New York City, February 8, 2017

★★ Bright blue came down through the blinds. Thin little purple clouds stretched out in the west. A child went out the door in a t-shirt, running to catch up to his friends in soccer shorts and socks. Downtown, an adult walked by in a t-shirt too, holding an iced coffee. Silvery haze and a smell like potting soil were on the damp and incomprehensibly warm air. Nothing added up right. In the dark, after the schools had already sent out the news they were closing for a snowstorm, children were tossing a light-up football, their jackets discarded in a heap on the low wall by the planters.

Meet Me In My Byre Dwelling

BYO livestock

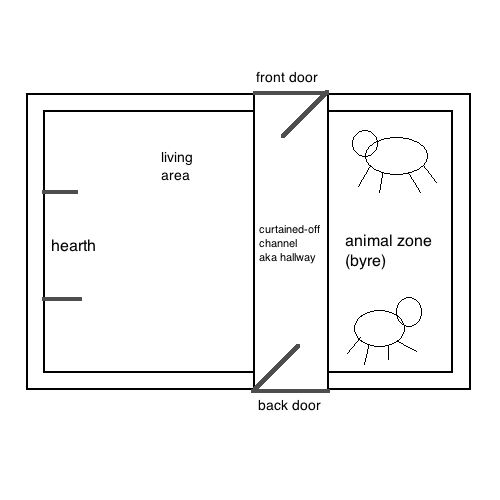

In northwestern Europe, from around the Bronze Age to the 1800s, it was very common for people’s houses to include an attached area for their larger livestock. Most civilians weren’t rich enough to have a team of cows, but let’s say your family had two cows, some sheep, and a couple chickens. Upper middle class! Without a herd to keep them warm, your livestock wouldn’t fare too well at night in the snow, so you’d allot a section of your house for barn activities and in turn, the animals would help your drafty rooms stay heated. This smelly, symbiotic environment was called a byre dwelling (or a barn house) and I for one am sold.

Byre Dwelling: An example from Co. Mayo of a family home occupied by both the family and their milking cows.

It applies all of the charm of hygge, but practically instead of commercially. Throw your fair isle turtleneck on the fire and get shearing, honey. Depending on your financial situation and how into design you were, there were a couple of ways to navigate the “my house is a barn” aesthetic. According to historians, many byre dwellings had a sunken groove down the center of the floor called a channel, so the cow excrement could slowly leak down the slope and out into the yard. During temperate times of the year, a family might put up a curtain to divide their space from the others, but on a snowy day like the one we’re having in New York, you’d probably opt for a more open floor plan so that everyone’s body heat could circulate.

The animals would hang out, tethered and calm, and while there doesn’t seem to be a fair use picture of a byre interior for me, here is my artist’s rendering:

Eventually the byre fell out of favor, though. Apparently some parts of Europe got too cool for roommates. “Colonial British commentators were generally horrified at the Irish tradition of living under the same roof as livestock,” historian Marion McGarry explains. “Citing it as yet more evidence that the Irish were savage and incapable of self-governance.” Rude. Isn’t it possible, instead, haters, that the peasants were just extremely good at cohabitating?

Eventually, exterior byres became the norm and “the former byres were partitioned with a wall, given a window and converted into a bedroom.” And just like that, our animals were relegated to the yard and we were relegated to multi-bedroom dwellings. It’s like watching granite countertops recede and marble countertops move in—only a matter of time until we run out of ideas and circle back around on this, right?

Culture On 'Culture'

The quick ascent of Migos, and the trajectory of trap.

The first two times I heard “Bad and Boujee” couldn’t have been more different. The former was literally in my mother’s car. We were stuck at a light, picking up groceries, and that’s when the keys struck the track and Offset started talking his shit and Young Metro’s seal of approval buzzed across the introduction.

I didn’t know what to think. It sounded like trap. The verses were grimy. But then there were the piano keys tinkling just behind the chorus. I’d seen the “raindrop, droptop” motif across all of my feeds, but I hadn’t known what it meant — so imagine my surprise to find my mother nodding along with Quavo’s second verse (and I didn’t know it at the time, but it was a gesture I’d find mirrored just about everywhere, over the next few months, until one I day I looked up from whatever I was doing to find myself doing it too).

The next time was back in Louisiana, across from my apartment, a few days had later. One of my neighbors, a nice guy (we’ll call him Tommy) works at a gas station, a gig he picked up once he’d stopped dealing drugs. We were standing outside, just sort of staring at the road, when the bass rang out from this car a few streets down and Tommy started shifting along with it, and then we were both out there, just sort of dancing. When the third verse hit, he nodded deeper, as if in agreement.

When I asked who it was, he cocked his head a little bit. He said it was the motherfucking Migos. He told me the track came off of Culture, and that the album would drop soon, and that it would be the number one album in America. I started to call bullshit, because that’s a pretty hefty assertion, and that’s when Tommy told me that the record wasn’t called just Culture, it was Culture. Tommy told me that when it dropped, I would see, everyone would see, we wouldn’t even know how it happened.

On January 8, Donald Glover shouted out Migos on the Golden Globes stage. He cited “Bad and Boujee” (“the best song ever”). Then, on January 27, Migos dropped Culture. On February 5, it became the number one album in the country.

Migos formed in 2009, by way of Lawrenceville, Georgia. Quavo, Takeoff, and Offset are the group’s three members. They are directly related (Takeoff is Quavo’s newphew; Offset and Quavo are cousins) and while there is no obvious leader or iconoclast, they’ve likened themselves to “Ed, Edd, and Eddy.” Prior to Culture, they dropped “Yung Rich Nation” in 2015 (which featured the preposterously catchy “Pipe it Up”), in addition to three other mixtapes (“No Label”, “No Label 2” and “Juug Season”). Their shows have gained a reputation for a certain brand of raucousness, a theme that can play in your favor until all of a sudden it doesn’t.

Nevertheless, they’re brilliant. They’re a bunch of talented musicians. And one of the keys to that brilliance is an ability to bring seemingly disparate strands on the musical spectrum together in under three minutes. Across “Big on Big,” one of Culture’s many standouts, when the group asks, “How you gon’ big on big,” it’s an assertion as much as a dare: can you really do better? Do you have what it takes to improve on the formula? You probably don’t.

A lot of the appeal can be understood through their “Bad and Boujee” video — they’re cooling out, eating ramen in what could very well be a Waffle House, but also possibly be a Denny’s, or a Deanie’s, or a Frank’s, or a Lola’s, or whatever ambiguous diner is taking up space in your imagination. The location isn’t the point, they seem to say, but also it very much is—they can stunt regardless of where they are.

When you’ve titled your record Culture, the question inevitably emerges of what that is, and who gets to claim it. It makes you wonder who gave them permission. It could be, as DJ Khaled notes on the record’s intro (“for all you fuckboys that ever doubted the Migos”) that “they rep the culture from the streets.” Or maybe the culture they’re packaging is exclusive. Or maybe the question, for all of its momentum, is moot.

Trap music, as an idea, started as one thing — utilizing the sparest assortment of beats on-hand to deliver the gruffest, hardest rhymes at an artist’s disposal — and through the phantasms of the music industry, it’s since become a similar other. The same permutations have occurred with what we’d have originally identified as screw, and dub-step, and dancehall, and other forms that’ve been molded away from their original variables by the market’s demands. But, in this way, the genre becomes akin to other hyper-specific forms (like reggaeton, or k-pop), and the trick becomes retaining the particularity, while capitalizing on the variables that draw so many folks in. In some respects, this notion takes away from the culture. In others, it allows it to spread. And then all of a sudden, you’re hearing Migos in the suburbs, or in the backrooms of your church groups.

There’s a Billy Collins poem (a guy whose craft many practitioners would argue is more demonstrative of culture) where he riffs on what attracts him to the music that really gets through to him:

The music is loud yet so confidential

I cannot help feeling even more

like the center of the universe

In Migos’s second long feature with the FADER (their first since releasing Culture’s singles) the group rounded out the discussion with nods to their predecessors. They touched on their genre’s empiricism, and Donald Glover, and ambition. In a country as polarized as ours, any medium that jumps from boundary to boundary is remarkable in its own right. It is only fitting — it only makes absolute sense — that that the record which most resonates with so many people today, is coming from the beats and stereos of a group of black men from the South.

In one of their more thoughtful interviews, with BigBoy TV, Migos was asked about the translatability of their music, and how much their group dynamic plays into it. TakeOff chalked success up to their malleability:

We always just understand each other… the only thing we care about is making shit that we care about, with each other. As of now, we’re pushing the gas. Whichever one goes up, whichever one goes harder, whichever one’s out there we support them to the fullest.

When the interviewer switches gears, to ask if anyone who hadn’t supported them has since jumped on the track, the group exchanges looks between them. There are murmurs of “yeah,” and “a lot of people,” before Quavo shakes his head.

“Yeah nigga,” he says, “the whole world.”

“But,” he adds, “You got to keep your arms open.”

And there are nods around the table when he finally says, “We know how to smile and coast.”

A few weeks back, apropos of everything, Migos hosted a class on culture at NYU. The talk was billed as an “intimate discussion.” Among other things, they touched on emotionality across their oeuvre, the symbolism of their record’s cover, and a bunch of anecdotes from their upbringing. Quavo talked about the time he was almost stolen at birth. The group talked about their hidden tear-jerkers, tracks that didn’t make it onto the record. The session was illuminating, and loose, and just about everything you could’ve hoped for. A few days before that, the group had allegedly smoked out Jimmy Kimmel’s green room.

Around the same time, many states away, I heard “T-Shirt” behind the counter of a corner store in the Tremé. The guy behind the register nodded along. He’s this Afgahni dude. He moved here a few years after Katrina. His father owns the shop, and every now and again the old man emerges from the butchery in the back to scowl. When I finished paying for everything, I asked my cashier what he thought of the track. He told me it was nice. He smiled wide when he said it. When I asked him why, he looked at me as if it were a stupid question, which, in many ways, it was. He told me it made him feel good. That was his final metric.

Perhaps that’s the Migos’s crowning achievement: their music makes you feel good. That they manage to do this across every track on Culture is as much of a miracle as anyone can reasonably expect. And few things have made me happier this year, or any year, than yelling “BROWN — PAPER — BAGS,” or “MAMA TOLD ME NOT TO SELL WORK,” or even “YEAH, THAT WAY, WE FROM THE NORTH YEAH THAT WAY,” when those tracks tells me it’s time to do that.

I don’t know what the working definition of culture is offhand, but if it excludes this album, I don’t want any part of it. It brings people together. It makes them feel good. That’s how culture should work.

How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Just Listen To Shostakovich's 'Symphony �-5'

Classical Music Hour with Fran

Every week, I am inundated with questions from every single person I know. Questions like, “Fran, did you ever write about classical music when you were in college?” or “Fran, what did you write your junior history thesis about — was it limited to Shostakovich or more all-encompassing of classical music under Stalin?” or “Fran, how did you, specifically, pull all-nighters in college in a way that was the least harmful to your academic career?” Enough! Enough, I say. Once and for all, I will finally write about my history junior thesis topic, which was Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony №5.

When I wrote about Shostakovich not all that long ago for this column, I picked one of his later and most palatable pieces: Festive Overture. Festive Overture is short and sweet and succinct and fun. It was Shostakovich post-Stalin, feeling a little lighter and more buoyant, musically. Symphony №5, however, couldn’t be further from that. But I am returning to the same London Symphony Orchestra recording from 2011.

To recap, generally, on what led to Shostakovich’s Symphony №5 being the tricky puzzle it would become: following the premiere of his opera, Lady Macbeth, Shostakovich was more or less blacklisted by the Russian propaganda newspaper Pravda. As Stalin and his rogue’s gallery picked off the composer’s main circle — either killing or disappearing those close to him — Shostakovich slowly withdrew from public society. Dude was scared to make art. I get it. I am constantly afraid to tweet something bad for fear all of my friends will, uh, mute me? I didn’t think this metaphor through enough.

So about a year later, Shostakovich returns to the scene with his Symphony №5 and it’s this huge, mind-blowing success. “Shosty’s back, baby,” reads Pravda (Pravda did not write that). But Shostakovich gets all of these high-ranking Communist officials back on his side. Stalin loves him again. And the symphony, widely regarded as a masterpiece, is good, but it also leaves everyone wondering: Did Shostakovich sell out? Is he Stalin’s little boy now? Or is this a deeply subversive piece of music that reflect its composer’s anguish and horror at what was happening around him?

I chose Symphony №5 because I also want to write about pieces that are difficult to listen to. I’ve focused heavily on pieces that are, well, genuinely just nice. Things to calm you, things to soothe you. Help you focus, help you breathe, whatever. That is not what Symphony №5 is. As you start its first movement, the Moderate — Allegro non troppo, it’s going to make you uneasy. The bold opening on the cellos is unsettling and frightening. It doesn’t really fall into a traditional sonata form. Its melodies are abstract, they come and go. But not all music is meant to comfort, not all art is compassionate. Symphony №5 is intended to be hero’s journey — perhaps Shostakovich’s himself — and it begins where he does, at a point of hesitation and fear.

From there, its second movement is actually an Allegretto, whereas most traditional symphonies have a Largo first, that begins with an upbeat melody on the cellos. Here’s where things start to get interesting. Rather than go from its uneasy first movement into a slow, thoughtful Largo — a narrative choice that would perhaps capture the tragedy of the Soviet empire — Symphony №5 gets kind of… funny? Tongue-in-cheek? It’s like the musical equivalent of saying, “Chill out, we’re all fine here,” while your eyes get real wide to signal you need help. It’s no less playful than your Saint-Saëns or your Beethoven, but it feels so much more twisted. There’s a melody right at the 0:52 mark that feels particularly conniving and unsettling, as if it was meant to represent Stalin’s manipulation of the arts scene itself.

As Symphony №5 slows down with its Largo, Shostakovich takes the time to present music that is complicated and difficult about grief and loss. This isn’t the type of rich melody we’re used to in Dvořák’s? Symphony From The New World. It goes back and forth between low, haunting melodies and sharp, stressful strings. It’s easy to lose your place in it, as I’d say is the case with actual grief. It’s cautious. It’s nervous. It’s not meant to soothe or pay tribute to something; it’s meant to sink in. When the theme from the first movement returns around the 8:31 mark, it doesn’t provide a sense of relief. It’s not an “oh, I know this,” it’s an “oh, it’s back.”

If you know anything from Symphony №5, you know its finale. The Allegro non troppo has a wildly famous introduction: high-pitched woodwinds lead into a furious timpani solo. This is one of the timpani parts I cherished the year I played it. Percussion is at the forefront of this movement, not merely there to support the sounds of the rest of the orchestra. At the time of this symphony’s premiere, it was viewed as a highly triumphant piece of work praising the Soviet empire; to me, it has always felt so angry and cathartic. The trumpet solo at the 2:30 mark is like a voice of reason crying out over a sea of strings. This is the equivalent of, I don’t know, pushing a bunch of papers off of a desk. Logging off of Twitter. So when the hopeful melody comes in right before the 3 minute mark, it feels somewhat disingenuous. A plastered-on smile that reads, “Everything is actually extremely fine.”

I don’t know, truly, if this is a big subversive piece of music. It soothes a lot of people to think that Shostakovich wrote this to go against Stalin, and sure, I’m not going to say he didn’t, but above all else: Symphony №5 has always felt like an honest piece of music. A piece of music about fear and anger and how great those two emotions can be. How majestic they are, and how music doesn’t owe you comfort. There’s no reason to comfort the masses. They don’t need it.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

He Met His First Real Heckler

The Adams family

“[T]hat was the beginning of who I am today. All of the humor and self-deflection I would ever learn came from that night. I am now grateful for it all. I know the nature of people. I know how they will throw insults and rock a boat just to watch a person go over the side. But I know they are not all cruel. Away from the stage lights, I would study others and look for that good. I became the person who would send an email every year to the genius writer of that song on his birthday, which is also mine. I would learn how to show empathy, or fight for myself, or make fun of it all, and shine some love on that lonely, crazy person we have all stood next to before, screaming into the night from the shadows. I toasted the last drink I ever drank to that heckler the day I cleaned up.”

Awl pal Ryan Adams tells all about “the ‘Summer of ‘69’ incident.”

Ryan Adams: The First Time I Was Rattled by a Heckler

Related:

Toto, We're Not In Dystopia Anymore

A 2013 videogame about border control brings the immigration ban to life.

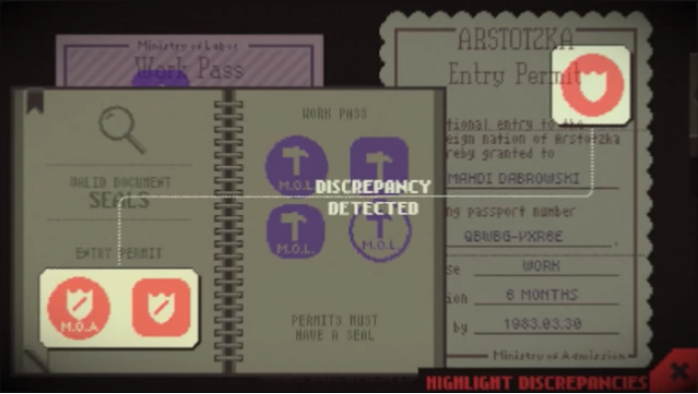

The interactive nature of Papers, Please gives players a window into how fascism manifests itself in bureaucracy. The brilliance of the game’s paperwork gameplay is that it makes the player complicit in the projection of state power. The player takes personal responsibility for the validity of each document that gets handed to them. If the player is wrong — if they forget to check a visa’s expiration date; or forget that the official MOA seal was changed from an X to a slash; or admit an immigrant with the wrong stamp on their work permit; or forget that Arstotzka, since this morning, has been in engaged in a dispute with neighboring Kolechia, whose various diplomatic seals are variations on an asterisk shape; or forget to check the most-wanted list — then they might be responsible for admitting a terrorist into the country. Each piece of paper that the player checks represents a tacit agreement with state policy. The flip side is that each layer of bureaucracy is an opportunity to resist.

Over at The Ringer, Jason Concepcion (whom I have trouble thinking of as anything but “netw-three-rk”) has an excellent diary about playing the indie game “Papers, Please” in Trump’s America. What was once probably an allegory about the threat of fascism is now depressingly realistic. You can play it here.

‘Papers, Please’ Is a Disturbing Video Game About Immigration

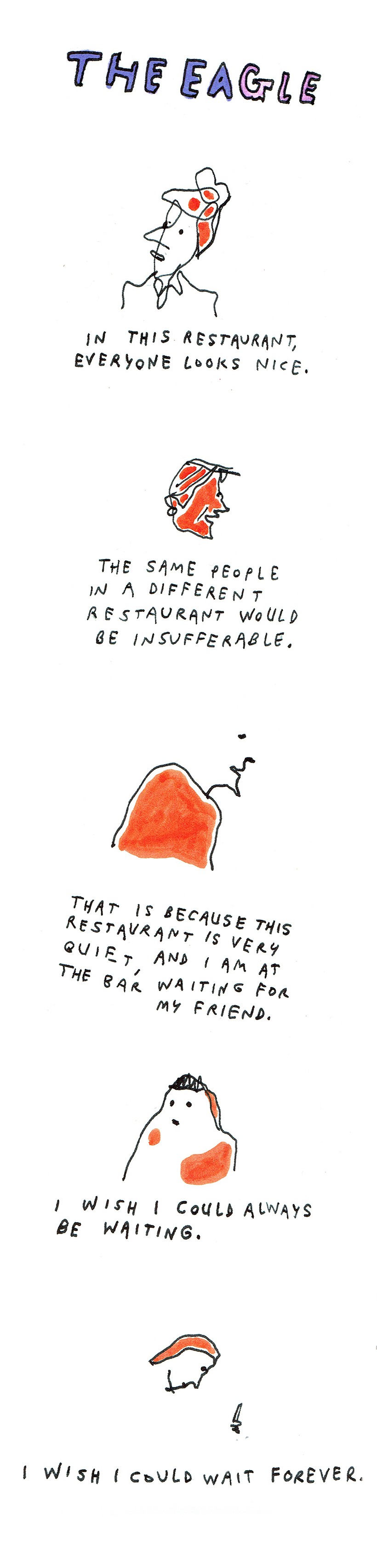

Restaurant Review

The Adventures of Liana Finck

Liana Finck’s cartoons are in The New Yorker and on Instagram. Her book is A Bintel Brief.

A Poem by John Wall Barger

PC Song

“The moon over Auschwitz”

was the original title

of this poem. I stared at it

so long I lost track

of what that moon

shone upon. I thought

I can’t write that,

I’m not Jewish,

I’ve never even been

to Poland! I did not mean

harm. Moon

can mean sorrow:

as in, I read how the dark

side of the moon

is actually turquoise

which glows like ice

over the barracks

of Birkenau. Oh!

I did it again.

Now you are googling me

to confirm that I am,

as you guessed,

a white dude. You doubt

that bad things

have happened to me.

I doubt it too. So many

bad poems are litanies of

personal trauma

peppered with trope,

one would think

stepping into daylight is enough

to terrify us all

but isn’t it? How different

is the Auschwitz moon

from the moon over

Disneyland? Each drifts over us

like a clod washed away

by the sea. I did walk

the Villa Medici in moonglow

between goddess statues

which like clouds have no face

or is that La Dolce Vita,

or Zatoichi: Blind Swordsman?

Yes it’s Zatoichi

touching the lovely face of

the sister of a yakuza,

they are falling in love,

Zatoichi’s fingers

in the language of movies

are aspects of the moon.

Have you ever seen the moon

on a sunny afternoon

out of nowhere?

Like a watermark in the desert,

like an old man

I washed dishes with

who kept taking breaks

to play harmonica.

When you’re drowsy

or stoned, when you’re really

not looking —

then the moon comes,

its kidskin grin,

the Padre Pio cuts

in each of its palms,

while far below

down here

fire rises upwards

water flows downwards

love spirals

outwards

& hour after hour

we carry our dead out of its light

like ants.

John Wall Barger’s poems have appeared in The Cincinnati Review, Rattle, Subtropics, Cimarron Review, the Montreal Prize Global Poetry Anthology and The Best Canadian Poetry. His third collection, The Book of Festus (2015, Palimpsest), was nominated for the 2016 JM Abraham Poetry Award.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Lowly, "Mornings"

Remember when snow days were something to be excited about?

I stayed up way too late last night reading a book because my mind said, “Snow day! You don’t need to get up early!” It was only this morning that my alarm clock reminded my mind and me that we are not in high school anymore, and we weren’t exactly so happy about life then either, why would we somehow keep ourselves stuck in that era? My mind is the dumbest thing I know. Anyway I’m exhausted now and the beauty and majesty of the forces of nature, while admittedly impressive, are not doing a whole lot to improve my mood. This track from Lowly helps a little, though. Enjoy.

New York City, February 7, 2017

★★ The fog didn’t really hide the river, but it made the landscape continuously gray with the sky. The early rain, thin but constant, was of a piece with the whole. The daylight was too depleted for judging the difference between a black shirt and a navy one unless they were held up against one another. A full downpour lasted not quite long enough to interfere with going to lunch, then departed, leaving not a true change of situation but ongoing intermittent rain.