Today's Internet Is Tomorrow's Aesthetic

Ever see a crazy-long, indecipherable reblog chain on your dashboard? Not ideal, right?

Starting tomorrow, reblogs will have a new look — one that showcases all comments as equals, not buried under an impossible stack of blockquote indents. Our change to reblog captions last month laid the necessary groundwork for us to arrive here, at a place where the dashboard will be a lot easier to read and cleaner-looking.

Remember reblogs? Those big long chains of names, and sometimes words? Remember looking at Tumblr for hours and days and months before ever quite figuring out which way the word-stairs led? Remember trying to figure out where to submit YOUR little words, and in what format, and, wait, what are people going to see when I post this, exactly? And who’s going to see it?

Remember text boxes that you would fill with text that might surprise you when it came out the other side? Remember Tumblr blog designs? Oh my god. Remember Tumblr blog designs?

Remember scrolling and THEN reading? With a mouse? Remember rubbing your touchpad down and the stuff on the screen moved up? Remember the funny cursors sometimes? Remember the ‘next’ button and the ‘previous’ button and remember not remembering which one was which?

Remember remember the 90s in 2013? Remember remember remember.

In 2018, a twelve-year-old girl finds a picture of a laptop computer with Tumblr on the screen. The post is a rotating gif of the word “memes,” set inside an old browser with a back button. The reply chain gets so skinny you can barely read it.

She nearly cracks a smile, then posts the picture to her Tumblr app without comment. 7,000 reblogs.

New York City, August 31, 2015

★★★ There was no compelling reason to look up at the dead and seemingly colorless morning sky, but there in it were pretty scalloped patterns of brightness and then some subtle blues. The haze or clouds thinned to pass a mellow tropical light. The air was not easy to breathe. Gradually the sun filtered more, to a clear sherry color. An immense running figure, in cirrus brushstrokes, stood in midstride over the west. The three-year-old’s newer and brighter light-up shoes went strobing down the deepening shadows under a scaffold, meeting the flash of a woman’s burnished gold sandals coming the other way. It was sweaty still in the gathering dusk. A man carried a stack of glowing artificial votive candles around the edge of the pierside cafe, setting them out one by one on the outdoor tables. The George Washington Bridge twinkled. Dark wavelets flickered on the pink field of the river. A slow fishy breeze cooled the pier a little. A young woman in flip-flops showed off for her friends by climbing to the top of the concrete barrier and stepping over the metal rail to pose over the now-dark water.

Stripped

by Matt Siegel

The car I’m borrowing during my visit home comes complete with tape deck and telescoping radio antennae that I broke by listening to NPR while going through the car wash. I listen to NPR constantly — not so much because of intellectual curiosity these days, but for the soothing distraction of other voices. I avoid my music because almost all of it is sad — Sharon Van Etten, Perfume Genius, Cat Power, PJ Harvey sad. Only the what-I-refer-to-as “bad bitch anthems” have the ability to momentarily snap me out of my forlornness, and I’ve overplayed Rihanna’s “Bitch Better Have My Money,” so that it no longer serves its purpose.

Driving past the STI clinic where I was tested before having bareback sex with my first love makes my sinuses throb. I am pre-cry, which is similar to pre-vomit in its emotional and physical discomfort, and in the semi-relief that comes post-purge: relieved it’s over; anxious it might happen again. He was my first real relationship: first love, first person I would do almost anything for, first one over a month long. I was his first love too, though I’m not sure what that means to him.

It should be noted that I initiated the breakup. I was being forced out of my ridiculously cheap home, and it didn’t make sense to stay in Sonoma County, engaged in the adjunct teaching struggle where I had no intentions of laying down roots. When I informed Shayne of my decision to relocate, his reaction was downright rosy: “I think it’s a good idea for you”; “I always thought you belonged in L.A. (backhanded compliment?)”; “I support you in whatever you do”; “I love you.” His cliche, preconceived notion of L.A. prevented him from even considering coming along.

The next morning at breakfast, he remained unaffected, as always. I marveled at his beauty and attempted to revel in what was left of our coupledom that I had often been flip about. Being valued romantically had enabled me to move through my days with the air of a beloved actress, with a kind of arrogance I quite enjoyed. Over an omelet, the tears began — I am not a regular crier (well, at that point I was not a regular crier) — and I hid my face behind a menu. “Aw, babe. It makes me so sad to see you cry,” he said.

A few days passed and I was noticing that Shayne seemed completely unmoved by the fact that this was ending. “I don’t see the point in wasting time dwelling in bad feelings. Don’t cry because it’s over, smile because it happened,” he said, all but quoting Dr. Seuss.

“I wish we could’ve mourned this together,” I blubbered. “I think that would’ve been most ideal for me.” That had been the plan — that he would be as distraught, if not more so, than me. That he would suggest a long-distance arrangement, which would remain in effect until it organically petered out on its own, or until I met someone new, let’s be honest. That was my plan. His plan entailed not just moving on, but moving the fuck on, and quickly.

He has a new boyfriend; I can tell they’re well suited for each other. I peeked at his boyfriend’s Facebook page (once, I’m not a masochist): He works at a farm, does yoga on the beach, takes bong hits, is tall and svelte. I saw a photo of him resting his head on my ex’s stomach. A friend commented that she “love[s] you two!” I wondered how long they had been together so that they were now a “two.” I often imagine what the two are doing on the Friday nights when I’m at home alone watching reruns of The Real Housewives of New York City on my computer, which is somehow more pathetic than watching it on the television. This particular Friday night, though, I’m on my way to a gay male strip club for the first time, and I’m not exactly sure why.

I drive and toggle between my Grindr and Scruff accounts. It’s a death wish on a few levels. I feel a certain urgency to hook up when traveling, as I have the benefit of being a new face on the grid. Not everyone is replying to my messages, so I am busy reviewing the reasons why. Number one is that they don’t like my B face. (I’m a teacher, so I’m prone to letter-grading.) Second, the profile photo I use only does a decent job of masking my femininity, which, in my experience, is a turn-off to a majority of potential suitors. I apologize to myself for the betrayal, then take comfort in the fact that it will not matter how I look at the strip club. I don’t have to feign confidence or masculinity; I can waltz in with my purse on my sad slumped shoulder and these men will act attracted to me.

It’s 10 PM and the parking lot at the strip club lot is nearly full. I park next to a pedophile van — a white Chevy G20 — complete with curtains. On the way up the ramp to the club, there’s a NO FIREARMS ON PREMISES sign on the wall. A duplicate of the sign is posted front and center on the main door. I assume this has been a problem in the past. A surly-looking heavyset bearded man, who is every surly-looking heavyset bearded man, sits smoking at a receptionist’s desk. The over air-conditioned room combined with the cigarette stench reminds me of any casino. There are no double doors blocking you from the action until you pay the ten-dollar entry fee — just look to your right and there it is: the I-shaped stage with four dancers peacocking, most of the tables around the stage full of patrons. Dancers? Strippers? I don’t know exactly what to call them, but several are walking around shirtless with armbands — their piggy banks — on each bicep.

I go to the bar and order a greyhound with Ketel One. “It is real Ketel, isn’t it?” I smile, only half-serious in my snobbishness. “Promise me you’re not filling a Ketel bottle with well vodka.” The bartender laughs and assures me it’s real. He hands me a large plastic cup with the concoction. “Let’s give it up for Aspen, Tyson, Russ, and Trent!” orders an invisible Ryan Seacrest over the loudspeaker.

I’m sitting on the sidelines sipping my greyhound through a straw and taking in the room. I dread the way my clothes will smell later, but am enjoying the scene: The clientele appears diverse; no single ethnicity dominates, which is indicative, I think, of the club’s location in a major city where approximately thirty-eight percent of the population is white, fifty-four percent is black, and eight percent is classified as “other.” The dancers — no, you know what, I’m calling them strippers — are also seemingly a refreshing mix. Their bodies meet general societal standards of what is hot, but I tend to wonder about the guy with a six, seven, or eight pack — and those V muscles, the “dick muscles” that point downward toward the penis. How narcissistic do you have to be to put that much time into sculpting your body? My ex had a four, five, or six pack (I never counted) from avid cycling — a side effect of sport, that makes sense to me — but when your goal is this cheesy representation of extreme maleness, well, count me out. That said, I wouldn’t mind snapping my fingers and possessing toned arms and legs in homage to Tina Turner.

A few strippers are giving naked lap dances. It’s just bizarre to watch the dorky middle-aged man in the red button-down shirt in front of me engaging in what is essentially frottage with a naked stripper in plain sight. The room is loud, full of revelers, and here he is out in the open, in the throes of ecstasy. The stripper is nuzzling his face into his client’s neck; they are grinding into each other. The stripper pauses and holds the man’s face, looks earnestly into his eyes, and says something to him with the expression I felt come across my face the time I told my ex how glorious it was that we were best friends and lovers. They’re planning something — either a visit to the VIP lounge, or an empty promise from the dancer of an outside date.

This is a gay male strip club. Bachelorette parties are prohibited; women can only enter with a male. A woman approaches a stripper on stage, places money in his armband, then rubs her breasts against his bare dick. “This is a dick-on-dick club,” Fauxcrest shouts over the loudspeaker, “not a dick-on-tits club, ladies. Nobody wants to see that.”

One stripper currently on stage is playing with his cock in the least sexy way — like a child stretching it, cartooning it. Apparently he’s the funny one, the Lucille Ball of the bunch. He goes from penis balloon animals to pulling his cock back between his legs so that it looks like a vagina whilst giving knowing winks to audience members. I kind of want to yank him off the stage and remind him that “this isn’t the drama club” as my seventh-grade soccer coach scolded me when, in a rare moment of making contact with the ball, I was simultaneously kiki-ing with my girlfriends on the sidelines. He should be up there doing that stupid dance that male strippers do when they’re trying to dance in a sexy masculine way while wearing only underwear, socks and tennis shoes. Yeah, he should be doing that dance. Perhaps he is so confident in his looks and masculinity that even the appearance of a faux vagina won’t hurt his sales.

Another stripper on stage is quite effeminate, with a gorgeous twink face. He has one of those offensive “onion” hairdos — shaved on all sides except for a ponytail atop his head. His face is lovely, though, and he — he is a dancer. He stretches lithely against the pole; he pirouettes; when one female patron brings him cash, he drops into a split to accept the tip. He’s working. I wonder if his effeminacy impedes his earnings. I have to think it does, or perhaps I’m projecting.

One short, scrawny stripper is making rounds. He’s more my type, so I approach him. “You have a good thing going,” I tell him; Calvin’s his name. “You’re niche.” He looks at me, confused. “Do you know what I mean by ‘niche’?” I’m aware of the unintentional condescension in the question, so I say it in the least condescending way possible, like when I carefully correct my students so as not to crush them. “It’s like having something that nobody else has that you can capitalize on.” I continue, “You’re shorter and…more petite than the others. I happen to prefer your body.”

Silence.

“And I’m sure you have lots of return clients that do as well.”

Silence.

I change the subject to pricing because I want to know if it’s in the cards for me to go to the VIP Lounge and maybe even get a private dance ([singing to myself] a dance for money, do what you want me to do). One hundred and forty dollars for fifteen minutes in a private room, he tells me.

“Fifteen minutes?!” I balk. “At that rate, I better come.” I know that, for whatever reason, ejaculation is technically against the rules here. “So, does that ever happen?”

“I’m sure it does,” he says slyly.

“What about the strippers? Do they ever come?”

“I’m sure they do,” he says.

“Well,” I say, “I just can’t in good conscience spend that much money.”

He says nothing.

“I mean, that’s a lot to pay when I can have sex with hot guys for free.”

Unwilling to budge on the price, Calvin says he needs to continue making his rounds and leaves.

A dandy who appears to be in his early seventies — dressed in khakis secured by belt, a carefully tucked oxford shirt, and wearing Dominique Dunne-type eyeglasses — walks past me, arm-in-arm with a stripper, towards the VIP Lounge entrance. They seem like old friends, or an affectionate grandfather and grandson. What goes on back there that could be worth paying an additional ten dollars? Nothing intriguing is going to happen for ten dollars. Raise it to twenty-five and guarantee everyone a blowjob and I’m game.

“Give it up for Miller, Tristan, Tyler, and Brendan,” Seacrest calls out. These names.

A stripper next to me playfully sticks his tongue out at a clique of his colleagues who are all puffing on e-cigarettes. Their jobs don’t seem so bad, actually. The atmosphere here is upbeat and fun, not dark and hypersexual. The sexual seriousness that one would find in your average gay sex club is diminished because getting off is not the goal unless you’ve got one or two Benjamins to drop. This is an interactive good time with a live show and strippers flirting with you in hopes of coercing you into at least a solo dance. I’d love to come here with friends and get drunk and smoke blunts and be ballers.

A divine-faced stripper sneaks up behind me. “You’re on Grindr,” he says, glancing at my phone. “You must be horny.”

“I’m really just perusing,” I say.

“Seems like most people on there do that.”

“Oh, I fuck,” I assure him. “I usually fuck.”

He introduces himself as Vince and asks my name.

“Guess,” I say, playing the coy vixen.

“Sir Licks-A-Lot,” he replies. I pretend to think it’s funny.

“Might I interest you in a solo dance?” he asks. A solo dance consists of a naked stripper humping the patron in a variety of ways. A patron is not supposed to touch the stripper’s penis, and the patron’s genitals cannot be exposed. It takes place out in the open, costs twenty dollars, and lasts the length of a song.

“Are we talking an extended dance remix or a radio edit?” I ask. Each song is somewhere between three and five minutes, he says. Again, I repeat the sentiment that at that rate I want to come.

“I would make you wet.”

“Make me wet?” I reply. “In my vagina? I don’t think I can get wet.”

“I like missionary position,” he continues. “I’ll put you on your back.”

He’s puffing on an e-cigarette as I conjure an image of what this act would look like to the other patrons.

“What flavor is that e-cig?” I ask.

“Milk,” he says. “It tastes like milk and cereal.” He offers me a puff. It’s sweet and gross.

Vince suggests that we go to the VIP Lounge where there are fewer people. I say that I’ll go, but that I’m not agreeing to a solo dance. On our way, he tells me that ninety-five percent of the strippers are straight. “A lot of them will do movies (porn) and some clients will fly them out to places like California (escort).” I don’t buy his ninety-five percent heterosexual statistic; I suspect that for unfortunate sociological reasons, the same reasons why I feel I need that ambiguous Grindr photo, the fantasy that these men are straight is appealing to the patrons and therefore more profitable.

The VIP Lounge is less populated than the main room and has its own stage and bar. Vince plops me down on one of those black leather couches you find in young bachelors’ apartments. He’s positioned himself in between my legs wearing only underwear and is rubbing his dick on me. In the VIP Lounge, he tells me, you can get away with touching the stripper’s dick. Apparently that extra ten dollars is a dick-touching service fee.

“Let me show you how big this black dick can get,” he says, waving his junk from side to side in front of my face like a hypnotist. I’m blushing and giggling and looking in other directions hoping that he will get off of me.

“So, which one of those guys do you like the least?” I say, changing the subject to the three strippers chatting nearby.

“I like that one on the right, don’t really know the one in the middle, and I don’t like the dude on the left.”

“Is he a prick?” I ask. I’m more interested in workplace gossip than I am in being molested.

“Yeah, he’s cocky as hell and just an asshole.”

Vince pulls me even closer to him by my spread legs while I’m still trying my best to desexualize the interaction via chitchat. In my direction, I hear someone say, “What you doing there, Mandingo?” I look to my left and I see the stripper who Vince dislikes, who appears to be white, waiting for Vince’s response.

“What?” I snap, glaring and scowling. “You don’t say shit like that. Go to college.”

“What the fuck?” the stripper says to his colleagues and me. He’s pissed.

“I had your back,” I say to Vince while sitting up. “Did you see that? You shouldn’t allow him to call you that.”

“Go to college,” the stripper repeats imitating me in a fey voice. I’m reminded of what I sound like and how it hinders me with other men and it stings. In this moment especially, I long for my ex who, as hot and butch as he was, loved me as I am. I fear for my future with men.

I might have accidentally tapped into the trope of the mal-educated stripper from a small rural town who had no access to good education so that he’s led to this profession. I have no idea why telling him to go to college was my go-to. What’s more, I’m not even completely sure if it offended Vince. What if it is an accepted inside joke between the two? Perhaps I should’ve stayed out of it. Having managed to cause a mini-scene, I thank Vince and make my way to the bar.

Patrons are lined up on a row of stools receiving solo dances. A man beside me nearly falls off of his stool from the intense writhing and gyrating going on between him and the naked stripper who must be forty years his junior. I watch his stripper’s face. When he’s not facing his client, he looks positively bored and disinterested. I acknowledge that there might be a day, maybe ten or twenty or thirty years from now, where I will pay to have a young fit man with a not-so-great face wriggle on me and let me touch his penis for the duration of one song.

A stripper who introduces himself as Hollywood (there must be one Hollywood in every strip club) sidles up next to me. Perhaps the name was bestowed upon him because he slightly resembles an acne-scarred Matt Damon. I ask if he’s straight. He says he’s “recently bi” since working here and leaving the warehouse where his job entailed “shipping shit out.”

“Me and another dancer make out after work,” he says proudly.

Among many gay men, there is a perceived implicit masculinity in the bisexual man that will work to Hollywood’s advantage. The bisexual hasn’t fully crossed over yet. He is still man enough to enjoy having sex with women. I remember when my ex told me how much he liked “eating pussy.” It made me jealous and turned me on.

He’s brushing his leg against mine and doing a tip-top job seeming enthralled by me. If we were on a date, I would think he wanted to fuck me. I allow myself an irrational mini-fantasy that he will fall for me — after all, my ex did. The mini-fantasy dies as soon as Hollywood asks me to purchase a dance with him. I go into my I-don’t-have-to-pay-just-to-touch-a-dick spiel and I wonder if he believes me. Do I appear to be someone who has to pay simply to touch a penis? Please, God, no. I’m thirty-three and I have a respectable Body Mass Index.

“It’s just a dick,” I tell him. “I can touch hot dick any old time. I can touch it for free.” I had hot dick for a year and a half. It was at my disposal. I loved hot dick. Well, what I loved, who I loved, was Shayne. I no longer have hot dick or Shayne and it pains me more than any Sharon Van Etten ballad on my playlist can express.

I encourage Hollywood to go find some moneyed man so that he can get paid.

“Well, you can’t judge a book by its cover,” he says shrugging his shoulders. I suppose he means that even in my t-shirt, jean shorts, and sandals, and with my adjunct professor’s salary, I look moneyed. Perhaps I have an average-looking patrician face. That’s fine with me as long as I don’t look like someone who has to pay to touch a dick.

“Can you at least buy me a drink?” he asks.

I feel my expression switch from apathetic to annoyed. He sees this.

“…or just a shot?”

“Why?” I ask flatly.

“Well, I came over here and talked to you and you don’t want a dance,” he whines.

“I was fine here by myself. I didn’t need anyone to chat with.”

“I’m sorry to make you mad,” he says and disappears. He wasn’t entitled to a reward for interacting with me, right? I certainly don’t have to pay to chat with someone. But perhaps he has such a good hustle, one that provided me with a mini-fantasy of connection, that, in the moment, I lost sight of the fact that these men are like used car salesmen of body and intimacy. I wasted his time and time is money and, as Rihanna says, “bitch better have my money.” I suppose I did unwittingly owe him a drink.

Another stripper approaches me. His name is also Calvin, and he is also short like the other Calvin. I guess Calvin no. 1 is not so niche after all. I ask him about the gay/straight ratio of the strippers. “I’d say sixty percent are straight,” he tells me. That sounds more like it. He wants to know if I’d like a solo dance. The spiel. I sigh.

“But it’s not necessarily that you have to pay for it — it’s about the experience,” he tells me. That resonates with me.

I close my eyes as Calvin #2 is squirming on me. I’m not going to achieve horniness in front of all these people and I don’t want to see them watching me. His touch — and anyone’s touch over the past year — evokes Shayne. He would do well as a stripper here: that A face, that A body. The new boyfriend with his A- face and A body — he would also take home decent cash. Me, with my B face and B body, I wouldn’t fare so well.

“Give it up for Riley, Hunter, Baker, and Rhys!” Seacrest demands as I slink out of the club, dejected, imagining Shayne and his new love in a variety of pleasant situations. I have no messages waiting for me on Grindr or Scruff. On the way home, NPR plays in the background. All I can think to do is get in bed and watch reruns of The Real Housewives of New York City on my computer.

Photo by Vito Fun

Ultra-Orthodox Internet

by The Awl

In the future, the great internet rally of 2012 might be seen as the prescient start of a global movement to grapple with the impact of this amazing and beguiling series of tubes. Addiction, distraction, stupidity and the erosion of privacy and intimacy have already been identified as some of the web’s deleterious effects. But to the 5,0000 ultra-Orthodox Jews who came to New Yorks Citi Field last month on the urgings of their rabbis and yeshivas, the problem had a rare urgency. All these effects make the Web unkosher for a community steeped in piety and tradition (one in which television is already mostly prohibited).

The internet is clearly a force to be wrestled with or at least to kvetch about.

Frozen Dinners Are Just Molecular Gastronomy for the Common Man

“There’s been a lot of baggage in this industry with consumers thinking we use a lot of preservatives,” said Rob McCutcheon, president of ConAgra’s frozen business. “But we usually don’t need to add preservatives to our frozen products, because freezing is like nature’s pause button.”

…

Products like Luvo’s are helping reinvigorate a category that still generates a handsome piece of grocery store sales. Frozen foods accounted for more than 6 percent of $810.8 billion in sales in the 52 weeks that ended June 27, according to Nielsen — or more than four times the revenue generated by the deli department.

…

“When you think about millennials who are just learning how to cook, building that skill set, frozen foods are perfect for them,” said Bob Nolan, senior vice president for insights and analytics at ConAgra.

The factory-to-table food movement continues to sweep the nation.

Photo by Daniel Oines

New York City, August 30, 2015

★★★ The act of applying sunscreen brought on the consciousness of having to do it again tomorrow, the future obligation draped over the present one. The balance bike went wobbling past or disconcertingly tangent to a drying spray of vomit chunks on a grate, a fresh trickle of dog urine, baked patches of once-runny dogshit raked with finger marks. The hot dog place was uncrowded. The afternoon grew less and less inviting-looking as the blue leached from the sky, but with that the sun’s heat faded too, till there was nothing wrong with being out in it.

The Rise of Armchair Marketing

Here is something worth staring in the face:

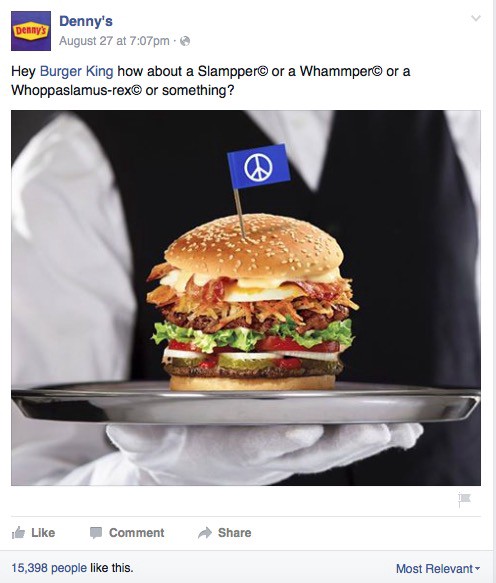

Burger King sent McDonald’s an open letter proposing that the two fast food chains team up to create a hybrid “McWhopper” burger to celebrate Peace Day on September 21st. Burger King suggested that the “ceasefire” would take place at a single pop-up shop halfway between the corporations’ headquarters, with all proceeds going to the Peace One Day charity.

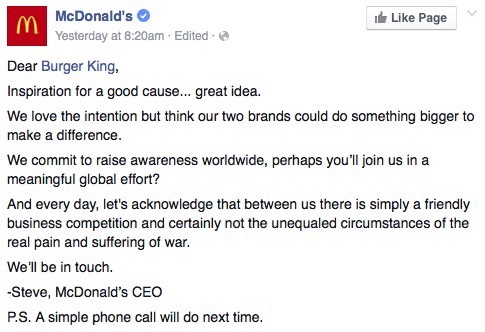

Burger King’s marketing campaign included a video, some social media posts, a special website and full-page ads in the New York Times and Chicago Tribune. In response, McDonald’s posted this on Facebook:

The campaign took the work of “seven agencies,” including David, which helped Burger King create its “Gay Pride Whopper” campaign. (Someone who worked on that project described the process to me, shortly after the ads ran and between drinks at a party so maybe not precisely, as a difficult fight against extensive market research suggesting many of Burger King’s customers would be unhappy with the concept. A large contingent within the company agreed, but were eventually overruled by the company’s fairly new and unusually young CEO, who insisted he saw a major advertising opportunity. Anyway!)

The campaign seems to have been successful in at least one way. It garnered lots of media coverage, most of which adhered to the spirit of the campaign — jokey, but not too jokey, because there’s a charity involved — and which inherited its legitimizing verbs. “McDonald’s politely declines Burger King’s offer of world peace” is the title of the story quoted at the beginning of this post.

Major brands interact, publications produce coverage. Strange? Like basically everything, sure, if you think about it. Unusual? Not at all. It doesn’t demand much of an explanation beyond “these types of things normally do pretty well on Facebook” or “people are going to be talking about this anyway, so we should post about it.”

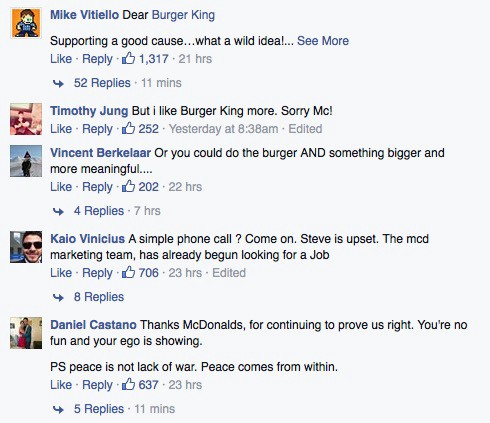

What publications might be missing, however, is just how people are talking about it. The top comments below the McDonald’s post are interesting. They’re not about the stunt, or even about McDonald’s or Burger King.

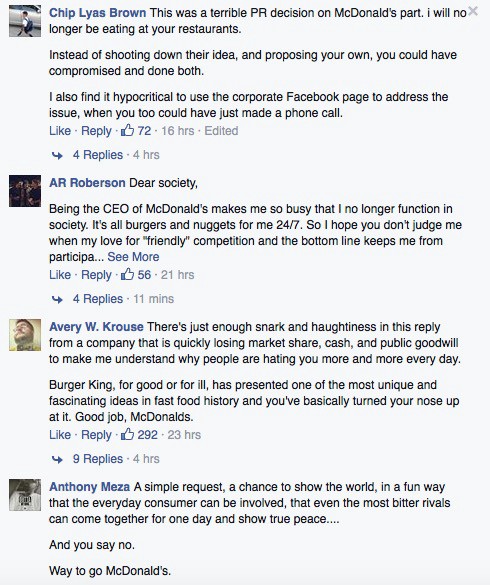

Some more:

And:

Most notable is the amount of scorekeeping going on: many of the highest-voted comments are criticizing not only McDonald’s as a brand but the company’s brand strategy — these actions are being received earnestly but with a full and demonstrated awareness of their execution as marketing. It’s armchair brand management, expressing interest and concern not just in the company or its products or its marketing, but in the optics of its marketing.

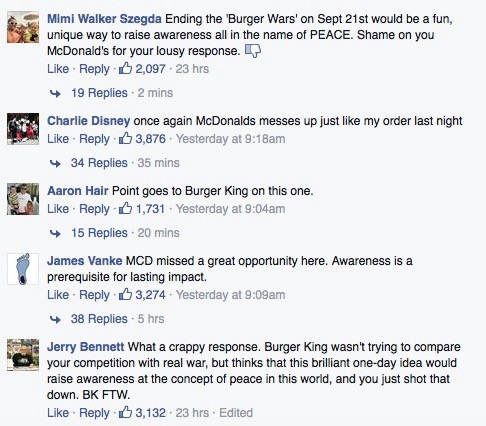

Denny’s joined over the weekend:

This is a brand dream — a vision of a future in which they are dramatically empowered, at least in comparison to the publications they used to depend on for coverage — and a transitional demonstration. Burger King’s placement of an ad in the New York Times led to countless articles in publications, which reached — largely through social media — a great but difficult-to-quantify number of fans, whose reactions would be influenced in part the source of the story; its simultaneous posts on Facebook, which used the Times ad as a mere prop, garnered huge and direct interaction, and ultimately set the venue for the response from McDonald’s. Which prong of this campaign do you think is going to come up in more meetings this year?

That the comments they produced are jarringly straightforward is a triumph of context, and a testament to the power of simplified, streamlined consumption that a front-to-back, top-to-bottom managed system like Facebook can provide. The irritated or confused or cynical comments we might be accustomed to seeing under a typical #brandwar story, even on Facebook, might just be attributable to messiness and noise — people reacting to coverage and aggregation and links rather than to the matter at hand, because they’re seeing something that, really, they don’t much want to see, or they’re seeing something they wanted to see delivered indirectly by an inexplicable middleman with a chip on its shoulder.

Here were have a much simpler hierarchy, and one within which publications — the ones that would have previously noted and recorded brand interactions with, at best, a slight gesture of antagonism — would just be getting in the way, and so are marginalized: Brands, which are verified, are performing on a special stage alongside celebrities and politicians, who are also verified, to an increasingly well-sorted unverified audience that is ready to cheer them on or tear them down within boundaries established by the platform on which they’re engaging. It’s Facebook’s intentional design and structure of authority expressed through human behavior, and it’s translating startlingly well.

In conclusion, congratulations to all brands, forever.

We Are Not Your Friends

by Jia Tolentino

We Are Your Friends, the Zac Efron EDM movie, had one of the worst wide-release opening weekends in history. Bringing in only 1.8 million dollars, it made only four-and-a-half times what Calvin Harris will reportedly make per night at Hakkasan in Las Vegas. It made four hundred thousand dollars less in its debut moment than All Dogs Go To Heaven 2.

This excessive tanking is theoretically unexpected: Efron is bankable (you saw Neighbors, right?); the procedural arts-striver movie (Center Stage, Pitch Perfect, etc.) is an evergreen format; and EDM as an industry is worth a global 6.9 billion dollars a year. But in practice, it makes perfect sense. We Are Your Friends is only good inasmuch as it’s willing to be uncomfortable and embarrassing and existentially complicated, three things that go exactly counter to what a teen who would pay to hear EDM music — which is to say this movie’s target demographic — wants.

I heard “We Are Your Friends” live for the first time the summer I was eighteen, on the first night I was in a new city. I flew to London, dropped my bags in a dorm room, wandered out of Regent’s Park, called my London-born college best friend from a pay phone on a corner, then immediately met him at a club. Justice was playing, he told me. I arrived at the Mean Fiddler in flats and cotton. “You must be American,” the coat check girl said. The lights went out; a solid cross at the front of the stage blazed white. Justice tossed neon miniatures into the audience and lit the place up.

I only knew “D.A.N.C.E.” and “We Are Your Friends,” Justice’s club-hymn rework of Simian’s one perfect UK-indie chorus. But the night percolated and pounded anyway — a painful, blissed-out, steady zonking that built to the chemical explosion of that drop. I remember it so clearly partly because I taped the night with a heavy, mom-like video camera, which I carried around all summer to fulfill the “research” requirement that put me up in London for free. I lost the tape a long time ago, but I used to re-watch it: my friend’s giddy face in the strobe lights, the baby crosses churning up and down in the dark.

It was 2007, anyway, and I was a beer-soaked sponge with my brain off. I knew what I liked, but not why I liked it or how it was made. It’s funny now, reading the Guardian review of the show that night:

It’s clear Justice are still on a learning curve: the duo DJ prolifically, but have only played live — the full knob-twiddling, keyboard-playing experience — a handful of times, and it takes several songs for their stern concentration to relax.

It hardly matters; by the time they leave the stage, […] it is likely the evening will go down in Gaspard Augé and Xavier de Rosnay’s personal history as a resounding success.

When they played those first live gigs in London in summer 2007, Auge and de Rosnay were closer to the age of Zac Efron’s rookie DJ character, Cole Carter. Today, they’re in their mid-thirties, in the presumed demographic of James Reed, the movie’s veteran DJ (played with intense cocaine alertness by American Beauty creeper Wes Bentley), as well Max from Catfish, who co-wrote the movie with Meaghan Oppenheimer. And, more than a decade after making “We Are Your Friends” — they released it as a one-off in 2003 — you wonder how Justice feels about We Are Your Friends.

The duo’s allegedly off recording their third album somewhere, and they haven’t been badgered successfully for promotional purposes, but in 2012 they told UK GQ:

One of the principles we have is that there is no weird place to hear our music: even if it’s a s*** movie it’s cool because it’s meant that for a music supervisor, your song complements this emotion or something a bit epic.

“For example,” added Xavier de Rosnay, “the best place for us to listen to our music is when there’s a football game announcement. You think, ‘Wow, if this track is powerful enough that someone thinks it could fit with a football game, then it’s perfect.’” Well, yes, they left out the part where they get sync money, but sure!

This stance wasn’t really a changed one — in 2007, de Rosnay was already telling the Voice that “We Are Your Friends” didn’t belong to them — but presumably it tilts a little differently around a flop. We Are Your Friends may have a strong second life as a hangover classic, but it will not stand up anywhere near as independently as the song that gives it its name. The two entities have opposing relationships to commercial integrity, anyway: Justice came from the aesthetic left and industry under; in not being fussed about integrity, they gained something close to it. The movie, on the other hand, was released in over 2000 theaters and stars an actor who still carries a whiff of Disney Original Movie. It comes from a paid, conservative, safer vantage point; yet it’s extremely fussed about integrity, and consequently loses its hold.

What is surprising, and presumably off-putting to the EDM teens, is that the movie admits this explicitly. True to its subject, there’s a point at which a big budget means that a certain degree of integrity’s already been fucked, and the inevitability of degradation — twinned with the futility of ambition — drives We Are Your Friends’s plot. The movie actually signals this immediately by placing Justice’s track right at the beginning. I’d expected to hear “We Are Your Friends” at the end, with Efron kissing the “Blurred Lines” girl corpo-budget as fireworks pummeled the sky. Instead, the track appears over a scene where Cole Carter’s deadbeat foursome is handing out paper flyers to promote a dance party at some Silverlake club. Nothing bad had happened yet; the subplots with unknown powders and real estate swindles had not even suggested themselves. And still, as the raucous persistent anthem faded out with the sunset over some anonymous state school, I thought, shit: This whole thing, emotionally, this whole thing in general, is a hundred percent headed downhill.

I was expecting We Are Your Friends to be a satirical, self-parodic caper (The Hangover set at EDM Jesus Camp) or an earnest, cheesy strobe-and-confetti set piece. Jarringly, it is neither. For a movie with a very uncomplicated scenario — “young DJ meets old DJ, falls for old DJ’s girlfriend, and everyone must deal” — We Are Your Friends is incredibly slippery. For one, the line between aspirational and pathetic is almost nonexistent, which is much to the movie’s credit. We Are Your Friends is decently true to its audience and subject matter — the music (Kygo, Years and Years) is right, as are the clothes, and the unfocused aggressive aimlessness, and the drug dependence, and on and on — that crucial ambivalence, which is painted over by the scene’s real-life participants to a degree that will prevent many of them from enjoying the movie, is accurate most of all.

Equally surprising is the way the movie refuses humor. Skewering EDM in 2015 would be incredibly easy, and the movie is very, very funny, but it’s laugh-at, not laugh-with. Instead, We Are Your Friends prioritizes a barbed, strange sincerity. It’s herbily didactic about the premise that Music Is A Complicated Art Form (the dialogue in this arena is horrendous; wait till the part where Efron discovers that you can make music on a computer while also using instruments other than a computer). It’s also quite clear on the fact that, if one were to be in pursuit of any grand noble ideals whatsoever, setting “EDM DJ in Los Angeles” as your end goal is really not the move.

It’s dark, is what I’m saying. The movie’s structured like a comedy, but no one is having fun. They are in constant pursuit of fun, but they can’t get on top of it, or recognize it, or are too drugged out to remember. The only moment of tangible good emotion comes directly from festival molly; otherwise, everyone’s too nervous, too sure that there’s something better, always on their way up or down. They’re choked with entitlement and dissatisfaction, the LA signature that defines Cole Carter’s posse: four demanding, lazy hustlers always gunning for a break. Distinctly white in the tenor of their aggression, these guys know it’s gonna be better; they’re gonna be famous; if you say otherwise, they’ll knock you out. It’s not very gritty and it’s certainly not cute either. Except: Everything is cute on Efron, who inhabits this part with a quiet, yearning magnetism. And the movie’s characters are as attracted to him as you’ll be during the shower sequences: The older DJ takes to him; the older DJ’s assistant-slash-girlfriend does too.

Not that the latter really “verbs” much of anything. Just like in the “Blurred Lines” video, Emily Ratajkowsi exists here as a sort of movable set piece: a blank forehead, a plumped-up top lip, a body tailored for slow-mo. But, tasked with meeting the dubiously sentient standard of a Hills person-shape, Ratajkowski does just fine; the range required is minimal. She “falls for” Cole Carter in the same way that she might Instagram a particularly appealing fern. Otherwise, naturally, the women in the movie don’t speak. One other gets a name; the rest get banged in a photo booth or vocal-fry their requests for “Drunk in Love.”

In place of the final scene where I’d expected Justice, there is something much stranger. It’s aggressively something. It’s the culmination of a sequence so earnest that I almost had a panic attack, and it feels like a combination of summit and nadir not just for Efron’s character but also the movie and also for me. Over his brand-new Track of Dreams comes Ratajkowski’s voicemail murmur from a bygone festival, dreamy under the influence: “I love it here.” Then comes a friend’s voice, recorded in a vulnerable moment: “Are we gonna be better than this?” Efron howls it into the mic, unbearably emotional, and the movie seems to be saying both “KEEP GOING FOR IT, YOU DREAMERS” and also “DEFINITIVELY NO.”

I thought about eight summers ago, my teenage self landing in London and going straight to see Justice. At the time, I was fresh off twelve years in a mega-church school, a few summers tilting old morality around a new series of wants. The through line between the club and the church service was, absolutely, salvation, which in both cases was found in a dark room, hands up, sweat, catharsis. I loved it there. And I didn’t ever ask myself if I was gonna be better than this. That’s the whole point of EDM and its less broad cousins: It’s atemporal; it collapses you away from thought into the very physical now.

I learned that and was baptized into the all-curious and anti-curious Ed Banger religion in front of “We Are Your Friends” and a neon cross. Justice, with † as their actual album title, gave me the a complete symbolic synthesis, as well as a distortion of my character and priorities whose effects I have yet to really see. The club makes you superficial and anhedonic: I know that much of what I mistook to be transcendent was in fact ordinary, or something even grosser — I also know that I’m still weak for it, that sense of ambient razored promise, show after show after show.

We Are Your Friends feels simultaneously like a Levi’s television ad, a Faint lyric video, a TED talk about BPM, and a meth-dabbling cousin of The Beach. It’s a true movie for late summer, the season of second chances, of trying to get serious, of asking, how dark is it actually all getting? The movie asks, and can’t answer. And no one can answer. No one wants to even be there for the asking. Do you know what I mean?