New York City, August 17, 2016

★★★ Loosely gathered white clouds held off the sun at first, but as soon as the light got through, it began squeezing out sweat. The air was drier, and some of the smells on it were sweet. By afternoon, the light and the breeze on the crosstown blocks were unquestionably shading toward autumn. In the middle of the uptown blocks, where the air wasn’t circulating, it was still summer. Soft silvery highlights made the late clouds lovely if you looked at them.

The Gait Debaters

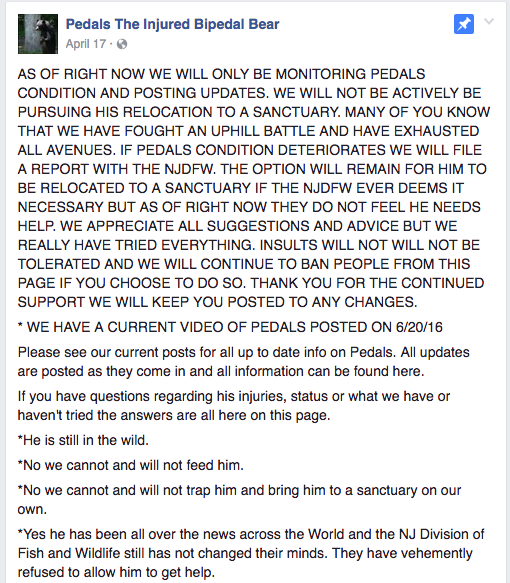

A lot of people are worried about this bear walking on its hind legs

In the wilds of Oak Ridge, New Jersey, there lives a bear named Pedals, nicknamed for his upright stance (important question: is it pronounced “peedles” after “bipedal” or “peddle” after he looks like he might be riding a bicycle?). Pedals has been spotted various times over the past few years, perambulating like a person.

With two maimed front legs, Pedals, an American black bear who displays remarkably good posture, manages to get around on his hind legs. His unusual condition has spawned coveted sightings and viral videos. “Pedals is my spirit animal,” one person wrote on Facebook.

Today, the New York Times asked if he was suffering or thriving, to which I would counter-ask, Are the two really mutually exclusive?

Debate in New Jersey: Is Bear That Walks Upright Suffering, or Thriving?

Some of the more cautious animal people argue that pedals is obviously injured or sick or deformed and this is not normal, and people should stop laughing because he needs our help. They want to send him to a sanctuary where he can trundle around on two legs in peace. One wildlife biologist wondered if his paw wasn’t mangled by a car accident, while others wonder if it’s a congenital defect.

Pedals, you’re doing great, my friend. Stay out in the wilderness, don’t come any closer to the internet. It’s too crazy for you here.

The Bodies Below the Bar

Money trouble and dwindling membership have plagued the American Legion

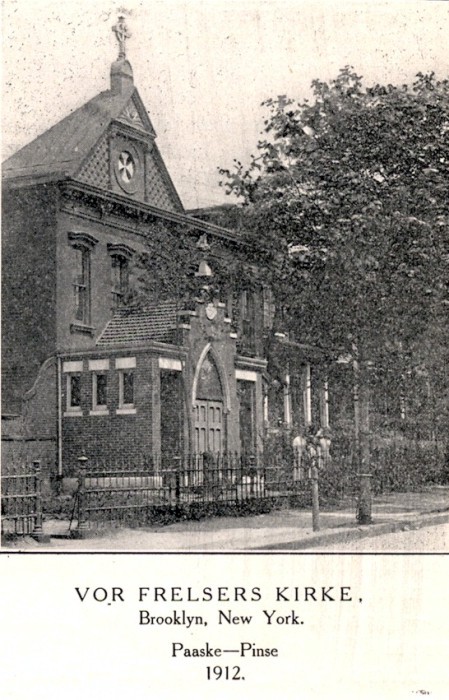

If there’s a bar that should be haunted it’s the Michael A. Rawley Jr. American Legion Post. It sits just above the corner of 9th Street and 3rd Avenue in Brooklyn, an unassuming brick building sandwiched between an Enterprise dealership and a vacant lot. The interior looks a little bit like a barn, albeit a barn with video poker machines. The bar itself is long and sometimes uncomfortably bright since the Christmas lights that hung over the drop ceiling went out and the walls are lined with plaques listing past commanders and departed members. I was hired there about a year and a half ago to tend bar part-time, basically out of pity. The place I’d been working closed down unexpectedly right before Christmas and many of the post’s members knew me from another now-defunct dive bar I’d worked at nearby.

Built in the 1860s as a Danish Evangelical Church, the post sits above an unmarked grave that stretches along 3rd Avenue — the alleged burial ground of the 1st Maryland Regiment. On August 27th, 1776, four hundred soldiers held off the entirety of the British Army in order for George Washington to make his escape during the Battle of Brooklyn. It was the bloodiest battle of the Revolution, and arguably one of the most critical — were it not for the Marylanders we could have lost the war before it had even begun. Chas M. Higgens, a member of the 1914 South Brooklyn Board of Trade, delivered an impassioned speech in defense of the Gowanus Canal, hailing it as the true birthplace of America. “When you passed [the Statue of Liberty] to-day you could have noticed that the face of the Goddess was not turned towards Manhattan or Jersey, but towards the shores of Old Gowanus.”

That’s not actually true — she’s supposed to be facing where the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge now stands, to welcome incoming ships, but it’s still an odd thing to think about in the bar. The Birthplace of America, where someone is wine-drunk and weeping. The Birthplace of America, where two patrons are arguing about who had the worse stroke. The Birthplace of America, where I am forcing everyone to watch The Bachelorette on my birthday. “Listen, I’m not a straight woman, but why in the hell would you wanna fuck a guy named Tanner?” was the Rawley Post’s hot take on the 2015 season of The Bachelorette.

Founded in 1919 to support soldiers returning home from the First World War, the American Legion is a non profit that remains the country’s largest federally chartered veterans’ organization. But as it approaches its centenary, membership is on the decline. Walk into the Rawley Post on any given weeknight and you’ll usually find a few guys drinking at the bar and a pile of uneaten McDonald’s cheeseburgers sitting on a table by the wall. John Lonergan, a long-time member and the current commander of the post, brings them by but he always seems to overestimate his crowd.

The post bought the building in 1962, which should have assured them a measure of financial security, even as Gowanus rents skyrocketed. Lonergan was elected mid-June and took over July 1st, 2016; immediately there were problems. A check for $600, written to a member who’d done carpentry work on the floor and the bathroom, bounced because of insufficient funds. “We thought there was $26,000 in the working account,” Lonergan said. Instead it was overdrawn by $2,000. According to Guidestar’s listing the post hadn’t paid taxes in over three years. None of its members had any idea.

To an outsider, the power structure within the American Legion can seem a little odd. Everyone is called ‘commander,’ the national commander, the state commanders, the district commanders, and the individual post commanders. Even the bar language is militarized. I reported to the lead bartender, whom they called the Bar Captain. As a veteran’s organization the language is justified, but it can seem kind of goofy — a bunch of old men hanging out in their treehouse, arguing over strange internal politics.

Not every Legion has a bar, and the ones that do typically don’t make a huge profit off beer and liquor. Not surprisingly, the members keep voting against raising the prices — at the Rawley Post a pint of Budweiser is still two dollars and an eight-ounce glass is seventy-five cents. Members pay dues every year, but most larger American Legions rent out their back rooms for weddings, graduations, and other parties to bring in money.

At the Rawley Post a pint of Budweiser is still two dollars and an eight-ounce glass is seventy-five cents

When Rawley’s previous commander took over, he brought in a non-member to do the bookkeeping. They quickly took over running the parties in the back room and doing all the ordering for the bar. The bookkeeper, the previous commander, and the former treasurer, all had access to the checking account; as of this writing the Brooklyn District Attorney Frauds Bureau is in the process of issuing subpoenas to them all. “This place has a history of uh…” Lonergan trailed of and shrugged. “People get in here and they have sticky fingers. It’s been looted for years.” Lonergan told me about another former commander — now deceased — who rented out the Rawley Post’s parking lot to a nearby bar and kept the money for himself. Yet another commander was supposedly in the habit of absconding with money from the bar cash register.

Petty theft is hard to prove because up until this point the Rawley Post has dealt primarily in cash, but while skimming money off the top may not be so unusual, large-scale embezzlement is unprecedented. They’ve lost their tax-exempt status, they owe over three years in back taxes, and they’re broke. Checks made out to the liquor and beer companies have bounced, which could get them blacklisted and reported to the State Liquor authority. They’ve got a $200,000 investment that they can’t find, according to Lonergan, who said many of the files are missing and the computer has been locked. When he took over, even the Joker Poker machines had been cleaned out.

They’ve lost their tax-exempt status, they owe over three years in back taxes, and they’re broke.

“There’s so much malfeasance,” said Lonergan, sounding tired. “We went to the D.A. and said we’re not accusing anybody, we don’t know who did it, but we’re broke and we don’t know anything. We wanna take over with clean hands.” The D.A. was not able to comment as to whether there was or was not an ongoing investigation.

Even when rampant theft isn’t an issue, American Legions aren’t doing well across the country. In just the last five years, national membership dropped twenty-three percent; twenty-seven percent in California, twenty-one percent in Illinois, and twenty-two percent in Pennsylvania. The 2016 American Legion convention, where both Clinton and Trump will be speaking, begins August 26th. Trump recently criticized a Gold Star family, so it’s likely that the convention will be somewhat tense, but last year’s wasn’t all smooth sailing either. In the transcript of the 2015 American Legion Convention, held in Baltimore August 28th to September 3rd, National Commander Dale Barnett chewed his subordinates out over membership:

We talked about a culture of growth, and they told me wonderful things. But the reports are not showing that we have a culture of growth. We only have six departments right now that, at this point in time, are ahead of where they were last year. That’s not the direction I want to go as your commander. That’s not the direction we need to go. I know it’s difficult. I know it’s hard. But I know that you want to be on a winning team, and we’ve got to turn it around.

Barnett is a Desert Storm vet who coached high school basketball, baseball, and cross country, and he sounds like it. But he’s right. In just the last five years, New York State membership has dropped twenty-six percent. “The biggest obstacle is really over-saturation of veterans’ organizations that are out there,” said Frank Peters, former New York State Commander. “Back in the sixties there were about four or five, now there are twenty-two just that I can think of offhand. I think we just need to do a better job of advertising, you know. We are the American Legion. We wrote the G.I. Bill.”

Tom Long, who’s been the commander of the Continental American Legion in Queens since 2010, sees the generation gap as the biggest problem. American Legions largely exist in a pre-internet state, so Long has been talking with a young man who was recently discharged from the Air Force about advertising to potential recruits through Facebook.

Chy Mitchell, a retired army nurse and the commander of the thriving American Legion Post 398 in Harlem, credits their success to staying proactive about engagement. She’s also focused on increasing membership amongst female veterans, who have long been sidelined. “If you don’t keep that connection going on it knocks down your membership,” Mitchell said. “Cause then you’re bored. You’re boring. It’s not just a stale thing, you know. You just pay your dues and come and sit and do what? Drink? You can go to any bar and drink.”

Historically, World War II veterans have been the the Legion’s most dedicated base, but that base is aging out. According to V.A. data collected by the World War II Museum about four hundred and thirty-one WWII veterans die every day, and by 2037 they should be gone entirely. The V.A. estimates that there are 22 million veterans alive today, as of 2014 four million of them were post-9/11 vets, but they’re just not joining. “I mean no, right now I’m not worried,” said Craig, a bartender and member at the Bay Ridge American Legion. “But in twenty years…yeah. Then we’ll be in trouble.”

Because American Legions tend to outlast most other businesses by decades, especially in gentrified or gentrifying neighborhoods, they become informal community centers and repositories for weird, outdated gossip. It’s reflected in the peculiar speech patterns of the patrons — tenses and timelines are muddled and unless you push for dates it’s hard to tell whether the events being described happened two years ago or twenty. “I go by — was it before or after I got hit by the car or was it before or after 9/11, those’re my two points of reference now,” Marty Boorman, a Vietnam veteran and retired electrician, said cheerfully.

Stories are told with the oblique, elliptical language of the folktale and repeated to whoever will listen until they become part of the bar’s unofficial canon. The dead never really get to die here because the living won’t stop bitching about them and death is a familiar, even friendly, subject — more because of the patrons average age than their combat experience. Marty tells me about about a cousin of his who got mixed up with the mob and ended up laid out on Ovington Avenue, shot five times.

“The sixth bullet, the guy put the gun next to his head and the gun wouldn’t fire. He was in the hospital fourteen months,” Marty says. “[His wife] had just had a baby. The kid, by the time he was able to get outta the hospital the kid could’ve walked down to church to get baptized. That was the highlight of the christening; the baby and the jacket he was wearing when he got shot. More people were interested in looking at the jacket than the baby.”

Mary Karr famously referred to her father’s American Legion as “the liar’s club,” because of the amount of bullshitting and grandstanding its members did amongst themselves, but she recognized its importance. “Something about the Legion clarified who I was,” she wrote. “Made me solid inside…That bar also delineated the realm of sweat and hourly wage, the working world that college was educating me to leave. Rewards in that realm were few. No one congratulated you for clocking out. Your salary was spare. The Legion served as recompense…You attended the place, by which I mean you not only went there but gave it attention your job didn’t deserve.”

Mary Karr famously referred to her father’s American Legion as “the liar’s club,” because of the amount of bullshitting and grandstanding its members did.

Today, the number of people who care enough to pay attention, much less pay dues, is dwindling rapidly. There’s a tradition at the Rawley Post called sign in. Members write their name on a slip of paper and push it towards the bartender with fifty cents. Every day the bartender pulls a number out of a plastic jar, which is cross referenced against a list of names. If the member signed in the day before, they win the money. If they didn’t, the money is added to the pool. The list isn’t updated very frequently though, so it can be kind of a grim task. Sometimes when the bartender pulls a name, the member has been dead for years.

The Rawley Post is closed Mondays and Tuesday now because of its financial issues — opening on those nights isn’t worth the price of air conditioning. A napkin holder advertising Pharrell’s Qream still sits in front of a Mass Card. Old photos and newspaper clippings cover a bulletin board on the door to the back room. “As Hippies Partied — Meanwhile in ‘Nam,” reads the headline of one article on the evils of hippies. Once you walk in you could be anywhere in the country, but in a building that old, with that many dead bodies around it’s hard not to get a little spooked when the lights flicker.

“Nah,” said Marty, when I asked if the post had any ghosts. He laughed. “Anybody who’s haunting the place is still alive.”

Rebecca McCarthy is an Awl intern and a bookseller.

How Can Detroit Improve Its Disastrous Public Transit System?

This November, constituents will vote on a proposal to fund a $4.6 billion overhaul

Detroit’s public transit is widely regarded as the worst in the United States. At the edge of downtown Detroit sits the Rosa Parks Transit Center, the raucous and at times chaotic central hub for the city’s bus system. Last week, hordes of passengers shuffled about the hub — a minimal facility with a small indoor waiting area and a roundabout for buses to dock.

“Zero-to-10, 10 is awful? I’d give it an eight,” said Roberto Rodriguez, a sixty-seven-year-old retired veteran who lives in the city’s Southwest neighborhood. Short and portly, wearing a Vietnam Veteran’s hat to mask a mat of gray hair, Rodriguez said he doesn’t use the Detroit system much anymore. About once a month, he takes a bus to the local Veteran Affairs hospital, near Midtown. “It’s just more convenient for me,” he said. In the city of 680,000, one-quarter of households don’t have access to a vehicle.

In the city of 680,000, one-quarter of households don’t have access to a vehicle.

“There’s not enough buses, there’s too long of delays, there’s not enough shelters, bus stop shelters for people in the rain,” he said. “And the thing that pisses me off the most about Southwest Detroit — besides not having enough buses — is that the signs, there used to be signs where the bus stops were.” He raised a finger to emphasize the next point: “There’s one sign between Livernois and Scotten,” he claimed, in reference to a mile-long stretch along the area’s main drag, Vernor. “One friggin’ sign.” (SuVon Treece, Marketing Manager for the city’s bus system, said that “could be accurate,” but it hasn’t received a complaint. The city has since launched a project to review individual routes and assess bus stop signs, and Treece said: “When we receive complaints, then we make sure to get the signs out.”)

Rodriguez mused about a common sight in his neighborhood. “So I see these mamacitas and abuelas with bags, and they’re walking around, and they’re saying: Señor, señor, where’s the bus? And they’re walking down with a bag or two, or pushing a cart load — and the fucking bus goes right by them, because they were not standing where they need to stand. There was no sign. It’s outrageous. I see it every week.”

For decades, officials have sought to establish some semblance of a functional, connected public transit system across Metro Detroit. Decades ago, the region infamously squandered a pledge of hundreds of millions of dollars for public transit from President Gerald Ford’s administration after local government couldn’t agree on how to organize a central authority, largely due to intense political rifts between the suburbs and the city. But in 2012, after two dozen failed attempts to create an agency to oversee public transit, state lawmakers formed the Regional Transit Authority of Southeast Michigan (RTA).

From the outset the agency has hobbled along, with little funding to get on its feet. And, last month, it nearly fell apart when representatives from Oakland and Macomb counties dredged up old sentiments: The board members felt they were getting a raw deal on the RTA’s Master Transit Plan. Oakland County executive L. Brooks Patterson said, “I cannot in good conscience support the current plan, which spends over $1.3 billion of Oakland County taxpayers’ dollars over 20 years, but only gives our businesses, workforce, and residents a fraction of that back in transit services.”

Why, he argued, should Oakland County tax dollars support, say, a streetcar system that only runs in Detroit? (A New Yorker feature on Patterson from January 2014 was titled, “Drop Dead, Detroit!”) In recent years it felt as though change were afloat: counties surrounding Detroit supported regional taxes for the Detroit Zoo, Detroit Institute of Arts, and a new regional authority to oversee the Detroit water system. But Patterson’s RTA representatives said the proposal could be a “detriment” to the current suburban bus system and its riders. The officials said, “the plan fails to demonstrate with specificity just how the financial resources to do so will be guaranteed to each agency to allow that goal to be achieved.”

Still, if the RTA’s estimations are on target, the suburbs could stand to gain significant access to more of the region: The agency said 92% of jobs within southeast Michigan aren’t accessible by a sixty-minute trip on public transit. The region also only spends $69 per capita on public transit operations, compared to $119 for Atlanta, or $471 for Seattle.

92% of jobs within southeast Michigan aren’t accessible by a sixty-minute trip on public transit.

The $4.6 billion master plan envisions a massive overhaul of public transportation across the region, including rail service between heavily populated cities like Ann Arbor and Detroit; new bus rapid transit lines along busy corridors and to the Detroit airport; and coordinated service among the suburban and city bus systems, with new express routes aimed at reducing long waits. Eventually, the RTA says it’ll assume oversight of a 3.3-mile streetcar line on Woodward Avenue in downtown Detroit.

Eric Green, a fifty-seven-year-old native Detroiter who has been taking buses for over three decades has seen improvements in the city’s bus system since Detroit’s new mayor, Mike Duggan, took office. Of the new buses, he said, “it seems like they don’t break down as much as they used to.” On any given day, he’ll wait upward of forty-five minutes to an hour for a bus to cart him across the city from the west side where he lives to his job at a car wash, just outside downtown. The ride, including at least one transfer, lasts about an hour. Green seems resigned to the typical waits for a bus to arrive, but he said the city’s system still has its problems.

“You wish there were more buses out, especially in the winter time,” he said. “That’s when it’s really bad.” Like many riders scattered about the transit center, he hadn’t yet heard of the RTA’s expansive new plan. But the streetcar on Woodward, known as the QLine and under construction since 2014, doesn’t interest him. “I’m not into that,” he said, turning on a common refrain shared about the streetcar: “I mean, it’d be cool if it was going further, to [the city of] Pontiac or something like that. They should stretch it.” He went on, “My job is right downtown, but people have jobs way out where they need the transportation. It’d be cool if it was further.”

Otilia Jones, an auto worker in her fifties, echoed Green’s comments on long wait times. “In the winter time, sometimes you wait maybe two hours for a bus,” she said. “That’s uncalled for.” Her colleague, Londell Coles, said that two weeks ago, his morning bus to commute for work never showed up. In a city where the unemployment remains in the double-digits, the repercussions of a no-show ride are vast.

“In the winter time, sometimes you wait maybe two hours for a bus”

“I have to wake somebody else up in the morning to have them come pick me up, and drive me all the way down here, then go all the way home,” he said. “I can’t afford to be late for work.” Coles said he once waited two hours for a bus to arrive; Jones, who said she has used the city’s bus system “all my life,” bested him by an hour.

Whether the plan has potential to become reality is left to the ballot box this November: the RTA board earlier this month approved a ballot proposal that asks voters to green-light a property tax increase to fund the agency for 20 years, a roughly $8 per month increase for a home assessed at $78,856, the average value for a household in the region.

Patterson and Macomb County executive Mark Hackel, the hesitant county execs eventually came around and supported the plan, saying that, with adjustments, they believe it incorporates the entire region. (Hackel, seen as a likely Michigan gubernatorial candidate in 2018, was reportedly bothered by criticism that race and objection to the city played a part in his initial objections; he countered it was aimed solely to ensure his constituents receive decent service and sound governance of the RTA, “nothing more, nothing less.”)

Officials backing the plan still potentially face an up-hill battle: Voters have recently signalled support for public transit, approving a small tax increase for the suburban bus system, which operates some routes into Detroit. Perhaps a 15-year project to rebuild a busy highway in Oakland County will convince more motorists to lend additional support to transit instead.

It remains to be seen whether the RTA proposal will garner a similar level of support as the regional zoo and art museum taxes. Whatever it takes though, public transit has to improve. “The system has to get better,” Jones lamented. “Who’s got $25 to get a cab every day to come downtown?” she said. “That’s money you lose.”

Ryan Felton is a journalist who lives in Detroit.

Youandewan, "Ciel"

What would you do in space?

Do you ever wish you were in space? I do. I do quite frequently. In space, they say, no one can hear you scream, and the only thing that is keeping me from screaming here on Earth is the fear that someone might hear me, because both the volume and duration of the scream that I would emit were I ever able to do so without worrying about anyone around me would be so unprecedented and terrifying that it might cause a cascading crescendo of howling so severe among others that the human race would howl itself into extinction. If I were in space I would scream the scream that I have been keeping myself from screaming to save the rest of you. If I were in space I might never stop screaming. And that is why I wish I were in space.

Anyway, here is a track from “Berlin-based Yorkshireman @Youandewan,” who “brings sweeping sci-fi pads, lightly de-tuned keys and arpeggios that plonk you straight into the driving seat of your own galactic cruiser.” It’s like you’re piloting a scream machine of your very own. Enjoy.

New York City, August 16, 2016

★★★ It was hard to tell whether any of the stone fruit, fresh from the refrigerator truck, had ruptured in transit, or whether the bag was just dripping with condensation. The air was still heavy, though cooler for a moment, till the sun reached a thinner part of the clouds. More clouds came, fending off the worst of the heat again. Heavy gray arrived right overhead, and then, in the time it took to get the swimming things, the outdoors changed over to full sunshine and a downpour. For a moment it was hard to separate the bright splashing in the forecourt into its components. Presumably somebody somewhere got a rainbow out of it. Within an hour, any remaining clouds were gone and so were the sheets of water, save a few puddles that could have been there all along. More clouds rode in on the evening, though, and with them strong lightning, loud thunder, and eventual unspectacular rain.

Wheel of Fortune

Will a change in the way America names its cheeses hurt sales?

If you were to ask a random American what he or she thinks about the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), it’s safe to bet they wouldn’t have much to say. The European Union-United States trade deal, first floated in 2013, makes the news on a near-daily basis across the pond. However, whether because the US has been so opaque on the details of ongoing negotiations, or because many of the issues involved feel abstract from daily life, many Americans don’t even know what the TTIP is.

And yet, deep within the bowels of the treaty, there’s one clause that could have a profound effect on everyday American life — by making it illegal for US cheese makers to use common names rooted in regional European culinary traditions like feta, muenster, or parmesan. EU negotiators are serious enough about this that it’s had the US dairy world in a tizzy for two years, underscoring how attached our cheese culture is, both emotionally and financially, to its (often only name-deep) European heritage.

One clause [could make] it illegal for US cheese makers to use common names rooted in regional European culinary traditions like feta, muenster, or parmesan.

This provision is just the latest in a long crusade by traditional European cheese makers against the willy-nilly usage of their region’s dairy terms by foreigners. In the early 20th century, some European states blocked the importation of foreign products using their names, hoping to protect the integrity of their culinary heritage. Predictably, France was among the first to implement a cohesive system of cultural protections for their cheeses, limiting the use of the name Roquefort in 1925. But other nations like Greece, historically less litigiously finicky about their food, jumped on the boat as well. Starting in the 1930s, you couldn’t sell brined goat or sheep’s cheese under the name “feta” in Greece unless it was verifiably made in specific regions of that nation using exact ratios of sheep’s milk to goat’s milk.

In 1992, the EU picked up these precedents and codified a “Protected Designation of Origin” system to judge which names, tied to traditional regions and modes of production, ought to be protected throughout the Union. It was a move geared towards protecting the flavor integrity and economic viability of traditional products. To wit, after the EU embraced Greece’s claim that feta was a distinct regional product in 2005, other European feta makers weren’t just barred from selling their products in Greece. They also could no longer call their cheeses feta in total — to the chagrin of British, Danish, and German producers who’d long dominated the EU market with cow’s milk feta and to the benefit of poor cheese makers in the rural Greek mountains.

Since then, the EU has slapped these protections onto about 180 cheeses, including Asiagos, Bries, Camemberts, Gorgonzolas, Goudas, Gruyeres, Manchegos, and Provolones. EU officials have been so pleased with the benefits of these cultural protections, building the exclusivity and thus brand strength and profitability of cheeses on the continent, that they’ve sought to extend them across the world via trade treaties, including one finalized between the EU and Canada in the summer of 2014, which is currently just awaiting implementation.

In early 2014, American cheese makers realized Europe’s push to extend the frontiers of their cultural protection regime included the TTIP and freaked out. According to Massimo Vittori, managing director of the Geneva-based pro-cultural protection group oriGIn, at least 70 cheese names that most Americans consider generic conflict with European restrictions. American cheese makers, from industry powerhouses like Kraft-Heinz to Midwestern craft producers, say they’ve spent decades and gobs of cash developing brands built on these generic names — just think about every tube of grated white stuff in the refrigerated aisle of your grocery store you associate with parmesan or every deli slice you associate with muenster.

At least 70 cheese names that most Americans consider generic conflict with European restrictions.

Some claim American producers and marketers actually built the international reputation of and demand for European-heritage cheeses that EU producers now want to leverage through cultural protections. They fear that, if they’re forced to start calling their products brined cow’s milk cheese instead of feta or parmesan-style hard cheese instead of parmesan, they’ll lose global market recognition—they’ll seem cut-rate. No one I spoke to in the US cheese industry could put a figure on it, but they all suspect this would take a fair chunk out of the multi-billion dollar industry, jeopardizing the well-being of many dairy farmers and manufacturers at home for the benefit of small pockets of farmers and producers abroad.

Naturally, a bipartisan group of 55 senators attempted to protest the provision — because cheese is perhaps the one thing that can unite this nation, even today. And the US has officially pushed back, arguing that EU producers can just file trademark applications for protection in the US. Just like under the EU’s system, this would prevent people other than the trademark holders or licensed users from labeling their cheese with specific names in America. However we don’t issue trademarks for names we consider too generic, like parmesan, which Americans have long used as a general term for a hard white cheese.

Shawna Morris, who handles trade policy for the National Milk Producers Federation and US Dairy Export Council, points out that a number of European cheeses included on the list for protection, like Roquefort or Parmigiano-Reggiano already have trademarks. But for Europeans that’s not enough; the trademark for Parmigiano-Reggiano doesn’t extend to parmesan, which to them is a synonym, not a generic genus term.

“If the [European negotiators] spent as much time and effort helping [producers] simply register their names through the existing system as they have in trying to impose new restrictions in the US market,” Morris said, “their goal of greater protection for EU terms would have already been achieved. It’s a shame, really, because [they] continue to adamantly refuse to acknowledge that it is actually US producers who face genuine trade barriers in this context. It’s US companies that cannot sell asiago or feta to the EU and increasingly to a number of other global markets, directly as a result of inappropriately broad EU… policies.”

Despite staunch pushback and accusations that the EU’s bid goes beyond protecting its farmers and moves into an overreaching protectionist assault on American dairy, the EU has stood strong; 201 of Europe’s over 1,300 cultural food protections show up in papers from TTIP negotiations this spring, 78 of which are cheeses. Just last month, an event hosted by the EU included a session on the importance of global recognition of these protections for the security of regional agriculture within the bloc, which used cheese as a key example.

It’s a stubborn position born of a firm conviction that generic American cheeses, no matter how long they’ve used the terms or how many dollars they’ve sunk into branding, are clearly just piggybacking on the haute reputation of their classier European kin. That’s not always the case — as Morris points out, some American cheeses have won international awards going head to head with EU-made counterparts — like BelGioioso Parmesan, which took first in class in global competitions in 1986, 2010, and 2012. But Europeans do have a point that many American parmesans taste nothing like their continental equivalents, because they use ingredients Italians would consider unholy—like cellulose powder and potassium sorbate—and then market themselves using Italian imagery or oblique references to the quality and story of Parmigiano-Reggiano.

The same could be said of American fetas, which may be part of our heritage through southern European immigration, but which cannot truly mimic traditional tastes due to federal regulations on US cheese production and the usage of non-traditional materials like cow’s milk instead of sheep’s and goat’s milk in many offerings. Even if we popularized the terms and sometimes do credit to their heritage, that doesn’t mean we don’t also often irresponsibly capitalize on and detrimentally bastardize that heritage.

Many on the European side have tried to convince the US industry that the TTIP is an opportunity to build strong local brands, which could be more profitable in the end. OriGIn’s Vittori points out that a similar deal in Australia killed its dependence on “generic” wine names rooted in European heritage, like Chablis or Champagne, which folks in the know realize are tied to specific regions in France, but which many firms in Australia at the time (and in America now) used to up their class factor and sales. In the aftermath, Australian vintners created wildly successful narratives of local wine region-brands like Barossa Valley or Margaret River. Vittori thinks there are at least 500 products that the US could create culturally distinct and protected titles for, including many cheeses, giving a massive boost to local producers offsetting any damage the recognition of European protections might do.

“From the marketing perspective,” he told me, “more and more consumers are looking for authenticity…leveraging specific characteristics of place.” Already, producers of US cheeses like Grayson, Hooligan, and Humboldt Fog have drawn on their location or unique processes and ingredients to establish popular and profitable American brands.

Vittori hasn’t, he admitted, found much traction with this narrative. “We have a good dialogue,” he said, “but as far as I understand, the [US] position remains quite skeptical.” That’s mainly because local cheese makers can easily point to the pain their European counterparts say forced name changes caused them, or the trouble Kraft-Heinz faced when, in 2008, it was finally forced to rename its parmesan “pamesello” in the EU, as proof that these restrictions are just painful trade barriers designed as political tools to hurt viable and large-scale American producers.

“local cheese makers can easily point to the pain their European counterparts say forced name changes caused them”

US producers seem to be so convinced that this potential forced name change is a fundamental injustice, violating the values of free trade and fair usage, that no one I talked to was aware of any efforts to come up with contingency plans for rebranding or repositioning. Instead, explained Doug DiMento of the Northeast’s Cabot Creamery Cooperative, “we’re simply trying to fight.” The industry has formed an entire lobbying group, the Consortium for Common Food Names (whose media outreach Morris runs), to push back on European cultural protections in the TTIP.

Chances are the entire TTIP deal is not going to freeze over a debate on the rightful usage of the term parmesan. So, given how entrenched the US position is, it’s likely we’ll see some kind of compromise. Vittori has floated the idea of allowing the US to use names we consider generic under certain conditions, such as not associating our parmesan with Italian cultural symbols; maybe we could make hyphenated American-X cheeses, making it clear there are differences between traditional European cheeses and their fine American cousins. The details of those compromises would have to be hashed out by producers on both sides of the Atlantic, though.

In truth, it’d probably be good for US producers to move away from explicit callbacks to our European heritage, as a matter of pride in our local products, a move in the direction of US food trends that privilege a clear and local provenance, and a means of allowing consumers to better understand what they’re buying — something the US historically sucks at.

It’d probably be good for US producers to move away from explicit callbacks to our European heritage.

Renaming our cheeses, say, Oregon cow feta or something totally novel doesn’t seem so bad. But the fact that a multinational trade conflict has spun out of cheese name usage rights says something about the perceived value of an established brand — and the abject fear the prospect of a forced change can inspire. This obscure trade deal about which so few of us give a shit has the potential to make us more food-conscious consumers and benefit local brands and producers. It also has the potential to put a dent in the US dairy industry. Either way, it’s a conversation we’re going to have.

Not The Safe Space You Were Thinking Of

Is a high-end coffee shop in a gentrifying neighborhood just a refuge for wealthy whites?

The initial six-stop stretch of the L line in Brooklyn, between Bedford and Morgan avenues, is an expanding block of homogeneity. After rezoning allowed for new developments along the route in 2005, those with access to reasonable amounts of capital descended upon the region, alongside graduates of a particular set of universities with a singular vision of rustic creativity that still defines “Brooklyn” to this day. Even though the slow migration of this demographic to the the area dates as far back as the ’80s, the past decade — perhaps crowned with the addition of a Whole Foods and an Apple Store last month — has seen Williamsburg and Bushwick fully transformed in the image of the types of inhabitants early developers hoped to attract. The region now functions as a “safe space” for a type of person who pursues a lifestyle associated with white, educated, and upwardly mobile young people.

The idea of safe spaces, often maligned by conservatives as politically correct nonsense, predate collegiate controversies and speeches from billionaires who like to hold grudges. The concept has origins in the early women’s movement as gathering places for women to generate strategies for resistance — as well as simply to not be surrounded by men, for once. The idea extends to any group of people looking to commune, or hang out, or scheme, in peace. At its core, demanding safe space is demanding dignity.

That the resources to make safe spaces out of your physical surroundings are consolidated among white people in the form of generational wealth—which allows white millennials to reach financial milestones like home-ownership at higher rates than minority millennials—makes homogenous development a constant. When upwardly mobile whites flock to urban centers and bring with them the trappings of a particular lifestyle, they effectively create a safe space out of another community’s tepidly existent one.

At its core, demanding safe space is demanding dignity.

The contagion-like spread of well-off whites in Brooklyn, often with the help of government, is a tactile representation of the types of privilege built in to how society functions. Possibly as a result of Bill De Blasio’s Affordable Housing Plan, which incentivizes new development in East New York, there is currently a great deal of interest as far along the L line as Wilson Avenue, where Routine, a new cafe opened by Corcoran realtor David Taylor, opened earlier this year. An art school graduate from Michigan, Taylor lives in the same Bushwick neighborhood where his shop — a cozy freelancer’s paradise with ample outlets, Toby’s Estate coffee and delicacies like avocado toast — is seen by some as the beginning of a forceful claim of space over the community.

Taylor told Bushwick Daily, “I started to notice the push to buy in this area of Bushwick. Then quickly noticed how under served the area is for good food and coffee and decided to fix it.” Taylor, a realtor whose email signature includes the words “Multi Million Dollar Club,” told me in an email he thought the claim that coffee shops like his created safe spaces for white people at the expense of minorities was offensive.

“Minorities are not being pushed out by Routine. Is the idea that nice places can’t exist in areas that have a primarily minority population? It’s absurd. The premise is, in itself, racist and I resent it.” He said, before adding, “it should not matter, but would it change your story to know that my [business] partner is black and he’s owned the building for 20 years? We have a black-owned business, opened and thriving in his own community. Why wouldn’t we want to open something to make our neighborhood nicer?”

Taylor’s point is a familiar one. As Sarah Schulman wrote in The Gentrification of the Mind, “gentrification is a process that hides the apparatus of domination from the dominant themselves.” The tax breaks that allow the developments listed in the area by Corcoran, for example, are what would naturally drive up demand for high-end coffee that far into Bushwick. Taylor, who has opened a number of restaurants in the city, isn’t on the hook for why or how neighborhoods like Bushwick morph in the image of people who look like him; he merely profits from it.

When I asked whether or not he thought the shop was explicitly making this community more comfortable for white tenants he responded, “You’re implying that minority tenants of the neighborhood aren’t also more comfortable in their neighborhood having a nice place to get quality food and coffee. Yes.. it makes certain types of tenants more comfortable; as well as everyone else.”

The tax breaks that allow [development] are what would naturally drive up demand for high-end coffee that far into Bushwick.

It is true that such changes have generally positive effects on neighborhoods. A group of Yale researchers found that in Chicago, a higher concentration of coffee shops in a neighborhood was associated with a decline in reported shootings. It is a familiar refrain in Williamsburg, too, where most would agree that the current hyper-developed version of the neighborhood is preferable to the neglected industrial zone it once was.

The nature of these “improvements,” however, is chilling. Sociologists Jackelyn Hwang and Robert J. Sampson published a survey of gentrification in Chicago neighborhoods and found that rather than move into predominantly black neighborhoods, white gentrifiers tend to move to more ethnically mixed neighborhoods, driving down diversity until the neighborhood is homogenous. Neighborhood revitalization tends to exist in extremes that assume equitable growth for minority and white residents isn’t possible, and that, ultimately, nothing can stop wealthy whites.

Earlier this Summer, The New York Times reported on an increasingly volatile situation at Brooklyn Bridge Park, specifically on the 85-acre park’s basketball courts. In recent months, a number of fights have broken out on the courts, which spill out into nearby Joralemon Street, and have residents of the affluent neighborhood on edge. Gothamist reported that some residents feared for the “character” of their neighborhood and others called for the removal of the courts all together. The proposed replacement? Tennis courts. The violence at the park, which on at least one occasion involved a gun, is certainly a cause for concern, but something about replacing storied Brooklyn basketball courts with tennis courts seems particularly aggressive.

In the Times story, 17-year-old Aaliyah Johnson, who is black, said, “Sometimes I try and avoid going on Joralemon, it’s like they look at you, move their kids over like you’re going to do something, and clutch on to their purse. You’re doing that — it just makes us not feel welcome. We just came here to play basketball.” While the proposed removal of the courts was eventually shot down, it isn’t hard to imagine stories like this taking place around the country, as the safe space of wealthy whites expands like Manifest Destiny.

“Sometimes I try and avoid going on Joralemon, it’s like they look at you, move their kids over like you’re going to do something, and clutch on to their purse.”

Efforts to truly revitalize “forgotten” communities should address the reasons they were forgotten in the first place. The pattern that has emerged, driven by an assumed blindness to race, allows white privilege to consume itself, expanding in search of diversity only to push diverse populations out again and again. A report released this week by the Institute for Policy Studies suggests that if current public policies stay the same, it will take over two centuries for Black families to attain the amount of wealth that white families have today. For Latino families, it’ll take eighty-four years.

Safe spaces represent a social reality. People want to be empowered to make the area around them nicer, to exist freely in their community and feel a sense of equity to their homes. The seemingly endless conversation around gentrification should consider this more evenly. Nice amenities like coffee shops often appear first in a neighborhood before bodegas and corner stores start taking on a different character and, seemingly overnight, the number of brown and black faces in a neighborhood drops and sameness settles in. The expanding block of sameness present in Williamsburg and similar neighborhoods around the country will surely keep growing as long as some “safe spaces” remain valued above others.

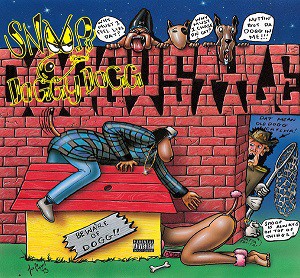

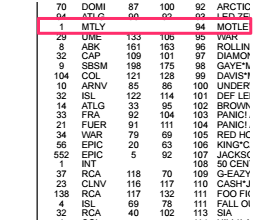

Soundscan Surprises, Week Ending 8/11

Back-catalog sales numbers of note from Nielsen SoundScan.

The definition of “back catalog” is: “at least 18 months old, have fallen below No. 100 on the Billboard 200 and do not have an active single on our radio.”

You don’t usually see that many surprises in the top ten to fifteen of this list, which are all selling three to six thousand records per week (Twenty One Pilots’ Vessel continues its streak at #1, I don’t know for how many weeks because I mostly just ignore them, sorry). Hence, Amy Winehouse and N.W.A. REMEMBER DOGGYSTYLE? I did not remember that it was one word. So, idiot that I am, I Googled “Doggystyle” to find an image of the album’s cover art, and let me tell you: don’t do that.

Frank Ocean’s Channel Orange got a nice little boost from his fakeout last week, and did you know who Elle King was? Me neither. She’s a singer-songwriter of some kind and also Rob Schneider’s daughter!! (Cc: Who Weekly.) A fun thing about the charts is that among all the other data they include (how many weeks the album’s been on the back catalog, number of copies sold, lifetime sales, etc.), they also include the label. Did you know Mötley Crüe had its own label, Mötley, whose abbreviation is MTLY?

Other new artists I learned about this week: Lecrae, a Christian hip-hop artist, and Sunny Day Real Estate, an emo ’90s alt-rock band from Seattle (obviously), third album’s title I find frankly confusing: How It Feels To Be Something On. Something on what, guys??? Finally, Keith Sweat’s Harlem Romance: The Love Collection sold exactly two more copies than Nas’s Illmatic. Surprise!! 😳 (I just learned how to type emojis on a keyboard.)

9. WINEHOUSE*AMY BACK TO BLACK 3,120 copies

11. N.W.A. STRAIGHT OUTTA COMPTON 3,028 copies

44. SNOOP DOGGY DOGG DOGGYSTYLE 1,862 copies

58. OCEAN*FRANK CHANNEL ORANGE 1,653 copies

60. KING*ELLE LOVE STUFF 1,630 copies

94. MOTLEY CRUE GREATEST HITS 1,379 copies

114. HILL*LAURYN MISEDUCATION OF LAURYN HILL 1,275 copies

139. LECRAE ANOMALY 1,183 copies

181. SUNNY DAY REAL ESTATE HOW IT FEELS TO BE SOMETHING ON 1,040 copies

198. SWEAT*KEITH HARLEM ROMANCE: THE LOVE COLLECTION 981 copies

199. NAS ILLMATIC 979 copies

(Previously.)

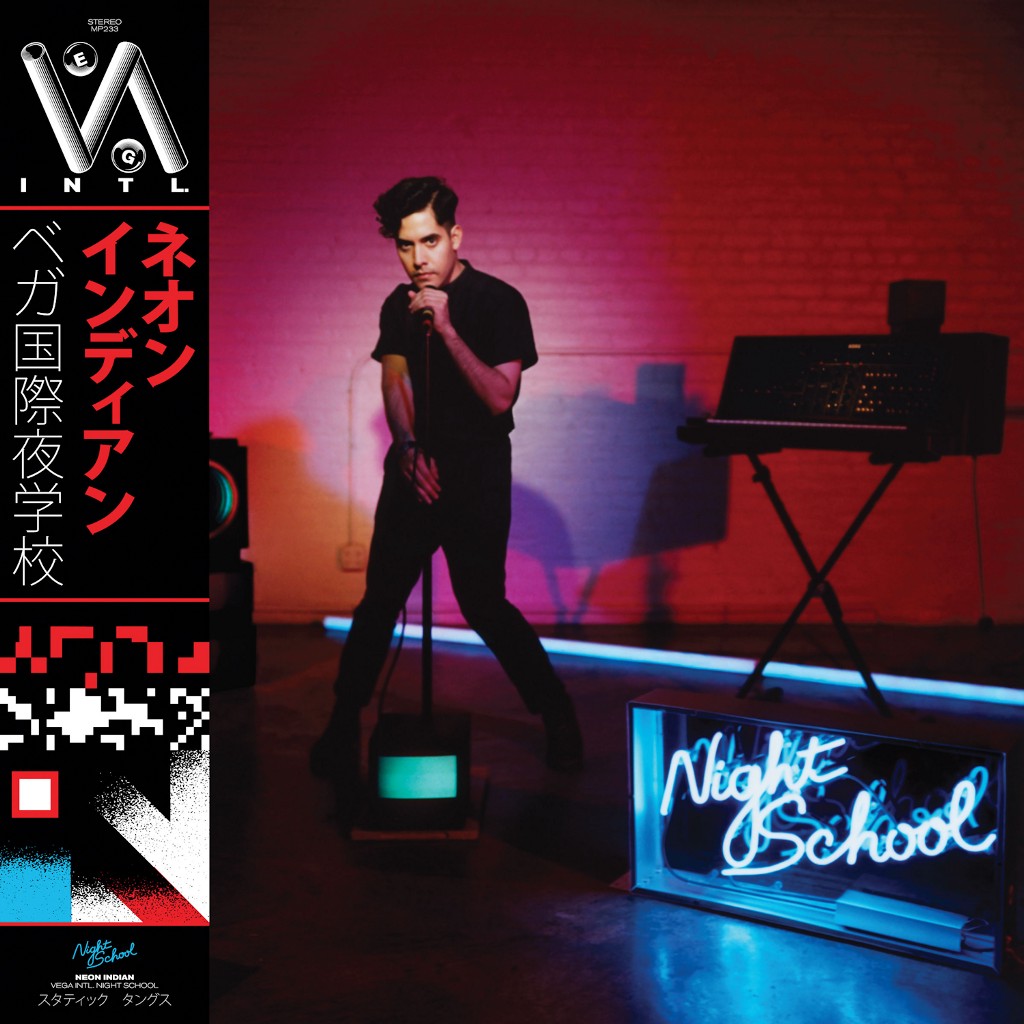

Neon Indian, "Annie"

Nothing retro was anywhere near as cool the first time around.

There will come a day for you too, young person, when all the referents that define “retro” are references for which you were there the first time around, and it will make you feel very old, very sad and very past your prime. Hopefully they will accompany something as delightful as this Neon Indian video. Enjoy.