Friday in Cairo: The "Day of Rage"

by Christian Vachon

Gordon Reynolds — the pseudonym of a teacher in Cairo, dictated this over the phone to a friend not in Egypt. (For real-time dispatches on today’s demonstrations, follow him here.)

“Mister, Are you going to the protests tomorrow?” a student asked me on Thursday.

“No,” I said.

“It’s going to be worse than Thursday. Everything begins after Friday prayers, around twelve-thirty.”

“If I were going,” I said, “What part of town would I go to?”

“If you were going,” he said with a grin, “Then you should go to the mosque in Khan el-Khalili on Al-Azhar Street.”

***

The next morning at 11:45 a.m., I was in the back of a taxi, heading to the mosque on Al-Azhar for Friday prayers.

Standing on the side of the highway, facing the oncoming traffic was a policeman. Suddenly, our car accelerated, speeding towards him. The officer jumped to the road’s shoulder as my driver veered our speeding car at him. The driver looked up at me in the rearview mirror and smiled and laughed.

On #jan25, it was tweeted that Coptic Christians would attend Friday prayers to help protect Muslims, but as I stood in the back of the mosque, I saw no sign of them. In his sermon, the Imam spoke of how Mohammed came to bring light into the world, and through Islam, draw all men together into this light. He said that as Egypt goes through this time of trial, what is required most is patience — that change comes through restraint, not violence.

At 12:30 p.m., the mosque emptied into the narrow streets of Khan el-Khalili. On the way out I began talking to a store owner in his sixties. He invited me into his antique shop for tea.

“I don’t think there will be violence,” he said, as we sat outside his store. “What is accomplished if I break a policeman’s face? That man has a family. We are all the same people. In Islam we say, ‘To take a life is to take every life. To save a life is to save every life.’”

Then, a plump older gentleman wearing glasses and a sweater ran over to us. “The fighting has begun,” he said.

* * *

There were hundreds of young men and teenagers gathered on Al-Azhar Street when I arrived. They carried rocks in their hands. On the north end were Egyptian police in riot gear. The first set of roughly thirty officers were in position approximately one hundred yards on the north end of Al-Azhar Street. Two hundred yards behind them was a second line of police in position to keep the first from being surrounded from behind.

The objective of the protestors was to march down Al-Azhar Street to Tahrir Square where groups had amassed from other locations throughout Cairo.

The protestors chanted, “Bo-ttle, Bo-ttle, Bo-ttle.” With each syllable, they banged their rocks on the metal railing that separated the street from the sidewalk. As they chanted, the front protestors stared down at the line of officers linking riot shields and walked towards them.

Outnumbered, the police held their positions.

The first cannon-shot of tear gas sent the crowd running back. Then came the second and the third. The crowd retreated as police chased them up Al-Azhar Street. I was too close to the charging authorities to run back, so I turned into a side street. I had not gained more than a few feet before a teenager grabbed my shoulder and said, “No, they’ll follow you there, come.”

He jerked me into the entrance of a building where six of his friends had gathered. Other Egyptians tried to force their way inside, but the teenager reached up, pulled down an aluminum gate, and secured it with a padlock. Then he turned to me and extended his hand.

“I’m Nasr,” he said, “It’s okay. You’re safe here.”

We walked up eight flights of stairs and onto the roof where there was a group of six men — most in their early twenties, and six teenage boys and a small child, all looking over the edge down onto the street below.

* * *

There were three streets involved in Friday’s fight for Al-Azhar. At the ground level was Al-Azhar itself — the majority of the conflict between police and protestors took place here. Above this street was the first elevated highway, roughly four stories from ground level. Above this was a second elevated highway, roughly eight stories above ground level and nearly parallel to our position on the roof.

For the next six hours, protestors and authorities battled each other in effort to take advantage of the higher ground and gain control. When police charged forward on Al-Azhar Street, protestors ran up the first elevated highway and pelted them with rocks and bricks. In response, police units and tanks would charge the second elevated highway, firing rubber bullets and tear gas at the crowd until protestors retreated.

Trapped inside the building as the fighting endured without pause, I watched this back and forth battle for position and passage continue until after nightfall.

There have been rumors that this uprising is the work of the Muslim Brotherhood, but the majority of protestors I watched battling all day were teenagers — some of them just barely so. Some wore flip flops. Others charged at police barefoot. There were adults among them, but as the afternoon hours passed and I watched them continually get tear-gassed only to return with defiance, it seemed to me that I was watching enraged kids with nothing to lose.

* * *

On the roof, Nasr introduced me to Ahmed, a man in his forties who appeared to be in charge of things. “You’ll be safe with me,” he said when we shook hands. As he spoke all I could hear was the continued ring of tear gas cannons down below. Protestors had thrown some of the spewing gas canisters up on the second elevated highway across from us. The wind carried the gas towards the roof of our building.

My eyes watered as the fog blew over us. My throat burned. Ahmed led me to a faucet. We splashed water on our faces as we struggled to breath.

“I am so sorry that this happened to you in my country,” he said to me.

When the cloud had dissipated, one of the teenagers in the group decided to avenge our gassing. He picked up a brick and threw it down at the police below. Spotting this, an officer on the second level of the highway fired a canister of tear gas at us. It flew past my head and landed on the back corner of the roof.

We ran down the stairwell for cover.

Sitting on the concrete steps, with tissues over our mouths and noses, our eyes tearing as the continuous pop of gas cannons echoed on Al-Azhar, I felt a tap on my shoulder and turned.

“Your email address?” the teenager who threw the rock then asked. “For Facebook. We can be friends on Facebook.”

The rest of the group nodded. They too wanted to be my friends on Facebook.

* * *

By late afternoon, some of the rocks were now being aimed at us. Frustrated that onlookers were not joining them, some protestors targeted the spectators watching from the rooftops. We were forced to take refuge in the office of a men’s clothing manufacturer on the fourth floor of the building. Inside Ahmed turned the television to Al-Jazeera. They were broadcasting video of the fighting outside our office window.

At roughly 6 p.m., I looked down and saw that two trucks filled with back-up reserve officers had arrived. An additional one hundred reinforcements exited and formed two lines. For the next three minutes a rapid succession of cannon blasts rang from outside. In formation, the replenished officers pushed forward. Unable to see or breath, protestors abandoned their pursuit and authorities regained control of Al-Azhar.

The streets clear of fighting, I said goodbye to my friends and thanked them for keeping me safe. I took a white rag, tied it around my face, and walked into the smoky night. The air was still hazy with gas, forming halos in the streetlights. Chunks of concrete littered the pavement. There was a team of three officers standing at the intersection. They reached for their batons when they saw me approach. I lowered the mask and threw my hands up. They dropped their arms. “Taxi?” I yelled.

“Straight ahead,” they replied, and pointed me down Al-Azhar.

I started down the street and headed towards the highway. The roads were flooded with Egyptian families, traveling in packs, all trying to get home. I passed half a dozen burning tires. They sent black clouds of smoke into the purple sky. Then, reaching the highway, I stopped, stared at the oncoming cars, waved my arm, and waited.

These Things Happened

• Spoiler alert: This “Lives” column is composed entirely of the last lines of New York Times Magazines “Lives” columns from 2010

• Consider this: Here is a list of songs from David Bowie’s “Berlin trilogy” ranked in order of plausible thematic interpretation

• Road rules: You’ll want to follow this advice on how to behave at Jeff Mangum’s ATP set

• Watch and learn: Here are the things you figure out when you watch TV for money

• Learn and share: A visit to the Modern Language Association convention results in an intriguing proposal

• Learn and sing: It’s the best songs about New York without “New York” in the title

• Don’t look back: American race relations 137 years ago… and today

• Don’t look down: You have questions about heaven, right?

• Don’t look away: Here’s how they’re trying to take your rights away now

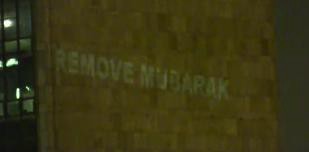

Photo by David Berkowitz, from Flickr.

Our Men In The Field

Even before the Wall Street Journal put a stopwatch on it earlier this year, fans knew it. There’s just no way to watch a football game, let alone follow the NFL’s shouty, certainty-intensive news cycle — if “news cycle” is the right term for something that reaches its analytical apex frequently during Herm Edwards’ livelier televised free associations — without noticing that the greater part of the NFL experience is about space and time and waiting and talking. That there are roughly 11 minutes of actual football in a given game is a neat tidbit, but not a surprise. The director cuts between things and Dan Dierdorf says “I’ll tell you what” and then tells you exactly what, and then there’s a commercial break and then it’s back at it. The sun goes down while all this happens, and manic little moments from other games interject and recede. And, at home or in the stands or in some wing-afflicted bar, we drink stuff and eat stuff and talk to other people. When the game is beautiful, it’s beautiful in little nervous interpolations to the general grunty lurch. Football doesn’t flow in the way basketball does, or lull like baseball does, but it works. It’s comfortable, and as such it does not take long to get comfortable — on an unspoken level — with the idea that those 11 minutes take three-plus hours, that those three hours take a week, and that three-or-so hours of actual football take five-or-so months. And then, all of a sudden, it stops.

Well, not yet. It’s not over yet. There is a NFL-related football game this week, but it’s the Pro Bowl. Scheduling the Pro Bowl — the NFL’s annual hungover half-contact all-star nonstravaganza — before the Super Bowl is almost cruel, given the contrast in engagement, interest and more or less everything else between the two. The spam infantry at Demand Media will be awake for the next eight days in a nonstop oegy of crummy Super Bowl-tie-in recipe-generation, but no one will be searching for Pro Bowl seven-layer dips. (Pro Bowl chili, on the other hand…)

The Pro Bowl has a bunch of problems, which could be said to begin and end with the no-one-giving-a-shit issue. But the goofy, groggy distinctively Hawaiian idyll of the Pro Bowl seems especially out of place when sandwiched between games that people actually care about, in a sports media environment in which even regular season games between Buffalo and any other team must be treated like a matter of global geostrategic import. To look at past box scores, it’s not out of the question to wonder if the Pro Bowl — which features those NFL players healthy, willing and competent enough to engage in a full-pads scrimmage in Hawaii — might actually be fun to watch, at least for lovers of long passing plays. But the competitive energy of the average Pro Bowl is somewhere between “Rock’n’Jock” and the Puppy Bowl, and while the friendliness of it all is appealing in the abstract — and doubly so when taken in contrast to the NFL’s otherwise unceilinged escalation of rhetorical brinksmanship and concussive intent — the game itself is slack and sloppy and almost impossible to watch. Without consequence or seriousness or competition — and without violence, to the greatest extent possible, due both to restrictive one-off rules and no one wanting to tear an ACL half-assing their Patron hangover through a go-route — the Pro Bowl barely feels like a football game. It’s football without football, and the comfort of what’s going on out there on the field is oddly discomfiting and enervating (and plain boring) to watch. A friendly game of football, even between the best football players on earth, barely feels like a football game. And that’s probably quite enough about the Pro Bowl.

But because no one who cares about football is talking about the Pro Bowl this week, and because there is no other football this week, and because all that NFL media space needed talking-in, something strange happened to the NFL discourse this week. Where next week there will be discussions of legacies and fan bases and individual match-ups and goofy bets between the mayors of Pittsburgh and Green Bay, there was this week a lot of staring into/being-stared-into the abyss of Fan Guilt. With the revelation that the injury that knocked Bears quarterback Jay Cutler out of last week’s game — and left the streets of Chicago strewn with nylon replica jersey ash and awash in bitter, “Chicken Cutler”-grade punnery — was a serious-sounding knee injury, it seems a reasonable enough time to do it. There’s also the matter of both the Steelers and Packers bringing multiple concussion victims with them to Dallas for the Super Bowl; Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers has suffered two this season, and was rumored to have been concealing another after Julius Peppers came startlingly close to fitting his entire 6–7, 283-pound body through Rodgers’ facemask on one gut-wrenching hit. Peppers was later fined $10,000 for the tackle, an amount that’s a little more than one one-hundreth of his weekly take-home salary. Which, in terms of carnage and fan response thereto and haphazard disciplinary ministrations, makes the week of the conference championships something like the average week in the NFL. The difference, this week, is that with the NFL media’s froth machines powered down for a week of maintenance and Rodgers et al nursing their non-concussions beneath ice packs in dim rooms, the dearth of other readily available topics and the manifest obviousness of the NFL’s brutality problem makes it tough not to talk about it even a little bit.

“Everyone is getting hurt, in awful, long-term ways, all the time,” Tom Scocca wrote at Slate earlier this week. “How will football adjust to this reality, as the news sinks in?” Ben McGrath addressed the same question in a long feature in this week’s New Yorker, a piece headlined “Does Football Have A Future?” These are important questions (and, to Scocca’s credit, questions he has been asking in various forms all season), but their elevation from constant ringing-in-the-ears background noise to the discursive forefront has more to do with the fact that they’re competing against #ProBowlSnubs and #SuperBowlDipRecipes for traction this week. There are football fans who really, truly do not care about this sort of thing — the ones sending nasty emails to Wisconsin health columnists who wonder about Rodgers’ contrecoup issues, accusing those columnists of being objectively anti-Packer, for instance. There are, I think, just as many who are not like that.

I’ve been asked, with increasing frequency as the season has gone on, if I actually like football, and I’ve wondered about it myself. The answer is yes, at least insofar as I enjoy watching the games, fussing over my fantasy teams, having a valid five-month excuse for afternoon beers, and coming up with new ways to compare football players to foodstuffs. What has left me half-exhausted and short-tempered and trying and not always succeeding to avoid peevish what-is-the-MATTER-with-you-people self-righteousness is not so much that people refuse to take football seriously enough — there is plenty of that, from the NFL’s brand managers on down to the dude trying to torch his Cutler jersey — but the fundamental unseriousness of all this seriousness. What has been discussed this week as the NFL’s doomsday scenario has already come to pass. Former NFL lineman and football historian/English professor Michael Oriard tells McGrath, in the New Yorker piece, that he wonders “What happens if football players become like boxers, from lower economic classes with racially marginalized groups.” He continues, “If it gets to the point where it’s rich white guys cheering on hits by black guys and a Samoan or two, Jesus, I hate to imagine we’re indifferent to that.” There’s no reason to have to imagine that, of course.

It’s difficult to imagine any fan or player — anyone outside the NFL’s front offices, honestly — who thinks that the current way of engaging the NFL’s inhumanity issues is satisfactory. The question of football violence and its costs — the older ex-players, shuffling and ghostly in their sudden senescence, the younger ones betrayed by damaged brains and fogged-in by a demi-epidemic of painkiller addiction — has become darker and more difficult as the season has worn on, with new reporting unfolding new and more insulting outrages. Fans know that the NFL will not deal with this question — here’s an article on an anti-concussion campaign from 1995; see if you can spot any progress. But boardroom cynicism is a fact of all of our lives, it’s simultaneously the subject and the object of our news, and an inescapable subtext in our entertainment. We learn to identify that and recalibrate, to reason and read around it in the direction of knowledge, without even knowing we’ve learned it.

If the NFL has an inhumanity problem, it’s not one that’s going to be solved by indiscriminate fines and haphazard bans and the lawyer-vetted semaphore that emerges, in a flurry of fragile forcefulness and willful opacity, from the commissioner’s office. And it won’t be solved, either, by removing football’s essential and fundamental violence from the game — that’s the Pro Bowl, and no one wants that. (It’s also something that no one is proposing, but which would seem to be the biggest threat and most likely outcome of the NFL’s current anti-headshot efforts if you listened to certain players and pundits) But there’s something heartening, just in the very fact that it happened, in this past week of talking about serious things. As the NFL continues to push further and further into the red, the new depth of public engagement with the NFL’s inhumanity issues suggests that fans have been watching these games more closely than the NFL’s ruling cynics might have guessed.

The greater part of every NFL broadcast, it seems like, is given over to commercials that insist, in a dozen different ways, that we define ourselves by what we consume. And so we get what marketing and advertising gives — new anxieties and ever-goofier fatuities of the “does this beer make me look gay?” variety. But the NFL issues the same message to those who consume it, and this season’s latticing of interlocking brutalities — scored, unconvincingly, by the increasingly baroque Football As America sentimentalities of the NFL’s branding people — have made the challenge in that more and more difficult to ignore. The fan quiescence that the NFL seeks is something as glib and brutish as a Fox News “Support Our Troops” chyron — the sort of support that requires nothing but arms-length sentimentality about Those Brave Boys on the television getting themselves harmed for us.

Liking football, or loving football, does not necessarily have to mean loving what it is now — it doesn’t have to mean tolerating a confederacy of oligarchs treating their (human) employees as a stubborn line item, it doesn’t have to mean ignoring the trauma those (human) players suffer and lining up or paying up or otherwise submitting to simply lap it up. Spend enough time as a football fan and its strange rhythms become comfortable, even comforting — those 11 rough minutes spread strangely, happily, narcotizingly across those Sunday afternoons. But we are living with and living in the national rot wrought by the bleak, selfish sentimentality that says our troops are out there solely to insure our continued comfort. The comfort of the NFL comes at a cost, too, and it is also complicated. The fans will not have a seat at the table when the players association and the owners sit down this spring to figure out what the next NFL collective bargaining agreement and future NFL seasons will look like. But our seat on the couch, or in the stands, matters as much or more to those with the real power in the NFL — the ones with the power to acknowledge and engage and mitigate the effects of the NFL’s inhumanity problem on the players who give (and gave) the game its present power and wealth. The relative strength in our numbers depends on how we use it, and the conditions that we set for continuing to occupy all these couches.

David Roth co-writes the Wall Street Journal’s Daily Fix, contributes to the sports blog Can’t Stop the Bleeding and has his own little website. And he tweets!

Image by Chad Davis, from Flickr.

New York City Police Commissioner Told Me He Likes Enya

by “David Shapiro”

i am drinking a fruity cocktail inside Cipriani, a gala hall on 42nd Street that’s about the size of a football field and decorated like a palace. mike is around here somewhere, interviewing the general manager of the New York Mets. tonight we are at an event that is hosted by the Police Athletic League to honor the organization of the New York Mets, who, as the security guard at work told me today, are one of the worst teams in professional baseball despite their enormous payroll. behind me, a heavyset man with a Queens accent and a haircut from Goodfellas walks through the entrance and admires the lavish setting and says “so this where they’re puttin’ all their money, huh?” and some other heavyset guys laugh. the haircuts here fall mostly into two categories: wispy white comb-overs for the Mets organization and junior bouffants and crew cuts for the Police people

in front of me, 1980s Mets icon Keith Hernandez is milling around by himself and sipping a cocktail. he’s the person who i want to talk to most tonight beside Jim Leyritz, another Mets icon who was charged with manslaughtering a woman while he was drunk driving but got off in 2009 because she happened to be drunker than he was and was not wearing a seatbelt. life is like that sometimes i guess. anyway, Keith Hernandez is very tall and looks exactly like he did when he starred in a Seinfeld episode like 15 years ago

so i go up to Keith Hernandez and say “hi my name is david and i write for a culture website — can i ask you one question please?” and Keith Hernandez nods and i ask “what is your favorite Seinfeld episode beside the one you’re in?” Keith Hernandez says “i don’t really watch it…” and i give him a bewildered look like “how could you not watch Seinfeld? you’re Keith Hernandez, one of the stars of Seinfeld!” and Keith Hernandez says “i just don’t watch primetime TV — it comes on right when i’m eating, you know?” Keith Hernandez is very warm and i nod even though i don’t think Seinfeld has been on in primetime for at least a decade

i ask him if he watches his own episode and he says “well, yeah, i watched it a couple times, but i can’t watch it that much because i get embarrassed. sometimes i’m channel surfing and it’s on…” and then i thank Keith Hernandez, who, as i’m disappointed to realize, doesn’t really like Seinfeld but doesn’t want to say it explicitly

then i walk back to the press area and drink another cocktail and wait for more guests to arrive. there is an elevated DJ booth in the corner of the room and right now the DJ is playing a spirited live version of Cheeseburger In Paradise by Jimmy Buffett and a few minutes ago he played a Frank Sinatra song whose name i don’t know. i think if the NYPD had music charts, Frank Sinatra would have completely dominated for the last 70 years

then mike comes over to the press area and the New York City Police Commissioner walks in and gets his picture taken by about 15 photographers. i notice he has a single raindrop on his shoulder, probably a drip from the ice melting on the scaffolding outside. it is almost poetic. mike leans over and whispers “what are you gonna ask him?” and i whisper “probably what his favorite cop movie is?” and mike goes “shit that’s a good one, can i steal it?” and i think about it and say “okay fine”. later he will tell me that the Police Commissioner’s favorite cop movie is Police Academy

then a man with a junior bouffant haircut goes up to the Police Commissioner before we can reach him and says “this is a real nice function, thanks for havin’ us here” and they shake hands. then another guy comes up to the Commissioner and introduces him to a man who looks like he’s about 3000 years old and whose hair is so wispy that he makes Gandalf look like Jimi Hendrix. zing! and so now the Police Commissioner is talking to this old dude about their rain footwear. the Commissioner is wearing black synthetic winter boots and the old dude is wearing tan leather Timberland boots. the Commissioner says “yeah, these get great traction and they’re very light” and he lifts the sole of his boot to about the height of his knee and the old dude inspects the boot and seems to approve

a rollicking rendition of Piano Man by Billy Joel plays over the PA

then mike interviews the Commissioner and then i do. the Commissioner is receptive to my questions and doesn’t look like he’s trying to get away from me which is a quality that doesn’t go unappreciated in any conversation. i ask him what artists he’s listening to right now and he tells me he has very eclectic tastes and that he really likes Foo Fighters, The Rolling Stones, and Rod Stewart. i ask him what the last song he listened to was and he tells me “something by Enya.” man i didn’t see that coming

then i wander around for a few minutes, surreptitiously following the cocktail waitress who is carrying the tray of pigs in a blanket and every few minutes i eat one. i know she thinks there is something wrong with me because guests are not supposed to follow the cocktail servers around gorging themselves on hors d’oeuvres, but we were told that we had to leave before dinnertime, so all the free food i’m gonna get out of this is gonna come in blankets

then John McEnroe walks in and gets his picture taken by the 15 photographers. he is hosting this gala and he looks really nervous. me and Mike watch him from a distance and try to generate questions as Is This Love by Bob Marley is playing over the loudspeaker and a generously proportioned woman takes a self-pic with John McEnroe. now he is talking to the owner of the Mets, Fred Wilpon, and he seems really weird because he shuffles his feet and speaks hurriedly and doesn’t make much eye contact. mike notices too and whispers “do you think he’s on something?” and i shrug

then a heavyset old man in big black sunglasses walks in and John McEnroe hurries over to him and says “take your glasses off, stay awhile!” and then introduces Fred Wilpon to the man in the black glasses by saying “say hello to my father, john mcenroe senior” and they all chat for a while and John McEnroe turns to his dad and says “be careful, it’s gettin’ slippery here” and kicks against the floor to communicate that it’s slippery

a few minutes later, a reporter will go up to John McEnroe to interview him and McEnroe will agree to it but then he’ll immediately excuse himself and say he’ll be right back. then he’ll do the same thing to me, and then he’ll do it again to another reporter. it’s really weird because generally if someone doesn’t want to do your interview, they just politely decline and that’s that. John McEnroe has the air of a man whose wife just told him she wanted a divorce 15 minutes before he had to leave to go host a gala and he hasn’t told anyone else yet

so anyway, Fred Wilpon walks away from John McEnroe and John McEnroe’s elderly father and gets stopped by an NBC television reporter and gets interviewed and i am standing right behind Fred Wilpon during the interview. if you are watching the local news on NBC tomorrow in New York, and you see Fred Wilpon getting interviewed and there’s a kid standing right behind him typing on his BlackBerry, i am that kid and this is what i am typing

Sent via BlackBerry from T-Mobile

“David “Shapiro” is 22 and lives in New York City and has a Tumblr.

The Dark Side of Oscar Bait

by Eric Freeman

This week, The King’s Speech — the story of King George VI’s attempt to overcome a crippling stammer in the years leading up to and during World War II — became the most Oscar-nominated film of the year. Given the film’s pedigree, this high mark should come as little surprise; The King’s Speech is a first-class example of the “Oscar bait” subgenre. All the traits are there: subject matter dealing with an affliction rarely depicted in cinema, at least not with seriousness; a setting with great historical significance, especially to an Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences obsessed with World War II; a lead performance that requires a transformation, in this case vocally for star Colin Firth; an unobtrusive style; and a heartwarming story with a clear emotional arc. It was deemed a surefire Oscar contender even before anyone had seen it — its almost entirely positive reviews validated, rather than created, its reputation.

The dark side of Oscar bait is that these sort of movies usually get significantly worse upon examination. Crash, which wasn’t even much-loved at the time, has since been accepted as a manipulative piece of trash with little to say about racism in modern America. The same can be said of A Beautiful Mind and its relatively simplistic treatment of paranoid schizophrenia. While Oscar bait is successful — as in, bait often does win Oscars — these accolades also suggest they deserve to be mentioned among the greatest films of their respective decades. But Oscar bait is typically quickly forgotten — rewatched The Hours lately? Flashed-back to last year’s painful Oscar bait season? — as it turns out it should be.

I don’t know if the same fate will befall The King’s Speech, but I can say that it has a leg up on its genre-fellows by getting its subject matter pretty much exactly right in all the most important ways. I should know, because I’ve been a stutterer (or stammerer — the terms are typically used to mean the same thing, except the latter is more British) since as far back as I can remember.

In fourth grade, one of the compulsory “elective” courses at my school was to learn the building blocks of drama by staging a short play with about 10 other classmates and our patient, presumably overqualified instructor. After showing only modest abilities during my audition, I earned a dual role as a tavern regular — yes, we were in fourth grade — and innkeeper in a severely abridged version of Rip Van Winkle. If memory serves, I had about ten lines of varying length, most of which involved telling the freshly awoken Rip what year it was, and that the one-time general George Washington was now running for president.

These were not difficult lines, but I nevertheless had intense difficult saying them during even the earliest rehearsals. This was perhaps the worst period for my speech in my life, most likely because I was old enough to have some sense of our emerging social hierarchy. When I couldn’t speak my assigned lines, I felt a deep sense of embarrassment, a feeling that was only compounded by my classmates’ attempts to finish the lines for me. At the time, it seemed like they were mocking me, although it now seems obvious that they just thought I’d forgotten my lines, and I yelled at them for it. Eventually, my shame and inability to handle the pressure of the play forced me to quit. I spent the rest of these elective sessions in isolation with our class teacher’s aide engaged in some other form of academic enrichment.

I tell this story not to elicit sympathy but to give some sense of the world of the chronic stutterer. The play was only about 40 minutes long and wouldn’t be seen by any more than 50 people who already knew me reasonably well, but, to me, it was the potential end of the world. When you stutter, each social interaction becomes an opportunity for embarrassment, a chance to show your social peers — or, even worse, strangers — that you are somehow incapable of expressing yourself as a “normal” person should be able. In a sense, you think that everyone will assume there’s something wrong with you. Since speech is often the basis of interaction for two people, there’s an attendant fear that people will simply think you are not worth respecting.

One of the greatest traits of The King’s Speech is that it understands this feeling extremely well. Prince Albert, or Bertie, the future King George VI, has to deal with issues far more important than putting on a play for a bunch of disinterested 10-year-olds, but he doesn’t only struggle with his speech in moments that would put pressure on any person. When he tells his daughters one of their favorite stories, he stammers. When he gives a fake radio address in front of his short-tempered father, he stammers. While each of these people is intimately familiar with his impediment, the fear is still there; despite their love for him, his daughters may not come to respect him, and his father may believe that his son is unfit for the title he was born into. For him there’s very little difference between a speech in front of a mass audience and an interaction with those who love him most. In each case, shame lurks closely by, ready to pounce. More than anything, this is why Colin Firth is about to win the Oscar for Best Actor — he absolutely nails the simultaneous fear, shame, exasperation and effort of those who have trouble saying what they already have perfectly formulated in their heads.

This is not to say that The King’s Speech gets every aspect of stammering correct. In his appointments with speech therapist Lionel Logue, played by the only moderately hammy Geoffrey Rush, Bertie engages in all sorts of ridiculous exercises like jiggling his limbs while chanting and doing breathing exercises with his wife sitting on his diaphragm. Speech therapy is far more often a dull exercise, and the film doesn’t really get this right until its final scenes, when Logue and Bertie repeat difficult lines in rapid succession to make troublesome sounds familiar. This is a Hollywood film, though, and perhaps some level of dramatic license is allowed for specifics that can only be identified by the most knowledgeable viewers.

The same cannot necessarily be said for historical inaccuracy, though, and it’s there that the film has received most of its criticism from middlebrow critics. (Some cinephiles, including the fine folks at Reverse Shot, claim that it has some of the most annoying uses of wide-angled lenses in recent memory, but they are mostly outliers.) Take Isaac Chotiner of The New Republic, who finds it disheartening that director Tom Hooper and screenwriter David Seidler would gloss over the Nazi sympathizing of Bertie’s brother David — aka Edward VIII, who abdicated the throne to marry the American divorcee Wallis Simpson, here presented as an annoying and loose woman — or Bertie’s own difficult working relationship with Winston Churchill. These are widely accepted historical facts, things that attentive filmmakers should presumably get right if they’re attempting to produce something approximating a historical document.

However, to criticize The King’s Speech on historical grounds seems like a misjudgment of the concerns of the film. This is not to say that these inaccuracies should just be shrugged off — in an ideal movie, they’d be correct — but saying this film isn’t very good because it doesn’t understand World War II geopolitics is like saying that Black Swan doesn’t accurately depict the life of a ballerina. These issues can be indicative of greater problems, no doubt. Yet, like the Harvard inaccuracies of The Social Network, they don’t explain why a movie is good or bad.

At the same time, personal experience with the subject matter of a work of art cannot serve as a referendum on the quality of the piece — it is a way into criticism rather than its end result. In this same vein, the fact that I find the depiction of stuttering in The King’s Speech realistic is relatively unimportant. Because while Bertie is easy to empathize with, the film itself wouldn’t be worth a damn if it didn’t reflect the realities of life in general. Otherwise, only we happy few who stutter would find anything to like. Who else actually knows anything about what it’s like to stutter regularly?

The most admirable trait of The King’s Speech is that it understands stuttering as an extension of the difficulties of daily existence. To be fair, it gets at this point by also understanding the specifics of the speech impediment. When Bertie gives his climactic speech in support of England during wartime, he has not suddenly overcome his stammer — he speaks with difficulty on several difficult sounds. Importantly, though, he gets through them by learning to deal with the problem, not by eradicating it, which happens to mimic my own experience in becoming more comfortable speaking in potentially embarrassing social situations. To its credit, this is a film of small victories, one in which gradual success is the reality instead of extreme victories. Bertie succeeds not by turning into a different person, but by becoming the best version of himself he can be.

That sort of dogged attempt to become a more capable and comfortable person is part of all lived experience. Bertie’s ability to speak in public is not so different from his brother’s struggles with his sense of duty and his desire to be with the person he loves; nor is it much different than the Queen Mother’s need to support her husband even when it seems like he may never be comfortable with the sound of his own voice. Each person has their own version of this journey: my increasing willingness to go on the radio or speak at public events is not terribly different than a friend’s attempt to maintain a valuable friendship with a longtime-girlfriend-turned-ex.

The aftermath of Bertie’s climactic speech is one of contentment, not eternal triumph. He is greeted by sincere but not raucous applause from advisors and family members, almost all of whom know him well. Likewise, when Hooper cuts to listeners during the speech itself, he does so merely to show that it’s going over well, not that everyone is suddenly agog over the king’s oratorical greatness. It is one successful speech — and not even a particularly important one, given the monarchy’s figurehead status — in what will be a career of many. Bertie will go on to employ Logue’s services for years not just because they’re friends, but because he needs his help. The king will never completely overcome his stammer because no such outcome can exist. He can only improve his speech through practice and remain determined to present himself as best he can.

Eric Freeman is a writer and editor from San Francisco. He is a regular at FreeDarko and one of the authors of the site’s Undisputed Guide to Pro Basketball History. You can also read his basketball writing at Yahoo!’s Ball Don’t Lie and cultural thoughts at Plasma Pool.

We Desire That You Subscribe to Jauntsetter

If you subscribe to Jauntsetter this week — it’s the once-a-week email about local and fun travel! — you could win, of all things, a heart-shaped 2-quart LeCreuset casserole dish, and there is nothing I want more, so win it and give it to me.

The Role of Labor Movements in Egypt

The Role of Labor Movements in Egypt

Some things about Egypt that you may not have read about until now: “From 2004 to 2008 alone, about 1.7 million workers have engaged in 1,900 strikes and other forms of protest, demanding everything from wage increases to job security in state-owned industries that were privatized.” (That is not a thing that newspapers have room for in general, so we would not have heard much until now.) Here is a history of the labor movement in Egypt, from a socialist perspective; and here is an interesting history of “the co-option of the trade union structure” that began in the early 80s. As a sideline, here is a report from 2001 on the conditions of the more than one-million children aged seven through twelve who work in the cotton fields. Labor movements live and die in regime changes: for instance, Iran’s vigorous labor movement that was destroyed in 1953; similarly, labor movements can be strangled when support to them is denied by allies and neighbors, as in the Tunisian labor movement of the mid-1920s. Something people can do in London tomorrow: go demonstrate outside the embassy.

Helpful Hints For Arguing On The Web

How to derail a conversation on the Internet: “Excuse me, but I can’t believe you’re not talking about rape in the DRC. Why on earth aren’t you talking about that in a blogpost entitled ‘Kittens and Bunnies’?”

Republicans Are Strict Constructionists About Rape

Remember when everyone made fun of Whoopi Goldberg for trying to distinguish “rape” from “rape-rape”? Well now House Republicans want to get in on the action.

Our Critics Will Not Be With Us Forever

by James McAuley

“The age of evaluation, of the Olympian critic as cultural arbiter, is over,” wrote Stephen Burn recently in the New York Times Book Review. The sun may be setting on the “Olympian” stature the critic formerly enjoyed, while the age of everyman-as-critic is on the rise. Academic critics may not be in such danger — God did, after all, create tenure. So what of the future of the journalist-critic, the op-ed columnist and the professional cultural commentator?

There’s an assumption that most influential opinion and culture critics and commentators have been safely ensconced in the mastheads of prestigious publications forever and have used their fancy office letterheads to cultivate the kinds of reputations that can make or break an up-and-comer’s career — and that they have all been with us for what seems like forever, with plans to hold down their chairs far into the future.

Looking at the life-span of our current critics, however, reveals that our current crop has not, despite appearances, been with us as long as it may feel. What’s more, a review of the record suggests that a career in criticism can be, as one would expect, quite the gamble.

If the label “critic” can be applied in a general sense to those who whose commentary has shaped public discourse, there have certainly been some long-haul careers out there. Most successful opinion columnists, for instance, do seem to be around forever.

Walter Winchell — whose gossip column was distributed to more than 50 million people every day for over 30 years — worked at The New York Daily Mirror from 1929 until the paper closed in 1963. Later, Pulitzer-prize winning New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis wrote for the Times’ opinion page from 1969 until 2001. William Safire’s column, which also won a Pulitzer, you will remember, appeared in the Times from 1973 to 2005.

And Art Buchwald’s long-running humor column, at one point syndicated in more than 550 publications, was based in the Washington Post from the 1960s until just before his death in 2007. Mike Barnicle’s column appeared in the Boston Globe for 24 years, beginning in 1974 and ending in 1998, when he moved on to the New York Daily News and then the Boston Herald.

On the current Times opinion page, most of the columnists seem to have grown deep roots. At that paper, Gail Collins started on the editorial board in 19995, then was an op-ed columnist, then ran the page, and, since 2007, has been a columnist again.

Bob Herbert has been on the page since 1993. Frank Rich moved off the theater beat in which he made such an impact and began in 1994; Maureen Dowd in 1995; Paul Krugman in 1999, and Nicholas Kristof joined the paper in 1984 and, after serving as associate managing editor, migrated to the op-ed page in 2001. Of the others, David Brooks arrived in 2003, Charles Blow in 2008, and Roger Cohen and Ross Douthat in 2009 (although Cohen had been — and remains — a columnist for the Herald Tribune). Who knows? Maybe another Lewis or Safire is in the works. (Trish Hall, the new Op-Ed Editor for the paper, is a similarly a Times journeyperson; she has also been with the paper since 1986, with a brief intermission.) So if you feel like you have been reading most of these people for the last decade or two, you would be correct.

In the larger realm of cultural commentary, careers historically have tended to be long — so long as the critic’s opinions are in sync with the larger cultural sensibilities of the times. (Look out, Frank Rich!)

It turns out there may be some works of art that a critic just can’t afford to be wrong about.

A good example of a turning point that started and ended several long careers in film criticism, for instance, was the appearance of Bonnie and Clyde in 1967. Bosley Crowther, film critic for the New York Times since 1940, had enjoyed a long career of chiding overly patriotic movies. At the end of 1967, the year in which he wrote his scathing review of Bonnie and Clyde, he was shown the door. Sample: “This blending of farce with brutal killings is as pointless as it is lacking in taste.” (Or perhaps it was his review of Valley of the Dolls? “Shot in New York, New England and in and around Hollywood, the scenery is authentic in color. All else is false and fake.”)

Bonnie and Clyde, as it happens, was the same film that established Pauline Kael’s credibility at the New Yorker, where she remained, with brief intermissions, until 1991. You could even say that it was her famous first piece for the magazine — a 7,000-word defense of Bonnie and Clyde — that helped her to become perhaps the most revered movie critic of the twentieth century. Kael’s career didn’t start with the New Yorker; she’d already written for The New Republic, The Atlantic, and Partisan Review before she started. But it was her alignment and engagement with the values and ideologies of her times that afforded her the influence she later came to enjoy.

Janet Maslin had been a Times film critic since 1977 but, in 1999, at the age of 50, left the beat, shortly after praising Eyes Wide Shut. (This was right after Frank Rich left his post in theater, and restaurant critic Ruth Reichl left the paper and when Anna Quindlen quit the op-ed page — a time of that seems from this vantage point like a momentous upheaval, the likes of which is rarely seen.) She’s now still in the Times’ book department, along with Michiko Kakutani — who Norman Mailer famously called a “one-woman kamikaze” and who Jonathan Franzen called “the stupidest person in New York City” (impossible, of course) — who’s been with the paper since 1979 and has been reviewing books for thirty years.

More frequently, cultural commentators find themselves subject to the values of whichever editorial regime under which they happen to find themselves. The most famous obvious purge in recent history probably occurred during Tina Brown’s stint as editor of the New Yorker, during which she did away with a wave of folks who’d been with the magazine for decades. (Get ready, Newsweek!) Most audaciously, in 1997 she pushed out George Steiner, the celebrated book critic and public intellectual who’d written reviews for three decades. Also shoved aside: Terence Rafferty, Pauline Kael’s chosen heir; Wilfrid Sheed; music critic Paul Griffiths; theatre critic Mimi Kramer; and TV critic James Wolcott (whom she herself had brought in).

The post of the film critic, it turns out, is a particularly tough gig to keep or to enjoy if you are not so disposed — especially at the Times. When Bosley Crowther was let go, the paper hired Renata Adler as his replacement. She did only about 18 months before going back to the New Yorker. (She quite enjoyed Chitty Chitty Bang Bang!) One of Maslin’s replacements — hired along with Scott in 1999 — was Elvis Mitchell from the Fort-Worth Star Telegram, whose reviews, or perhaps conduct, were a bit too free-floating for the paper; they parted ways in 2004.

And now? The New Yorker film critics Anthony Lane and David Denby began in 1993 and 1998 respectively. A.O. Scott, Manohla Dargis, and Stephen Holden are now the Times’ film critics, and have been on staff since 1999, 2004, and 1988, respectively. (The hiring of Dargis was the last big outside critical hire in major New York publications in memory; the promotions of critics like Sam Sifton and Dwight Garner have all been evolutions of Times careers.) Alessandra Stanley, the paper’s television critic, took on that role just back in 2003.

Among the art critics, change has not been so fast. Holland Cotter has been in his post since 1998; the formerly fearsome and now slightly less-scary Roberta Smith began at the paper in 1986. Grace Glueck has been roaming that department for decades. There was, however, actually movement when Ken Johnson went off to the Globe in 2006.

So while it may feel that most of our critics have been around forever, installed on the various soapboxes of the New York media world, most of their reigns have been long but not actually anywhere near endless.

There is a way in which the origins of the perception of the critic as permanent, elevated and all-powerful come from writers, not readers.

When novelists like Alice Hoffman and Alain de Botton go so far as to, say, tweet the phone number and email address of a reviewer who has mildly criticized her book, or to post a nasty blurb on the reviewer’s personal blog, the critic ends up seeming all that more influential, a person whose opinion is important enough to warrant public outrage and attack.

In the age of Amazon and reader reviews, that kind of outrage may actually be the secret ingredient to the stature of the critic. How many readers today really care about what a big-league critic thinks about Freedom? Few — unless the critic’s work inspires a big stink? Sir Walter Scott may have warned writers not fear the critic’s brow, but, in this time of notoriety and opinion echo chamber, that fear may be all that makes critics influential.

James McAuley is a student in Cambridge, Mass.