Go, Escaped Crocodiles, Go!

“Many of the crocodiles have been recaptured, but more than half are still on the loose.”

— Some 15,000 crocodiles escaped a crocodile farm in South Africa after the human owner opened the gates last weekend to prevent a storm surge during heavy rains. That’s a lot of crocodiles! These lovable creatures have been unfairly besmirched by their association with horrible footwear in recent years, and also by two guys from San Diego who write some nice songs but are far too derivative of Glasgow’s forever awesomer and underrated Jesus and Mary Chain.

I mean, gimme a break, right?

African crocodiles are famous in the animal world for being good parents. According to National Geographic:

“One unusual characteristic of this fearsome predator is its caring nature as a parent. Where most reptiles lay their eggs and move on, mother and father Nile crocs ferociously guard their nests until the eggs hatch, and they will often roll the eggs gently in their mouths to help hatching babies emerge.”

They are farmed for their meat and valuable skin — which is used to make belts and boots for people in San Diego. So the jailbreak is righteous and heroic in that regard. But of course, crocodiles also kill a lot of people. Like 200 people a year, making them one of the dangerous animals to humans on the planet. (Their salt-water cousins in Northern Australian tally ten times that!)

So stay away from the Limpopo River, humans. Give these things a wide berth.

The Joys And Derangement Of "F Troop"

The Joys And Derangement Of “F Troop”

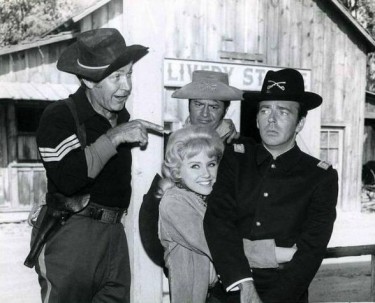

Fort Courage, Kansas. Civil War hero Captain Wilton Parmenter is in command, protecting the Fort, and the neighboring town of the same name, from a tribe of Indians in the area, led by Chief Wild Eagle. With Sergeant O’Rourke and Corporal Agarn rounding out his staff, Captain Parmenter navigates Fort Courage through the dangerous waters of the expansionist latter half of the 19th Century.

Plus also: wackiness.

This is the synopsis of a situation comedy, circa 1965. Not an emphatically successful one, but “F Troop” was still a pristine specimen of what I grew up thinking was the Platonic ideal of sitcoms.

This essay is part of a series about our favorite TV shows past.

Previously: Love And Other Conspiracies Of “The X-Files”

Here’s the thing about those Gen Xers like me and the pop culture ephemera we glommed from latchkey childhoods with pre-cable VHF/UHF television sets: we weren’t so much consuming entertainment as we were soaking in it. If you were old enough to watch TV in the early 70s, a large portion of the TV you were watching, particularly after school, consisted of syndicated reruns of old network TV. There were the locally produced kids shows with cartoons as well, but after that, until prime time (and aside from the local/national news), it was reruns. “Petticoat Junction,” “The Munsters,” “Beverly Hillbillies,” “Green Acres” and even “Batman,” these were shows that had long ceased production, but lived on to fill the holes in the schedules of each local station. Accordingly, your media training — those first doses of mass media that train you how to consume and unpack entertainment — was provided by TV shows that were five or ten years dead.

So of the menu of 60s TV I was exposed to, “F Troop” is what stuck, even though I was so young at the time I can now remember only characters and vague plot outlines. (When the show was rebroadcast on Nick at Nite in the early 90s I was busy watching “The X-Files” and “The Adventures of Brisco County Jr.”) And as far as the characters went, the cast was indelible, and looking over their careers, it was a very interesting bunch. Sgt. O’Rourke was played by Forrest Tucker, a character actor and veteran of action films. He was a big man, with a foghorn of a voice, who would later co-star in the mid-70s live action Saturday morning show “The Ghost Busters” (no, not those Ghostbusters, but ghosts were busted) with Larry Storch, the irrepressible stand-up comic who played O’Rourke’s foil, who had a long voiceover career and performs Broadway and clubs in New York to this day. The romantic interest, “Wrangler” Jane Thrift, was played by Melody Patterson, who was only 16 when she was cast. (Patterson maintains an old-timey official website which may be a bit out of date but is charming nonetheless, with the obligatory 9–11 e-ribbon, and the “Wrapping with Wrangler” column.) And Capt. Parmenter was Ken Berry, a song-and-dance man who came up through talent shows and Vegas, who was later a mainstay of Disney (Herbie Rides Again and The Cat From Outer Space) and Carol Burnett. It was his dance training that accounted for the clumsiness of Parmenter, tripping, falling over things, etc. An autobiographical nugget about Berry: Back in the 50s, he had served under Sgt. Leonard Nimoy (who encouraged Berry to move to LA after his service) in the Special Services Corps of the Army, and was later mentored by the likes of Andy Griffith and Lucille Ball. Overall the cast was a tight ensemble, and by all accounts a tight bunch on the set. (Here, have some bloopers.)

Interesting, so what? Well, the thing is, since I was watching “F Troop” in reruns, I would occasionally see one of the cast members in a different context contemporaneously. We saw the Herbie film in the movie theater, and I’d see Forrest Tucker and Larry Storch (and a guy in a gorilla suit) reteam up in the aforementioned “The Ghost Busters” while eating Saturday morning pancakes off a TV tray. The question this presented my little brain: how can these TV people be different people on different shows? I mean, that’s clearly O’Rouke and Agarn on that show about the ghosts. Streams were being crossed. Which led pretty quickly to a nascent understanding of how show biz worked, and still does. And all these years later, it’s a trip to look up these actors, three of whom are still alive, and just gaze at the paths illustrated by the various resumes, leading up to “F Troop,” and then following its cancellation in 1967 (which happened somewhat mysteriously.

An even more important lesson learned was from the casting and characterization of the members of the Indian tribe, the Hekawi. I was a little kid, so I was taking as gospel the depiction of the tribe: “Me not see White Man many moons” patois, one-liners dropping like F bombs, and shrewd in the ways of business. This was of course inaccurate (and objectionable in now obvious ways). However, considering that there was not a single Native American playing a Hekawi, it had a hidden logic: the actors were New York Italian and Jewish comics, and what they were doing was standard Borscht Belt schtick. Even the given name of the tribe is a routine — tribe wanders, falls off cliff, wonders, “We lost. Where the heck are we?” This was probably pretty clear, maybe even hilarious, to the grown-ups of the mid-60s, but it took me a couple years to parse that. But again, I was unwittingly introduced to a walk through show-biz history.

As an example, take this clip, a quick little two-hander featuring Chief Wild Eagle (Frank de Kova) and (really) Crazy Cat (Don Diamond).

And the structure of this particular sitcom was what I came to find out to be called subversive. It was not so much a family sitcom (like “Leave It To Beaver” and “The Dick Van Dyke Show”), but more of a “caper” sitcom. Long story short, Sgt. O’Rourke is the true protagonist of the show, and he runs the fort and the town like a benign kingpin, pulling the strings, calling the shots. Cpl. Agarn is O’Rourke’s right-hand man, so the non-commissioned officers are running the joint, with the help of the Hekawi, who are partners-in-crime with O’Rourke, and who would on occasionally stage fake acts of aggression for the Fort to “repel” so that Cpt. Parmenter could keep his job, as Parmenter was a well-meaning yet naïve clumsy oaf from a well-heeled military family, whose relative witlessness was unlikely to uncover O’Rourke’s enterprise anytime soon. It had its precedents, in “McHale’s Navy” and some of the plots of “The Honeymooners,” but it was my first exposure to what you could call an underground economy, where nothing is as it seems and the real action is not where you can see it. Of course I didn’t realize it at the time, but it’s a pretty useful situation to be sensitive to, out here in the real grown-up world. By way of illustration, I get a more clarified smack of the same insight when reading Neal Stephenson’s The Baroque Cycle.

It was a curious habit of the time to set comedies in deliberately unfunny circumstances. Think about it: were there now a sitcom based in the times of our slow subjugation of the indigenous peoples — or better yet, in a German concentration camp circa WWII — it would be not only considered transgressive, but also make “Louie” and “It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia” look as toothless as “The Big Bang Theory.” This subtle derangement was a gateway drug, one that led to an appreciation of popular entertainment that was a little more than straightforward. “F Troop” was a standard-issue TV product from soup to nuts, but the underlying sense of dislocation is the product of its time, and it’s what seeped into the little kid brains of the Gen Xers — at least the ones like me, parked cross-legged in front of the TV as big as a cabinet, unaware unaware of what “meta” was, or that someday “meta” would become a mild libel.

Previously in series: Love And Other Conspiracies Of “The X-Files”

Ladies Finally Can Die Just Like Men From Cigarettes (And Fighting Wars)

It seems like only yesterday that America’s women were finally allowed to be killed in front-line combat. But it was a hollow victory, as so many victories are, because after losing something like nine consecutive wars, America now fights its foreign battles using genderless drone airships that will never cry or come home unemployable.

But ladies can still die “like a man” without even being sent to Camp Victory:

U.S. women who smoke today have a much greater risk of dying from lung cancer than they did decades ago, partly because they are starting younger and smoking more — that is, they are lighting up like men, new research shows. Women also have caught up with men in their risk of dying from smoking-related illnesses.

Is there any point in quitting? Yes … but only to a point. Those who kick the habit by age 30 can get back all of their pre-smoking lung health, along with a life span similar to good people. But those who wait until 40 to quit will still die earlier, and they might even die before 40, of heart attacks or cancer.

The 'Times' Old Guard Makes a Break for Freedom!

Today’s the day that the New York Times must deliver unto the cost-cutters 30 heads — from the editorial side alone. Not just any 30 heads: preferably, big-league, non-union managers.

And they’ve nabbed a few volunteers. In particular, a big four: Jim Roberts, assistant managing editor and 26-year veteran; Joe Sexton, at the paper since 1987, Jon Landman, also at the paper since 1987, and John Geddes, at the paper since 1994. The departure of four influentialTimes editors clears out major institutional knowledge, and as well, in some cases, probably some much-needed emotional space. But really, this is a huge senior bench of the paper. Geddes is co-managing editor for news operations; Landman was managing editor, digital journalism. Also sports editor Joe Sexton is leaving. (LOL. Don’t worry about him, he’s going off to one of those plum ProPublica jobs. ProPublica is the Bloomberg Foundation of journalism.) These buy-outs are, if nothing else, incredibly disruptive. (Though there can be, again, an upside.)

What’s also amazing about this is it’s two off the masthead — three, if you count Rick Berke, who stepped off the masthead recently. That leaves three assistant managing editors, one managing editor and two deputy managing editors. (Though that could change shortly!)

Apart from that, long-timers Joyce Wadler, James Oestreich (at the paper for 24 years), Jacques Steinberg (since 1988!) and Alice DuBois are also off and running into the brave light of freedom. (Except Alice, she’s just going to BuzzFeeᴅ, same difference. (JK!))

But yes, you can do math. That’s eight people. So, 22 staffers to fire, unless some folks come forward in the next three hours. (And let’s not forget the business side, which everyone always does forget! Already the paper has discarded still new-ish yet expensive spokesbot Bob Christie.)

Don’t worry though, we can do this again in 18 months.

The Lost Art Of Opium Smoking: An Interview With Author Steven Martin

by Abe Sauer

Of all it has embraced, the booming artisanal movement has so far passed over one largely extinct 19th-century practice: opium smoking in the old manner.

But in a book out last year, one collector of antique opium-smoking paraphernalia documents how his fascination with a lost era’s artifacts led to an attempt to recreate and live in a lost era of chandu, resulting in an opium addiction of “the traditional manner” that reached a peak of thirty pipes a day. I spoke with author Steven Martin about his book, Opium Fiend: A 21st Century Slave to a 19th Century Addiction, his Opium Museum project, and the cultural legacy of a practice that went from one of the world’s most popular to practically nonexistent in a matter of a few decades.

Abe Sauer: In the book you state that you “wanted an exotic life.” While such quests for “an exotic life amongst the noble savagery of Southeast Asia” drives the backpacker circuit, you careened off the normal Koh Samui Moon Party opium-dabbler path. Why?

Steven Martin: The old “opium-dabbler path” was found up in the mountains, among the tribal peoples of northern Thailand and Laos. I seriously doubt anyone was doing opium at the Koh Phangan “Full Moon Parties”, but Western backpackers into partying no doubt made it a point to check out both venues. I myself wasn’t in Southeast Asia on the backpacker circuit. I’d been living there full-time since completing a four-year stint in the U.S. Navy in the 1980s. As I explain in Opium Fiend, I noticed the backpacker interest in opium smoking while working on updating guidebooks to Laos.

Opium smoking in the traditional Chinese manner had almost gone the way of the dinosaur in Southeast Asia — Laos was the last country in the region where a handful of rustic opium dens survived. But then the backpackers discovered them and made it profitable for poverty-stricken local addicts to open dens for the visitors — and these makeshift operations mushroomed along Laos’ backpacker trail. I passed word of the situation along to a journalist friend who was working for the Asian edition of Time, and he flew out from Hong Kong to do a story, hiring me as a translator and a fixer for the research phase. We spent some time in Vientiane, the capital of Laos, and it was there that I had what I like to call a “collector’s epiphany” and got the idea to start collecting antique opium-smoking paraphernalia. That’s how my big opium adventure began.

Abe: Your desire for the “exotic life” appears to not only have included geography but also the romantic aesthetics of the practice. For example, you tell of having a linen suit replica of the one worn by Tony Leung in The Lover.

Steven: The tropical linen suit was a direct offshoot of my opium smoking — I wanted to experience the vice exactly as it had been practiced in the old days. At first I put all my attention to gathering the correct paraphernalia. Once I’d accomplished that, I began to work on my surroundings and apparel. Me and an opium-smoking friend put thousands of dollars into recreating a 19th-century opium den, and whenever we smoked there we’d dress in period clothing to get the right atmosphere. Years later, when I found myself addicted to the drug, I began smoking alone and on a daily basis. But I never lost track of the fact that what I was doing was extraordinarily rare, and I used to get dressed up every Saturday — wearing my linen suit while reclining on the opium mat — as a way to remind myself to treat the old ritual with deference and formality.

Abe: Films that romanticize the opium smoking period feature in your story in a number of instances. But another you mention, a less than romantic film, is Apocalypse Now. Alex Garland’s 1997 book The Beach was also fascinated not only with this film, but the whole post-war, 1980s Hollywood Vietnam catalogue. You cite Now as a film that got you interested in Asia travel, just like the Beach protagonist. What gives?

Steven: I’ve never read The Beach, and I don’t know anything about it except that it’s a novel and was made into a movie that was filmed in Thailand. My first viewing of Apocalypse Now in 1980 was partly what inspired me to make my first trip to Southeast Asia — more specifically to the Philippines, where Apocalypse Now was filmed. I made that trip in 1981, a few months short of my nineteenth birthday. While I was in Manila I did a day trip to Laguna province where you could hire a canoe up the Pagsanjan River, where Marlon Brando’s commander-gone-mad scenes were filmed just a few years before. The jungle scenery was spectacular but by that time most of the film’s sets had already been destroyed or taken apart by scavengers.

Abe: Speaking of movies, a common complaint in the book is that so many films incorrectly portray opium smoking. During one smoking session, you fantasize about tutoring Johnny Depp “in the fine art of rolling” after seeing “his botched performance in the opening scenes in the film From Hell. Yet, you very recently had an experience with a film production studio that balked at spending a mere $600 to hire you and your collection to get it right. Why does it matter that audiences see this accurately portrayed?

Imagine somebody soaking a dried tobacco leaf in hot water and then drinking the result in hopes of replicating the experience of smoking a fine Cuban cigar.

Steven: I think an accurate portrayal adds credibility to a performance. Of course there aren’t too many people who will know whether or not an opium smoking scene is portrayed accurately, but myself and a handful of other collectors will.

The film you mentioned in your question will be based on a 1926 memoir by the pseudonymous Jack Black, a career criminal who operated in the western United States and Canada in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Black was an opium smoker, and so the props master got in touch with me through my website and asked about hiring me to consult. The props guy and I went back and forth for weeks, and because apparently the film was on a very tight budget, I offered to consult for $600 — almost nothing — because I was interested in the film’s subject matter and helping them get it right. And you know what? They turned me down. Six hundred bucks was too much to get a key element of Jack Black’s character right. But this is how producers and directors think. They’re gambling, rightfully perhaps, that their audiences will be just as clueless about opium smoking and its paraphernalia as they are.

Abe: Meanwhile, “Boardwalk Empire” did enlist your services. Why?

Steven: Martin Scorsese was the executive producer of the episode that I consulted for, and I understand he’s a stickler for historical accuracy. The opium-smoking scene was part of a montage at the end of Episode 5 in the first season. I think it says a lot about the quality of “Boardwalk Empire” as a whole that they would fly me from Los Angeles to New York and put me up in a hotel in Manhattan — not to mention renting authentic paraphernalia and paying me for a day’s work — all in order to get right a scene that lasted no more than a couple of minutes. But then, anyone who has watched the series will agree that the writing and research are nearly flawless.

Abe: One of the common images of the opium smoker is one of smacked-out, paralytic, horizontal destitution. Yet many smoked for recreation only.

Steven: The reasons for that stereotype are manifold, and, as with all stereotypes, they’re partly based on fact and partly on misunderstanding. During the heyday of the opium trade, raw opium exported by the British from India to China was purchased by Chinese brokers who then repackaged the product for sale to opium smokers within China. These brokers processed the raw opium into smoking opium, or chandu, and during this process they added impurities — the most common being opium ash — in the same way that drug cartels add nonessential ingredients to pure cocaine or heroin in order to boost their profits. Opium ash has a high morphine content, and adding it to pure opium not only increased the quantity of the product, it also made the high more numbing. So people with limited means who smoked low-quality opium cut with opium ash were more likely to lie around in a daze. And these were exactly the kind of smokers most often witnessed by Westerners living or traveling in China.

Another reason for the stereotype was the design of the Chinese opium pipe, which used an oil lamp as a heating source to vaporize the opium. The only comfortable way to hold the opium pipe over the lamp and monitor the drug as it vaporized was to lie down. However, pure, good quality chandu smoked in moderation was energizing, both physically and mentally. So the effects really depended a lot on the kind of opium being smoked.

Abe: And you argue that opium is no more harmful — and maybe less so — than alcohol.

The only comfortable way to hold the opium pipe over the lamp and monitor the drug as it vaporized was to lie down. However, pure, good quality chandu smoked in moderation was energizing, both physically and mentally.

Steven: No, not quite. Except for the very first chapter of Opium Fiend, my story is told chronologically and so my opinions and observations in each chapter reflect what I was thinking at the time. What I wrote was that during the time I was addicted to smoking high-quality opium, I felt that the habit was physically less harmful to the body than alcoholism. I also noted that my beliefs mirrored the opinions of H.H. Kane, a New York doctor who studied opium smoking in the dens of Manhattan in the 1870s and 1880s. But my views about the relative harmlessness of opium evolved as I got deeper into the habit and experienced how excruciatingly difficult it was to stop.

Abe: Opium “pipes” are still largely misidentified on “collection” sites and eBay. But from time to time one shows up for sale. How much work would it be for a person to assemble a working, traditional smoking kit?

Steven: That depends on how complete a layout we’re talking about. But even at its most basic, finding components that are functional might take years — especially for an amateur. These are antiques a century or more old, and even in pristine condition, they would need repairs to make them functional. And despite what I’ve done in the past, I think it’s wrong for someone who doesn’t know what he’s doing to make modifications to a rare antique just to try to get a buzz. I’ve seen pipes that should have been in museums damaged beyond repair by amateur collectors hoping to have some amazing opium experience. The only thing that bothers me more is the damage that antiques dealers do to old opium pipes and lamps by embellishing them in hopes of reselling at a high price.

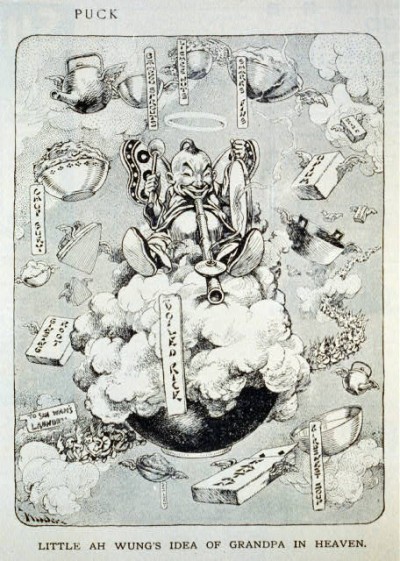

Abe: One of the more interesting points you make in the book is about the popular, but historically distorted narrative that imperial powers foisted opium on the unknowing Chinese. China in fact perfected the practice and imperial powers, like the British, only made it cheap and accessible. Why does this narrative persist?

Steven: One of my theories is that if it weren’t for the Chinese invention of the specialized pipe and lamp that made it possible for opium to be enjoyed recreationally, the British opium trade might not have happened at all. It certainly wouldn’t have been the moneymaker that it was. I’m no apologist for the British opium trade, but history is seldom black and white, and in my opinion history is much more interesting when it’s remembered and passed on with its contradictions intact. Why does this erroneous historical narrative persist? For the same reason they usually do: Painting itself as a pure and simple victim is strong political propaganda for one side (China), while the other side, the one that’s most to blame (Britain and other Western colonial powers), has no stomach for pointing out otherwise.

Abe: It was recently reported that opium cultivation is booming thanks to a spike in demand for heroin in China, where users have quadrupled in the last decade. (Meth use is also way up.) But the practice still seems almost nonexistent, though, recently, a Chinese official was charged with corruption and smoking opium “to keep up with late-night barbecue parties.” And while the word is still somewhat taboo in China, concern about the rebirth of the practice seems so tangential that state censors recently allowed a Chinese film (Wong Karwai’s The Grandmasters) to feature an opium smoking scene. Can opium smoking ever “come back?”

Steven: For a number of reasons, I seriously doubt opium smoking in the traditional Chinese manner will ever come back. For one thing, despite its having all but disappeared, regulations against opium smoking are still on the books just about everywhere. But another major reason is the difficulty involved in smoking opium — or, more correctly, vaporizing opium — in the traditional way. You need chandu, opium specially processed for vaporizing, and you need a set of this very specific and distinctive paraphernalia, and it has to be in working order. And once you have all that, you need somebody who can teach you how to use it.

I think anyone nowadays who happened to get hold of some raw opium would probably end up mixing it in their tea — but that’s just not the same thing. Not even close. Imagine somebody soaking a dried tobacco leaf in hot water and then drinking the result in hopes of replicating the experience of smoking a fine Cuban cigar. That’s what drinking opium tea is compared to vaporizing opium with the proper accoutrements.

And besides all that, people nowadays want instant gratification. Opium smoking is slow and old fashioned. I get the feeling that a lot of people are curious and would try it once if it were available to them, but how many would be obsessed enough to go to the extremes that I did in order to pick up an old-time opium habit? Very few, I reckon.

Abe: What advice would you have for somebody who read your book and, ironically, “wanted an exotic life” that included opium?

Steven: Good luck!

Abe Sauer is the author of How to be: NORTH DAKOTA. Photo of the author smoking opium; credit: Jack Barton. Illustration from the Library of Congress collection.

'New York Post' Full of Lies

Those “bundled-up youngsters who attend PS 10 in Park Slope, Brooklyn… joined by their parents yesterday for the icy trek to school” pictured in the New York Post’s attack on the school bus strike, as part of their ongoing anti-union campaign? “EVERY SINGLE THING about this is inaccurate. My kid and her friend were with our sitter (we do a nanny share, it’s great), who picks them up at school — neither of them were with their parents. I walk her to school every morning because it is two blocks from our house. We do not rely on buses. We are completely and utterly and thoroughly unaffected by the bus strike. “

Horse Burgers About As Healthy As Regular Burgers

“A drug that can cause cancer in humans may have entered the food chain through horse meat slaughtered in UK abattoirs, Labour has claimed.”

After 650,000 Page Views, CNN Decides Atheist Mom Is Okay After All

An atheist mom’s blog post on CNN.com was so controversial — imagine being a mother and not teaching your child to worship Jesus — that editors nearly removed the offending material. But the Texas mom’s reasons for raising her Texan child without religion “struck a chord,” meaning it went viral on the Internet. Some 650,000 page views later, there was a change of heart at CNN.com. Maybe an atheist mom should be allowed to keep her child, after all.

This week, she gained a whole new audience and the reassurance that she’s not alone. Her essay on CNN iReport, “Why I Raise My Children Without God,” drew 650,000 page views, the second highest for an iReport, and the most comments of any submission on the citizen journalism platform.

“Citizen journalism” means “content created for free, by a publisher’s own audience.” It is nothing less than a media miracle.

Photo by Eric Ingrum.

"Zinging The Chubby" Something Less Exciting Than I Initially Thought

“Zinging the chubby does not require a shift in our daily conversation. Plenty of Americans are already more than willing to chide their fellow fatties about their weight.”

— The head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Langone Medical Center expresses opposition to the idea that shaming the obese might cause them to lose weight.

It's "Take Your Flu To Work" Day!

Now that everyone’s been enormously sick, and for such a long time, we are all tired of staying in our homes in our segregated sickbeds. Let’s just take our flus to the subways and to the offices of Manhattan! I mean everyone else has it, so why should we worry, AM I RIGHT? And besides, what if they forget about you at work and lay you off? Here’s that attitude: “I work in a huge company, in a giant skyscraper, in the middle of Manhattan. I would say that in a typical day, 100% of my co-workers come into close proximity (on the subway, in the streets ,in the lobby, on the elevator, throughout the office, etc., etc…) to hundreds of people and the various concoctions of germs, bacteria, and viruses that these hundreds of people are transmitting. So, if you add me to the mix, does it really make a difference?”

Hee, I can hear everyone screaming “herd immunity” at once. Um yes, it does make a difference, ya ding dong. Here’s some pretty good responses.

My daughter is immuno-compromised, and people just would not stop coming into work while sick. I took to wearing a hospital mask at work to avoid catching anything, and I had to do a whole decontamination routine before I could see her, let alone touch her. Do you know what it’s like to see someone crying for you and have to stop yourself from reaching out to her in return until you’ve sufficiently de-loused yourself of the germs of one martyr of a coworker?

And:

I’ve been taking heavy precautions this year (the cruel thing about being immune compromised is that you don’t produce as many antibodies as healthy people do to the flu shot; it’s less effective for us), and I don’t go out much anyway. Nonetheless, I got the flu from my husband, who is not compromised and works in a large office where people come in sick. While he shook it off in four days, I’m going on two weeks. I’m so sick I’m getting IV fluids, IV electrolytes and anti-nausea medication at home. It totally almost killed me. I am like a walking, talking (swap: laying in bed and barfing) PSA for why healthy people should stay in if they are sick and contagious with the flu.