Are You Useful to Anyone?

Are You Useful to Anyone?

Pitchfork Reviews Reviews was a Tumblr that launched in 2010. It, as one might expect, reviewed Pitchfork album reviews in a piercingly strange and touching voice — flat, declarative, obsessive, a bit breathless — that made it wildly compelling. But Pitchfork Reviews Reviews was only partly about Pitchfork reviews. The true subject of the blog was the anonymous young man who wrote it — his insecurities, his fears, and his triumphs of experience and understanding as he made his way through the various milieus of New York. It was weirdly elegant, tender and funny because of the author’s willingness to share uncomfortable details about his own life.

The deceptively banal confessional tone had a charm uncannily like that of the Nobel-bound Norwegian novelist, Karl Ove Knausgaard. And like Knausgaard, too, once in a while, the author of Pitchfork Reviews Reviews would really spill, and it was mesmerizing.

One year in middle school, I saw my friend Doug’s [gym class] card and it said 90 lbs and my card said 180 lbs and I wanted to tell him I weighed as much as two hims, and laugh, but obviously I didn’t because it was too sad to laugh about and I didn’t say anything.

So every day on the walk to school I’d get a $1.59 bag of Dipsy Doodles (which was a huge bag) and a Starbucks bottled Frappucino to supplement my lunch, which was like a chicken parmesan sandwich or cheeseburger and french fries and a soda, and my parents didn’t keep any good-tasting food in the house so sometimes I’d get candy from the vending machine and hide it in my bag and eat it secretly before or after dinner or before bed. One time I heard my mom crying and telling my dad that she didn’t know what to do to help me, and I used to look in the mirror and think of what I would do or give away to be able to lose weight, like I would think to myself that I would literally amputate one of my legs to make the rest of my body thinner and other stuff like that, or I wished I was too poor to be able eat that much, honestly.

The author, whose name is David Shapiro, grew up, lost weight, and wrote a novel of rare quality called You’re Not Much Use to Anyone. It’s not an “entertaining” book, per se — but it’s a fascinating one. It is virtually plotless, and its protagonist, David, who becomes Internet-famous for writing a blog called Pitchfork Reviews Reviews, exits the novel in a condition very nearly as clueless as the one we found him in at the beginning. Publicity materials for the book assure us that the David of the book is not the same as the real David, but that is as obvious as can be: The David of the book is not always very honest, while the David who wrote it is brutally so.

David is an only child, a dutiful and loving son at heart, conscious of carrying all the hopes of his parents contained in the boundaries of his uncontrollably mutinous body. He feels terrific guilt, and yet is detached from that guilt; it doesn’t stop him from fibbing constantly. He lies just as much to his friends and new acquaintances, is afraid of being “found out,” constantly, nervously comparing his own achievements to everyone else. (How on earth do people who lie such a lot keep track of what they’ve told everyone? The potential for slip-ups made me nervous as hell, just reading about it.)

There’s a certain standard-issue pose for the young person of literary ambitions in New York. Cynical and slightly bored-seeming on the outside; thirsty on the inside: disillusioned with the whole idea of “believing in anything,” exhibiting a generalized scorn of government, religion, politics and philosophy, as well as a set of received feelings about women, and about “respecting” women. Very rarely will anyone venture one syllable outside that SOP for fear of imperiling a nascent career. And understandably so, perhaps: in the fishbowl of New York media, the slightest deviation from conventional thinking is so easily magnified that the risk of being blackballed is real.

The novel issues a series of challenges to these conventions, scene after scene describing realities that fly in the face of comfortable assumptions: Why does David’s girlfriend literally weep at the success of his blog? Why do his feelings about women center so inconveniently on his desire to just have someone to have sex with, to have that taken care of? What is the closeness he seeks? Why does he lie to his parents so baldly, and so often? Why does he worry about his hair so much, constantly combing it with his hand “so it looks okay” (a gesture so painful, and so familiar?) Why should there be such uncertainty and competitiveness among young people just starting out in the world? Shouldn’t things be different? What is “coolness”? What is “success”? Isn’t it all just the most ridiculous bullshit?

We get to the coffee shop where the reading is supposed to take place, and some kids standing around outside look very fashionable, like wearing rigid denim and shoes instead of sneakers […] we can hear a girl behind us talking to a very tall guy about how Slate “spouts conventional wisdom disguised as innovative thinking — so dishonest.” I want to turn around and tell her that there are plenty of worthwhile things on Slate that are just fun and good, like the Explainer column where the writer answers readers’ questions that are related to the news, but we don’t know each other, so it might be weird to go up to a random person and tell them you disagree with them, so I don’t. […]

[The reading] is packed with about seventy-five well-dressed twenty- and thirty-somethings, many of whom are carrying tote bags from bookstores and magazines like Harper’s, magazines that I’ve never read but that seem really impressive. I remind myself that coolness is just a characteristic people ascribe to people who they only observe from afar, and that nobody is actually cool once you get to know them, and especially not people who are really concerned about how they’re dressed, but knowing that something is true and acting on it are different obviously.

The possibility for a better — a more honest — way of conducting ourselves and our relationships with others is demonstrated obliquely, in the possibilities of contact and meaning that flicker through the story. Why would anyone bother writing, or indeed living, a life that isn’t “much use to anyone”? The line comes from the Belle and Sebastian song, “Sleep the Clock Around,” a lovely and characteristically nostalgic song from a brilliant band that has become quite “uncool” (perhaps even a dreaded “dad band”!) among our younger cognoscenti. One of the novel’s particular charms is how the ultra-knowledgeable music writer David, afraid as he is of being thought uncool, tell us quite openly that he listens to Belle and Sebastian all the time with his girlfriend, because it is cool, and good, to him; that’s where liberation is to be found, in being oneself, and in telling the truth, and being open and unafraid of your own ideas, tastes, feelings, experiences, no matter what anyone else might think of you. Such a simple, banal message, “be yourself”, but in fact that is a feat one spends one’s life trying to perform. (Or not perform, rather.)

“Not being much use to anyone” becomes a double joke that recurs throughout the book, the author-David interrogating the reader about his own complicity in the hypocrisy and lunacy of the world, while the book-David, and his lovers and friends, are by turns the butt of the same joke; we all wrestle with feelings of doubt and inadequacy, and with our fears for the future, our place in the world. Is all that really stopping us from being any use? I think yes, pretty much.

The book’s cover blurb comes from Adelle Waldman, the author of The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. — another fantastic novel that revealed so much about the travails of New York’s young literati. Though both stories concern themselves externally with the difficulties young singles face in finding and maintaining an intimate relationship, the questions they pose are, at bottom, as much about literature as they are about love: about the terrible prison of emptiness inhabited by the literary careerist, and about escaping that prison just by doing a writer’s job, just by telling the truth. David Shapiro addressed this question directly in an old post on Pitchfork Reviews Reviews about a piece he wrote about dealing heroin on Craigslist; these remarks encapsulate his novel’s message very neatly, it seems to me.

Kai said his life is very bleak and lonely, and he intimated that he didn’t really have anyone else to talk to about it, and it reminded me of a quote used in a great Vanity Fair piece about going around the world looking for opium: “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.” I’m sorry to use a corny quote, but I think that just means that being honest about yourself, with yourself and other people, will make you more okay with who you are, and consequently you’ll feel better.

In You’re Not Much Use to Anyone, David Shapiro lays bare the whole of a conflict-ridden, uncertain and scary existence, even though he was only twenty-two when he wrote it. It is necessarily slight in some ways; he hadn’t had enough time yet to live very fully as an adult, but in his achievement, he is like the little brother of Karl Ove Knausgaard, a fellow literary genius who, by telling the truth of his life, transcended it; by laying claim to the whole of his humanity, transcended it.

I asked David Shapiro a few questions over email.

Did you really go to law school? Have you finished?

I have another year left of school, which starts again at the end of August. I’ve already done two years.

Are you starting work soon and if so, where?

I’m working at a white-shoe law firm over the summer, which is where I hope to work after I graduate. We find out if we get post-graduation (to begin around September, 2015) offers at the end of the summer, which is in three weeks. I work in the corporate (transactions) department, specifically the private equity group. If all goes according to plan, I will be what people refer to as “a corporate lawyer” (in the field of private equity) after I graduate.

Will you try to do both writing and lawyering? (I hope so!)

I will be doing just lawyering for at least the first two or three years of being a lawyer, and if I’m any good at being a lawyer, I won’t be writing again probably forever (although it’s hard to predict, like, where I’ll be in 20 years when I’m 45 or something). There are a few remaining things I would like to do newspaper reporting on during my last year of law school, but after that, I’m retired.

Have your parents read the book and if so, what do they think about it?

My parents have not read the book. I have a deal with them — they can’t read the book until July 22, 2024 (ten years after publication) and in turn, they get to come to the book party. I love my parents and we have repaired our relationship after I fought constantly with them from ages 13 to 21, so it’s not like we’re estranged, but I just think it would be better for all of us if they held off reading the book until the subject matter and characterizations are far enough in the past for us to laugh about it. When I wrote it, I was 22, angry, helpless, and felt like a complete failure, and I wouldn’t want how I felt then to bleed into my relationship with them now. People who read the book have a totally understandable tendency to believe that since some of the things in the book are verifiably true, everything is true, and I’m worried that my parents will think the same thing.

Maria Bustillos is a writer and critic in Los Angeles.

Hotel Ballroom Utilized

Hotel Ballroom Utilized

In his next song, which is about using his wife’s dildo while she’s out of town and is sung to the tune of ‘Love In An Elevator’ by Aerosmith, Seamonkey brings out an inflatable penis with two cans of silly string taped to the testicles, and starts to spray the crowd. Anderson and his friends howl with delight.

I mean: Maybe Weird Al was never really funny on the merits. Maybe it was mostly just circumstances, the songs’ unlikely production, that made everyone so happy. A song called “Eat It” released nationally by a major record label? On the radio? Nice. A Kickstarter to make potato salad that has raised thousands of dollars? Amazing! (But nobody’s laughing at the salad.) Maybe that’s what the merits are, with this type of thing? Just… unlikely arrangements of capital? Anyway, this dispatch from the heart of the stubbornly resilient parody music movement is worth your time.

New York Times Executive Editors Ranked, After Much Deliberation

8. Abraham Rosenthal (1977–1986)

7. Howell Raines (2001–2003)

6. Jill Abramson (2011–20141)

5. Bill Keller (2003–2011)

4. James Reston (1968–19692)

3. Turner Catledge (1964–1968)

2. Max Frankel (1986–1994)

1. Joseph Lelyveld (1994–2001)

1 Dean Baquet has not held the job long enough to qualify for this listicle.

2There was no executive editor between 1969 and 1977.

Elon Green is a freelance writer.

Photo by Scott Beale

The Beauty of a Pissing Contest

by Matthew J.X. Malady

People drop things on the Internet and run all the time. So we have to ask. In this edition, writer Cat Ferguson tells us more about a weeklong pissing contest she undertook with her roommates.

i told my roommates about this study and now they’re measuring how long it takes them to pee http://t.co/XaLLEnn7Hp pic.twitter.com/MtliELwqEQ

— cat ferguson (@biocuriosity) June 25, 2014

Cat! So what happened here?

I just moved back to New York City after moving away in 2010 for school. I’m subletting in a loft where I don’t have walls or a door, which is a little terrifying and weird, especially since I’ve spent the last three years either living alone or with somebody I was sleeping with. And now suddenly I’m basically in a giant studio with three strangers named Grace, Alex, and Ari.

A friend sent me a press release about this study that found all animals, regardless of their size, pee for the same amount of time: 21 seconds. This seems crazy! So as I was lying on my bed I told everyone in the living room (using a normal speaking voice, despite the fact that I’m on the “second floor”) about the study. The reaction was generally “Whaaat? No way.”

None of us can remember who suggested the experiment. It came about pretty naturally: Everybody time yourself when you’re peeing; we’ll see if it’s really 21 seconds. Throughout the week, I started questioning our methods — shouldn’t we have labeled them with our initials or something? Should we be taking notes? Some of us were using our phone, so half of us had milliseconds and half of us were just counting in our heads. I thought about these methodological problems a lot while I was peeing, but also at other times, like while sitting on the train.

We all got together over beers to answer your questions.

What were the results of the experiment, and what are your thoughts on it?

Cat (pre-experiment average pee time guess: 19 seconds):

OK, so rounding the millisecond ones to the nearest whole second, my average was 18 seconds. That makes sense to me? Maybe we’re all dehydrated.

Grace (pre-experiment average pee time guess: 22 seconds):

My confession to you is that I am the quickest pisser in the house. I struggle to reach 13 seconds. And I average like eight seconds. I’m also the worst reporter in this whole thing. It made me feel inadequate. I’m losing in a literal pissing content. I just stopped recording my times. I’d start timing and then be like, “Ahh, what’s the use?” And how bad I had to pee was not necessarily related to how long the piss was. I would be like, “I have to pee so bad, this will be a great time,” but then it wasn’t!

Alex (pre-experiment average pee time guess: 24 seconds):

I peed for 15 seconds like three times! Six seconds, 37 seconds, it’s all me. I didn’t ever factor in my drinking, but I can tell you drinking was a factor in making me pee more. Also, I think you pee less when you have to poop.

Ari (pre-experiment average pee time guess: 21 seconds):

Sometimes it was very short. I think I pee quick — not just in time, but like, the strength of the stream.

Lesson learned (if any)?

Cat:

People love talking about bodily functions. I’ve brought this up a couple of times with people in the last week, and almost every time it’s launched a really intense conversation. I’ve learned a whole lot about people I just met. One guy told me, “I don’t pee when I need to. I pee when it’s like, ‘I want to leave my desk, or I don’t want to see my boss, or like, oh, I’m here, I’m flossing, might as well piss.’”

Ari:

Can I talk about the empirical process? I studied economics in college, so I had to put aside my normal stickler-for-rules thing, because we were just timing our pees in the bathroom. I thought everyone collaborated really well, which I love. The lesson learned is we could do something for a week. I have serious commitment issues, but we really did it! I was proud of us.

Alex:

Even before this experiment, I always timed myself, like, “Let’s see if I can get 30 seconds.” When I was in grade school, my friends and I would be in the bathroom, and we’d stand next to each other and race to see who could go longer. And there was a kid who was like, “I always pee for 20 or 30 seconds.” I have a lot of random memories, and that’s one of them. I remember when [my friend] Michael said he could pee for 30 seconds.

Grace:

I’m a short pee-er, and I just have to live with that knowledge now.

Just one more thing.

It’s not so bad living in a giant studio with a bunch of strangers! Especially ones who are willing to talk about their pee on the Internet for their subletter’s entertainment. Also, for the record, after hearing about the experiment, Awl pal Brendan O’Connor went to the restroom at the Swallow Cafe and reported a pee time of 26 seconds, counting in his head.

Matthew J.X. Malady is a writer and editor in New York.

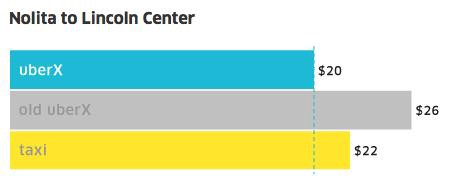

The Uber Bomb Detonates in New York

Have you been in a New York cab recently? Sometimes prompted but more often not, drivers will want to talk to you about Uber. If you’re in a yellow cab or a livery car, you will hear about Uber the virus, Uber the interloper, Uber the merciless invader; if you’re in an Uber cab, or an Uber-adjacent green taxi, you’ll hear about Uber the inevitable, Uber the strange, Uber the great (for now). It’s been a boom time for untethered drivers — a magical stretch during which they could take advantage of high fares, high demand, and low barriers to entry all at once. It was acknowledged, rarely explicitly, that the arrangement felt strange and temporary — the product of an imbalance, not a new status quo.

This has been imagined in the press as a battle between unregulated drivers and their super-regulated counterparts. But that’s not it at all! This was, and is, and will be until Uber’s billion dollars either runs out or multiplies itself, Uber against the world. Look what they did today:

We just dropped uberX fares by 20%, making it cheaper than a New York City taxi. From Brooklyn to the Bronx, and everywhere in between, uberX is now the most affordable ride in the city.

Haha, first of all, “the most affordable ride in the city” that is in a car, driven by another human, for your individual transportation, maybe. Uber’s style is too consistent for its announcement post to be called tonedeaf; it’s a company that wears its fuck-you, get-mine philosophy on its sleeve. Its price examples have riders going from Williamsburg to the East Village, from Grand Central to the Financial District, from Nolita — Nolita! — to Lincoln Center. From your LOFT to FASHION WEEK, from the TRADING DESK to THE TRAIN TO YOUR LARGE DISTANT HOME, from your STEEL RESIDENTIAL ARCOLOGY to your TASTING MENU, Uber will save you two dollars.

Here are some people who will be happy about this: Uber riders. Here are some people who will be upset about this: Anyone who drives a car professionally in New York, by far America’s most cab-dense city. When Uber has dropped prices like this elsewhere, it has temporarily made up the difference for drivers. Not here! The volume is too high, the cost too great. What are all the new Uber drivers, with their freshly depreciated new Uber-financed rides, supposed to do now that their per-ride take has just been slashed by a fifth? That the conditions that lured them to this odd new company have changed? They mustn’t complain, else their Uber star rating fall by a star and they get purged from the system. So they’ll just keep driving, and we’ll keep riding, until one day we find ourselves standing on the street corner with our arms up, phones dead, hailing ghosts.

Brutalism Briefly Unbullied

Paul Rudolph’s cube-y little marvel of building, the Orange County Government Center in Goshen, New York — one of the many Brutalist buildings subjected to whinnying opposition by faux-aesthetes — is one step closer to salvation. The county has agreed to entertain hotel designer Gene Kaufman’s proposal to renovate the building and transform it into “a center for artists, exhibitions and community meetings.” Photo

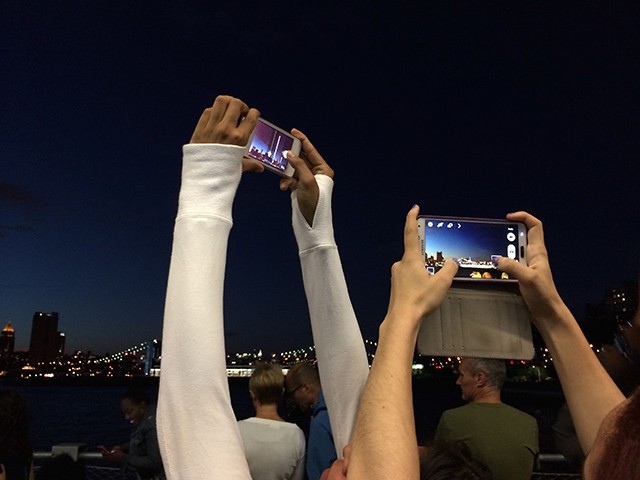

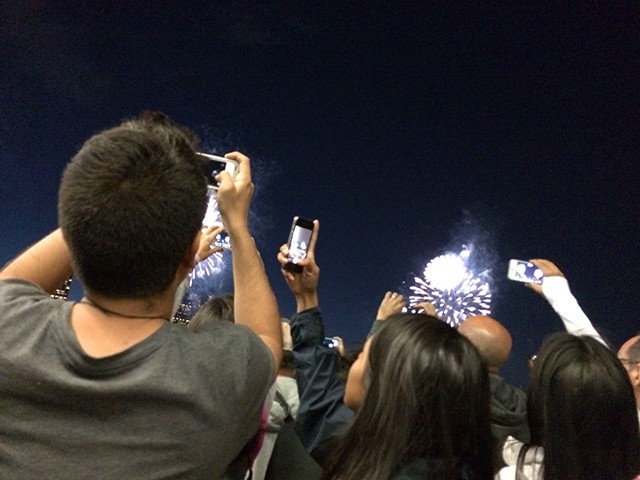

Put Your Phone Down

As a people we have lost the plot. Because we can document everything, we will, and we can’t stop. Every event is now a sea of people with their arms held up in a triangle, forming an illuminati symbol with our phones at the apex. We’ve gone too far. It has to stop. Like a Beyoncé concert, the New York City fireworks were a nightmare of phones, and for what? For nothing. Data for your cloud. You can fully understand why performers — and brides and grooms! — want to ban all cellphones at events.

Take a picture of a flower, a baby, a cat, a sidewalk, an airplane, a painting, please. Please do! It’s wonderful that we all have instant access to an artistic practice that was once expensive and elitist. But the compulsory documentation of everything is monstrous. Let it stop with you.

The fireworks as seen from Brooklyn Bridge Park were beautiful. I don’t even really like fireworks! As a tall person, I was happy to be able to see through your arms and around your phones. I hope you’re treasuring all those photos right now.

Life and Death on the Bear Cam

Life and Death on the Bear Cam

The bear cams are back: Feeds from Katmai National Park in Alaska are going live this week. Some are powered up already and in testing; others are still coming online. The bear cams have become an odd yearly ritual for the nature-obsessed and vocationally computer-bound alike, developing an avid fan base that tracks the comings and goings of dozens upon dozens of feeding bears. Each year the cameras get better, their hours longer, and their stories richer.

So what will happen in 2014? What are we in for? I called Roy Wood, Chief of Interpretation for Katmai National Park, who helps run the cams. He told me a story from a few years back.

First year, toward the end of the season, there was a story arc, if you will. A thing called a bear cache, or a kill cache — when bears kill something larger than they can eat in one sitting, like a moose or a caribou, they pile up a bunch of debris on it. Grass, leaves, dirt. Then they sort of camp out by it, until they’ve eaten it all or grown tired of the leftovers, and then they move on to something else.

A cache appeared one morning. In October the hours are pretty short. We still have long days, but the solar intensity was such that we couldn’t keep the cams running all day, so they were running from about eleven in the morning and going off at about four. So, at eleven o’clock the cam comes live on this beautiful weekend, and there’s this big pile of grass and dirt directly in front of it. There’s a bear sitting on top. Most people have never heard of [a bear cache], or seen it; even people that work around bears all the time don’t have such a great view of kill caches, because you don’t want to get anywhere near them. That’s one of the most dangerous situations you can find yourself in.

But here it was, smack dab in front of the camera. And this is a bear we didn’t see very often. Luckily, this bear had a diamond patch of much lighter fur on its side, so it’s very easy to pick out. It’s one we didn’t see that often because he’s very shy around people; he really doesn’t show up until most of are gone from the camp.

So he’s on this cache, and we don’t know what’s in it. He never pulls anything out and eats it while we’re there. The camera goes dead at four o’clock.

Then, next morning, the cache is twice the size, and there’s a different bear on top. Much larger. A bear that’s been known to kill other bears. So now there’s this mystery — did Lurch, the new bear, kill this other bear? Is he now buried in the cache too? Of course the camera goes dead before we know what’s happened.

We’re off for the holiday weekend, and I get back to the office. I talk to a few people who are out at the camp and they say, yes, it’s definitely a bear in there.

I power up the cameras so I can take a peek around, and see what’s going on before the cameras go live. I see a bear’s foot sticking out of the cache.

Wood, looking forward, is excited. “From the time the cams go live until they end, there’s always something going on,” he says. He expects a good year, but that’s about as specific as he can get. His story continues:

We tell the operators not to zoom in too far, you know, not to make people sick. But this is a rare opportunity to see nature uncensored, as it actually happens out there. And it’s a wonderful scientific opportunity, because we couldn’t get that close to the cache if we were out there.

You can imagine that when we found out it’s not a moose, it’s not a caribou, that people were very upset about it. They were upset with Lurch, and they were worried about the safety of all the other bears. They didn’t like Lurch already, because they knew about his behavior in the past. Some of these people had seen footage of him killing a cub in 2006, a cub from one of everybody’s favorite bears.

People knew about his habits. Immediately people start assuming he had killed this other bear, which they had started calling Patches, and the conversation was around: When is the park service going to take care of the problem? Because he’s a murderer, a serial killer, a threat.

These were human-value-laden words. So I’m on the cameras, engaging people with this. I’m not telling them they’re wrong, but I’m trying to tell them to think from a bear’s perspective. Protein is protein. This kill virtually ensures his ability to get through the winter.

By the end of the week, I was so proud of the people on these cams, because they went from complete horror and disgust and disdain for this animal to using words like “power” and “strength” and “survival” and “tenacity.” And that’s exactly, sort of, the goal here — to get people to have respect, and a deeper understanding.

Bear cams, man, they change you. Here are the links for this year:

— Brooks Falls

— Lower River

— River Watch

— The Riffles

What ever happened to Lurch, anyway?

The last time he was seen was right at the time of the government shutdown. He was not seen on the camera, but by people who were packing up after they were told they needed to get up and get out of there. He had killed another bear; it’s something he does frequently. He had another bear buried in a food cache near the campground. That’s the last any of us have seen of him.

Eyes peeled.

Some Notes on the Iranian Minister of Foreign Affairs' Video Calling For "Mutual Respect" in...

Some Notes on the Iranian Minister of Foreign Affairs’ Video Calling For “Mutual Respect” in Upcoming Nuclear Talks

1. It begins beautifully when, looking dapper in a beautiful suit and sunglasses, he emerges from a beautiful building to walk past a beautiful fountain.

2. As Zarif strolls, we see the person who opened the door of the beautiful building for him has, strangely, neglected to close it. What are they waiting for?

3. There’s a very weird jump cut around 1:12 from a close-up to a wider shot as a sort of punctuation around his chastising the United States for eight years of sanctions:

“They then opted for pressure and sanctions. For eight years.”

“The sanctions were crippling.” (Now I’m standing in a whole new place!)

4. There’s a truly bizarre lol cut at 1:44 where, now, suddenly, Zarif is not looking at the viewer but off to the side, into the distance. Who is he talking to??

5. For the entire four-and-a-half-minute video, Zarif manages to look both full of conviction and purpose and super annoyed that he even has to do this shit.

Sarah Miller is the author of Inside the Mind of Gideon Rayburn and The Other Girl. She lives in Nevada City, CA.