Heavy D, 1967-2011

Heavy D, 1967–2011

One of the nicest things about driving north out of the city is that point ten or fifteen minutes past the Bronx Zoo when you see the familiar sign and you say to yourself or the unlucky person who’s in the car with you and has had to hear you repeat your own silly little favorite sayings again and again and again for the past ten years, “Money Earnin’ Mt. Vernon!” It’s such a great rhyme, it rolls off the tongue perfectly, really one of the best municipal nicknames anyone’s ever come up with. Sadly, the man who grew up there who coined the phrase — or, at least, the man who brought it to my attention, and probably the greatest number of other peoples’ — died yesterday. The beloved rapper and actor Dwight Errington “Heavy D” Myers; he was 44. Which is way, way too young.

This is the first Heavy D song I ever heard.

Needless to say, Heavy paved the way for many other plus-size rap sex symbols. Most notably, the Notorious B.I.G., who famously name-checked him in his song, “Juicy” and featured him in the video for “One More Chance.”

Heavy wrote the theme song for In Living Color, too. That that J. Lo used to dance to every week.

He was a good dancer himself, Heavy, and the bright green rain gear he wore in the video for what would become the biggest hit of his career is simply astounding.

In the mid-’90s, he started acting, with rolls in Laurence Fishburne’s 1994 play Riff Raff and Charles S. Dutton’s “Roc” on TV. I remember being hugely impressed with his performance in Nick Gomez’s New Jersey Drive. “Don’t fuck with my groove!”

He would go on to have a substantial career on screen. You can go see him today, playing a courthouse guard with Ben Stiller and Eddie Murphy in Tower Heist.

But it’s music that he’ll be most remembered for. He was not the H-E-R-B, he was the H-E-A-V. And there’s nothing but those kinds of hearts in hip-hop today.

How Much Can You Demand?

by Matt Langer

There was a full house on hand last night at New York’s Housing Works Cafe and Bookstore for an Occupy Wall St. panel organized by n+1, Brooklyn’s hometown literary journal. The panel was larger than advertised, totaling seven in addition to moderator and n+1 progenitor Keith Gessen. A healthy mix of contributors were on board: there was the earnest, washed-up political wonk who’d been sleeping in Zucotti Park for a month now, the filmmaker who’d been downtown since the very first meeting, the SEIU representative and the education policy activist; there were youngs and olds, students and professionals, seasoned organizers and first time protesters.

The discussion all got started with a talk of origin stories after Gessen invited those who’d had the earliest involvement with the occupation to tell the audience of its genesis. These stories were already old hat for myself and others in the room who have obsessively followed OWS since its inception, but it turned out to be a valuable introduction nonetheless since — as we were to discover later during the Q&A period — there were a number of curious people in attendance still unfamiliar with what OWS is all about.

After this round of introductory niceties, in which panelists offered their take (or, in some cases, lack thereof) on how the movement came to be, what it meant and where it was going, Gessen showed a pair of videos seemingly arranged as a sort of point-counterpoint: first, a video of the October 25th occupation of New York City’s Panel for Educational Policy; and second, the now-viral footage of the October 26th arrest of a Citibank customer at her local branch shortly after having closed her account.

The videographer of the latter clip, who was seated on the panel, was invited to narrate the choppy footage, and her narration injected an eerie presence into a video much of the audience was already well familiar with, something that only served to reactivate that initial horror of watching public police forces step in on behalf of private business interests.

Gessen then invited the organizer of the Department of Education occupation — also sitting on the panel — to discuss those events at length, although the invitation came with a leading question: Gessen asked, in effect, to justify this thing he had found “disturbing.” And it was a fair question! Albeit one inexpertly answered: Bloomberg’s Panel for Educational Policy is a sham democracy, its members are unelected and unaccountable, mayoral appointments outnumber independent appointments, and therefore (therefore!) it was a meeting ripe for an occupation and a hostile takeover by the people’s mic. Members of the audience fidgeted, squirmed and pecked at iPhones as she hijacked the panel with a twenty-minute digression into the wonky minutiae of New York education policy and history; I fidgeted and squirmed at how her logic necessarily meant that every one of the tens of thousands of unelected and unaccountable executive staffers who head to Washington after we elect a president every four years should also be subject to precisely the same treatment (occupy next week’s FEC hearing! occupy the State Department! occupy the Supreme Court!).

The panel then followed with a lot of talk of the burning question: the subject of demands. There turned out to be so much to say on this subject that it dominated the rest of the evening right up until the Q&A period.

There would be no demands, the audience was reminded, most notably by Sarah Resnick, who offered up the boilerplate but still very eloquent explanation that to make demands of elected officials or of an established political system is to concede to either asking permission of those in power or to implicitly accepting to merely agitate within a system one deems improper, incorrect or otherwise less than preferable. And that’s a good thesis! The other panelists followed up with allusions to Mubarak (“The people in power always ask your demands first because they have the resources with which to pay you off”), standard issue conspiracy theorizing (“They’ve tried arresting us, they’ve tried scaring us off, they’ve tried pepper spraying us, and they’ve tried taking away our generators but now they’re running out of responses so their next tactic will be to turn us against ourselves and against each other”), and finally an effort to reconcile the demands of the movement at large (OWS as an umbrella makes no demands) with the demands of its constituent members (individuals and working groups of individuals can — and do! — make demands, demands that simply don’t reflect on OWS on the whole).

And it was when these individuals spoke, individually, of their individual demands that I began to worry, because despite how radical Resnick’s formulation is, the specific demands that did get tossed out by other panelists were, sadly, not so much: student loan reform, higher tax rates for billionaires, a job for everyone, and so on. And this is a problem! Because this very honorable formulation of why the movement cannot make demands (a refusal to cooperate with existing rulers and the structural status quo) was being trumpeted by people who will very happily talk out of the other side of their mouths in specifics that couldn’t possibly pertain more to existing economic and political structures and leadership (“We won’t make demands of our elected leaders because we don’t want to ask their permission, but we will ask our corporate leaders to give us all jobs”).

Moreover, the reasoning behind not making demands most certainly does not preclude making demands of our collective imagination, and yet the majority of these panelists demonstrated very little willingness to think big, to think long-term. On the contrary, contributors took pride in not discussing ends, because ends in themselves are as problematic as demands are in this complicated relationship between the movement and the status quo. The one occupier on the panel, Haywood Carey, who’d spent the past month sleeping in Zucotti, returned on numerous occasions to the merits of “small-’d’ democracy,” “leaderless movements” and “consensus based decision making,” emphasizing them with sufficient frequency as to solicit at least a couple of visible eyerolls in my immediate vicinity. He even went so far as to suggest — confusing for a moment the temporal and the teleological — that were the movement’s end to come tomorrow it would already be a success, because now the people were talking, the people were busy doing their small-’d’ democracy.

In a twist on the old Machiavellian traditional, the means had become the ends, and in the process he exposed two enormous problems the movement faces.

First, while its refusal to make any specific demands is admirable, that stand becomes problematic when a movement’s constituent members demonstrate a worrisome lack of courage to imagine any alternatives or to conceive of the mere possibility of making demands outside of existing political and economic structures. Only one panelist last night even got close to enunciating an alternative, when Meaghan Linick, the videographer behind the Citibank arrest, mentioned that she and her friends, ideally, would conceive of the movement’s end as a more equitable system fully re-architected from the ground-up (she did not, unfortunately, have a chance to go into specifics).

Secondly, the movement faces an enormous organizational and operational hurdle in the way it fetishizes its working groups and horizontal structure and lack of leadership and rejection of narratives, because this granular, piecemeal approach not only limits the movement’s prospects but necessitates that whatever change it effects remain local in three dimensions: the geographic, the chronological, and the ideological. It will only ever — by its own insistence! — make baby steps; it won’t (and can’t!) be starting the revolution. And this exposes a massive internal inconsistency, because a movement so committed to not making demands of the status quo because of its Bartleby-esque refusal to participate has also imposed an arbitrary upper bound not only on what it can accomplish but on where, exactly, and in what sort of world it may be accomplished.

Now one of the great promises of the Occupy movement (that is, at least, for me, someone who willingly admits to projecting his radical leftism on a movement at least nominally uninterested in having any of it) is where it stands in the historical trajectory of post-’68 organizing, a sort of soothing synthesis to the thesis/antithesis of the now-clichéd fracturing of the Seventies left and, later, the violent ineffectuality of the G8 protests. Here now is (at last!) a peaceful movement offering a uniquely simple, comprehensible and, at least according to public polling, widely agreeable message: the problem is money. Which is a lovely and long-awaited contrast to the history of the left over the last four decades, a time defined by internal battles among leftists to determine which issue would sit atop the movement’s pantheon rather than uniting against the material conditions in place that adversely affected all of them.

And yet from what I saw last night — and, frankly, what I’ve seen from a lot of the movement thus far — the majority of these panelists were content to just go through the same old motions, to patch the leaks on the sinking ship until the next time the moneyed elite slowly punch holes in the hull once again.

Slavoj Žižek editorialized in The Guardian recently that “one of the great dangers the protesters face is that they will fall in love with themselves.” I was reminded of those words last night, worried that this danger had already been realized as panelist after panelist congratulated either the movement’s commitment to “little-’d’ democracy” or its unwillingness to issue demands. The movement has already proven beyond a shadow of a doubt that it’s got a great short game, but I worry those tactics can’t survive the long haul (not to mention the fast-approaching winter). I worry if a group of people generally either unwilling or unable to think beyond the status quo can ever drastically alter it. Mostly, though, I just worry that this uniquely and enormously promising moment will go to waste because a movement so busy falling in love with itself for being horizontal and leaderless will forever remain a movement in which no one person speaks as a representative — and, as a result, will ultimately remain a movement in which anyone who speaks at all speaks representatively — because by and large I’m not convinced the representatives I’ve seen so far could answer the only real question: “What is to be done?”

Matt Langer is a technologist and writer living in Brooklyn who really just wishes Keith Gessen and Astra Taylor had talked more last night.

Photo by Timothy Krause.

Silvio Berlusconi Will Soon Have More Time To Party With Hookers

Silvio Berlusconi Will Soon Have More Time To Party With Hookers

“Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi has said he will step down after the next budget is approved by Parliament, a statement from the president’s office said Tuesday, marking a painful end to his long dominance of Italian politics.” OR IS IT?

Here's Chad Harbach Teaching You How to Make Homemade Protein Bars

by The Awl

Cooking the Books has been directed by Valerie Temple and shot and edited by Andrew Gauthier, tireless and wonderful people both. You can see all the Cooking the Books episodes here or even subscribe via iTunes. Some previous highlights: Will Leitch Makes Tofu Dogs; Julie Klausner Makes Kugel; Tao Lin Makes Raw Salad; Jennifer Egan Makes Macaroons; Sam Lipsyte and Ceridwen Morris Make Momofuku Pork Buns; and Julie Powell Makes Valentine’s Day Liver.

Canada Apparently Has Its Own Loch Ness Monster

Is this footage proof of the existence of the Ogopogo, Canada’s legendary aquatic beast? Sure, why the hell not.

Things You May Not Have Known About 'Blue Velvet'

Huh! Megan Mullally was originally in Blue Velvet. Who knew?

It's Working: Wisconsin's Recall to End all Recalls

by Abe Sauer

Recall is the new Occupy. Today, seven states will see at least 26 separate recalls in 11 jurisdictions. And starting November 15th, a massive Wisconsin-wide petition drive will attempt to fulfill a promise from February to recall Governor Scott Walker. It’s a massive undertaking, and there is reason to believe it will succeed, but also reasons it will fail. Once filed, the recall effort will have 60 days to —

Suckers! On the afternoon of Friday, October 4th, a former Walker donor submitted a petition to recall the governor under the committee name “Close Friends to Recall Walker.” The filing, which noted it was done “to fulfill my friend’s last request,” triggers a rule allowing Walker unlimited fundraising during the 60-day period and comes, magically, days before Walker begins a fundraising trip to, amongst other places, California, Arizona and Wichita. (Gee, what’s in Kansas?)

In late October, Public Policy Polling assessed the prospects of a successful Walker recall as “dimming.” The PPP called Walker “still not popular” but noted that 49 percent were opposed to a recall. Further, the group could not find a single challenger who would best him. Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett, his 2010 challenger, falls short, 48-to-46 percent. That’s down from a 50–43 advantage in May. Democrats’ last great hope, Russ Feingold, has declined to run for either governor or Herb Kohl’s senate seat, happy instead to martyr himself in a doomed crusade to convince both parties to stop accepting so much campaign cash.

An October Wisconsin Policy Research Institute (WPRI) poll of Wisconsinites found 49 percent did not support a recall, while 47 percent did.

But that same poll found that though 42 percent “strongly” or “somewhat” approve of how Walker “is handling his job as Governor of Wisconsin,” a full 45 percent “strongly disapprove.”

WPRI is one of those conservative “free market” organizations that puts “Institute” in its name so dim people think it’s research extends beyond hypotheses like “How much money can we get for this study?” PPP, meanwhile, is a leftist pinko propaganda organ. With the sampling error basically washing out any meaning, these polls tells us nothing about what’s to come, except more polls.

In liberal Madison, yard and window signs calling for the governor’s recall are commonplace. But then, as the governor himself has said, “You’ve got a world driven by Madison, and a world driven by everybody else out across the majority of the rest of the state of Wisconsin.” (This idea that a state’s major metropolis is not a “real” part of its state is not just for New Yorkers anymore! A Minnesota supreme court judge recently said the same about the Twin Cities.)

In what the governor considers “real” Wisconsin, Recall Walker bumpers stickers and signs are not as common, but not completely absent. In part, this is because Walker enjoys a lot more support outside Madison (and Milwaukee). It is also because, in smaller towns, residents forced to live in proximity work hard to avoid open conflict. When petitioners go door to door and small-towners are given the private opportunity to speak, anything could happen. Just be careful out there petitioners: Wisconsin’s new concealed carry gun law was just complemented by new “castle doctrine” legislation. Were you just asking for a signature or did the homeowner act reasonably against you with deadly force? Who knows!

To listen to state Democratic Party Chair Mike Tate is to believe Walker’s defeat is a foregone conclusion. Many Recall Walker supporters are realistic about their enthusiasm. Yet four or five of the state’s politics bloggers I spoke with privately expressed skepticism about the uphill battles of both getting all of the signatures and then actually beating the governor.

While all of the attention is on Walker, Democrats will likely try and recall a number of state senators and representatives as well. The governorship may be the jewel in the crown. But with the 17–16 control of the state senate, the successful recall of one Republican would put Democrats in position to counter and block all Walker legislation going forward.

If mutually assured destruction was good enough for the Cold War, it’s good enough for Wisconsin. Republican state leaders have also expressed interest in recalling as many Democrats as possible. In November, 11 Republicans will qualify for recalls. Six Democrats in office for more than one year, the requirement for recall, will also be vulnerable. Another four Democrats and two Republicans who saw recall efforts against them fail for ample signatures will also be eligible. That is all in addition to the nine senators (three Democratic and six Republican) who were recalled this summer.

Meanwhile, Republicans, who still control both houses even after the successful recall of two state senators this summer, have become the Natasha and Boris of legislative bodies. When not hemming and hawing over where Wisconsinites will and will not be able to pack heat, Walker’s allies are scheming up any dastardly plan possible to trip up the recall effort. In this respect, the Wisconsin legislature has become an M.C. Escher drawing of strategic incompetence.

Mary Lazich, R-New Berlin, has become a one-senator anti-recall superstar. NFL commentators would say she’s “got a lot of motor.”

First, she proposed a new law requiring petitions with recall signatures be officially notarized. Then, Lazich proposed another law that would activate the new district maps for senators, but not for the Assembly, effectively setting up different recall rules for the state’s two legislative bodies. Proving herself a budding satirist, Lazich said of the proposal, “We can’t have disenfranchisement going on.” No, we cannot, which is probably why, back in 2000, Lazich voted for a bill that deleted the requirement that circulators of nomination papers or election-related petitions make an affidavit under oath.

But that stipulation is nothing next to the Republican interpretation of its own recently-passed electoral redistricting plan.

The gerrymander bill passed this summer clearly states, “This act first applies, with respect to special or recall elections, to offices filled or contested concurrently with the 2012 general election.” But now, Republicans are pushing to use the redistricted map for the upcoming recall battle, well prior to next November.

The Government Accountability Board has taken the outrageous position that any recalls take place under the old district maps, just as the new law states. It’s a decision that has brought the wrath of the state chapter of the Club for Growth, which called the board’s decision — a decision that follows the very bill Republicans passed just months ago — a conspiracy of “The Saul Alinsky school of political vandalism” to create chaos so that “the radicals take what they want.”

This Keystone Cops slapstick suggests the possibility that the Republicans will take legal action against their own just-passed law in order to make any recalls more difficult. As Wisconsin politics and law blogger Illusory Tenant put it: “Wisconsin Republicans Get Set to Sue Themselves.”

Then, on Halloween, Senator Lazich did everyone one better. The senator suggested the new districts be enacted immediately only for senators, with the assembly districts left to follow the rules as Republicans wrote them earlier this year. But wait, there’s less! In her case for a batty re-sorting of district rules, Lazich repeatedly cited, to make her case, a pending federal lawsuit against the entire redistricting bill on the grounds of its unconstitutionality. To be clear, to obstruct the recalls, a Wisconsin state senator was citing a lawsuit against a bill that she had authored and passed.

But then, how is a humble state Senator to keep so many elections rules straight? It’s not as if Lazich is the chair of the state senate’s elections committee. What’s that? Lazich is the chair of the elections committee? Oh my.

Lazich’s effort was defeated by the one vote of Senator Dale Schultz. Schultz, a moderate Republican who came out against the governor’s union-busting budget bill earlier in the year, has come to be known as “Governor Schultz” because of the tie-breaking vote power he holds following the recall loss of two GOP state senators in August. (One of those recalled state senators, Randy Hopper, recently celebrated his new unemployment with a post-Packers game DUI, during which he told the officer, “Never run for office.”)

“Time for him to be thrown out of office,” wrote conservative Victor Janicki on Facebook, about Schultz’s vote. The night after the vote, the windows of Schultz’s Capitol office were hit with eggs. (It was the latest salvo in Wisconsin’s battle of ingestibles. In September, a GOP man wearing a dress poured a beer on a Republican state senator in a bar. Conservatives later auctioned the dress on eBay for $255, which was donated to a Walker campaign fund.)

The Government Accountability Board meets on Wednesday, November 9th, to discuss how redistricting will mesh with any recalls. Activists are worried a fast-one will be pulled favoring the new districts. Reid Magney, the Board’s public information officer, assured me that since Schultz blocked Lazich’s bill, no changes will be made at the meeting and any recalls filed in the immediate future would go forward under the old districts. But Magney noted that should recalls against individual senators be filed, say, next June, the new districts may go into effect to avoid mass confusion with the 2012 general election.

While the unions and activists for the Walker recall have been preparing their effort, a small group of activists have maintained a constant protest presence at the Capitol. At the Facebook page “Shit Scott Walker is Doing to My State,” videos are posted nearly daily of some activist arrested for videotaping in the legislative chambers. When a 12-year-old was threatened with arrest for doing her homework in the gallery, with a message scrawled on the back of her notebook, it was seen as the height of idiocy. That idiocy is either the police state that’s been created inside the Capitol or young children used to make a political point. Pick your poison.

November 1 was “Concealed Camera Day,” when 18 were arrested in the Assembly gallery for possessing photographic equipment. The event coincided with the first day concealed handguns were allowed in the Capitol. When he took a photo of another demonstrator being arrested, the editor of The Progressive, Matt Rothschild, was himself arrested (meta-arrested?). The subsequent court hearings for those arrested have been an embarrassing circus, with prosecutors not always sure what the charges are. These actions have helped maintain some momentum through the dry months after the first recalls. But the actions have also hardened pro-Walker forces, who don’t necessarily see any difference between the anti-Walker activists and the Occupy Wall Street movement.

Whether or not the Occupy Madison movement will join with the recall effort is unclear. Quite honestly, the Occupy efforts in Madison have, if anything, handicapped the recall’s reputation. The peak moment of face-in-palm embarrassment was when the Occupy Madison protesters were denied a fresh permit. Now, to have a protest permit revoked in the People’s Republic of Madison takes an extraordinary act, like, say, jerking off in front of people or something. (Handily, public masturbation was cited as one of the complaints about the protesters. )

And the logistics facing the recall are daunting. Currently, volunteers are being trained to collect 540,206 signatures, according to the rules, in 60 days across 72 counties. The recall movement has the distinct advantage of a massive existing activist infrastructure from the spring protests as well as the subsequent summer recalls. This foundation — its lists, phone banks and volunteers — will be leveraged quite quickly to gather signatures. As the movement stretches for the sprint, some inside have begun grumbling about what they see as a Democratic Party highjack.

Several major groups have spearheaded the recall drive, amongst them political action committees United Wisconsin, the Committee to Recall Scott Walker and We Are Wisconsin. Recall activities are being coordinated by the coalition group United Wisconsin, a group some “grassroots” activists feel has been taken over by the state’s Democratic Party.

One gripe is that the party is being less than open about the process. One example an activist gave me is that “They are now running a recall training program that is less than transparent. One can not even write about it after leaving the meetings.”

One of those upset with the Democratic Party’s “highjacking” told me that certain other groups were considering filing their own recall petitions. A sort of protest filing, these groups would trigger their own 60 day windows. So, by the time the United Wisconsin files on Nov. 15, there could be as many as three, four, or even ten different official recalls.

This is important because while different recall groups can combine signatures, those signatures must all have been collected in the same 60 day period. And since any recall submission is sure to involve every lawyer in Wisconsin, it’s just another way things could go wrong.

The Wisconsin Democratic Party did not respond to requests for comment. Nonetheless, the activist who spoke to me about dissension about the recall’s new top-down management style is optimistic about the recall’s chances. He told me all involved might “just ‘kill’ each other” but added that “we’ll get the signatures — all the drama aside.”

Speaking of killing each other, did I mention that Wisconsin has gone gun crazy? After being one of only two states left without a concealed carry law, as of November 1, visitors can just assume all Wisconsinites are packing heat. (No joke, that is the NRA’s logic for the increased lawfulness provided by concealed carry.)

By just the fourth day, 20,381 had applied for a permit. Originally, the emergency rules for carrying a concealed gun required four hours of instruction with a weapon. Those rules were suspended soon after by a legislative committee. That means pointing a gun at someone now fulfills the time requirement for concealed carry training.

Amidst all the gun talk, some dope on a recall Walker Facebook page wrote, “Rather than recall him… Can we kill him instead? Just curious.” Despite a toxic atmosphere of partisan spite, hope for a cooperative future Wisconsin was evident when parties on both sides had a good laugh at the single doofus remark on Facebook. Just kidding.

“Governor Walker Target of Online Death Threat” read the MacIver Institute headline. No question mark. A day later, Capitol Police said they were interviewing the poster. Literally 30 minutes after that statement came another, announcing that 200 rounds of live ammunition had been found at a Madison elementary school playground. “This will only end in something,” said everyone.

The one sure thing is that nobody in Wisconsin seems particularly concentrated on “job creation” right now. Even the hopeless Democrats seem far more concerned with the noble, if cloudy, First Amendment battle over allowing cameras in the Assembly gallery. The failure to create jobs may ultimately torpedo the USS Walker. The governor promised 250,000 private sector jobs in his first four years. After nine months, he’s at just 29,300.

Wisconsin may be struggling to bring jobs back to the state this year, but one industry the state has excelled at is the process by which a dollar bill is manufactured into a TV issue ad.

The nine Senate recalls cost state and local governments just over $2 million to facilitate — but more than $44 million was spent on campaigns and third party issue ads.

The petition to recall the governor by a former Walker donor follows a summer when Republicans ran fake candidates to force Democratic primaries , bleeding out more fundraising time. Walker is now free to raise unlimited funds through all 60 days of each recall filled against him. This fundraising can continue through the GAB’s 31-day signature certification period — a period Magney more or less promised me would take at least twice that long. Any other recalled politician will also be allowed unlimited fundraising during the petition period.

One detail Magney stressed is that while those threatened with recall may raise unlimited funds during the signature collection process, any of that money beyond regular limits ($10,000 per individual or $43,000 per committee) must be spent to combat the recall. After the certification process, funds raised over the usual caps can only be spent on legal fees pertaining to the recall petition. That means all those unlimited funds are like Cinderella. After midnight it turns back into plain old limited funds. For example, if David Koch gives Walker $10 million next week, Walker can only use $10,000 of that during any recall campaign. The governor must spend the other $9,990,000 on anti-recall ads — or what Magney called “positive image ads.”

With a flood of unlimited money for more ads, the governor may be able to afford the real Morgan Freeman.

Then again, recall candidates may not get spit. The trend in Wisconsin is entire elections controlled by third-party messaging. Hell, why give money to a candidate for messages not absolutely under one’s control when messages that you’re absolutely sure to control can be bought directly?

For the last few weeks, Americans for Prosperity and The MacIver Institute have teamed to sponsor the pro-Walker campaign “It’s Working.” Consisting of a website, banner ads and TV commercials, “It’s Working” is “committed to providing the facts to Wisconsin taxpayers.”

A nicer term for “lipstick on a pig,” a “positive image ad” is any that aims to positively spin an issue. In countries we joke about with leaders who wear sunglasses and/or a lot of medals, these ads are called “propaganda” and often come from an arm of government with the term “ministry” in its name.

So far, most of Walker’s supporters believe his reforms have magically transformed the state into a budget-balanced job-creating juggernaut in the space of just six months. To back this up, Walker has leaned heavy on how reforms have saved school districts millions of dollars. The Kaukauna School District has been the poster child for Walker’s reforms, which the governor and “It’s Working” claim left the school with a $1.5M surplus. Closer examination proves the school district maybe saved nothing and almost certainly handicapped itself forever. Meanwhile, the Elmbrook School District Walker claims as a savings success actually achieved those savings by closing one of its popular schools. It’s working!

Getting Walker supporters and those on the fence to believe “it’s working” long enough to beat the recall is the current goal of the administration. And that’s working. But Wisconsin has always been a state where political winds change first and this cycle seems to be going faster than ever. The first crack: State Tea Party-endorsed Rep. Reid Ribble (R-8) has begun working with House Democrats . Then the former roofer hauled his huge testicles over to the Christian Science Monitor and trashed Grover Norquist’s tax pledge.

If the governor is fazed by a state that’s so divided by his existence that his very name is now a battle call or profanity, he’s either too confident or too dim to show it. Walker’s reply to all of the criticism about flailing jobs promises, animosity and a pending recall effort: The capitol tree’s official name will change from “holiday” to “Christmas.”

Abe Sauer can be reached at abesauer at gmail dot com. He is also on Twitter. His book How to be: NORTH DAKOTA is out this month.

Deer Really Wanted Tacos

Attention every other local news reporter in America: THIS is how you do it.

A Conspiracy of Hogs: The McRib as Arbitrage

What the McRib says about us as a society is worse than any conspiracy theory

by Willy Staley

One of McDonald’s most divisive products, the McRib, made its return last week. For three decades, the sandwich has come in and out of existence, popping up in certain regional markets for short promotions, then retreating underground to its porky lair — only to be revived once again for reasons never made entirely clear. Each time it rolls out nationwide, people must again consider this strange and elusive product, whose unique form sets it deep in the Uncanny Valley — and exactly why its existence is so fleeting.

The McRib was introduced in 1982–1981 according to some sources — and was created by McDonald’s former executive chef Rene Arend, the same man who invented the Chicken McNugget. Reconstituted, vaguely anatomically-shaped meat was something of a specialty for Arend, it seems. And though the sandwich is made of pork shoulder and/or reconstituted pork offal slurry, it is pressed into patties that only sort of resemble a seven-year-old’s rendering of what he had at Tony Roma’s with his granny last weekend.

These patties sit in warm tubs of barbecue sauce before an order comes up on those little screens that look nearly impossible to read, at which point it is placed on a six-inch sesame seed roll and topped with pickle chips and inexpertly chopped white onion. In addition to being the outfit’s only long-running seasonal special and the only pork-centric non-breakfast item at maybe any American fast food chain, the McRib is also McDonald’s only oblong offering, which is curious, too — McDonald’s can make food into whatever shape it wants: squares, nuggets, flurries! Why bother creating the need for a new kind of bun?

The physical attributes of the sandwich only add to the visceral revulsion some have to the product — the same product that others will drive hundreds of miles to savor. But many people, myself included, believe that all these things — the actual presumably entirely organic matter that goes into making the McRib — are somewhat secondary to the McRib’s existence. This is where we enter the land of conjectures, conspiracy theories and dark, ribby murmurings. The McRib’s unique aspects and impermanence, many of us believe, make it seem a likely candidate for being a sort of arbitrage strategy on McDonald’s part. Calling a fast food sandwich an arbitrage strategy is perhaps a bit of a reach — but consider how massive the chain’s market influence is, and it becomes a bit more reasonable.

Arbitrage is a risk-free way of making money by exploiting the difference between the price of a given good on two different markets — it’s the proverbial free lunch you were told doesn’t exist. In this equation, the undervalued good in question is hog meat, and McDonald’s exploits the value differential between pork’s cash price on the commodities market and in the Quick-Service Restaurant market. If you ignore the fact that this is, by definition, not arbitrage because the McRib is a value-added product, and that there is risk all over the place, this can lead to some interesting conclusions. (If you don’t want to do something so reckless, then stop here.)

The theory that the McRib’s elusiveness is a direct result of the vagaries of the cash price for hog meat in the States is simple: in this thinking, the product is only introduced when pork prices are low enough to ensure McDonald’s can turn a profit on the product. The theory is especially convincing given the McRib’s status as the only non-breakfast fast food pork item: why wouldn’t there be a pork sandwich in every chain, if it were profitable?

Fast food involves both hideously violent economies of scale and sad, sad end users who volunteer to be taken advantage of. What makes the McRib different from this everyday horror is that a) McDonald’s is huge to the point that it’s more useful to think of it as a company trading in commodities than it is to think of it as a chain of restaurants b) it is made of pork, which makes it a unique product in the QSR world and c) it is only available sometimes, but refuses to go away entirely.

If you can demonstrate that McDonald’s only introduces the sandwich when pork prices are lower than usual, then you’re but a couple logical steps from concluding that McDonald’s is essentially exploiting a market imbalance between what normal food producers are willing to pay for hog meat at certain times of the year, and what Americans are willing to pay for it once it is processed, molded into illogically anatomical shapes, and slathered in HFCS-rich BBQ sauce.

The McRib was, at least in part, born out of the brute force that McDonald’s is capable of exerting on commodities markets. According to this history of the sandwich, Chef Arend created the McRib because McDonald’s simply could not find enough chickens to turn into the McNuggets for which their franchises were clamoring. Chef Arend invented something so popular that his employer could not even find the raw materials to produce it, because it was so popular. “There wasn’t a system to supply enough chicken,” he told Maxim. Well, Chef Arend had recently been to the Carolinas, and was so inspired by the pulled pork barbecue in the Low Country that he decided to create a pork sandwich for McDonald’s to placate the frustrated franchisees.

But the McRib might not have existed were it not for McDonald’s stunning efficiency at turning animals into products you want to buy.

As McDonald’s grows, its demand for commodities also grows ever more voracious. Last year, Time profiled McDonald’s current head chef, Daniel Coudreaut (I know what you’re thinking: two Frenchmen have been Executive Chef at McDonald’s? But no, Chef Coudreaut is American, while Chef Arend is a Luxembourger), whose crowning achievement so far has been turning a Big Mac into a burrito. In his test kitchen, we learn, a sign hangs that reads “It’s Not Real Until It’s Real in the Restaurants,” reminding chefs and cooks that their creations, no matter how tasty and portable they may be, must be scalable — above all else.

When the Time reporter visited the kitchen, Chef Coudreaut was cooking a dish that involved celery root — a fresh-tasting root that chefs love for making purees in the fall and winter. Chef Coudreaut proves to be quite a talented cook, but Time notes that “there is literally not enough celery root grown in the world for it to survive on the menu at McDonald’s — although the company could change that since its menu decisions quickly become global agricultural concerns.”

(Want to make enemies quickly? Tell this to the woman at the farmer’s market admiring the rainbow chard. Then remind her to blanch the stems a few minutes longer than the leaves — they’re quite tough!)

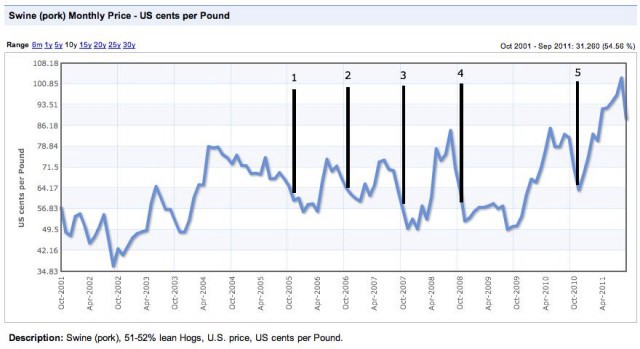

Now, take a look at this sloppy chart I’ve taken the liberty of making. The blue line is the price of hogs in America over the last decade, and the black lines represent approximate times when McDonald’s has reintroduced the McRib, nationwide or taken it on an almost-nationwide “Farewell Tour” (McD’s has been promising to get rid of the product for years now).

Key: 1. November 2005 Farewell Tour; 2. November 2006 Farewell Tour II; 3. Late October 2007 Farewell Tour III; 4. October 2008 Reintroduction; 5. November 2010 Reintroduction.

The chart does not include pork prices leading into the current reintroduction of the McRib, but it does show it on a steep downward trend from August to September. Prices for October, 2011 hogs have not been posted yet, but I suspect they will go lower than September — pork prices tend to peak in August, and decline through November. McDonalds, at least in recent years, has only introduced the sandwich right during this fall price decline (indeed, there is even a phenomenon called the Pork Cycle, which economists have used to explain the regular dips in the price of livestock, especially pigs. In fact, in a 1991 paper on the topic by Jean-Paul Chavas and Matthew Holt, the economists fret that “if a predictable price cycle exists, then producers responding in a countercyclical fashion could earn larger than ‘normal’ profits over time… because predictable price movements would… influence production decisions.” At the same time, they note that this behavior would eventually stabilize the price, wiping out the pork cycle in the process).

Looking further back into pork price history, we can see some interesting trends that corroborate with some McRib history. When McDonald’s first introduced the product, they kept it nationwide until 1985, citing poor sales numbers as the reason for removing it from the menu. Between 1982 and 1985 pork prices were significantly lower than prices in 1981 and 1986, when pork would reach highs of $17 per pound; during the product’s first run, pork prices were fluctuating between roughly $9 and $13 per pound — until they spiked around when McDonald’s got rid of it. Take a look at 30 years of pork prices here and see for yourself. Also note that sharp dip in 1994 — McDonald’s reintroduced the sandwich that year, too. Though notably, they didn’t do so in 1998.

(I’m sure all the sharp little David Humes among us are now chomping at the bit — and you’re right to do so! This proves nothing. It is just correlation — and the sandwich doesn’t always appear when pork prices are low. In fact, the recent data could prove that McDonald’s actually drives pork prices artificially high in the summers before introducing the sandwich — look at 2009’s flat summer prices. Could that be, in part, because there was no McRib? On the other hand, food prices were flat across the board in 2009 so probably not. So, no, this correlation proves nothing, but it is noteworthy.)

Because we don’t know the buying patterns — some sources say McDonald’s likely locked in their pork purchases in advance, while others say that McRib announcements can move lean hog futures up in price, which would suggest that buying continues for some time — and we can’t seem to agree on what the McRib is made of — some sources say pork shoulder, others say a slurry of offal — it’s hard to really make any real conclusions here.

The one thing we can say, knowing what we know about the scale of the business, is that McDonald’s would be wise to only introduce the sandwich (MSRP: $2.99) when the pork climate is favorable. With McDonald’s buying millions of pounds of the stuff, a 20 cent dip in the per pound price could make all the difference in the world. McDonald’s has to keep the price of the McRib somewhat constant because it is a product, not a sandwich, and McDonald’s is a supply chain, not a chain of restaurants. Unlike a normal restaurant (or even a small chain), which has flexibility with pricing and can respond to upticks in the price of commodities by passing these costs down to the consumer, McDonald’s has to offer the same exact product for roughly the same price all over the nation: their products must be both standardized and cheap.

Back in 2002, McDonald’s was buying 1 billion pounds of beef a year. (As of last year, they were buying 800 million pounds for the U.S. alone.) A billion pounds of beef a year is 83.3 million pounds a month. If the price of beef is abnormally high or low by 10 cents a pound, that represents an $8.3 million swing (which McDonald’s likely hedges with futures contracts on something like beef, which they need year-round, so they can lock in a price, but this secondary market is subject to fluctuations too).

At this volume, and with the impermanence of the sandwich, it only makes sense for McDonald’s to treat the sandwich as a sort of arbitrage strategy: at both ends of the product pipeline, you have a good being traded at such large volume that we might as well forget that one end of the pipeline is hogs and corn and the other end is a sandwich. McDonald’s likely doesn’t think in these terms, and neither should you.

But when dealing with conspiracy theories, especially ones you aren’t quite qualified to prove, one must always consider other possibilities, if only to allow them to reinforce your nutty beliefs.

Counter Theory 1: An obvious reason that the McRib might be a fall-only product could be that people have barbecue (or at least things slathered in barbecue sauce) all the time over the summer — they would be less likely to settle for a cheap and intentionally grotesque substitute when they can have the real thing. Introduce it in the fall and you might catch that associative longing for the summer that HFCS-laden spicy sauces and rib-shaped things evoke.

To this I say: but what about winter?

Counter Theory 2: Another counter-theory comes from an online forum, where all good and totally reliable information comes from on the Internet. Here, an alleged graduate from Hamburger University claims that the McRib’s impermanence has nothing to do with pork prices, but rather that it’s a loss leader for McDonald’s — the excitement of a limited-time-only product gets people in the door, as we have noted, and they’ll probably buy the big drinks and fries with the Monopoly pieces on them because they’re, on average, impulsive and easy to fool.

To this I say: I knew that sandwich was a low margin product! All the more reason for McDonald’s to time it properly with price swings.

Counter Theory 3: The last, and most obvious, explanation is the official version of the story: the sandwich has a cult following, but it’s not that popular. Like “Star Trek,” “Arrested Development” and that show about Jesus Christ returning to San Diego as a surfer, the McRib was short-lived because not enough people were interested in it, even though a small and vocal minority loved it dearly. And unlike these TV shows, which involve real actors and writers with careers to tend to, the McRib needs only hogs, pickles, onions and a vocal enough minority who demand the sandwich’s return, and will even promote it for free with websites, tweets and word-of-sauce-stained-mouth.

We’re marks, novelty-seeking marks, and McDonald’s knows it. Every conspiracy theorist only helps their bottom line. They know the sandwich’s elusiveness makes it interesting in a way that the rest of the fast food industry simply isn’t. It inspires brand engagement, even by those who do everything they can to not engage with the brand. I’m likely playing a part in a flowchart on a PowerPoint slide on McDonald’s Chief Digital Officer’s hard drive.

Ultimately what the McRib says about us as a society is perhaps worse than any conspiracy theory about pork prices. The McRib, born at the end of the Volcker Recession, a child of Reagan’s Morning in America, has been with us on and off over the last three decades of underregulated corporate growth, erosion of organized labor, the shift to an “ideas” economy and skyrocketing obesity rates. The McRib is made of all these things, too. When you think back to its humble origins, as both an homage to Carolina style pork barbecue, and as a way to satisfy McNugget-hungry franchises, it’s all there.

Barbecue, while not an American invention, holds a special place in American culinary tradition. Each barbecue region has its own style, its own cuts of meat, sauces, techniques, all of which achieve the same goal: turning tough, chewy cuts of meat into falling-off-the-bone tender, spicy and delicious meat, completely transformed by indirect heat and smoke. It’s hard work, too. Smoking a pork shoulder, for instance, requires two hours of smoking per pound — you can spend damn near 24 hours making the Carolina style pulled pork that the McRib almost sort of imitates.

And for its part, the McRib makes a mockery of this whole terribly labor-intensive system of barbecue, turning it into a capital-intensive one. The patty is assembled by machinery probably babysat by some lone sadsack, and it is shipped to distribution centers by black-beauty-addicted truckers, to be shipped again to franchises by different truckers, to be assembled at the point of sale by someone who McDonald’s corporate hopes can soon be replaced by a robot, and paid for using some form of electronic payment that will eventually render the cashier obsolete.

There is no skilled labor involved anywhere along the McRib’s Dickensian journey from hog to tray, and certainly no regional variety, except for the binary sort — Yes, the McRib is available/No, it is not — that McDonald’s uses to promote the product. And while it hasn’t replaced barbecue, it does make a mockery of it.

The fake rib bones, those porky railroad ties that give the McRib its name, are a big middle finger to American labor and ingenuity — and worse, they’re the logical result of all that hard work. They don’t need a pitmaster to make the meat tender, and they don’t need bones for the meat to fall off — they can make their tender meat slurry into the bones they didn’t need in the first place.

And unlike a Low Country barbecue shack, McDonalds has the means to circumvent — or disregard — supply and demand problems. Indeed, they behave much more like a risk-averse day trader, waiting to see a spread between an Exchange Traded Fund and its underlying assets — waiting for the ticker to offer up a quick risk-free dollar.

Witness to all this, Americans on both coasts tweet jokes about the sandwich, and reference that one episode of “The Simpsons,” and trade horror stories, or play the contrarian card and claim to love it; and meanwhile, somewhere in Ohio, a 45-year-old laid-off factory worker drops a $5 bill on the counter at his local McDonald’s and asks a young person wearing a clip-on tie for the McRib meal, “to stay.” The McRib is available nationwide until November 14th.