I Think I Solved The Mystery of Dua Lipa's Face

Can you check my math here?

Hey nerds. Summer school’s in session and I need you to look over this theorem I’ve been tinkering on.

First, pls watch the Dua Lipa “New Rules” video (it bangs).

You back? Amazing. Okay so I can’t be 100% certain, but I’m pretty sure 1 Dua Lipa = 1 Aubrey Plaza + 1 Ivanka Trump.

Take a peek:

Alexa, shuffle:

Siri, jumble them:

Was looking at the Ivankas triggering? They were definitely triggering to take screenshots of*. Sorry about that. And sorry in particular about the American flag one, but her neck was really having a moment re: that updo and unfortunately it was necessary to the comparison.

Anyway, I’m right, right? Dua Lipa = Ivanka Trump + Aubrey Plaza, facially?

Amazing.

____________________________

*Did you know that when you watch Ivanka Trump interviews on YouTube, the ad you’re served beforehand features Karlie Kloss building her own website using Wix?

Previously: Ron Livingston, Jake Johnson

Bethany Beach, Delaware, July 18, 2017

★★★★ The waves were of no particular color and they came in irregular but strong, some of them making compact tubes before they smashed and acquired the color of sand and foam. Boogie boarders threw themselves at them, standing upright only long enough to be knocked over. A blue blur of spray hung over the populated part of the beach. Dolphins showed their fins and then long stretches of their dark backs, moving north to south, not at all far beyond the people in the water. Ospreys too were coming close and low. One stooped toward the water, pulled up, then finished the dive and came up struggling with a fish. It headed off, laboring just above the swells, and then the sight of its progress was cut off by a huge wave rearing up, already glassy-tipped and inescapably breaking. Then there was nothing but the swirl of sand and water, in bright and directionless confusion before the bottom became the bottom again and the salty sky became up. The afternoon sun on the mini-golf course was sharp enough to raise doubt about the sunscreen. The children got in the way of each other’s putts and then in the way of each other till the five-year-old fell on an obstacle rock and got up scraped. On its way down the sun was still searingly hot on the deck. Swifts or swallows crisscrossed the sky as the light shone on the clouds from below.

Dispatches from the German Penis Beat

Deutschland über us.

When I was a junior in high school in the early nineties, I was mildly obsessed with the German exchange student, Christoph, a soft-spoken, ponytailed Blues Traveler fan who sat behind me in pre-calc. (Fine, I admit it: fellow Blues Traveler fan. Everybody in Oregon liked Blues Traveler in 1992, and that is a fact.)

One day, we were hanging out in the library, and Christoph sat looking perplexed as our friends embarked on a round of the Penis Game, which, if you’re not familiar with the oeuvre, is a sophisticated contest of derring-do and wits, in which participants take turns saying the word penis in an inappropriate setting — bar mitzvahs, assemblies, funerals — at escalating volume. The “winner” is he or she who bellows the word for the human biological male’s primary sex characteristic at the loudest register possible.

“Penis,” whispered my friend Les. “Hey Christoph,” I said. “How do you say penis in German?” “Schwanz,” he said. “Penis,” said my friend Ari at a normal volume. The librarian shushed him.

“SHVONTS?” I repeated. “Yes, that’s right.” I made him write it down. (Years later in Berlin, I would watch a dubbed version of Reservoir Dogs, where Tarantino’s infamous “Like a Virgin” monologue spoke of Schwanz auf Schwanz auf Schwanz auf Schwanz auf Schwanz.)

“So when you play the Penis Game in Germany, is it the Schwanz Game?”

“We don’t play the Penis Game in Germany.”

“PENIS!!!!!” (Winner: Les.)

I was still taking Spanish at this point, so Schwanz was the first German word I ever learned. (The second was the word for “jump,” springen, pronounced SHPRING-un. “Hey Christoph, how do you say ‘Jump! Jump!’ in German?” I was Christoph’s favorite.)

I have long insisted that an English edition of Kafka’s Metamorphosis (and an unfortunate affair with a Teutonophile later in high school) is the origin story of my lifelong obsession with the land of Wagner and Wurst — but now that I think about it, the truth is this: So taken was I at that moment, by what I assumed was Christoph’s extremely sophisticated and cosmopolitan attitude toward male genitalia, that I made a mental note to study German in college on the spot. (It was not until my junior year abroad, however, that I learned that Schwanz is slang for dick, and the technical term for penis is…Penis, pronounced PAY-nuss.)

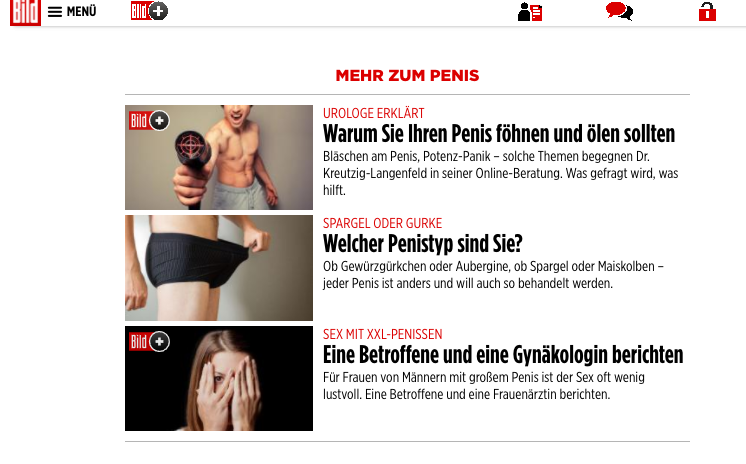

It’s twenty-five years later, and I can’t speak for Christoph, but the rest of his Landsleute seem as blasé as ever about, well, the preferred organ for das Blasen. Even the prurient, ridiculous BILD newspaper, which traffics in boob shots and sensationalism (“How’s it going with This 80-year-old Grandpa-Dad?”), has little more than a shrug for the latest bombshell out of the porno-sphere: the adult site CamSoda’s forthcoming login via “dick-ometrics,” i.e. the dick-pic as password. (No word yet on what the site’s hordes of non-phallused users will do. I’ll keep you posted.)

Sure, BILD’s blurb has a passable German version of a pun about “getting membership with your member” — mit Glied Mitglied werden, one of the better demonstrations of German’s close relationship with English. But otherwise, even the BILD staff doesn’t seem particularly scandalized.

Instead, the German penis beat seems to be just another news category in the country’s most-read publication, evident in the CamSoda piece’s interstitial ad, which boasts MORE IN PENIS NEWS, and links to a larger array of matter-of-fact schlong journalism than even BILD should reasonably be expected to purvey. (Speaking of which. The German word Schlange, pronounced SCHLONG-uh, means both “snake” and “queue,” and my long-suffering freshman German prof’s description of a long line — eine lange Schlange — caused my entire class of Americans to be incapacitated with Penis Game-esque giggles for the better part of a week.)

The German relationship to the human penis is paradoxical, just like the German relationship to, say, order — to be ordentlich (OAR-dun-lish) is, along with being pünktlich (POONKT-lich, or punctual), one of the culture’s most prized qualities, and yet the coat-check Schlange after any show in the country is not a queue so much as a mandatory clothed orgy.

Anyway, speaking of orgies: Your average German is far more likely to see a stranger’s penis in regular day-to-day life — on TV, where soft-core pornography has played after 10 p.m. on free channels for decades; in a nonsexual capacity on the FKK beach — and they are, as Christoph explained back in the day, less likely to make a big squeamish giggling deal out of it. (Compare this to the prized ideal of the Evangelical American virgin bride who, until her wedding night, has never seen a human penis once.)

And yet (the Fundamentalists are gonna crow when they find this out): The demystified dong doesn’t seem to correlate with a particularly prodigious or un-prodigious desire for doin’ it — indeed, the average age of German virginity loss, 16.2, is more or less the same as our own, of 17.1. (I guess those purity balls really do work — eleven extra months of chastity!)

When I was a German professor, it was always my goal to impart not just grammar and vocabulary, but intercultural understanding, by which I mean making my students deeply uncomfortable and then hoping they would be remotely curious as to the origins of that discomfort. This I accomplished almost entirely with viewings of the repertoire of legendary German Schwanz-artiste and sometime filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder. (“WARNING,” I’d write on page eleven of my fifty-page syllabus, “THIS FILM CONTAINS FULL-FRONTAL MALE NUDITY. PLEASE BE CHILL ABOUT IT.”)

As a proud member of the Young People’s Corruption Brigade, it was not just my vocation, but my sacred duty to nudge straight-laced Ohioans in the general direction of slightly less uptight fetishization of the human bathing-suit area. Sure, most of my students were already too old for my pernicious influence to contribute to lowering the dowdy U.S. virginity-loss age, so we could finally beat Germans at something besides a Best Inane Small Talk contest. But perhaps, at least, my university’s German majors could attend their own graduation with slightly less of an inclination to scream SCHWANZ during the speeches.

Indian Wells, "It's Where The World Ends"

This is where we are.

If you had told me back in 1994 that the day would come where I would pray that the only thing on the news was O.J. Simpson I would be like, “I cannot imagine what horrible things would have to be happening in the world for that to be true.” But there’s no way I would have believed you if you told me what those things were, because it would be impossible to conceive of a world in which we would not only allow such absurdity occur, but continue to such an extent that eventually we would become used to it. And yet here we are, hoping only that tomorrow is all Juice. You don’t have to laugh but there aren’t many other options, really. Here’s music. Enjoy.

Bethany Beach, Delaware, and Environs, July 17, 2017

★★★ The air conditioning, running cold overnight due to a misunderstanding about the number of thermostats, precipitated a thick film of condensation on the outside of the windows. The swimming things on the clothesline had given up their old dampness to the air and were now acquiring new dampness from it. The morning was cloudy enough to divert the usual beach time to errands and the go-kart track instead. Inland, where the clouds had shape, the ten-year-old spotted a rectangular space among them. The midday sun cast half-weight shadows on the Jr. Stock track, and the slow fade-in continued through the afternoon. Grackles clacked at one another from the willow tree and the chimney top. The five-year-old convinced his three-year-old cousin to use the sprayer on the hose, till the saturated lawn glittered. The ever-clearer sun held off the arrival of evening, stretching out in a coda more gorgeous than the rest of the day deserved, while huge mounds of cumulus formed off to sea and the fuzzier, lower clouds in the west made their slow progression from ivory to purple.

How To Come Out On Camera

A good coming-out scene acknowledges that the first time is just that — the first of many.

Coming out is a boundless, never-ending endeavor. You come out on the government forms. You come out at the grocery store. You come out at the office mixer. You come out on the app(s). But across film and television, whenever you find a queer character, coming out, in its various incarnations, is as implied as opening and closing credits. A little like how in the dinosaur movies there is always the scene where the biggest dinosaur faces off with an equally big dinosaur. Or how, in the thriller, eventually someone jumps out of a window. Or how if Jackie Chan is in a movie, even if he’s five decades older than everyone else, he is almost certainly going to fuck someone up. If you are watching something with LGBTQ+ folks on your digital screen or whatever then buckle up because someone, somehow, is going to come out.

I didn’t really grow up with (out) queer folks in my life. For the longest times the only (out) homosexuals I knew were Jamie and Ste from Beautiful Thing. I caught the film in the early-aughts, in this hotel in Costa Rica, when I would’ve been nearing the end of junior high. And the only thing more perfect than the heft of its gayness was my not knowing that about that gayness until this happened:

Did you see that? Word? Please watch it again.

There are several things that make this a perfect scene: Jamie’s tentative confidence as he caresses Ste’s shoulder’s. His mother’s interrupting the boys’ momentum, which actually inadvertently accelerates it. The awkwardness with which Ste eventually orients himself to Jamie’s body, and then the un-glorified fact of their intercourse, and then the dawning across Ste’s face the next morning, when he realizes what they’ve just done.

That shit is P-E-R-F-E-C-T. Twelve out of ten. When Ste says, “Do you think I’m queer,” and Jamie says, “It doesn’t matter what I think,” it puts me out of my chair or the sofa or my desk every time. And when my boss or my students or my boyfriend asks what’s wrong, who has finally been fired, I show them that scene and wait for their euphoria too.

Other things happen in the film. There is gossip and deception. The boys become more comfortable with their respective sexualities. But none of that much mattered the first time I watched it. And it didn’t even matter that my notions of queer visibility were being formed by two white boys from England, as opposed to any of the black or brown faces that made up my immediate vicinity, because, at the end of the day, I’d never seen anyone come out to themselves (or anyone else) before.

I felt like how toddlers feel when they tread water for the first time. Or when the cat finally lets you pet her and you realize maybe things are OK. Or when you’re at the taqueria and you don’t know if the card’s going to clear, but it does, and for a while you and the register guy are just standing there, like, “DUDE.”

Every coming-out scene is perfect. They’re all perfect in different ways. Which is a tremendously stupefying thing to hear, let alone say. But even if each of them is a tiny miracle, there are certainly a few different types, and because we’re really all just primates relying on ultimately reductive organization schemes, here are a handful (!) of the different ways characters come out on camera:

The Culminating Plot Point:

This is the most common one. It’s the first instance you think of. Many adult humans who spent time on Earth in 2005 have heard some variation of Brokeback Mountain’s “I wish I knew how to quit you”:

Coming out — to your parents, or your peers, or your crush — is such a pivotal moment in one’s life, that screenwriters naturally take it upon themselves to make that event the focal point of their thing. Sometimes, the film’s momentum leads up to that final concession. Sometimes, the coming-out is what spurs the momentum of the film:

Sometimes, it is a long-held declaration of love. Sometimes (most of the time) there’s tears and gasping and sadness, and then the pause where the teller ultimately waits for a reaction from the told.

It isn’t lazy scene, per se, since a life can very literally be reimagined by that one event (mine was) but it also might not be the most illuminating scene you will ever watch in your life (until it is, and the result is an unattainable standard that ruins you and your expectations re: intimacy FOREVER):

The Comedic Epiphany:

The inherent perfection of these scenes aside, this one’s usually pretty rough. It banks on masculine/feminine stereotypes, and it really only works if the viewer believes that queer folks can only be some kind of way:

The coming out matters, but it’s a deflection for some larger bit where, like, this character is queer, and now he’s stuck in a cave with four other dudes; or coming out is a catalyst to a larger joke about a crocodile stuck in a car trunk; or some idiot man drunkenly mistakes his cousin for his partner so now he’s out or whatever.

Sometimes, there are bonus points for this scene’s illuminating something a little less daft: like how not everyone comes out the same way, or how you’re not anyone’s clock to come out (besides yours). And sometimes, even the not-great ones at least attempt to redeem themselves later on.

The Spent-The-Whole-Episode-Talking-About-Something-Else-In-Order-to-Avoid Coming-Out-Before-Ultimately-Coming-Out:

Every now and again the coming-out will be veiled under some sort of quasi-comedic misunderstanding. Like, “in order to show you that I’m not gay I’m going to do this that and the other and we’re all going to laugh until I come out”:

Living that scene indubitably sucks. It is actually the worst thing. There’s really no metaphor to encapsulate it, aside from maybe hanging out in the fourth layer of Hell for a bit. And then someone tells you that it’s time to go now, so you pack your bags and everything but really they don’t mean that it’s time to leave. They’re just taking you to the fifth layer. And then you just do that for the rest of your life.

But condense an arc to twenty-eight minutes and sometimes it’s funny. Television is wild.

The Meal:

Everyone eats. Don’t you love food? It is fucking delicious. So the dinner table or the diner is as good a place as any to come out on camera. Bonus points for constructing the entirety of your episode/film around a conjugal meal, with an entirely non-white cast, whereby changing the gravitational flow of who exactly gets to have those conversations in our well-funded narratives:

The Mirror:

This scene is less of a scene per se than a prolonged movement — a character (x) has come into contact with an individual (y) representing the person that they themselves would like to become. I guess if you were in grad school or whatever you’d call x and y foils, but they aren’t exactly opposites every time:

Sometimes it’s their sameness that makes the interaction poignant:

Sometimes they’re so (supposedly) different that crossing the (supposed) distance between them is the point of the scene:

A disproportionate number of these scenes take place in schools, where it’s usually at least a little more difficult to run away from your problems. Or the character’s gone on a trip to Oaxaca or Lagos or Prague, cities where interesting things have been known to happen. And more often than not, this scene occurs when an old friend reappears in one’s life and it turns out that they’re gay:

Then the friends have a choice to make. A choice that generally ends in casual, but meticulously choreographed, sex.

The “Did They Just Come Out?”:

An alternate title for this one could be the “I Read Somewhere Before I Saw The Film That They Were Going to Come Out and I’m Not Sure If They Did”? Or “Is That The Scene Where They Told Us They’re Queer”? Or “What?”:

You will know when you see it because you will not know what you’ve just seen.

The Unstated but Meticulously Plotted Development:

There are people in this life that think you and I are inherently knowable, and that by watching us long enough they’ll figure out who we are and what we think. That’s a lesson you encounter forever until you learn it, but in the meantime this scene is for them:

The film/episode strategically litters its character’s interactions with “clues”. Like, if they spend enough time on-screen with this individual of the same same/opposite/undefined sex, then surely the audience will come to this conclusion! But also maybe they won’t! And we’re not going to tell you! My first serious relationship was a variation of that scene. It is as maddening to live as it is to watch, and the payoff is generally dubious at best (“Aha!”).

The god-child of this scene is the “Obviously Queer Minor Character the Director Refuses to Give an Entire Arc is Regrettably Attracted to a Straight Character and Eventually Tells Them So”. Which, while also perfect (!), can be equally distressing:

The One Day All of A Sudden Scene:

This scene accounts for the fact that coming out, on any given day, is a pretty big fucking deal. But it mostly acknowledges that self-discovery is never a closed event. It cannot be planned. There is no beacon. There is no Bat Signal. But, sometimes, things just happen and you get a little closer to you are:

This scene is optimal, and you hardly ever see it. When you do, it’s that something that you remember forever:

A good coming-out scene acknowledges that the first time is just that — the first of many. It is a process you’ll repeat until you die. And every time it doesn’t end egregiously is a miracle. Every time it ends and starts again is a miracle:

A good coming-out scene is a miracle. Queer folks are miracles. Go make more coming out scenes.

Go Independent Or Go Home

How leaving big publishing for a small press made me a better writer and happier person

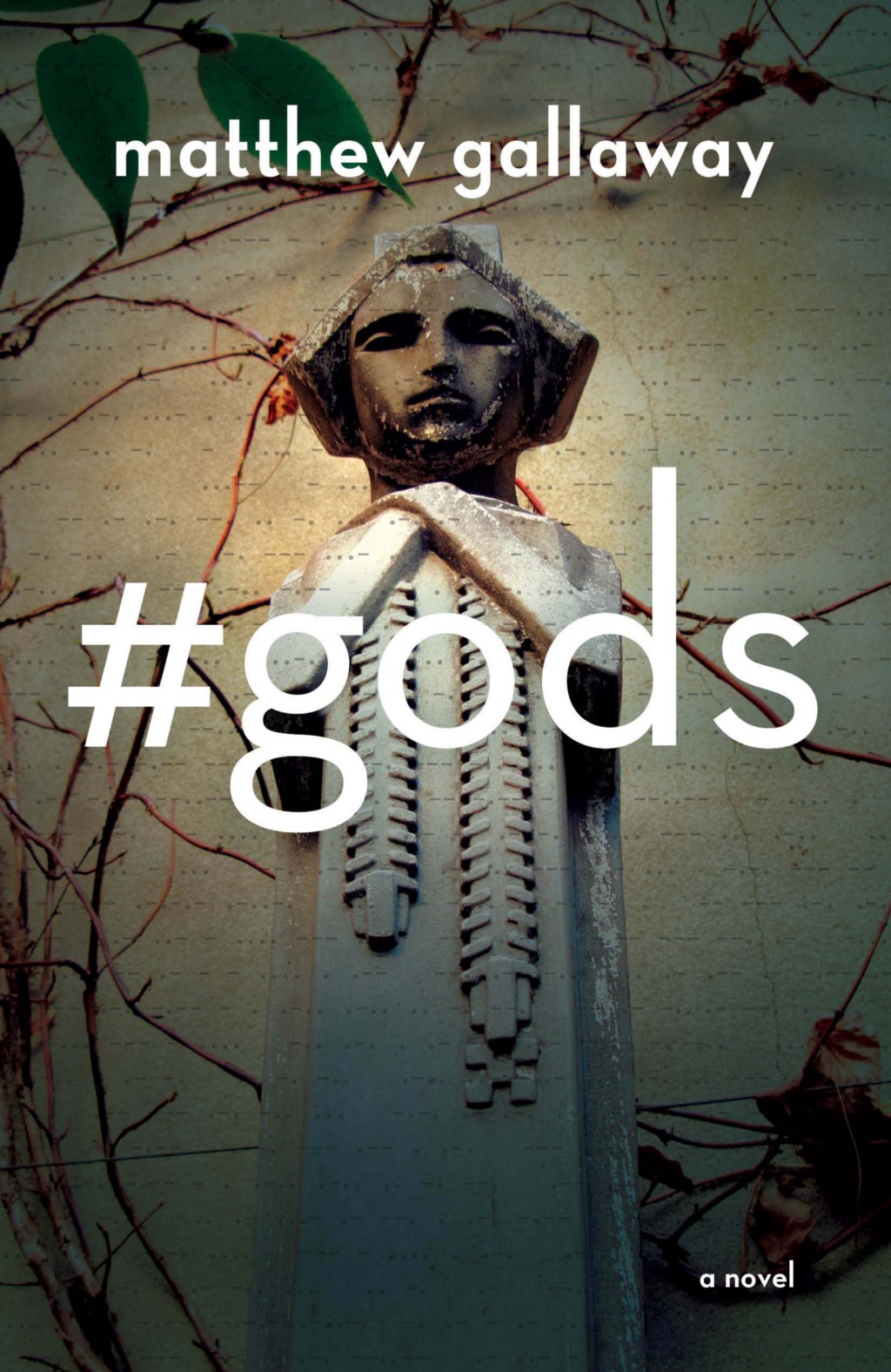

Today, my second novel is being published by an independent press based in San Francisco. It’s technically a “soft launch,” meaning the publisher — Fiction Advocate — will start shipping copies to anyone who orders direct, with the official/Amazon pub date pushed back a month, to August 22. (The book also costs $5.00 more on Amazon and won’t include shipping and handling.) Economics drive this strategy: with the unit cost around $5.50, and Amazon charging something on the order of $18.50 to sell a $25.00 book, it leaves the publisher with about $1.00 profit per copy on Amazon sales. For direct orders, by contrast, the publisher keeps $20.00 minus the unit cost and two or three dollars for shipping, which is included. My royalty — 10 percent, which is based on net profit (the money the publisher receives for the book) — is $2.00 per copy on a $20.00 direct sale versus $0.10 or $0.15 for an Amazon sale.

The goal: If the publisher — which pays no author advances, salaries, or office rent — can sell a few hundred copies direct and a few hundred more through their independent, non-gouging, non-Amazon distributor, they will make back their costs and some extra, which they’ll put into their next project. (My royalties should pay for a few nice dinners in New York City?) So far, over three years of operation, their growth has been slow but steady; mine is one of a handful of books they plan to publish in the next year or so.

The five remaining major trade houses in the United States — aka Big Publishing (click here for insane chart) — do not have this flexibility; to show even modest gains, they must publish increasing numbers of books. Following the decimation of brick-and-mortar bookstores, they rely on Amazon to sell enough copies to cover author advances, office space, employee salaries, and whatever else they spend money on. While their margins are higher than an independent on a per-book basis, thanks to bigger print runs and a (somewhat) better take from Amazon — not to mention far greater sales numbers for (some) titles — their long-term prospects are increasingly murky.

A few things are happening. The first is that we don’t read as many books as we used to. You know this is true. We watch television until it hurts and then we watch even more television. We spend hours crying silent tears of agony as we scroll through our Facebook and Twitter feeds. If you spend your days making a living on a computer screen, the idea of picking up a book can feel like punishment. Words have never been more exhausting, which is bad news if you want to sell thousands of books.

Second, as with the music business, books have become “nichier,” which makes marketing a trickier proposition. Genuine blockbusters are increasingly rare, and books with sales of a few thousand copies appear on bestseller lists. Third, book-making technology (again, like music), has become cheaper and more accessible, producing books that look and feel as good as, if not better, than those made by Big Publishing.

Facing all the above and strapped with shrinking profits, clunky legacy systems too expensive to replace or upgrade, and bloated management hierarchies (seriously, did you look at that chart?), Big Publishers have tried to maintain bottom-line revenue by cutting costs through consolidation, layoffs, and greater use of freelancing and outsourcing. The predictable, undeniable result is that their books are shoddier and their staffs — particularly at the ground level, where most of the important work of publishing gets done — are overworked and underpaid. Extinction for these publishers may not be imminent, but it’s inevitable.

Have you seen “Colony?” It’s a television show on USA about what happens to Earth in the wake of an alien invasion. The aliens (never shown, except for their killer drones) have surrounded L.A. with a gigantic wall and installed a puppet government. While most of the population scrapes by in urban squalor, officials and their families live in a “Green Zone,” a manicured, gated community that offers its inhabitants all manner of pre-invasion amenities. While superficially calm, life in the Green Zone, thanks to insurgents who sneak on and off the premises to commit acts of violence, is increasingly chaotic. If the officials can’t control “the insurgency” and — by extension — the larger population, the aliens may decide to kill everyone and turn the entire city into a parking lot.

I’m not here to recommend the show, which is at best conceptually engaging, but too often slides into tedious melodrama about heterosexual family life on the run (and bad wigs). It does, however, offer an almost perfect metaphor for the book-publishing industry. The Green Zone is that precarious landscape occupied by Big Publishing, and especially senior management and their police force (literary agents) who are still well compensated to usher in and manage the labor (authors). The alien overlord is Amazon (drones), which not only takes a big percentage of a book’s profits, but also dictates the operations of its colony.

Big Publishing is too tethered to Green Zone amenities to make any effort to leave or revolt; instead, in a state of collective denial, they try to please their overlords with “guaranteed revenue” (celebrity memoirs! sequels!), a wellspring that, however deep, can provide for only so long. Increasingly risk averse, they are incapable of publishing books that reflect the growing diversity of the population (in pretty much whatever way you want to define it) and make survival for “midlist” writers more and more difficult. (This has been happening for decades.)

That Big Publishing remains conservative and homogeneous — and viewed with increasing ambivalence and disdain by the larger population — should not be surprising or contentious; axiomatic in antitrust law is the idea that a reduction in market participants, whether a result of competition, attrition, or consolidation, correlates with a reduction in consumer choice. We’ve seen this across any number of industries in our society, including airlines, automobiles, banks, pharmaceuticals, newspapers, and commercial publishing, where somehow Penguin Random House isn’t the punchline to a joke.

Then there’s Amazon. If you talk to your overworked/underpaid friends who work in the trenches of Big Publishing, you’ll be keenly aware that no decision — from “content” to book covers to publication schedules to sales/marketing strategies — gets made without considering the actual or looming impact of the alien overlord/distributor. If Amazon is “unhappy” about anything, or if the perception of unhappiness is wielded like a dictatorial cudgel, the publisher will scurry to find a solution. The message — and the reality — from Amazon is: Make Us Happy or Die Trying.

Whether and how the demise of Big Publishing “matters” is a more subjective question. My own experience with Big Publishing is mixed. As a reader, my bookshelves (real and virtual) have a mix of titles by Big Publishing and independents. As a writer, I published my first novel in 2010 with Crown, an imprint of Random House. Based on BookScan, it has probably to date sold between 5000–6000 copies in hardback, paperback, and Kindle/ebook formats. (Exact numbers are very difficult to come by, and I’ve never seen a royalty statement.)

Like every author who gets signed by Big Publishing, I had an agent. In 2007, Crown bought the manuscript, paying out an advance in the very low (but still very high) “six figures,” fifteen percent of which went to my agent, and the rest to yours truly in three installments: signing, submission, and publication. (Around forty percent went to the IRS, also.) Though an outlandish amount of money to pay for a debut novel by someone best known for posting photographs of “hot gay statues” on my blog, Big Publishing still regularly/perplexingly doles out far more for debut novelists they hope will make it “big,” despite the fact that almost nobody ever does.

After this first novel finally published, to some acclaim and some derision, I was still excited enough that, when, two years later, Crown decided not to exercise their option on a second novel, I also felt like a failure. There were many reasons why the relationship fell apart. Sales — though not horrible for a first “literary” novel — were undoubtedly a factor, although nobody ever said so. Also problematic (although again, nobody ever said it, at least in so many words) was the subject matter of the book/s. My first novel was definitely “a risk” given that it was not only “gay” in thematic and sexually explicit senses, but also featured a primary character who was HIV positive, as well as opera, incest, a magic longevity potion, and — yes — a dying cat.

While my second novel could also be described without gay-pigeonholing it — specifically, it deals with faith or “faith,” or what we’re supposed to “believe in” if we don’t buy into traditional monotheistic religions/capitalism but find atheism too depressing — it’s also more “stridently gay” than the first one. There’s an all-gay, underground operation whose members are trying to contact a race of immortal beings/gods who may or may not be returning to the society they once ruled. There’s a subplot involving a semi-professional lesbian bowling league.

I mean, it’s obviously aWeSOmE and you should read it, but it would have been much more difficult to “market around” what the book is actually about, especially back in 2013, when people had a harder time admitting that our society is a train wreck for pretty much anyone who’s not rich, straight, white, and male. The plot also did not — as my editor put it in the coded bigotry of marketing — appeal to Crown’s “core demographic.” At a meeting with the editor and a new publisher, who had been installed during a regime change, the publisher expressed concern about avoiding a “sophomore slump” like (her examples) Zadie Smith or Curtis Sittenfeld. I heard these words and stared out the glass windows at the glittering, midtown skyline: somehow, I had ended up in a satirical movie about Big Publishing.

We went back and forth for about eighteen months (note: don’t ever do this without a contract), as I attempted to address vague directives from the editor: “Can we do something to make [this character] more compelling?” I finally turned in a “major rewrite,” which was followed by six months of radio silence: Crown wasn’t saying yes, but they also refused to say no (and never did, putting me into a kind of Big Publishing purgatory). I finally admitted that I needed to escape. Knowing my agent’s hands were tied by Crown’s refusal to commit/not commit, and not wanting to “sneak around” with other agents, I left him. I went through the motions of querying a few others, but it quickly became apparent that my days in the Green Zone were over. As one agent put it to me, “You’re not even a debut novelist anymore.”

Time passed and the world did not end. I stopped worrying about a “career” writing novels. I don’t need a career: I already have one that (thank God) has nothing to do with writing fiction. For me, writing is an avocation on the order of gardening or making paper airplanes. I write because it offers the chance to escape for a few hours each week into a dream world of my own making. I would love to have another big, fat advance (who wouldn’t), but I’m better suited to an independent. For small presses, existence is not divorced from the reality of Amazon, but — as my publisher has done — they can afford to take risks that their oligopolistic peers will not. They are the insurgents.

In my case, with no agent or “representation,” I sent the manuscript to the publishing director, who I knew in an around-the-office and (later) Facebook kind of way from a previous job (in academic publishing). After he moved to San Francisco and — with some friends — started Fiction Advocate, I bought a few of their books and was impressed: with each new title, they seemed to be getting more polished (no surprise, given that they all have experience in traditional publishing). There are hundreds and possibly thousands of small publishers around the country; reading their books is the best way to get to know them.

The publisher liked my new manuscript and extended me an offer; we negotiated a contract in two very low-key e-mail exchanges. The editing and production processes were more “collaborative.” My publisher didn’t ask for edits to appease an imaginary book club. He didn’t roll his eyes when I suggested using one of my photographs for the book’s cover. He also didn’t take three years to publish the book. The process was still “professional” — there was a copyeditor and a designer and proofreader — but was a lot more fun. Sales figures are still TBD, but with lower expectations, there’s less pressure. I’m trying not to be too annoying on Facebook and Twitter, but I’m doing what I can to promote the book. Like any writer, I want people to read.

At the same time, I’ve learned to think about publishing a book — any book — as something like winning a gold medal . . . in archery. Put it in your drawer, take it out to admire once in a while, and get back to the rest of your life. If things unravel with a publisher or an agent, don’t worry too much. If it makes you happy, keep writing. Or don’t. Nobody cares! And if, like me, you’re lucky enough to find a new publisher as a non-debut novelist, even if it’s a very small one that can’t afford to pay you ten cents for the manuscript, remember to be very grateful, because they’re demonstrating a kind of faith and resistance you once thought was lost.

Matthew Gallaway’s new novel #gods can be ordered here.

Pumpkin Spice Politics

Bumble, The Skimm, and branding your audience

“Always be branded at all times,” said Bumble founder, Whitney Wolfe, sitting in front of a wall that read “Bee yourself, honey!” It was the second weekend of The Hive, Bumble’s pop-up dating and networking hub on Mercer Street. Since its launch in 2014, Bumble has made a name for itself as arguably the least creepy dating app. Wolfe was a co-founder at Tinder, but was ousted after a breakup with fellow co-founder and noted dipshit, Justin Mateen, who proceeded to send her a series of threatening text messages. She filed a lawsuit accusing Mateen and CEO Sean Rad of sexual discrimination and harassment, settled for $1 million, and Bumble was launched as a corrective. By February of 2017 it had over 12.5 million users. More recently, Bumble has expanded beyond romance and launched a sort of friend-dating counterpart, Bumble BFFs. The Hive was the latest installment in Wolfe’s planned expansion, and a test site for the app’s networking iteration, Bumble Bizz, which is set to launch this Fall.

Were Crazy Craving, the old Honeycomb cereal mascot, to come into money and open a Drybar, it would look like The Hive. The walls were divided hexagonally, with screens in the honeycomb sections displaying a rotating collection of inspirational quotes like, “Be the CEO your parents wanted you to marry,” and “No one is you and that is your power.” Everything was yellow and white.

It was nine o’clock in the morning, but there were a lot of cold-shoulder tops and TV hair. The lighting was great, but the overall effect of The Hive made everyone look both wealthy and slightly jaundiced. I was there for Wolfe’s Q&A with Danielle Weisberg and Carly Zakin, cofounders of The Skimm, a political newsletter with over 4 million subscribers that, depending on who you ask, is either dynamic and buzzy or puerile and infantilizing. “This is such an incredible space,” said Weisberg.

According to Weisberg, she and Zakin started The Skimm because they saw a void. “We’ve loved news our whole lives. A lot of our early investors have called us ‘disruptors with love.’ We love news, [but] we saw that our friends just didn’t have time to read the news all day long. They’re real people, they’re smart, they knew everything about their industries, they’re curious, but they just didn’t have the time.” This is a party line. They told Business Insider essentially the same thing in 2015, saying that The Skimm was the newsletter for your “smart friend.”

The advice delivered during the Q&A was essentially useless — there was a lot of discussion about being “authentic,” not “plugging things in,” and “culture carrying” — the odd, vaguely fungal language of corporate feminism. “Everyone has to be a culture carrier,” Weisberg said. Wolfe nodded, vigorously, mouthing “YES.” Weisberg and Zakin both emphasized the importance of “the hustle.” When they started The Skimm, Zakin explained, “we shared an apartment.”

“In our time it is broadly true that political writing is bad writing,” George Orwell wrote seventy-one years ago. Mercifully, he did not live to see The Skimm, which Christina Cauterucci called “the Ivanka Trump of Newsletters,” writing for Slate in May:

Every blurb is painstakingly neutered of political slant or analysis and boring (read: important) stories are loaded with conspicuous snark about how uninteresting news can be. “Don’t fall asleep,” the newsletter warned of a paragraph on Trump’s plan to cut the corporate tax rate last month. “You’re still hearing a lot about Michael Flynn. Right…who’s he again?” another entry quipped, as if women move through their days osmosing names here and there, but never turning their attention away from their Birchboxes long enough to hear the end of the sentence.

the skimm has brain damage

The newsletter has been defended by Foster Kamer at Mashable and Kaitlin Ugolik at Columbia Journalism Review. “The Skimm isn’t for people who work in media,” wrote Kamer. “The Skimm is for people who don’t know what an RSS feed is and don’t care.” Ugolik admits that The Skimm has released no demographic information aside from the fact that 80 percent of its readers are women, but insists that dismissing the newsletter,

plays into claims of elitism that have lost us the trust of much of the American public. Since the election, journalists have been doing a lot of soul searching, and much has been written about how reporters and editors need to work harder to connect with swaths of the country they’ve long ignored, especially the rural poor. That isn’t necessarily The Skimm’s demographic…But the newsletter is reaching out to a group, millennial women, that is underserved in other ways, regularly underestimated and written off at times as entitled and uninterested.

Since the election, the media has spent a lot of time self-flagellating over operating “in a bubble” and being out of touch with the American public (cf. HuffPost embarking on a seven-week bus tour in order to connect with small-town America.) Kamer and Ugolik both seem to be under the impression that criticizing The Skimm is indicative of the kind of elitism that handed Trump the presidency. They both mention that The Skimm links out to accurate sources — but accurate sourcing (even in 2017) is literally the lowest bar for reporting. It delivers the news in language that’s colloquial and (debatably) funny, but that is…blogging. The Skimm did not invent blogging, it’s just a particularly bad example of it.

In their Bumble Q&A, Weisberg and Zakin specifically said that when they were starting out they would work out of Starbucks wearing Skimm shirts, leave flyers in Equinox, do college campus tours and stuff flyers under dorm room doors. They were targeting college-educated women with disposable income. I dropped out of college when the recession hit and I didn’t hear about The Skimm until I went back and saw my classmates reading it.

I took an informal poll of my friends — who do not work in media and do not have four-year degrees — and none of them had ever heard it. “What the fuck are those headlines?” said Rebecca Hillman, reading an excerpt that began, “What to say when your friend starts hanging out with your ex…Cutting ties. Yesterday, the Trump administration said it’s cutting financial ties with a Chinese bank that allegedly supports North Korea.” Hillman, 25, is a bookseller at the Strand. “Is this a real website?”

Ugolik understands that working-class women aren’t the target demographic, but still claims that “we as journalists haven’t yet seemed to grasp…that to reach more people — whether in a factory in Kentucky or at a cocktail party in Manhattan — our approach may need to change.” She’s right, the approach needs to change. But if anyone is “regularly underestimat[ing]” these readers as Ugolik said, it’s the newsletter itself — which simplifies current events to such an extent that they lose all meaning.

Two of The Skimm’s main backers are venture capital firms RRE Ventures and Greycroft Partners, both of whom have ties to Pete Peterson’s “Fix the Debt” Campaign, an astroturf movement active during Obama’s second term that was essentially trying to slash Medicaid and Social Security benefits under the guise of balancing the budget. The Skimm hasn’t promoted anything along those lines, but it does seem dedicated to keeping its readers apolitically informed in a way that’s troubling, given its funding.

The media is elitist, the media has a blind spot, fine — but the problems of “Real America,” shouldn’t be used as a stand-in for whatever you, personally, are angry about at the moment. The defense of The Skimm manages to conflate legitimately disenfranchised women with a vision of “The Basic Bitch,” that verges on parody — women so wealthy they barely have to care about politics. The Skimm ultimately isn’t really about politics, it’s about a brand. Weisberg and Zakin are planning expansions into video, a book club, and a lifestyle brand.

Far from being underserved, their audience is one advertisers target most heavily. Both Kamer and Ugolik equate criticism of The Skimm with criticism of its readers — a line of defense Gwyneth Paltrow used recently to defend her questionable doctors under the guise of defending Goop acolytes. “When they go low, we go high,” she tweeted out linking to an article that read “These women are not hypochondriacs, and they should not be dismissed or marginalized.”

Not every group is equally marginalized and not all criticism is elitist. There is a long history of women’s media treating women as if they’re idiots, and any defense of The Skimm essentially accepts that as a necessary evil. Although, to be fair, especially if you are an educated, adult woman — I mean, yeah, you can do better than The Skimm, and maybe you deserve a certain amount of opprobrium. “If you went to Vassar,” said Mandy Rodriguez, when I showed her Kamer and Ugolik’s articles — Rodriguez is thirty, did not go to college, and works primarily as a caterer — “and I’m serving your food, and I think you’re an idiot, how does that make me an elitist?”

Rebecca McCarthy is on Twitter

Laibach, "Vor Sonnen-Aufgang"

Is summer over?

“After the 4th of July,” my grandmother used to say, “summer is over.” Maybe yours did too: Any time I have related this anecdote at least one person in the group has said, “So did mine!” If I’ve learned anything it’s that grandmas love to remind you that summer is brief and its end ever approaches. The good news is, thanks to our inability to do anything about our changing climate, warm weather now lasts well into November here in New York City, so, in that sense, summer has a ways to go yet. But in all the official senses, and what with our already being closer to Labor Day than we are to Memorial Day, summer is in the autumn of its years. (Haha, get it? Hmm, does that phrase even mean anything to people anymore? No? Just the elderly? Ugh.) Pretty soon you’ll be in “summer is over and I wasted it” mode, and we all know how that goes. Try to appreciate it while you can, because it’s not going to be around that much longer. Anyway, here’s music. Enjoy.