Alcohol Makes You More Attractive To Dummy Chasers

Bite me, Science! “[A]ccording to a working paper from the University of Michigan’s Scott Rick and the University of Pennsylvania’s Maurice Schweitzer, just holding a glass of alcohol makes you look stupid. It does not matter if you’re male or female, or whether you drink beer or wine — if people see you drinking, they think you’re dumber than you’d otherwise appear.” Incidentally, it is 4:50. In about ten minutes I am going to look like a frigging imbecile.

What I Saw At The Toronto International Film Festival

by Michelle Dean

1. At the Toronto International Film Festival the other night, the woman directly in front of me in the rush line said she was an aspiring filmmaker. She was wearing a striped button up shirt, pleated khakis, and a blue nylon shell. She carried a thermos. If I had to guess her age, I would probably end up somewhere around 65. She wanted a free ticket, she told the volunteer wrangler. To anything. The wrangler, who was at the lower end of middle-age and clearly relished the authority she’d been temporarily granted, fiddled constantly with her headset to signal her importance as she listened to this.

“You have to pay for rush tickets,” she said, all business. “They aren’t free.”

“I know,” said the aspiring filmmaker. “But people come to the rush line to sell their tickets, sometimes, don’t they?”

“Yes,” replied the wrangler. “But ma’am, people generally want money for them. Usually they don’t give them away.”

“Still,” said the aspiring filmmaker, adopting a tone I can only describe as aunt-like, “Sometimes they do! I’ve gotten one before this way. Please let me wait.”

When the wrangler still looked dubious, the filmmaker added, “Please. I need to see some movies. I want to make them, but I can’t afford to see them. I haven’t even money enough for a camera.”

About a half hour later someone came by with tickets to a movie called Precious Life. No one was waiting for that movie, and so the aspiring filmmaker got her free ticket, and off she went.

I’ve been wondering ever since what kind of movies she wants to make.

2. It’s a strange thing how habits get started. I’ve only been going to film festivals of any kind since 2005. My first screening was at Lincoln Center, and it was of a little film called Goodnight and Good Luck, directed by a guy named George Clooney. It goes to show you just what kind of innocent I was that I showed up in what a friend calls my summer “uniform”: jean skirt, black t-shirt, black flip-flops, a canvas black messenger bag. On emerging from the subway, I discovered to my horror that you had to walk the red carpet to get in. And I did it-the photographers ignored me and the few other peons who also couldn’t find the alternate entrance-and took my seat three rows in front of Donna Karan and about twelve in front of Teri Hatcher (then at the height of her “Desperate Housewives”-related fame, so forgive me for recognizing her) and thought: “Oh God, I am never doing this again.” But then Clooney himself came out, dripping charm in a way I’d never seen anyone do before or since.

Since then I’d estimate I’ve gone to about fifty screenings at various festivals. Since Monday, I’ve been to four at this year’s iteration of the Toronto festival: Danny Boyle’s 127 Hours, Errol Morris’ Tabloid, John Cameron Mitchell’s Rabbit Hole and Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams. That list, although it mostly describes those movies I was able to get tickets to as opposed to all the ones I’d have liked to see-suggests that my film-nerd street cred is very questionable. I tend to like mid-list, largely American, or American-directed, work. My aesthetic, I suppose someone might say, isn’t overly sophisticated, more directed at heart than head.

3. I am not a squeamish person, but for the last thirty minutes of 127 Hours I kept having to close my eyes because a dull knife sawing through flesh apparently tests my limits. The performance anchoring the film is surprisingly good, largely because the script gives James Franco so many things to do physically that he has little time to get fidgety. The rest I am not crazy about, pretty though it is, mostly because Boyle’s aesthetic occasionally errs on the side of MTV literalness, which is basically what happens throughout 127 Hours. Shots of girls turning their heads, flashing white teeth shiny hair, and wide-open eyes, mascara running down their faces: these are Boyle’s shorthands for deep love.

During the Q&A;, Boyle was asked about the editing of the film, which is indeed stunning work, as the movie probably the most masterfully put together of any I saw this week. “I like to say I am very Tigger-like,” he answers. “And editors, they’re more… Eeyore-like.” I laughed like someone who knew what he meant. Maybe editors are all the same, no matter the medium.

4. At the Rabbit Hole screening I got my only real celebrity sighting. (Unless you count a brief glimpse of Don McKellar, which most non-Canadians wouldn’t.) Nicole Kidman and Aaron Eckhart showed up for the Q&A.; The murmurs in the press suggest Kidman will be up for an Oscar for her performance in this film. I think this prediction is probably apt; Rabbit Hole is the kind of movie the Academy loves, an elegy for a marriage in trouble after the death of the couple’s four-year-old. It’s adapted from the stage play by the playwright David Lindsay-Abaire. It’s a deeply felt movie, which should surprise no one who, like me, loves Mitchell’s other work (Hedwig and the Angry Inch, Shortbus). It’s also missing a little something I can’t quite describe, and has a clinical safeness that is also reflected in Kidman’s own performance. I have theories but few facts about the reason for that, so I’ll be delicate: let’s just say she just doesn’t get around to using the full range of expression she could have.

Someone in the audience does that thing I hate that people do at Q&As;, uses the question as an opportunity to talk to the question rather than ask a damn question. “I think this is THE MOVIE,” says the questioner, an elderly man I can’t actually locate in the crowd. “I think it will win the Oscar.”

Lindsay-Abaire grabs the microphone. “Thanks, Dad.” The crowd laughs uproariously.

Mitchell took back the floor. “Please don’t jinx us… Dad.” The crowd laughs again, right on cue.

5. Herzog had already left the festival for home by the time I saw Cave of Forgotten Dreams. It was probably for the best.

“This movie is not just a movie,” said the programmer, introducing it, “it is an art event.” Too right, I think, in the end. Though I suppose mine won’t be the dominant opinion, I think the film is too spare, relies too much on pretty photography of the ancient but only recently discovered Chauvet cave paintings in France. I am ashamed to confess that staring at these paintings for two hours does not, without more, do much for me.

There is some narration, but it is broad and bland, asking big questions like, “What is the human soul?” without the faintest interest in venturing answers. And it only offers only a few of the kind of details that end up following you all the way home. My favorite of these: they found, in the cave, an ancient footprint left there by an eight-year-old boy, and right next to it, the companionable tracks of a wolf. No one, apparently, has been able to figure out if they were left there at the same time.

6. At the end of Tabloid, Errol Morris comes up front for a Q&A.; The documentary itself is wonderful, a crowd-pleaser about a woman named Joyce McKinney. McKinney once made a name for herself in the tabloids by allegedly kidnapping her Mormon ex-boyfriend while he was traveling in the UK and chaining him to a bed, as the tabloids delightfully described, “spread-eagled.” This was all, in her view, a well-intentioned effort to rescue him from the church. The movie allows her to describe this for herself, and she does a bang-up job, I have to say. (There’s also a twist at the end I’ll resist spoiling.)

“This movie,” Morris says in his prefatory remarks, “has probably convinced me, once and for all, that love only requires the participation of one person.”

7. Potentially related: I generally go to film festivals alone. While I’m always happy to take people with me, I don’t condition my attendance on theirs. It often surprises others when I tell them that. I guess I’d rather see the movie alone than not see it at all. A lot of people see these things as social time, I guess, but I don’t get it. I’m there to watch a movie, I don’t need to chat. And as for people pitying me for being there alone, well, I long ago abandoned the idea that I would always be able to maintain my dignity in the face of my obsessions.

This also seems true of my fellow filmgoers at these screenings, few of whom are film students, as far as I can tell. Most are middle-aged yuppies. It takes money to have a hobby like this. The air, though, is not as self-congratulatory as you’d that might imply. I try not to over-rationalize to myself, but I often wonder if the enjoyment I derive from attending film festivals isn’t a kind of contact high from feeling, however briefly and peripherally, like I’ve become part of the production process by seeing it before other people.

I suspect this is not a healthy feeling. But I’m almost certainly going back next year.

Michelle Dean has written for Bitch and The American Prospect. She blogs at The Pursuit of Harpyness.

Photo by Josh Jensen, from Flickr.

NFL Gives Viewers Good Reason For Super Bowl Halftime Bathroom Break

Good news: The NFL has reportedly decided to book a relatively current musical act for its halftime show for the first time since the Super Bowl XXXVIII Nipple Flash! Bad news: That act is apparently the exactingly safe hip-pop collective the Black Eyed Peas. Mitigating factor: Maybe this means we won’t see will.i.am during every other commercial break? [Via]

PJ Harvey, "The Last Living Rose"

PJ Harvey, “The Last Living Rose”

Nestled in the extremely heartening announcement that Polly Jean Harvey could be releasing a follow-up to 2007’s White Chalk early next year was a clip of “The Last Living Rose,” a new song that she premiered live last year at the Camp Bestival fest. Why it took so long for a new PJ Harvey song to make its way to someone who considers herself a pretty big fan of the performer in question is a matter that will likely be part of my endless ruminations about the unwieldy nature of “keeping up” in an era where there is simply too much media, and how the resulting glut leads to even the most well-meaning people having their brains overcluttered with minutiae regarding phenomena like 3Oh!3 and Jersey Shore. But for real, I could go on about that for days. (And I really don’t need to trigger any more dreams about Jersey Shore, thanks.) So let’s put that aside for now and enjoy the song, which was apparently written on the Autoharp Peej wielded on White Chalk yet possesses a gritty edge reminiscent of her earliest material. [Via]

Beige, Beige, Baby

“Most people aren’t accustomed to seeing mood lighting. If you’re in a bad mood, the lights will go red, and they’ll go blue if you’re in a good mood… There’s some kind of sensor, like I guess a mood-ring sensor thing. I really don’t know, I still can’t figure out how it works, but it’s amazing. They’re all done in fiber optics. When they’re off, you can’t tell they’re in the house.”

-Guess what Vanilla Ice is up to? Right! He’s renovating houses for resale. He decorates in earth-tones to “keep it neutral, warm and welcoming,” and, apparently, installs magical emotional detectors.

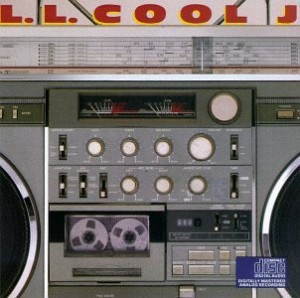

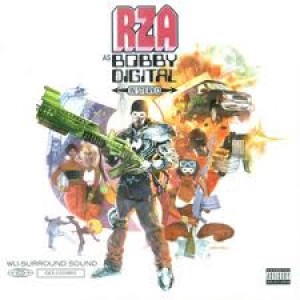

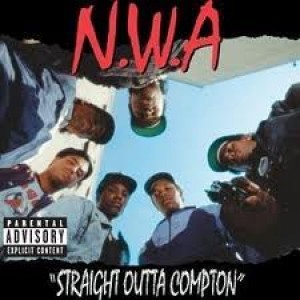

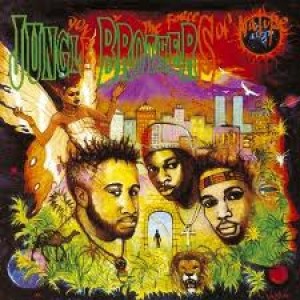

A Tribe Called Quest's 'The Low End Theory' Correctly Named Greatest Hip-Hop Album Cover Of All Time

Complex has an enjoyable slide-show thing up ranking Hip-Hop’s 50 Greatest Album Covers of all time. They awarded the top spot to A Tribe Called Quest’s 1991 classic The Low End Theory. I think that’s just right.

But since this is a list, obviously made to be argued with, I’ll point out that Run-DMC’s King of Rock should have been about 13 spaces higher than its 15th slot.

And Scarface’s Mr. Scarface Is Back should have been maybe no. 3, instead of 19.

And here are a few more covers that I was sorry not to see on there.

Waiting For The End of The (Site Marketing The Movie About The) Affair

I guess in the era of AshleyMadison.com offering to name the Meadowlands’ new football stadium a “viral” site mimicking a blog dedicated to giving the married advice on how to approach their “freebie” that is, their one-night-only chance to Get Out Of Cheating-Partner Jail Free should not surprise. And yet. There is something about the way that Untie The Knot (Tagline: “Just Another WordPress Site”) blends the ineptly marketing-oriented and the semi-servicey that makes me sort of ill. Also, I suspect that a, the movie will be pretty bad, and b, it’s only a matter of time before AshleyMadison makes a “content play” for the mismosh of hastily written blurbs within. [Via]

'Rich People Things': The Movie

Chris Lehmann’s Rich People Things, the book (not the popular column from which it springs), is out today a month from yesterday! If none of our previous entreaties have convinced you to purchase it, perhaps this witty trailer will do the trick. It makes fun of the editors of Wired at one point! Who could fail to be charmed by that? You know what to do.

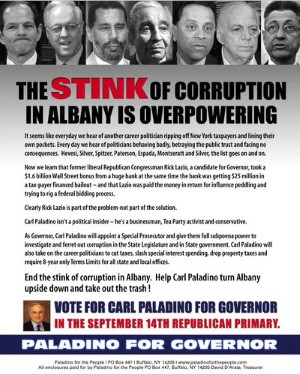

This November, Vote For The Guy Who Made Your Mail Smell Like Shit

Everything may be going to hell, but at least the gubernatorial campaign of Republican Carl Paladino will provide us with plenty of amusement on the way there: “Something stinks in about 200,000 mailboxes around New York — a flier from the new Republican nominee for governor…. ‘Something STINKS in Albany,’ the mailer says. Paladino spokesman Michael Caputo told The Associated Press on Thursday that the mailer is scented with a ‘landfill’ odor. He says the smell will get worse the longer it is exposed, just like Albany.”

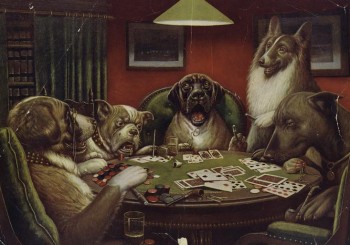

The Global Casino

by Carl Hegelman

A long time ago I was involved in an attempt to finance the buyout of a card club in LA. It was quite a profitable business, doing about $100 million a year in revenues, on which it cleared close to $30 million after cash expenses. They made their money by charging people to sit at a table and play poker, taking a little piece of each hand. That way they could get away with not being a gambling establishment, which would have been illegal in Los Angeles, because they weren’t actually a participant in the game; they were just a venue where people happened to sit down and play a game of skill against one another for money. The people who pitted their wits against one another won or lost, and the owners of the club took their cut and lived the high life.

It’s a long story with enough characters and plots to keep Damon Runyon busy for a good while, but that’s not really the point and it can wait for another time. The point is, our economy is becoming a card club and we really should try to figure out what to do about it.

There are good things and bad things about gambling (or, as Wall Street prefers to call it, “gaming”). On the one hand, people should be allowed to do whatever they want with their money, including blowing it at a card club. Also, it generates jobs: ask all those mini-skirted cocktail waitresses in Las Vegas. On the other hand, is this really a valuable contribution to our economy and society? In aggregate, the players come out losers: only the house makes money; for the rest it’s a negative-sum game. Some people get hurt — viz., the compulsive gamblers who fritter away their paychecks, especially the ones who borrow from the “juice guys” and end up in dumpsters; a very few people, maybe, win.

Still, the majority of reasonable, level-headed people would probably conclude that gambling is a mostly-harmless leisure activity, like bowling or going to a movie. The people who do it aren’t being forced at gun-point. And they pretty much know they’re going to lose a bit of money. That’s the price they pay for the fun of hanging around in a casino hoping they might be one of the lucky ones who hits the jackpot. If a few people get hurt, well, that’s an additional price, just like crash victims are an additional price for allowing people to drive cars or fly in planes, alcoholics are an additional price for allowing people to drink, etc etc. And, after all, how bad can it get? People only have so much discretionary cash to give to casinos. In the US, apparently, we gamble away about $90 billion a year, or about $385 per person for everybody over 18, mostly in casinos (including the Indian kind) and state lotteries.

The thing is, though, these numbers really understate the true size of the casino industry: If a casino is a venue where the punters, in aggregate, always lose and the house always wins, then there’s a much bigger “gaming industry” going around under an assumed name. To wit, the so-called Financial Services industry. The dynamics of the world’s financial markets are very much the same as those of the casino: the more people gamble, the more they lose and the more the house makes. The secret is to keep passing the ice cube from hand to hand and collect the drips. This kind of gambling, because it’s so much bigger, is doing us all a lot of damage. It is not a mostly-harmless leisure-time activity, and it’s one of the things that is ruining our economy.

A lot of people don’t seem to realize the negative-sum nature of, for instance, the stock market. They have the idea that the stock market somehow feeds money to businesses that need it, and that said businesses then hire people and buy machines to produce stuff that we need. This is not true, though it is an impression bankers are in no hurry to correct. The stock market is a place where people who have already invested their money in these businesses can then sell their shares to other people.

It’s obvious, when you think about it. If you buy 1,000 shares of Intel at $20, Intel doesn’t see any of that $20,000. The person who sells you the 1,000 shares is who gets the money. Right? Less, of course, the tiny commission that the brokers get from the seller and the buyer for filling the orders. Oh, and there’s another little charge — the so-called bid-ask spread, which is another small kind of hidden piece the markets take (e.g., you pay $20.00 plus commission; the seller gets $19.99 less commission).

Of course, companies do raise money when they sell new shares, which then get traded on stock exchanges. But let’s put this in perspective. The amount of money raised in the US by companies going public with Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) runs around $40 billion to $45 billion per year. The amount raised in “secondary offerings” by companies already listed on US stock exchanges averages $50 billion to $60 billion. So let’s say around $100 billion a year of new money comes into the US stock exchanges every year. (The banks, by the way, typically take about 7% to sell an IPO; and by some estimates the total cost to the company is more like 15%, because the banks usually under-price the deal to make it easier to sell and collect their commission.)

Now, contrast this number-$100 billion a year-with the amount of stock that people bet on every trading day. On the New York Stock Exchange and the NASDAQ, the amount of stock traded every trading day is around $125 billion. That’s around $32 trillion every year, or $320 for every new dollar actually invested in companies. (And that doesn’t count the increasing amount traded on the “dark pool” private exchanges). None of this money goes to any productive enterprise, it’s just a round-the-clock poker game. The house cut on this volume is much smaller than for an IPO, but it’s not pocket change.

The stock market is just one of the games, don’t forget. There’s a lot of other tables in the global casino. The bond and bank-loan markets are actually a lot better (for the bankers) in some ways, because bond and loan volume is in the trillions of dollars every year and, better still, bonds and loans come due after a relatively short time and most often you need to do new bonds and loans to pay off the old ones. Drip drip. Generally, too, the spreads (the amount taken by the middleman) are higher than for stocks in the trading markets after the deal is done. Then there’s the foreign-exchange market, where $4 trillion changes hands every trading day: that’s the entire US economy in less than four days, the entire world economy every two weeks or so. In all these markets, of course, there are also “derivatives”, which are securities whose price depends on the prices of the stocks, bonds, loans, mortgages, commodities, and currencies in the primary markets: a whole new area for one poker player (or his computer) to face off against another one. Drip drip drip.

It doesn’t help, by the way, that the poker players here (i.e. mutual funds, insurance companies, pension funds, endowment funds, etc) are mostly playing with other people’s money. Letting other people play your poker for you is not a good place to start, as Warren Buffett has explained with his usual clarity and dry wit. Because the “money managers” who bet your money on the markets every day don’t do it for free. They get quite a lot of the drips off the ice cube, too. (And it’s a big ice-cube: institutional investors in the OECD countries manage probably in excess of $40 trillion). This symbiosis of banks with an interest in high volume and “investors” playing with other people’s money is not a formula for wealth creation, at least for the rest of us.

This is not to give the idea that these markets have no useful purpose. In fact, they’re crucial to our system. If we didn’t have big, liquid markets where we could sell our stocks and bonds if we needed to raise cash, we’d be back in the 17th century and nobody would invest in anything. And if we didn’t get “price signals” from these markets showing where the money is best invested, we’d probably invest in all the wrong things (I mean, more often than we actually do, which is quite often-witness the dot-com and other bubbles).

But it’s come to the point where the tail is wagging the dog; in fact, not just wagging the dog but flinging the poor beast about like a rag doll, with potentially disastrous consequences for him. In 1965 the average daily trading volume on the New York Stock Exchange was 6.2 million shares. That’s about 30 second’s worth of trading on the NYSE and NASDAQ today. And it wasn’t like the economy was hurting as a result: the economy was pretty good. In the 1960, the average holding period for US stocks was about eight years; today, it’s more like seven months. The poker players are in a veritable frenzy.

Moving the money around more often doesn’t really benefit anybody except the banks. Why are we doing this? And what can we do to stop it? It’s a complicated subject, and nobody really has the answer yet. Maybe the only consolation is that eventually the banks will own the ice cube and we can all have fun watching them die of cognitive dissonance.

Carl Hegelman (a pen name) is a corporate bond analyst and a connoisseur of leisure.