The Astounding Wrongness of Bill Keller on Hate Crimes

Apparently the only person who can convince me of the legal and moral sense of hate crimes laws is Times columnist Bill Keller, because his case against them is so terribly bad. Keller has tardily joined the ranks of liberals so opposed, including Andrew Sullivan, the Quakers and also noted legal theorist Bill Maher. (He’s also found himself in the fine company of the Georgia State Supreme Court.) But that he’s chosen to come out in the context of Travyon Martin and the Tyler Clementi case doesn’t even begin to make sense.

Of course it’d be really easy to go the “straight white millionaire who was born when there were only 48 states explains why hate crimes laws are bad” route on Bill Keller, but let’s just note that unfair impulse and set it aside.

It’s much easier to pick on him for using “two makes a trend” — particularly when one case is the Trayvon Martin case, which actually isn’t a case, since no one’s been charged of anything, and the other is the Tyler Clementi case. Lots of people — myself included — have already noted their unease with the application of hate crime charges in the Case of the Obnoxious and Bullying Roommate, in the events that took place prior to Clementi’s suicide. The particular charge in this case that concerns Keller is “bias intimidation.” But Keller clearly misunderstands what happened, and what the jury said.

In New Jersey, that bias intimidation charge means that “a person is guilty of the crime of bias intimidation if he commits, attempts to commit, conspires with another to commit, or threatens” a crime “with a purpose to intimidate an individual or group of individuals because of race, color, religion, gender, handicap, sexual orientation, or ethnicity.”

Dharun Ravi, Clementi’s roommate, was found guilty of this once — and, you know, also guilty of lots of other charges, including invasion of privacy, destroying evidence, “hindering apprehension or prosecution” and good old witness tampering. (Seven of those counts, in fact, were about witness tampering and hindering apprehension.)

But on the vast array of bias charges, he was acquitted.

Perhaps Keller was confused because his paper covered this trial so poorly. “A former Rutgers University student was convicted on Friday on all 15 charges he had faced for using a webcam to spy on his roommate having sex with another man, a verdict poised to broaden the definition of hate crimes in an era when laws have not kept up with evolving technology” was how their trial conviction news story opened. But he was convicted on parts of all fifteen counts, and acquitted on bias charges on almost all of them.

And then here’s how Keller describes this jury: “My reading of the case is that the jury seized on those handy bias statutes in a clumsy attempt to punish somebody for a death that remains unexplained.” That’s not at all what happened, even with a glancing read; the jury clearly very carefully decided on which charges they would acquit and convict, and therefore rejected most of the bias claims. (And sentencing takes place in May, so we can’t bemoan Ravi’s prison sentence yet, because there isn’t one.)

With regard to Trayvon Martin, which, if it is established to be a crime, does seem somewhat likely to have bias charges involved. The victim — or at least the person who is dead — seems to have been chosen solely for being black. Meanwhile, it has taken a national outcry to get police to pursue the case. But… right. There are no charges. This is a made-up complaint about hate crimes laws, since no one has been charged with anything yet.

Putting aside what did or did not happen in Sanford, still, we do know that Trayvon was followed and reported to the police for being black and male while walking. So when Keller writes that the public outrage is “fashioning a narrative from the hate-crimes textbook — bellowing analogies to the racist nightmares of Birmingham and Selma” and that that is “just political opportunism,” he’s way into the realm of whitesplaining to a world who knows very well that black people are often treated differently by people with guns. While he’s criticizing “the media” here (in this case, talking head commentators), what’s “political” about your or my own outrage over this case? Not a thing. He’s held up a media strawman to represent us all, and it doesn’t work.

So why does Keller hang his anti-bias law arguments on these two cases? What makes Keller’s op-ed so unconvincing and off-the-mark is the 3116 individuals accused of committing assault and bias crime in 2010 alone, the most recent year for which FBI hate crime statistics are available. Using two cases — actually, just one case, and even then, one case in which nearly all the bias charges were thrown out — to weigh in against hate crimes laws is an enormous piece of negligence. To overlook actual cases of bias crime to denounce bias crime charges is nonsensical. I’m not even an enthusiast of hate crime laws, and even I think this is unfair.

In 2007, according to the FBI, there were 7624 bias crimes reported. Half of those were race-based; 15% were about sexual orientation. In 2010, there were 6,624 bias crimes reported, which included seven murders, and a slightly greater percentage of crimes against gay people — and those assumed to be gay.

And also, when people talk about hate crimes, they forget that about 40% of those events were crimes against property, not people. This is why, for one thing, the Church Arson Prevention Act of 1996 happened, but that’s just not as sexy to talk about.

But even just talking about bias crime against humans, Keller could have chosen nearly any of the seven murders in 2010. Like Keith Phoenix, who beat Jose Sucuzhanay to death with a baseball bat just because he assumed the victim’s brother was his gay lover. He, in fact, pulled his car over to literally beat a stranger to death. It was just another lethal year for straight people to be assumed to be gay. If cases like that aren’t indicative that people target people for crimes based on their identity, I don’t know what is.

Fast Food Is Depressing

Fast Food Is Depressing

“There is a direct relationship between eating fast food or commercial baked goods (doughnuts, cakes, croissants) and the risk of developing depression, according to a recent study by scientists from the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and the University of Granada. The findings reveal that consumers of fast food are 51 percent more likely to develop depression than minimal or non-consumers. Furthermore, the connection between the two is so strong that ‘the more fast food you consume, the greater the risk of depression,’ said Almudena Sánchez-Villegas, Ph.D., lead author of the study.”

— Additionally, fast-food consumers are lonely, vegetable-averse smokers who work a lot. Does this describe YOU OR SOMEONE YOU KNOW? Probably. Sad.

Photo by Ariwasabi, via Shutterstock

'Diner': A Look Back

Here’s a good oral history of one of the all-time great comedies in American cinema.

Talking Bear True Crime With Jessica Grose

Today Slate publishes “A Death in Yellowstone: On the trail of a killer grizzly bear,” an 8000-word investigation by Awl pal Jessica Grose about the search for “the Wapiti sow,” a 250-pound grizzly bear implicated in the killing of two separate visitors to Yellowstone National Park in 2011. The story is both about the hunt for the bear and the larger implications of man’s sometimes fatal interactions with nature. It’s a remarkably compelling report that you absolutely need to read. Here’s a brief conversation about the piece.

Jess Grose, I loved this report. But I am a confirmed bear aficionado. What drew you to the story?

My husband’s family has a place in rural Wyoming, about 40 minutes from the Northeast entrance to Yellowstone in Silver Gate, Montana. I went for the first time in August of 2011 — it’s remote and difficult to get to. I am not an earnest person in general, but the physical beauty of that part of the country really moved me on a visceral level. This was so surprising — I’ve always liked to hike and cross country ski but I’m not especially outdoorsy or nature loving. Before we got there, my mother-in-law told me that there had been a grizzly fatality in Yellowstone in July, and my in-laws were always talking about bears: bears they’d seen, what to do if you saw a bear while hiking, that kind of thing. I thought they were sort of out of their minds. What is the big deal about grizzly bears? But then when I was actually in the place, I completely understood. It’s something about how powerful they are and how humble you have to be when you’re in their territory. Also when I was at the Wyoming house, there was a book about grizzly bear attacks called Mark of the Grizzly, by a Montana-based writer named Scott McMillion. Each chapter is about a different bear attack, and they read like mini-true crime stories. I have always loved true crime and I tore through that book in an afternoon. Scott is a great journalist and he really made each story come alive. Then, a week after we got back to New York, there was the second grizzly attack, and I started really following the story very closely at that point, to see if there was a way I could sucker Slate into sending me back out West.

The real essence of the piece seems to be the conflict between bears and people: what happens when they confront each other and how, in cases when those confrontations turn deadly, we decide about bear punishment and justice. What did you come away feeling about all of it?

It’s such a complicated thing. I am incredibly sympathetic to the bear biologists whose job it is to figure out how to deal with bears that injure people. They love the bears, and it’s tragic for them to put them down. But at the same time I understand the point of view of people who think no bear should ever be euthanized. They’re grizzly bears — it’s impossible to really get inside their heads and determine their motivations with total certainty.

There’s a big question that is mentioned, but doesn’t get completely aired in the piece, which is how many bears is too many bears? The federal bear management people have been very successful in rejuvenating the grizzly population in the lower 48. But it’s not like in Alaska or parts of northern Canada: Wyoming and Montana and Idaho and Washington keep developing. So there’s more people, and there’s more bears, and grizzlies really need a lot of space. The males especially can have huge ranges. I worry that there’s going to be a point where locals aren’t so fond of bears anymore, and it’s really unclear what that will mean going forward. And if people keep getting mauled by bears, those locals will be totally justified in feeling freaked out and uncomfortable. It’s a terrible, primal thing to be attacked by a bear.

I know this is one of the first big works of longform journalism you’ve done in your career. Tell me a little bit about how that all came together.

The process started with my reading a piece in the Times about the bear involved in the first attack, and possibly involved in the second attack, getting euthanized. There was a quote in the piece from Yellowstone’s spokesman where he said, “We don’t really believe there is a way for us to definitely know which bear may have killed Mr. Wallace, or if more than one bear was involved in the fatal attack.” So to me that was a great mystery — how do they decide to euthanize a bear when they’re not sure which one was the culprit? Then Slate agreed to send me to Montana for five days back in October, so that I could at least begin to get sources and check out the parts of the Park where the fatalities had happened. The government puts out very elaborate investigation reports after fatalities, so I needed to wait on that to do a lot of reporting — a lot of the government folks wouldn’t talk to me until the Wallace investigation was officially closed, which didn’t happen until March.

One of the great things about working at Slate is that they have a thing called the Fresca Fellowship, where they allow staffers to take a month off their regular duties to work on a longform piece. As someone who has never written a nonfiction piece at this length before, my colleagues were incredibly generous and wonderful in helping me shape this, particularly my editor Dan Engber. It was like longform with training wheels, and Slate’s editor-in-chief David Plotz was so encouraging.

There’s a really gripping scene in the narrative where you and a bear expert encounter a mother and her cubs on the trail and are forced to back away slowly. [SPOILER: You are mauled to death.] Did you have any other experiences with actual bears, even if they were considerably less dramatic?

When we were at Yellowstone in August we saw a bear near the side of the road. When bears get that close to the road they always cause “bear jams,” because all the tourists stop to look at them and take pictures. This is actually a big problem for rangers in Yellowstone but that’s another story. That bear was definitely habituated to people — he was just doing some bear stuff, eating some grass, not acknowledging all the people gawking at him (or her!). When I went to do my reporting in October, I went to some small zoos in Montana where they had grizzly shows. After seeing the grizzly in the wild, seeing those bears — who by the way seemed very well fed and cared for — in captivity was depressing. I had never found zoos upsetting before but I think after reporting this story I won’t be able to enjoy them.

What did you find most surprising as you put this all together? How did it affect you during the process?

Some of the little details were really surprising and poignant. Things like, Yellowstone’s bear manager had to euthanize the grizzly on his birthday, and everything about how they tracked down the guilty grizz. Oh, also I kept having the most bananas dreams about bears while I was writing it. The best was the one where I was going to a grizzly bear-themed hotel in Paris because Harvey Weinstein (what?) had sent me and my husband there. Our hotel room had a cappuccino machine where the espresso came out of a grizzly bear’s mouth. I have no idea what that was about.

One of the biggest surprises was how many people survive bear attacks. The majority of people do. Grizzly bear attacks are incredibly rare — most grizzlies really avoid people. And most grizzlies who encounter people just want to scare them away from their cubs or their food — they don’t want to kill them.

“A Death in Yellowstone: On the trail of a killer grizzly bear” is online at Slate. Print and save for later, or read it now.

Tragedy Now Punctuated Correctly

“An article on Thursday about how Skittles, the candy Trayvon Martin was carrying when he was killed, has become a symbol of protest rendered incorrectly the name of a powdered drink that also became a symbol of protest after the cult leader Jim Jones laced it with cyanide to kill more than 900 people in Guyana in 1978. It is Flavor Aid, not Flavor-Aid.”

You Know What Was Funny on the Internet on April 1?

That’s right. Nothing.

Can we change the calendar so that April 1 always falls on a weekend? Let’s do that. Pope Gregory XIII can totally eat it.

Things Chris Jones Wished Women Treated His Semen Like

by Jeff Johnson

“Most women act as though they’re sexual Olympians, as though they’re doing the men in their lives the greatest of favors merely by presenting themselves like a downed deer strapped to the hood of a car. Some of you are deluding yourselves…. Like, maybe grab a mirror and spend some time learning how your own body works. It’s nice, too, when you don’t treat our semen like it’s battery acid.”

— Chris Jones, Esquire

.

20) Fire Jolly Ranchers

19) Arby’s Jamocha Shake

18) Soft-Boiled Egg

17) Melted Toffifay Candy

16) Steri-Fab Bed Bug Killer

15) Grape Snow Cone

14) Ed Asner’s Semen

13) George Clooney’s Semen

12) Bonnie Bell Lip Smackers Root Beer Flavored Lip Balm

11) Hawaiian Tropic Suntan Lotion

10) Wallpaper Paste

9) Green Tempera Paint

8) Banana Daiquiri

7) Miso Glaze

6) Lake Erie Water

5) Thousand Island Dressing

4) Wasabi Mayo

3) Communion Wafer Smoothie

2) Santa’s Bathwater

1) Liquid Zoloft

Jeff Johnson wants you to treat all his bodily fluids with equal kindness. Photo by Lori_NY.

How To Make Kentucky Beer Cheese For Your Final Four Party

by Brian Pritchett

Tomorrow night, when Kentucky plays Louisville in the Final Four, I’ll be sitting on my couch in Brooklyn, and filled with the anticipatory feelings of a person who, born in Lexington and brought up to listen to what his grandmother tells him to do, eschewed smart bracketology to pick the Wildcats to go all the way. And I’ll be eating beer cheese, a Kentucky specialty, with crackers and chips. It’s a simple spread, and ridiculously easy to make, and I invite you to prepare some too, because even if you aren’t rooting for the ‘Cats, or don’t care a thing about basketball, beer cheese is delicious — second only to bourbon whiskey as Kentucky’s finest contribution to global cuisine.

As with most great foods, some legend and nonsense swirls around the origins of beer cheese. But most seem to agree that it was invented in the 1940s by a Kentuckian named Joe Allman, and first served as a complimentary bar snack at his brother Johnny’s various restaurants along the Kentucky river. The Allman family still sells a packaged version, which is one of several brands available throughout central Kentucky. There’s even an annual festival dedicated to the snack.

But homemade is best, and it’s easy to do. Your main ingredients will be sharp cheddar, cheap beer and raw garlic. Start by grating a pound of sharp, room temperature cheddar. A blend of cheeses is fine, if that’s your style, but it should be a blend of various sharp cheddars. An economical strategy is to use three quarters of Boar’s Head or Cracker Barrel to one quarter of something a bit spendier. Throw the grated cheddar into a food processor.

Next, finely mince anywhere between two and four garlic cloves, according to your preference. You are going to be serving this garlic raw, so really mince it within an inch of its life, because you don’t want anyone to end up chewing on a big chunk. Also, in case this isn’t already clear, do not attempt to make out with anyone for a few hours after you have eaten beer cheese. Put the miniscule garlic pieces into the food processor.

Next up: spices. Keep in mind that this is not a mild snack, and doesn’t need a ton of help in the flavor department. So we’re going to be conservative, at first, and then mess around with the spices later to make sure we got them right. Add one teaspoon of hot sauce (I like Tabasco for this, but you can go your own way) and one teaspoon of Worcestershire. Also put in a pinch of cayenne pepper and another pinch of dry mustard powder. Turn on the food processor, and pulse everything up so that it’s all finely chopped and mixed.

Now for the star of the show: the beer. Your instinct will probably be to tart this thing up with some sort of hand-crafted Belgian masterpiece, but, like picking UNC to win the tournament, that would be an error. Beer cheese is best prepared with low-grade beer, particularly when very flat. A lot of recipes even call for the beer to be stale, which got me thinking that this whole thing was probably the creation of a barman who was trying to figure out what to do with leftover beer.

So drink the Belgian stuff, and put the old PBR that someone left at your last barbecue in the beer cheese. You need a single can or twelve-ounce bottle. If you have time, pour the beer into a bowl and let it go flat in the refrigerator overnight. If your fridge smells like the carpet from your college dorm room the next day, you nailed it. Let the beer come up to room temperature. Once you’ve pulsed the other ingredients, turn the food processor on at a low setting, and slowly add the beer via the food chute. When you’ve got about three quarters of the beer mixed into your cheese, turn off the processor and check the consistency. You’re looking for a reasonably thick spread, with a balance between beer flavor and creaminess. If you added too much beer, balance it out with a bit more cheddar. If it seems unpleasantly porridge-ish, add more beer. If the beer cheese is too watery and you simply can’t add any more products, a night chilling in the fridge will bring it in line. Keep in mind that this is not the most photogenic of foodstuffs, and a glossy photo of a batch will most likely never grace the cover of Food and Wine. This is often the case with things that are delicious.

When you’re satisfied with the consistency, check the flavor. You’ll most likely want to add some salt and pepper, but if you’re like me you’ll also add more hot sauce. There are a few other things that would make sense: a finely diced white or yellow onion, perhaps, or some horseradish or red pepper flakes. When you’re satisfied with the taste, refrigerate your beer cheese for at least an hour. It’s traditionally served with Saltines, but good with just about any cracker. Also pretzels, carrots, celery, or on toast. Or, for an Awl-inspired insane flavor bomb that is not for the timid: stuff it into some peppadews. Hope you enjoy, and let’s go ‘Cats.

Brian Pritchett is a writer and web producer in Brooklyn.

Remembering Harry Crews

by Maud Newton

In his fiction and in his life, Harry Crews empathized most with the people who needed it most: the freaks, the fuck-ups, people who’d been broken by loss of one kind or another. Crews died on Wednesday, at age 76. As his son Byron told The Daily’s Claire Howorth, “[he] put more miles on the Chevy than most of us.”

Crews lost his father, a man he didn’t remember, to a heart attack at the age of two. “It wasn’t unusual for him to fall in the field,” Crews wrote in A Childhood, to lie incapacitated on the ground for an hour or so, and then slowly pull himself up and get back to work. Soon he died in the night, as the whole family slept in the same bed. Five or six years later, Crews lost his stepfather, who happened to be his father’s brother, and it was only at their parting that Crews understood his true relationship to the man who’d raised him. “I never was your daddy, but I tried to be one to you,” the man said as he left after one final row with Crews’ mother. “I ain’t gone be by to see you no more.” He was true to his word; when Crews found him years later, they did not touch each other, “not even to shake hands.” The meeting lasted only minutes. Death and loss surrounded Crews, who also lost his oldest son to drowning.

“I’ve never enjoyed myself,” Crews told Damon Suave in 1996. “I’m incapable of enjoying myself. There’s just some people who don’t enjoy themselves very much.” “How do you like your blue-eyed boy, Mr. Death?” read the tattoo on his arm, a quote from E.E. Cummings.

Crews’ over-the-top way of existing has long overshadowed his work and affected criticism of it. He is said to have walked from Georgia to Vermont for a writers’ conference and arrived smelling like a bear. He was a Marine; he worked for a cigar factory and as a short-order cook; he once woke up after a bender with a hinge tattooed inside his elbow. He drank, and he drank, and he drank. He was known to put in a good word for Dilaudid suppositories, “Dilaudid is a sweet drug. Doesn’t last quite as long as heroin. It’s got a better rush.” He also fought, studied karate, and had some indefensible perspectives on race and homosexuality, while still brimming with the deepest compassion for humanity. He slept around and favored very young women. “[Y]ou get some gray hair on your head,” he said. “And you get some wrinkles. You got to be holding a rap — be able to talk… [I]t helps if you got some credentials…. And young girls, for some curious reason — and young girls, what I mean by that. Let’s get them old enough so we ain’t going to Raiford [a prison in North Central Florida]. I don’t know. Nineteen. Twenty. Eighteen. Nineteen. Twenty. Twenty-one. Twenty-two. Twenty-four becomes very old for what we’re talking about here… [T]hey just love old, wrinkled, ruined guys. It’s incredible.”

At the age of 73, when he spoke to Vice Magazine, Crews was waiting for a young gymnast just out of Auburn University to arrive for the weekend and cook him lobster. Not long before that, he’d spent a month in the hospital after a fight that left him with a scar starting “right in my pubes and [going] up through my navel to my sternum, where it is equidistant between my two nipples. I was gutted, man. I had my guts in my hands.”

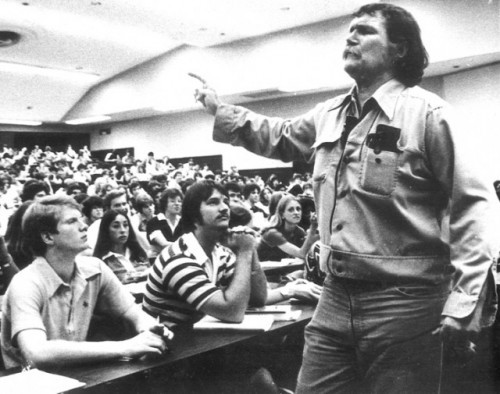

He appeared on Dennis Miller’s show and, depending on your perspective, either highlighted the host’s smarmy, smirking, shticky limitations, or revealed himself to be a total nut.

I lean toward the former interpretation. I may be in the minority, but I’m far from objective. The novelist Kevin Canty has compared studying with him to taking a class with Captain Hook. The one class I took with him in the fall of 1991 at the University of Florida was more like studying with a more dangerous, more profane, more artistic version of my grandmother, whom I revered and sometimes feared, and my grandfather, whom I’d never known but who abandoned his first child, married (something in the neighborhood of) thirteen times, was shot in the stomach by one of his wives, and was the son of a guy from Georgia who killed a man with a hay hook. You grow up hearing these kinds of stories, and someone like Crews feels more than a little like kin.

Please understand: I imply no intimacy with the man. I had none. He would not have remembered me or my writing; if he had, I would have been one of the students he denounced as a category to the New York Times, one of the “scared little people [who] come and sit in a scared little class and tremble.” I was nineteen when I signed up for the course, knowing nothing of him or his work; I could just as easily have stumbled into any other undergraduate fiction section. Sitting there in my chair on the first day, I was terrified and awed and more than slightly defiant, but I intuited as he stood at the chalkboard, drawing an incomprehensible diagram and shouting, “Fiction is an action!” that I did not have to shrink from darkness and horror in my writing, that he would welcome it.

The following summer I read everything he’d written, and then I read his heroes, Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty, and then I read it all again, and again. I did not realize then how unusual it was for a man to speak with such reverence of work written by women. Later I became obsessed with the very book he read and reread and took apart while working on his own first novel: Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, which remains to this day my favorite work of fiction. I never spoke to Crews after that class, but often think of the way he ridiculed my most worked-over sentences, the way he connected with the emotional truths, however overdramatically expressed, however unconnected to my own life, that had driven me to write the stories in the first place. He had to explain to me that an inexperienced writer really should not end a story with the protagonist shooting himself.

During an interview with him, another of his former students, Damon Suave, expressed embarrassment about his Crews worship. Crews would have none of it. Speaking of the Southern writer Andrew Lytle, he said:

“What the fuck’s wrong with that, man? I mean, what’s strange about it and what’s unique about it? Don’t you think that Lytle was god to me and that I went to see him and — in Lytle’s case, you walk in his house, and the first thing he does — a silver cup, I told you, a solid silver cup — he pours you a dollop of whiskey, and he says, anything but silver chaps our lips…

And right after the time he died in ’93, everybody else I knew that ever studied with him, called him Andrew. I didn’t call him Andrew my whole fucking life. Anymore than I would call God Jerry or something. No. He’s my man.”

John Jeremiah Sullivan, who lived with Lytle as his wood-cutter, assistant and protégée toward the end of his life, wrote a beautiful homage to his mentor. “I tried to apply his criticisms, but they were sophisticated to a degree my efforts couldn’t repay,” says Sullivan. “He was trying to show me how to solve problems I hadn’t learned existed.” Crews’ criticisms were sophisticated, too, in their remarkable simplicity, so brilliant and unreachable in their straightforwardness that I find myself repeating and puzzling over them still. Fiction is an action. Fiction is an action.

He has been called a fraud, accused of posturing, damned as a writer of caricatures. “I have found that anything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the Northern reader, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic,” said Flannery O’Connor. Some of Crews’ detractors have been Southern, but, contra David Brooks, there are many different Souths. Crews’ rings true to me (though I should add that, having grown up in Miami, despite having Southern family, I in no way qualify as Southern).

As a boy, he was a part-time hoodlum. At the age of six he stole an old woman’s hubcaps at a friend’s suggestion and, when he realized she was in a wheelchair, called back an apology as he ran down the street. He hitchhiked a lot and consequently had a lot of observations and some advice: “Go look down the barrel of a gun or feel a blade on your throat and then come back and talk to me about dying being better than getting your dick sucked.” When he joined the Marines, he did so in part “to see if I could do it,” “whether my legs were strong enough.”

“When I was a boy, stories were conversation and conversation was stories. For me it was a time of magic.” You’ll read this quote in many profiles, always taken out of context, in the way that Twain quotes are used to make him seem like some sort of kindly grandfather. Crews said this while reminiscing about his bout with polio or some other disease that left him bedridden and then unable to walk for a long time. In the beginning, his legs were so stiff he could barely move, but eventually, he wrote in A Childhood, he “could crab about over the house” with surprising speed. He liked to move just outside his mother’s sewing circle.

One of my favorite places to be was in the corner of the room where the ladies were quilting. God, I loved the click of needles on thimbles, a sound that will always make me think of stories. When I was a boy, stories were conversation and conversation was stories. For me it was a time of magic.

It was always the women who scared me. The stories that women told and that men told were full of violence, sickness, and death. But it was the women whose stories were unrelieved by humor and filled with apocalyptic vision. No matter how awful the stories were that the men told they were always funny. The men’s stories were stories of character, rather than of circumstance, and they always knew the people the stories were about. But women would repeat stories about folks they did not know and had never seen, and consequently, without character counting for anything, the stories were as stark and cold as legend or myth.

He and the other children sucked on sugar tits, which put them “into a kind of stupor of delight, just the mood to receive the horror story when it [came].” It came, usually, when the subject turned to God.

Crews wrote fifteen novels, an autobiography, and many, many essays. The University of Georgia owns his papers, among which there are myriad unfinished drafts. The strength and fury of his work surges from its — from his — bluntness. “I never wanted to be well-rounded,” he said. “I do not admire well-rounded people nor their work. So far as I can see, nothing good in the world has ever been done by well-rounded people. The good work is done by people with jagged, broken edges, because those edges cut things and leave an imprint, a design.”

His books are true, empathetic, and often cautionary, filled with freaks and losers running from their past, themselves, or the people around them. A Childhood, his autobiography, is by most critics’ reckoning, his best work. A Feast of Snakes, a novel about a rattlesnake revival, comes close, exposing the hypocrisy and strange allure of Pentecostalism with an intensity matched only by Baldwin’s Go Tell in On the Mountain. In a later book, Body, Crews suggests that you can change your name and revamp your physical self, but unless you deal with your innermost neediness, the ways life has broken you, all this transformation is counterfeit. Neither your old self nor the new one you’ve erected on top of it will be strong enough to survive the crap the world throws at you.

Amid the fistfights and the drinking and carousing, Crews was a dedicated wordsmith. “You have to go to considerable trouble to live differently from the way the world wants you to live,” he said. “That’s what I’ve discovered about writing. The world doesn’t want you to do a damn thing. If you wait till you got time to write a novel or time to write a story or time to read the hundred thousands of books you should have already read — if you wait for the time, you’ll never do it. Cause there ain’t no time; world don’t want you to do that. World wants you to go to the zoo and eat cotton candy, preferably seven days a week.”

“When I start writing, I rarely know what I’m writing about,” he once said. “Am I writing about all of those great abstract nouns that you’ve ever heard about — love, integrity, honor, compassion or whatever? The writer’s job is to take those great abstract nouns and turn them into flesh and blood and bones. Then they are real. If they aren’t flesh and blood, they’re ciphers, just names on a page. If they’re only names on a page, then you, the reader, will never make judgments about them. When I talk about judgments, I’m talking about moral judgments. Writing fiction is a moral occupation practiced by not necessarily moral men and women. I want you to make judgments. You know, your sympathies and your heart and even your hope will go out to this guy, who ain’t a guy at all, he’s scribbles on a piece of paper; but he is, you know him, you know what he wants and what he’s willing to give up to get it. And then he starts to do something and you say, ‘Oh, man, c’mon, don’t do that,’ and he does it anyway.”

His biographer, Ted Geltner of Valdosta State University, last saw him in November. “His health was terrible,” he told me yesterday. “He could barely get from the bed to the wheelchair, but somehow he was still managing to work on a novel. He was in constant pain, but he still was willing to sit with me and relive old memories, seemed to enjoy telling stories when the pain subsided, cracking jokes throughout.”

A world without Harry Crews is hard to reckon with. But then, in life as in fiction, “Everybody comes to grief over endings. Closures as they like to say.”

Maud Newton is a writer and critic best known for her blog, where she has written about books since 2002. Bottom photo courtesy of the University of Georgia’s Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, which houses Crews’ collection of manuscripts and personal correspondence; via.