A Brief History Of Pop Stars Dressed Like Bees

David Letterman REALLY liked the dress that Alicia Keys wore on his show last night. I think she looked liked a bee. She would not be the first pop star to look like one!

The last time I saw someone in an outfit that looked so much like a bee was in 2002, when Nas posed in this crazy fur coat for the cover of XXL magazine. He looked a lot like how I imagine Sting looked the night that he got his nickname in the mid-’70s. Performing at a jazz club in London (as, of course, was his wont) he wore a yellow-and-black striped sweater that reminded bandleader Gordon Solomon of a yellow jacket’s jacket. The name stuck. It is surely a sign of his monstrous vanity that there are no photos available of Sting dressed up like a bee since. (Come on Sting, lighten up, huh? Imagine what a kick Letterman would get out of you showing up on his show in Alicia Keys’ dress.)

Around that same time, John Belushi starred as a “killer bee” in a recurring skit on “Saturday Night Live.” When he and Dan Aykroyd began performing musically as the Blues Brothers, Belushi sang a version of the Slim Harpo classic “I’m a King Bee” in costume.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YE-WTzYD0Us

In 1993, the Los Angeles rock band Blind Melon joined the young actress Heather DeLoach in dressing up like bees in the video for their hit song, “No Rain.”

In 1997, The Wu-Tang Clan took the form of a swarm of “killa bees” in the video for “Triumph.”

That same year, in the video for Puffy’s “All About the Benjamins,” Lil Kim wore black-and-yellow stripes to deliver her famous rhyme “Wanna bumble with the bee, huh?/Bzzz/I’ll throw a hex on your family…”

I wish Frank Black had made a video for the title track of his great 2005 album, Honeycomb that featured him dressed up like a bee. But he didn’t. It’s still a great song, though.

And then of course, the ever charming Blackie Lawless of W.A.S.P. often dresses up like some sort of chimerical wasp-tiger-chainsaw monster unleashed to terrorize the world. That’s kind of like a bee.

The Internet's Vigilante Shame Army

by Whitney Phillips and Kate Miltner

In 2012, more than ever, the internet became the way we shame people now. Here to talk about online justice and public shaming are academic internet experts Whitney Phillips and Kate Miltner. (Whitney recently completed her PhD dissertation on trolls; Kate wrote her Masters thesis on LOLCats — yep!) Up for discussion today: Violentacrez, hate blogs, racist teens on Twitter, poor Lindsey Stone, Hunter Moore, and last Friday’s misidentification of the Sandy Hook shooter.

Whitney: Contrary to Nathan Heller’s Onion-worthy New York Magazine article lamenting the loss of the “hostile, predatory, somewhat haunted” feel of early web, the internet of 2012 is not always a warm and fuzzy place. In fact it can be pretty terrible, particularly for women, a point Katie J.M. Baker raises in her pointed response to Heller’s article. The internet is so far from a utopian paradise, in fact, that lawmakers in the US, UK, and Australia are scrambling to do something, anything, to combat online aggression and abuse.

Not everyone supports legal intervention, of course. Academics like Jonathan Zittrain readily concede that online harassment is a major concern, but they argue that the laws designed to counter these behaviors risk gutting the First Amendment. A better solution, Zittrain maintains, would be to innovate and implement on-site features that allow people to undo damage to someone’s reputation, livelihood, and/or peace of mind. As an example, during an interview with NPR, Zittrain suggested that Twitter users could be given the option to update or retract “bad” information, which would then ping everyone who interacted with the original tweet. Existing damage would thus be mitigated, and draconian censorship measures rendered unnecessary.

Regardless of the impact that either type of intervention might have, the fact is that today, this very second, there is often little recourse against behaviors that might be deeply upsetting, but aren’t quite illegal either. In those cases, what should be done? What can be done?

If recent high-profile controversies surrounding Violentacrez, Comfortably Smug, racist teens on Twitter, Lindsey Stone and Hunter Moore are any indication, it would seem that many people, members of the media very much included, are increasingly willing to take online justice into their own hands. Because these behaviors attempt to route around the existing chain of command (within mainstream media circles, the legal system, even on-site moderation policies), I’ve taken to describing them as a broad kind of online vigilantism. It might not be vigilantism in the Dog the Bounty Hunter sense, but it does — at least, it is meant to — call attention to and push back against some real or perceived offense.

Kate: The first thing to point out is that a lot of this online vigilantism takes the form of shaming — and surprise, surprise, this sort of behavior is not unique to the internet (Channel 2’s Shame On You, anyone?) . As a cultural practice, shaming goes back centuries, probably millennia. It’s one method of enforcing norms — those unwritten, extra-legal, societal rules that dictate (or at least influence) how we behave. Only now, instead of making norm violators run around wearing big red As on their chests, we make Facebook pages that exhort people to “LIKE THIS IF YOU THINK HESTER PRYNNE IS A DIRTY SKANK! >:-O”

Shaming is a tool that people use for all sorts of reasons — not only to enforce norms, but to feel superior, exact revenge, make a joke, etc. Public humiliation and shaming were used for centuries as judicial punishments — there’s a reason we use the word “pilloried” in shaming contexts. According to law professor Daniel Solove, humiliation-based punishments subsided as the prison system developed; they were eventually outlawed on the grounds that they were cruel and unusual forms of punishment. Despite this categorization, Solove contends that certain types of shaming can be useful in that they give people a chance to fight back and can deter potential offenders from engaging in unacceptable behavior. (He offers up customer service forums and sites that combat street harassment, such as Hollaback, as examples of that sort of ‘beneficial’ shaming).

In the case of Violentacrez and Hunter Moore, shaming was used to fill a legislative void and provide recourse in the absence of a meaningful legal solution; one of the reasons people engage in this type of behavior is because they feel it is their only option for achieving justice. Moore, “The Man Who Makes Money Publishing Your Nude Pics” and proprietor of now-defunct “revenge porn” site Is Anyone Up?, was doxxed by Anonymous for his remorseless victimization of women. Violentacrez, “the creepy uncle of Reddit” and creator/moderator of several exploitative subreddits (including /r/jailbait and /r/creepshots) lost his job and became known as “The Biggest Troll On The Web” after his identity was revealed by Gawker’s Adrian Chen, and everyone then knew that Violentacrez was a 49-year-old guy from Texas named Michael Brutsch.

The things that Brutsch and Moore did aren’t technically illegal, but clearly cross many moral boundaries. So, because there wasn’t much that could be done from a legal perspective, people took matters into their own hands and meted out their own form of punishment.

Another notable example of this is the Megan Meier case, the teen girl who committed suicide in 2006 after being cyber-bullied on MySpace by the mother of a friend. As a result of the outcry that followed Meier’s death, legislation ended up being passed that expanded existing harassment laws. So, yes, I suppose Solove has a point when he points out that shaming isn’t necessarily all bad, but also, eesh — what an incredibly slippery slope.

Whitney: Yes, just because it’s an option, doesn’t mean it’s a good option. In the end, online public shaming may create its own problems. So before anybody throws themselves a vigilante-themed cosplay party, it makes sense to slow down and consider how public shaming works (or doesn’t work) online.

First, and this is a critical point, shaming often involves crowds. “The hivemind,” in internet parlance. Sometimes the hivemind acquires its target in grassroots fashion, for example in the Lindsey Stone case. The outrage many people experienced upon seeing/hearing about one of Stone’s Facebook photos — which showed Stone mugging disrespectfully in front of a “silence and respect” sign at Arlington National Cemetery — prompted someone to create a “Fire Lindsey Stone” Facebook page, which quickly amassed several thousand followers and ultimately resulted in Stone being fired from her job.

Yes, but branding people with their worst decisions and keeping them excluded from mainstream society isn’t just about deterring the guilty party. These kinds of deterrents — capital punishment being the most obvious example — are as much about scaring everyone else straight.

In other cases, the hivemind is spurred to action by external amplifiers, which is where questions of accuracy become particularly important. We saw this last Friday with the tragic shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary. In this case, a number of media outlets — all of whom were scrambling to piece together as much information as quickly as law enforcement was providing it — identified the shooter as one Ryan Lanza of New Jersey, a report that came from police that proved false. Adam Lanza was the actual shooter; Ryan Lanza was his brother. Adam had been carrying Ryan’s ID, hence the misidentification. Not only were these initial reports confusing, they triggered a whole slew of nasty mob behaviors, including speculative laundry– (and even home address)-airing as well as outright harassment of the Ryan Lanza who turned out to be the shooter’s brother and all the other “Ryan Lanzas” who had the misfortune of having searchable social media profiles. Even the friends and followers of the Ryans/Adams in question were subject to abuse (see this article by Matt Bors, who was inundated by hateful messages simply by being Facebook friends with the “real” Ryan Lanza).

Kate: I think that CUNY professor Angus Johnston put it quite well:

News just showed video of Ryan Lanza. FB, Twitter, and the national media sent a mob after a guy whose whole family just died. Nice work.

— Angus Johnston (@studentactivism) December 14, 2012

The other issue that Johnston’s tweet highlights is that, in our era of “citizen journalism,” it’s not just media outlets who are involved in this process, but any person with a social media account, all of whom seem to get caught up in an unfortunate game of FIRST!!11!

The super-reactive and impatient nature of crowds, particularly when it comes to very emotional events like Sandy Hook, means that people will circulate (and in Ryan Lanza’s case, act upon) anything that looks like news, even if it hasn’t been verified. This is why people were so angry when they found out that Comfortably Smug was intentionally posting misinformation on Twitter during Hurricane Sandy. He manipulated an urgent need for news during an emergency to basically mess with people. He knew very well that what he was putting out there would spread fast and far, because that’s what happens in these sorts of situations.

People seem to be getting more sensitive to the accuracy of information that is spread around social networks (particularly Twitter) during crisis events. Xeni Jardin — along with dozens of others — took some heat for circulating incorrect details about the identity of the Sandy Hook gunman and defended herself by arguing that this sort of rapid information-sharing is how we collaboratively process these sorts of things.

Shooter confirmed as “Ryan Lanza.” A FB link is circulating. Ryan John Lanza, 4/10/1988, from Newtown. On voter records as Republican, FWIW.

— Xeni Jardin (@xeni) December 14, 2012

Oh fuck off, people. The link was circulating, this is how we process things collaboratively. I did not say he was confirmed as shooter.

— Xeni Jardin (@xeni) December 14, 2012

Now, to be fair to Jardin, she was only reporting what the police had confirmed — that was their mistake, not hers. And yes, Twitter does allow us to collectively report and process information. However, the problem with the “Internet Truth Machine” is that, while eventually we get the story straight, the messy process of confirming actual, verified facts no longer takes place behind the doors of a newsroom, but publicly and in real time. This means more transparency, but it also means that any person can pounce on a potentially incorrect piece of information and run with it, whether that means a retweet or something less innocuous. This is why journalists and other amplifiers/influencers have a particular responsibility to ensure that the information they’re putting out there is correct. Which, in practical terms, means waiting before they tweet — even at the risk of being late with the news.

Whitney: Of course, the idea that journalists should wait any amount of time runs up against their job descriptions, which is to report what happens when it happens. Problems arise when the “facts” they do report are, in fact, not factual, or when they don’t bother to strongly qualify “not sure if legit” retweets (an admittedly difficult task in 140 characters), or when what they’re passing along is no more than sensationalist hearsay — all of which risks inciting the angry online mob before the full details of the story have a chance to shake out. Mashable’s Lance Ulanoff has a few harsh words for precisely this impulse:

No one waits for the facts anymore, least of all online media. It is “find and run with it.” All apologies can come later. It’s just media, after all. Just digital words and images, easily changed with the stroke of a key. People will read the update or the updated post. So it’s all good, right?

Except it’s not.

It matters because journalistic carelessness is damaging. It represents a basic disregard for what is true in favor of what is first, fast, and clickable, an attitude that, as mentioned earlier, risks encouraging knee-jerk and often irresponsible vigilante behavior — or as this Telegraph article describes, crazed amateur detective work.

But stirring the hivemind isn’t the only problem with the “report now, ask questions later” attitude. This frenzied clamor for information, even for false or partial information (both on the part of journalists and the public), only amplifies the powder-keg relationship between breathless media coverage of mass shootings/suicides and future mass shootings, a point Charlie Brooker discusses in this must-watch clip, and which feminist media scholar Carol Stabile addresses in a recent blog post. Given this relationship, I would argue that the incomplete, speculative or otherwise sensationalist reports to emerge in the wake of Sandy Hook are every bit as problematic, if not more so, than the handful of trolls who have created offensive parody accounts, and whom law enforcement in Newtown are now threatening to file charges against.

Kate: Agreed, and ugh. Of course, the Sandy Hook case is an extreme (and extremely upsetting) example. It’s important to point out that not all cases of shaming/online vigilantism are equal, or provoke the same level of outrage.

In the case of Lindsey Stone, it seemed that things started off with finger-wagging and then ended up escalating to a call for her head/job — a reaction that some felt to be incredibly unfair and disproportionate. This illustrates one of the major problems with online shaming, which is that the outcome often ends up being different from the original intent: what starts off as a “tsk-tsk-tsk” ends up being a permanent, often life-damaging record of the shaming targets’ mistakes and/or transgressions. The internet never forgets, which is why some people, including philosopher/law professor Martha Nussbaum and researcher Brene Brown, think that shaming is inappropriate no matter what the situation, because the punishment ends up not fitting the crime (i.e., being fired over a silly picture).

Nussbaum and Brown both argue that shaming is too damaging to be used in a civilized society, because they target the person (“you are innately bad”) vs. the person’s acts (“you did a bad thing”). Nussbaum points out that the point of shaming is to alienate the “defective” person from society by marking them with a degraded identity (in this case, a nasty Google history). Short of a name change, these people are saddled with this stuff for life. Which, I suppose, can be a good or a bad thing depending on your views on rehabilitation and the ability of human beings to change. Personally, I don’t think that branding people with their worst decisions and keeping them excluded from mainstream society is the best way to deter them from behaving badly — there are lots of maxims about people with nothing to lose, and they exist for a reason.

Whitney: Yes, but branding people with their worst decisions and keeping them excluded from mainstream society isn’t just about deterring the guilty party. These kinds of deterrents — capital punishment being the most obvious example — are as much about scaring everyone else straight as they are about discouraging recidivism. So it’s not just “I don’t want to be executed so I shouldn’t commit any more crime,” but also, and perhaps more importantly, “I better not start committing crime because I don’t want to end up like that guy they just executed.” These types of deterrents are, in other words, fundamentally pedagogical. They teach us what we can and cannot get away with. The same goes for acts of online vigilantism. Like more traditional offline deterrents (if you kill people, we will kill you, so don’t kill people), online shaming allows certain individuals or groups to model what is and what is not acceptable within a specific (sub)cultural context. But not just model — the second (and simultaneous) half of that equation is punishing, or threatening to punish, anyone who deviates from whatever established norm.

Take the Jezebel racist teens piece, which publicized the names, social media profiles and schools of the accused teenagers. One can criticize (and I have criticized) Tracie Egan Morrissey for this approach, particularly the fact that she unfairly implicated an innocent 15 year old in her anti-racist dragnet (not to mention the fact that she inadvertently incentivized anonymous racist expression). But in order to fully engage with the story, it’s critical to remember that she wasn’t just focused on these specific teenagers. She had much bigger fish to fry, namely all those people who haven’t been called out for their racism. Morrissey was sending them the unequivocal message that YOU SIMPLY CANNOT SAY THIS SORT OF SHIT IN PUBLIC, AND IF YOU DO, YOU’LL BE SORRY, a point echoed by many of the article’s commenters. In other words, if you step out of line, you will be punished — because you deserve to be punished.

Kate: Right, but the problem is that I don’t think that “THIS COULD HAPPEN TO YOU” is particularly effective. (If this Deadspin piece on racist reactions to Obama’s Newtown address is any indication, Egan Morrissey might as well have been shouting at a brick wall.)

History is filled with cases of people being turned into examples of where the targeting didn’t have the intended effect, and even crossed over into backfire territory. This is particularly true when the targets are poorly chosen. In the realm of recent history, the RIAA tried using the “selectively sue” tactic with illegal downloaders (Napster! KaZaA!) in an attempt to scare all of those durn teenagers who were robbing multinational conglomerates of their chimney-sweeping wages (I don’t mean to make light of piracy because of artists rights and compensation, but I don’t think that these suits were really about artists losing money). What ended up happening is that a few of the “worst” offenders went to court, the RIAA looked pretty stupid, and everybody else kept downloading whatever the hell they wanted.

You brought up a key point about shaming targets “deserving” to be punished. One thing that I’ve noticed in quite a few of these cases is that a rhetoric of blame comes into play. And the blame often centers around the public nature of the activity as well as expectations of digital literacy — i.e., the shaming behavior is not only justified because the target did something “wrong,” but also because they were stupid enough to do it on the internet. I mean, the internet has been around long enough at this point, MORONS — what else can they expect when they post (X Y Z type of content) online? It’s their own fault, they totally should have known better. But that rhetoric comes scarily close to other types of victim blaming that most people no longer consider acceptable. For example, “What else can you expect when you go out in public after midnight wearing a short skirt? It’s her own fault, she should have known better.”

And in many instances, that border verges on non-existent. Misogyny is a major theme when it comes to online shaming — to quote Adrian Chen ,”nothing gets the online hive mind’s psychotic rage juices flowing better than a young woman who it feels is out of line.” Both Kiki Kannibal and Amanda Todd were excoriated for being “sluts” online. Todd was pressured (and then blackmailed) into baring her breasts to a man she met in an internet chat room. After a topless photo of her was released online, Todd experienced harassment so severe that she committed suicide. Kannibal was unfairly blamed for the death of her ex-boyfriend (who also raped her); after she received death threats, her family had to relocate. But hey, they totally asked for it, right? Disgusting.

Where once you (mostly) had distinct, separate communities with norms that were policed within those communities, we now have more of a mish-mosh where people with conflicting values end up policing each other, which makes things very messy.

Whitney: That’s not the only problem with “asking for it” rhetoric. This same sort of victim blaming is pervasive within trolling circles, and provides an interesting analogue to social justice vigilantism. (Is that a phrase? It is now) To trolls, the fact that someone has been trolled is proof that they should have been trolled. The target’s anger or frustration or distress thus functions as simultaneous goal of and justification for the trolls’ actions. And with good (well, maybe not good, but “valid,” i.e. the conclusions follow logically from the premises) reason, since according to trolls, nothing on the internet should be taken seriously — an imperative that doesn’t just allow for but in fact encourages pushback against sentimentality and emotional attachment. Of course, “nothing on the internet should be taken seriously” is a universalizing, (not to mention self-contradictory) assumption, one that is very easy to make when you have the option — which is to say, the privilege — of remaining anonymous. But for those who accept this premise, it is extremely easy to justify punishing those who fail to adhere to how people on the internet “should” behave.

Significantly, the same vigilante rhetoric used by trolls is almost interchangeable with the rhetoric used by those engaged in other forms of online shaming (danah boyd discusses the behavioral mirroring between trolls and those who would unmask them here). Some universalizing assumption — nothing on the internet should be taken seriously, everything you have ever said on the internet can and should be held against you forever, people have the right to say and do anything on the internet with absolute impunity because free speech — is forwarded, simultaneously establishing the boundary of what is and what is not acceptable, and reifying (what is presumed to be) a clear-cut distinction between the “us” who punishes and the “them” who (ostensibly) deserves punishment. And this is where the specific details of a given case — specifically, what borders are being policed by whom — become critical to assessing the ethics, or lack thereof, of vigilante interventions.

Kate: Right, and this is complicated by the fact that the boundaries between specific pockets of internet are collapsing and blurring. So where once you (mostly) had distinct, separate communities with norms that were policed within those communities, we now have more of a mish-mosh where people with conflicting values end up policing each other, which makes things very messy. For example, what is considered to be acceptable (or at least, not particularly problematic) on certain parts of Reddit can be very different from what is considered to be acceptable in “mainstream” internet circles. That wasn’t an issue in the early days of the site when it was mostly self-contained, but now that Reddit provides endless fodder for mainstream news outlets, the libertarian ethos that errs on the side of “freedom to” vs. “freedom from”* (i.e., “freedom to post upskirt shots of teenagers” vs. “freedom from exposure to content that most people would find disturbing”) is more problematic. For non-redditors, it may be totes cool that Obama did an AMA and Advice Memes are being used to sell Kia Sorentos, but not as cool that /r/deadjailbait exists.

This clash is not exclusive to Reddit, either — you can also see it with certain hate-blogs. The hate-bloggers (which is a problematic term for me, but that’s another post) will stumble upon a blog/blogger whose modes and ways of being are completely nauseating/repulsive to them, and react by posting snarky takedowns (“they put this drivel in the public arena, I am within my right to publicly point out that they are a-holes”). And to be honest, sometimes I’m totally reading along in smug mode, particularly when the targets of their ire are misogynist/classist/otherwise offensively ignorant. The targeted bloggers see it as harassment, the hate-bloggers and their audiences see it as justified criticism, and we’re back to square one.

Whitney: But maybe that’s not a terrible place to end up, because it means we can’t easily rely on any facile, forgone conclusions. My personal take (and in the spirit of back-to-square-one-ing) is that the question of whether or not public shaming is GOOD (effective, humane, passes utilitarian muster, etc) is contingent on a number of factors. First, which nouns and verbs are scribbled into the Mad Libs template ([PERSON] violated the maxim that [UNIVERSALIZING ASSUMPTION] and therefore deserves to be taught a lesson by [GROUP])?

Furthermore, what assumption is being universalized? In the case of Hunter Moore, for example, I accept the basic assumption that one should not be a woman-hating dickbag, and so have no problem when the internet decides to give him a healthy dose of his own medicine. I do not, however, accept the premise that posting a stupid, ultimately juvenile photograph (of which I have been the subject of many, as has everyone) to Facebook justifies being fired, so think that what happened to Lindsey Stone sucks.

Finally, the efficacy/ethics of vigilante tactics depends on the accuracy of the information provided. Any vigilante intervention based on false or misleading information is something from which we should back away slowly. The problem is that it’s often difficult to know what information is true and what information is false, particularly if we’re watching the story unfold on Twitter. One possible solution is to stop blindly accepting and amplifying information we see on Twitter — after all, and to echo the Lance Ulanoff piece mentioned earlier, it is better to be right than to be first, particularly when you consider the potentially devastating consequences of getting things wrong.

In the end, then, how I feel about public online shaming has less to do with how I feel about the method itself, and more about the details that animate each particular case.

Because the truth is, there’s an awful lot of unconscionable shit on the internet. Merely shrugging our shoulders because “that’s just how people are online” is akin to apologizing for incidents of sexual assault on the grounds that “boys will be boys.” That position isn’t just defeatist, it reifies existing systems of power, and almost guarantees that the behaviors in question will continue. And waiting for the proper authorities to intervene, and not just intervene but intervene reasonably and effectively — I wouldn’t hold my breath. Given all that, yes, sometimes people do and will continue to need to take matters into their own hands. Which isn’t a ringing endorsement for anything, but rather functions a neon CAUTION sign, flashing in all directions.

Kate: This reminds me quite a bit of the whole free speech conundrum. Free speech is really great when it is being used the “right” way, and terrible when it is being used the “wrong” way. For me, it is great when free speech is used to defend against abuses of power and other such things; it is terrible when, for example, white supremacist groups get to spew their vile vitrol with impunity. If you are the Westboro Baptist Church, it is great that you get to picket military funerals, and terrible that you can’t stop Those Awful Liberal Freedom-Killers from telling people that yes, it is perfectly acceptable to be gay, and that gay people deserve equal rights. Conflicting value systems! They make everything so complicated.

Whitney: It’s interesting you mention the WBC, particularly their mind-bogglingly inhumane decision to picket Sandy Hook Elementary. This is one of those cases where vigilantism strikes me as the best, and perhaps the only, means of pushback. For some reason, this hate group (which isn’t even legally recognized as such; rather it is classified as a legitimate religious organization and currently enjoys tax exempt status) is free to pollute the airwaves and street corners with a seemingly endless supply of insane, toxic, incendiary bigotry, a fact I have never fully understood, particularly in this case (if ever there were a time to play the incitement to violence/fighting words card, picketing the funerals of twenty murdered 6 year-olds on the grounds that gay people exist would be it — though I suppose that’s a tall order for a government that doesn’t recognize these same gay people as equal under the law). No one should have to see or hear that sort of thing, least of all those personally affected by the tragedy. So when I heard that Anonymous had declared war on the WBC and that the Jester, a well-known activist hacker, had taken down an obnoxious troll account mocking the Sandy Hook victims, I tipped my hat to them. Because good.

Kate: I agree that we shouldn’t just stand idly by while people are victimized, but the problem with the nature of online shaming as it currently stands is that once the hounds are unleashed, they go for broke, no matter what the original crime was. For that reason, along with the other tricky points we’ve discussed, online vigilantism just makes me uncomfortable — even though I may cheer at some of the outcomes (WBC, etc).

In the end, I think that a lot of this comes down to a certain sense of moderation and reason. I don’t think this behavior is going away anytime soon, so ideally, we’ll develop some sort of normative standard around proportionality — i.e., don’t ruin someone’s life for doing something that any person could have done in a moment when his or her judgment was lacking. Compassion and reason are (kind of) built into the legal system, it should apply to the internet as well. We no longer throw people into jail for life for stealing a loaf of bread; people’s lives shouldn’t be ruined because they posted something stupid on Facebook. We should be able to say “this is not okay” without resorting to catastrophic punishments.

However, until schadenfreude and moral panics stop being good for ratings/pageviews/upvotes/likes/retweet counts, I worry that won’t be the case. Using other people’s humiliation and/or “just desserts” as entertainment (dramatic or humorous) is as timeless as shaming itself — moderation and reason aren’t fun to watch. We are not dealing just with individual instances of specific behavior, we are dealing with a system in which we are all complicit, and that is a much, much harder thing to change.

* Thanks to Mary L. Gray for this framing.

Previously: The Meme Election: Clicktivism, The Buzzfeed Effect And Corporate Meme-Jacking

In the Summer of 2012, Whitney Phillips received her PhD in English (Folklore/Digital Culture emphasis) from the University of Oregon. Her dissertation, titled “This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: The Origins, Evolution and Cultural Embededness of OnlineTrolling,” pulls from cultural, media and internet studies, and approaches the subject of trolling ethnographically. She writes about internet/culture here and here and is currently a lecturer at NYU.

Kate Miltner is the Research Assistant for the Social Media Collective at Microsoft Research New England. She received her MSc from the London School of Economics after writing her dissertation on LOLCats, something for which she has been mocked mercilessly in the comments sections of Gawker, The Huffington Post, Mashable, Time Magazine, and the Independent. She has also written about internet culture for The Guardian and The Atlantic. You can find out more about her at katemiltner.com.

The authors would like to thank Chris Menning at ModPrimate and the Social Media Collective at Microsoft Research for their input and support.

What Is Causing Your Headache?

“The National Headache Foundation suggests patients might want to limit their intake of tyramine, a chemical that occurs naturally in certain foods, to help control headaches. Here are some foods containing tyramine or other substances believed to be headache triggers:” [SPOILER: anything GOOD.]

The Future Of Lethal Automotive Accidents

Here’s the way we’ll crash then: Dutch aeronautics company Pal-V’s prototype car/helicopter the Pal-V One. Scheduled to go on sale in 2014, the Pal-V One conforms to international laws of both flying and driving. It needs just 200 meters to take off, and costs $300,000, which is not so much money to spend to maim or kill yourself by crashing into a building.

Wurtzel, Crichton & Yoo: Inside The Delightful 'Harvard Crimson' Archives

Wurtzel, Crichton & Yoo: Inside The Delightful ‘Harvard Crimson’ Archives

A series on the stuff that delighted us on the Internet this year.

In my case, this year’s Internet experience didn’t suck, exactly, but it was — at least in the precincts I frequent — drearily focused on the predictive. Ninety percent of what I read, excluding pornography, maybe, was either authored by, a celebration of, or a brief against Nate Silver. And that’s nice! On balance, that a smart, gay adopted son of Brooklyn is a big deal is a good thing. But oh, how I wish we purveyors and consumers of the written word would spend a bit less time quantifying the probability of future events and a bit more time salvaging our culture’s diminishing paper trail. We will assuredly regret neglecting our back pages.

I sound like white-haired Henry Larson of Home for the Holidays, who, amid a Thanksgiving dinner grace, shakes a fist at the inevitable as he observes that “thousand-year-old trees are falling over dead — and they shouldn’t.” But they will, as surely as our tree-pulped books, newspapers and magazines will, in turn, vanish along with the ozone layer. This breaks my heart. My son is nearly three months old. When he’s my age, what are the odds he will be able to get his hands on obscure, brilliant works such as John Howland Spyker’s Little Lives or an issue of The Noble Savage?

Of course, he may not want to. Not everyone mourns the absence of newspapers and books you can hold in your hands, or believes we ought to digitize these crumbling pages. But I am increasingly obsessed, increasingly complete-ist. At risk of self-aggrandizement, it does matter that young Maureen Dowd was a peerless metro reporter and that Tobias Wolff buried a great first novel. Shouldn’t a future assessment of these writers take this into account?

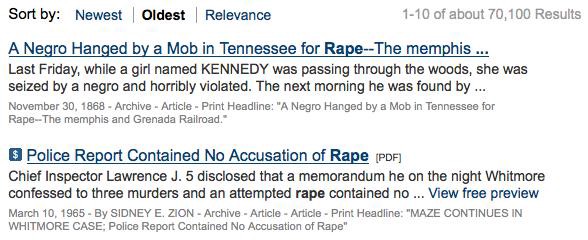

Efforts to solve this archival problem are underwhelming. It seems our best hope is a Google Roomba. So I’m not optimistic, particularly with the long-term digitization prospects of newspapers. Even The New York Times archive, which professes to be “complete,” has gaps the size of the South Pole–Aitken basin. If one believes the Times search engine, the word ‘rape’ did not appear in print for nearly a century.

So: The bar for online archivization, set at dirt-level, is easily cleared by the Harvard Crimson, the university’s daily paper. I discovered it this year, and have now spent hours trawling through its archives. While there’s very little from the early years — only one clip from Franklin D. Roosevelt (‘04), for example — but the post-World War II era is quite thorough; Crimson president E. Benjamin Samuels says that “above 90 percent” of that period’s clips have been put online. There is no subscription required, so for the price of a smile one gets a delicious peek at generations of whiz kids, mastering the upside down pyramid on the way to success in journalism and elsewhere. Aside from singing Yoda, it’s my favorite thing on the Internet (which, ugh, we are still capitalizing?).

Herewith is some Crimsonalia I treasure.

DAVID L. HALBERSTAM ‘55

The multi-decade atrocity that would make Halberstam’s name, the Vietnam War, would begin the year he graduated, so there’s more Summer of ’49 than The Best and the Brightest in his Crimson clip file. Via Jack Bohrer, a perfect lede from November 18, 1954:

When Army visited New Haven some ten days ago, it broke several things: 1, the Elis’ six game winning streak; 2, fullback Steve Ackerman’s collarbone, and 3, it would seem, much of Yale’s October bred confidence.

Halberstam occasionally detoured: he rounded up the campus reaction to Earl Warren’s imminent appointment to the Supreme Court and wrote about Cambridge’s lean police force. At least once, he tried his hand at theater criticism. He hated Janet Green’s Gently Does It, but praised Mabel Taylor, who played the family servant; “she is provincial, she is hunched over, she is always properly subservient and sufficiently stupid.”

Nearly a half-century later, Halberstam told a Crimson reporter he was a “terrible student,” but “I was good at The Crimson, and it was the one thing I was good at.”

MICHAEL CRICHTON ‘64

Or J. Michael Crichton — as his byline appears in the Crimson (he shared the given name with his father, who he described as a ‘first-rate son of a bitch’). What’s striking about his contributions is his knack, already well developed in his late teens, for dramatic pronouncements about the Earth and its inhabitants. Nearly twenty years before he decried the notion that humans could destroy the planet as “intoxicating vanity” — mighty convenient, you might say, for a skeptic of global warming — he suggested in a review of Robert Ardrey’s African Genesis that man “may indeed destroy himself. But we need not feel that it is a foregone conclusion, or that it is our particular destiny.”

To be sure, there was a lighter side to J. Michael. His profile of Smith College students contains a quote so good it’s a shame he didn’t stick with journalism:

One small, defensive-looking girl, when asked what she did when a big Dartmouth animal got out of hand, smiled and said, “It’s really quite simple. If he is being very obnoxious, you just pull back, look him straight in the eye, and say coldly, ‘Frankly, you don’t appeal to me at all.’ It never fails.”

The next year, he reviewed Tom Jones (“a wild, ridiculous, engaging film and seems sure to become a minor classic”) and covered a student lunch with Dr. Benjamin Spock, during which the Crimson correspondent was careful to note the doctor’s remarks on the drawbacks of a fame particular to an author whose Baby and Child Care had sold fifteen million copies: “It can be quite disturbing sometimes. There’s always the woman with the most illbred brat on the block, who boasts she raised the child exactly according to my instructions,” Spock told the undergraduates of Lowell House. “I really tremble to think what I’m apparently responsible for.” Crichton, a Crimson colleague recalled upon his death, “was a master of all the disciplines.”

PETER W. KAPLAN ‘76

The New Republic put it well recently: Peter Kaplan, they said, is seen as “a spokesman for the hoary charms of screwball comedy and ink-stained fingers.” The Crimson archives reveal that the one-time New York Observer editor has always been that guy, even when he was barely old enough to drink. [Here’s where I disclose, needlessly, that a decade ago I was Kaplan’s editorial assistant. Mostly this meant answering his phone and telling Nikki Finke “he isn’t unavailable.”] This review of The Day of the Locust is the work of an undergrad with the soul of Harold Ross:

I wish that when John Schlesinger had made Day of the Locust he had paid a little attention to S.J. Perelman … so that he could understand at least a little bit about satire. Satire is not soap opera, which this new movie is. I wish he had taken West’s images and terseness somewhere, anywhere. I wish he had a sense of the crazy and of the really grotesque, not just the horrible. None of this says very much about the film I’m afraid, because there will be a good evaluation of it in this paper by someone else on Monday. But if you were thinking of seeing it over the weekend, my advice is: don’t, I say it’s spinach and I say the hell with it.

The “advice” dispensed by 21-year-old Kaplan is cadged from a 1928 New Yorker cartoon captioned, but not drawn, by E.B. White. It would go on to be well-quoted in the Observer, three times by Michael Thomas alone.

GROVER G. NORQUIST ‘78

Norquist’s Crimson tenure is marked by a willingness to cover just about anything, be it a proposed addition of a neon news marquee to the beloved Out of Town News (which is still in business, somehow!), a Harvard-Radcliffe track meet or the news that Harvard’s business school enjoyed a bump in applications.

It’s hard to recognize the now-ubiquitous anti-taxer in the young reporter, but there’s a hint of his politics in, of all places, an ode to cross-country skiing. It was a diversion about which he was passionate:

The hard waxes generally come in small foil cans while the soft waxes, or “klister” in Swedish, come in tubes, like toothpaste. (The hardness of a wax is determined by the proportion of wax to resin, and the klister is almost entirely resin.)

The waxing chart above is a demonstration of how snow conditions and temperature combine to determine the optimum wax.

While you may be anxious to begin skiing and want to rush out and outfit yourself with Norway’s finest, the temptation to buy immediately should be fought.

Norquist, who would famously yearn to shrink the government to a drownable size, concludes that one of the joys of cross-country skiing, as opposed to downhill, is it “doesn’t require ten-dollar lift tickets, two hour rides in search of ‘skiable snow,’ or equipment that would bankrupt the U.S. Treasury.”

When I contacted him recently, Norquist said he considered joining the Lampoon, but chose the Crimson because it was the summer and “there was nothing else to do.” Nicholas Lemann, now the dean of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, was the top editor, and there was a fight between Eric Breindel and Jim Cramer to succeed him. Lemann chose Cramer, says Norquist, because “even though Breindel was a good socialist, he was a Zionist, which put him beyond the pale.” (Lemann disputes this.1) Politics, says Norquist, were also an obstacle to his ascension at the paper. “I could never have moved up too much. Everybody knew I was conservative-libertarian.”

ELIZABETH L. WURTZEL ‘89

In 1971, Dr. Preston K. Munter, associate director of the University Health Services, told the Crimson, “I think Harvard people had their adventure in drugs, and probably the message that enough people were harmed by drugs finally got through.” Seventeen years later, in the opening paragraph of her story about finals clubs, the paper’s music critic would prove him wrong:

I have drunk their liquor, snorted their cocaine, smoked their pot, popped their ecstasy, eaten their food and danced on their floors.

My alma mater, Boston University, gave me a semester’s probation for mere proximity to illicit drinking, so I’m dopily impressed by Wurtzel’s devil-may-care admission, and by Harvard, for declining to punish her for it.

Wurtzel’s work wasn’t always confessional; earlier clips were straight critiques of music, theater and movies. Please note her review of Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling, for its description of Richard Pryor as “looking like a bloody, beached alligator with an afro.”

JOHN C. YOO ‘89

Regrettably, it is almost impossible to read Yoo’s Crimson clips divorced from his view, given as an official of the Justice Department under George W. Bush, that a president may legally have a child’s testicles crushed. But one of Yoo’s last columns, headlined “Thank God for Hot Dogs,” is delightfully obsessive:

You start with a kosher-style hot dog, sitting plumply in a steamed poppy-seed bun. The hot dog is not really kosher, but is all-beef with just a hint of garlic — all enclosed in a natural casing. It should come from the Vienna Beef Company of Chicago, if you are a hot dog purist.

Surround that with — yes, it’s true — pickle relish, yellow mustard, a few chopped raw onions, a slice of tomato, a deli-style pickle and some nice burning jalapeno peppers, and you’ve got your dog. Chicago Frank’s offers the dog for only $2.25, and if you use the $1 off coupons being distributed, that works out to the same price as five pinball games (for those of you figuring out opportunity costs). Also included are a handful of fries, hand-cut on the premises with the skin still on the ends, that make a mockery of the frozen icicles usually served in the Square.

I sent Yoo a late-night note asking what prompted the column. He replied: “Mr. Green: Anyone who claims they remember why they wrote a college newspaper story, or that they even wrote such a story, either has too little to do or is lying.”

CURIOS

• An April 26, 1973 announcement of a concert in Kirkland House: “Mozart and Bartok quartets and the Schubert string quintet. James Buswell and Annie Kavafian, violins; Yo-Yo Ma and Madeline Foley, cellos; and Marcus Thompson, viola. Tickets: $1 with Harvard I.D. April 27, 8:30 p.m.”

• Arguably the most wonderful joint byline in journalism history; David Halberstam would win a Pulitzer in 1964, J. Anthony Lukas would win his first in 1968.

• A 2005 profile of Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg. “’I need servers just as much as I need food,’ says Zuckerberg. ‘I could probably go a while without eating, but if we don’t have enough servers then the site is screwed.’”

1 From Lemann: “No, that’s not true. The entire executive board of the Crimson elects

the next president, and the vote is secret. I cast my vote based on whom I thought would make the better Crimson President, not on ideology.

Having said that, I am still in touch with Grover regularly and I consider him a friend. He just sees the world somewhat differently from the way I see it. Also, if Eric was a socialist then (which I don’t remember him being; as I also don’t remember Jim Cramer being anti-Zionist), he sure wasn’t one within a few years! He was editorial page editor of the NY Post when he died.”

Previously in series: What Famous People Smell Like

Elon Green is a contributing editor to Longform.

America Ends War On Innocent Southern California Sea Otters

A 25-year federal campaign against sea otters in Southern California is finally ending, because it turns out sea otters will go down the coast if they want to, because declaring the whole of Southern California from Point Conception to the Mexican border an “otter-free zone” just wasn’t a very good idea.

In 1987, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began a program of forced otter relocation, capturing the endangered animals whenever they strayed into the Santa Barbara channel. Why? Because the U.S. Navy and the commercial fishing industry objected to an earlier plan to establish a backup population of the endangered sea mammals on San Nichols Island, the most remote of the Channel Islands. The Navy likes to kill marine mammals with weird sonar weapons, and the fishermen didn’t want the otters getting all the shellfish — the otter’s federally protected status angered the sea-war and sea-fishing industries, so somebody in Washington signed a piece of paper that said otters couldn’t leave their Northern California sanctuary.

“Trying to tell a marine mammal to stay on one side of an imaginary line across the water was a dumb idea,” said Steve Shimek, executive director of The Otter Project. The change in policy “will not only protect sea otters from harm, but because of the otters’ critical role in the environment, it will also help restore our local ocean ecosystem.”

Otters can migrate into the waters of Southern California without threat of being caught and returned to Northern California.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service quit relocating the otters in 2001, but the SoCal animals had no protection as an endangered species. Now, the furry friends will be afforded the same status as their elite Northern California sisters and brothers. Conservation groups sued the federal government in 2009 to win protection for the otters statewide.

Less than 2,800 sea otters remain on the California coast. Before they were hunted to near extinction, some 16,000 happy waving otters lived in the Pacific Ocean between the Oregon border and Mexico. Also, otter couples hold hands when they sleep, so their mates don’t float away. Otters are so much better than people!

Photo by Mike Baird.

87-Year-Old Man Wedges Car Into Bike Lane On Way To DMV

Here is how not to use a bicycle lane: An 87-year-old Marin County man was driving to the Department of Motor Vehicles office when he mistook a narrow concrete-walled bicycle-pedestrian path for Highway 101, and then he just kept driving until his car was wedged so tightly between the cement barriers that a tow truck had to yank the Toyota out. Is this symbolic of the increasingly hostile urban turf wars between automobile drivers and bicyclists?

Maybe! Listen to what this guy said, after all the trouble he caused: “They should block that off, that passageway.”

Raymond Pierce will have a mandatory re-evaluation of his driving privileges, under California law. There were no injuries to people, but the bike lane and the old man’s pride both suffered terribly.

Photo by California Highway Patrol, Marin County.

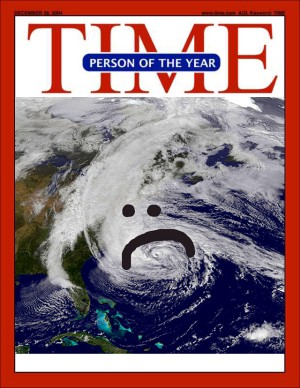

Barack Obama Is Okay, But Superstorm Sandy Is The "Person Of The Year"

Aren’t there any other black presidents who win historic elections against old white rich guys? No? Well then, Barack Obama is the Person of the Year, according to TIME, which is not even trying anymore now that Newsweek is gone. Obama was chosen because, let’s see, “We are in the midst of historic cultural and demographic changes, and Barack Obama is both the symbol and in some ways the architect of this new America. In 2012, he found and forged a new majority, turned weakness into opportunity and sought, amid great adversity, to create a more perfect union.”

If taking our guns away and taxing the Koch Brothers at a 99% federal rate and “solving the ocean” makes for a more perfect union, we … well, we’re pretty much good with all that! But “Superstorm Sandy” was obviously the Person of the Year. Obama is a historical marker for historical demographic shifts and the end of a certain kind of corporate-funded hate-filled “populism” that will hopefully die with the elderly white human grudges who kept it going since the Reagan era. But Sandy was more than that. How much more depends on how severe climate change already is, how fast it’s accelerating, and how quickly we can finally get it together to properly manage and maintain the only known habitable planet within 24 trillion miles. That’s a long way, right, Obama?

Congratulations, Sandy! You are The Awl’s “Person of the Year.”