Baby, You're A Firework

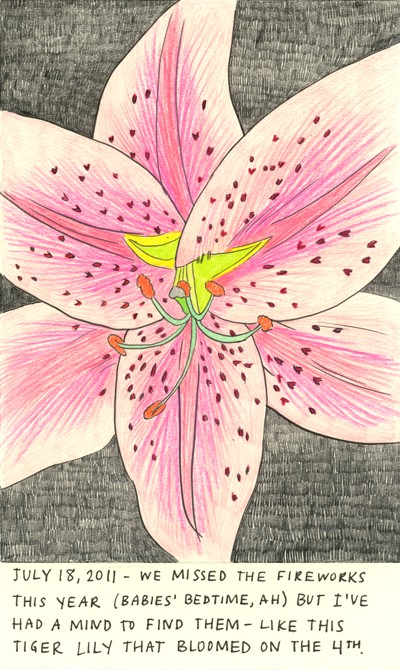

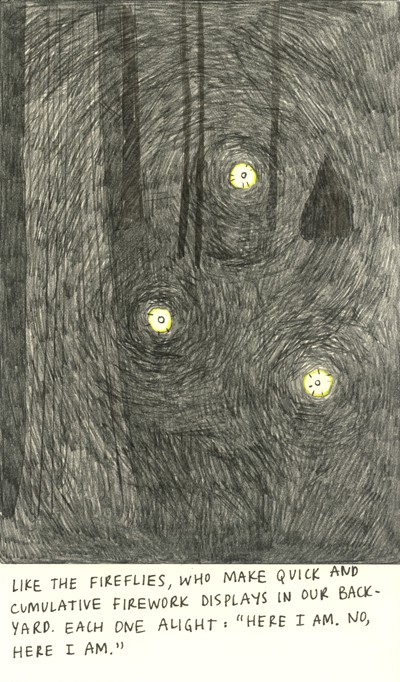

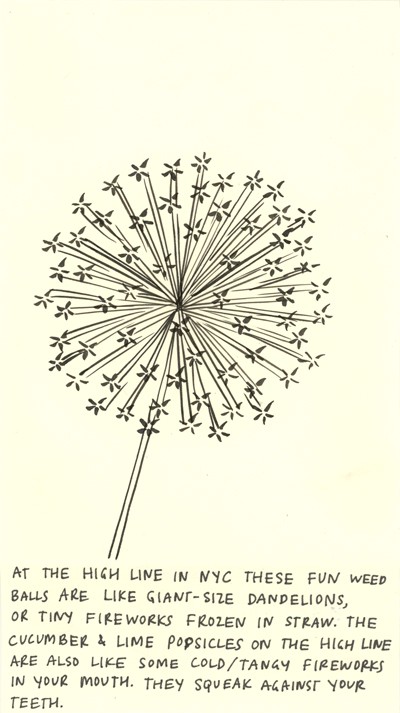

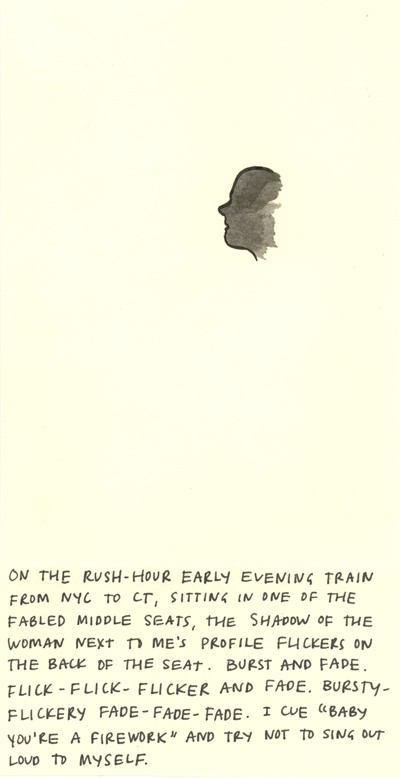

Baby, You’re A Firework

Amy Jean Porter’s first book, Of Lamb, a collaboration with the poet Matthea Harvey, was just recently published. Her show at P.P.O.W. Gallery in Manhattan is up through this Friday, July 22.

Scientists Discover Happy Teens

“Teens who maintain a positive outlook are more likely than unhappy teens to grow into healthy adults, with a better overall state of well-being, according to a new study. Researchers at Northwestern University reached that conclusion after reviewing data collected from 10,147 teenagers who took part in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, which began surveying them in 1994. The teens answered a series of questions in 1994, 1996 and 2001 regarding their physical and emotional health…. The participants who’d indicated that they were happy teens were less likely than unhappy teens to become young adults engaged in unhealthy behaviors, such as smoking, binge drinking or eating unhealthy food, the researchers found.”

— Science has proved conclusively that happy = boring. Now you know!

Photo by D Sharon Pruitt

Facebook as a Threat to Storytelling

Here’s a good question: what if the discomfort expressed, on different fronts and with rationales, by the Malcolm Gladwells and Bill Kellers and the Zadie Smiths and whoever else hates the Face-Twitters now, was mostly just a love of (or addiction to?) narrative? Facebook stories don’t really have any endings, and neither do they always have multiple conflicting sources (not like the newspapers have much of that either anyway). “At the end of every magazine article, before the “■,” is the quote from the general in Afghanistan that ties everything together. The evening news segment concludes by showing the secretary of State getting back onto her helicopter. There’s the kiss, the kicker, the snappy comeback, the defused bomb. The Epiphanator transmits them all. It promises that things are orderly. It insists that life makes sense, that there is an underlying logic.” Newspapers, magazines and procedurals are the last forms hanging on to tidy endings. The rest of us are just, like, living here.

The Heat Is Ruining Your Illegal Drugs

Um, who calls marijuana “hash”? Anyway, this heat wave is much worse than we had previously suspected.

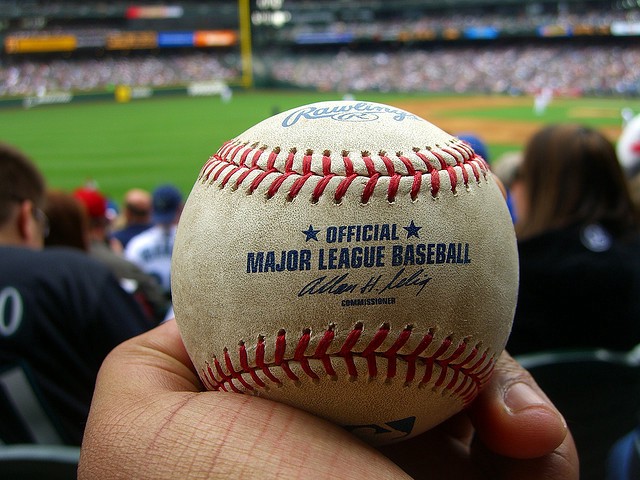

Baseball Fans And The Ball In The Stands

by Herschel Farbman

If the rule is written somewhere, no one has ever read it. Nonetheless, no one disputes it: when a ball goes into the stands at a professional baseball game, it belongs to the fan who gets it. When the ball is the one that was hit to break a record, the fan has won the lottery. The prize can be as high as 3 million dollars (see the ball Mark McGwire hit to break Roger Maris’ single season home run record). The ball that Derek Jeter hit out of the park July 9 for his 3000th hit would have fetched a more modest but still decent sum on the open market — upwards of $200,000 is the estimate of Derek Jeter’s personal memorabilia mule.

So it was certainly notable that Christian Lopez, the cell phone salesman into whose hands the Jeter ball fell, didn’t cash in. Instead, in a touching display of just the kind of generosity big business banks on, he “returned” the ball to a bazillionaire to whom it had never belonged. “Mr. Jeter deserved it,” he said. In exchange, some season tickets and signed bats trickled down, along with many a pat on the head from the press — enough so that no one could say that goodness doesn’t pay, but not what the ball is actually worth. Jay-Z, who was in attendance, just shook his head: “He’s a better man than me.”

The Jeter/Lopez story has been widely covered, but it has been overshadowed — or at least darkly shadowed — by another ball-in-the-stands story: two days before Jeter got his 3000th hit, firefighter Shannon Stone fell to his death at a Texas Rangers game trying to catch a ball tossed to him by Josh Hamilton. Of course, this was all, as Hamilton’s teammate Michael Young was eager to insist, “just an accident.” That it was not, however, an accident of the completely random kind was confirmed four days later, at the MLB All-Star Home Run Derby in Phoenix, when Keith Carmickle, who had already caught three balls, almost fell from the right-center field stands trying to catch a Prince Fielder bomb (Carmickle’s brother and a friend managed to grab a limb apiece as he tumbled over the railing). Such accidents are, as Cardinals right fielder Lance Berkman said of the standard practice of tossing balls into the stands — in response to a question about whether the practice should be eliminated after the Hamilton/Stone disaster — “part of the game.”

Part of the game of baseball, that is, in which the stands play a special role. In no other American sport does the flight of a ball “out of the park,” into the stands, ever count as a point (it does count in cricket, the least American of sports). Indeed, many baseball fans bring a glove to the game, in hopes of getting a chance to make a play. Of course, most fan plays come on foul balls, as home runs are relatively few. But, though the crowd may groan — or yawn — there’s a distant echo of the home run in every foul ball hit into the stands. It’s still a ball over the wall.

The wall that separates the crowd from the field — the inner wall of the double enclosure of the field — is the most important feature of any baseball stadium. No one thinks too much about what that wall looks like at a football game, as it comes into play only after the play is dead (when a player jumps into the crowd to celebrate a touchdown, for example). But thinking of his or her favorite stadium, the baseball fan thinks of that inner wall, and — with iconic fields like Fenway Park in mind — baseball stadium architects look hard for an edge in its design. It’s the outfield sections of the wall, over which home runs travel, that matter most, but the wall is a continuum, broken only when the bullpen door opens to let a relief pitcher enter the game. The outfield sections communicate to the whole a charge that can be felt whenever the wall is crossed — in the little frisson that comes even when a weak foul ball flares into the grandstand, or when a friendly player tosses the ball into the first row.

The thrill would still be there if the fan who makes a play at a pro baseball game didn’t get to keep the ball, but it wouldn’t be the same. Possession confirms the magic of the passage of the ball over the wall. It isn’t quite like this anywhere else: send a ball into your neighbor’s yard, and it remains yours, even if your neighbor is Osama bin Laden (in giving neighborhood kids money for the balls they kicked into his compound, bin Laden recognized the spirit of this law, even as he violated the letter), but send a ball over the wall at a pro baseball game and it belongs to the crowd. Such a transference of ownership happens in hockey, too, when a puck goes over the glass, but the investments in that puck are not the same — the most a hockey team can get for sending the puck into the stands is a delay of game penalty. It can sometimes happen at a football game, when a player gives a fan a ball, but it’s more the exception than the rule there, and the generous player has to pay a fine to the league for making the gift. It never happens at a basketball game.

The magic of the relationship between the baseball field and its beyond is such as to invite the grandest mythical and metaphorical projections. For the orthodox myth of the field of dreams, see pretty much anything written about baseball by A. Bartlett Giamatti, scholar of pastoral, former commissioner, and ideologist-in-chief of the game (or just see the Kevin Costner movie). Meanwhile, the literature of baseball heresy still awaits its great text. Catching sure-handedly all that is essentially urban about the game, Don DeLillo’s Underworld, which tracks the destiny of a baseball hit into the stands, is certainly a big time, big league text, but even the sharp twists it gives to the corndog “taste of Eden” orthodoxy don’t shake the work all the way free of it.

In “The Triumph of Death,” the bravura opening section of Underworld, a puking Jackie Gleason embodies convincingly an unsentimental point of view, but the smoke thrown up by the whole scene is certainly in DeLillo’s own eyes as he watches Cotter Martin, a character he has created to fill a gap in the historical record, collect Bobby Thomson’s iconic home run ball — the projectile in question in the “shot heard round the world.” According to DeLillo’s grand, historical scheme, this “shot” is really two: an early Soviet test of a nuclear bomb echoes it. J. Edgar Hoover, who’s at the game along with Gleason and Frank Sinatra, receives news of the test just as Ralph Branca, whose high inside fastball Thomson will smash, gets up in the Dodger bullpen. Ironic though it is, this doubling of Thomson’s shot amplifies it, resulting in a very impressive bang — the sound is that of the Cold War beginning and the preceding age coming to an end. It does not produce any thinning of the smoke that hovers over the classic ballgame. The Cold War light that DeLillo summons to the game is supposed to be chilling, but DeLillo’s irony is a bit too good. In the end, it only reheats the standard myth, in which a baseball is a little fragment of a world before a fall.

If a baseball were really that, though, fans would not care about the game in the way they actually do. This is hardball, after all: what keeps the fan watching is sheer anxiety over the volatility of the unscripted event itself. The fan obsessively studies statistics and assesses probabilities — and consumes and traffics in all the myths — because he or she lives every day in awful (and exquisite) uncertainty about how the next game (every little bit of it) will go. MLB is absolutely right to fear more than anything a repetition of the Black Sox scandal of 1919, in which games were fixed (though Pete Rose’s lifetime suspension from the game for gambling on it may be a little harsh), as such a disaster would affect precisely what the fan most cares about: not the fairness of the game, exactly, but its unpredictability.

One name for the object of the fan’s most intense interest is “history” (little “h”). Minor though it may be, a game is itself an authentic historical event. No big explosions are necessary. What Shannon Stone was reaching for July 7 was less a token of paradise than a little piece of history — not a piece you could sell for much, if anything, at a memorabilia show (it was only a foul ball, picked up and tossed into the stands by the left fielder, not a significant hit), but a piece of history nonetheless. To call such an object a fetish (and “piece of history” a cliché) wouldn’t be entirely false. But while it was suspended in the zone between Hamilton and Stone, between field and crowd, where all the energies of big time baseball gather, that ball was an indeterminate thing, carrying all the surprise of the actual event.

The hot, highly fetishized commodity the fan in the stands walks away with when he walks away with a more obviously “historic” ball forms itself around this spinning, hard core. That doesn’t mean that Christian Lopez was not silly to refuse to treat the record-breaking ball he caught as a commodity. It only means going for the ball was not, in the first place, a question of exchange and all the calculations that that entails. The ball was there, up for grabs. Like Stone, Christian Lopez just went for it.

The locus classicus of this primal and utterly ordinary response to the baseball event, in all its raw volatility, is the infamous Steve Bartman incident. Thinking of Stone and Lopez (and Carmickle), I can’t help but flash on it. On October 14, 2003, Bartman, a Cubs diehard seated by the rail along the left field line, interfered with a foul ball that Moisés Alou might have caught for the final out of what instead became a disastrous inning for the Chicago Cubs in game 6 of the NLCS. The Cubs lost the game, from which Bartman had to be escorted by a small army of security guards, and went on to lose the series. Bartman has been reviled in Chicago ever since, and lives more or less in hiding. But the ball was right there, in that wild border zone where it was no more Alou’s than Bartman’s. Alou reached for it. Bartman reached, too.

Bartman didn’t make the catch. The ball bounced away into the stands, and someone else walked away with the six figures that Grant DePorter, managing partner of Harry Caray’s Restaurant, paid for it. On February 26, 2004, with great fanfare, the ball was exploded at the Chicago restaurant, which would have seemed to have been the end of the story, except that a year later, the remains of the ball were soaked in beer and boiled to generate steam, which was captured and used in the preparation of a pasta sauce. And so, through a process of sacrifice and communion, the ball was consecrated entirely to the hot air of baseball’s big myth.

Such a rite was inevitable; the raw event had been unbearable. But I agree with the writer of this 2004 article: it would have been better had the ball somehow ended up with Bartman. Were there a baseball god, the story would have ended like this: a Christian Lopez figure would have miraculously materialized in Chicago in the winter of 2003–4 — but upside down, cruel, with pockets full of money — to buy up the cursed ball and “return” it, with all the apologies under the sun, to Bartman, who did everything and nothing to earn it.

Herschel Farbman teaches English and French at UC,Irvine.

Photo by permanently scatterbrained.

Republicans: Barack Obama Will Still Be Running Things Down Here After Apocalypse

A poll shows that only 19% of Republican primary voters believe that Barack Obama would be taken up to Heaven in the event of the Rapture. More than half see Sarah Palin flying up there, or whatever it is happens.

Rebecca Black's Moment

“Rebecca Black borrows from one of hip-hop’s more powerful narrative-engines, the presupposition that everyone is against you:

Weren’t you the one who said that I would be nothing?

Well I’m about to prove you wrong.

I’m not the only one who believes in something.

Which works, if you grew up as a musical prodigy in the Marcy Projects. But Ms. Black didn’t — she is the daughter of Orange County veterinarians whose spayedings and neuterings paid for the “Friday” video — and so she has a problem. The grand cause separating her from the nihilism of the day is in fact merely her own dank puddle of that very nihilism: an unwavering belief in the cosmic justness of her own celebrity despite any basis for it — the triumph of want over talent.”

— Rebecca Black expert Dana Vachon takes a look at her new song and tells us What It All Means.

Tired People Will Seek Vengeance For Terrible Things That Weren't Your Fault

“A new study shows that when people, in this case college students, are sleepy they are more likely to think about how events could have turned out differently and ponder how situations could have been better. Depending on the outcome, they may blame others and even seek revenge.”

A Q&A With Jon Langford Of The Mekons

A Q&A With Jon Langford Of The Mekons

by D.E. Rasso

It’s likely that you either love the Mekons, or you haven’t heard of them at all. Formed as a punk band in Leeds in 1977, the sprawling lineup has remained more or less the same since the mid-’80s. Their sound spans multiple genres, among them American rock and roll and roots music. (They are, in fact, credited with producing the first alt-country album.) If you go to a Mekons show, expect to see some incredibly ardent fans, every music critic in town, and an energetic performance from all on stage.

I had the opportunity to interview Mekons cofounder and guitarist/vocalist Jon Langford while he was on a family vacation in the hinterlands of Michigan. We discussed the history and evolution of the band, the sometimes frustrating process of recording an album, touring, meeting one’s heroes, and the new Mekons album, Ancient and Modern, due out in September.

D.E. Rasso: Is it true that Lester Bangs said that you were better than the Beatles or is that apocryphal?

Jon Langford: He did say that, he did say that. I’m sure it was partially tongue in cheek. Who knows, he said a lot of things.

And Jonathan Franzen gave you quite a nice blurb [for your new album].

Jonathan Franzen is a very nice man. I like his books; they’re very good. He’s been very supportive.

We’re very flattered by a lot of the people who say that they like what we do. But the whole thing about saying there was something “pure” about what the Mekons have done, this whole “authentic” thing, there is a thread that goes back to what our initial kind of manifesto was in 1977. And what the kind of groundswell of feeling was at that time about what a band should and shouldn’t be, you know.

And it was a collective thing that was going off all across the country. It wasn’t something we were just like inventing ourselves. There were just a lot of people who were just sick of it, of how boring the music industry was. I mean, God knows it’s even more boring now…

Well, I was going to ask, do you think there’s even a similar movement in music today?

I can’t say. I’m an old fart now. I really am, a 50-year-old guy, so I fucking haven’t got a clue what kids are doing. I don’t know if it feels the same to them. I just know it was all-consuming and exciting and amazing and the possibilities seemed limitless to me when Mekons formed. And I was 19 years old. And I still hold some of that kind of idealism.

But there was always a lot of humor with the Mekons as well, this kind of barbed edge to it and a kind of Stalinist edge to it… and one week we’d be trying to write, you know, songs to change the world and it’s like socialist anthems and then the next week it was like, “This is a lot of shit.” The thing about the Mekons is we were always very aware of what we didn’t want to do. And as things came up we could have a big list and scratch off all the things we didn’t want to do. And our manifesto was a list of things we didn’t want to do. We never really did say what we did want to do.

What were some of the things on the manifesto?

We will only be a support band. We will never have our photographs taken. We will not make a record. We will not have our names printed, or an address. It all came crashing down. Reality evolved. But the important things were the things we didn’t write down: that we thought a band didn’t have to exist within the structure and rules of the music industry. A band could be whatever you wanted it to be.

That’s what [the Mekons have] turned into: this collective of people who just choose to get together every now and then, and do some things for their own amusement. No pandering. I don’t think we’ve been at a point in our career when we thought, “Let’s do something like that, because that was successful.” It was a real revulsion against that. It was like we tried to shoot ourselves in the foot at every possible point… when things started going quite well with respect to the business [aspect of the band], we would deliberately dismantle that which was working.

What if one of the members of the band were to say, “You know what? I don’t have time to do this anymore,” or, “I think I need to spend some time working on something else,” what would happen?

Well, people have and people do. You know?

But you guys have had a lot of the same lineup for a long time.

We’ll usually just say, “Well, how much time do you fucking need?” On these tours, we only take up about a month of anyone’s year. I don’t think anyone’s really complaining about the workload.

I think there’s this gravity, as well, that pulls us back together. If we haven’t seen each other for a while, it feels odd. It’s a very old friendship between people in the band.

It was like we tried to shoot ourselves in the foot at every possible point… when things started going quite well with respect to the business [aspect of the band], we would deliberately dismantle that which was working.

Is there any sort of Mekons manifesto in 2011?

Not that you’d write down. But I think there’s a cloud of mass delusion that this is actually worth doing. [laughs]

I think sometimes, a lot of times in the Mekons’ career, the motivation, more than anything else, seemed to be like a big fuck-off to the world: “I will not be ground down into dust.”

Clearly, the longevity of the band must have something to do with that.

Yeah, I think it’s a sort of persistence. It hasn’t been financially rewarding for anyone.

It’s been a couple of years since the last Mekons album. What was the catalyst for Ancient & Modern?

We did Natural in 2007 and I think pretty much immediately after that we started trying to record another album, but we’re very spread out across the world and the older people get the more commitments they have outside of the band. It’s not the be-all and end-all of our lives.

You recorded it in the UK?

It was recorded kinda all over. Basically, Tom [Greenhalgh, Mekons member and cofounder] has a job and four kids, and he lives in a thatched cottage in the countryside in the southwest of England, and we were trying to work out a way of recording somewhere while we were on our tour, so it wouldn’t be too detrimental for him, so we ended up renting a house and bringing a mobile studio in. Rico [Bell, Mekons member]’s son Walter came and recorded — he works with Lu [Edmonds] in Public Image Limited, he does their sound — so he basically set the whole thing up in the house, which was quite odd. It was obviously some sort of sex-obsessed bachelor’s pad, kind of arty but lots of paintings of nude women on the walls and stuff.

How did the female members of the band feel about that?

Thought it was ridiculous [laughs]. It was kind of creepy. It was weird… But it was also within walking distance from Tom’s house. So that was kind of useful, and he could go to work in the daytime and come over in the evenings and do some recording late at night, so it was kind of a 24-hour recording thing going on, with Sally [Timms, Mekons member] coming down the stairs in the middle of the night and telling us to shut up because she was sleeping.

So at some point in the distant past did you imagine that being a musician was going to be a full-time job?

No, never really. It has become one at times and then that’s when it’s been the worst experience, to be quite honest.

Yet you guys put a lot of energy into touring and into your live shows. Do you genuinely enjoy being up on stage?

I’d have to say we do. I think people enjoy it, but it has to be the right circumstances. We’ve had horrible times on stage, just even recently.

Really?

[Sometimes] you end up doing a gig with couple of vital people missing because they’ve got other things booked, and then it’s really difficult.

But I’ve seen the Mekons and the Waco Brothers dozens of times, probably, over the past 20 years or so. I have to say that the energy has always been really fantastic, both onstage, and I feel like your fans have a particularly special energy. My perspective is from being in New York, where audiences, I think, are blasé in general; yet, the audiences at Mekons shows, I think, are pretty energetic and excited to be there.

There’s different sorts of energy, as well. I mean, we played The Bell House [in Brooklyn] a couple of years ago. We had a great night. Then the next night, we played a club in Manhattan, and we played a lot later, and it was just a very different atmosphere. It was very strange. Suddenly, it was like we went from Woodstock to Altamont.

The Bell House is a great place to see shows.

I performed there with the Waco Brothers, with Skull Orchard, and with the Mekons, and had a great time every time. I really like that room. The people there are really nice; that helps. When a club’s just starting out, it seems like they go the extra mile, and they’re still enthusiastic. There’s clubs in New York I’ve played at, where I’ve actually said to the people, “You should stop doing this. You’re obviously not having a very good time.”

What cities, or particular locations, have you liked performing in the most?

We’ve enjoyed playing Zurich lately. We’ve done some great shows in Zurich the last year. We went back again in June and did two shows. It has been really surprising some people, to go somewhere and see people be really interested.

Do the Swiss just get you better than Americans do?

It was just that we hadn’t been to Switzerland for about eight years, and it was like this grand homecoming. I think absence makes the heart grow fonder. We should take eight-year breaks from all of our regular markets.

Yeah. Maybe pretend to break up and then get back together, and then…

That has been our biggest mistake, never breaking up.

I think the repartee that you guys have onstage with each other, if it’s real —

What do you mean? We wouldn’t be able to say all those things to each other if it wasn’t real. Mekons has been real, I can tell you.

Yes, I know, um [frantic apologetic mumblings]… What I meant was to emphasize that this is part of the reason why I was so enthusiastic about being able to talk to you. Because of the fact that it’s one of those things where you often don’t want to end up meeting people that you idolize, because you’re worried that they’re going to end up being disappointing. But I hoped that wouldn’t be the case.

You know what? That’s 50% true. In my experience, I have heroes, and some I’ve met and been awfully disappointed, and just thought they were horrible. Then others I’ve met, and they’ve been amazing.

You met Johnny Cash, right? A number of years ago.

Yes. He was not a disappointment and not what I imagined. Nothing like the fuckin’ I Walk the Line myth, the Hollywood crap. Nothing like that at all. Very funny, humble, gentle guy.

Who else have you met that you’ve really enjoyed meeting?

Well, I’ve got some people I really like whom I’ve actually had the pleasure of working with. I worked with Johnny Cash a bit on that record we made in the ’80s. I made a record with Kevin Coyne, who’s a singer/songwriter from England, who I was enamored with from a young age. A notoriously difficult guy, someone that I was told would be horrible to meet. I was scared. When I met him, he was great. We got on, we had some fun, and made an album together; had a really nice time.

And also, John Cale. Lovely. I met him. Everyone warned me that that was going to be a nightmare, so I steered clear.

Perhaps it’s just that you just bring out the best in everyone else.

Do you think so? I try. [Birds chirping in the background]

You even bring out the birds.

Yeah, I’m standing in a kind of nature preserve-y area of some sort.

There has always been a hatred in the Mekons of self-righteousness and purity, which are [characterizations] that people have cast upon us. We’re just a group of people who choose to work together.

So the new album.

Yes. We mixed it with Ian Caple, who mixed [Mekons albums] Rock ’n’ Roll and Honky-Tonkin’.

It’s funny, I was thinking “Space In Your Face,” off the new album, has a rich, full sound, sort of similar to Rock ’n’ Roll.

Working with Ian, he really understands where we were coming from. It started off as just a really light little tune, played on acoustic guitars, in a cottage somewhere in Devon. Then we took it back to Chicago and just kept amping it up, and amping it up. … But [often, the contemporary recording process can be] a terrible, terrible process that we’ve come up with. Really idiotic, expensive, and wasteful; but the end result I’m satisfied with. I think.

Wait — is recording an album worse than touring, than performing live?

I think it’s more stressful. There are moments that I really enjoy that feeling of just being in the studio, when you’re writing and ideas are really flowing, and it’s very immediate. But there are also periods of waiting around, and fracturing things, and I don’t enjoy it that much.

But we were pretty much on the same page with this record. It was a kind of pragmatism [where we accepted that] not everyone’s going to be there all the time. Usually with the Mekons, everyone has to be in the room when everything happens; with this, people could do their bits and send them in. We tried to utilize the miracle of the Internet. But it’s not a labor-saving device; really, it just makes for more lack of sleep.

But when we came to mix the stuff, we were actually recording and singing bits on it while we were mixing it; and radically editing the songs, losing big chunks of things, and adding other things. I don’t know, it just never stopped evolving. I like the idea of making an album where you go for a week, and then end up with a finished album. This was like, two years of thinking about something.

So has technology made it more difficult rather than making it easier?

It’s 50/50, you know. I think if you use it creatively, it’s fantastic. There are amazing tools but it can also become a trap, you know. You can just get sucked into it, and then there’s no reason to ever finish anything. There were a lot of reasons for not being able to finish this album quickly.

A lot of it is just the logistics of — oh, a beautiful red cardinal just flew by, looked like a bloody great parrot, fantastic — so yeah, that’s kind of the rules of the Mekons: There are no rules…. why shouldn’t we spend two and a half years making an album from different points in the world, you know? There’s no reason not to. It’s like we mixed it and left it for a little while and didn’t listen to it. Before we sequenced it and Lu mastered it in London….

And mastering is really important but it’s a process I really hate attending. I don’t understand the magic that goes on there. But then getting it back with all the tracks in order, all kind of tweaked so they were all the same level and suddenly it was like, Wow, now it’s an album. Now it’s an album I can just sit and listen to. I have little favorite bits and I’m not constantly remixing it in my head. I hope it’s like that for everyone else as well.

What are you envisioning for the next album?

Oh, to go into a room and emerge a week later with a finished album. Just to record a lot of stuff and then edit it down and decide on something else. I just want something a bit more immediate. This was actually anything but immediate and it found it took up a lot more of my brain than I wanted it to for a long time… It’s creative and frustrating at the same time.

This new record is on your own label, Sin Records, that you’ve revived, right?

Yeah, it’s the label we worked with, the label we created when we had a manufacturing and distribution deal with Red Rhino in England. It lasted up to the point where we did three or four records with it, then we went to Cooking Vinyl…[eventually we ended up with] A&M; in the States, which was this strange slide into professional-ness, which none of us were really that interested in.

We had a very safe harbor for 15 years with Touch and Go, who picked us up and said, “You’re kind of interesting. Let’s see if we can work together.” It was just this seamless, easy, great relationship for 15 years, with people we really trusted, and without the danger of somebody just trying to scam us. But then they stopped putting records out. [Reviving Sin Records] seemed an obvious thing to do, to try and find someone who would do a manufacturing and distribution thing, but to have our own label again.

Bloodshot Records are close at hand in Chicago and I had worked with them a lot. They didn’t need a lot of explaining about what the Mekons were about. We thought if we went with another label, a proper label, it would just end in tears, because they wouldn’t understand what the band does. It’s pretty hard to explain the way we work, in our way, our level of ambition, et cetera, et cetera.

What is your level of ambition?

Zero. So, with [Bloodshot] knowing so much about the band, we thought that relaunching the Sin label might be a cool thing.

Then do you prefer the DIY approach to music?

During the development of punk rock it was just that, just putting aside the notion of dealing with the proper music business. I mean, we did deal with the proper music business at various times…

With A&M;?

A&M;, and Virgin before them. They weren’t really happy experiences, to be quite honest, although in both those situations, I think we made really good records. But we got kicked off those labels for making the records we wanted to make and not “polishing the turd,” as we would call it.

It was interesting to be on major labels, but also completely soul-destroying at the same time. I think we learned a lot. Creatively, it wasn’t necessarily that bad; but personally and financially, it was pretty depressing. I never really wanted to make the band a career. We bent over backwards to try and work out what was going on, and be good employees… until we gave up.

When you started out in Leeds, you were surrounded by this punk ethos, and a lot of bands that are also quite well known. Do you feel like now, 30-plus years later, you’re still subscribing to that same ethos? Do you feel like you have been able make music without making too many compromises?

Oh, I think we’ve made loads of compromises, willing and unwilling. But we’ve experimented, and asked ourselves, “Why are we doing this exactly? What if we do this?” I think that’s the case with the major labels, was why we were being pure. There has always been a hatred in the Mekons of self-righteousness and purity, which are [characterizations] that people have cast upon us. We’re just a group of people who choose to work together.

Wait, so are you saying that you don’t like the idea that you’re characterized as being authentic?

No, not at all, I think it’s a load of bullshit. I’m no more pure than, I don’t know, custard.

There is a certain amount of veneration that the Mekons get from fans and from critics alike.

You know, that’s not the reason why we’re in it, you know. We’re quite uncomfortable with that.

So, with Ancient & Modern, what was the idea behind it?

The original working title was A Hundred Years Ago. The 1911–2011 thing was a very conscious decision, to talk about the last hundred years, and what was actually going on at that point in history just before the First World War. There’s definitely a theme, you know, even if it’s loose and tangential.

It’s a concept album?

It’s a concept album, yes. It does have a concept. … I think that most of our records have a concept behind them, so…

Is it actually going to be on vinyl as well as CD?

Yeah.

But not 78.

[Laughs.] Actually, it’s all wax cylinder.

That would have been awesome, actually.

Yeah, that would have been good. We would have sold even fewer records than before, and that’s always appealing to us.

Does each of the songs have a particular connection to an event that occurred a hundred years ago?

Definitely. “Space In Your Face” actually talks about the bombing of the LA Times. It was a time of domestic terrorism, huge corruption, and witch trials… so there are all of these similarities [to today]. It’s almost like that period leading up to the First World War was like the end of human history as it had been. And what we’ve lived through, from the 20th century ’til today — it’s just the modern world, you know, and all of its glory and destruction.

Now there’s a train going past. Bird noises have been interrupted by train noises now. I’m having a very American moment.

D.E. Rasso is a writer and blogger who has spoken inexpertly on the topics of music criticism, the future of publishing, Internet impostors and weird things from dollar stores.

This conversation took place by phone and has been condensed.

Murdoch Hearing Suspended Due to Attack

Cameras cut off immediately at the Murdoch hearing as people in the room yelled — from what we could see, it looks like someone charged Rupert Murdoch from the audience. More as everyone figures out what the heck just happened. According to Josh Robin, who just rewound the tape: “Just looked at feed again — Rupert Murdoch was approached and seemingly attacked but does not appear to have been knocked down.” THIS MAY HAVE BEEN A PIE ATTACK. Also: “Murdoch attacker taken out of the room in hand-cuffs,” says Sky News. Apparently Wendi Deng got a swing in at the person? “Rupert Murdoch was pelted with a white substance during testimony — police have man in custody,” says Times UK. And now with slo-mo video, featuring Wendi Deng lunging into action. A+++.

And here’s who’s taking credit for it.

It is a far better thing that I do now than I have ever done before #splatless than a minute ago via Twitter for iPhone

Jonnie Marbles

JonnieMarbles

Protestor said “You’re a greedy billionaire” before hitting Murdoch really hard on the head. Looked like serious assaultTue Jul 19 16:03:39 via Twitter for Android

Paul Waugh

paulwaugh

And the hearing has resumed.