The Oakland Police Department's War on Citizens

Oakland’s police chief Anthony Batts resigned a couple weeks ago, because, when he wasn’t busy applying for other jobs, he was busy trying to turn Oakland into a police state, and that mean old City Council wouldn’t let him. His approach to policing was that crime would stop if you instituted a curfew for young people and if you could immediately arrest anyone found “loitering” anywhere in Oakland. Also, a decade on, he and his predecessors still couldn’t enforce court-ordered changes to the police department arising from the sensational “Oakland Riders” trials, which also ended in zero convictions of police but a $10 million settlement to 119 different plaintiffs. The court supervision agreement includes not very outlandish things like “Improved reporting and investigation of use of force by officers.” Apparently that is not something that can happen in ten years. Longtime department member Howard Jordan took over as chief — for the second time, as retention of chiefs has become a problem for what is an extraordinarily troubled police department. And then, last night happened.

The routing of Occupy Oakland began early in the morning yesterday and continued into the night, with protesters trying to retake Frank Ogawa Plaza (or, as Occupy Oakland quite properly calls it, Oscar Grant Plaza).

Later today, Occupy Oakland will retake the plaza, despite promised further violent tactics by the Oakland Police Department, including beanbag bullets, teargas and possibly even a sound cannon. This unbelievably strong-armed approach is both completely inappropriate and completely in keeping with the history of policing strategies of Oakland. Also par for the course: lying about what happened afterward.

Mayor Jean Quan, whose statement Tuesday morning was “We want to thank the police, fire, public works and other employees who worked over the last week to peacefully close the encampment,” was in D.C. yesterday, lobbying for money for the port of Oakland, while the encampment was being not at all peacefully closed. Meanwhile, reversals happened in Atlanta and Baltimore, where Occupy encampments were raided by police.

Since the newspapers tend to show Oakland’s riot cops petting kittens (LITERALLY, at the Washington Post), consider keeping an eye on Oakland North, Bay Citizen and Awl pal Susie Cagle.

Photo by Occupy Oakland.

A Conversation With Chris Perkel, Editor of 'Pearl Jam Twenty'

It was never easy being a Pearl Jam fan. The explosion of hype and overexposure that came with Ten and Vs. fueled an instant mainstream backlash by the “cool indie kids.” If you were going to listen to grunge, Nirvana was the band you were supposed to like. The experimental, less radio-friendly Vitalogy and No Code — as well as the annoying rise of Eddie Vedder sound-alikes — slashed the fan base even further. In terms of popularity then, they occupy a strange, contradictory place in music: They’ve been one of the biggest bands in the world for two decades but comparatively little is known about them. Which is why the Cameron Crowe-directed love letter Pearl Jam Twenty (out today on DVD and Blu-ray) is such an important document. A fan himself, Crowe was given access to the band’s entire video vault, footage that documentary film editor Chris Perkel had to comb through, culling a two-hour retrospective from over a thousand hours of raw material.

Perkel, who’s in Panama shooting a documentary about international census workers, took time away from watching the GOP debates (“high comedy,” he says) in order to talk about the process.”

Rick Paulas: How were you approached for the job?

Chris Perkel: I’ve been cutting docs for seven years and worked for a director named Morgan Neville who does a lot of music documentaries. He was approached by Cameron Crowe about the Pearl Jam doc a while ago; Cameron hadn’t really done any documentary work, so Morgan was brought on as a producer. Immediately, I was trying to find an avenue in because, you know, I’m in my mid-30s and Pearl Jam was a band I had a connection to as a teenager. So they gave me the chance to cut a little teaser and that ended up basically being the trailer they use now. They got that I was a fan and I had some understanding of what they were trying to do. So they gave me the opportunity to edit a music video for “The Fixer,” and then gave me the job cutting the feature.

How did you go about cutting the movie?

It’s a weird film. Usually you do the interviews first and build your skeleton on those. But here they didn’t do the interviews until last. So the first thing we did was find performances or clips we thought were particularly cool or interesting or rare. Sometimes it’s pretty subjective, so you hope you have similar taste to what most fans would like.

Did Cameron Crowe tell you exactly how each section of the narrative should go?

Early, Cameron would come in intermittently. We would have conversations about the tone and vibe he was going for, and we were trying to suss out from him what he’s trying to do, but we had a lot of independence early on. You can kind of tell when you’re on the same page and when you’re not, if you cut something and got the vibe he wasn’t responding to it. But for the most part we had a good sense of what it was he was trying to do. He was very articulate about the goal of trying to make this as if fans had raided their vaults, like you were hanging with the band. Cameron works through tone more than any other filmmaker I’ve worked with, so we’re always trying to make sure the stuff captured a particular tone or feel. If you did that, he was generally pretty happy.

Were there any worries that the first half of Pearl Jam’s career would be over-represented in the movie?

There was some talk about it, because it’s hard to avoid. Obviously, the first few years of their career has a lot more drama. I still don’t think we did as good a job as I would’ve liked in dramatizing the second half, but we did the best we could. And, frankly, it’s the stuff people respond to more. You know, those first two albums were so huge, you had to emphasize them to a certain degree. Plus, we just had less material to work with in the latter part of their career. It just worked out that we ended up having the most amount of material on the period of the band that was most interesting anyway.

Did you have a constant incoming supply of footage to go through?

It was evolving, but we had a lot of it up front. The other editor, Kevin [Klauber], had spent a year going through material, syncing footage, breaking down old performances, that kind of stuff. But stuff was still coming in as we were going. Then, you reach a point where you need certain things so you have to hunt for them in order to fill out the story. One of the last things we got was the footage of Eddie Vedder and Kurt Cobain slow-dancing at the VMAs in 1992. We knew it was out there, but couldn’t get it for months and months.

Were there any pieces you stumbled on that you were shocked you had?

Them writing “Daughter” on the bus. Instantly, we were like, that’s great. There’s some really old footage of Stone and Jeff and Andy Wood from Mother Love Bone that one of their friends, Josh Taft, was just shooting while they were hanging out at a Cult show. And the second show ever. The fact that it was even filmed was ridiculous. It just so happens that Alice in Chains, who they were opening for, were shooting a music video and decided to roll on Pearl Jam as well. They were Mookie Blaylock at the time. There’s some footage of them hanging out with Alice in Chains that’s cool. And the footage from Roskilde, the festival where the kids died, the fact there was footage where you can see the band’s reaction on the Jumbotron was pretty riveting.

Is there anything you wished would have stayed in?

When they shot the “Even Flow” video they had four cameras going and did a whole set that night. They did “Once,” “Why Go?,” “Porch,” and “Baba O’Riley.” In the film, we cut three different “Baba O’Riley” performances together, starting with them rehearsing backstage at Lollapalooza, and then we go to a live performance that’s modern, and then we used the tail end of that show. But there’s amazing footage of them playing these songs in 16 millimeter film that just didn’t make the cut. Oh, and there’s footage from this radio show, “Self-Polluted Radio,” in the mid-90s. We had a great version of “Corduroy” which is a song that everyone loves that didn’t make the film at all. It’s them in this little rehearsal space, very intimate, but it just didn’t have a story to go along with it. That was kind of depressing. There was — I think this is in the DVD extras — a cool little piece I cut of Matt Cameron walking us through how they took a demo he brought in called “Need to Know” and turned it into “The Fixer.” You see the whole evolution of the song. There really isn’t any studio work in the film, because it just didn’t fit.

When dealing with a music documentary, how much does the sound quality of the footage affect what you keep and what you cut?

It does to a degree. The sound quality for their second show ever, we knew we were just taking whatever they had. The value of that footage wasn’t in the quality, it was in the rarity. And from 1995 on, they’ve archived everything impeccably. We worked with their sound guy, John Burton, and mix them a little. But it was really only the early stuff that we had to worry. If the footage was rare and cool, it really didn’t matter.

Did the band have a lot of input in the film?

Honestly, not on anything big. The film was basically a collaboration between Cameron and their manager, at least the genesis of the film was, so people assume this was a more sanitized version of the band. But when we went to Seattle to show them the cut for the first time, it was really tense and nerve-wracking because we had no idea how they were going to react. They’re notoriously private. There’s some dicey stuff in there. Aside from the Roskilde thing, there’s them talking about the change in dynamics from Stone losing power and Ed taking power. The drummers. There’s some tricky stuff. They had notes, usually stuff they found embarrassing, a line that Ed didn’t like from old footage that made him feel goofy. They tried to get rid of a couple things, but we ended up pushing back. Nothing of substance ended up changing. Basically, this film would have never happened if it wasn’t for their relationship with Cameron. They’ve known him since the band’s inception, and they trust him. They really let him make the movie he wanted to make knowing he wasn’t going to do a hatchet job.

It’s definitely a movie by the fans for the fans.

Totally. It’s been interesting seeing the critical response, because I feel the movie accomplishes what it set out to be. There are some critics that don’t believe films should exist if they’re not being more critical. But for the most part I think it’s been well received. It is what it is. People really like it because it’s a movie that clearly gets what people like about the band.

Just the fact that they’ve been around for 20 years shows you’re not going to have insane controversies you dig up.

Right. I really don’t think there’s more there than we talked about. This is a fairly honest depiction of their story. This is a band that was genuinely uncomfortable with how big they got, and took active tangible measures to make themselves smaller, which is something you just don’t see. You see bands paying lip service to wanting to maintain some credibility or wanting to do it for the music, but usually if people stop shining the spotlight on them they get scared and start waving their arms around saying, “Look at me, look at me!” These guys never did that because their priorities was always about the music and the fans. And they evolved into this crazy live act where they’re as much communal ring leaders as they are band members at this point. Really, how many bands from that era are still around? Not many. And how many are still relevant? There’s only a handful. Either you keep making radio hits like the Red Hot Chili Peppers, or you’re Pearl Jam. That’s about it.

For being as overexposed during their early period, they’re still kind of an under-talked about band.

Totally. When they retracted from the spotlight, they really retracted from the spotlight. They’ve never re-entered mainstream conversation, except for the fans who are as hardcore as they’ve ever been. But they don’t get any mainstream exposure, and they don’t get the indie, KCRW-style exposure that a Radiohead or somebody else would get. They were really genuinely off the radar. Eddie Vedder lives in Hawaii six months of the year, off the grid. And for people who didn’t grow up around them, I feel like they’re undervalued. For the people I know, the people I went to high school with, the band was really a large part of their teenage years in ways that aren’t appreciated by those who weren’t there. Because they haven’t been talked about to the degree that, say, Kurt Cobain was. And they had a greater emotional connection to Pearl Jam than they did to Nirvana.

When it was the Pearl Jam vs. Nirvana debate during the ’90s, was Nirvana more popular because they weren’t as perceived as mainstream? Because Nirvana was playing acoustic shows on MTV. They were pretty mainstream.

Nirvana was clearly more punk, and it gave them more credibility. I think what the critics that dismissed Pearl Jam don’t recognize, they don’t look past the fact that musically they wasn’t as innovative as Nirvana. Clearly, Nirvana was doing something… well, maybe they were just doing what The Pixies were doing. But there was a greater musical break with what was traditionally popular. Pearl Jam was musically like any rock band in the ’70s, more or less. But thematically, Pearl Jam was very different and reactionary. Thematically, they couldn’t have been more different from the hair metal that was out there, even if sonically they weren’t. And I feel like critics dismissed them because of it. They didn’t appreciate how people were responding to the emotional quality of the music. It was so sincere it almost became a joke.

And you have a retroactive thing happening in the late ’90s with people hating them because of bands like Creed.

That’s also true. His voice became so ubiquitous and omnipresent, all of these bad bands that came around, knocking off the Pearl Jam sound, and people resenting them because Creed became so big. You can’t really blame them for that.

It’s why I hated Rage Against the Machine.

Totally. Because of Limp Bizkit. It’s not Rage’s fault that they created this whole genre.

But as a kid, you’re just looking for an excuse to hate something.

And Scott Stapp gives you many, many reasons to hate something.

Related: “Pearl Jam Songs, 1991–1996, In Order.”

Rick Paulas still maintains No Code is their best album, partially because it truly is great and partially because it makes him a bit of a contrarian.

America's Tent Cities

“All over the country, in the last few years, police have moved in on the tent cities of the homeless, one by one, from Seattle to Wooster, Sacramento to Providence, in raids that often leave the former occupants without even their minimal possessions. In Chattanooga, Tennessee, last summer, a charity outreach worker explained the forcible dispersion of a local tent city by saying, ‘The city will not tolerate a tent city. That’s been made very clear to us. The camps have to be out of sight.’”

— “Homelessness is not a side issue unconnected to plutocracy and greed.” Although don’t remind Jersey gov Chris Christie about his plans to help the residents of Camden’s four tent cities. (FOUR.) Meanwhile, Seattle has legalized tent cities when they’re run by religious institutions. The only tent city in America that was even fairly well-resolved was the encampment of convicted sex offenders, who were legislated out of living anywhere else.

"Halloween? Or Williamsburg?"

From the very same Internet that brought you everything else comes Halloween or Williamsburg Dot Tumblr Dot Com.

The Silent Majority Stirs

“Google has decided — without any user consultation — to kill our beloved Google Reader, and force us all to use G+ in its stead. Without any of the functionality that made Reader so useful transferring over to make G+ work for us. In doing so, they are destroying all the features that makes Google Reader so great, and destroying a thriving community of dedicated and loyal followers. We are the demographic that Google needs the most, and we need to let them know what they are losing, and what changes they need to make to this plan to win us back. Join us for this peaceful protest outside Google’s DC Headquarters, and let our voice be heard.”

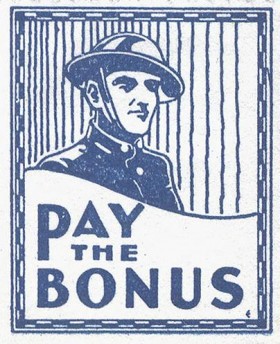

What Does The Bonus Army Tell Us About Occupy Wall Street?

They called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force, or the Bonus Army or Bonus Marchers for short, and in 1932 they set-up semi-permanent encampments in Washington D.C. Nearly 80 years later, people are occupying Wall Street, and many, many other places around the country. And as loud as the shouts of deliberate mass media ignorance were a month ago, the Occupy movement is not all over everything, and it’s as difficult to avoid coverage now as it was to find it then. It seems to be a unique construct, a product of now — nonviolent, persistent and inchoate in the sense of there’s too much to say (rather than not being able to say it). But they’re walking in someone else’s footprints, whether they know it or not.

Comparisons of Occupy Wall Street to the Bonus Army are not entirely new; mentions have been made in the past month (and more recently by Frank Rich in his piece looking at the new Class War), and rightfully so. In fact, efforts to parse Occupy Wall Street by historical comparison are a new cottage industry. Correlations with the Tea Party (both of them) are popular, based purely on the putative populist nature of each, and echoes of the war protests of the ’60s do pop up as well.

No one is suggesting that a wormhole opened up and pulled a historical event straight into modern times, or that, say, a magic shoe was found and worn by an Occupy Wall Street organizer, filling him or her with the channeled knowledge of Eugene Debs manifesting itself in the form of a well-managed listserv. I just recommend that a comparison the Bonus Army is apt, because in 1932, what they did basically was Occupy D.C.

The arrival of the Bonus Army was quite dramatic. They came from all over the country. Some of them just picked up stakes and brought the family with them, figuring there was nothing left to come back to. They made their way, some in groups, some one by one. More fortunate America helped them along: road and bridge tolls were waived, and the travelers weren’t rousted like the everyday forgotten man. When they reached D.C., they set up camps, tents when they could, or shanties cobbled together from tarpaper and scrap wood and whatever they could scrounge.

This is the account given by Evelyn Walsh McLean, wife of the owner of the Washington Post (and owner of the Hope Diamond):

On a day in June, 1932, I saw a dusty automobile truck roll slowly past my house. I saw the unshaven, tired faces of the men who were riding in it standing up. A few were seated at the rear with their legs dangling over the lowered tailboard. On the side of the truck was an expanse of white cloth on which, crudely lettered in black, was a legend, BONUS ARMY.

It’s not exactly the same sense that you get from a Flickr feed of Occupy Wall Street, but it does resonate with the sense of purpose (once you get past the rote Dirty Hippie response) of those willing to spend a month or more on what’s essentially a Manhattan sidewalk.

But considering the variety of opinions considering what might have resembled or inspired the current movement, let’s ask the question: are these historical parallels are useful at all? Is there utility in this, or is it just a chaff thought experiment, noise to the signal?

For perspective on that, I had an email conversation with historian William Hogeland, author of (most recently) Declaration: The Nine Tumultuous Weeks When America Became Independent, May 1-July 4, 1776. At his website, he’s been writing about the history of American economic protest and how it ties in with current circumstance. (His suggested reading list is of particular value.) Also note that Hogeland’s bailiwick is not the Bonus Army or the Great Depression, but rather the populist movements of the 18th century, when the United States was a concept and not yet a practice.

I asked him straight up if it’s fair to talk about Occupy Wall Street in the context of its antecedents. He (naturally) finds them entirely valid. “People generally don’t seem to know much about the long — very long — tradition of American protest specifically over economic issues and high finance’s corrupting relationship to government,” he said. “The tradition is right under our noses, but until Occupy Wall Street, we’ve often thought of protests as occurring over specific, anomalous wrongs that need to be corrected, or over broad ideology, but not over the way money, finance, investment, and taxation pervasively work in our society.”

This is one way that the Bonus Army of 1932 is entirely unlike Occupy Wall Street: the Bonus Army had a very specific redress they were seeking. They were veterans of World War I. After they returned to the US, an act was passed in 1924 that gave the vets a bonus in the form of a fee per day of service, but it stipulated that the bonus would be held and bear interest for 20 years. By 1932, when the Bonus Army converged on D.C., some of the participating veterans (of a truly horrific war, btw) had been out of work for years. What they wanted was a bill to be passed by Congress and signed by President Hoover that would permit the vets to access this bonus before the 20-year maturation date. And by early summer of 1932, there were roughly 40,000 of them in D.C., waiting.

Occupy Wall Street is somewhat more diffuse in its goals, and more in line with the 18th century events that Hogeland writes about. Though, to be fair, Occupy Wall Street has been very, very vague (and purposefully so) as to what they’re looking for. I asked Hogeland if that was in any way unique, from an historical perspective: “The absence of articulated demands on the part of OWS may be unique or at least highly unusual in American economic-related protest. The 19th-century Populists demanded specific, radical legislation to benefit ordinary people. The Whiskey Rebels wanted fair taxation. The Shaysites wanted fair taxation and debt relief. And they said so.”

Maybe it’s spurious to compare the circumstances of the two: then, the occupiers were veterans, crushed by the circumstances of the Great Depression, moved to uproot their lives in hopes of a very real result, and now, a melange of the generally dispossessed, moved by frustration over a financial system suspected to be rigged. There are similarities, so maybe not as spurious as it is too tenuous to avoid refutation.

The two movements shared an analogous backdrop. Just as Occupy Wall Street unfolds in the shadow of the fiscal crisis of 2008 and the Great Recession that followed, the Bonus Army congregated in the full bloom of the Great Depression. Without the downturn, neither protest actually could have happened. There was even a specific federal program that inflamed each: instead of the TARP program that doled out free taxpayer money to financial institutions recently, Hoover had established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, an entity to save the large banks and railroads through government loans, just months before the Bonus Army declared their march. So both the Bonus Army and Occupy Wall Street were set into motion in response to almost deliberately provocative federal policy, and the economic horror show that necessitated it.

And as Occupy Wall Street has current celebrities, the Susan Sarandons and Alec Baldwins, the Kanye Wests and the Jeff Mangums, stopping by, the Bonus Army had one of the more popular military figures of the time, Gen. (Ret.) Smedley Butler, then the most decorated Marine ever, visit and give a pep speech:

Men, I ran for the Senate in Pennsylvania on a bonus ticket. I got the hell beaten out of me. But I haven’t changed my mind a damned bit. I’m here because I’ve been a soldier for thirty-five years and I can’t resist the temptation to be among soldiers. Hang together and stick it out till the gates of Hell freeze over; if you don’t, you’re no damn good. Remember, by God, you didn’t win the war for a select class of a few financiers and high binders. Don’t break any laws and allow people to say bad things about you. If you slip over into lawlessness of any kind you will lose the sympathy of 120 million people in this nation.

Try to imagine that speech given in small bites, repeated in waves throughout an Occupy Wall Street general assembly, and it wouldn’t be out of place at all, would it? (And some not-bad advice to boot.)

And there is one trait that, of the major American protests, is shared only by Occupy Wall Street and the Bonus Army, that of a population, moved by varying degrees of perceived unfairness, to make not just a statement but to erect a semi-permanent edifice, to occupy. Not a march, not a riot, not a long-term picketing effort, but people uprooting themselves and planting themselves in a temporary autonomous zone, in the interest of making a point. Occupy Wall Street has Zuccotti Park, and the Bonus Army set themselves up primarily Anacostia Flats, across the river to the southeast from the Capitol in a bit of land within the skewed cube of the D.C. city limits that would otherwise be Maryland.

To be fair, while they both share occupation as a tactic, Occupy Wall Street is using it to address the ineffability of its goal in a way that did not confront the Bonus Army — not just a squishiniess in targeting, but the conundrum of possible tangible results. Says Hogeland, “Sitting at a white’s-only lunch counter deliberately breaks the precise law you want ended, and it calls the world’s attention to the law’s immorality; arrests dramatically underscore all that. Civil disobedience doesn’t work when there’s no law for protesters to deliberately break in hopes of getting it ended.” Setting up a camp, attracting attention, is a different creature than civil disobedience, and is more like the polite but insistent refusal to not be paid attention to. The Bonus Army was ready to leave once they got their bonuses. It’s as if once Occupy Wall Street stops occupying Wall Street, they will lose cohesion and purpose, as Occupy Wall Street will be ready to leave when, well… I guess we don’t know when they’ll be ready to leave, or what the outcome will be (barring further drum circle controversies). That will be one for waiting.

The historical context of American economic protest is not one easily digested in the course of a brief article on the web. This is Hogeland’s thought on the subject (and why you should consult his work):

We don’t know much about that founding protest tradition of the 1700s, but the famous founders did! They bent all their efforts to squelching it. That’s not a very nice thought, and it raises uncomfortable questions. Everybody from the Tea Party to the liberal/conservative establishment to Occupy all Street wants to claim the spirit of the American Revolution in the form of one or more of the famous founders, but only the modern Wall Street Hamiltonians are on any kind of solid ground with such claims — and they never want to admit (or even know) what Hamilton was doing. So maybe that’s why we don’t want to know too much about the original American protests and riots over economic and finance matters — protests that had a lot to do with getting us here at all. Those protests raise more questions than they answer. And neither establishments nor movements like questions.

This is not a new game being played. Occupy Wall Street is the latest iteration, and what is being “protested” is not something the Department of the Treasury did three years ago, or even something the financial services industry has done in the atmosphere of deregulation initiated by the Reagan administration. This is just continued seismic activity caused by the intrinsically American tectonics of capital. Maybe the game is rigged and the outcome of Occupy Wall Street will be less good than we hope. But let’s look at the Bonus Army, as we know how that went down.

The bill that would have immediately released the bonds to the Bonus Army? It had support, but was ultimately defeated by House Republicans, worried about balancing the budget. The Bonus Army stayed, resisting numerous incentives to decamp. So, on July 28 skirmishes with the local police led to an attack on the Bonus Army by the actual Army. Gen. Douglas MacArthur led a force consisting of infantry (bayonets down), cavalry and six tanks, which razed the shantytowns of the Bonus Army, pushing them into the river as if the Bonus Marchers were the Kaiser’s men fifteen years previous. The camps were torched. Two Marchers were shot and killed. And that was the end of it.

But actually it wasn’t, as the effect of the Bonus Army, the fallout, was a little bit less than immediate. For one, it contributed to the defeat of Herbert Hoover, as the rout of the Bonus Army was terribly received by the American public, and 1932 happened to be an election year. And while obviously other factors contributed to the end of the Hoover administration, the administration that followed was the Roosevelt administration, which effected an unprecedented amount of social reengineering in the form of the New Deal.

In fact, the former Bonus Army benefited greatly from the New Deal, as the opportunities afforded by the various initiatives (the TVA, the WPA and the CCC) employed the scattered forces of the Bonus Army, and employment ended up being more life changing than the early redemption of a service bonus.

So let’s cling to that optimism. It would be awesome if at the end of the Occupation of Wall Street the system was righted, income inequality dispersed, banks not big enough to fail, etc. Not likely, but it would be yell-out-loud awesome. But if the ripples of Occupy Wall Street are only gradual and only turn into actual waves when they crash on shore in a year, or two, or five? It would be a worthy accomplishment.

Brent Cox is all over the Internet.

Images via Wikipedia.

New Yorkers Neurotic

Here are the ten modern neuroses affecting New Yorkers. Which is yours? Feel free to pick more than one.

Maybe Cat People Really Are Losers

“While visiting her mother in Pennsylvania this month, Lauren Pytel, a 47-year-old high school English teacher who lives in Tudor City, found herself pining for her cats, Tiggles ap Caduet and Munchie Effexorov, and their recently deceased siblings, Claritin and Zoloft.”

— Much like with Occupy Wall Street, when you’re a cat person, sometimes it’s real hard to deal with your fellow travelers. But yes: now you can play with the cats at Bideawee (a very fine shelter!) online, by means of the Internet. It’s just like going to a Brooklyn deli to pet cats, except you don’t get your hands dirty (or, you know, seltzer).

The Golden Age Of Dirty Talk

by Lili Loofbourow

It would never occur to me to describe ears as “handsome volutes to the human capital.” That it did to Charles Lamb, who also called them “ingenious labyrinthine inlets” and “indispensable side-intelligencers,” says one thing about him and something else entirely about me, but it says something, too, about the linguistic environment where volutes to the human capital can thrive. Whether because of the Internet or some other mysterious, homogenizing influence, our language has lost some biodiversity. Even our obscenities — the parts of language least likely to lose their verve — have dwindled, and the survivors have dulled from overuse. “You’ve got balls,” we say, when once we could have yelled that “the testimonies of your Manhood are swell’d as big, Sirrah, as a couple of Norfolk dumplings!” Where we use mean hypotheticals, like “I would love to have the ability to make you sore,” our ancestors promised each other nights spent “in prigging, wapping, and telling of drunken stories.”

To be clear: this isn’t about sexual repression; it’s about the sorry state of sexual expression. When did we forget how to talk dirty? Sexting transcripts are criminally boring. Craigslist ads read like chimp-generated remixes of the same five words. Is it the Internet? Why are Americans so bad at writing and speaking the thing they love thinking about and doing? You can measure a civilization’s cultural capital by how it encodes its basest operations. By that yardstick, we’re broke.

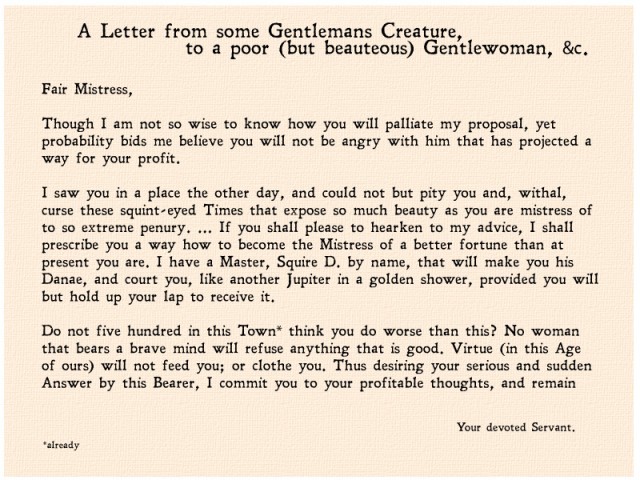

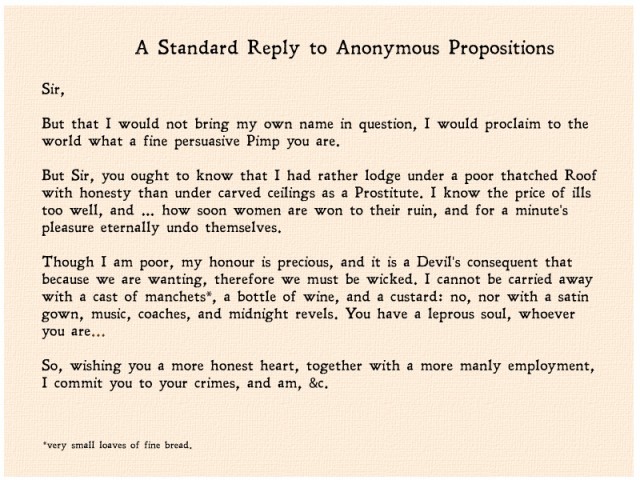

So, what would good bad language look like? Luckily, there was plenty of it in early modern London, where vulgarity had a vast vocabulary and even indecent proposals were decently couched. For an example of the latter we can look to a cheeky little pamphlet written in 1656 called the Academy of Pleasure. Author unknown (he knew better than to sign his name), it’s an etiquette book for the morally flexible. What it offers is a) practical guidance in the art of preying on others (and, pretty broad-mindedly, how to avoid being preyed on) and b) criminal panache. If a 17th-century Londoner tried to scam you, he’d do it by announcing (grandly, irresistibly): “I have a task worthy the pregnancy of your spirit.”

I have a task worthy the pregnancy of your spirit: Save the slangforest. Breed dirty words. Bring synonyms back. Or just enroll in the Academy of Pleasure.

FLUENT IN LACKLUSTERESE

We live in an impoverished wasteland of panda-like fucks so dull from overuse that they refuse to increase and multiply. It might be that the longer we swim in codes and memes, the blander our linguistic habitat becomes. The Internet is good for ideas, but synonyms don’t thrive in its universe. The web compresses language the way it compresses music into mp3s or images into GIFs. It’s efficient. Lossy.

Brevity breeds shorthand. Television steam-ironed the American accent, and so has the Internet. Stripped of eye contact and body language, one of the easiest ways to telegraph agreement is to echo word choice. The effect (within commenting communities, say) is a bizarre catalytic conformity. We all have more or the same voice online. Even if arguments proliferate, linguistic difference dwindles. Having settled on the rules of engagement, we’ve hung onto our disagreements but totally lost our ears.

We live in an impoverished wasteland of panda-like fucks so dull from overuse that they refuse to increase and multiply.

When Anthony Weiner writhed in the public eye, I watched, doubly dismayed — at his dishonesty on the one hand and the mundanity of his dirty talk on the other. Whatever his faults, Weiner has a long record as an articulate jokester; how could he have penned those uninspired, sub-literate half-sentences? Was it a lack of effort? A lack of interest? Or (and I think the truth lives here) is it that he’s never considered applying the high standards he has for political performance to other kinds of wordplay?

Why does language get tepid and ugly just when it should be doing the most sensory kind of work? Shouldn’t sexting be a petri dish of future Shakespeares, all dying to persuade, trying with words to transform bodies? It’s a kind of alchemy, after all; straw into gold, words into wood.

In The History of Sexuality, Foucault speculated that those who write about sex acquire some kind of revolutionary halo. If mentioning the unmentionable transgresses, those who do so “ardently conjure away the present and appeal to the future, whose day will be hastened by the contribution we believe we are making. Something that smacks of revolt, of promised freedom, of the coming age of a different law. Tomorrow,” Foucault says, “sex will be good again.”

He was right, but that moment came and went. These days, there’s no revolutionary halo inherited from obscenity, no promised freedom. The taboo limps along, not too relevantly, while millions of Dicks and Janes gabble about their genitals and porn habits and preferred positions with all the panache of misbehaving first-graders. I don’t know whether sex will be good again tomorrow, but wouldn’t it be great if one day, our way of talking about sex, and bodies generally, and other things too, was good again?

And before anyone brings up our wild and wacky modern sexual vocabulary, I acknowledge that yes, we’ve hyper-corrected for our prudish past with a laundry list of “positions” and acts that are just as static and resistant to recombination as our handful of naughty words. As poses, the reverse cowgirl and the dirty sanchez are bossy and instructional. Instead of Lego’s you can build anything with, they’re Paint by Numbers guides to “creative sex.”

Somebody might object here that that’s the point of positions. Actions speak louder than words. Normally I’d talk, just as originally, about the Eskimos and their zillion words for snow, and I’d try to and fail to prove that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was basically right, our thought is constrained by the language we have available. Instead, try this: write down your personal dirty-word arsenal (every one you’ve ever heard, not even restricting yourself to ones you personally use), and compare it with the list of country line dance steps here. I promise that list 2 will be longer, and that for every word you wrote down, you’ll find a word on that list — a ‘botafogo’ or a ‘swivet’ or a ‘sugarfoot’ that packs more energy, more possibility and more pleasure than the overworked monosyllables we use for sex (and insults! As if they weren’t tired enough). Without taking anything away from country line dancing, it’s embarrassing that a dance taught I learned in P.E. has a better and bigger vocabulary than all of sex.

Instead of pretending I’m hoping for a brighter future, I’ll just admit, again, that I’m holding the present up for scrutiny against a distant past. Once upon a time, before Victorianism punished synonyms gone wild, long before we pathologized euphemisms, things were different.

THE ACADEMY OF PLEASURE’S STUDY ABROAD PROGRAM

The Academy of Pleasure was (usefully, for those claiming to read it ironically) half reference-work, half joke-book. Its lack of organization was probably strategic; besides advice, it also included poems, letters and dialogues that you could either emulate or enjoy. The advice acknowledges two things many advice columns don’t: one, that the parties involved might not be moral paragons searching for an ethically perfect solution, and two, that even scoundrels want to sin with style.

The Academy advises you, for example, to refuse a known creep’s advances not by rejecting his advances, but by accepting his compliments provided they aren’t “glued to sinister cogitations.” (Since the creep’s cogitations are patently glutinous, you’ve effectively refused him, on his own terms.) When you see a lady you admire, you might announce, like one gentleman did, that “t’other day after I had seen you, my belly began to swell.” And if you’ve recently married and therefore need to break up with your backup lover, the Academy can help you there too. (It recommends a glacial “Yours in all civil service” for your valediction.)

The Academy’s strength is obviously its pragmatism. Suppose you made an assignation with a lady and forgot to keep it. Wasting no time on reproaches, the author advises you to start by praising your date’s “immaculate candor” which can “whiten the swarthiest crime.” Add that you’d sooner sacrifice your life to sorrow and death rather than add to your guilt “by apologizing for a sin that cannot be remitted.” By such slow and steady steps does the standard non-apology rise, like yeast, to a kind of art.

Now, if you’re on the receiving end of this variation on “I’m sorry you feel that way” (that timeless slab for undead arguments), the Academy of Pleasure can help you too. You might reply that your feckless lover “very aptly imitates those children who, having tied strings about the legs of their birds, sometimes suffer them to gain liberty to a great distance, but when they please twitch them home again.” Then you’d admit — skipping the customary steps of passive-aggression and denial — that you want him so much that “a slender excuse will serve where the injury is pardoned ere committed.” Crappy apology, but it worked since I’d forgiven you even before you screwed up. Finally, far from warning you to shun him in future, the Academy blithely models how to schedule your next assignation: “All the penance I shall impose is this,” its sample lady writes, “that you afford me a visit at my mansion tomorrow in the morning about the hour of ten.”

Thus and so did another age codify the ways and means of mending a botched booty call.

Back to Foucault: The History of Sexuality opens with an indictment of our “restrained, mute, and hypocritical sexuality” and describes the seventeenth century as a time when

“sexual practices had little need of secrecy; words were said without undue reticence, and things were done without too much concealment; one had a tolerant familiarity with the illicit. Codes regulating the coarse, the obscene, and the indecent were quite lax compared to those of the nineteenth century.”

An age that equips you with a template for soliciting sex from a woman down on her luck is special:

Again, the Academy includes, for the sake of completeness, the lady’s likely reply. (She’s all virtue in this case, but that doesn’t mean she can’t whip out a devastating burn.):

A RUFF BY ANY OTHER NAME

Even better than the etiquette and the letters — which are still formulas, after all — is the terrific arsenal of dirty language seventeenth-century people had at their disposal. I don’t know whether it was the atmosphere of increased tolerance Foucault described, or that linguistic communities hadn’t standardized to nearly the extent they have now, but whereas now we have d-words and c-words and ‘naughty bits,’ in the 1690s you could put your ‘spigot’ in a willing ‘well.’ Or offer to plop your ‘vagary’ onto someone’s ‘cabbage stump.’

In the 1690s, if you mentioned your ‘Kingo’ (or your ‘Rowley’) people would think of Charles II (or his prize stallion, Rowley) and all eyes would turn to your crotch.

There’s a school of thought that condemns euphemisms on the grounds that they’re mired in ‘sex-negative’ prudery and repression. That isn’t wrong, but it isn’t fair, either. The euphemism is older and messier than that, and we can expunge some from the lexicon without killing the genre outright. Whatever taxonomic merit there is in punctiliously calling our ‘umbles’ genitals and referring to our ‘runnions,’ ‘sticks,’ ‘satchels’ and ‘tinderboxes’ by their correct clinical terms (penis, penis, vagina, vagina, respectively), we should know, before we smugly rejoice in our freedom from inhibition, that in the 1690s, if you mentioned your ‘Kingo’ (or your ‘Rowley’) people would think of Charles II (or his prize stallion, Rowley) and all eyes would turn to your crotch.

As a lady, your ‘sack’ might be tickled by someone’s ‘Bloody Great Kidney Wiper,’ or you could welcome a rolling pin into your treasure. Parts shuffle and recombine in circumvolutory spirals: her ‘ruff’ to his ‘sweepstakes,’ his bilbo to her wheel. You could explore her terra incognita with your Robin. Invite his spoon into your tub. Mock a man’s rouncival, ride his rope, diddle his distaff. He might offer you his sap, or his slime — or, if he was feeling melancholy, his tear. If you were game, depending on your mood, you might offer him your ‘commodity’ or let him nuzzle your ‘tuzzy-muzzy.’ The fact that these all mean the same thing is an un-fact. The words refer to the parts we know, but just as there are nights when a lady’s ruff drives you wild, there are nights when it’s just a sack. Same goes for rouncivals and spigots.

Not that you would walk up to a stranger on the street and make the suggestion outright, obviously, although it was a rufty-tufty age. In one play, a nurse tells a nobleman that when she changed his baby and made him “clean about the secrets,” she smiled to see “that God had sent him in a plentiful manner.” Few nurses nowadays would congratulate a parent on the size of their infant son’s penis. Or add, by way of compliment, that “it put me half in mind of your worship.”

I could go on, but the point is that the words were there in abundance, suggestive, drippy, connotative, waiting patiently for their turn like players on a bench. The difference matters: if you describe an encounter as ‘a sickle in a sore,’ you’ve said everything.

In this respect, at least, the early modern pornosphere beats the higher-ups, up to and even including Shakespeare. Sure, he loved to use ‘quean’ for whore, but I don’t know how he resisted the other choices: a whore was also a suppository, a red petticoat, a rannel, a quail, a ramp, a stroller, a strum, a rump, a tiffany-trader, a trull, a punk, a trug, a trugmoldies and a traffic. Instead of ‘prick,’ why not ‘the Ass’s Tickle-Gizard,’ the ‘trowel,’ the ‘touch-tripe’? And as for ‘nothing,’ that word for a woman’s unmentionables, I submit that we move forward bearing in mind that for all the vagina’s many qualities, it’s not a rose by any other name. There’s more substance in a ruff, more poetry in a whibbob, and more impudence in a toby.

Sources:

• A Dictionary of Sexual Language and Imagery in Shakespearean and Stuart England by Gordon Williams

• Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London by James Grantham Turner

• A History of Sexuality: An Introduction by Michel Foucault.

Lili Loofbourow is a writer living in Oakland. She blogs as Millicent over here.

Top image courtesy of the English Broadside Ballad Archive