

21. SEVENDUST

20. STAIND

19. DOPE

18. SOULFLY

17. KITTIE

16. ADEMA

15. CRAZYTOWN

14. DROWNING POOL

13. TAPROOT

12. PAYABLE ON DEATH (P.O.D)

11. HED(PE)

10. PAPA ROACH

9. POWERMAN 5000

8. STATIC X

7. MUDVAYNE

6. GODSMACK

5. DISTURBED

4. COAL CHAMBER

3. SLIPKNOT

2. LIMP BIZKIT

1. KORN

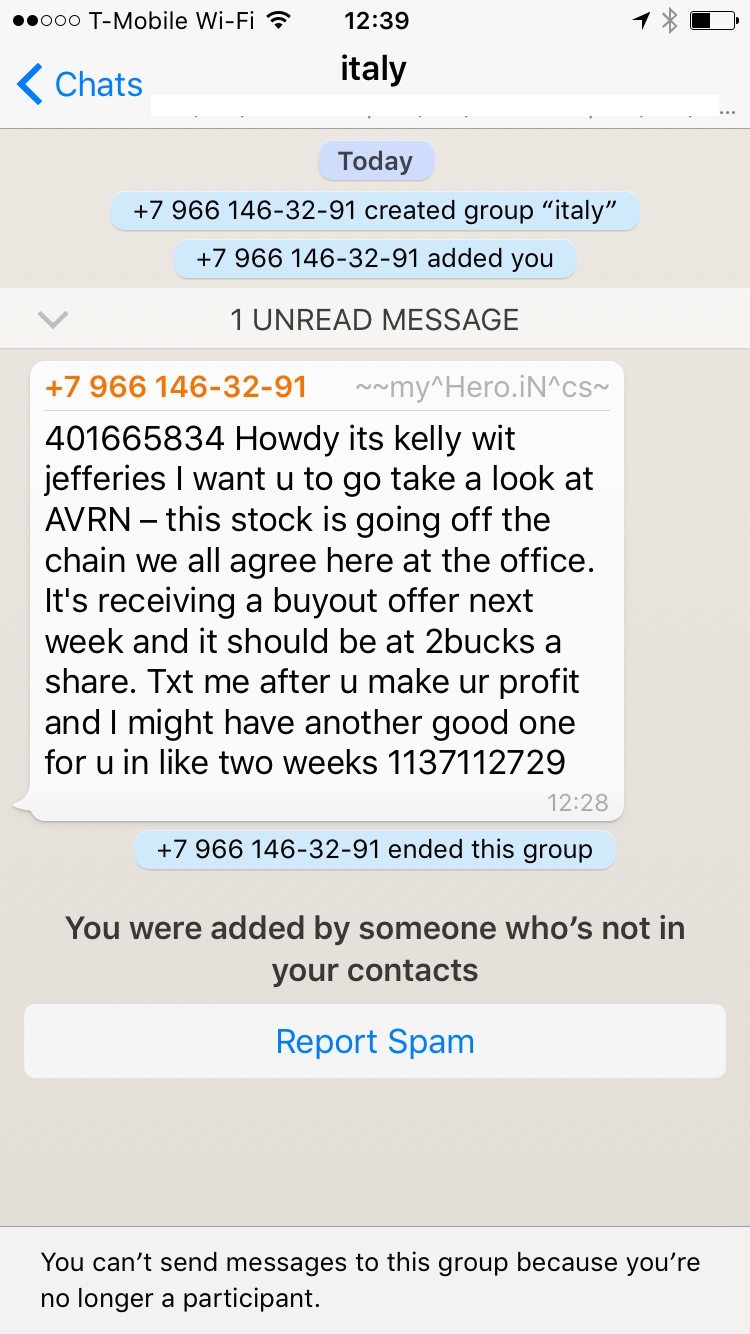

The WhatsApp Pump-and-Dump

Earlier today, I got this message through WhatsApp. I don’t use WhatsApp very much. I’ve received spam there before, but not much, and nothing that looked quite like this. A few moments later I saw this in my Twitter feed:

HOT TIP pic.twitter.com/VCJtyeLV9c

— Marisa Kabas (@MarisaKabas) August 21, 2015

Oh. Oooh!!

I searched around and found lots of complaints:

First instance of @WhatsApp spam? pic.twitter.com/lBhG2eDt4I

— Michael Wang (@michaelwang20) August 21, 2015

I just got… Spam on WhatsApp. Looked like an attempt to phish or scam somehow. “This is Jack from Morgan Stanley” Adding no Jack, bihhh

— Broke Boi Bill (@TheBeatnikBill) August 21, 2015

@WhatsApp Great, my first WhatsApp spam came in today. How did this guy get my number??? #nothappy pic.twitter.com/Av6qWjYH3X

— Alexander Teusch (@alexanderteusch) August 21, 2015

A number of people on Twitter complained that this was their first-ever WhatsApp spam; others noted that the spam was fairly obviously an attempt to pump and dump a low-cap stock in a new and novel way. So let’s see:

Here’s an article about the spike on this penny stock site, which notes the stock spiked after “a massive whatsapp text message went out this morning.” Not bad at all! WHAT A MOVE!!! Etc. The company description is excellent as well:

AVRA Inc (OTCBB:AVRN) is focused on solutions in the digital currency markets, particularly in offering payment solutions to businesses worldwide. The Company’s business model is divided into four distinct categories: AvraPay: to develop a complete, turn-key and painless way for merchants to accept Bitcoin as Payment; AvraATM: to promote usage and acceptance of digital currencies through the Company’s proposed network of ATMs; AvraTourism: to provide cryptocurrency payment processing solutions for merchants such as hotels and casinos; AvraNews: to provide a news portal focusing on digital currency news.

Yes. Correct. Bitcoin penny stocks.

By the time I got my spam, the stock had already tanked. But others had received the post earlier. WhatsApp groups seem to be limited to 100 users, so maybe my group was just a little too far down the list.

@_TC_ received something similar pic.twitter.com/oyiOh5eoSn

— Michael T. Halligan (@mhalligan) August 21, 2015

Did WhatsApp inadvertently help move hundreds of thousands of shares in a penny stock scam? Unclear. But that certainly seems to have been the intent. Pump-and-dumpers practice all kinds of creative manipulations and come up with new ones all the time. A few years ago, a scammer’s best bet might have been to issue a fake press release, hoping for coverage that might produce the desired effect — to “hack” the media, more or less.

But a savvy scammer today might see a similar opportunity in the platforms that offer access to potentially much, much larger audiences. WhatsApp passed 800 million users in April. A spammer has discovered a way to access at least some of those users, reaching them with messages that are fairly obviously spam but which, unlike spam emails, are not common enough that people have completely tuned them out.

Small cracks (security or design) in platforms of unprecedented size can present major opportunities for those looking to exploit them. Just ask any publisher 🙂

"There's Bears In The Pool!"

What is it that the kids these days say? “This could be us but you insist upon playing?” Well, precisely. Ladies and gentlemen, it is my pleasure to present you with what may very well be the summit of the bear video in its present form. Henceforth all bear videos will have to reckon with its mastery. Years from now, whatever shape the bear video takes will be both an acknowledgement of and reaction to its all-encompassing influence. Summer may be ending, but my God, what a way to go out. It’s rare when you can say that you were present at the creation but today you may.

And there’s even a happy ending. Enjoy. [Via]

Leon Vynehall, "Midnight On Rainbow Road"

It’s Friday. You did it. Whatever happens next, no one can take this away from you. You didn’t think you’d make it — there were times you considered giving up altogether — but somehow you put your head down and stuck it out and here you are. To celebrate, I got you this terrific song from Leon Vynehall. Enjoy. Savor the moment. Soon enough it will be Sunday night and then Monday morning and next week, and who knows how you’ll get through that one? Worry later. Right now let’s just celebrate this. I’m proud of you. [Via]

New York City, August 19, 2015

★★ Deep grays piled on whites in the morning sky, the clouds fluffy in the way of fluffy animals in an old children’s book. The air was much less hot than before but every bit as soggy, like the underside of a log. The midday sun hit hard on Union Square while it could, but by afternoon into evening, with the buildings intervening, the blowing air was a little clammy. Clouds flowed fast over the cornice lines of Fifth Avenue, east to west. What had been low gray clouds were suddenly burgundy after the sun was fully gone, and a bright yell0w-white crescent moon descended toward them.

Panda Bear, "No Mans Land"

Are you still pretending things are going to be okay? Good for you! Keep at it, pal. IF you can last another couple hours night will fall and then it’s time to call in the reinforcements. You can do it! Here’s some new Panda Bear, which may help. Enjoy.

Our Incorruptible Dead Girls

by Stassa Edwards

Maria Goretti haunts my television. Though the Catholic saint was murdered in 1902, long before television was invented, her presence is still felt. The eleven-year-old was stabbed fourteen times by twenty-year-old Alessandro Serenelli when she refused to submit to his advances. It wasn’t the first time that she had refused Serenelli, but this time, he came determined and armed with a knife. According to her voyeuristic hagiography, Goretti screamed and fought, “No! It is a sin! God does not want it!”

As she languished in a nearby hospital bed, Goretti forgave her murderer, clutched her crucifix, gazed at the Virgin Mary and died. Goretti had little — she was but one of many children in a poor Italian family — but, like a good Catholic girl, she had her virginity, and to have it stolen or lost would have been a mortal sin. It was perhaps the only valuable thing she possessed, so valuable that she took it to her grave. And it was in death — her body laid out before mourners — that Goretti found a kind of value that she never had during her short life. For her troubles, in 1950 she was canonized while her mother looked on, made the patron saint of rape victims.

Catholicism is filled with saintly women like her whose incorruptible bodies — especially virgins — insist on veneration, preserved in altars, patiently awaiting the Last Judgment. There’s Imelda, whose heart burst from the rapture of her first communion; Saint Rita of Casica, who endured a life of abuse at her husband’s hands; Agatha of Sicily who, after being forced into prostitution, had her breasts severed; and Saint Bernadette of Lourdes, who once told a fellow nun, “My job is to be ill.” The bodies of these dead women litter Europe. Their lives, like most saints, were marked with violence and tragedy. But, laid in altars or specially constructed chapels, their miraculous flesh welcomes the meditative gaze of pilgrims of have come seeking the guidance of the dead, even though dead women do not speak.

Pilgrims flock to dead girls, and they have done so for ages. In 1895, Parisians gathered at the morgue. On April 3rd, the body of an eighteen-month-old baby girl had been pulled from the Seine — the next day a three-year-old girl. “Are these two sisters?” asked Le Petit Journal. The crush to see the dead girls became so intense, so fervent, that the Journal later reported that the police had set up a special service to keep visitors lined up in an orderly fashion; the morgue required crowd control.

Before the nineteenth century, the unidentified dead were thrown in the dank basement of a prison, a “stinking pestilent place,” one observer wrote. In the basement of a prison, death had been too real — visitors, he continued, “were forced to breathe the poisoned air of this grotto and put their faces against a narrow opening.” But dead girls demand an audience. So when the Paris morgue was moved and rebuilt in the mid-nineteenth century, it was designed to make looking at bodies easy, almost pleasurable. Bodies were displayed behind large glass windows, lined up one by one, displayed like an object to be consumed. Parisians could visit the dead girls, worship seven days a week, anytime from sunrise to sundown.

Behind the glass windows the of Paris morgue, the dead girls were displayed like the incorruptible bodies of saints. Enshrined, objects that could identify them were hung next to their bodies; clothes and jewelry laid next to the bodies like relics. Prints from the era show a familiar scene: Long hair falling over breasts, violent wounds hidden, faces peaceful enough that they could be sleeping. And like the dead girls of procedural dramas, their bodies never fester — removed before the rot of death set in. At the Paris morgue, the romance of spectacle was preserved.

The little girls pulled from the Seine were never identified, but that was never the point of publicly displaying them: They were a site for introspection, a jumbled mesh of mourning and vain superiority. They were a reminder of the dangers of city life; only in a city could two children be thrown into a river undetected and anonymous.

Charles Dickens couldn’t resist a visit to the Paris morgue; haunted by the bodies, he returned time and time again. He described gazing at the bodies as “like looking at waxwork, without a catalogue, and not knowing what to make of it. But all these expressions concurred in possessing the one underlying expression of looking at something that could not return a look.” Dickens could never quite reconcile the dead girls he stared at with actual living women. His dead girls work only as a clunky metaphor for the artfulness of death. In Dickens’ hands, the individual is turned into an uncanny object — a curiosity, a Madame Tussauds creation. When Dickens wrote about the morgue, his pen wandered to other dead girls he had seen. He recalls a woman pulled from a river near his home: “So dreadfully forlorn, so dreadfully sad, so dreadfully mysterious, this spectacle of our dear sister here departed!”

The bodies displayed in the morgue had obviously suffered: They had been drowned, shot, beaten, or starved. Pilgrims flocked to worship, but they also came to search — to linger over the dead girl’s body, to take into account every detail of texture, size, and color in her body, to detect the cause of death. In Therese Raquin, Emile Zola wrote: “There are amateurs who make a detour in order not to miss one of these representations of death.” Staring at corpses as afternoon entertainment might seem grotesque, but the distance between the spectacle of the morgue and a Saturday evening marathon of Law and Order: Special Victims Unit is slimmer than most would admit; Dickens’ morgue is the predecessor to the procedural dramas’ dead girl. They are both spectacle, both artfully formed.

I think about Goretti and her suffering sisters every time I see her on television. Olivia Benson and Elliot Stabler hover above the body; Gil Grissom inspects every microscopic detail. They gaze at her body, faces twisted with concern or disgust, uttering lines about justice and violence. In the procedural drama gendered violence is a given: Women will be wounded; women will be killed. Death is inevitable because the production of the dead girl is its very purpose. Law and Order, CSI, and their many incarnations all have a kind of liturgy that repeats from week to week: The dead woman is never at fault, yet because she is a woman, her sacrifice was inevitable.

There is a visual continuity of dead girls in cinema: Laid out on slabs, hair draped around pale bodies that belie the likely violence of their fictional deaths, they are peaceful, serene and silent. Covered by a medical examiner’s makeshift shroud or dressed in borrowed clothes, neither their bodies nor their narratives are their own. They are bound by a kind of artfulness. The dead girl must look convincingly dead, yet death must conceal itself under the mask of beauty. So she’s pale — the lily whiteness of her skin evokes another kind of metaphor — while her closed eyes and pale blue lips convey the easy transition from living to dead. Though the procedural drama relies on the endlessly violent deaths of women, it asks that her corpse lie: to maintain its allure, not swell or bloat or bleed. The putrid smell of death has no place on the television screen, in part because the incorruptible body does not decompose.

Procedural dramas also offer a kind of alibi that simply gawking at a dead body at the morgue did not. To watch television is not simply to relish the spectacle of the dead girl, it’s to participate in the making of justice, to become a detective. In these shows, there’s a strange tension between the religious gaze and the scientific gaze. The religious longing for the dead girl, for the reunification of the body, is cloaked beneath scientific longing: Pieces of the body are magnified through lingering close ups, excuses made by a medical gaze enhanced by jargon. Yet we’re still granted unfettered access to look at thighs and shoulders; the metal carts, empty eyes, and blue lips are little more than cover granted by the objective medical work played out on screen.

If the stilted language and look of science cloaks longing, then the dead girl’s inability to speak is a fantasy in and of itself. The dead girl’s body is the only fundamental source of truth. It carries on it clues about her murder, so her entire body must be gleaned. Flakes, dirt from under her nails, microscopic evidence is all gathered placed into envelopes and jars. Labelled and preserved, these objects of veneration tell us something that victim is herself unable to mutter.

Alessandro Serenelli repented for his murder of Maria Goretti, and after serving three years in a local prison, Goretti visited him in a dream, giving him lilies, “which burned immediately in his hands.” He later became a lay brother in a Capuchin monastery and reportedly prayed to her every day, calling her “my little saint.” He joined Goretti’s mother at the girl’s canonization. That Goretti was dead seemed to be the very purpose of her existence. Her body became what no living girl ever could be: a miracle and a spectacle.