Read This Book About Nazis

Sebastian Haffner’s ‘Defying Hitler’

I am going to try to get you to read a book with “Hitler” in the title, so I guess I need to say to anyone who is stupid, or thinks I’m stupid, or both: I do not think that Donald Trump is Hitler, and I do not think that the swarm of factors that deposited Trump in the Oval Office is any less historically specific than the one that empowered Hitler. But I do marvel at the things the past can tell us about the present state, and also the human state, when we listen. Defying Hitler vibrates with the tension that, as history education scholar Sam Wineburg puts it, “underlies every encounter with the past: the tension between the familiar and the strange, between feelings of proximity and feelings of distance in relation to the people we seek to understand.” The book has a dumb title and an ugly cover with a font that, in low lighting, can make it appear to the casual observer that you’re reading a book called Deifying Hitler. Even so, you should read it.

Defying Hitler is a memoir written in 1939 by a non-Jewish German, Sebastian Haffner, after he fled to Britain. It is written with the heat and urgency you might expect of a man who has escaped the Third Reich and now must account to himself and to outsiders what has happened to his country and how. The dizzying interwar years, the incredible rise to power of the Nazis, and the final slide into suffocating totalitarianism are arranged and described precisely, with particular attention to the ways historical events are experienced by ordinary people, and how they imprint on an individual’s, as well as a nation’s, psyche. For all that is distant in it, the book evokes strong feelings of proximity. In his daily life as a young man in Weimar Germany, Haffner’s biggest concerns are so familiar as to seem cliché: undefined romantic relationships, career ambivalence, and tensions with a loving parent who “mistrusted a life that consisted of visiting cafes and scribbling at irregular hours,” and steers his son towards law school.

The book is Haffner’s attempt to tell “the history of Germany as part of my own private story,” but it was never completed. The manuscript was discovered in a desk drawer by his son, Oliver Pretzel, who brought it to posthumous publication in Germany in 2000. There, the book became a bestseller, successful, according to Pretzel, because it provides, “direct answers to two questions that Germans of my generation had been asking their parents since the war: ‘How were the Nazis possible?’ and ‘Why didn’t you stop them?’” The weight Haffner gives to his interior experience is an argument through style, suggesting that central to the Nazi’s moral poison is the dissolution of boundaries: the encroachment of the public sphere into inner lives, the subsuming of private individuals into the Moloch of the totalitarian state. Nazism is an occupying force of the self as much as of a region.

Haffner considers himself a man with “no strong political views.” Of himself and his closest friend he says, “at heart we were both aesthetes. . . my god was the god of Goethe and Mozart.” He maintains, even after it is no longer tenable, a kind of Romantic understanding of an inner, private self to be guarded at all costs from the public sphere. Later, after political writers are being censored and dragged off to concentration camps, he notes with acrid distaste this same tendency in the literary establishment (he is by this point writing book reviews for a Nazi paper): “so many recollections of childhood, family novels, books on the countryside, nature poems, so many delicate and tender little baubles were written in Germany in the years 1934–38. . . in all their quiet tenderness they were screaming at you, between the lines, ‘Don’t you see how timeless and intimate we are?’”

If Haffner’s tendency to detach himself from public life is suspect, the opposite tendency — “to merge with the crowd” — is far uglier. In his estimation, it springs from a kind of ineptitude for self-direction that results from living in a time and place cluttered with disruptive historical events. He writes, “A generation of young Germans had become accustomed to having the entire content of their lives delivered gratis, so to speak, by the public sphere, all the raw material for their deeper emotions, for love and hate, joy and sorrow, but also all their sensations and thrills — accompanied though they might be by poverty, hunger, death, chaos, and peril.” Those unable to “wean themselves from the cheap sports of war and revolution” are Nazis in the making.

It is uncanny to read Haffner’s descriptions of a racist demagogue’s rise to power. Hitler is vulgar and buffoonish, gaudy and unkempt and frothing, widely regarded as too stupid, too ridiculous, too extreme to be a real threat and so is consistently underestimated, accommodated, or ignored by his opponents. But it is deeply unsettling to consider how non-Nazi Germans failed to stop or mitigate a government that came to power with the support of less than half of the country. Haffner casts blame, first and foremost, on the “treacherous party leadership” of the opposition that fails to mount a fight. But his most cutting insights he saves for the mental attitudes adopted by many in order to cope, but which ultimately hold dissenting Germans in paralyzed submission.

Haffner broadly categorizes the responses of non-Nazi Germans into three types. The first one, the “one often favored by older people, was withdrawal into an illusion: preferably the illusion of superiority,”

Every day they tried to convince themselves and others that this could not continue for long, and maintained an attitude of amused criticism. They spared themselves the perception of the fiendishness of Nazism by concentrating on its childishness, and misrepresented their position of complete, powerless subjugation as that of superior, unconcerned onlookers. They found it both comforting and reassuring to be able to quote a new joke or a new article about the Nazis from the London Times…The worst came for them when the Nazi Party visibly consolidated itself and had its first successes: they had no weapons to cope with these. . .They formed the majority of the late converts to Nazism in the years from 1935 to 1938.”

The second type is embitterment —

masochistically surrendering oneself to hate, suffering, and unrelieved pessimism. . . to give up completely once and for all; to let the world go to the devil with a wan indifference bordering on compliance; to commit sullen, angry suicide.

Finally, there is the type Haffner says he himself had to resist:

You do not want to let yourself be morally corrupted by hate and suffering, you want to remain good-natured, peaceful, amiable, and “nice.” But how to avoid hate and suffering if you are daily bombarded with things that cause them? You must ignore everything, look away, block your ears, seal yourself off. That leads to a hardening through softness and finally also to a form of madness: the loss of a sense of reality.

Bless anyone who can read these descriptions today without recognizing at least some of these tendencies in themselves.

When the Reichstag elections of 1930 make the Nazis the second-largest party in the German parliament, everyone underestimates the damage that they can wreak, because no one can conceive of how far outside the bounds of civilized thought they will travel. Haffner recollects, “At best I smelled a warning whiff of what was about to confront me, but I did not have an intellectual system that would help me deal with it.” In 1932, when Haffner learns Hitler has become Reichschancellor, “For about a minute [my reaction] was completely correct: icy horror. . . Then I shook the sensation off, tried to smile, started to consider, and found many reasons for reassurance.” Haffner and his father “agreed [the Nazi government] had a good chance of doing a lot of damage, but not much chance of surviving very long.”

Haffner documents the accretion of changes and erasures to everyday reality — the signs in store windows, the chant of “Juda verrecke!” (Perish, Jew!) on a Spring day — even as he tries to erect walls around a private domain. He observes, “There was no angle from which I could attack the Nazis. Well then, at least I would not let them interfere with my personal life.” In that spirit of private defiance, he attends the Berlin Carnival in 1932. Outside the party, he hears a scuffle and inside spots a man clad in black whom he mistakes for a costumed reveler with a poor sense of humor. The man tells the group to disband, and Haffner asks if they really must. “‘You have permission to leave’ was the reply, and I flinched, so threateningly had it been said: slowly, icily, and maliciously. . . The man had literally snarled at me, baring both rows of teeth, an unusual grimace for a human being. . . I shuddered. I had seen the face of the SS.”

Even institutions, which at first seem insulated, can persist in “unreality” for only so long. In the Kammergicht, or administrative court, where Haffner apprentices as a law clerk, “There were brown SA uniforms on the streets, demonstrations, shouts of ‘Heil,’ but otherwise it was ‘business as usual’. . . Which was the true reality? The chancellor could daily utter the vilest abuse against the Jews; there was nonetheless still a Jewish Kammergerichtstrat (Kammergericht judge) and member of our senate who continued to give his astute and careful judgements, and those judgements had the full weight of law…even if the highest officeholder of the state daily called their author a ‘parasite,’ a ‘subhuman,’ or a ‘plague.’”

The final chapters before the book cuts out take place in late 1933. Haffner, who concedes to his father not to expatriate until he finishes his law school exams, finds himself “wearing jackboots and a uniform with a swastika armband, and [spending] many hours marching in a column in the vicinity of Jüterbog.” There is little use of the first-person ‘I’ in this section, his individuality is lost to the cheap pleasures of camaraderie, his inner self hollowed out beneath his uniform. The writing becomes depersonalized, even dissociative: “one had a feeling that one participated mechanically, had no real existence or validity. . . I stood to attention and cleaned my rifle. But that did not count; I had not been asked before I did it; it was not me that did it; it was a game and I was acting a part.” We know he makes it out of Germany, but there is little to suggest that he does so with his soul intact.

The moral Haffner threads throughout the story is not the only reason the book is worth reading (The writing is immersive! His insights are fascinating! It’s a pleasurable way to learn some history!). But it does demand consideration. In a climactic moment, Haffner is holed up in the courthouse library, nose in a book, trying to tune out another “vulgar march” when the SA suddenly enter the building to arrest Jewish lawyers and judges. One lingers at Haffner’s table and asks if he is Jewish. Reflexively, Haffner answers no, then burns with silent shame. Whatever private dignity or part of his soul he was trying to preserve by turning away from the public sphere is gone in an instant.

That on the eve of war, Haffner abandoned the project of his memoir in order to turn his attention towards “something less private and more directly political” (a guide for the English about how to win the war) may be overdetermined. But it is hard to avoid reading meaning into it. Haffner uses a deeply personal mode of expression to narrate a private kind of defiance, and he fails. Looking back, it is almost quaint that he believed the greatest thing at stake was the soul.

Stolen Seats

Joe Biden helps Merrick Garland get even.

Judge Merrick Garland walked into his living room, where his wife was sitting quietly on the couch. The television was on. Jeopardy had just ended. The Garlands liked to watch together but that night Merrick was sidetracked, assisting the child of a former clerk with her law school admissions statement via Skype.

“It’s going to be Gorsuch,” Merrick said, gesturing to the television. Earlier that day he read that the President would be revealing his nominee for the Supreme Court, game-show style, and in primetime.

“Jeopardy just ended. Don’t pay attention to it. I’m not,” his wife said.

“I mean, our resumes are the same. I suppose he has a PhD. But I’ve been a judge longer. And my Circuit is better. And more of my former clerks have gone on to become law professors.” Merrick sat down next to his wife and put his head onto her lap. “He is a decade younger than I am.”

“And taller. Nina Totenberg says he likes fly fishing.” Merrick Garland’s wife began solving the New York Times crossword puzzle on her phone and waiting for her husband to go away.

“Of course. He’s conservative.” Merrick Garland got up from the couch. “So that means he’s rugged.” He made a fist and punched it into the air, pronouncing the word “rugged” like a pirate. “Give me a break. Everything he knows about fly fishing is from reading A River Runs Through It. His hands are as soft as these.” Merrick Garland held his hands up to his wife’s face. She slapped them away, gently.

“Judge Gorsuch. You’re such a dick,” he sang. “You’ll dismantle the EPA and make us all sick.”

“I don’t know. Call Joe Biden,” his wife offered. “Last time you were like this he knew how to cheer you up.” It was true. Being around an alpha male, someone who did whatever the hell he wanted at all times had helped Merrick Garland last time.

Merrick Garland dialed Joe Biden but no answer. He texted him, “hey.” Joe Biden responded immediately, “hey champ.”

“Oh hey. I just tried calling you,” Merrick typed. “But your phone is in your hand, seems like? Maybe you accidentally sent to voicemail.”

“Hi mom,” Joe Biden texted.

“Can you call me?”

Joe Biden called Merrick Garland.

“Want to come over and watch Season 1 of the Sopranos?” Merrick Garland asked.

“That sounds fun, pal, but I don’t think I’m in D.C. anymore,” Joe Biden answered. “Jill, where are we?” he yelled to his wife who couldn’t hear because she was doing cancer research in her study. “Jill? Dr. Biden, where are we?”

“Philly,” Jill Biden screamed loudly enough that Merrick Garland could hear on his end.

“I’m just not taking this Gorsuch nomination well,” Merrick explained. “Like, we’re so similar on paper.”

“Judge Gorsuch is a real man’s man though.”

“See, that’s what I mean. He’s an elite just as much as I am. The sportsman stuff, it’s all affect.”

“Merrick, what the hell are you saying? Donald Trump is the p-word and you’re whining about affect versus effect.”

“That’s not what — ” He took a deep breath and recited a mantra softly to himself. “Last time, when I was this upset, when Senator McConnell refused to interview me — ”

“I’ll take the Amtrak down tomorrow. Meet me in front of the Senate and dress up like we’re robbing a bank.”

Merrick Garland and Joe Biden met in front of the Senate as planned. Both were wearing black sweatsuits but neither appeared very threatening.

“Merrick, what’s the first thing you do when you start writing a judicial opinion?” Joe Biden asked.

“I make my margins one inch and tell the computer not to add space between paragraph breaks.”

Joe Biden mock punched the judge. “And after that?”

“I apply the facts of the case to the law.”

“Exactly right. You apply the facts of the case to the rule. And the rule here is: no stolen seats. And the fact is they’re Goddamn stealing the seat. They stole the seat from us. So what does that mean?”

Merrick Garland shrugged because he had no idea where Joe Biden was going and wished they could instead be watching the episode of the Sopranos where Tony and Meadow visit college.

“It means we steal all the seats from all the Senate toilets.”

“That’s not applying the facts to the rule?”

“All. Of. Them.” He loud whispered, while yanking Judge Garland into the bushes. Senator McCain, on his way to decide if today was the day he’d save the post-World War II order, didn’t see them.

“Ladies first.” Joe Biden said. He and Merrick Garland snuck into the women’s bathroom where Senator Claire McCaskill was at the sink wiping tears from her eyes. They pivoted quickly into the open stall behind her and Joe Biden began unscrewing the first toilet seat. He handed the screwdriver to Merrick Garland and with his eyes asked if he wanted to do the next one.

“I just feel if we keep saying ‘President Bannon’ eventually it will stick,” said a voice. It was Senator Amy Klobuchar.

“Yeah, but do his voters even care what we say?” asked Senator Kamala Harris. “I mean, you tell me. I’m from California.”

“Oh Claire,” Senator Klobuchar rushed over to Senator McCaskill. “What now?”

“I’m going to get primaried if I vote to confirm Judge Gorsuch.”

“Then don’t confirm him,” Senator Klobuchar said very reasonably.

“But we have to save the filibuster for when one of the liberals dies.”

Joe Biden coughed on purpose. There was only so much women’s crying he could take before he believed he ought to intervene.

“Joe, get the hell out of here,” Senator Klobuchar said without even having to look that it was Joe Biden hiding in a bathroom stall.

“Don’t mind us. We’re removing all the toilet seats in the Senate.”

“Stealing them. To protest my stolen seat,” Merrick Garland said.

“Neil Gorsuch is a real outdoorsman, my staffer told me,” Senator Harris said.

“You know, he wrote part of the Hobby Lobby decision,” Merrick Garland said.

“Of course we know that, Merrick. Do you know how many times I’ve been on the same Supreme Court Justice shortlist as you?” Senator Klobuchar asked as she took the toilet seat back from Joe Biden.

“No, no, let them continue. The resistance will take all forms. It’s good they’re doing this.” Senator McCaskill said as Senator Harris started making fundraising calls from the quiet stall nearest the window.

“Holy shit, did something die in here? Who’s in there?” Joe Biden kicked under the stall in the men’s bathroom.

“Is that Vice President Biden I hear out there? It’s Chuck Schumer.”

“Chuck, did something crawl up you and die?” Joe Biden asked, as Merrick Garland gagged into his black hoodie. “I hope Steve Bannon crawled up into you and died.”

“Ah yes, Joe,” Senator Schumer said as he emerged from his stall. “I too wish that.” He shook Merrick Garland’s hand. “Senator Klobuchar texted me that you two were doing this. I think it’s a great idea. Democrats need to start playing more three-dimensionally.”

“So do you think you’ll interview Neil Gorsuch?” Merrick Garland asked Senator Schumer.

“The skiing judge. You know, I read he was on the slopes when he found out his old boss, Justice Scalia, had passed.”

“That’s put on,” Merrick said. “And he clerked for Justice Kennedy not Justice Scalia.”

“Merrick, what the hell are you ever talking about? Eyes on the prize, kid,” Joe Biden yelled. “We’re pulling a stunt here. Not explaining.”

“Merrick, you leave the thinking to us now. Go enjoy your retirement,” Senator Schumer said as he washed and dried his hands.

“I’m still a judge on the D.C. Circuit,” Merrick said.

“Go have fun with Joe, now. It’ll all be fine,” Senator Schumer lied.

Joe Biden and Merrick Garland stood in the hallway, roadmapping which bathrooms to hit next, when Judge Gorsuch approached them.

“Oh my God. That’s him? He is a fucking cake eater,” Joe Biden said.

“He wants to gut the Chevron doctrine and help topple the administrative state. He wants to curb individual liberties unless you believe you are free to tell women when to use birth control.”

Joe Biden was not listening. He was walking towards Judge Gorsuch. “My God, he should be an athlete not a judge. Look at the size of those hands. He should’ve played hockey. I could’ve taught him how to body check. He could really check, that fucker, if he were a hockey player.”

“But the Supreme Court does check the President,” Merrick Garland said as he jogged to catch up with Joe Biden.

“No, like this.” Joe Biden checked Merrick Garland, playfully, but it was enough to knock over the appellate judge.

“Neil Gorsuch the fly fisherman.” Joe Biden extended his hand to the judge. “Why in the world didn’t you become a hockey player? My God, we could’ve transformed you into fucking tractor.”

“Vice President Biden.” He shook Joe Biden’s hand. “I would’ve loved to play professional hockey.”

“And Merrick Garland. A pleasure. Sorry I am sopping wet.” He gestured to his wet clothing and the trail of water behind him.

“We’re just pulling some pranks, Neil. Sorry about all that,” Merrick said.

“We just wanted a strong visual for our base,” Joe Biden continued.

“We’re sorry,” Merrick offered obsequiously.

“God damn it, Merrick. Don’t apologize for being right.” Joe yelled. “They stole your seat so we stole his.”

A Poem by Sally Ball

Armistice Day, France, 2015

Now comes the moment before darkness

when the river is the sky’s purple mirror

and the riverbank goes dark, the bridge goes dark, everything

melts into nothing save the light that faces itself.

As if it had come to an understanding, as if

it were listening to logic —

then very soon,

there’s nothing to see.

Sally Ball is the author of Wreck Me and Annus Mirabilis, both from Barrow Street. She’s an associate director of Four Way Books and teaches at Arizona State University.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Nebraska, "Pintxos"

What kind of curse is this?

You know the ancient curse Hittite curse that goes, “May you live forever, but only in the sense that each day seems like it will never end and each night goes on and on because you are sick with worry and unable to sleep through it, and the terror you feel is actually fully justified instead of being the usual generalized anxiety that comes with human consciousness, and you grow fearful of hearing news from the world because you know it can only be bad, and when you finally stop to breathe and reflect you realize that this horrible period of unbearable dread that seems as if it has been part of your life for so long hasn’t even been happening for two full weeks yet, how fucking crazy is that?” It always struck me as oddly specific and strange, but now it makes a lot more sense. They were a remarkably wise people, the Hittites. Too bad they were [checks Wikipedia] vanquished by the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BC.

Anyway, back here in our cursed existence there is still at least music to be had. This one gets a little jazzy in the middle but some people — cultured people — like that. I feel like those of you who don’t should learn how to appreciate it in the brief time we’ve got left. You don’t want to go to your grave as a philistine, right? And I don’t mean the [checks Google] non-Semitic people of ancient southern Palestine, who fought the Israelites in the 11th century BC. I mean it in the modern sense of the word. You know what I’m talking about. Anyway, enjoy.

New York City, January 31, 2017

★★★★ The pipes outside the practice-room window were gray; the white-brick building a block away was gray; the brownish bricks were grayish brown. Snowflakes, big and opaque, began going by, chiefly at a 45-degree angle but with various alternative speeds and directions mixed in. All through the morning and midday the flakes kept falling, sometimes cartoonishly large, sometimes tiny. They traced tree branches and stuck to parked cars and got in the grille scoops of cars that were moving. The flakes passed huge and individual through the field of vision while walking and hung dark against the sky above. One sailed into the mouth and melted there, keeping its texture for a fraction of a second. The snow kept changing and falling, then faded out a while before the daylight did. Out on the wet pavement at dusk, it was hard to decide whether the failure to accumulate had been mercy or insincerity.

This Twitter Account Definitely Didn't Predict Beyonce's Pregnancy

But isn’t it pretty to think so?

This afternoon, Beyonce announced that she’s expecting twins with husband Jay Z via an Instagram post. The world being… a bucket of sludge otherwise, people on Twitter are rightfully clinging to the good news as though it might be an omen. Things can still bring us joy! Look! Proof! And this announcement brings with it a few time-honored celebrity implications: these fetuses will most likely grow into babies that will be born and have names, which means there’s at least three good newses to look forward to on top of this one good news we’ve already got (born news, name news, photo-reveal news). At a time when we’re all frantically waiting for signs that our country’s pulse might regulate, here’s a familiar rhythm from our entertainment industry. Favorite singer and newly forgiven mogul husband double down on marriage with new pregnancy. Relief. Our show is still on.

Which brings me to this: @beyoncefan666. It’s an anonymous Twitter run by someone who appears to have correctly foretold of this whole pregnancy announcement back in July.

Okay so Beyoncé is gonna announce a pregnancy in February(2017)

The account was created in June and is full of predictions that might be explained away as guesses—they “knew” when Lady Gaga would release her next album, and who would win in the presidential election. It’s completely probable that this person tweeted out a ton of guesses while the account had no followers, deleted the ones that didn’t turn out to be true, and then RTed a tweet that happened to be correct from some more public account. But the specificity of “February(2017)” piqued my interest. I was hearing… my own rhythm. The scam rhythm. The “do I like this viral phenomenon?” rhythm.

The tweeter suggests they are an intern at Parkwood Entertainment (Beyonce’s entertainment/management company) and are “low key psychic,” two things some of the best content can be born out of. Underpaid teens bored out of their minds who suspect they may be undiscovered and special are why we keep the internet open for business at all. So one of them running this account sounds plausible. Likely? Maybe not. But still… not unlikely.

And so here I am, dredging through an anonymous account’s follows for signs of who could be behind it. Checking each tweet’s favs and RTs to see if I can spot any patterns. It doesn’t matter what I find, or if I even come to a personal conclusion about the account’s validity at all. The mere fact that I’m looking into it can be enough this afternoon. Our compulsions, ourselves. Thank you, @beyoncefan666.

The Great Escape

What does it mean to want to get away, existentially?

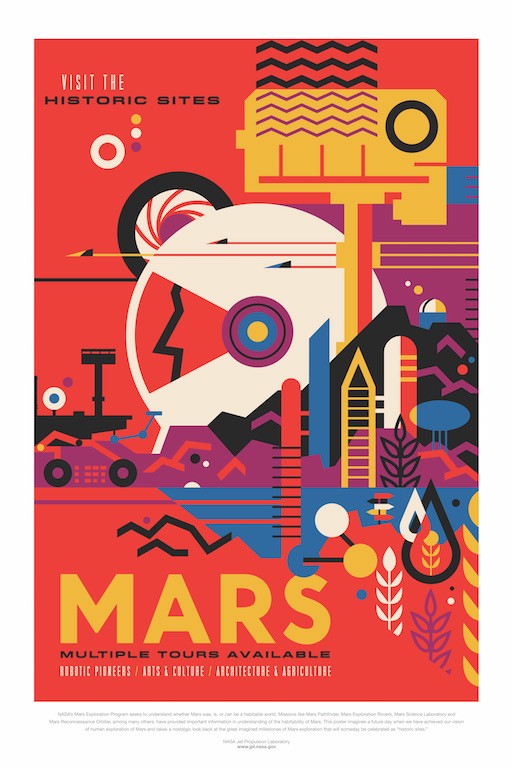

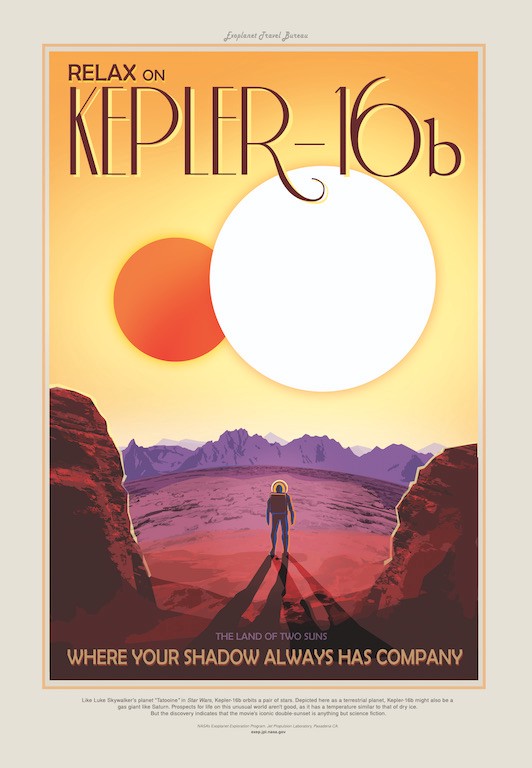

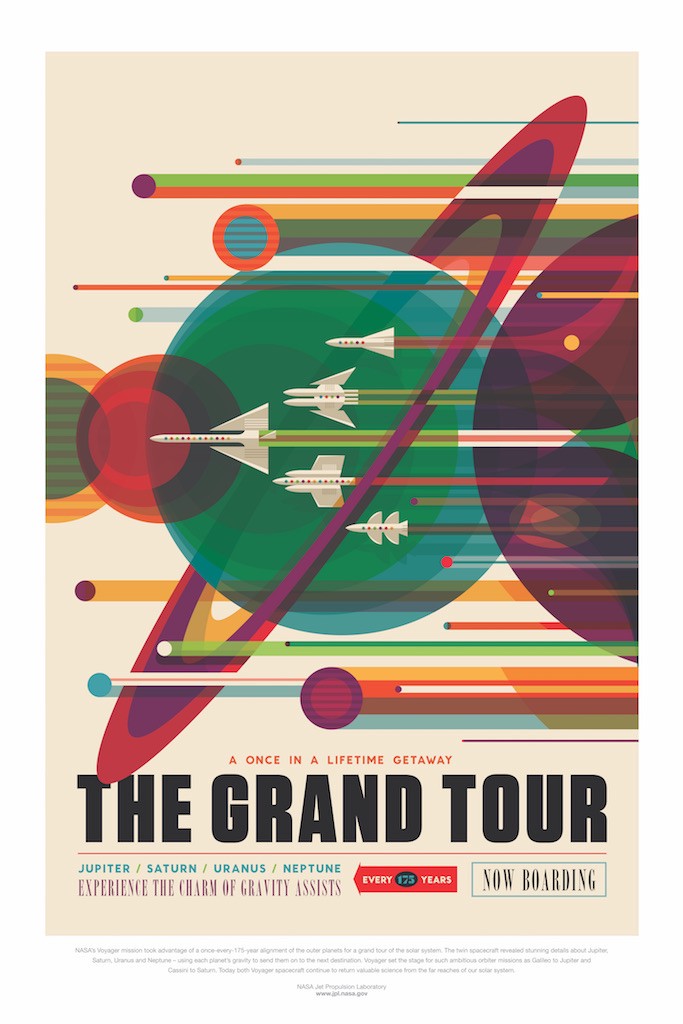

Afew years ago, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory made up a series of vintage-seeming posters advertising travel adventures to far away planets, much the way shipping companies in the ’30s did for cities in the South of France. The posters were a joke — kinda sorta — intended only for display online and in the Kennedy Center, where they might coincidentally, not-so-subliminally influence the dreams of young SpaceCamp-ers on vacation in Orlando. But, even now, with various Bond-villain-level billionaires tilting their private fortunes quixotically toward Mars, as Science Fictional as these posters may still in reality be, they’re a pretty good sign that we’ve reached peak escapism. Clearly, cabin porn just doesn’t do it any more.

This is not some manifest destiny fantasy of frontier living and Westerly Edens so much as a fantasy of flight from all that is known. Surely it is understandable to want to bury one’s head in the red sand of Mars, or perfect white beach of a supermodel’s Instagram post, rather than contemplate yet another mass shooting, an impending mass extinction, a Trump presidency, the coming Monday. It may be our earliest instinct. As children we run away, run and hide, hide and seek. As adolescents we might learn of our reptilian fight-or-flight impulse — we may even try it out, in a schoolyard or on a Eurail pass, depending. As adults, though, we get away, as in “plan the perfect getaway.”

The great irony of this sort of escapism—the Corona commercial as koan unto enlightenment — is that our yearning to travel is, at least in part, merely the result of the advertising and consumerism from which we are hoping to flee.

As the English journalist and filmmaker Adam Curtis said, in a recent profile on the occasion of his new BBC documentary, HyperNormalization,

The utopia they hold out is a world where machines make everything for you and you have endless leisure time, you become creative and everyone’s happy. And the only thing is, actually, everyone’s incredibly unhappy because they haven’t got anything to do. What we call our jobs today are actually fake jobs. We sit in our offices in front of our screens in order to get the money to go out and buy stuff. Our job is really to go shopping. And the rest of the time, we sit in our offices doing complicated managerial things, and when we’re not, we’re actually watching the internet. The internet is there to keep you happy during your fake job.

All of our escapes, then, online and IRL, real or illusory, are but temporary reprieves. We are the cosmopolitan citizens Andre Gregory posits in My Dinner With Andre who are always talking about an escape, who fixate on fleeing from the city, but never do, who have constructed their own prison, “and so they exist in a state of schizophrenia where they are both guards and prisoners.” We have knowingly built ourselves into the Matrix, you might say, and find ourselves to be in thrall with the décor. And, yet, as Gregory says to Wallace Shawn,

We’re bored now. We’re all bored. But has it ever occurred to you, Wally, that the process which creates this boredom that we see in the world now may very well be a self-perpetuating unconscious form of brainwashing created by a world totalitarian government based on money? And that all of this is much more dangerous, really, than one thinks? And that it’s not just a question of individual survival, Wally, but that somebody who’s bored is asleep? And somebody who’s asleep will not say no?

In the beginning, of course, there were no fake jobs, no prisoners of the hypercapitalist state. There were no escapist fantasies, no boundaries to transcend, no words even to express a wish to do so. And then — when did we start naming things? Genesis?—as recently as the Victorian era, some explorers still saw plenty of so-called blank spots on the map needing to be filled in, to be known and named. Now we have satellite systems mapping the edges of the universe and therapists to do the same for the interior of our psyches. And was that not the goal, to know ourselves? Wasn’t the idea that, if only we acquired enough self-awareness — a real and complete understanding of our nature, of our appetites and behavior — if we named our true selves, and acquired the material goods to go along with them, we might find our bliss?

Or is it that, having labeled ourselves with incredible care and Amazon-algorithm specificity (“I’m an Angeleno, a lefty, a writer, a Levi’s guy, a negroni guy, an-iPhone-NPR-Netflix-Nike-Nespresso-guy”), we feel trapped? Maybe then our desperation for quiet remove is really a physical metaphor for wanting to undo, or at least wind back, the naming of our selves, to be less confined by self-awareness, self-knowledge, even selfhood itself. Maybe, then, those Martian posters and the ads for beachside beers aren’t really selling a destination but a journey over the horizon, to where we can become unbound, undetermined, where we can return to a state of potential. Maybe what we fantasize about is forgetting ourselves — as in, “You forget yourself, Brutus,” as Cassius says. “Urge me no more or I shall forget myself.”

“We are never as good as we should be,” writes the British essayist and psychotherapist Adam Phillips, “and neither, it seems, are other people.” But still we flatter ourselves for our ability to tell the difference, between we and they, good and bad, as Phillips writes. “What are we, after all, but our powers of discrimination, our taste, the violence of our preferences?” Though, how articulate can we be in expressing ourselves, when our choices are only to ‘like’ or not, CNN or Fox, plastic or paper, coffee or tea, Tupac or Biggie? If we are all using the same media to tell our own stories, and the settings and the filters by which we separate ourselves limited, how individual can we show ourselves to be? And do we even need to?

Apart from just doing something, anything, to entertain ourselves in our fake jobs, to what end is this differentiation by drop-down menu, this multiple-choice-me, other than the commodification of our selves — as entrepreneurs of the ego, streamlining idiosyncrasy and contouring consistency, in the effort to market our avatars within a marketplace? Our identities, we are now told, depend on our selections within the consumer marketplace, our brand affiliations. We are what we buy. Even when we think ourselves too bold (“Obey Your Thirst”), too instinctive (“Just Do It”), idiosyncratic (“Think Different”), or adventurous (“Go Forth”) to be marketed to — our rebellion is sold with a label.

In this pursuit of our true, perfect, singular selves — and perhaps because of that pursuit — we can’t help but fall short. Which is not to suggest some sort of grand, existential failure. Rather, in place of Camus’s august failure to find meaning within an indifferent universe, our new absurd is merely a failure to reach fulfillment in the marketplace — commercial, romantic, or otherwise. Scrolling, swiping, searching — Sisyphus is now just twirling the spinny wheel of an ever-buffering timeline.

But if our goals, our expectations for ourselves, even, are always, perpetually, inevitably just out of reach, constantly over the horizon of the present, just on the other side of this screen, on the other side of this job, this workout, this purchase — on the other side of this anxious never-now where even the most recent posts, accomplishments and resolutions are time-stamped, dated, and decaying as soon as they arrive, D.O.A. — in that case, ought we not call those “goals” what they really are: oases? And then what is this web, this marketplace, this culture, but a trap?

Even among the rather contradictory characters in the Greek pantheon, the sea dwelling Proteus, shepherd of the seals, was a sort of slippery figure. According to Homer, who called him “Old Man of the Sea,” Proteus knew literally everything and so was, as you might expect, constantly the subject of seekers in need of guidance — a prophet to foretell their destiny. When captured, though, Proteus would try to escape by assuming various shapes, and only if his captor’s grip was true, would he then reveal to them their secrets.

Jung read Proteus as symbol of the unconscious, of course, whence comes every prophetic impulse, every creative idea, every real desire. But I’m here for the squelchy, muddy metaphorical man of myth slipping through everyone’s fingers. I’d like a mascot for existential potential, ontological dilettantism, if you will, patron saint of the hobbyist, the essayist, as in to essay through life, meandering through the arcades, trying on different modes, different ways of being as one might a shirt, checking for fit.

Maybe the wisdom that Proteus and the other shapeshifters of mythology have to share with us is their very mutability itself. Think of a single being able and allowed to assume all the various incarnations he might otherwise restrain, criticize, limit from being — Shakespeare able to inhabit Cassius and Brutus, as well as Hamlet and everyone else.

Borges, in an essay called From Someone to Nobody, uses Shakespeare specifically to illustrate the point:

…in 1774, Maurice Morgann states that King Lear and Falstaff are nothing but modifications of the mind of their inventor; at the beginning of the nineteenth century that opinion is recreated by Coleridge, for whom Shakespeare is no longer a man but a literary variation of the infinite God of Spinoza. Shakespeare as an individual person, he wrote, was a natura naturata, an effect, but “the universal which is potentially in each particular opened out to him . . . not as an abstraction of observation from a variety of men, but as the substance capable of endless modifications, of which his own personal existence was but one.” Hazlitt corroborated or confirmed this: “He was just like any other man, but that he was unlike other men. He was nothing in himself, but he was all that others were, or that could become.” Later, Hugo compared him to the ocean, which is the seedbed of all possible forms.

…and also home to Proteus. (Though, today, Hugo might instead look upward for his metaphor, comparing Shakespeare with the vastness of space, actual stellar nursery of the cosmos.)

In more modern times, Borges, author of “The Garden of Forking Paths,” conceiver of infinite libraries, of alternate realities, and of “The Aleph,” the story of a single point in space that contains all else, all that is even possible, was the best chronicler of the cosmic potentialities of the psyche, the quantum probabilities of the self. His stories, and the protean imagination whence they came, containing not only all of Shakespeare, but all of Quixote, are often described as anticipating the internet — the world wide web of people, ideas, identities.

And in our present wiki-reality, we have all become Borges characters, scholars of our infinite potential, but trapped, like so many Funes-the-Memoriouses, cataloguing our experience in riveting, if somewhat pointless detail on our feeds. And still the thesis of Someone to Nobody, remains vivid: in the beginning, many gods become one — Someone, individuated, self-actualized with a beard and a son and everything — and, then, He vanishes into omniscient, omnipotent void, back into pure potential.

One sympathizes. After all, isn’t that the ultimate getaway — vanishing? To disappear suddenly and completely; to recede from view; dematerialize; to delete your account and become an ontological Aleph, undefined, indescribable, infinity and zero, to disintegrate. Like you would in, I dunno, a vacuum. Like you might in deep space.

Sleep It Off

Correlation ≠ causation

Iconic rich woman and sleep advocate Arianna Huffington published a blog post a few days ago about how the current regime would be going a whole lot better if only our president would get more sleep.

On face value: sure. Why not? We all need more sleep, there’s so much science about how it makes you healthier. Why not have “more sleep” be one of the many things you wish for someone in a position of power? But then you keep reading, and apparently sleep is the only reason this presidency’s been rocky.

A Modest Proposal: Mr. President, Get Some Sleep

Here’s her case. First of all, sleep is what put a snag in Bill Clinton’s presidency:

“Clinton was still celebrating the victory and loved staying up half the night to laugh and talk with old friends,” Gergen wrote. “The next morning, he would be up at the crack of dawn to hit the beach for an early run or perhaps a game of touch football.” … How big of an effect did this have on Clinton’s presidency? His first week was dominated by his clumsy handling of the gays-in-the-military issue, which earned him criticism from those on both sides of the aisle. And according to Gergen, this way of working “planted seeds that almost destroyed Clinton’s presidency.”

And actually, while we’re on the topic of the Clintons, sleep is what tanked Hillary’s campaign.

Hillary Clinton might make the same admission one day, given that it was on the same night that she refused to rest after having been diagnosed with walking pneumonia that she made one of her worst mistakes of the campaign — calling Trump supporters a “basket of deplorables.”

So given those two touchstones, it should come as no surprise that our president is generating far-reaching and exponentially worse crises in his first few days:

“You know, I’m not a big sleeper,” he said during a campaign rally in Illinois. “I like three hours, four hours. I toss, I turn, I beep-de-beep, I want to find out what’s going on.” … So in effect he told us he wasn’t going to be sleeping much, and he’s keeping that promise. But this is one of the many promises he should consider breaking.

And that goes for his team, too:

And perhaps the reason the aides “tend to adopt his mindset” is because they’re also forced to adopt his sleeping habits.

There is no mention of cultural systems like racism, xenophobia, or masculinity, which suggests that everything that’s going on—all of this bad behavior—might be stopped if everyone involved would only have the decency to get some Zzz’s. What a nice thought!

Odd Lots: Curious Objects Up At Auction

An invitation to Studio 54, a French brothel bed, and pussycat portraiture

Lot 1: You’re Invited … to Get Down

The scene: Late ’70s at the hottest nightclub in New York City, Studio 54. And it was a scene, recorded by photographer Richard P. Manning, whose collection of “uncensored” gelatin silver prints goes to auction in West Palm Beach, Florida, on February 4. The original Studio 54 opened in 1977 and closed in 1980, well known in that brief period for its decadent parties and garishly attired guests. So many disco-age celebs are pictured here, young and beautiful — Andy Warhol, Cher, Debbie Harry — as are several unnamed nudies in various states of debauchery (NSFW).

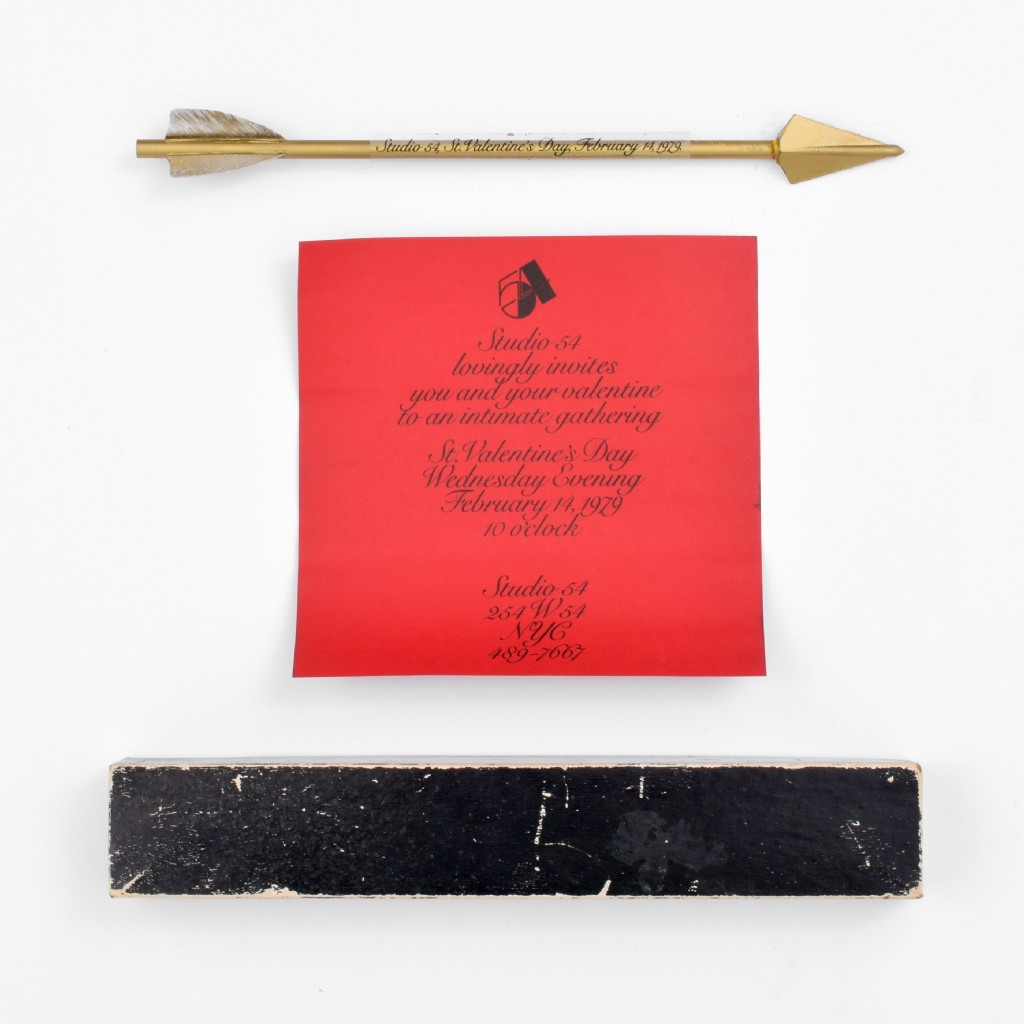

A less racy, but still evocative complement to Manning’s photographs is this red paper invitation to the 1979 Valentine’s Day soirée at Studio 54, bearing the iconic 54 logo, and accompanied by a golden cupid’s arrow. It can be mine — or yours — for about $1,500–2,500.

Lot 2: Le Lit of Ill Repute

To continue on the sensual theme — perhaps in honor of St. Valentine, patron of love — Sotheby’s London is hosting an entire auction devoted to the Erotic: Passion & Desire on February 16 (again, probably NSFW). Alongside a glass “fertility talisman,” explicit Man Ray photography, and, well, a painted plywood penis table supposedly crafted for Catherine II of Russia, a divine divan beckons.

This elaborately carved mahogany bed enjoys quite the reputation. According to the auctioneer, it “has traditionally been identified with the legendary Lit de la Païva, the love nest of the richest and most notorious demi-mondaine of the Second Empire.” La Païva, aka Esther Thérèse Lachmann (1819–1884), played mistress to kings and bankers, but this bed was never used at her infamous Hôtel. Instead, it landed in “the notorious brothel at 6 Rue des Moulins, near the Palais Royal, known by the deceptive name of ‘La Fleur Blanche,’” which housed numerous opulent bedrooms and a “popular torture chamber.” There are photographs documenting this mermaid-bedecked bed at Rue des Moulins, where it remained until 1946 when the contents of the establishment were dispersed at auction.

And here it is back on the auction block, where it can be had for something between $625,000 and $1 million.

Lot 3: Cat Art

This kitty cat oil on canvas is enigmatically signed “MM” and dated 1888, but otherwise little is known about it. The auctioneer, James D. Julia of Maine, describes it as “A remarkable 19th-century portrait of a precious family member, reminiscent of the portraits painted of children.” Which is true, it does have a New England folksy quality to it, and yet, does this feline not emanate scorn? He is bored, or tired, or disgusted with humans (who can blame him?), and he’s not here to cheer us up, goddammit; he’s the antithesis of LOLCats and Emergency Kittens. Still, quite lovable, and in need of a good home, if you have $3,000+ to spare on February 10.

Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places.

Remember New Jack Swing?

Soundscan Surprises, Week of 1/26

Back-catalog sales numbers of note from Nielsen SoundScan.

The definition of “back catalog” is: “at least 18 months old, have fallen below №100 on the Billboard 200 and do not have an active single on our radio.”

When was the last time you thought about Sheryl Crow? Me neither. The Grateful Dead’s eponymous debut record was released FIFTY YEARS AGO so there’s a 50th Anniversary reissue. Just another reminder that your hippie dad or dad-friend is officially OLD.

A three-part miniseries has been running on BET about New Edition, “The New Edition Story,” and the group may or may not be reuniting to record an album and go on tour. This is a good excuse to remind yourself of the style of music known as “new jack swing.” Thank you Teddy Riley; I’m off to make a Spotify playlist.

I guess one of 311’s records is turning 20 years old, so we who remember it are also officially very middle aged. John Mayer has a new whatever and he’s planning a world tour and I just don’t want to talk about how “into” his “music” I “was” as a “teen” and then try to defend my opinions by invoking his superior shredding skills because it’s all just very embarrassing for me so let’s just focus on how he’s definitely probably a slouchy creep. And whiny—don’t you imagine he’s moody and whiny? God. I’m sorry. I know.

I’m not sure what’s going on with Simon & Garfunkel except there’s that musical in England. Oh and Disturbed (yes, of Down With the Sickness) covered “The Sound of Silence.” Enjoy:

9. GRATEFUL DEAD GRATEFUL DEAD (50TH ANNIVERSAR 2,540 copies

10. SIMON & GARFUNKEL BEST OF SIMON & GARFUNKEL 2,431 copies

26. MAYER*JOHN CONTINUUM 1,890 copies

38. NEW EDITION HEART BREAK 1,624 copies

62. NEW EDITION ALL THE NUMBER ONES 1,366 copies

75. CROW*SHERYL VERY BEST OF SHERYL CROW 1,202 copies

142. NEW EDITION VOL. 1GREATEST HITS 909 copies

172. 311 TRANSISTOR 840 copies