Death Cab For Youth: Getting Older With Former Sadsack Ben Gibbard

by Jen Girdish

For my thirty-third birthday, my husband pre-ordered “The Barsuk Years,” the Death Cab for Cutie vinyl box set. “That way you’ll only have the good ones,” he said.

He said “good ones” with an uptick in his voice, almost as if he was asking a question. Neither of us can tell how much of the gift, or any part of it, is a joke. I opened up the box, and I laughed. I love these records. Or: I loved these records?

It’s a time in music — or a time in music for me? — when the definition of Good Music has never been murkier. Are these the good ones? The idea of “good ones” just surfaces a lot of questions for which I don’t have an answer.

“The Barsuk Years” box set was scheduled for release a month before my birthday. It arrived two months late, and the manufacturer mislabeled the records. What’s labeled as “The Photo Album” is really “The Stability EP.” “The Stability EP” is actually “You Can Play These Songs With Chords.” It goes on. Artist in Residence, the company that released “The Barsuk Years,” specialize in high-end collectors releases aimed at the sort of person who would like to pay $95 for a copy of Julian Casablancas’ solo album “Phrazes for the Young.” A+R has promised a fix for the mislabeled records at an unspecified time in the future, but I’d rather keep them this way. It seems fitting that what I want to hear from Death Cab might not be the reality of what comes out of my speakers.

Ben Gibbard — Death Cab’s lead singer — has another archival release this year, which has received a bit more press attention: it’s the tenth anniversary release of “Give Up,” the first and only Postal Service album. (Also: one of only three platinum records in the history of venerated indie label Sub Pop.) Funny or Die released a fake Postal Service audition “tape” in its honor. The conceit of video: what if Ben Gibbard, darling of the sadsack Seattle scene at the dawn of the mainstreaming of indie rock, had to audition to be the frontman for that collaboration with Jimmy Tamborello? The fictitious jackass Sub Pop exec in the video casts a wide net for potential superstar collaborators: “Weird” Al Yankovic, Sunny Day Real Estate/Foo Fighters bassist Nate Mendel, Moby at his shirtless “Animal Rights”-iest, and an alarmingly Bowie-looking Duff McKagen. Aimee Mann is the only one who doesn’t seem like she’s joking, bringing a similarly gentle energy to “Clark Gable” that Gibbard eventually would, once he got around to writing it. Inevitably, Gibbard takes the stage in a wig that harkens back to his longer, devil-may-comb hair from the early aughts and starts crooning.

I watched the whole video through the slits between my fingers, waiting for the punchline. But there wasn’t one. Gibbard sings a couple of verses of “The District Sleeps Alone Tonight,” and Jimmy Tamborello picks him for the bleep bloop team. Did I miss something? Was the punchline the awkwardness of watching someone willingly put on the trappings of their past as if it were a theme party?

A few years ago, I played a game with some friends speculating what one would wear to an early aughts theme party. We suggested white belts, slightly mussed fauxhawks, boys in too-tight t-shirts, and girls wearing jeans under dresses? But it turns out that the biggest signifier is Gibbard’s side-parted bowl cut.

It’s ten years since the Postal Service album and ten years since Death Cab’s fourth album “Transatlanticism,” when I started tuning him out, and I haven’t had as many opportunities to stare at him in the intervening decade. He doesn’t look the same as he did a decade ago, but not in a predictable older, grayer style. He started running marathons, got sober a bit over five years ago, got a haircut. He doesn’t look like the older version of himself, a guy who used to croon about wearing long johns under his slacks. He looks like a stranger. It reminds me of when I was six and my father shaved his beard and I didn’t recognize him. Seeing Gibbard’s face everywhere is starting to make me feel unhinged.

Ok, Injury I’ve Been Running On For 10 Months, you win. #timeoff #healthyself

— Benjamin Gibbard (@Gibbstack) May 14, 2013

The first time I saw Death Cab was in a warehouse in Pittsburgh on Route 28. It was in early 2001, the cover was $5, and the warehouse didn’t have a bathroom. My boot-flared jeans were too long for my legs and dragged on the probably-asbestos floor, and I had to pee for two hours. There were about 25 people in the audience. (So yes: that story.)

A few months before the show, I had heard “A Movie Script Ending” coming out of my boyfriend’s speakers. I was writing notes for a fiction workshop, and the sleepy hook of “high-way, high-way” repeated over and over so often that I started scribbling “highWAY” in the margins. It was so melodramatic and perfect and I started laughing. My boyfriend was offended. He thought I was making fun of the song.

He said he was going to go see them, and he offered to take me only if I didn’t laugh.

Besides the way he folded a hook into a song, there was something about Gibbard’s stage presence that I connected with. He didn’t look like a frontman — he seemed like a shy boy in a pair of $10 thrift jeans that I dreamed up in my bedroom. Looking like an average nice guy seemed incredibly daring to me at that time.

So I saw Death Cab more times than I have any other band: in Ohio, and Texas, and I once traveled to Washington to see them at the Sasquatch Festival. I remember driving two hours back to my Seattle hotel room, trying to drive my friend’s stick shift while he slept. I listened to “The Passenger Seat” over and over, wishing I was in one, but excited about being exhausted and doing something I didn’t know how to do.

Death Cab weren’t the voice of a generation, or the now-controversial phrase “a voice of a generation,” but they captured the moods of the nameless youth trapped between Gen-X and the Millennials who wanted to stand out from the families and friends they left behind in their small Midwestern towns. Their lyrics were about navigating the lo-fi intangibles of your twenties. There was “something” about airplanes, champagne from a paper cup was “never quite the same,” you were only “pretending to read.” You may have had an invitation, but “you were never invited.”

The thing that was important to me about the wave of Northwestern indie bands Death Cab came up with was that they glorified sad sacks and mostly steered clear of gender demonizing. The love interest was (mostly) “you,” not “her.” I was just starting to appreciate the importance of gender-free pronouns. The demons in the early Death Cab songs weren’t girls, they were deadbeat parents, rancid but necessary house parties, the city of Los Angeles.

2012 was ‘You Do You.’ Motto for 2013:’Recognize Your Vibe.’

— Benjamin Gibbard (@Gibbstack) December 31, 2012

For as many times as I saw Death Cab, I never saw the original Postal Service tour in 2003. My friend Jessica had two tickets to the show at the Mercury Lounge on Sixth Street in Austin, a venue that, like the reason why I couldn’t go, has been lost to redevelopment. But here’s what I think is the reason. The Postal Service was when I started to question what I understood to be good music. I knew someone who knew someone who knew which “gaudy apartment complex” Gibbard sang about in “The District Sleeps Alone Tonight.” At the time, I thought that meant that too many people knew about the band. I should have gotten the hint then that liking bands didn’t individuate me from people as much as I thought it did.

And anyway, “Such Great Heights” was a summer anthem, and up until that summer, most of my music choices had been about not being part of a summer anthem. I had started listening to Death Cab because they felt pretty autumnal year-round.

The last time I saw Death Cab was in a medium-capacity venue in Kansas City sometime after “Transatlanticism.” Most of the people in line with me were under 21 and Chris Walla and Ben Gibbard looked as if they were wearing jeans they bought first-hand. I remember thinking as I stood in a sea of hands with underage stamps: this isn’t my band, this is someone else’s band.

Then Death Cab went hi-fi and were playing for real-live cuties on “The OC” and The Postal Service was, for a solid year, in the soundtrack of every TV show, movie, and commercial. Gibbard not only moved to the place he sang about not wanting to live, but he married a Hollywood actress, renounced his “unhealthy lifestyle” and took a role in a movie directed by TV star John Krasinski.

After 2011’s “Codes & Keys,” and then the end of his 26-month marriage to Zooey Deschanel, the Internet has made a part-time job out of tearing Gibbard down. Last year, Hipster Runoff put him on suicide watch. I wonder if this piling on of Gibbard would be different had Death Cab had broken up after they left Barsuk in 2004, if I wasn’t just pretending “The Barsuk Years” box set were the only records they made. A lot like that in-between generation, Death Cab was a band that straddled the continuum from being a “legacy indie band” to sticking around long enough to get big. But unlike like Built to Spill, Wilco, or Modest Mouse, it seems now like the internet is embarrassed by Gibbard. It’s like everyone is mad at him because he reminds people that who they were ten years ago could now be a rather sad little theme party. The trendy generational markers might not be as vivid as a white disco suit or a giant clock around the neck, but they age just as badly.

grey nose hairs

— Benjamin Gibbard (@Gibbstack) May 29, 2013

Yet when I’m nostalgic for being 22 or 23, I will more often than not reach for The Postal Service. Death Cab sounds a little too gauzy, now that it’s baked in the sunlight of a decade. The Postal Service have a durability, especially for a side project, and they are now canonized by the nostalgic indulgence of a reunion tour. In 2013, it’s hard to argue with the force of a summer anthem, and it’s hard to keep arguing about whether or not an indie band is good when their album goes platinum.

What kind of music do I want Gibbard be making right now? Did he have a long-run plan? Is he still hashtag relevant? Was he really the one worth leaving? When Gibbard released a solo album after his divorce, I read some speculation that it would be full of “more sad Death Cab songs.” I don’t want that. To me that would be a different kind of sad. Sad like a thirty-six year old who’s still drinking champagne from a paper cup, crashing on your couch when the party’s over. I want him to be happy, and I want him to embrace his age. Because we are all getting older: tonight’s Postal Service show in Salt Lake City was canceled “due to illness,” Gibbard announced today.

I recently read a trend piece in the Globe and Mail about a few people referring to their thirty-third year as their Jesus Year — and not because Jesus died when he was 33, but as a nod to the year that he accomplished the most. I prefer to think of it as my coming-to-Jesus year. If I cared about my favorite band shilling their songs in a commercial, I might have nothing left to listen to. I’m the kind of person who owns a fetishized box set so I can reimagine a discography. Pronouns free of the male gaze aren’t enough for me anymore, I want to listen to frontwomen, not frontmen. Beyond still getting excited about what Karen O’s fashion choices — also more than ten years later, of course — I don’t choose to see bands because of what they’re wearing or where they bought their jeans. I don’t mind running to the bathroom during a set; I’m not afraid to miss anything. I love to sit down at shows, and I love the moment when I remember that I bought seats instead of general admission. Which I remembered to do when I bought tickets to see my first Postal Service show in two weeks.

Like “The Barsuk Years” box set, I can’t decide if going to see the Postal Service is a joke or not, but I’m going to face Gibbard in his decent jeans and neatly trimmed locks. When you spend hours of your formative years listening to a band in your bedroom, singing the soft hooks to yourself, it’s hard to separate your own meaning, your place in the world from theirs. When he steps on the stage, I hope that that I stop wondering if he’s okay. Because when I wonder if Gibbard is okay, I wonder if I’m okay. So what: I was 23, and now I’m 33. There was something about Death Cab for Cutie, Ben Gibbard, and about that time. Now, there’s not. He really meant something to me, and now he doesn’t.

Jen Girdish is worried about a lot of things. Read about them here. Photo by David J. Lee.

New York City, May 29, 2013

★★★★ Gray fog turned into blue haze, dirty in the southern distance down the avenue. Late morning was still a little cool, more pleasant than it looked like it should be. Things got warmer and warmer, but were always preferable to the indoors. The sun was a glow sprawling all over the western sky, forcing the eyes down and away. How was anyone supposed to appreciate the solar alignment with the Manhattan streets if the light was coming from everywhere at once? The thick air was soothing on the skin and contentious on the nose: garbage, cologne, cooking. As it lowered, the sun pulled itself together. Golden light poured sideways across the apartment; the kindergartener did a dance with his perfectly matched shadow on the bedroom door. A magenta disc made the final descent — or half a magenta disc, sliced vertically by a building in New Jersey, with no regard for the grid.

A Poem By Lina ramona Vitkauskas

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Flash-Sensitive

It was obvious.

By March 2011, I was not projecting into the fourth quarter.

That very day, several juvenile delinquents kicked

the locks off the shed door where I lived and I dragged them

all in by the ears and showed them Magritte’s umbrella collection.

Then, from behind the rusty chipper, I revealed my “associate”

while puffing on my own gentlemen’s brand of cigarillo. One stray

stayed, I made porridge, made a leather fist and slammed his beer

into the table. “Come work for me,” I said, “you’ll erect a greenhouse

in back.” Later I wandered into town & arrived at the meeting of the

Itty Bitty Titty Committee, where I gladly introduced them to igneous

and conglomerate rocks. Meanwhile, the stray juvvie gingerly secured

my dress to the clothesline — out of respect. He suddenly saw little flash-

sensitive Diane, from next door, in the inflatable pool

smell pliable plastic he knew her from phonics & braids —

green grapes in paper sacks. Diane & I made confections from the

finest mixes & jams back then, but the townsfolk shamed

us (our foul mouths) & ordered us to spit into the divine

volcano, as children are often ordered to do in New Guinea.

We then heard Agent Cooper say, “Diane, I’m looking at

what appears to be a package of chocolate bunnies,” and

every morning, our amphibious wings bled into the months

we had not slept. We look back now & say, “Mahogany … wow…”

So get into the circle tell us about yourself.

Lina ramona Vitkauskas is the author of SPINY RETINAS (Mutable Sound, 2014); A Neon Tryst (Shearsman Books, 2013); and THE RANGE OF YOUR AMAZING NOTHING (Ravenna Press, 2010). In 2009, Brenda Hillman selected her for The Poetry Center of Chicago’s Juried Reading Award.

Outside hot. Inside poems. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

What Australians Learn In School

Good lord, Australia, stop pelting your Prime Minister with sandwiches. I mean, unless that’s a sign of respect down there, which given everything we know about that country it probably is.

Man Declares Summer

New York’s “what’s that smell?” season has officially begun.

— Paul Werdel (@prwerdel) May 30, 2013

[Spoiler: It’s piss.]

Marvelous Spinster Barbara Pym At 100

A note in Barbara Pym’s diary instructs: “Read some of Jane Austen’s last chapters and find out how she manages all the loose ends.” Next entry, a fairly typical one: “The Riviera Cafe, St. Austell is decorated in shades of chocolate brown. Very tasteless, as are the cakes.” This was written in 1952. She was 38, had published two novels, Some Tame Gazelle and the resplendent Excellent Women, and was at work on the next. It had taken 15 years of dutiful revising and circulating it around for Some Tame Gazelle to find a publisher. During the rewrites she had tried to heed her agent’s advice to “be more wicked, if necessary.”

This Sunday, June 2, marks the centenary of Barbara Pym’s birth: If you aren’t lucky enough to be with the Barbara Pym Society in Oxford, you could make something from her cookbook (downloadable!) or just read one of her novels with champagne, tea or your hot milky drink of choice.

For new Pym readers: I’d start with either Excellent Women or No Fond Return Of Love. Other nice starting points: A Glass of Blessings, Less Than Angels, and The Sweet Dove Died. Do not start with Crampton Hodnet.

During her 20s, she’d completed several other books, including a Finnish novel (she’d never been to Finland) and a spy novel written during WWII, which was very good except for the actual spy parts (she had never met a spy). During the war she’d been placed in the Censorship Department, then joined the Wrens; she now lived in London with her younger sister Hilary. She didn’t expect to make a living off her writing. She worked at the International African Institute in the editorial department, managing its journal and ushering various “dusty academic” anthropological monographs and studies through publication. Only a handful of the anthropologists she worked with knew or appreciated that the woman overseeing their indexes and edits was one of Britain’s great comic novelists. Many an acknowledgement went: “I am grateful to Miss Barbara Pym for the considerable work involved in preparing the final version of the text for the printer.”

This is all so worthy, so stealth, so Pymian! Hazel Holt, her friend (and later biographer and literary executor), shared an office with her at the Institute. In her life of Pym, she describes their conjectures about the home lives and backstories of their Institute colleagues, the Anthony Powell Dance to the Music of Time quizzes they’d give each other in the long afternoons, how Pym would repurpose old galleys as stationery for typing her novels. Once an anthropologist, visiting their office, told them that years before he’d been to a party Virginia Woolf had given. The two leapt on this: glamorous brilliant Bloomsbury, what had the party been like? “But, alas, all he could remember was that the refreshment had consisted only of buns and cocoa.” This, too, seems very Pymian.

Another Pym thing is always to be a little in need of a revival. One critic-friend, attempting to spark interest in her novels after they’d gone out of fashion in the early 70s, recommended them as “books for a bad day.” And they are, it’s true. They’re comforting and deeply funny. Try to describe them, though, and they go all muzzy: curates and jumble sales, tea urns and “distressed gentlewomen.” (You can make Wodehouse sound similar with this sort of inventorying: country houses and cow creamers, prize pigs and school prizes.) Their human values — modesty, compassion, generosity, stoicism — are quiet. Worse, they’re so beautifully crafted, so stringently revised and edited, they appear deceptively as if they had been easy to write. What’s hard to get across is that Pym’s novels are, basically, spinster drag novels — the emotions quite genuine and at the same time a send-up, a pose. Love, Melancholy, Poetry, and Death, all the most Romantic Trappings, courtesy of the vaguely nice-looking lady in dowdy shoes at the next table who you didn’t notice jotting down everything you said into her little spiral notebook.

“Let me… add that I am not at all like Jane Eyre, who must have given hope to so many plain women who tell their stories in the first person,” says Mildred Lathbury in Excellent Women.

***

Barbara Pym and Henry Harvey

“Henry has bought a book about neurosis and is relieved to find that his neurosis differs in kind from psychosis and madness.” This happy neurotic news was from a friend of Pym’s from her college days in Oxford, the writer and critic Robert Liddell, on a road trip in East Anglia. The “Henry” of the letter was Henry Harvey, exasperating object of Pym’s unrequited love in her 20s, temperamental, brilliant marvel of their set of friends. Henry wrote her letters in “Latin, German, French, Swedish, Finnish and the English of James Joyce” that “I could not well understand.” Other times he didn’t answer her letters at all. He was that guy. They had a lopsided on-off-on relationship at Oxford and, later, a long friendship — the former a source of great pain and anguish to her. When Henry eventually got married, to a girl he’d met in Finland, Liddell sent a note care of Pym’s sister so that she could delicately break the news. He typed the address on the envelope so that Barbara wouldn’t recognize his handwriting. (Later, delightfully, Liddell got off the great deadpan line: “Surely Henry will wear out more than one wife.” And when the foretold divorce eventually came to pass, Liddell wrote to her, “what a relief it is to write irreverently of Henry and how angry he’d be! Like people making fun of the Devil.”)

Many of us have fallen for a Henry. What’s marvelous with Pym, and why it seems worth bringing the affair up, is that even when she was at her most besotted — referring to him as “Lorenzo” in her diary (Lorenzo!) and hotfooting after him around Oxford and stationing herself in the Bodleian reading room he frequented and then getting tongue-tied if he spoke to her — there remains something so wonderfully keen-eyed and akilter in how she observes him.

Oh ever to be remembered day. Lorenzo spoke to me! … He talks curiously but very waffily — is very affected. Something wrong with his mouth I think. — he can’t help snurging. … Then I said, ‘By the way I hope you don’t mind my calling you Lorenzo — it suits you you know.’ ‘Oh does it — how awfully flattering.’ He snurged and went on up the Iffley Rd while I walked trembling and weak at the knees into Cowley Place.

Oh ever to be remembered day. He snurged and went on up the Iffley Rd.

A later entry, just a single line: “What a bad sign it is to get the Oxford Book of Victorian Verse out of the library.” All the Pym hallmarks are in place. The snurging, fatuous hero; the heroine with her painful, unrequited love; the turning to poetry for comfort.

It wasn’t long after Harvey married that Pym started referring to herself as a spinster. Not just once but many places. This from a long, jokey, highly stylized, meant-to-impress letter she wrote to Henry, his wife Elsie, and Liddell, all together in Finland: “… and this Miss Pym, this spinster I was telling you about, is sitting outside in her green deckchair and she reading Don Juan and smoking a Russian cigarette (she is quite a dog, this old spinster)…” She was 24 then, that old spinster, already at work on Some Tame Gazelle, where she had, as it happened, cast herself as a spinster of 50 living with her sister next door to a former boyfriend named Henry, now married to a formidable rival. Pym had received a couple offers of marriage from other boyfriends; some of them hanging around while she was hightailing after Lorenzo up Iffley. She turned them down. She didn’t love them was part of it. But I also suspect, that on some level, she simply didn’t want to be married and have children (she never cared for children, always preferring cats). She wanted to write books, and while that certainly wasn’t an unheard of endeavor for a woman of her time and education, it was rare. Pining for Henry (or whoever) and throwing a spinster mantle — or cardigan, rather — over herself allowed her to maintain her independence, even while the remembrances stirred by the almost-romance fueled her books. “I’m beginning to enjoy my pose of romantically unrequited love,” she wrote in her diary after poring over some love poems in the Bodleian while thinking of Lorenzo.

The pain was sharp, biting, Romantic — and also narratively severed from its object. From one of the unpublished novels she wrote in her 20s:

Flora often wondered what would become of her. She had been in love with Gervase for so long that she could not imagine a life in which he had no part. Nor, on the other hand, could she imagine a life in which he returned her love. That would somehow spoil the picture she had made of herself, it was an interesting picture, very dear to her, and she could not bear the idea of being spoilt. Noble, faithful, long–suffering, although not without its funny side, it was like something out of Chekov, she thought. The first two years were the worst, she reflected calmly. She could tell any young woman that. But it was really no use entering upon an unrequited passion unless you were prepared to keep it up for at least five years. Seven years was best. There was something very noble about loving a person for seven years and getting nothing in return.

For all he was self-absorbed, Henry was perceptive about this current. In 1985, five years after Pym’s death, he gave a talk at PEN America about her (pause here for horrified imagining of your most painful, youthful crush giving a literary talk about you: “Yes, I’m the snurger of the diaries.”). About his memories of her as a young woman he said:

‘Being-in-love’ and ‘being-in-Oxford’ were better kept at pretend play. That way they could be turned into art.

She was tempted I think sometimes though. Oh the luxury of giving up, of giving up pretend play with all its elaborations, of becoming just a participant, an actor in life, in mere lazy undemanding life.

But the other side of Barbara won, the observing, creating Barbara doing her pretend playing in her writing and doing it so well.”

One lovely thing is how long their friendship lasted. At age 38, when she was feeling very confident with her writing when she wasn’t reading Jane Austen to remind herself how to tie up her plot loose ends, she addressed him tartly: “Now we can be mean to each other — I by not giving you a copy of my new novel and you by not buying it.” Much, much, later, near the end of her life, when he, now twice divorced, was living near her house in the country, they’d go on platonic weekend trips together. He recorded: “We looked in other hotels to see what people were eating.” He was, by that point, even writing in his diary like a Pym character.

***

The outset of the war in London made loss seem inevitable, too.

A 1939 diary entry:

So many places where one has enjoyed oneself are no more — notably Stewart’s in Oxford — shops are pulled down, houses in ruins, people in their marble vaults whom one had thought to be still living. One looks through the window in a house in Belgravia and sees right through its uncurtained space into a conservatory with a dusty palm, a room without furniture and discoloured spaces on the walls where pictures of ancestors once hung. One passes a house in Bayswater with steep steps and sees a coffin being carried out.

This is part the tug of sadness that makes itself felt in the novels, splendidly funny as they are. Life, one of her heroines notes, is “comic and sad and indefinite.”

***

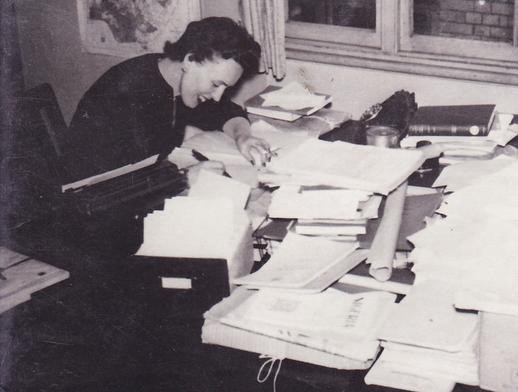

At her desk in the International Africa Institute.

At the Institute, she was a writer among anthropologists, and she adopted many of their techniques. In her biography, Holt notes that Pym especially relished this line from a handbook called Notes and Queries in Anthropology: “Not even the slightest expression of amusement or disapproval should ever be displayed at the description of the ridiculous, impossible or disgusting features in custom, cult or legend.” Even before she joined the Institute, her diary had read like field notes. Notes on parties and dates, the comings and goings of crushes — their appearances deftly sketched in, their habits noted — are made, but the observing eye soon started to include random strangers and acquaintances. She was always curious. She was perverse in her attachment to the unfashionable middle-class, the ordinary — all the interests that would later make it easy to overlook her writing. “On the hottest day of the year I saw two nuns buying a typewriter in Selfridges. Oh, what were they going to do with it?” In the diaries, she doesn’t manage to hide amusement, but she’s a steadfastly kind, benevolent observer all the same.

Some of these flares of curiosity extended ongoing “sagas,” where she and her sister Hilary would track the lives of strangers for a period, creating elaborate stories about their lives and arranging sightings. (If she lived now she’d probably satisfy a lot of this narrative urge online. “Barbara Pym is now following you Random Person With Interesting Twitter.” I also regret she didn’t get the chance to Google-stalk. She would have been masterful.). For a time, they were obsessed with the comings and goings of two of their neighbors, a gay couple who lived with a little dog a few doors down. One weekend, in temporary possession of a car, they followed one of the men, who mysteriously (to them) drove off every Sunday wearing a cassock. He turned out to be a church organist: “After the service they were swept up with the rest of the congregation, into the church hall for cups of tea, and found that they were being welcomed enthusiastically by the vicar’s wife, holding a jar of sugar and a pink plastic apostle teaspoon.”

The four later became friends, which, Holt notes, was awkward. She quotes Rachel Ferguson’s novel, The Brontës Went to Woolworths, which has a similar type of saga-building as its plot: “The main trouble lay in the fact that I came to [her] aware: primed with a thousand delicate, secret knowledges and intuitions, whereas to her I was, I suppose, merely so much cubic girl, so to speak.”

This practice of observation, of jotting even the smallest thing in notebooks, was partly why Pym’s unmatched at the absurd minor-key social skirmish. Here’s one incident that went from the diary to No Fond Return Of Love.

Then there was this field study instigated by Hilary, described in a letter to a friend:

Hilary set to work the other evening compiling a list of all the people who had ‘worshipped’ at St Laurence’s since we came here that we could remember. We then analysed the circumstance of them leaving — if they had left — and came to the conclusion that they had been removed by Rome, Death and Umbrage. A good title for a book, don’t you think? Umbrage of course removed the greatest number.

Umbrage would.

***

A photo taken by Philip Larkin of, from left, Monica Jones; Hilary Pym Walton; and Barbara Pym

One regular correspondent and steady supplier of amusing minutiae was Philip Larkin. He first contacted her after the publication of No Fond Return Of Love, her sixth published novel, to ask if he could write “a review essay on her books.” This was in 1962; she was nearing 50, he 40.

His sister had introduced him to her books, and he was a fervent admirer. She agreed to the essay, and not long after he wrote:

I have just begun reading your corpus in earnest, pen in hand…. There are dozens of things I should like to ask, but it is probably better for me to put down what I think unprompted. I remember the tremendous trepidation and trembling with which I put my most cherished critical ideas to Mary McCarthy: had she intended, etc. She listened to the end and then said ‘No’, that was all. Moments with the Mighty.

Their letters back and forth to each other are a joy. They talked about writing, and they gossiped about their jobs and housekeeping arrangements. They were uniquely placed to appreciate all the different compartments of each other’s lives. She might write him about the Institute’s journal — “We have plenty of ‘problems’ with the next Africa — trying to avoid having two rather dull articles together…” and he would, as he made his rounds as University Librarian, look up the issue. In his letters, he might tell her about a new bedroom carpet he’d bought, or complain about the students or the academic posts he’d been offered: “The University of Wisconsin offers me a year as Writer in Residence, with lectures, creative writing seminars, and ‘informal coffee hours’ — could this be worse do you think?” There’s the pleasure, too, in seeing him refer to “Aubade” offhandedly as his “in-a-funk-about-death poem.”

At first they’re friendly but formal, then over time their letters relax. They become “Philip” and “Barbara” to each other — always an important benchmark in Pym world. They go on at such a comfortable pitter-patter it comes as a shock to come upon a letter where they’re arranging a meeting, at a hotel bar in Oxford, and planning how they’ll recognize each other and to realize that they’d never before met in person. Larkin: “I am tall and bald and heavily spectacled and deaf, but I can’t predict what I shall have on.” This sent 14 years after his first letter to her.

The main cheering thing about their correspondence, though, was its timing. It started right at the time she stopped being able to get published. From 1950 to 1962, she’d published six novels, all of them with Cape; these had been “well received” and done modestly well in sales. Her seventh, written in the same vein as the first six, was turned down, brusquely: “Dear Miss Pym — I feel that I must first warn you that this is a difficult letter to write.” Etc. No invitation to submit in the future.

Writing indignantly to a mutual friend, Larkin said: “If her publishers are correct, it is surprising that there was not someone at Cape prepared to invite Barbara Pym to lunch and say that while they had enjoyed her books in the past and hoped to do so in the future, this particular one needed revisions if it was to reach its potential value. It was the blank rejection, the implication that all she had previously written stood for nothing, that hurt.”

She sent the book, An Unsuitable Attachment, on to other publishers. No takers. It was the early 60s in London. Catch-22 and Ian Fleming were bestsellers. A novel about a female librarian who makes a trip with her church group to Rome must have seemed like some naïve obsolescent dodo wandering the scene. This wilderness period lasted 15 years. How dark those years must have been. She was getting older; she went through treatment for breast cancer, she suffered a freak stroke. Her first books went (mostly) out of print. She remained stoic, gently, bravely, philosophically amused. While in hospital: “I can’t make out whether the other ladies here are breastless (like Amazons?) or have other things the matter with them.”

During this interval she wrote a few other novels, even though she had little hope they’d ever be published. “Novel writing,” she noted, “is a kind of private pleasure, even if nothing comes of it in worldly terms.” Larkin’s letters — warmly admiring, astonishingly perceptive (he was her best critic in reading her drafts), rude on the subject of publishing house’ readers — must have been sustaining:

Yes, I read your books, in order, in succession, as I do from time to time, and once more found them heartening and entertaining — you know, there is never a dull page: one never feels ‘Oh, now I’ve got to get through this before it becomes interesting again — it’s interesting all the time.

When she wrote him, uncharacteristically down, “Here I am sixty-one (it looks worse spelled out in words) and only six novels published — no husband, no children,” he wrote back, “Didn’t J. Austen write six novels, and not have a husband or children?”

It was due partly to Larkin she was eventually published again, too. Asked by The Times Literary Supplement in 1977 to name the most underrated writer of the century, he named Barbara Pym. So did Lord David Cecil, which made her the only living writer on the list to get two votes. Interest in her stirred. With it Larkin was able to interest The TLS in his long-planned article about her work. She published Quartet In Autumn, one of her best (and most devastating) novels, which had been waiting — it was shortlisted for the Booker. Larkin was the chairman of the judging committee.

Writing to her about the prize night, Larkin says:

Wasn’t Bookernacht bewildering! I do hope you enjoyed it. Fancy meeting Maschler [from Cape] — more than I have. I never saw the table plan at all. I’m sure all sorts of famous people were there. A little man came up to me and said: ‘I’m Lennox Berkeley’, and I nearly said ‘I loved all the dances you arranged’, then remembered that was Busby Berkeley, and this chap was some sort of Kapelmeister.

(Not being particularly stoic, I cry like crazy at this letter and the buoying Jane Austen letter whenever I re-read them. The jubilation and nonsense of the second one! I loved all the dances you arranged.)

When Barbara Pym died, in 1980, of abdominal cancer, she had published eight books, and a ninth was ready for publication. She had experienced Bookernacht; a tide of good reviews; the Church Times had gratifyingly and hilariously reached out to her (her heroines are always puzzling and mulling over their copies of the paper); and she knew her books were being taught in universities in England and the U.S. After her death her sister donated her papers to the Bodleian, which seems the perfectly right place for them to be archived. In 1942, writing in her journal, she’d said: “This evening I was looking for a notebook in which to keep a record of dreams and I found this diary, this sentimental journal or whatever you (Gentle Reader in the Bodleian) like to call it.” She knew she’d land there.

Previously: How To Be A Monster: Life Lessons From Lord Byron

Carrie Frye is here and here. Top photo by Mayotte Magnus © The Barbara Pym Society.

Younger People Eat Differently

“They tend to travel in groups, eat late in the evening and can lend restaurants a cool cachet, attracting more patrons of all ages…. Restaurants say these diners not only are very demanding about the food, they want to know the story behind what’s on a plate and are lured by rarefied experiences. Often they want something seemingly elusive to brag about on Twitter and Instagram…. These consumers grew up immersed in restaurant TV shows and celebrity-chef culture. Attention to organic food and labeling that promotes where food comes from became mainstream during their childhoods.”

— You know what I haven’t seen yet about millennials? A story on how they take a shit. (It probably involves Facebook and expressing feelings about how no one else has ever taken a shit before them.) Other than that I think I’ve probably learned all that I need to.

Photo by thejanner

Beaver Camera-Shy

“The fisherman wanted his photo shot with a beaver. The beaver had other ideas: It attacked the 60-year-old man with razor-sharp teeth, slicing an artery and causing him to bleed to death.”

The Park Slope Food Coop Board Of Directors Race Is On And It Is Hot!

There are two positions open on the board of the lovely Park Slope Food Coop, that magical place in Brooklyn where neighbor turns against neighbor regarding issues such as boycotting Israeli food and, oh, anything else. But! There are four candidates for the board! Which one will not make the cut!? Here are some excerpts from their statements, which were, the Coop’s Linewaiter’s Gazette notes, printed “unedited.” [PDF here.] Let’s meet them!

• “My personal life reflects my dedication to the values of the Coop. As an avid bicyclist, commuting 30 miles a day year round, to and from my office in Queens, and as someone who loves to cook and bake, I too cherish the availability and taste of excellent food.”

• “I started going to the General Meetings about 11 years ago. Initially, I went for work slot credit and was surprised to discover that the meeting was small compared to the vast size of our membership and that the diversity which I saw while shopping at the Coop was not powerfully reflected in the meeting. I thought to myself, ‘Here is the decision-making body of the Coop and only a few members are making these decisions and even fewer people of color.’”

• “People I meet on my travels often ask me where in the world I would most like to live, since I have been fortunate enough to see so much of it. I can answer honestly in one word: Brooklyn.”

• “In my judgement what is needed for the Board of Director position is to interact with those in attendance at the meeting such the membership is able to draw the appropriate conclusions for themselves as to if it is wise to offer specific advice for acceptance. Should the membership choose to offer the advice much to the silent objection of the Board of Director, in knowing myself and the Coop, could I comment or ask a question to create an awareness that would have not otherwise occurred?”

Yes! Congratulations to three of the candidates, who are largely coherent. We hereby endorse Imani Q’ryn, who made the excellent point about lack of people of color in leadership roles, and also whichever one of the white ladies who makes sense. Maybe not the one who bikes 30 miles a day either, that seems nuts. Elections will take place at the general meeting June 25, 2013. SEE YOU THERE.