Odd Lots: Curious Objects Up At Auction

A literary bottle, pigeon diplomas & famous people’s phone numbers

Lot 1: Message on a Bottle

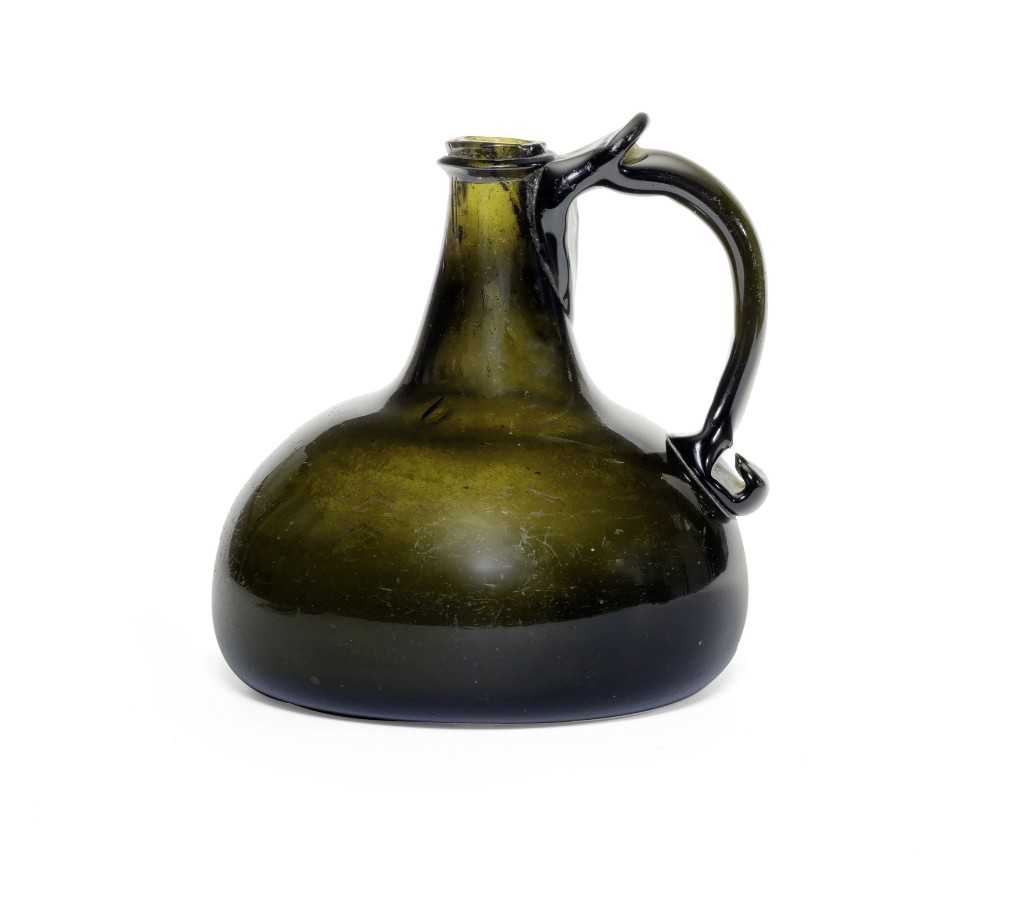

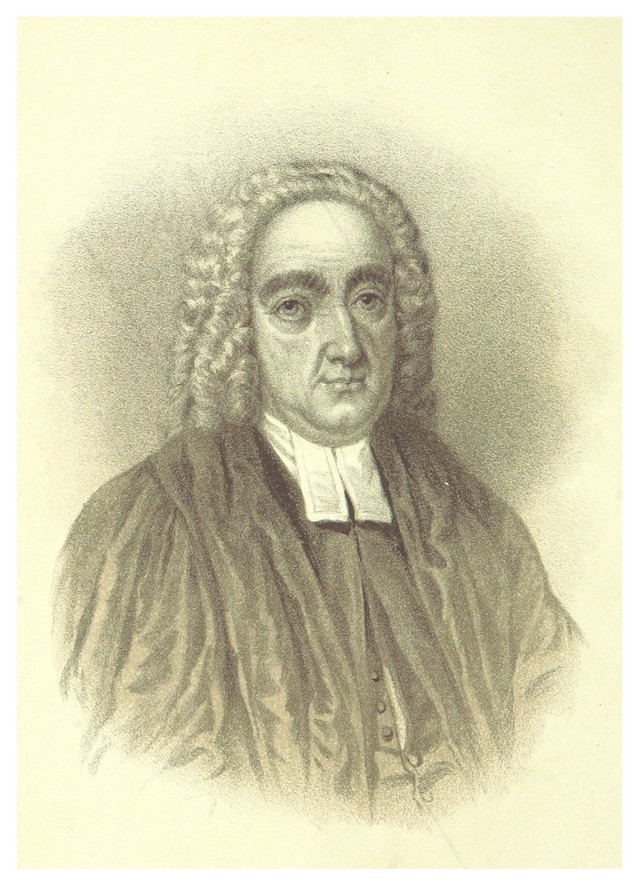

Jonathan Swift, known to all who passed high school English class as the man who wrote Gulliver’s Travels, was also a wine lover. An onion-shaped green glass bottle dating from the early 18th century believed to have belonged to the Irish author has turned up in London, where it heads to auction later this week, estimated to fetch as much as $8,500.

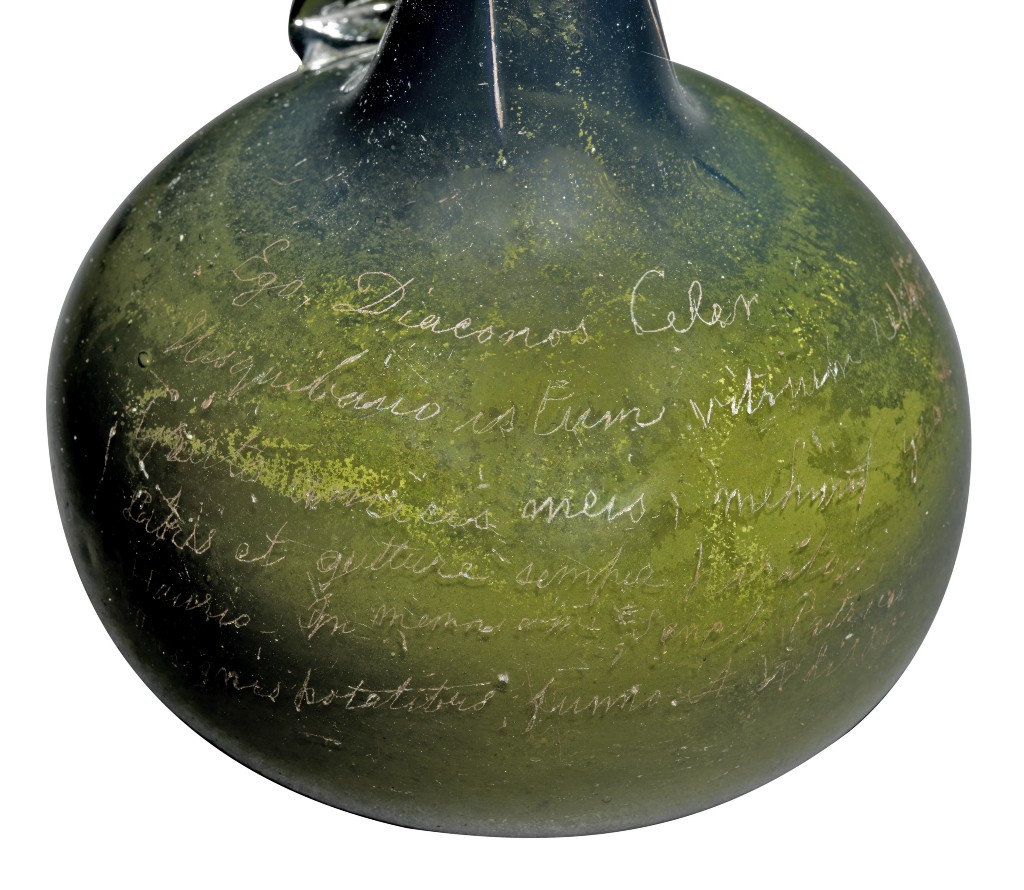

Beguiled by a faux Latin inscription etched right onto the glass, the auctioneers tried their best at translating it, coming up with: ‘I Deacon Swift fill this glass in thanks to my friends and drinking in memory of my homeland with good drinks and whisking smoke.’ Swift was famously fond of wordplay, and the opening phrase, ‘Ego Diaconor Celes,’ is thought to be pun meaning, ‘I Swift Deacon,’ since Swift was, in fact, a deacon of the Irish Church from 1695 until 1713.

The curious text might be interpreted as a toast, or a passive-aggressive ownership statement — he would have appreciated a set of wine glass charms — either way, it appears that Swift poured from this very vessel.

John Sandon, head of ceramics at Bonhams, commented, “This is a very rare bottle in its own right but as we did more research the evidence began to mount that it had once been in the hands of one of Ireland’s greatest writers, Jonathan Swift. There is little doubt in my mind that Swift was the original owner and that it was made to his specification.”

Ironically, Swift drank to cure his vertigo, according to biographer Leo Damrosch. “He ordered six hogsheads a year from France, each containing sixty-three gallons … It was decanted as needed into bottles, and of course often shared with friends.”

Lot 2: Pigeon Diplomas

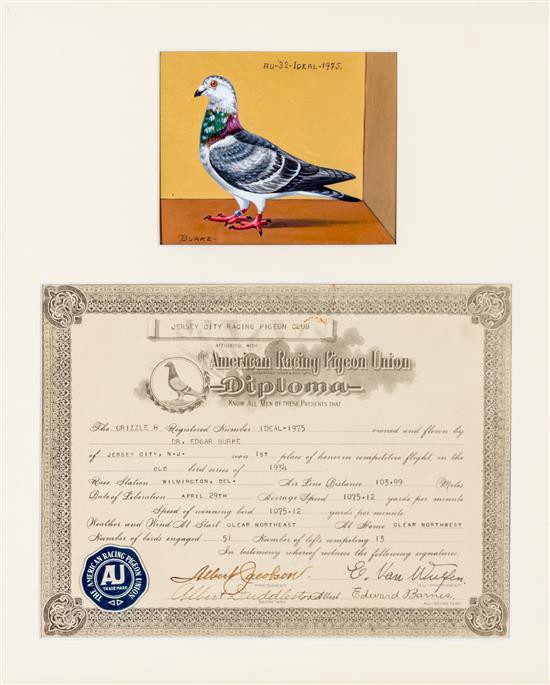

This collection of pigeon art and memorabilia, which goes to auction on November 2, includes twelve gouache-on-board paintings by Dr. Edgar Burke, a New Jersey surgeon and amateur artist, who, having joined the Ideal Racing Pigeon Club in the early 1930s, painted portraits of his prize winners.

Four of the artworks are individually framed and accompanied by a certificate from the American Racing Pigeon Union (still a thing) documenting the race stats, including weather and wind conditions. The bird pictured here won 1st place for his flight from Jersey City, New Jersey, to Wilmington, Delaware, in 1934.

A German-made pigeon race timing clock made by Robert Plasschaert is included. If you’re a pigeon lover, all of this can be yours for $6,000-$8,000.

Lot 3: Bill Cosby’s Phone Number

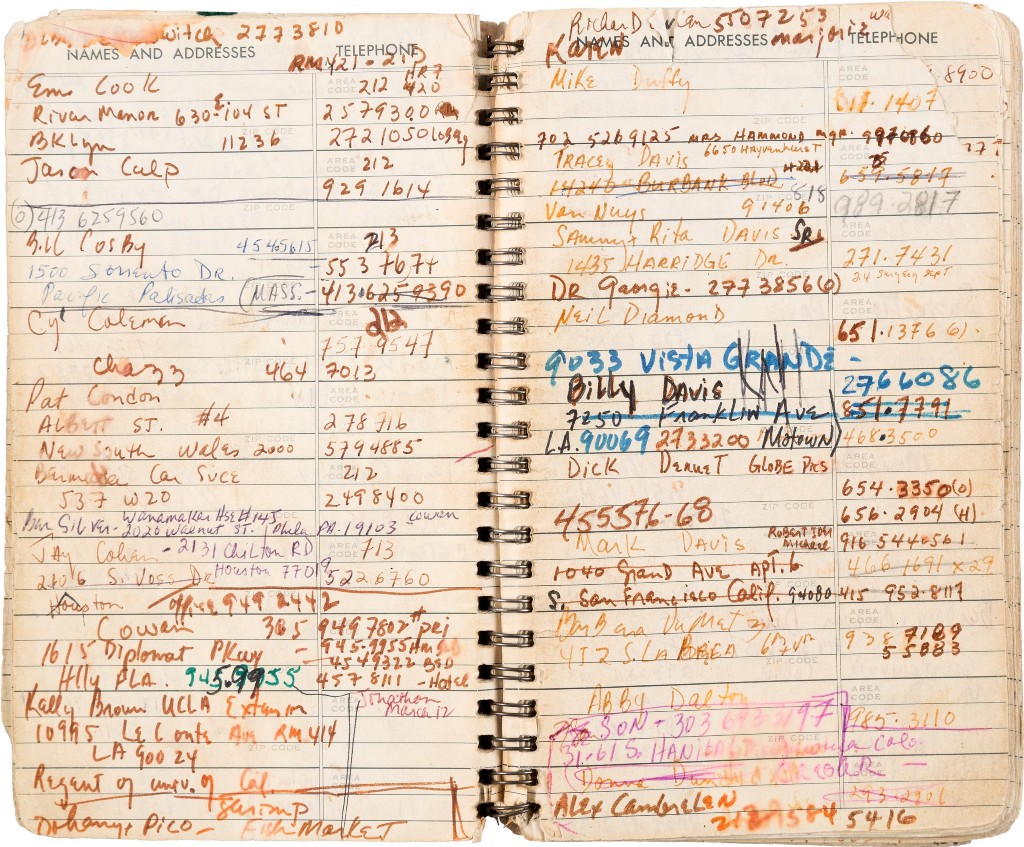

Last, and least: What might we do with Bill Cosby’s phone number? At an entertainment & music memorabilia auction in Dallas on November 12, one of the many offbeat offerings is Sammy Davis Jr.’s address book from the 1980s (he died in 1990). The scribbled-in spiral-bound notebook is chock-full of names and numbers in various inks and hands — “likely secretaries, though some in the star’s own hand,” according to Heritage Auctions. The bidding opened online at $500.

We could rattle off the A-listers within — Clint Eastwood, Michael Jackson, Richard Pryor, Frank Sinatra (duh), and Barbra Streisand — but in the image seen here, obviously the C-D section, note Cosby in the upper left. Also, Neil Diamond.

Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places.

You Do Not Need to Tell Me You Are Engaged to Your Best Friend

Expanding your social media vocabulary

Sometimes, fam, good things happen in our lives and we post about them online. And when we do, there is a word bank of stock language we tend to pull from. Things like promotions at work, pregnancies, and moving to a new city can all inspire us to use our accounts for an impromptu press conference when we’re usually on there asking for overnight oats recipes and posting screenshots of 4:20 p.m. Today I would like to talk to you about engagement announcements in particular.

I personally have never been engaged to be married, but having been online more than once, I have osmosed enough wedding industrial culture to fart out a Mad Lib engagement announcement if I try. Look:

Welp, it’s official! As of [recent date], we’re getting married! I cannot believe how [lucky/excited/honored] I am to be [marrying/spending the rest of my life/sharing my greatest adventure with] my best friend.

Here is the thing: I get it. Your partner is your favorite person and you feel strongly about this. So strongly, in fact, that you are willing to commit to spending a lifetime with them. Arguably, it’s one of the strongest feelings out there, and given these context clues, it’s not difficult to deduce that you might consider this person a friend. Perhaps, even, a close one. Now obviously there are tons of marriage models out there and not all of them are friendship-based—maybe you are hoping to indicate that your marriage is not arranged, or that your pairing is somehow different than others in your family. That’s great! But you can still do better than best friend.

When you sit down to write about your beloved, “What have I seen other people post online?” is not the best prompt. Don’t adopt the tone of the form, don’t mimic the occasion-appropriate language you’ve seen cement mixed and repurposed and recycled through feed after feed for ten years. If it’s vague but upbeat enough that you could also be writing about your Subaru Forester, you’re not doing your best work. Instead, maybe think, “Why am I, specifically, excited to marry my partner, specifically?” You consider them a best friend. What does that look like? What does that act like? What does that sound like after a shitty Wednesday at work? Your partner probably rules and shows up for you in all kinds of ways. You can do better for them than “friend.”

And listen, it’s your feed. You’re allowed to post on it however you want. But if you’re posting about how special someone is to you and how specific of a feeling that is, you probably shouldn’t be leaning on the kickstand of language you’ve ingested and digested and pooped out 70 million times already. We know you like your partner—you’re marrying them! Just tell us you’re happy in your own goddang voice and trust that that is enough. Then let us congratulate you.

Lambchop, "NIV"

10,000 more minutes, give or take.

As of 11 AM this morning there are 180 hours remaining until polls close out in California, ending the 2016 Presidential Election. (If we’re lucky. Which we have not been so far. So who even knows.) Basically, if you watch the full run of “The Sopranos” twice you’re through it, although you personally will not be fortunate enough to cut to black at the end. Anyway, it’s November. It’s the last Tuesday before the Tuesday. There can only be five or so surprises left that make you want to smash your head in with a heavy object. Think of it this way: After what this year has done to us everyone will be so beaten and numb at Thanksgiving that those 6 hours will pass by in blessed silence. (If you figure 6 hours for Thanksgiving there are roughly 30 Thanksgivings until the polls close.)

But let’s talk about something happy. The new Lambchop album FLOTUS is the best thing they’ve done in several years, and they weren’t even a band that was coasting or anything. Here’s “NIV.”

And here’s Lambchop’s Kurt Wagner on the album’s origins.

FLOTUS or For Love Often Turns Us Still

FLOTUS is out Friday. Enjoy.

New York City, October 30, 2016

★★★An enchanted or murky haze caught the sunlight and held it. It was too warm out for even the lightest jacket; people were stripping down. Pigeons crowded around a filthy pothole puddle to bathe in the opaque water, fluffing and stretching. The afternoon turned browner. One tipped-out window in the darkening glass of the tower across the avenue still caught the light. Very grim and very low clouds dragged across the sky from the north, and the five-year-old demanded the window be closed. Oncoming rain blurred the river. The figures who’d been out in the warmth on the roofdeck huddled and then dispersed. People stood at their windows to watch the first wave blow through. Within the hour it had gone away and tentative light patches were appearing, but along with the night came audible thunder.

The Worst Holidays To Have A Birthday On, Ranked

A listicle without commentary

17. Thanksgiving

16. New Year’s Eve

15. Halloween

14. Summer

13. Valentine’s Day

12. Mothers’/Fathers’ Day

11. Independence Day

10. Cinco de Mayo

9. St. Patrick’s Day

8. Veterans’ Day/Corduroy Day

7. Yom Kippur

6. Columbus Day

5. Christmas Eve

4. Christmas Day

3. April Fools’

2. New Year’s Day

How To Keep Off The Internet

You’re not going to like it, but could you really be less happy than you are now?

I try my best to understand those in whom the inability to avoid the Internet is so irremediable that they need outside assistance to prevent themselves from seeing what idiot meme, poorly constructed argument or distressingly predictable thinkpiece is making the rounds at any given moment. My sympathy is best engendered by remembering that the atomizing nature of modern existence leaves many of us bereft of emotion, so anything that engenders a reaction — even one of anger or disgust — offers an ineluctable appeal to those who have been inured to passion and are desperate simply to feel, no matter how cheaply.

I suppose telling people to just stay off the Internet is a lot like telling an alcoholic to just not drink, except with alcohol at least there is the sweet relief of pleasure as your body grows warmer and everything around you becomes more pleasant, your cares drifting away while your ability to find joy in even the most unlikely of circumstances is so greatly improved that the saddest of situations can still be an excuse for celebration. Oh my God, alcohol is the best, I’m sorry I compared it to the Internet — a cold, lifeless mass made solely of spiky edges that only makes you feel worse about yourself and everyone around you.

Anyway, my point was there are things you can do to keep yourself away from the Internet if your willpower is lacking or your degree of self-loathing is so large that you subconsciously seek punishment by subjecting yourself to the horrors online all the time. There are a number of solutions here, or you could try this real-life low-tech aversion therapy solution: Each time you want to look at the Internet, stick your dick in a drawer and slam it shut. (Here is where you might say, but what if I don’t have a dick? Good news: This exercise is unnecessary for you because not having a dick you start off not being a fucking idiot, plus society has conditioned you to feel unpleasant about something at all times, so you can just make that your Internet-going-on equivalent.) If after a few sessions you are still tempted, take a Sharpie and write the words “The Internet” on a hammer and the words “me and my will to live” on your balls and then smash the latter with the former. (Born without balls? See above.) If after all of this you still can’t keep away from the Internet I have a solution involving wet fingers and light sockets but that is really such an advanced-level class that I feel uncomfortable giving away its secrets to just anyone. Follow me on Twitter and subscribe to my Tiny Letter for more.

The Jack the Ripper Content Economy

The murders that will never be solved by selling a lot of books

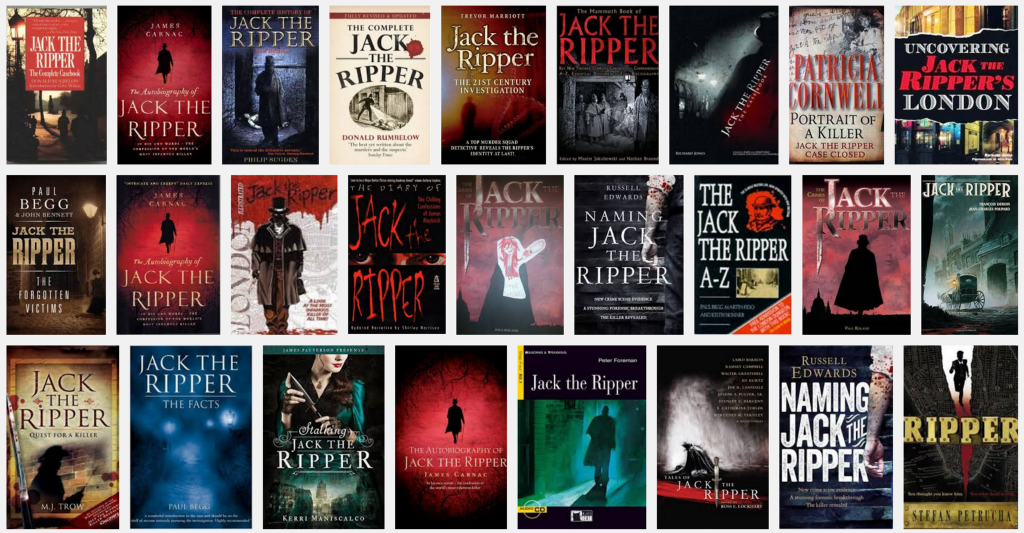

This fall marks the 128th anniversary of a series of murders in London’s Whitechapel district — at least five, for sure — that have long transformed from an investigation to a vague romantic aura that haunts the more macabre corners of pop culture. The case is more frostbitten than cold: due to a combination of muddled evidence and the deteriorating effects of time, the case will never be solved. Yet despite the lack of leads — in fact, because of them — the content business of Jack the Ripper is still booming.

An Amazon search spits back nearly 4,500 items, IMDb returns 119 TV episodes or movies, but even those numbers don’t account for the subtly titled video games, websites, stage plays, operas, paintings, radio dramas, songs, costumes, or various Etsy crafts that seek to capture that “Jack the Ripper aesthetic.” You know it: that sinister silhouette with top hat and cane, sounds of raindrops and horse hooves echoing on candlelit cobblestones, frantic police whistles in the dark followed by cries that they found another. Jack the Ripper is a perpetual content machine from beyond the grave.

As all brands do, it started with a name. Before he was officially christened, newspapers referred to the killer as either the “Whitechapel Murderer” or “Leather Apron,” taken from a clothing item worn by a suspicious person police wanted for questioning. But on October 1st, 1888, London’s Metropolitan Police released a letter that had been previously received by the city’s Central News Agency. It was signed:

Yours truly,

Jack the Ripper

Dont mind me giving the trade name

Why this single letter — of the dozens claiming to be from the killer — was given legitimacy is unclear. It was received on September 27th, three days before the infamous “double event” — the Ripper’s first two victims were found on August 31st (Mary Ann Nichols) and September 8th (Annie Chapman) and then two (Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes) were found on September 30th; the fifth known victim, Mary Jane Kelly, was found later, on November 9th — and it referenced cutting “the ladys ears off”; Eddowes was found with her right earlobe severed. That similarity was good enough for the cops, even though it was subsequently proven a hoax when another letter surfaced with different handwriting and spelling, but further legitimized because it also came with a human kidney, allegedly from the body of Eddowes. No matter; the brand had been established. The media frenzy now had a name to latch onto.

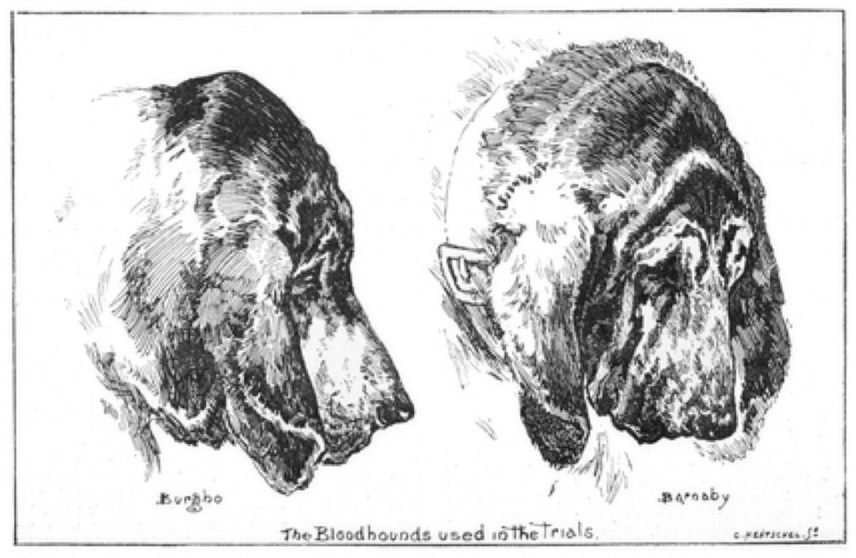

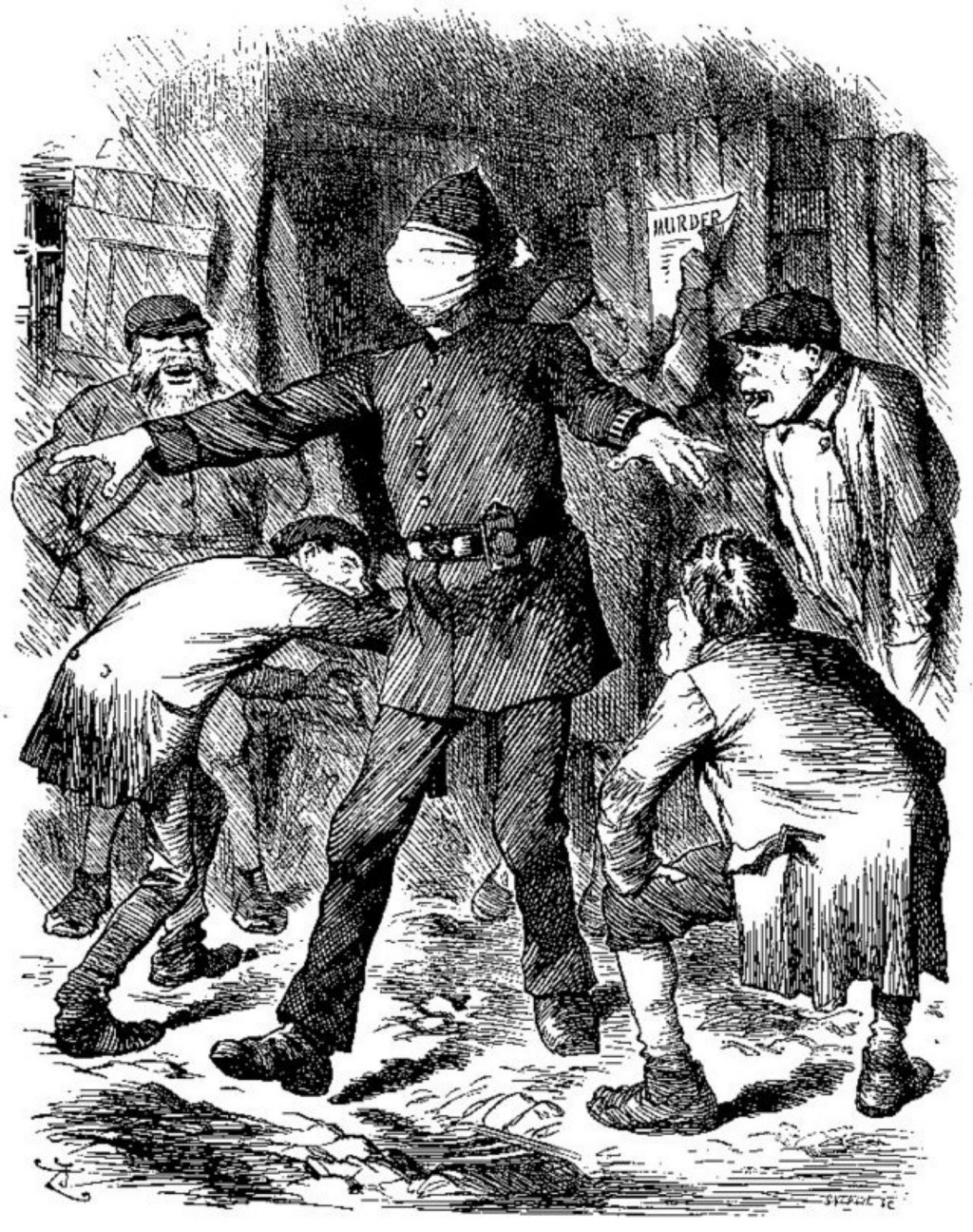

Newspapers like The Penny Illustrated Paper and Punch sold like whatever the nineteenth-century British equivalent of a hotcake was. They’d have the latest details: maps of murder sites, sketches of suspects and victims (some gory, some angelic), inquest transcripts, even the blow-by-blow of the heavily mocked sniff-hunt through London’s parks by the police commissioner’s two bloodhounds, Burgho and Barnaby. It was a worldwide media sensation, with readers as far flung as Mexico and Jamaica clamoring for coverage. But as the murders dried up over the next few months (at least those gruesome enough and without obvious suspects), the column inches of 1889 were commandeered by other worries of the day. Even the coverage of the Ripper case itself shifted, from being a story about a string of gory murders, to focusing on the plight of those living in the squalid conditions of London’s East End; there’s a pretty direct line from Ripper coverage to the stirring of socialist sentiment and ultimate creation of Britain’s Independent Labour Party in 1893.

The Ripper News Mill sputtered to life again in March 1903, when former London Metropolitan Chief Inspector Frederick Abberline told the Pall Mall Gazette that his favorite suspect (George Chapman, birth name Severin Klosowski) had been convicted of murdering three women with poison and set to hang. But even interest in that thread soon dissolved among the other claims, leaving newspapers with only scraps of rumors, anniversaries, old man memoirs, retirement notices, and, finally, short mentions in the obituaries of ancillary players.

Any era’s aesthetic becomes commodity as the past drifts backwards in time, but the massive changes to everyday life in the early twentieth century — say, the widespread use of electricity that merged day and night into a single waking nightmare — provided folks with plenty of reason to be nostalgic for the Victorian era. Into this seedbed blossomed renewed interest in the serialized Sherlock Holmes, gothic books like The Curious Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and stories about this vague evil character named Jack the Ripper, no longer a real-life serial killer still on the loose, now only a murky shadowy spook that authors could use to spice up their stories. While actual news evaporated, the Ripper brand flourished like a franchise. Fictionalized accounts had been published from the get-go — the earliest being John Francis Brewer’s The Curse Upon Mitre Square, published in October of 1888, while the murders were still taking place.

In 1907, German publishing house Verlagshaus für Volksliteratur und Kunst published the thirty-two-page dime-store novel How Jack the Ripper was Taken, the first to take the logical step of pitting Sherlock Holmes against Jack the Ripper. In 1913, Marie Belloc Lowndes published The Lodger, in which a London couple suspect that the mysterious stranger staying in their upstairs room is actually the murderer. (A 1927 film adaptation of the novel was Alfred Hitchcock’s first hit.) Leonard Matters blurred the lines in 1926 with The Mystery of Jack the Ripper, the first non-fiction “serious examination” that recounted a deathbed confession from Dr. Stanley, a pseudonymous doctor who claimed he’d committed the crimes as revenge for his son, who’d died of syphilis contracted by a sex worker. It was obvious bullshit, more Blair Witch-style salesmanship than anything else, but it was the first in the Ripper whack solution sub-genre, trotting out unverified claims as indisputable solutions. In 1943, Robert Bloch, the horror/sci-fi master who’d yet to write his novel Psycho, turned the murderer into an immortal who killed to remain so in his short story “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.”

Soon the Ripper achieved full cliché status, appearing in stage plays and operas, radio dramatizations and film, always donning the romanticized gear of top hat, black cape, and walking cane (a polished look that the real killer, likely a resident of the poorest neighborhood in London, most certainly didn’t have). But it was these depictions that, oddly, fueled the next phase of Ripper Content, which simultaneously pushed back against fictionalized hype while doubling down on the false aristocratic aesthetic.

In 1970, a surgeon named Thomas E.A. Stowell wrote an article titled “Jack the Ripper — A Solution?” for the quarterly crime magazine The Criminologist. Ultimately, this short piece had two important things going for it: it attracted tabloid sensationalism by claiming a “Royal conspiracy,” wherein the Ripper was actually Queen Victoria’s grandson, Prince Albert Victor; and Stowell died within a month of the piece being published, in the middle of a media blitz. The BBC ran a popular six-episode miniseries in 1973 that retold the Jack the Ripper case through a weird (innovative?) combination of present-day fictional investigators and dramatized recreations; the final episode dipped its toe into Stowell’s royal conspiracy theory. Journalist Stephen Knight saw the show and decided to poke his nose around some more.

In 1976, the twenty-five-year-old Knight came out with Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, a 284-page investigation that unveiled the grand conspiracy between royal family, the Freemasons, and painter Walter Sickert, all to keep Prince Albert safe from prosecution for his grisly deeds. Despite Knight’s main source later claiming that his testimony was all a hoax, as well as the glaring logic holes if one merely glanced at the evidence presented at face value, Knight’s tale was just the right mix of murder, bluster, celebrity, and sensationalism. It was predictably a smashing success. The book necessitated twenty editions and thrust Knight into the media spotlight: The Ripperologist was born.

At this point, there was a schism in Ripper Content. There was the continuation of Ripper Entertainment as generic gothic madman — a dark silhouette to be trotted out during the Halloween season or as a walking horror movie trope. But there was also the rise of “serious examinations” into the case, as a kind of counterstrike against the popular acceptance of the bullshit claims from Knight, who died in 1985 from a brain tumor. The Complete Jack the Ripper, Donald Rumbelow’s account of the case first published in 1975, was now continuously revised and republished. Philip Sugden compiled more case facts for The Complete History of Jack the Ripper in 1994, the same year Paul Begg’s Ripperologist magazine began printing sixty-two pages of brand-spanking-new Ripper Content every other month. Stewart Evans and Keith Skinner combed through the Metropolitan Police archives and published weighty volumes of source materials, from a compilation of every letter the police received claiming to be from the murderer, to a 750-page illustrated encyclopedia of the case’s written records. (On the entertainment side of things, writer Alan Moore and artist Eddie Campbell developed the graphic novel From Hell, between 1989 and 1996, based in part on Stephen Knight’s royal conspiracy; Johnny Depp was later in an awful Hughes Brothers movie that was loosely based on it.)

Ripper Content finally went online in 1996, when Stephen Ryder created Casebook.org as a clearinghouse for it all. There are crime scene details, witness testimony, victim and suspect dossiers, reviews of every fiction or nonfiction book that’s ever been printed, a searchable index of Ripperologist magazines, and even a still-active message board, where users from around the world congregate to lob solutions and debate over non-canonical victims, 24/7. This being Web two-point-whatever, there’s also a section for podcasts.

The rise of legally admissible DNA evidence was obvious fuel for the next generation of Ripper Content. In 2002, bestselling crime novelist Patricia Cornwell’s Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper — Case Closed offered irrefutable DNA proof that painter Walter Sickert could not be ruled out as a suspect in the writing of a few Ripper letters. Read that sentence again to find the holes in her claim. Despite it being obvious pseudoscience standing on the shoulders of baseless accusations, with a name attached like Cornwell’s — who, as every press release noted, sold over 100 million copies of her Scarpetta novels — the popular media latched on. Book-release hype masked as real news culminated in an hour-long TV special on A&E that features easily my personal favorite moment of Ripper Content: This hilariously awkward heist-movie montage of Cornwell walking to the Public Records Office with her “team of experts,” all set to a kickass Radiohead bassline.

The Ripper Content’s whack solution sub-niche never really went away, Cornwell just gave it new life through financial relevance. Each book-length whack solution release takes the same general journey. They’re first-person accounts that begin with the author becoming obsessed with the case, which allows for a re-telling of the same basic facts everyone knows by now. But then (then!), the author stumbles upon some contradiction, or missing link, or a clue that nags at them and forces them to examine further. That leads them right to the doorstep of their suspect. Except all the suspects are dead. The rest of the book becomes a sleight-of-hand act, trying to link their suspect to the murders without overt shoehorning, a deft backwards compatibility that’s easy to spot once you know how to look for it.

The latest popular attempt of finding a solution is They All Love Jack, a sprawling (read: rambling) 864-pager released late last year by filmmaker Bruce Robinson, best known for Withnail and I. Robinson names Michael Maybrick, traveling musician brother of previous suspect James Maybrick, as the Ripper with a heaping helping of proof that is, let’s say, not so great? But the most interesting part of the book comes early, in a chapter called “A Conspiracy of Bafflement,” where Robinson scorches the trail cleared by the Ripper researchers who went before. He calls Knight’s book “a well-presented dissertation of comprehensive nonsense” and “a twerp history. (Awesomely phrased owns, but par for the course in terms of criticism; Knight is low-hanging fruit by now.) Robinson goes on to criticize the entire landscape of “serious examination” Ripper Content created since, mocking the Ripperologists as ineptly gullible, casting the lot of them as doofus blokes in a false flag operation. It’s fun.

While Robinson’s book garnered what may seem like a shift in the tone, it’s really just a blend of the two types of Ripper Content that exist: “serious examination” and entertainment. In fact, any new serious examination of the case can’t really be all far apart anymore from the other Ripper entertainment out there, the video games, or BBC’s Ripper Street, or the baseball team that tried to call itself The Rippers. Or the forty or so Ripper Walk tours throughout London that take tourists over the same cobblestones and into the same bars where the murderer and his victims stalked so long ago; one tour tries to set itself apart with a projection set up that it brands “Ripper Vision.” It’s macabre, but it’s okay. It’s fun!

Last year, the Jack the Ripper Museum opened in London. It has five floors of recreations — See Mary Kelly’s bedroom! See an old-timey mortuary! — and it bills itself as a “serious examination” of the crimes. This, despite the museum hiring actors to traipse around in that erroneous top hat and cape look. It all fits the macabre tradition of horror attractions like The London Dungeon, which, fair enough, but the museum really, utterly biffed its opening. While under construction, the museum’s director sold the prospect of the new installation to the public as “the first women’s museum in London,” with photos of suffragettes and Asian women protesting racist murders in the 1970s included in the planning application. But when the boards were removed for the museum’s opening, its goal had evidently changed to focus on Jack the Ripper. Last Halloween, they even offered “selfies” near victims’ corpses. In the face of mounting criticism, their PR flack claimed the murders — of women, of prostitutes, with genitals slashed — were not technically “sexual violence.” It was not a great look. Boisterous protests accompanied a petition to close down the museum. A year later, the unrest has died down and it’s still open. With nearly 300 reviews on TripAdvisor, the museum has a four-star rating; the word “fun” pops up in at least thirteen. But was this outcry finally evidence we’re getting tired of Ripper Content?

After all, it is a case that will never be solved. Any suspects are long dead, along with their children, and their children’s children; punishment and closure are no longer possible. Even the basic facts of the case are up for dispute. Not only do people have difficulty agreeing on exactly how many victims there were, there’s a question of whether or not there was a lone killer at all and the police weren’t just confused. The best theory to that end was first put forth in 1910 by Scotland Yard officer Sir Robert Anderson, and supposes a set of unrelated female murders and a journalist trying to bring publicity to the impoverished region, not unlike McNulty’s gambit in season five of The Wire.

Besides, no matter the proof attached to it — confession, DNA, some weirdo walking out of a time machine saying in a Cockney accent, “I did it, and this is how” — any “solution” will be widely and enthusiastically disputed as fake. Too many businesses have stock in the idea of Jack the Ripper as vague murderous wraith to allow a true solution to destroy their moneymaker. The Ripper Content beast needs to be fed, debunking keeps us hungry. More than a century after the murders, there’s no place left for “serious examinations” to pin down the killer. Any billing for legitimacy is really just a veiled excuse to dwell in the world’s most popularly-accepted snuff material. The killer got away. All that’s left is the gross entertainment.

Rick Paulas likes Halloween. He previously examined America’s ghost tour industry and the online market for haunted items.

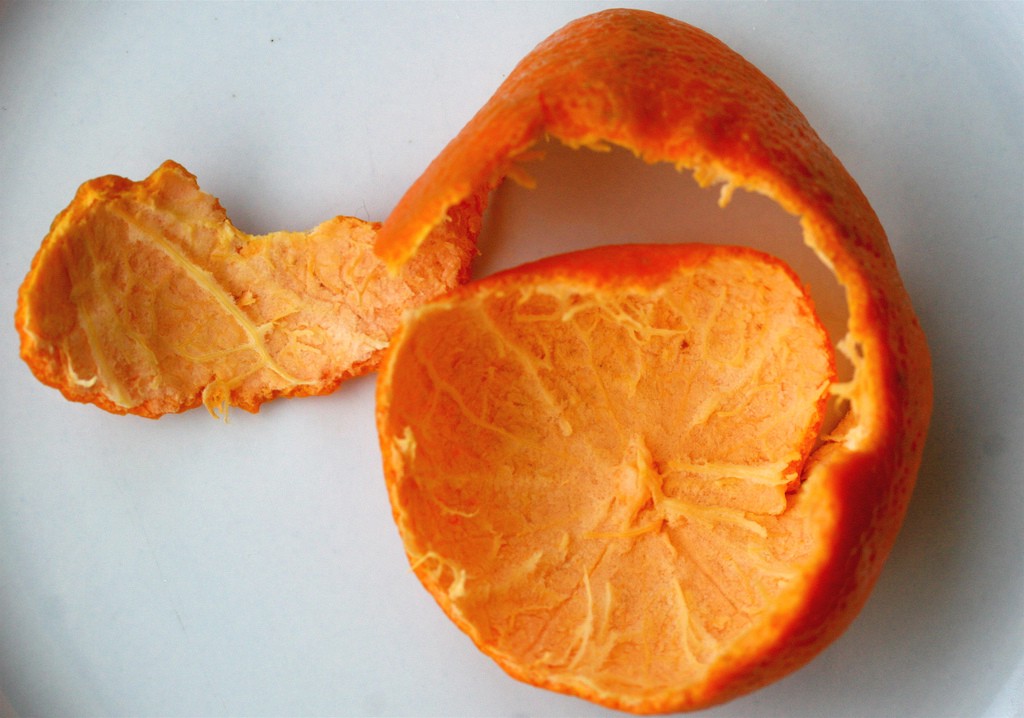

Orange You Glad I Didn't Say Trump?

Rating other famous orange characters, on a scale of 1 to Donald

Between the jack-o-lanterns, fall leaves, artificially-colored seasonal lattes and motherfucking decorative gourd season, this is typically the most orange-hued time of year. But thanks to the sniffling, saffron-skinned standard-bearer for the GOP, we are awash in even more orange than usual this fall. Say what you will, Trump is certainly the candidate most inspired by Hamilton.* In celebration of this unusual Election Day/Halloween crossover, and in honor of the 50th anniversary of It’s The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown (first aired October 1966) here’s a list of famous orange personas, rated on a scale of Trump-to-10, based on how closely aligned in pigment and temperament they are to The Donald.

The Human Torch/The Thing: Both orange members of the Fantastic Four (“just fantastic. So great…”) gained their powers by accident (much the same way Trump came upon his family fortune). Both have catchphrases that could easily work for Trump: The Human Torch’s “Flame on!” would be perfect for Trump’s 3am tweetstorms (the Torch’s real name is Johnny Storm, after all), and The Thing’s “It’s clobberin’ time!” is actually Trump’s secret plan to defeat ISIS — not in a nutshell, but in its entirety. 😡😡😡😡

Annoying Orange: The obnoxious star of the eponymous, hugely popular web series frequently mocks his fellow fruit cart denizens, and, like Trump, gives them demeaning nicknames (Apefruit, Plumpkin, Midget Apple, etc…). He engages in constant attention-seeking behavior, tells offensive jokes and imitates bodily functions.

“Hey Turd!”

“It’s Ted.”

“Hey Ted! Hey, hey Ted!”

“WHAT??”

“Wife!”

“What?”

“Wife! Mine’s hotter than yours! Now get back to the phone banks, Turd! Ha ha ha ha ha…” 😡😡😡😡😡😡😡😡

Scott Thompson — aka Carrot Top: Like Trump, the ginger Gallagher keeps us wondering what ridiculous thing he’ll pull out next from his bag of tricks. Also, in an interview earlier this year (with noted VJ/Fox journalist Kennedy), Carrot Top said he believed Trump was good for politics the way McEnroe was good for tennis: temper tantrums not only make for good TV, they disrupt the status quo. Then he pulled out a pair of “Chris Christie skinny jeans” (a tiny pair of jeans glued onto an XXL pair of pants). Hilarious! 😡😡😡😡

Tony The Tiger: MAKE AMERICA GRRRRREAT AGAIN! It doesn’t matter if his cereal lacks marshmallows or colorful pebbles or chocolatey/fruity flavors or anything that would remotely lift it above the mediocre bowl of sugary Special K that it actually is. Tony and Trump live in a tautological fantasy of their own creation — Frosted Flakes are great because Tony says they are great — orange finger emphatically swooped skyward to emphasize their obvious (to him) superiority. 😡😡😡😡😡

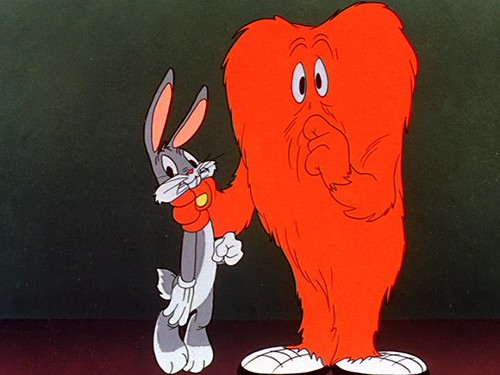

The Monster — aka Gossamer: This curious orange giant first appeared in a 1946 Chuck Jones classic, “A Hair-Raising Hare,” a cartoon where even Bugs Bunny turns misogynist (“That’s the trouble with some dames. Kiss ’em and they fall apart.”) Wikipedia describes the Monster thusly: “The word “gossamer” means any sort of thin, fragile, transparent material…The name is meant to be ironic, since the character is large, menacing, and destructive.” Gossamer is ultimately undone by his vain insecurity about his fingers, and by his sudden realization that an audience is watching and evaluating his every move. 😡😡😡

Garfield: Fat, sadistic, self-indulgent, and smug. This also describes Garfield. 😡😡😡😡😡😡

Chester Cheetah: It was Republican political strategist Rick Wilson who most famously compared Trump to the dusty orange snack food, as he railed against members of the RNC back in June for not renouncing their “Cheeto Jesus,” despite all his obvious (and destructive) shortcomings. Nearly ten years ago, Cheetos created an adult-targeted campaign with a rebooted, “dangerously cheesy” Chester Cheetah. As Slate contributor Seth Stevenson noted back in 2008, the new ads feature a “sinister tone, and, above all, Chester’s cruel insouciance.” Chester encourages his followers to play cruel jokes on their friends and family, and has “evolved into a complex character, one with mysteriously dark motives…[who is] prodding us to do ill to our fellow man…” Visitors to Chester’s webpage (orangeunderground.com) are greeted with the message, “Welcome. My homepage is your homepage. Except it’s about me and all the great stuff I do.” Swap out “campaign” for “homepage” and the Cheeto Jesus has risen. 😡😡😡😡😡

Oompah Loompas: I have a theory: Trump is actually the illicit love-child of Willy Wonka and an oompa loompa. This would explain his orange skin tone, crazy hair, and personality: He gets his manipulative cruel streak, penchant for naming products after himself, and insane detachment from reality from his candyman father, and develops his id-driven/playboy persona in reaction to the incessant (musical) moralizing of his oompa-loompa mother. 😡😡😡😡😡😡😡

The Great Pumpkin: Come election day, Republicans may realize too late that, like Sally, they were hoodwinked into giving up all their candy for a chance to revel in the mythic glory of The Great Pumpkin. As Linus — I mean Priebus — fights for his professional life, he will somehow try to convince his base — their heads bowed like a sad Charlie Brown — that there’s always next year, if they just believe a little harder. In the mean time, I hope they enjoy their bag of rocks. 😡😡😡😡😡😡😡😡😡😡

Eric Schulmiller has written humorous pieces for McSweeney’s and The New Yorker, and on culture for The New York Times Magazine, The Atlantic, Slate, and The Forward. You can follow him on twitter at @wwhipster

Eye Contact

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s cartoons appear regularly in The New Yorker. Her book is A Bintel Brief. This cartoon strip is a spin-off of her Instagram feed, @lianafinck.

How Will You Act When Your Favorite Celebrity Enters the Room?

Will you sit on him?

Let’s say you’re sitting in your family room. It’s Friday night and you’re winding down by chewing on a plush figurine of your favorite international celebrity, when through the door walks that same international celebrity in the flesh.

Could it be?

Maybe you approach him calmly, like a Jane Austen character who has spotted another Jane Austen character from across the dance floor at The Grand Ball. “Hello, sir,” your face might say. “Could you be a Tinseltown icon like I suspect you are?”

And maybe when you get close enough to smell him, he smells like… your loved one. The celebrity is fam, just like you secretly suspected when you were watching him on TV! You let your emotions get the better of you for a second. You hug him. You do a little dance around him. You sit on his chest and pin him there while your friend watches nearby, not quite getting it. This is like reuniting with a lost twin. Or accidentally meeting your birth father.

An icon! A legend! A star! In your house!

Or maybe you won’t greet him like this when the time comes, but it’s good to know that you could.