Soon There Will Be Only One Kind Of Animal Left: A Mixture Of All Of Them

“The melting Arctic ice has brought polar bears and grizzly bears together and their hybrid offspring, known as ‘pizzlies,’ have been detected on Canadian islands. It is a trend that is happening with other species as well, and scientists are worried because it poses a risk to biodiversity.”

Cyber Hackers Will Return Us To The Flower Power Era

Space. It’s the final frontier. It’s that big black thing up above the clouds. It’s where we keep all the stuff that makes our mobile phones and computers and GPS systems work. It is also the next place that bad people will try to do bad things in. What does it all mean?

Our overwhelming reliance on space technology makes us acutely vulnerable were it to ever break down or be deliberately sabotaged. For those gathered at the conference on national security and space at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI) yesterday it was an issue they felt needed to be confronted more openly.

“It is a real issue and a real vulnerability,” explained Mark Roberts, a former space and cyber expert at the Ministry of Defence who has recently moved to the private sector. “What we are doing is making ourselves more vulnerable to attack than we had been formerly. My personal view is that a day without space is not going — as some people say — to send us back to the dark ages. It’s more likely to put us back into the 1960s.”

The 60s, eh? Bring it on! I am gonna burn my bra, go on a groovy acid trip, listen to some hippies bang drums, and then spend the next 50 years endlessly nattering on about how I was part of the most important generation in the world while generally fucking things up for everyone younger than me so that I can continue my journey of self-discovery with a bunch of BMWs and Viking Range stoves in a series of houses that continue to gain in monetary value even though those prices are completely unsustainable and stuff. Screw modern technology, this all sounds pretty good! Let’s kick things off the only way you are now allowed to introduce anything about The 60s.

Far out, man! If you need me I will be tie-dyeing a shirt and engaging in an orgy of self-celebration. Who’s with me?

Photo by Jimmi, via Shutterstock

Tommy Lee Is 50

Thomas Lee Bass turns 50 today in what is a pretty clear testament to the fact that good genes will usually triumph over a series of consistent attempts at self-destruction. If the anecdotes in the Motley Crue tell-all The Dirt are true, Tommy Lee once fucked a breakfast burrito, which, if nothing else, shows a level of commitment to the form that considerably outshines the efforts of other foodies. Happy Birthday, Tommy.

America's Worst Film Critic Shows His Face

Lois Lowry gets grilled by the wonderful Anna Holmes and Lizzie Skurnick at the 92Y uptown, Crystal Castles play with HEALTH at Roseland, Heart “rocks” the Beacon Theater, and America’s most overtly terrible film critic, David Denby, reads from his new collection at the Barnes and Noble uptown. OR you can watch the debates at Galapagos, if you can’t face it alone.

How To Make 17th-Century Delights: Curd Cakes

by Gina Patnaik and Lili Loofbourow

A series about recipes that may seem odd or outmoded and yet we’re curious to try!

As 17th-century delights go, curd cakes sounded good. Kinda like comfort food. When the two of us first came across the recipe, we placed bets on where curd cakes might fall on the Elegance-Meter. Were they dukes or peasants? Might (Dame) Maggie Smith have said, “What is a curd cake?” on “Downton Abbey” (back when it was good), or would she have readily ordered them up for tea? On the whole, curd cakes seem less festive than our previous concoction, whipp’d syllabub, what with the latter’s spume and special drinking vessels that draw up the froth-infused wine from below. Curd cake felt simpler. Humbler.

WERE WE RIGHT?

So, one of us (Gina) is trained as a chef. The other one (Lili) can’t cook, but loves 16th- and 17th-century recipe books. Together, we experiment. Trouble is, because we’re both grad students (she’s a modernist, I’m an early modernist), we tend to have very different ideas of what sort of experiment we’re conducting. For Gina, time in the kitchen leads to investigating alternative recipes and figuring out how these foods came together and evolved over time. Lili’s in it for the language (Candyed Eringo-Roots, Neats-Foot Pye) and the good eating. And so, while curd cakes are the ancestors of author Kate Christensen’s delicious nostalgia fritters, featured here the other week, our cooking efforts usually involve a couple of different goals.

Gina: “Our mission: to track down the true history of the curd cake.”

Lili: “Or just to find out what other things curd cakes were called? (And may I have more, please?)”

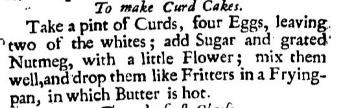

As with our whipp’d syllabub, our starting point was the 1696 edition of J.S.’s The accomplished ladies rich closet of rarities, which offers the following recipe:

In modern proportions, we estimated that might look like this:

• ¼ cup flour

• 2 tbsp sugar (or to taste)

• 1 pint of cheese curds (we substituted Cowgirl Creamery Fromage Blanc, but you could probably also use strained cottage cheese)

• 4 eggs (2 whole eggs + yolks from 2 others)

• Nutmeg to taste

Use a fork to mix the cheese curds with the flour, the eggs, sugar, and the nutmeg. Spoon them onto a buttered griddle.

We tried three different thicknesses, spreading the batter in the griddle to achieve different consistencies. We classified the resulting cakes as thick, medium, and thin — with thin meaning really quite thin. Here’s thick:

Here’s medium:

The thick and medium tasted a tad gummy; we vote for the slightly crisp texture of the thinnest cake:

And serve!

Curd cakes, it turns out, taste like surprisingly cheesy pancakes. After stuffing our faces, we got back to the question of whether curd cakes were classy. Delicious, yes. But high society? Maybe not? We speculated that curd cakes were downstairs fare, maybe the sort of dessert that Bates and Anna would have cooed over as they fell in love.

But we weren’t sure. We hunted around and found a 1597 Puritan cookbook called The Good Huswifes Handmaide for the Kitchin that offers the following recipe for “Curde Frittors”:

Take the yolks of ten Egs, and breake them in a pan, and put to them one handfull Curds and one handful of fine flower, and straine them all together, and make batter, and if it be not thicke enough, put more Curdes in it, and salt to it. Then set it on the fire in a frying panne, with such stuffe as ye will fry them with, and when it is hot, with a ladle take part of your batter, and put of it into your panne, and let it run as smal as you can, and stir then with a sticke and turne them with a scummer, and when they be faire and yellow fryed, take them out, and cast Sugar upon them, and serve them foorth.

(The Good Huswife also features “A Tarte to prouoke courage either in man or Woman,” but that’s a story for another day.)

Anyway, curd fritters seemed close enough to curd cakes and it all seemed nice and low-key, but then we also stumbled across this recipe from a book by Elizabeth Grey, Countess of Kent, which offers the following recipe for curd cakes:

“Take a pint of Curds, four Eggs, take out two of the whites, put in some Sugar, a little Nutmeg, and a little flour, stir them well together, and drop them in, and fry them with a little Butter.”

“COPYCAT,” we can say of the Countess, and did.

That cookbook, incidentally, is called “A choice manual of rare and select secrets in physic and chirurgery” and the title continues in this vein for some time before concluding with “as also most exquisite ways of preserving, conserving, candying, &c.;” It was published after the Countess’ death in 1653, and doesn’t it just drip with snobby self-praise? Exquisite! Choice! Select! Rare! And yet the Countess’ recipe is materially identical to the Puritan’s, proving once and for all that aristocracy is a sham and that curd cakes, like the Crawleys, transcend class distinctions.

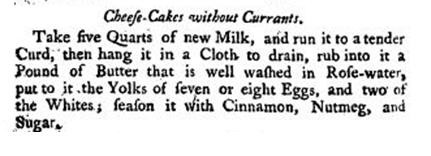

In 1755, just as George the future Mad King was about to turn seventeen (never suspecting the coming revolution), Sarah Jackson published her “The director: or, young women’s best companion,” which sets out the following recipe for Curd Cheese-Cakes:

Coming across this, we exchanged rich looks. Hidden within our simple curd cake were — or so we began to hope — the deliquescent delights of cheesecake! The Ultimate Democratizer. The kinship may be obvious to those reading this account, but we never suspected our interest in curd would take this curious and congenial turn. Cheese. Curd. Cake!

Our researches brought us across one other interesting historic tidbit: The existence, from the 17th century till the middle of the 19th, of a Cheesecake House. It had its start as one of the earlier buildings open to the public in Hyde Park. Variously known as ‘Grave Maurice’s head,’ Price’s Lodge, the Moated House, or just ‘The Lodge,’ it eventually became known as ‘the Cheesecake House’ because of the good cheesecake served there. By Queen Anne’s time it was more generally called ‘the Cake House’ or ‘Mince-pie House,’ “and according to the fashion which still continued to prevail, the beaux and belles used to go there to refresh themselves” with — and here was a happy thing — syllabub and cheesecake. They did in fact go together. Just like Sybil Crawley and her Irish chauffeur.

Previously in 17th-Century Delights: Whipp’d Syllabub

Gina Patnaik is a onetime chef and current Ph.D. candidate in English at UC-Berkeley. Lili Loofbourow is a writer in Oakland. She writes at Dear Television and over here.

New York City, October 1, 2012

★★★★★ Irresistible in the middle, very slightly demanding at the ends: the fall’s stock pattern inverting summer’s. The balance of brightness and chill made it seem reasonable to go crisscrossing Grand Street in search of a bakery with Hong Kong milk tea. No one had a pot ready. The appetite considered a small standard cup of New York cart coffee, but nor was a breakfast cart at hand. The reverie moved on to cafe con leche, in a nice thick rounded cup — but there was the office, and the office machine would do. Up on the roof, a light wind blew from east to west and sun shone white on the still-green trees across the street. It was too lively for basking in; the thing to do was pace around in it for a while. As the evening chill settled in, people had made their accommodations. A Yankees fan on the train had a Yankees knit hat, pompom-topped, and her companion wore long sleeves layered under his pinstripes. A pair of red cowboy boots walked by on the platform.

25 Days To Read "Cloud Atlas" Before Tom Hanks Ruins It Forever

I love David Mitchell and I love the essay he had in the Times magazine this past weekend about the experience of having his novel, Cloud Atlas, made into a movie. He writes about the way seeing a movie of a book changes the way we see the imagery of the book. And it made me very, very glad for my decision to have read Cloud Atlas this past month, before I see the movie that The Matrix-makers Andy and Lana Wachowski (and Tom Tykwer!) created out of it.

“Perhaps where text slides toward ambiguity,” Mitchell writes, “film inclines to specificity. A novel contains as many versions of itself as it has readers, whereas a film’s final cut vaporizes every other way it might have been made. Funny thing is, not even the author is immune to this colonization by the moving image. When I try to recall how I imagined my vanity-publisher character, Timothy Cavendish, before the movie, all I see now is Jim Broadbent’s face smiling back, devilishly. Which, as it happens, is fine by me.”

I’m glad that he’s happy with the way it came out. From what little I’ve read about him personally, he seems like a charming, down-to-earth guy. Everybody raved about the book when it was published six years ago, including two friends of mine whose taste in books I appreciate, and my wife, whose taste in books I also appreciate, and who knows my taste in books as well as anybody. But my wife (who reads five times as fast as I do, and so basically screens everything that comes out before I get to it) recommended that I not read it. She guessed that I would not like the way it jumps around in time and voice, taking on the styles of various literary genres (Azimovian sci-fi, Patrick O’Brien-style historical fiction, Elmore Leonard crime stories) or its overall theme, which is slightly spiritual and fantastical. She used words like “experimental” and “conceptual,” which are often red flags for me. (Because I’m such a close-minded, conservative jerk of a book reader, I guess.) So I gave it a miss, and felt okay about feeling left out whenever she and my other two huge-Cloud-Atlas-fan friends would get together and gush about it.

Then, a couple years later, she read another David Mitchell book, Black Swan Green, and immediately upon finishing the last page, said, “You have to read this. You will love it.”

I was almost finished with the book I was reading (Cormac McCarthy’s No Country For Old Men, which I thought was totally excellent — and in fact, since we’re on the subject of the nexus of books and movies, read more like a movie to me than any other book I’ve ever read. Probably relatedly, the movie the Coen Brothers made out of it is the most faithful film adaptation of a book I’ve ever seen.) So I picked up Black Swan Green and read it over the next couple of days. (It’s short and reads quickly.) And, yes, sure enough, loved it very much. Part of that love spurred from the fact that I am about the same age as David Mitchell, and so was about the same age as the main character in Black Swan Green, who was “coming of age” in the book, set in 1983. The book is apparently semi-autobiographical, and so that means that David Mitchell grew up in a place similar to where I grew up, the suburbs, at the same time I was growing up there, and thought about things in much the same way that I thought about things. (Probably in much the same way that lots of 13-year-old suburban boys think about things.) Because reading that book was one of those times that made me feel like someone had been spying on my memory without my ever knowing it, and then transcribed the thoughts with uncanny accuracy. This happens with the best books, right? The “Oh, man, that’s exactly the way I feel! Why didn’t I write that?” thing. It happens more with books than movies, I think, something that has to do with a novel containing as many versions of itself as it has readers, as Mitchell said. The slide toward ambiguity makes it easier for us to graft our specific experience of the world atop the writer’s version. (Or vice versa.) But it can happen with movies. Watching Donnie Darko for the first time was like that for me, too.

Anyway, I loved Black Swan Green so much, and was so impressed with my wife’s prognosticative ability, that I figured she must be right in predicting that I would not like Cloud Atlas. So I still didn’t read it.

A few years after that, Mitchell published his next book, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet, and my wife read it and was absolutely doing back flips about it. I think she might say this is her favorite book written this century or something like that. I would imagine it’s on her Top 10 list, all time. The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet is a love story set at a Dutch East India Trading post in late-18th-century Japan. This sounds about as far from any book I would ever pick up as any description of any book I’ve ever heard described. But, man, did she love it! She started talking about how David Mitchell might be her very favorite author and all that. So, since, I loved Black Swan Green so much, and since my wife, whose taste I appreciate so much, apparently loves everything David Mitchell writes, and I’d always heard all these other people talk about how Cloud Atlas was such a masterpiece and all, I got to thinking maybe I should take a crack at it.

But I never did. There are always too many other books to read.

A couple months ago, I learned about the movie that they were making about it. And besides thinking, how will they make a movie out of this experimental, conceptual book that I know weaves several different stories across several different centuries?, I also thought that I better read it right then. Because if I saw the movie, I would certainly never read it after that. I don’t think I’ve read a book after having seen a movie version of the story. It seems sort of like an impossible thing. Both for reasons of needing the suspense of not knowing the plot to pull me along, and also because of what Mitchell talked about in his essay: I like to imagine a book’s scenes in my head, the way the words make me imagine them, not how someone else interprets them.

I just had a conversation with a couple of kids about this last weekend. They’re eleven and thirteen, and I’m friends with their dad Mark, and I asked them what their favorite books and movies were, and they both mentioned The Outsiders, both S.E. Hinton’s book, and the movie that Francis Ford Coppola made out of it with Ralph Macchio and Matt Dillon. That book was a favorite of mine when I was a kid, too. Seeing the movie of it was one of the great moments of cultural betrayal of my young life. In the book, the character Dallas, or “Dally,” was described as having “small, sharp animal teeth,” and hair “so blonde it was almost white” and eyes that were “blue, blazing ice, cold with a hatred of the world.” I imagined him as nearly albino. And thin and lanky and wounded-looking. And this look, his shocking, sort of ghostly appearance, with its hints of inbreeding, became a big part of my understanding of his character. His psychic wounds came in part from looking so different from everyone else, so unhealthy, this was part of his outsiderness. But then in the movie, they cast Matt Dillon as Dally. Brown-haired, brown-eyed, super-handsome Matt Dillon! And they didn’t even bleach his hair blonde! If kids had said “WTF?!” back in 1983, I definitely would have said that. (I wonder if David Mitchell would have, too. I bet he would’ve.) I was furious. This didn’t make any sense, and it really robbed something from me that I’d found in the book. I explained this to Mark’s kids, and they agreed, but they were not as upset by it as I was, and, apparently, sort of still am. They’re pretty well-balanced-seeming, Mark’s kids. I think they might have even seen the movie before reading the book, somehow. I don’t know how. But they were like, “Oh, yeah, Dally did have blonde hair in the book, didn’t he? Huh.”

The case with Cloud Atlas is even worse, or at least, more fraught. Because, thinking back, despite how wrong his hair looked, Matt Dillon was actually really good in The Outsiders. He defined a different Dally than the one that I had known, but it was not a worse Dally, I don’t think. (It may have been a more sympathetic one, and so therefore less complex, so maybe that’s not so great. But I don’t know. It was a long time ago.) Indeed, Matt Dillon’s version of pouty emotional woundedness came to represent the essence of all of S.E. Hinton’s work on film, didn’t it? And I don’t think that is so bad, is it? Matt Dillon has gone on to become a real favorite actor of mine. (He was so great in Wild Things!) But Cloud Atlas happens to be starring Tom Hanks. Tom Hanks. Tom Hanks! Now, of course I loved Tom Hanks in “Bosom Buddies” and “Family Ties” and Bachelor Party and Nothing in Common with Jackie Gleason (especially Nothing in Common with Jackie Gleason) and Splash and all that. But then he became so Tom-Hanks-America’s-Favorite-Nice-Guy-Superstar around the time of A League of Their Own and Sleepless In Seattle. And Philadelphia, which, I admit to thinking he was very good in, but still. And then Forrest Gump happened, and everybody started talking in that horribly annoying mentally-disabled way he did in that movie, and I saw the movie, and I’m so sorry I did, because it makes you want to puke in your shoes and wash your eyes out with lye, but it won’t work. You can never unsee something like that. And then I remember seeing a full-spread two-page ad in the Times one day which showed him in that dumb white suit, and they’d made a huge American flag out of all the stars that different reviewers at different newspapers and magazines had given the movie. And it said something to the effect of, “AMERICA AGREES: FORREST GUMP IS THE MOVIE OF THE SUMMER! GO SEE IT AGAIN BECAUSE EVERYONE ELSE IS GOING TO SEE IT OVER AND OVER AND AGAIN.”

I remember seeing the ad and feeling more like I was living in a fascist, totalitarian state than I’d ever felt before. Fair to the man himself or not, I swore that day that I would never watch another Tom Hanks movie, ever.

(I have since broken that vow, I’m ashamed to say. I saw Apollo 13, and Saving Private Ryan, and Cast Away, which was good until Tom Hanks started talking, and — this really messed with my mind — I even really strongly very much liked a Tom Hanks performance, in The Road to Perdition. Nothing’s as simple as you want it to be, not even disdain.)

But still. Reliably vacillating between over-earnestness and simpering. Remember when he broke the fourth wall and gave the camera a gleaming little half-wink at the end of the trailer for Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close that was, in its context, so disgusting and shameless in its manipulation and exploitation of 9/11? That’s the second thing that, even though it probably wasn’t his fault, I’ll never forgive Tom Hanks for. (Well, maybe the third. I’ve never The Green Mile. But those trailers were traumatic, too.)

Soon, many of us, like David Mitchell himself, will be never be able to envision a host of the characters from Cloud Atlas as looking any other than like Tom Hanks, because, as we know from the movie trailer, he’s playing more than one of them. It’s not too late, though! The movie itself doesn’t come out until the 26th. Here’s the trailer. Don’t watch it if you have not yet read the book.

My wife, it turns out, was wrong. (Something that happens less often in our house than would be optimal.) I enjoyed Cloud Atlas very much! I didn’t find it pretentious or experimental or anything like that. Well, one part tells a story through an interview, but it’s not at all off-putting. And another part employs a heavy pidgin English that seems a bit strong, a bit too much like Uncle Remus at first, but once you get your bearings, it’s not so bad. If anything, actually, I would think its one of the more accesible books I’ve read in a while. It’s basically six different stories that take place at six different times, in six different places in the world, told in six different voices. But all of them are told relatively straightforwardly, and in unusually beautiful prose. The “Russian-doll” structure that people talk about a lot is novel (hey!): five of the stories are broken in half, and arranged leading forward in time up to the middle, and last story, and then backwards in time til the end of the book. But just the order of the stories, not internally within each. It’s not like Memento, or 21 Grams or that episode of “Seinfeld” when they go to India for the wedding.

The way the stories come together and reflect off each other, loosely, subtly, abstractly. More thematically, I guess, than anything else. (Unless I missed something, which is always possible.) It’s great, I’m telling you. (I’m probably not the first person to have done so. It’s a very popular book.) In fact, it’s a book that I have a hard time imagining anybody not liking. It’s action-packed and suspenseful. It’s got a little something for fans of all different types of books to like, and not a lot not to like. (I know one person that disliked it, who read halfway through and put it down. I have not yet talked to her enough about why. I think she got turned off at the start of the pidgin English part, and gave up too early.) It actually reads a lot like a movie, in the way that No Country For Old Men did. Well, it reads like six movies — which would seem to be the challenge of bringing it to the screen in under twelve hours. That’s one of the reasons I’m interested in seeing it. To see how they cut it down and put the pieces together. (Even when I know I’m bound to be disappointed. Curiosity vaporized the cat’s literary experience.)

I’m left perplexed by why my wife guessed I wouldn’t like it. You think other people know you. But they don’t. Not even your wife. No one knows anybody, really. Not that well. We’re born alone and we die alone, and we read books alone. You can watch movies with other people. And laugh or cry along together, or sneer and jeer and groan together. (In whisper voices, one would hope, if you’re in a theater. Just because there’s no God doesn’t mean we should be impolite.) I guess that’s one benefit of having the pure, mind’s-eye experience of reading colonized by the moving image. Laughing aloud with a bunch of other people in a crowded theater, many of them strangers, is one of the great pleasures of modern life, one of those times when we’re reminded of the ways in which we’re not totally alone, one of the bridges that connects us to other people and lets us know how much they’re like us. It wouldn’t be possible without the colonization. As text’s slide towards ambiguity allows for a more personal, intimate experience, film’s inclination to specificity opens it up for shared, universal experience.

Real-time communal experiences are not the only things that open up such bridges, though. The same miracle (or, as you may choose to think about, pleasant delusion), can happen through solitary endeavors, too. That feeling that I got that David Mitchell was spying on my thoughts — that serves as that same kind of bridge, too. And in so, reading ceases to be a solitary experience. And one that achieves a sort of loophole in the time/space continuum.

Or even just in talking to people, sharing ideas, about books and movies, say. Any time we feel like we honestly understand or sympathize with something someone else is saying (something that happens all too infrequently, considering how frequently its opposition carries the day, and how awful and lonely that feels.) Maybe that’s happened to you, at some point over the past six or seven hours it’s taken to read this blog post. Maybe you had that same feeling when you saw that Forrest Gump ad in the New York Times 18 years ago, and made the same promise to yourself, and then broke it. And are now feeling even the slightest bit warmed by the thought that I have been right there with you. In guilt and shame. It is my loftiest hope that this might be the case.

In the absence of faith in God, sharing ideas with other human beings in the only thing that pops the existential bubble wherein we spend most of our time. Even just for a moment, before they seal us up again in our essential solipsism.

(I guess when you take drugs you can get that feeling of communion with a dog or a tree or a patch of moss or the sky or the whole universe. That can be nice, too. But, again, it’s always fleeting.)

So hurry up and read Cloud Atlas, is what I’m really saying, before you see Tom Hanks stink it up, coming incredibly soon and surely quite loudly, in theaters nationwide.

Goodnight Earth

Would you like to take a tour of the earth from space? Then please allow Dr. Justin Wilkinson of the International Space Station to be your guide. Fair warning: If today’s shockingly dingy weather is making you sleepy, the twinkly music in the background here is certainly not going to do anything to help. Anyway, enjoy. It’s pretty beautiful. Yes, even the moon part. [Via]

"Quaffing a Round of Beers Is Arguably More Vital to Many Jobs Than Nailing a Round of Golf"

“I would call guys I was friendly with, guys who had their hands on big ad budgets, to see if they wanted to go to happy hour or get something to eat. And they’d say: ‘Are you drinking? No? Don’t worry about it.’”

— On the burden of having to drink for business. You know what they say: working in ad-sales

is just like being lead guitarist for the Replacements. Related, below: all the drinks of “Mad Men.”

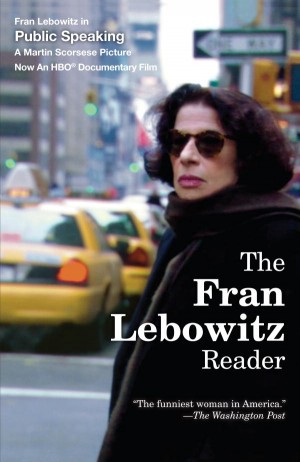

A Chat With Fran Lebowitz

Since the 1970s, writer Fran Lebowitz has been one of New York City’s most important social critics. In 2010, HBO aired Public Speaking, a Martin Scorsese-directed documentary in which Lebowitz opines with characteristic trenchancy on everything from the touristification of Times Square to the concept of fame to her dislike of digital clocks. Last month, Random House released an audio book of The Fran Lebowitz Reader, a collection of essays from her best-selling titles Metropolitan Life (first published in 1978) and Social Studies (1981). I recently spoke to Lebowitz by phone, and we talked about New York and its various incarnations over the past four decades.

MATTHEW GALLAWAY: Was it a challenge to record an audio book?

FRAN LEBOWITZ: A lot of writers complain about it, which I don’t understand. Compared to writing, it’s like a vacation. I mean, yes, I found it to be tedious.

Where did you record?

A studio in a place called the Film Center, which used to be an out-of-the-way place, 9th Avenue and 40-somewhere, I can’t remember. But now, of course, it’s smack in the middle of the 8-billion horrendous tourists. The thing I most remember about it as being unpleasant was that during that weeks I did it, the temperature was like 150 degrees, so that I had to sweat through Time Square to the subway in this horrible, horrible weather. But the thing itself, it’s just kind of tedious.

Could you smoke in the studio?

No, no, no. You cannot smoke inside anywhere in New York City, I mean, any place that you don’t own or rent or whatever. I smoked outside. Which the horrible thing about that, other than being outside, is that it’s in the middle of this incredibly crowded neighborhood there.

Did it take you back in time when you were reading the essays?

Yes, but not in a nice way! I mean, truthfully — obviously — yes. I don’t read these books very frequently, and so it was incredibly disconcerting. I mean, it would not be so bad if I had written six more books, but since that’s not the case, I found it disconcerting. The two books are now one book — The Fran Lebowitz Reader — and it sells very well. It’s in its 12th printing. And just from my own experience of being in the street, the majority of the people who stop me and tell me they have just read it, they are people who are young, and I don’t mean just younger than me, I mean people in their twenties. So truthfully, while reading, I kept thinking to myself, “they have no context for this, I don’t know what this means to them.” I don’t really actually care that much, but it’s an intellectual problem. When I was writing, my focus was a kind of contrarian stance to the counterculture, but to kids now, it represents the counterculture, and so I just think it’s a different thing. I mean, I know it’s a different thing to me. It’s just that they don’t have a context for it, and even at the time, most people didn’t, especially the pieces that were originally written for Interview and ended up in the book. Because in the early 70s, the readership of Interview could fit in one room, so it was less an audience and more of a clique.

One thing that really struck me reading the books was the gay world you described: you reference backrooms, discos, coded bandanas, Jean Cocteau, poppers, the baths, the Westside docks and trucks, Ronald Firbank — I mean, who’s heard of Ronald Firbank now?

My point is that even then no one had heard of him! My friends had heard of him, but we’re talking about a couple dozen people. I really think that just there happens to be a vogue now for this kind of thing.

Are you saying Ronald Firbank is back?

Ronald Firbank was never here. What I’m trying to tell you is that it was always beyond the special taste. I mean, even in Ronald Firbank’s era.

In the documentary Public Speaking, you describe arriving in New York and falling in with a group of mostly older, gay men. Talkers and wits, masters of the double entendre. Your essays really resonate with that kind of banter.

Yeah, I think that’s true. But you’re among the very few people who would notice that. I’m happy you noticed, I mean, “happy” may be the wrong word, but, yes, because people don’t even know. The memories of people are very short. As we know, because otherwise we certainly wouldn’t still have Republicans in office. People don’t remember things that happened in their own lives. I have friends who are my contemporaries, okay? They lived through the same era I lived through. They were with me. And yet I’ll say something, and they’ll go, “No, I don’t remember that.” Partially that’s a result of the drug taking, but partially some people just accept what’s happening and keep going. This is maybe a good thing for life, but it’s a bad thing for art.

In the documentary, you mentioned what AIDS did to the gay audience that used to exist in the city. Do you mean actual numbers, or an aesthetic, or both?

So truthfully, while reading, I kept thinking to myself, “they have no context for this, I don’t know what this means to them.” I don’t really actually care that much, but it’s an intellectual problem.

It’s not that there’s an insufficient number of gay men, it’s that they’re different. The point I’m trying to make is that this particular generation tied on a mask. There was a break in the culture. But additionally, the idea — and not just the idea, the actual life of homosexuals — changed immeasurably because of the acceptance of homosexuality. And that was because of AIDS. No one ever says that. Or how AIDS caused gay marriage. I mean, it would never have existed. You could pretend to your family that you were straight, but you couldn’t pretend you weren’t dying. And also, people became scared, not just of AIDS, which was a sufficient reason to be terrified, but also because — and this is the other thing no one ever says — the way that AIDS spread, by which I mean the rapidity, which was caused by a level of promiscuity that never existed before or since. And I really believe that people made these kinds of bargains with themselves. You know, I’m not saying I have this on the record but from what I could see from the people I know who survived that era, it was like, “don’t kill me and I won’t do this anymore.” Also, most straight people never thought about gay people before AIDS, which is why I could publish this stuff, go on a national television show and never be asked about it, in the way you are asking me about it. They would focus on other things. And after AIDS, I think that [homosexual] people were afraid of a kind of official response to AIDS, like they would be arrested, or put in jail, all these kind of things, which are not unlikely things, by the way, and so they made up a lie. “We’re just like you. We are just like you, we’re exactly like you.” But of course, they were not exactly like straight people. They were nothing like straight people.

How so, exactly?

At some point in the 70s, I remember being in an S&M; bar, I can’t think of which one, but in a bar with a friend of mine, a guy. Women were not allowed in this bar, so I had like a special dispensation. I was there as an anthropologist, let me assure you, and I said to him, “If straight people knew what was going on in here, they would send the army in.” I really believe that. It was a way of life for a relatively brief period of time that was stopped by AIDS, and it never came to public knowledge, because it was kept hidden. And it was hidden because people were afraid, and then these people died. I mean, there cannot be many who did not die, and those who were left just made this thing up. “No, we’re just like you, we just want to get married and have children.” And now gays are just like straight people. They’re just like them, or largely like them. The difference between gay people and straight people now has more to do with gender than with sexuality. Men are men whether they are gay or straight. And so, basically, I mean, to me, to see all these gay people with children, I can’t get over it. I think, “It’s unbelievable that you will do this when you don’t have to.”

You also reference a kind of lost era of cultural mentorship, where older gays would take the younger ones under their wing and bring them to the ballet and the opera, give them books by Ronald Firbank and so forth.

I mean, in a certain way, it depends where and when you were. This was more true in New York than San Francisco. In San Francisco, you had — how should I say this — a very “lively” scene. You didn’t have to be very smart, let me put it that way. In New York, being gay was not enough. Here, there was a hierarchy that had to do with intelligence or with a certain kind of cultivation. And partially this was caused by the invisibility of homosexuality in the culture. There was just no awareness of it. It just didn’t exist, but it also operated kind of like a secret society. And so part of the older men taking younger men to the ballet, part of that was — If you want to call it — mentorship and part of it was just seduction. So some of what you say was true, but not in the nice way you put it. There was a lot of hierarchy. Drag queens, for instance, who now are embraced in every living room in America, were generally considered very low on the social scale. There was a lot of contempt for drag queens, not all, but there was a certain amount of contempt, and it was considered to be a kind of a trashy thing to be a drag queen. Or to be a hairdresser — or other professions that were kind of conventionally gay professions at the time, like if you were a choreographer. Gay hairdressers were called “hair benders” and “hair burners,” and they were really looked down on because it was a “stupid” profession. By which it was meant a profession where you didn’t have to be smart, a lower-level profession. I also cannot stress enough to you how minute this world was. When I talk about it, it makes it sound like some sort of global thing, but it was very tiny. It was tiny here; and in every big city, there were similar scenes. But there was a big difference between cities, and certainly between a city like New York and a city like San Francisco.

I saw a documentary a few years ago about the Cockettes in which someone describes how, after the Cockettes arrived in Manhattan from San Francisco, they were hanging out one night in a bar and Candy Darling swept in and was just repulsed or disgusted by these “dirty hippies” and so she swept right out. Which I mention because it seems to epitomize the kind of hierarchy you’re describing.

That’s right, and, yes, I remember the Cockettes because I was an usher at the opening of the Cockettes. I desperately needed the money and I was supposed to be paid $90.00, which I never got, but among the people I showed to their seats were Gore Vidal and Angela Lansbury. The story is that someone saw the Cockettes in San Francisco, someone from New York. I can’t remember who, it might have been Truman Capote, someone like that, and he said, “You’ll see how brilliant they are.” And they came to New York. They were in a theater on Second Avenue, I can’t remember what it was called. There was a lot of hoopla about their arriving. In fact, I went to the airport to meet them in a bus. A press bus went from all the little, underground magazines. And until they performed, everyone loved them here. They were funny. The idea was that they didn’t try to look like women. Which Candy did. I mean, Candy was often mistaken for a woman, although really, to me she wasn’t a woman, she was like a big guy. The Cockettes had beards, okay? And so, that was the thing that was witty about the Cockettes, in my opinion. But their show was really terrible. And we had Charles Ludlam here. He was really brilliant! There were really brilliant people doing things like that here, and so the Cockettes, I think, the opening night was the only night that they performed. You never saw people turn so fast in your life. As everyone came into the opening, there was all this anticipation, everyone was going to love them, and within 20 minutes, it was over for the Cockettes.

If you were a teenage kid right now looking for some place to move, do you think it would still be New York City?

I don’t know. People are not so isolated anymore. Because of the Internet and because of the popular culture in general, where people actually are is certainly a lot less important than it used to be. There’s no question that geography is fast disappearing in a certain way. The New York that I came to doesn’t exist anymore. The little town I left is still there, but it’s as changed as New York is. So, it’s really impossible for me to imagine. There’s not the same need to go to cities as there used to be for some people, depending upon whether or not you like to live in cities, which I do. People don’t have to escape so much anymore. It’s not as restrictive to live outside of the big city now. There’s not the same kind of convention anywhere. It’s not that there are no conventions, but they’ve changed. It used to be that small towns were suffocating because everyone knew you and everyone was watching you, but that really doesn’t exist anymore, even in small towns. People don’t even know who lives next door to them. I hated being watched all the time as a kid. I really couldn’t stand it. But people aren’t watched like that anymore. No one cares.

Do you think it’s that nobody cares or that we’re too overwhelmed by the need to scrape out an existence?

It was shocking, especially because we were the only generation that thought sex was really good, like vitamins. We thought that about drugs too, okay? Sex was really good and the more sex the better. It was helpful. Like now, the way people think of bike riding, which I think is a childish activity.

Well, I think people always need to make money. There was not some utopian era where they gave you everything. But values have changed so much. Standards and values, everything’s changed immeasurably. It is as different a world as if we’d all gone to live on Pluto. So it’s really hard to make these comparisons. Or it’s inaccurate to make them is more what I would say. I don’t know what it’s like to be young now. I can observe things. But the generational observations that you make from this distance cannot help but be wholly inaccurate. It depends on where you start, and that’s what I keep telling my friends, my contemporaries. They say things like, “Well, kids now, they’re constantly texting and constantly on the Internet, and they don’t have conversations.” Or “they don’t have friends, they think a friend is someone they meet on Facebook. They never see their friends. They don’t know these people.” And what I would say to my contemporaries is that these kids’ definition of a friend is completely different than theirs. To me and my generation, it does not seem like a friend. To kids, it seems like a friend. They are completely different than we are in that way, completely different. And you see middle-aged people who are half in, half out. Like Anthony Weiner, the thing that happened to Anthony Weiner, I believe, would not have happened to someone older or younger than Anthony Weiner. He was young enough to use this technology, but too old to know how to use it correctly. Someone my age would not have used it in that way, I believe, and someone younger wouldn’t have made the mistake he made.

You don’t think politicians will have sex tapes in the future?

You mean people who are now in their twenties? They won’t care. People who are in their twenties will have already done this stuff, so there’s now a record. When those people are old enough to be in charge of things — which by the way I don’t ever want them to be in charge of things, and luckily, I will be dead when these people take over — everybody will have that vulnerability. When everybody is vulnerable to something it’s not a weapon. It’s like being gay. It used to be you could blackmail people, and now I would say no one cares. It’s hard to imagine an environment in which you could blackmail someone about being gay. It would have to be an environment of intolerance. Like the right-wing Christian preachers who tell everyone to hate people who are gay and then they turn out to be gay. So they’re vulnerable, but unless your profession is hating other people, you’re not really a candidate for blackmail anymore.

You’ve described having a three-decade bout of writer’s block. Do you ever worry that it might be permanent?

No. I don’t think that. Other people may think that, but I don’t think that, and luckily my concern about what other people think has never been that high. By the way, this is one of the things that I would not blame other people for thinking. But I do not believe that, and no one will ever accuse me of being a cockeyed optimist.

I’ve read about other artists and writers who lived through the worst of the AIDS epidemic and felt like they had to take a break from their art. While reading your book, I wondered if that might have been the case with you, because the world you described was essentially obliterated.

It is exceptionally charitable that you call these 900 years “a break” but I’ll take that. And yes, it was very shocking to live through. It’s always shocking to young people when their contemporaries die. Even in a war, it’s shocking. I mean, as a soldier. It was shocking, especially because we were the only generation that thought sex was really good, like vitamins. We thought that about drugs too, okay? Sex was really good and the more sex the better. It was helpful. Like now, the way people think of bike riding, which I think is a childish activity. I know people now think the bike is a sign of virtue and I think it’s a toy, but we said sex was good for you and it turned out to it could be bad for you. Really bad. And yeah, people became terrified, of course. People were “terror-stricken” is the term I would use. And because when you look at it in retrospect, like all things you look at in retrospect, it seems very linear. The great thing about history is that it’s in the past and people have time to compile a narrative, but that’s not how it seems when you are living through it.

Except you claim that people don’t want to acknowledge this shock and terror now, as part of the narrative.

It’s because there are hardly any survivors. This leap was made that was… I wouldn’t say “orchestrated” because there’s no way anyone could have imagined what would happen, but the behavior… Now look, when I say the “behavior,” I don’t mean the virus, okay? Because one thing that people really quickly forgot about AIDS is that it’s a virus. I did not forget this. I argued with the people from ACT UP and with all those people who made a kind of political activity out of something because they were afraid that the other side would make it into a political activity. I was always fighting with them and saying, “You are making a metaphor of a virus, which is what you were afraid that straight people were going to do.” But it was a virus. It still is a virus, like the flu or like a million viruses. So, I think that people stopped talking about it because there weren’t that many survivors, and because this big lie took its place, and this big lie was invented by people, not as a defense mechanism, but as a defense. Ronald Reagan was the president. Now he’s being looked upon as Santa Claus, but he was horrible, really horrible. And not just Ronald Reagan, but the world was made up of more Ronald Reagans than of anyone else, and so gay people were afraid and they made up this big lie. You know, “No, I haven’t had sex with 40,000 people in dark trucks, I’m just like you.” And so they didn’t invent the virus, but the spread of this virus, the rapidity at which it spread, of course it was caused by this promiscuity. Of course it was. It’s the same thing with a regular cold virus. If you’re alone in your house with a cold, no one’s going to catch it. If you go into a subway car and you sneeze on everyone, the subway car’s going to catch it. So there’s this blank space in history where the story breaks. In every kind of documentary or anything written about at the beginning of AIDS, they always show you that piece in The New York Times, someone in their house, Fire Island Pines, reading this headline. But that’s not how it was. And they show it because they don’t have time to explain, and five minutes after that everyone’s dying, and then two minutes later, everyone’s getting married. Okay? That is just not true.

The Awl is read by many people in the 25- to 35-year-old set. Anything you’d like to say to them in parting?

Well, when you get the power, if that ever happens, please change these stupid smoking laws. That’s my main message to them.

This interview was lightly condensed and edited for purposes of clarity.

Fran Lebowitz will be appearing at Town Hall on October 20 in a discussion about politics with Frank Rich. For a full schedule of her appearances, please visit her events page on Facebook.

Matthew Gallaway is the author of The Metropolis Case.