The Poster for 'Spectre' Is Fake, Right? It Has To Be.

by Brian Feldman

I mean, holy shit. Look at it again.

It is the year 2015, and everything touched by a major movie studio — certainly the 24th installment in one of the medium’s most enduring franchises — is a/b/c/d/e/f-tested TO DEATH and this is the poster we get.

“Hmmm… okay here’s what we’re gonna do: let’s put James Bond on the poster. Nice, nice. White tuxedo. Very fancy. Annnnnd that’s it.”

[assistant turns to leave]

“NO WAIT. Okay, he’s a secret agent, right? Like, he’s the gun man? Can we give him a gun? Let’s do it. Give him the gun. Put a silencer on it. He’s a secret agent and they’ve always got the pew-pew-pew cylinder on the end of their tiny guns. Have him holding the gun. That way we know he means business.”

[assistant turns to leave]

“NO WAIT. Does he mean enough business? What’s another sign of meaning business. Money, obviously, but I mean the fighting business. Have him cross his arms. Yeah, he’s pointing the gun and crossing his arms. This is very good. Read that back to me?”

“James Bond, holding gun, arms crossed, white tuxedo.”

“Perfect. Print one million copies.”

[assistant turns to leave]

“Sorry, change of heart. Two million copies.”

[assistant turns to leave]

“NO WAIT. We gotta put something in the background. What’s the movie called? “Spectre”? He fights a ghost? Finally, I have been saying for years that James Bond should fight a ghost and he finally is. Put a ghost in the background. Also, ‘Spectre’ is a dumb name let’s see if we can still change it to ‘James Bond VERSUS Spooky Ghost.’ Please see yourself out, I have to yell at iTunes again.”

[assistant turns to leave]

“NO WAIT. Okay change the ghost to a skeleton? That’s much scarier than a ghost. Make it really obvious that the skeleton is smiling or laughing? Make it, like, a funny skeleton. He should be looking over his shoulder, with an expression like, ‘Who, me?’”

[assistant turns to leave]

“NO, WAIT. Put the skeleton in the fanciest top hat you can find.”

[assistant leaves]

“Finally, alone at last. Me, the smartest film executive in the world. The man who put the fancy skeleton on the secret agent poster.”

Digging the LowLine

by Kevin Sweeting

If you stand on the end of the platform shared by the J and M trains in the Delancey-Essex Street subway station and squint past the rails of the M line, beyond the columns supporting the street traffic above, you can see a gloomy-looking expanse of empty space pocked with puddles and ringed with graffiti. A bit more than an acre in size, the cavernous rectangle stretches for three blocks below Delancey Street, between Essex Street and Clinton at the mouth of the Williamsburg Bridge.

Opened in 1904 as the Essex Street Trolley Terminal, the space served as a depot for streetcars operating along the bridge’s Brooklyn-bound trolley lines until 1948, when private trolley service over the bridge was suspended and control of the space was transferred to the newly formed MTA. No longer running streetcars, and without an obvious need for their strange vestigial infrastructure, the MTA had the space sealed and abandoned it.

A few years ago, two thirtysomething friends, Dan Barasch and James Ramsey, decided that the space should be a public park — a subterranean science-fiction cousin to the High Line’s verdant boardwalk, called the LowLine. They proposed using an arrangement of lenses and tubes to collect natural sunlight from the surface and pipe it below, illuminating the space and supporting photosynthesis in what they are calling “the world’s first underground park.” In much the same way that the High Line’s modern repurposing of underused infrastructure redefined a long stretch of West Chelsea, the LowLine founders describe their project as “not merely a new public space, but an innovative display of how technology can transform our cities.”

The LowLine’s crusade to carve a park from an underutilized corner of belowground transit infrastructure is an innovative solution to a persistent problem: Community parks are a public good, and the Lower East Side is a neighborhood severely lacking in green space. The LowLine could be a subterranean respite in a neighborhood where real estate prices on the surface are inhospitable to the idea. What seems left unconsidered, however, is how it would fit into the future of a changing Lower East Side — and whose priorities “the world’s first underground park” would service.

The duo, who first conceived of their subterranean park in 2009, are not idle dreamers pitching fantasy civic projects for fun. Ramsey is the owner of the Lower East Side design firm Raad Studio and an ex-NASA engineer, while Barasch clocked stints at Google and UNICEF before moving into an executive role at PopTech. Hoping to bring their idea to fruition, Barasch and Ramsey followed a roadmap to success plotted by the Friends of the Highline and set up the Underground Development Foundation, an organization under which they could organize and advocate for the project, and began working with a real estate consultancy firm on an initial “scoping exercise” of the terminal space. In September of 2011, a quick look at the LowLine’s proposal was publicly unveiled on New York’s Intelligencer blog. People really liked it.

The technology behind the project has a kind of irresistible science fiction appeal: A series of parabolic mirrors stationed aboveground collect the sun’s rays and direct them below through a series of “irrigation tubes,” which pipe the sunlight across an undulating canopy that works as a fixture to splash the light across the terminal space. In the days following its online debut, the project’s psychedelic renderings and intriguing pitch for innovative, public green space became a mini-sensation and birthed a wave of stories on sites from CNN to InHabitat to Web Urbanist. The Architect’s Newspaper said it “could become the next park phenomenon”; Business Insider reported that the “ambitious underground oasis” had “New Yorkers buzzing with excitement.”

By the end of that year, the Underground Development Foundation was well on its way to being officially recognized as non-profit 501(c)(3) and Barasch and Ramsey had taken meetings to discuss their plans with Jay Walder, then-head of the MTA, as well as the commissioner of the city’s parks department at the time, Adrian Benepe, the city’s Economic Development Corporation, the Lower East Side Business Improvement District Board, and a string of possible wealthy supporters.

With interest mounting, in February 2012, Barasch and Ramsey launched a Kickstarter campaign with the goal of raising a hundred thousand dollars to build an initial “full-scale installation” of the project’s remote skylight technology. The founders acknowledged that the LowLine park itself was still several years — and several bureaucratic leaps — in the future, but hoped that the functional prototype would be the process’s first step, an “invaluable tool in helping convince [the] community, potential funders, the City, and the MTA that this idea can work.” Online coverage continued to flow, with stories at Fast.Co.Design, The Huffington Post and the Wall Street Journal. Hundreds of others followed. Kickstarter Co-Founder Yancey Strickler shouted out the project in a segment on CNN and highlighted it as the site’s Project of the Day. On April 6th 2012, the LowLine’s crowdfunding campaign closed, having easily blown past its initial goal to collect one hundred and fifty-five thousand dollars from thirty-three hundred backers.

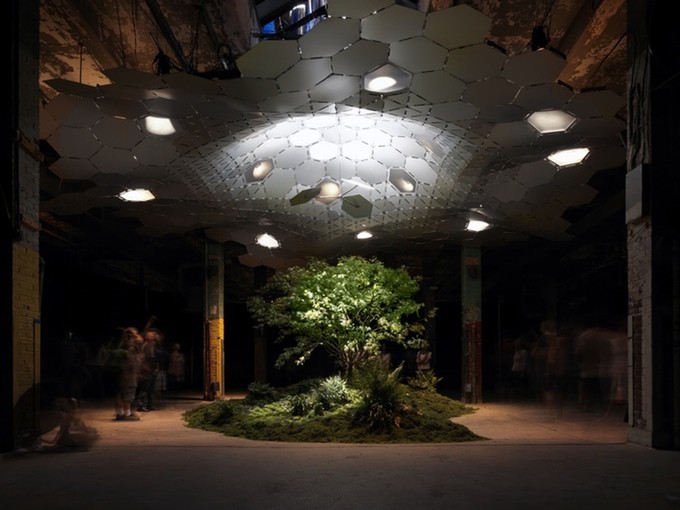

That proof-of-concept installation, dubbed “Imagining the LowLine,” opened for two weeks in September of 2012 as a kind of public preview. The windows and skylights of the hosting warehouse were covered, while a solar collector on the roof piped light into a canopy fixture hung from the rafters. The fixture, a swooping circus tent of anodized-aluminum panels, released the light in slanting shafts that cut across a small mossy knoll topped by a single Japanese maple and prowled by a praying mantis the founders started calling “Zoltan.” The scene looked like a miniature sci-fi version of a Hudson River School painting.

During its two-week revue, the “Imagining the LowLine” exhibit played host to events and fundraisers and food carts. In all, eleven thousand people came to poke around. An online piece from the New Yorker favorably compared arriving at the mind-bending exhibit to Alice’s long tumble into Wonderland, saying “it seemed obvious why the LowLine needs to exist.” As a demonstration of the technology and the intrigue around space, the exhibit appeared to be a triumph.

The next two years were spent on a quieter campaign of political networking and fundraising. In order for the Essex Street Trolley Terminal to become a park, control of the space would have to be transferred from the MTA to the City’s Economic Development Corporation, which could designate it a public space and place it under the auspices of the City’s Parks Department, who would in turn partner with the LowLine’s Underground Development Foundation to build and run the park. But the unstaffed and underfunded New York City Parks Department already oversees some five thousand properties across the five boroughs, so creating new park space — especially experimental, underground (or elevated!) park space that will cost tens of millions of dollars to build — does not generally rank highly as a city priority.

The LowLine’s spiritual predecessors at the Friends of the High Line were able to shepherd their project to fruition by raising money independently, working to refine their idea, assembling political support, and laying out their primary plans while staving off the need for city involvement until all the pieces were in place — a path the LowLine also hopes to walk. In a 2012 interview, Ramsey mentioned that Friends of the High Line co-founder Joshua David was one of the first people he discussed the LowLine concept with. Both David and Robert Hammond, the Friends of the High Line’s other co-founder, sit on the LowLine’s Advisory Board. Unsurprisingly, fundraising plans for the LowLine closely mimic the efforts undertaken by the Friends of the High Line as it worked to support its initial planning efforts and contribute to the promenade’s initial construction. In that vein, the LowLine group and its Board of Directors spent 2013 and 2014 hosting a string of fundraising dinners and big-ticket parties aimed at simultaneously boosting the Underground Development Foundation’s coffers and currying favor amongst a network of wealthy supporters and celebrity advocates.

This type of private philanthropy is a model widely embraced by privately funded conservancy groups looking to bridge the gap between ambitious park plans and the anemic reality of the city’s municipal budget. Many New York City parks — Bryant Park, Madison Square Park, and Hudson River Park, to name just a few — are supported by organizations that supplement the money allocated to them by the Parks Department. Frequently, they pay for much more than the city does — seventy-five percent of Central Park’s budget is covered by private donations — and so these conservancies and “Friends” organizations often handle design decisions, staffing, programming, maintenance and usage decisions. Ninety-eight percent of the High Line’s yearly operating budget is covered through donations routed through the Friends of the High Line. In July 2014, Ramsey mentioned to The Architect’s Newspaper that the LowLine had ”several seven-figure pledges.” Three months later, tables at the organization’s 2014 “Anti-Gala” hosted by Spike Jones and Lena Dunham sold for twenty-five thousand dollars. This October, Anti-Gala attendees can purchase a hundred-thousand-dollar “Visionary Table.”

The LowLine’s strategies for securing control of their site and navigating local government bureaucracy have also closely paralleled those of the Friends of the High Line; publically available tax records from 2012 indicate that the LowLine paid James Capalino, a prominent real estate lobbyist and an early member of the Friends of the High Line’s Board of Directors, nine thousand dollars to “lobby state and local officials and officials of the Transportation Authority to gain their support” for the project. In July 2013, the project took a major step forward when nine New York politicians, including Senators Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand, Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, and the then Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer, collectively sent a letter officially urging the city’s Economic Development Corporation and the MTA to begin discussing transferring control of the trolley terminal to the Park’s Department and the LowLine organization, citing the benefit the project could bring to neighborhood through “increased sales, hotel and real estate taxes and incremental land value” as a “year-round public amenity, [that] will be a draw for tourists and residents alike.”

With a string of successes behind them and big time money and political support falling into place, the LowLine seemed poised to spring from idea to reality. Oddly though, the LowLine’s public forward momentum appeared to slow, and in June of this year the team returned to Kickstarter and asked for two hundred thousand dollars to fund a exhibition space they are calling the LowLine Lab. The campaign page, illustrated with the same renderings that accompanied the first, explained that the LowLine team plans to build out a “laboratory” space to test three things: the performance of their solar technology, the flora to be used in the space, and the social and community value of the LowLine, a pitch that closely resembled the stated goals of the group’s previous “Imagining The LowLine” exhibit. On July 8th 2015, the LowLine closed out its second successful Kickstarter campaign, collecting over two hundred and twenty-three thousand dollars from more than twenty-five hundred backers. The LowLine Lab, which is scheduled to open this month, will be a kind of “open studio” — a working research space opened up for public visits.

The economic benefits touted by those nine New York politicians in their letter supporting the LowLine project come from an economic impact study undertaken by HR&A Advisors, a power-brokering consultancy firm known for its key role in the creation of the High Line, and which appears to have worked closely with the LowLine team even before Barasch and Ramsey debuted the project to the public. HR&A completed the survey in 2012 in an effort to generate momentum for the LowLine idea by showing the positive effect it would have on development projects being proposed for the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area, or SPURA, a stretch of prime real estate property immediately adjacent to the Essex Street Trolley Terminal that was then slated for redevelopment.

The LowLine has not publicly released HR&A’s report, but it did circulate the document privately amongst local politicians and developers. The most public attention the study received was a Wall Street Journal piece published on Christmas Day 2012 which presented HR&A’s finding that the LowLine “would boost land values of SPURA sites by between $10 million and $20 million and create between $5 million and $10 million in sales, hotel and real-estate taxes.” The article continued:

The LowLine backers say in the summary that they will seek to raise $55 million, figuring the actual cost will be in a range between $44 million and $72 million, including donations and between $7 million and $14 million in tax credits.

With a projected annual operating cost of between $2 million and $4 million for the LowLine, the summary notes the goal of the park would be self-sufficiency, aided by revenue from programming festivals, performances, private events, public art and children’s programming. Commercial space is also planned.”

The Seward Park Urban Renewal Area is an expanse of city-owned parking lots and low-rise buildings stretching for several blocks down Delancey Street that has stood mostly vacant and underused since 1967, when the city leveled blocks of apartment buildings, displacing about eighteen hundred predominantly Puerto Rican families. Since then, calls for SPURA’s redevelopment had languished in the corrupt political cesspool of Albany, but in 2013 — after entertaining proposals from nearly all of the city’s major development companies — then-mayor Michael Bloomberg and his consiglieres at the city’s Economic Development Corporation unveiled plans to transform the dormant SPURA space into Essex Crossing, a 1.65 million-square-foot mixed-use, multi-building complex clustered around the intersection of Delancey and Essex Streets. Ground was broken on phase one of the project, which is being spearheaded by Delancey Street Associates LLC — a umbrella organization of investment partners and local real estate developers — earlier this year.

Essex Crossing is unprecedented in its scale, with all the hallmarks of a Bloomberg-era redevelopment project: The six-acre complex is spread across nine separate plots of land and is scheduled to be in various stages of construction for the next decade. When complete, Essex Crossing should comprise hundreds of thousands of square feet of retail space, dozens of restaurants, swaths of new office space, a badly needed grocery store, a new home for the Essex Street Market, a fourteen-screen multiplex, a museum space,a fifteen thousand square foot public park, and one-thousand apartments, about half of which will be permanently designated affordable.

The 1.1-billion-dollar project will undoubtedly bring further change to the look and feel of the already-gentrified surrounding neighborhood — where luxury development is quickly erasing what’s left of its history as a working-class pocket in Lower Manhattan — as well as introduce waves of a new class of commuters, tourists, commercial tenants, and residents to the area. At the center of all this change could be the LowLine.

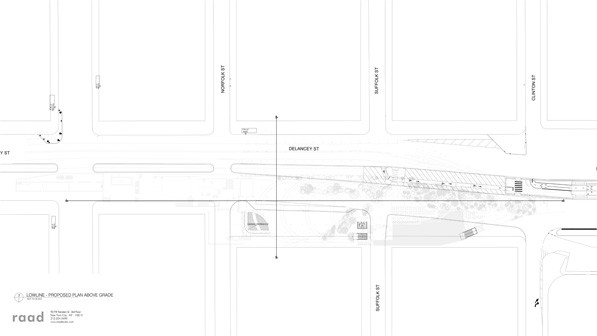

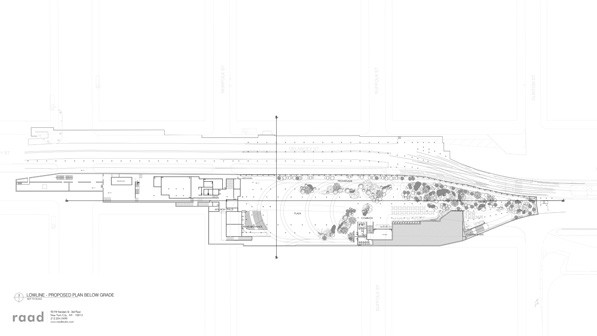

Renderings for Essex Crossing reveal plans for a ninety-thousand-square-foot subterranean retail corridor connecting the basements of the complex’s three largest buildings, each of which will occupy a block-long parcel of Delancey Street, stretching from Essex to Clinton Streets. Dubbed the Market Line, that space will be anchored by an expanded Essex Street Market and host a new outpost of the Smorgasbord food hall, “incubator spaces,” and dozens of upscale retail and specialty food shops — kind of like an underground Chelsea Market. It would also sit immediately adjacent to the LowLine’s proposed home, directly below the automobile traffic chugging along that exact same three-block length of Delancey Street. A proposed aboveground site plan that Ramsey’s RAAD Studios shared with QDB Magazine in 2014 shows what appear to be entrances to the Lowline sprouting from the sidewalk on the corner of Norfolk and Delancey Street, immediately outside Essex Crossing building no. 3. Similar plans for the LowLine’s below ground space show it sharing a southern wall with Essex Crossing’s northern boundary. The two projects are immediately next to one another.

In a 2014 interview with The Lo Down, a Project Manager for Essex Crossing named Isaac Henderson called the LowLine a “tremendous opportunity to both give us visibility and access to sites 3 and 4 [Essex Crossing buildings], the Market Line space, and, in a perfect world there would be both connections between the LowLine (and the Essex Crossing project).” Henderson continued to explain that the Essex Crossing developers were “friends” with Barasch and Ramsey and that the two projects had discussed the possibility of connecting and shared their plans with each other. When I spoke with Dan Barasch on the phone in late June, he confirmed that the two organizations have shared initial plans and have a “really constructive dialogue” and “a strong capacity for partnerships” but reiterated that official plans for access between the two projects hadn’t been finalized.

The financial benefits the LowLine could bring to SPURA’s future developments as outlined in HR&A’s economic impact study did not go unnoticed; the team behind Essex Crossing was not the only candidate for redeveloping the SPURA parcels that noted the possibility of having the LowLine as an adjunct or extension of their space. Barasch told me that the LowLine had worked on plans with several of the original groups that had submitted redevelopment proposals for the space and that several of those developers, including the group behind Essex Crossing, had contributed to the LowLine’s private fundraising efforts over the years.

The LowLine is expected to cost upwards of fifty-five million dollars to build, the majority of which Barasch and Ramsey expect to come from private philanthropy, both personal and corporate. Space — even public space — that is created with funding from private interests is always going to privilege the needs and preferences of the interests funding it. The High Line is again a wonderful example. Financed in large part through a system by which real estate developers with projects in the surrounding area could expand their buildings beyond the area’s standard zoning limits in exchange for donations to a High Line Improvement Fund — and supported on many fronts by wealthy Chelsea residents — the High Line, which has no playgrounds for local children and is light on space for public assembly, but offers a nice stroll over to the shops at Chelsea Market, has stimulated billions of dollars in new development and helped raise property values along its snaking corridor by a hundred and three percent. The debate around the High Line’s success as a community space continues, but in purely economic terms the value it brought to the neighborhood undeniable. That is a benefit surely appreciated by the High Line’s most generous private benefactors, Barry Diller and Diane von Furstenberg, who live in the neighborhood, own businesses headquartered within a block of the High Line, and who have given a total of thirty-five-million dollars to the elevated promenade over the past five years.

The group behind Essex Crossing is not the only party with an interest in bringing the LowLine to the Lower East Side. LowLine Board member Peter Shapiro, the owner of Brooklyn Bowl and Port Chester’s Capitol Theater, recently became a partial owner of the Slipper Room, a burlesque theater about one-third of a mile from the LowLine’s proposed home. Shapiro is joined on the Board by David Barry, the President of Ironstate Development Company and a Fortress Investment Group board member. Ironstate oversees development projects in New York and New Jersey worth somewhere north of a billion dollars; it recently rehabbed the nearby Cooper Square Hotel into the Standard East Village (shitty cocktails but some decent reds by the bottle). Zach Aarons, the youngest member of the LowLine’s board, works in real estate development at Millennium Partners and is a venture capitalist who lists investments in “seed rounds or Series A rounds of technology companies mainly in real estate tech” in the “What I’m Looking For” section of his AngelList profile. Earlier this year he started a “real estate technology accelerator” called MetaProp.

It is no surprise that the LowLine, a project that has taken deliberate steps to highlight the role it could play in increasing the value of the surrounding real estate, is being supported at the highest level by people with financial and ideological interest in the continued growth of New York’s real estate value. That someone would look ahead at Essex Crossing’s years-long, 1.1-billion-dollar project of neighborhood redefinition and think, “what else can we do to raise property values in this area” is as best a summary of New York real estate as I can find. That supporting the LowLine can be favorably framed for the public as the creation of “green space” without having to actually sacrifice any of the area’s incredibly valuable surface-level square footage, is obviously another added benefit.

With a clear path to success marked out ahead of them, and with the support of local interests and well-connected board members supplementing the enthusiasm radiating off the peanut gallery of crowdfunders, the LowLine campaign has succeeded in cultivating a sense of inevitability that pushes us to imagine the finished space. The question at hand isn’t so much whether the LowLine will happen, but what it will look like when it does.

Officially, the LowLine has played close to the vest with details on how the space will look and how it will function day-to-day. Barasch has mentioned preliminary plans for a densely planted “ramble” accompanied by a gallery, a grassy common, and a plaza for hosting events and programming. The preliminary concept renderings that have been used to illustrate the project proposal show a kind of science fiction-y cathedral space dotted with families and people strolling past fountains and lounging on grassy knolls. The LowLine has been consistent in its plan to create “green space” on the Lower East Side — one of the most intriguing parts of their solar technology is its ability to support photosynthesis — but the vision we’re shown for the “world’s first underground park” doesn’t much resemble any traditional conceptualization of green space or “the outdoors” in any immediately recognizable way, and a consideration of the realities of the underground terminal and how it will function reveal the contours of a very different possibility.

In large part, it is the LowLine’s defining quirk, the fact that it is underground, that really complicates things. Public space isn’t by definition outdoors, and New York City is full of publically accessible indoor atria and plazas, but park space, urban park space in particular, is generally expected to serve a neighborhood function, or at the very least serve as a respite from its visitors’ crowded apartment buildings or antiseptic offices.They are spaces largely cherished as an escape from the rougher edges of urban living and the crowding and intensity of the urban landscape. On a more micro level, parks work as informal, democratically accessible gathering spaces and venues for community activities. People can play basketball or skateboard on swaths of blacktop, couples lounge on patches of grass, kids play on playgrounds, families barbecue, people stroll around or bike or jog or take in the scene, annoying Columbia students throw around Frisbees. Even the High Line, which doesn’t really functionally resemble a park in any traditional sense, offers breezes and people watching and opportunities to take in the skyline or catch views of the Hudson River. All of this, of course, would be impossible inside the LowLine.

Lacking soil, all the plants would be potted or bedded in planters. The Essex Street Trolley Terminal space is part of the New York City subway system. Temperatures in the Delancey-Essex Street subway station hit nearly ninety degrees this summer. When I spoke with Barasch, he explained that the project’s engineers are working on some sort of demising wall to seal off their space from the station’s active tracks and a ventilation system to help control the space’s temperature. But, as the Two Bridges Neighborhood Council Associate Director, Kerri Culhane, has pointed out before, there would be no breeze and no view

. On overcast days and in the evenings, when sunlight is rare, the space would be lit by artificial light. You would walk through a door to get inside. The overlap the LowLine would have with the spaces we recognize as parks seems slim.

In function and design, the LowLine is really an atrium. Tellingly, HR&A’s Economic Impact Study names the David Rubenstein Atrium at Lincoln Center and Apple’s underground store on Fifth Ave — both of which are retail atriums, neither of which are parks in any any sense of their set up or use — as models for the LowLine. City ownership and ostensibly democratic access qualify the LowLine as public space, but it can hardly be heralded as “the world’s first underground park” without first retooling any colloquial understanding of the word.

The LowLine is not without its merits. The design of the space is prepossessing and would offer access to an otherwise unused piece of fascinating New York City history. And, on a certain level, it is idiotic to argue against adaptive reuse of unused space. There is also an undeniably impressive technological appeal. From a design perspective, the solar irrigation technology seems innovative and necessary in a way that so much new technology, particularly environmentally conscious technology, can only grasp at. Imagine the ecological benefits that could come from offsetting even a small percentage of our daytime light usage with bottled sunlight. Imagine the benefits solar irrigation could bring to innovative indoor farms like Ecopia, or the forthcoming flood of marijuana operations.

So, while it is hard to deny the initial appeal of the LowLine’s futuristic concept, the draw it would have as a repeat destination for Lower East Side residents, once they’ve paid their visit and satisfied their curiosity, is harder to see. The Bodies Exhibit didn’t exactly become a neighborhood hangout. Essex Crossing’s commitment to solidifying the Lower East Side as a tourist destination, and the proposed LowLine space’s proximity to Essex Crossing’s “more destination-oriented uses on Delancey Street,” suggest a space that seems set up to cater to tourists or the single-visit curiosity of residents checking out the space or attending a one-off event. Like the seating filling the pedestrian plazas along Broadway’s mid-town intersections, or the High Line even, the LowLine seems designed to function more as a tourist benefit than as a setting for spontaneous leisure or local activity.

Barasch and Ramsey have explained that the space’s “self-sufficient” model for covering their projected two-to-four-million-dollar yearly maintenance and upkeep costs will couple private donations with programming revenue generated through “festivals, performances, private events, public art and children’s programming” and from the leasing of commercial space. Engineers who have worked with the LowLine on plans for the space have said that it can hold close to fifteen hundred people; a capacity that would easily rank it among the largest rentable event spaces on the Lower East Side.

If the #Lowline transformed into your new favorite concert venue, who would you want to perform? Tag them! pic.twitter.com/VCV8RyvQhz

— the Lowline (@lowlinenyc) July 24, 2015

The LowLine’s use as an event space, and the necessary revenue it would draw from hosting those events, would likely require it to remain open into the night. A recent LowLine tweet suggests the space could host concerts, and it’s not hard to imagine it becoming a popular venue for fashion shows or public exhibits. The High Line has had success employing a similar supplementary funding model by renting exclusive access for parties and events at various points along its thoroughfare through a partnership with the Skylight Group, a event production company known for specializing in “large, distinctive, typically historic locations.” Jennifer Blumin, the founder and president of the Skylight Group, sits on the LowLine’s Board of Directors and is married to LowLine co-founder James Ramsey. The Slipper Room’s Shapiro, another LowLine Board member, has also worked as a producer for the Green Apple Music Festival, the Central Park Jazz & Colors Festival and the Great GoogaMooga, all of which are privately run festivals held in public parks.

Most importantly, it will be the tone of the LowLine’s commercial space — the lease to which is, again, an essential source of revenue earmarked to cover the space’s operating costs — that will play the largest role in defining the space’s day-to-day atmosphere and use in the coming years. Even if the commercial space is kept small, its location within the LowLine’s official space will give that tenant, and ultimately the demographic they hope to attract, an incredible amount of control in defining the feel of the larger room. For a concessions lessee, even simple questions about what will be served (coffee vs. booze, panini vs. Pies and Thighs) and their operating hours will be integral in defining how the space is used and the rhythms of the visitors it caters to. Tougher questions about seating and the tenant’s popularity further complicate things. A passing familiarity with the commercial development currently roiling through the Lower East Side, or, honestly, a quick stroll down Orchard Street on any Friday evening, makes it too easy to imagine the LowLine playing host to a corny Pan-Asian Beer Garden, or serving as the waiting room for the newest location of Parm. What happens when tour buses begin dropping piles of eager tourists in the area? How is the space negotiated when the sidewalk scene rushes inside to take cover from a sudden rainstorm? Who polices the LowLine’s maximum capacity? Am I allowed to stroll the space with my margarita? These are not insignificant questions.

Private commercial leases to concession groups like the one bundled into the LowLine’s plans are common in New York parks. The Pavillion at Union Square pays the city an annual rent of three-hundred-thousand dollars to operate in the park’s northern pavilion. Midtown’s Bryant Park has been run by the non-profit Bryant Park Corporation since 1992 and is fairly credited with the surrounding area’s dramatic rejuvenation. Recently however, the BPC has faced criticism for opening the doors to unsubtle corporate sponsorship with recent projects like the Southwest Porch, an open-air bar and restaurant “celebrating” Southwest Airline’s service out of Newark and LaGuardia Airports, and the Bank Of America Winter Village, a complex of boutique-style shops, food stands, and a seventeen-thousand-square-foot ice skating rink that takes over the park every year from October through March and is sponsored by Bank of America, headquartered on the park’s northwest corner in the Bank of America Tower at “One Bryant Park.” This growing privatization of common spaces is hardly a phenomenon without precedent in New York: Damrosch Park, behind Lincoln Center, is closed for private events more often that it is open to the public and its benches and trees have been pulled out to create space for circus tents and Fashion Week runways.

From here, the LowLine’s return to Kickstarter earlier this year takes on new light. What appeared to be a scrappy but ambitious urban design project working towards creating green space in an underserved community seems to actually be quite a large and well-supported organization with close relationships to developers crashing projects into the immediate neighborhood. Over the past several years, details on the project’s space have emerged that suggest a final outcome very different from what many have come to expect. The LowLine’s proximity in location and concept to the rising Essex Crossing complex, and its financial reliance on philanthropic largess and the fees collected through events and programming, open the door to the slow erosion of the space’s commitment to public access, a type of privatization with a disappointing precedent among New York’s parks. Worse still, it seems obvious that the LowLine is being conceptualized and funded and brought into this world to satisfy the priorities of a class of residents, developers, and politicians who are inclined to measure a project’s “success” not in terms of its function as a “park” or use as a community space but along the metrics of the financial growth it generates.

If it comes to pass, the LowLine, it seems, will not be the World’s First Underground Park, but just another place in New York. A closer relative to Dorney Park than Central Park, it is an atrium, an event space, and another example of our lowered expectations for the city. On the LowLine website, Barasch and Ramsey explain that “the Lowline aims to build a new kind of public space” and it seems likely that they will be successful. That this type of place — a place which under reasonable scrutiny seems to be more of a semiotic gesture in the direction of “park” than an actual park — will be received first as park-like-innovation and then, like all innovations that ride their wave to shore, as eventually just another park, has also succeeded in cultivating a feeling of inevitability. In much the same way we have changed our expectations for who pays to build our public spaces, we have also changed our expectations for role they play in our lives. This is how you build the World’s First Underground Park.

Renderings of Essex Park Crossing by SHoP Architects

New York City, September 2, 2015

★★ The haze was starting to resemble a cheery fog, one invulnerable to sun. A woman reached through the fence around Sherman Square to pull seeds out of a withered sunflower head. The heat of the heat wave was present but somehow abstract; what registered instead was the dirtiness of the air. Only down in the subway did things truly swelter; the eight-year-old voted to hop into the air conditioning of a local train rather than waiting on the platform for an express. From the Flatiron, downtown was a gray blur, but in the other direction, the ray patterns on the fins of the spire of the Empire State Building stood out. By evening rush hour, the middle ground had sharped, but the smudginess persisted in the distance.

I'm Becoming a Slack-fingered Idiot and I Guess That's Fine

If there’s one thread running through the dozens of app updates I consent to each week, and the updates to the operating system beneath them, it’s this: it is becoming easier, over time, to get things out of my phone, and to put things into it. Various apps and services have become either more demanding or more compelling, and software and interfaces have learned how to get out of the way.

Autocorrect’s extreme assertiveness mostly eliminates friction. Gesture keyboards remove a thumb. Beyond typing, you can dictate into your phone. You can mash emoji. Much more easily, and perhaps more often, you can express yourself without language: double-tapping a photo, liking, sharing, retweeting. No time, or desire, to type? You can make a face, press a button, and hit send. You can heart a group message and leave it at that. Savvy services recognize that software is both a conduit and a bottleneck, and do whatever they can to make space and remove friction. And so our inputs and outputs increase; at least, they transfer to the phone.

This, I think, has had a strange effect on my computer use. I spend most workdays in front of a keyboard, typing into a variety of boxes: a CMS, social networks, email fields, instant message windows, group chat apps. Group chat use in particular has ballooned — I used Campfire and Hipchat in other workplaces, and with friends, but Slack has absorbed a surprising amount of utility, time and output. Chat, like instant messaging, seems to allow for a looseness not always permissible over email, where you can’t immediately jump in with elaboration. It also encourages volume. Typing into a chat is less like sending a message than jumping into a stream, or chiming in to a verbal conversation. A point is made or a purpose conveyed through a dozen short messages and responses instead of a single encompassing email. Timing matters as much as anything.

This has always been true of chat and instant messaging, and has been reflected in the new and fresh language we use on them. But now, with the similar and nearby experience of chatting and communicating on a phone, often without words, I feel a new pressure. The keyboard, which I’ve been mashing for twenty years, has begun to feel like an obstacle. After two decades of learning how to type better, I’ve started typing worse.

I don’t mean slower, or with more typos. I mean nonsense. Typgnuig like thsi. Mashging my fingers luike theyr made otu of rubber. Jsut pummlegin the keybords with al thw wrong fingers, enver even giving my hafns the time to fing the righ position.

That’s not quite representative, because by the time I’m typing something more than a few words long, I’m back in my old mode. But it’s the short responses offered quickly: starting with the hahas and the oh!s and growing into longer words, chains of words, ending, approximately, at sentence-length. A number of friends have succumbed over the least year or so. The one who gave in first is at this point basically speaking a different language, but I can understand her just fine. (The progression is: you notice it’s started; you embrace it, sort of, maybe as a joke, haha; then you realize it’s never getting better.)

Now, I’m typing and receiving fucking nightmare sentences all day. A conversation from moments ago, over IM:

Friend: can I get your read on something

Friend: as to wehther or not it’s a hoax

Me: ser

Friend: [link]

Me: either way its blood curlding

Me: i cant even tlel what im loogin at

I mean, we understood each other fine, but that was not my typing a year ago, and certainly not two. Chatting was always casual and messy but this is… drunk? Maybe I’ve just gotten lazy; it certainly gets worse when I’m tired. But I want to blame my phone, a little. Text input, in a real-time conversation, is always frustratingly slow. But my phone offers new options that are closer to the conversational laugh or grunt or smile or nod. I can acknowledge messages without responding, or communicate without speaking or typing. I can’t easily do this from my laptop, which never seemed like a problem until I could somewhere else.

One coworker is a master of the keyboard-smash — the well-placed asdofjhahsd in place of an insufficiently aghast word or enthusiastic ha. It’s vexingly vague and therefore powerful. In recent months, in private conversation, my language is lapsing into variations on keysmash constantly; it is becoming my natural state. My phone conversations have become richer and faster and cleaner; on my laptop, though, I’m becoming a slack-fingered idiot.

Anyway, either it’s the phone or I have a brain tumor. Or both! Guess we’ll find out.

Giph via Paul Ford

Some WeWorkers Are More We Than Others

by Brendan O’Connor

In late August, nearly one hundred office cleaners at WeWork locations throughout Manhattan lost their jobs after they began protesting unfair working conditions. The office cleaners were not employed directly by WeWork, a multi-national co-working startup valued at ten billion dollars; rather, they were employees of a cleaning contractor called Commercial Building Management. Such arrangements insulate employers like WeWork from having to negotiate with unionized labor, and makes organizing such workplaces difficult. The CBM cleaners at WeWork’s offices in New York were making eleven dollars an hour or less, without benefits; according to SEIU-32BJ, the service workers’ union, the prevailing wage for unionized office cleaners in New York is twenty-three dollars an hour, with full benefits.

The cleaners — some of whom had worked in the WeWork offices for three years or more — went public with their union organizing effort on June 18th. A week later, CBM told WeWork that it would be terminating its contract with the company in New York City, effective August 23rd. (CBM is still WeWork’s cleaning contractor in Boston and Washington, D.C.) At the beginning of August, WeWork announced that it was creating “approximately” one hundred new positions in the New York “community team,” referred to as Community Service Associates (CSAs) and Community Service Leads (CSLs), in anticipation of the CBM cleaners’ impending absence. Starting wages begin at fifteen dollars per hour for CSAs and eighteen dollars per hour for CSLs. All CSAs and CSLs are to receive healthcare benefits, a 401(k) plan, and equity in the company, “consistent with WeWork’s vision that every employee should have an ownership interest in WeWork.”

More than one hundred twenty cleaners were employed by CBM at WeWork’s New York locations. “We will be interviewing all CBM employees and we expect that a number of the current CBM employees will meet the qualifications for these positions and begin exciting careers with WeWork,” WeWork’s press release announcing the new jobs said. When CBM’s contract ended on August 23rd, the cleaners lost their jobs; the next day, 32BJ filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board against WeWork, charging that the company had refused to rehire “approximately 100 janitorial employees because of their support for the Union.”

(In a statement disputing the union’s account of the summer’s events, WeWork claimed, “For months we have been studying how to bring in-house various functions.” And not a moment too soon: The National Labor Relations Board, which enforces the National Labor Relations Act, ruled last week to broaden the definition of “joint employer,” rendering employers who use contract workers more accountable for their labor practices. There was much weeping and gnashing of teeth in the management-friendly press.)

August 23rd was also the last day of WeWork’s Summer Camp, a weekend in New York’s Adirondack mountains that doubles as both a company retreat for WeWork employees and a getaway for WeWork members. A New York Times piece on last year’s Summer Camp reported that the trip offered WeWorkers and their guests a respite from the same old Hamptons grind:

“I’m sick of just going to the Hamptons, with the same people doing the same things,” said Margot Vitale, 23, a merchandising assistant at Saks Fifth Avenue. She attended Summer Camp with her friend and University of Southern California sorority sister Olivia White, 23, who runs a bedding company called 41 Winks out of WeWork’s SoHo West offices. “I’m planning on meeting my husband here,” Ms. Vitale said with a laugh.

Adrian Winn, 31, was wearing tattoos on his face and body and holding Super Soakers filled with vodka and a brown Afro wig he wore on and off during Camp. “I’m getting into as much trouble as humanly possible,” said Mr. Winn, who was a co-founder of a company called Aura Social Technologies and works out of the WeWork offices on Fulton Street. “I spend my weekends in Montauk trying to get pretty girls to download my app.”

According to Instagram — I think my invitation must have gotten lost in the mail — this year, a woman wrote haiku extempore on subjects of the passerby’s choosing; there were tents in which to sleep and picnic tables at which to eat; and T.J. Miller from hit HBO comedy series Silicon Valley performed a set, as did The Weeknd. One attendee told me that he spoke to a WeWork employee who had attended Summer Camp the year prior and had so much fun that he decided to get a job at WeWork. “It was kind of like a fake music festival,” this WeWork member said. Given the ongoing labor dispute, though, he felt some ambivalence: “The whole thing rubs me the wrong way.”

This week, BuzzFeed reported that WeWork has so far only rehired fifteen cleaners formerly employed by CBM. The other positions have been filled with new workers; twenty five spots remain, for which candidates are still being interviewed. “I’m a big believer in what unions have done for this country,” WeWork President and Chief Operating Officer Artie Minson told BuzzFeed’s labor reporter Cora Lewis. “Some of my former family members were in unions.” Earlier this summer, a WeWork executive allegedly threatened to fire any cleaner who attempted to unionize, and Lewis reported that none of the six rehires she had spoken to supported unionization. A union just wouldn’t be right for WeWork (hmm), Minson said: “Independent voices among our employees go against everything we stand for as a company.” Next year, those who are hired as CSAs and CSLs will be invited to Summer Camp.

He’s not the only one: Nearly five hundred WeWork tenants have signed a petition being offered by the fired CBM workers who haven’t been hired back by WeWork. “If the hiring of these new positions changes the demographics and composition of the workers, essentially what WeWork has done is made its labor practices more digestible by saying, ‘These people are just like you, they speak the same language as you, and they receive stock benefits just like you.’ It’s a very nice package that allows a lot of people to quickly dismiss the ethical questions raised by the recent events: The immediate loss of around a hundred people’s low-wage positions,” one WeWork tenant wrote to me in an email. “It’s classic ‘there’s nothing to see here.’ It’s almost dystopian.”

In August, WeWork expanded into Brooklyn, opening up its first location in a made-up neighborhood called “Dumbo Heights,” brought to you by Jared Kushner. WeWork is also going to be the anchor tenant at a six-hundred, seventy-five-thousand square-foot space in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. “On every floor of the building there will be two kegs,” the company’s mysteriously charismatic co-founder Adam Neumann said on Bloomberg’s “Market Makers” while discussing the importance of networking over food and alcohol. “An interesting thing about our members is you will never see them abusing that,” he added. WeWork is developing the Navy Yard building in partnership with two major players in the national real estate elite. “The $380 million project,” Bloomberg Businessweek reported last month, “will be the first in Brooklyn for both Boston Properties, the largest U.S. office real estate investment trust, and Rudin, a family-owned company that’s marking its 110th year in business.” As it happens, Mort Zuckerman, the chairman and co-founder of Boston Properties, is personally invested in WeWork, and the company is developing its first “WeLive” residential apartments in New York at 110 Wall Street, which is owned by Rudin.

WeWork has been slow to release details about the WeLive project, initially developed at a WeWork-owned property outside Washington, D.C. As I understand it, WeWork wants to create an environment that anticipates and provides for anything and everything its tenants — and maybe, eventually its workers? — could possibly need: You sleep there, you eat there, and you work there. And soon, perhaps, you can play there, too: I’m told that WeWork is developing something called “WeWork Club” at its 85 Broad Street location in what was once Goldman Sachs’ office lounge. WeWork, WeClub, WeSleep — and then we do it all again tomorrow.

The Taylor Swift of the Eighties

by Jen Vafidis

During her promotional tour for 1989, Taylor Swift wouldn’t shut up about how great the eighties were. To Rolling Stone, she theorized:

What you saw happening with music was also happening in our culture, where people were just wearing whatever crazy colors they wanted to, because why not? There just seemed to be this energy about endless opportunities, endless possibilities, endless ways you could live your life.

Why not? It makes sense that the eighties could give pop stars some direction. Pick any year post-Thriller, look at the Billboard Year End chart, and count the number of songs in one year that you haven’t been able to escape since; these are the songs of lazy DJ sets, karaoke nights, college party playlists, and desperate car commercials. There’s some forgettable garbage in there too, but even it’s still played. You hear this stuff across state lines and generational chasms. The system worked.

Of course Taylor Swift would want to emulate artists who sold millions, and of course doing so means ironing out the country, idling away from the specific. As of this month, just over five million copies of 1989 have been sold in the United States; other than Drake’s latest, it’s the only album to sell over a million copies in 2015. In the pictures publicizing Swift’s 1989 tour, the glitter rompers and pyrotechnics and celebrity cameos all add up to this new “pop” Swift, one with endless opportunities, endless ways she could live her life. This is the way she’s living her life. It looks fun, if also a little disappointing.

Swift cites “Like A Prayer” in that Rolling Stone interview, but if I have to name a lasting pop star from the era who embodies Taylor’s distinguishing qualities — performatively guileless, massive ego, insistent on possibilities while staying within the lines, someone who hides parts of herself to get what she wants, i.e. your love — I can’t go with Madonna, who was more transparently provocative and ruthless. Janet had genuine rhythm; Cyndi was downtown in a way Taylor’s Tribeca is not; and Whitney was in a vocal class of her own. I don’t think I can name a woman. I might name a man. Let’s talk about George Michael.

George Michael was the most-played artist on British radio from 1984 to 2004. He beat out Elton John, even in the “Candle in the Wind ‘97” years, and Madonna, who had three more albums than Michael had in that span of time. “I’m the luckiest writer on Earth,” George said of the distinction. His first solo album Faith, released in 1987, has sold twenty-five million copies globally. He has sold more than a hundred million records worldwide, received multiple awards, become filthy rich, and so on. This is likely due to his being a very good singer with some very good songs — but it’s also due to Simon Napier-Bell and Jazz Summers, the managers of Wham!, who introduced George Michael to the world by getting him to China.

In Napier-Bell’s book, which has the comically capitalist title I’m Coming to Take You to Lunch, he describes the eighteen-month process of getting Chinese officials to agree to let Wham! become the first Western pop band to tour the country. Napier-Bell made a great pitch: If the Communist Party wanted to change its reputation and secure foreign investment, it would need to show it was open to the West, and what better way than to allow the band to perform on stage in Beijing? He beat the competition for this spot, Queen, by showing pictures of Freddie Mercury striking typically flamboyant poses. These conversations seem ludicrous, ironic, and probably exaggerated (“I fed the whole government,” Napier-Bell writes, leaning into the title). But they worked. Wham! in China was a spectacle that dominated worldwide media and made George Michael a bigger name than ever before.

It’s kind of moving to read what people in China had to say about this publicity stunt. Remember, this was only several years after the Cultural Revolution had ended. It’s like reading early accounts of the Beatles, but the quotes come from 1985. “The band members had long curly hair,” says one Chinese man who was a teenager then. “They dressed differently.” Another former teen admits: “Before that day, I had only seen a ballet performance.” “Back then,” says yet another, “if we wanted to listen to pop music with lyrics like that, we had to do that in secret.”

Every person who attended these concerts was given a cassette tape. On one side was a collection of Wham!’s hits; on the other side was a Chinese singer covering those hits with some altered lyrics. The BBC recently printed some of the Chinese version’s lyrics:

Wake me up before you go go

Compete with the sky to go high, high

Wake me up before you go go

Men fight to be first to reach the peak

Wake me up before you go go

Women are on the same journey and will not fall behind

People still have and cherish these cassettes. There’s also a concert film about this tour, but no one connected with the band likes to mention it. Partly because it’s bad, and partly because George Michael is the one who made it bad.

Foreign Skies: Wham! in China is an hour long, and you can watch it in its entirety on YouTube. The credits report that it was directed by Lindsay Anderson, the British New Wave filmmaker who gave the world Malcolm McDowell’s debut in if… and ambitiously looked into England’s national character in This Sporting Life and O Lucky Man!.”Perfection is not the aim” was one of his mantras.

Martin Lewis was the one to hire Anderson. Lewis had a knack for incongruous, lucrative pairings. In the late seventies, with John Cleese, he created The Secret Policeman’s Ball, the funnier “famous people being famous in public for charity” precursor to Live Aid. Before producing Foreign Skies, he already had experimented with putting filmmakers and pop music together by giving ten thousand dollars to Sam Peckinpah to direct two Julian Lennon music videos. (They’re fine, kind of chaste even. Peckinpah died months later, so they’re the last waltz for him.) Perhaps if Lewis were less self-aware, less British, he would write an incredible The Kid Stays in the Picture-esque aria about the last half of the twentieth century. In light of that, Anderson makes some kind of sense, in that he doesn’t make sense at all.

When Anderson showed his final cut of the film to the managers and the band, he was kicked off the project entirely. In his diaries, Anderson described the tone of his cut as “humorous-lyric-ironic,” a montage of episodes that showed the band interacting with a world they didn’t know. It was meant to appeal to an audience larger than “Wham! teenies.” George Michael hated it.

“None of this, I suppose, is exactly astonishing,” Anderson wrote coolly. “When I first took on the assignment, I warned myself not to get too involved, since such projects so often end by conflict between creators and exploiters, and in such situations the exploiters must always win.” That would have been a nice, even-keeled way to sum it up, but he went on: “I must admit, though, that I was not prepared for the incredible waste, silliness, lack of conscience, ignorance, lack of grace, lack of scruple, egoism, weakness, duplicity, and hypocrisy which have characterized the whole operation.” Bad blood, for sure. The film was cut from ninety minutes to an hour, and If You Were There (Anderson’s original title, a good one) became Foreign Skies: Wham! in China. No one is legally allowed to screen If You Were There publicly, even though it lives with Anderson’s papers at Stirling University.

“Like the trip itself, Foreign Skies is a sad, confused affair,” wrote journalist Tony Parsons. He’s not wrong. There is lots of footage of the boys walking around bazaars and interacting with ancient Chinese people, as well as several sequences of Chinese youths working out (think tai chi and martial arts, not weightlifting) while various Wham! hits play. George and Andrew stand on the Great Wall. They wear Communist Party hats and several billowing suits. Some woman in pastels at the British Embassy says Chinese food is “too rich” for her taste. One wonders what other embarrassments Anderson caught on film.

There are twelve performances in Foreign Skies (there were only four in If You Were There). One of them is Wham!’s cover of “Love Machine,” which goes on way too long. One of them is “Everything She Wants,” and another is “Wake Me Up Before You Go Go.” Of course, the last performance is a nine-minute version of “Careless Whisper,” and it is the reason the film endures beyond cultural curiosity. George Michael sings “Careless Whisper” in a white suit jacket and pants, with no shirt on underneath. We watch his glistening, orange, hairy-enough body as he holds his microphone with two hands and makes a fist to show the song’s power.

I won’t be obvious and say that all pop music traffics in artifice, but George Michael’s songs absolutely do. He’s often making a proposition to keep it all going, to keep the illusion alive. “I’ll tell you that I’m happy if you want me to,” he sings in “Everything She Wants.”* “I will be your father figure,” he promises on “Father Figure.” While it’s a mistake to read any pop song as autobiography, a remarkable amount of George Michael’s lyrics operate on closet logic: The “if, then” language and modal dance of someone who wants to keep a secret while still getting what he wants; it’s an equal exchange until someone realizes he’s not happy.

In “Careless Whisper,” more than any other song from that period, he regrets how easy it is for him to pretend this arrangement won’t fall apart. “You’re no fool,” he admits. “We’d hurt each other with the things we want to say.” And in “Freedom ‘90,” Michael sings:

I think there’s something you should know

I think it’s time I told you so

There’s something deep inside of me

There’s someone else I got to be

George Michael was only twenty-one when he wrote “Careless Whisper.” He was twenty-two in 1985, when he performed it in the Worker’s Gymnasium in Beijing in front of thousands of Chinese people who suddenly had the ability to see something like this, after decades of isolation. Five years later, George Michael would renounce this image of himself, the hairy man sniffing himself and smelling what it means to be a man. But it is powerful stuff. Masculine, sensitive, and hurting. Full of pain and guileless. Knowing, but still pretty stupid. Death in Venice could be rewritten about young George Michael. The gay-yet-still-mainstream George that came out later, via a “lewd act” in public that he has since called “subconsciously deliberate,” is something different and much less erotic: predictable.

There are some concert films we take seriously because we recognize that the people in them are artists. Crucially, Stop Making Sense and The Last Waltz both feature very few shots of the audience (while Foreign Skies is all about its audience, to the point of being defined by it); both Jonathan Demme and Martin Scorcese focus on the music, which inevitably reveals several narrative gaps: Why bother with this band, these singers, if we cannot see how they are received, how they are used? Who is the audience, besides us, and why are we there? For starters, there’s usually a connection between the filmmaker and what’s being filmed. “I loved Melvin and Howard,” David Byrne explained. “I was a Talking Heads fan from the very beginning,” Demme gushed. These filmmakers also have an authoritative language at their disposal. Bill Graham shouted at Scorcese during Dylan’s too-loud performance of “Baby Let Me Follow You Down”: “Shoot him! Shoot him! He comes from the same streets as you!” The impulse starts with the heart — maybe yours, maybe theirs — and it gets bigger, like all love affairs and forest fires.

Sometimes, when someone calls something “cinematic,” that just means it’s big. David Byrne’s iconic big suit, the gray flannel suit that Pauline Kael called “the perfect psychological fit,” was inspired by a fashion designer telling him “everything’s bigger on stage.” It’s true. Everything is bigger on stage, and even bigger on the screen. The concert film only truly works if the music is big to begin with, if it depicts a group with a lot to express. The album that preceded the China tour for Wham! was called Make It Big. George Michael, in Lindsay Anderson’s words, had an enormous ego, was bigger than everything and everyone else on stage to the point of breaking up the band he had formed with his schoolmate. It’s strange that this doesn’t lead to something bigger to behold, something beyond the Top 10.

The best concert films of the most recent era, despite not being directed by any boomer-approved luminaries, are Katy Perry: Part of Me and Justin Bieber: Never Say Never. (Taylor Swift’s concert films are both bad, not least of all the one that is a misguided collaboration with Def Leppard.) Both are in 3D. Both are thrills. In both, the costume of innocence is outgrown or burning. These films are about costumes, cultural idioms, and profit — they’re extensions of popular music in the way that music videos used to be. By way of example, in David Fincher’s glossy music video for “Freedom ‘90,” the iconic leather jacket Michael wore on the cover of Faith, also goes up in flames. It’s a script that’s now in every pop star’s hands. It’s something everyone understands.

Foreign Skies is not like these other films though, because it shows the relationship between the music and people who don’t understand it. Or they understand it differently — it’s hard to tell if they don’t get it or if they really get it, better than we do. Probably both. Ultimately, Foreign Skies is about the tension between what’s exciting (uncharted territory, Western expansion, sexual tension) and what we can’t prepare for. How could George Michael and company not anticipate what Lindsay Anderson saw so easily: This tour was an invitation to be part of a pivotal moment in China’s history. In every scene, even with all the editing, it’s hard to tell who is the exploited and who is the exploiter. Who is gaining what from this moneymaking scheme? At first, you think Wham! is the winner, hopping from city to city, having a great time in billowing shirts with new fans. But by the end, as you watch young Michael perform sexual confusion and misunderstanding for an audience who mostly can’t understand him, you’re not quite sure.

Taylor Swift is always gaining something though. Her strength is not the long-form, “uncensored” concert documentary or the music video, despite her recent VMA win; it’s the long unfurling of an album release, or her Instagram videos and her tweets, pregnant with “surprises” and gratitude. She’s always, we’re told, involved with the production. Her apparent ignorance of how she could be interpreted is reframed as intention and supported almost instantly by her collaborators. The other day, director Joseph Kahn gave a statement that explained how the video for “Wildest Dreams” was not a work depicting a colonialist vision of Africa, but a classic Hollywood romance, as if the two weren’t often the same thing. He went on to point out the number of people of color on the creative side, including himself, as well as in front of the camera (though not, of course, featured in any prominent way). The final strategic deflection came with the assurance that Taylor would be donating all proceeds from the video to the African Parks Foundation, which preserves endangered species and supports local economies. Her mistake was prepared for, if not the expectation.

George Michael wanted something like the pictures from the 1989 tour: bright explosions, celebrity fun, a star fully embodying what they want. In Taylor’s Instagrams or tweets, there is no room for the weirdness that must exist in her life as she expands, as it has to exist in any life that includes world tours. Even when she’s embarrassing, she likes to tell us that she knows how embarrassing she is. Her maturity as an artist has meant acting like she knows what we’re thinking and that she’s giving us what we want. Maybe it’s only natural.

Make it big, whatever it is.

*This piece originally listed an incorrect title for this song. We regret the error!

A Poem by Morgan Parker

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Preface to a Twenty Volume Joke Book

“And now, each night I count the stars. / And each night I get the same number.”

-Amiri Baraka, “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note”

I’m done with The Real World

Now I watch Top Chef

And dream about a life of tasting

And get so hungry I could die

I don’t root for the moon-face

Pale in his intention

I’m grown up

I’m rooting for the black girl

Cooking fried chicken for the first challenge

All my life I taste

“Whatever man I’m a black girl”

Shaking her afro

My feelings are pretty real

Sexism is pretty real

No one tells me I’m beautiful

I dream about tasting

In all my baby photos I have this

Look like oh my god

I feel sorry

I have always been terrified to be

This is just a taste

It’s not ready yet

Roll the token around on your tongue

And let it breathe back at you

I butter my skin

A curse I drink and drink

When I wake up I never think

I will be told to be ashamed

I’m not ashamed

No one tells me I’m beautiful

Sometimes Stevie Wonder makes me cry

There is a little chill in the air

I have seen everyone before

I say everyone

Is dying but that is not what I mean

Everyone is getting killed

Animals with long greedy tongues

Animals living on blue mountains

Literally my body

Shaped like a question mark

I am trying to get lower to the ground

I am trying to breathe the soil

I want to know the future

Whatever man I’m black

No one tells me I’m safe

I’m done with singing

The only songs I know are work songs

I’m grown up chained

To bad ideas and sugar

My bad ideas are pretty real

One of them is dark arms in the sea

While the sun comes up

Minus one then plus one

I don’t think anything is a mystery

I know I’m ungrateful

I know I am very hungry

I wait too long to give up

Several eclipses pass

My hands burn and peel

Everyone is corny so I’m alone

Whatever man I’m alone

Oregano leaves shrivel I’m alone

I want to know the future

is a bright violet grape

Everything has skin

Everyone tells me sorry

I know the world is dangerous

Everyone tells me sorry

I am hallelujah the first plague

My name is suitable for spitting

Please touch me

all I have

are these terrible animals

this hunger

Morgan Parker is the author of Other People’s Comfort Keeps Me Up at Night (Switchback Books, 2015). She is a Cave Canem graduate fellow and a Pushcart Prize winner. She lives in Brooklyn.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

New York City, September 1, 2015

★★ A hurtful glare filled the sky from the east. People in the bank, in the part of the bank that still used people, were talking about the air quality. An old butter-colored Impala gleamed in a lane of sun beside the shadows on 20th Street. Tiny flashbulbs went off in the sidewalk concrete. Past midday, clouds covered and uncovered the zenith. The thick warmth soaked into chilled joints. The later-day sky was clear again, admitting new heat. Cops and banjos flanked the subway entrance. The entrance hallway in the big public school was sweltering, but air conditioners made a racket in the old, hard-surfaced auditorium, under the dim blue of the lights. The three-year-old decided the tag in the t-shirt he’d been wearing all day was suddenly too much to bear, and insisted on making the walk home bare-chested.

The Hottest Bar in Philly Is on Top of a Shuttered Public School

by Andrew Thompson

In 2013, the Philadelphia school district shut Bok Technical High School, along with twenty-two other schools — nearly ten percent of the city’s public schools — to wipe out a budget deficit of nearly a billion-and-a-half dollars. Last month, Lindsey Scannapieco, the daughter of local high-rise developer Tom Scannapieco, closed a deal to purchase the building for 1.8 million dollars. The younger Scannapieco is the managing partner of Scout, which describes itself as a three-person “collective of young enthusiastic urban designers,” and is re-developing the Bok site. Its first use of the three-hundred-and-forty-thousand-square-foot building is Le Bok Fin, a “members only” pop-up gastropub on the school’s roof, which is running until September 13th.

On a recent Saturday evening, the line of people, which numbered in the dozens, snaked through the school’s ground-floor hallway back to the school’s entrance and past a door underneath the letters “BOYS GYMNASIUM,” not yet removed from the wall. Collages of old Bok yearbook photos had been erected in the hallway next to the elevator that carried diners and drinkers to the roof. (The word around town, on Yelp and Reddit and the food blogs, is that the view from the top of the Bok lives up to its claim as “Philly’s greatest new rooftop.”) One of the collages featured a black-and-white clipping of the school’s food service program: “‘Le Bok Fin’ instruction is given in the preparation of menus, buying good, calculating the…” The rest of the words were cut off. “Le Bok Fin” was the name of the school’s culinary arts program, itself a play on Le Bec Fin, a high-end restaurant that closed in 2013, the same year as Bok.

“We’ve been here since 1938,” a man in a black shirt standing next to the elevator told me while I looked at the collage.

“Were you a teacher here?” I asked, knowing one former Bok teacher that had struggled to find work after the closure.

“No, just working this,” he said. “That would have been awesome. This place used to be awesome, had all kinds of programs, like shop and metalworking and stuff.”

A photo posted by Mason (@masefacetheace) on Aug 30, 2015 at 9:29pm PDT

When it closed, Bok was both one of the last vocational-technical high schools in the School District of Philadelphia. While enrollment had suffered because of Philadelphia’s ongoing exodus — the city’s recent growth is due to new births, rather than influx — and from the growth of charter schools, which claim more than twice as many students today as eight years ago, Bok was one of the better-performing public high schools in a drastically underperforming district; Bok students had a thirty percent higher graduation rate than those at South Philadelphia High School, the nearby public school that absorbed many of its students.

A photo posted by Uwishunu Philly (@uwishunu) on Aug 30, 2015 at 3:07pm PDT

About twenty people crammed into the elevator and rode eight floors up to the roof looking out over the city’s expanse of rowhomes and its modest bell-curved skyline. Staples of the Philadelphia breed of pop-up beer garden were all there: cans of Yards and Allagash and Dogfish Head, cheese plates, beef tartare, and Paris Dogs. Atop the roof, scores of people milled about, commenting on the view and taking pictures of the skyline. Past the booth to order food and drinks, people sat underneath a gazebo in chairs taken from the classrooms below. The tiny tables had chalkboard surfaces which could be drawn on with chalk placed in chemistry beakers at each table, a nod to Bok’s science program; people played tic-tac-toe and drew pictures of cats. A larger chalkboard on the side of the booth asked, “WHAT DO YOU WANT TO SEE AT BOK?” People had written their answers underneath using the chalk from the beakers: “Gelateria,” “Café–(Lavazza),” “Green house,” “Taco truck,” “Pizzeria.” As I looked at the responses, a young blonde woman wearing a white summer dress walked up with a piece of chalk, wrote, “BB-Q Joint,” and returned to her friends.

A photo posted by Kevin (@kevinmulh) on Aug 29, 2015 at 10:59pm PDT

The building is one of the city’s artifacts from the New Deal, a structure of Deco regality built by the Works Progress Administration to house public education. According to Scout’s website, it plans to turn it into “a new and innovative center for Philadelphia creatives.” Vague, but there has been more specific talk of making Bok the largest “makerspace” (a mix of workshops, studios, and co-working options) in the city; last year, shortly after Scannapieco began the acquisition process, she told NextCity that it “has always been a space of working and learning and that’s so embedded in the structure of the building,” which is “something we’ll really honor, preserve and continue.” In March, Scout won a hundred and forty-seven thousand dollars from the Knight Foundation to turn Bok into “South Philly’s Stoop,” which will “include a community stoop, a new bus shelter for the 47 bus along 9th Street, a bike pump and repair station and a new-and-improved dog park.” Scout is currently taking leasing applications for “Building Bok.” (No one from Scout returned requests for comment on its plans for the building.)

A photo posted by Janan Rajeevikaran (@jananrajeevikaran) on Aug 29, 2015 at 7:07pm PDT

Over the course of three hours, wave after wave of people came from the elevator so that by sunset the roof teemed with what seemed like three hundred bodies. People lining the edge of the roof continued taking indistinct photos of the skyline with their smartphone. “Total sidenote, that view is so fucking beautiful,” one woman said to her friend, pausing in their conversation. There was a flag waving in the wind atop the former school’s flagpole. It was emblazoned with a graphic based on the capitals of the building’s column-like protrusions, a quintessential Deco accent of five bars in increasing and descending size, the tallest in the middle. Tote bags with the logo were available for ten dollars.

Correction: Le Bec-Fin never had a Michelin star, much less three. We regret the error!