Your Snow Angel Will Not Be As Good As The One A Great Horned Owl Left After Scooping Its Prey From...

Your Snow Angel Will Not Be As Good As The One A Great Horned Owl Left After Scooping Its Prey From The Ontarian Tundra

A couple of Christmases ago, I was in upstate New York with family and friends and it snowed like two feet. We took my kid outside to play and we built a snow man and a snow fort. My in-laws’ best friends are a couple named Roberta and Viki. Roberta is an art historian. Viki is a museum director. They both have strong opinions and they joined us outside, where Viki found a patch of deep powder and let herself fall backwards into it to make a snow angel. She did the jumping-jacks move like you’re supposed to do and got up to admire her work. “There!” she said. “What do you think?”

We all applauded her. But then then, hesitatingly, Roberta noted a problem.

“Hmm,” she tilted her head and looked at the print Viki had left in the snow. “I don’ think you were doing it right.”

“Excuse me?!” said Viki, mock-enraged. (And maybe a little bit honestly enraged, too.) “Are you actually critiquing my snow angel technique?”

“Well…” We were all laughing by now, and Roberta, too. But she defended her position. “You raised your arms too high above your head, you’re only supposed to go up so far. Your hands aren’t supposed to meet.”

Sure enough, Viki had brought her arms all the way up, executed full jumping jacks, instead of stopping at shoulder height.

“Well, that’s how I learned to do it! Those are the wings!”

“Yes, but you can’t see the head, or, really the wings, either, because it’s just a big bell shape atop the torso.”

An argument ensued, one that drew in a wide array of spectator commentary and continued inside, over lunch, for a long time. It is one of my favorite things that has ever happened.

With eternal apologies to Viki, I have to agree with Roberta’s complaint. The head of a snow angel should be visible, with the wings extending as two distinct isosceles triangles. The decision to voice such an opinion after one’s partner has just displayed a work of public art is another matter. And one which I leave to the vagaries of individual couples and each specific situation.

Either way, though, I know one for sure: No human being will EVER make as beautiful a snow angel as this great horned owl did recently in Timiskaming, Ontario. LOOK AT THIS PICTURE!

Photo by Arsentyeva E, via Shutterstock

What Made "The O.C." Great, Bitch

What Made “The O.C.” Great, Bitch

by Jia Tolentino and Mallory Ortberg

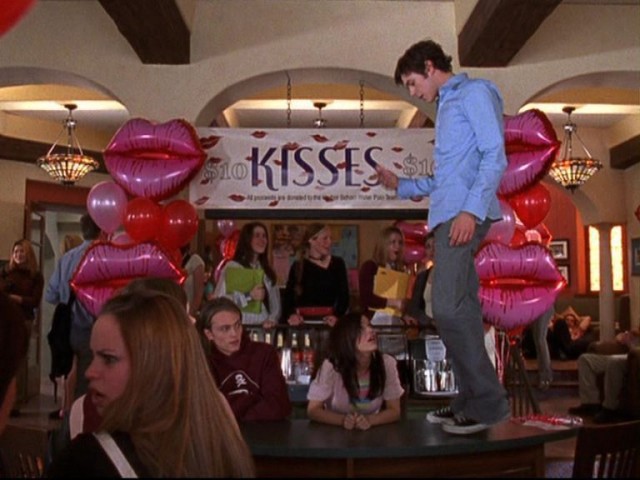

“Welcome to the O.C., bitch.”

— Luke, “The O.C.,” Season 1, Episode 1

Sometimes disorder introduces itself into long-standing order. Such is the plot of almost everything compelling: “Downton Abbey,” the evolution of the norovirus, “The Nanny,” bedbugs, “Jurassic Park,” civil rights, the lineup changes of Foreigner, infidelity. So goes, also, the story of Ryan Atwood, who storms Newport’s gated communities with little more than a hoodie, a wrist cuff, a pack of Marlboros and his trademark Chino flair in the pilot episode of “The O.C.”

This essay is part of a series about our favorite TV shows past.

Previously: The Joys And Derangement Of “F Troop”

We, perhaps you, and millions of other people of a certain emotional archetype were devoted to “The O.C.” We huddled in front of the TV on Tuesday nights with bottles of Boone’s Farm and a near-religious fervor. We gasped when Ryan carried Marissa’s prone body through the streets of Tijuana (“Tee-hauna,” Seth would clarify). We have the orange-and-blue DVD box sets and we will never throw them away no matter how impractical DVDs become. We have described our relationship with the show’s first season as both “incredibly, unhealthily obsessive” and also “the best I’ve ever had.”

“It’s personal in the deepest possible way,” said Ira Glass of his weekly ritual surrounding “The O.C.” “I’m 47 years old. I’m a grown-ass man, you know? We’re a married couple. Sober. We are sober, singing the theme to a FOX show. And I have got to say, every single week it makes me love my wife, and love TV, and love everything in the world all at once. And last week, when ‘The O.C.’ went off TV, I cried. And I’m not ashamed to admit it.”

The show’s fanbase watched so attentively that, years later, IMDB still lists continuity errors like “When Haley is seen at the club dancing, her hair is curled. When she’s leaving the club her hair is straightened” (Season 1, Episode 22, “The L.A.”). At UC Berkeley, Peter Gallagher’s role on the show has been immortalized by the Sandy Cohen Public Defender Fellowship, which supports law students working in the Orange County public defender’s office. This is something that exists in real life.

A decade after its first season originally aired, “The O.C.” seems both prescient and profoundly of its era. In some ways it’s a time capsule of American culture in 2003 — Paris Hilton appears as a not-exactly-ironic-but-decidedly-self-referential UCLA-attending version of herself who begs Seth: “Don’t tell anyone I’m a grad student, okay?” — but in other ways, the show was groundbreaking. It was the first show to capitalize on the growing popular appetite for indie music, an early champion of nerd culture as default, the first teen soap to be explicitly self-aware. It had a parody of itself (the TV show “The Valley”) nested within its universe. The show prompted a resurgence of a golden, West Coast exceptionalist fantasy whose pop-culture descendants have been both regrettable (“The Real Housewives,” “The Hills”) and terrific (SNL’s “The Californians,” The Lonely Island’s “The Bu”).

***

For those who have never seen “The O.C.”: a word.

The ostensible protagonist was Ryan Atwood, a brooding Russell Crowe-lookalike who, when the series begins, is in jail, sitting down with a giant-eyebrowed public defender named Sandy Cohen. Sandy was married to workaholic ice queen Kirsten, whose father Caleb is a real estate mogul who “owns half of Newport.” The Cohens’ teenage son Seth — picture a young, male, Jewish Liz Lemon, who acts as an audience stand-in and is the real star of the show — becomes Ryan’s best friend and confidante when the Cohens decide to install Ryan in their pool house, giving him a shot at a better life.

What this better life looks like for Ryan: a beautiful blonde named Marissa Cooper, the girl next door with sad deer-eyes and prominent collarbones. Marissa’s best friend Summer, a travel-sized brunette, has for years been the object of Seth’s lifelong unrequited love. Marissa is a secret populist and budding substance abuser whose father is about to commit Madoff-style fraud. Marissa’s mother wears Juicy tracksuits and acts as a fierce guardian of her own class anxiety and across-the-tracks background. Marissa’s boyfriend Luke is an evil lacrosse stick dipped in grain alcohol (the grain alcohol is also evil).

These ten characters, spanning three generations, meet in six different romantic combinations within the first season. The pilot episode of the show alone covers grand theft auto, cocaine, juvie, white-collar fraud, a seven-figure wealth gap, a threesome in the bathroom of a high school party, brawling, infidelity, alcoholism. Yet the great trick of the show is that it doesn’t feel like all that. It feels private, like a diary. It took melodrama and removed the self-importance. It used its carefully engineered exterior of beauty, wealth and scandal to sneak in an interior that was all depth and familiarity and heart.

***

The appeal of “The O.C.” begins (and for some, ends) with the official soundtrack, a billion-footed indie beast that Josh Schwartz, the show’s creator, set out to make into a character in its own right. Episodes were often soundtracked before they were scripted. Up-and-coming artists premiered their new songs on “The O.C.” and often performed on the show’s concert venue The Bait Shop. The audience in turn paid close attention to who was on the roster; when one episode featured the U2 single “Sometimes You Can’t Make It On Your Own,” the reaction was fierce. “Selling out,” wrote an Entertainment Weekly columnist, presumably with a straight face. Musically, the show had pulled off a gambit that has since become commonplace; the soundtrack was nominally indie but undeniably popular — stylized and edgy enough for viewers to feel addressed as unique individuals, but approachable and mainstream enough to draw the crowds.

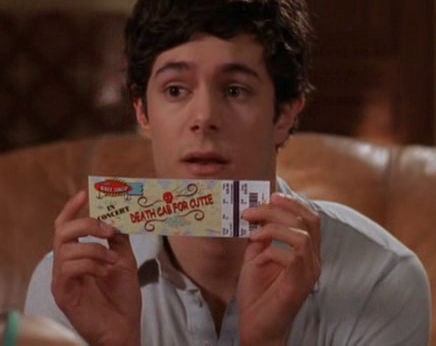

If you compare the music of “The O.C.” to other shows of its era, it starts to seem even more remarkable. “Dawson’s Creek” ended the same year that “The O.C.” began, but the two seem generations apart. Dawson’s was all plunky guitar and Alanis Morissette playing over soft-focus, flannel-ridden montages. The same year, “The O.C.” featured Röyksopp, LCD Soundsystem, The Pixies, and Tunng, as well as many artists that defined the wave of gloriously sincere early-2000s indie chart-toppers: Feist, Death Cab for Cutie, Wilco, Sufjan Stevens.

Indie-as-middlebrow is standard today, and the “The O.C.” doubtlessly played a part in this model’s genesis. Were it not for the show, Stephenie Meyer — the most visible force of lowest-common-denominator culture in recent memory — might not now be urging her blog readers to listen to Grizzly Bear and Animal Collective.

***

“The O.C.” drew heavily on one of the most important soap opera conventions: that of erasure, where consequences are few and often impermanent. In the first season of the show, Julie Cooper appears to be happily married, a picture-perfect trophy wife. But by the fifth episode, Julie has filed for divorce; by the tenth, she’s dating Kirsten’s father. Then, in episode 19, she begins an affair with Luke, her daughter’s ex-boyfriend. A few episodes later, Luke is gone and Julie’s back with Caleb; the season closes on their wedding and a “Hallelujah” cover.

Luke, who resembled nothing more than a poor man’s Casper Van Dien, spent the first season undergoing more character rewrites than anyone else in television history. In the pilot he is a featureless goon in a puka shell necklace, the empty swagger of Newport Beach writ large (“Welcome to the O.C., bitch” is quite rightly the most memorable line from the show, even though Luke is one of its least memorable characters). By the end of episode two, he has displayed a glimmer of self-reflection and at least attempted to save Ryan from a burning model home. By episode seven, he is an unfaithful sociopath, whose public infidelity is largely responsible for Marissa’s overdose. From there he confronts his own homophobia after learning his father is gay and in love with another man, sleeps with Marissa’s mother Julie, saves Marissa from the wily Oliver, repairs his friendship with the gang, and picks up a guitar and starts dispensing soulful advice. He closes his character arc with perfect equanimity, joking that he’ll fall in love with a Portland girl and have to fight her football-captain boyfriend, and will end up on the receiving end of a sucker punch and a “Welcome to Portland, bitch.” What other teen drama displayed such self-awareness?

Luke pulls off the ultimate teen dream of self-transformation: he remakes his identity easily and totally, whenever it suits his needs. In the early days of the series, Luke could not make it through a school day without hitting someone; by the time he decamps for Portland, friendly Gay Dad in tow, he practically presses his palms together and murmurs “namaste” at every goodbye. Everything in the world happens to Luke. Nothing does not happen to him. He contains multitudes.

***

The syllabus for Duke University’s course on “The O.C.”, titled “California Here We Come: The O.C. and the Self-Aware Culture of 21st-Century America,” begins with a quote from Schwartz: “Everybody is hyper self-aware. We live in a post-everything universe.”

This “hyper self-awareness” may be what “The O.C.” was best at, its desire to stay one ironic step ahead of everything communicated most clearly through one character, the (as described on the Duke syllabus) “nerdy, comic-book reading, plastic-horse-loving, half-Jewish sailor with a keen taste in music named Seth Ezekiel Cohen.” With his comic books and Michael Chabon novels in hand, Seth was the reliable, deflationary voice of reason. “You’re a Cohen now. Welcome to a life of insecurity and paralyzing self-doubt,” he says to Ryan early in the first season. Throughout the show, he does not become more like the other characters, but they become like him, even adopting his hyper-fast and ultra-quirky speech patterns.

Everything that could be criticized about “The O.C.” was addressed outright on the show. Benjamin McKenzie, the actor who played Ryan, was frequently called out for looking much older than a teenager; in one episode, Ryan sees the actor who plays his equivalent on a teen soap called “The Valley,” and asks, “How does that guy play a high schooler?” Seth sighs. “Hollywood,” he says.

As the show progressed, the characters continued voicing their own audience. “I wish I was from the Valley,” whines Summer in one episode. “Ugh, they’re playing Death Cab on ‘The Valley’?” says Marissa’s little sister, Kaitlin, in another. “I’m never listening to them again.”

The show even addressed its own impending decline in the first holiday episode. “What if it’s starting,” asks a worried Seth. “The Chrismukkah backlash. What if it’s getting too big and commercial. Dude, I knew this would happen, it’s like it starts out as this really cool cult holiday, you know, flying beneath the cultural radar, then suddenly it crosses over and there’s too much pressure.”

In the second season, Marissa embarked on a short-lived lesbian relationship with rebellious club manager Alex Kelly (played by popular fictional lesbian Olivia Wilde) during Sweeps Week. “Hey listen, Alex,” Seth tells her when he realizes the two of them are dating. “Thank you. Both of you. For everything. I mean, keep doing what you’re doing. I like it.”

***

No other show ascended as high or crashed as hard as “The O.C.” When it started airing, it had the highest ratings among 18- to 34-year-olds of any drama on television. The first season was incandescent; the second was wildly uneven (the arrival of Caleb’s secret daughter,Kirsten’s alcoholism, Marissa’s poolside meltdown). But the rest of the show was abysmal and heartless — quick shouts to Taylor Townsend and Trailer Park Julie Cooper, though — and by the time it went off the air in 2007, it had been abandoned by nearly all of its former fanatics.

So what happened? Maybe “The O.C.” exhausted the big formulas too quickly; in the classical models of comedy and tragedy, the first season ended with a wedding and the second with a death. Maybe, as with “Gossip Girl,” it became impossible for the writers to maintain depth for too long in a setting that was defined by its superficiality. Maybe, as with “Downton Abbey,” the initial plot — the outsider becoming the insider, winning hearts, establishing a new and better order — was the only one that carried real urgency.

But probably the real answer is that the show just lost its heart. It happens to most shows. It happens to most things. The relationship a certain kind of young person had with “The O.C.” while it lasted was exactly like most of our first relationships, full stop: obsessive, full-throated, and often unrequited. It didn’t matter whether your ardor was returned; that person that inspired spirals of conjecture, song lyrics mapped out painstakingly to every twist and turn of behavior. The person was everything, but once you parted ways, you never thought about him or her again.

Previously: The Joys And Derangement Of “F-Troop”

Jia Tolentino lives in Ann Arbor. Mallory Ortberg is a writer in the Bay Area. Her work has also appeared on The Hairpin, Slacktory and Ecosalon.

Why Aren't You Using These Hot New Apps To Keep Track Of Your Impending Death?

Everybody loves apps, experts say — you can tell because there is an app for everything, including the monitoring of your personal health. The problem is that once you’re thinking about monitoring your personal health, you’re well on the way to the grave. This depressing fact may be the reason why few Americans use such phone and tablet programs to keep track of what’s all too evident from the creaking, coughing, groaning and “weird discharge” most people notice just fine without the danged smart phone beeping and whirring, from wherever it’s hiding.

Nearly seven in 10 U.S. adults say they are tracking weight, diet, exercise routines or some medical symptom for themselves or a loved one, but most are doing it without the aid of modern technology and many are just keeping track in their heads, a new survey finds. The findings may “splash some cold water” on the idea that the masses are tracking and analyzing everything from their daily step counts to their sleep patterns and blood pressure on their smart phones, tablets and computers.

Ha ha, “splash some cold water” is one of those mainstream media euphemisms for suicide. Also many people who are close to death are, by nature, older people. And older people generally don’t like those complicated smart phones and tablets and computers. They prefer to have those very big “clamshell” phones with very big numbers, and then they always leave these phones turned off, because they are worried about the battery running out, and also they have suspicions that maybe the phone is “calling long distance” while nobody is watching it.

Photo by Voronin76 via Shutterstock.

Big -- And Little-Changes at 'The New Republic,' Which Is a Magazine

In a dramatic move under new tiny millionaire owner Chris Hughes, The New Republic has redesigned its website to take a strong stand against em dashes. Simply everyone is talking about it: sometimes presented as two adjacent hyphens, sometimes replaced by a misused en dash, but always using a type treatment that shortens both em and en dashes, perhaps related to the use of double-justified text, this typography is both innovative and disruptive. As is its daringly large linespacing. Also they eliminated advertising.

Enemy Monkey Launched Into Space By Iran

Longtime American enemy Iran made another bold move in its passive-aggressive hostilities toward Washington by … let’s see, by reportedly sending a monkey into space. Who would do such a thing, to a monkey?

Press TV, the state-run satellite broadcaster, said the animal was launched in a space capsule code named Pishgam, or Pioneer. The development coincided with continued stalemate in the unrelated Western effort to persuade Iran to abandon its nuclear enrichment program, which Western powers maintain is designed to create nuclear weapons technology — an assertion Iran denies.

So, sending this animal into orbit for a moment “coincided” with the “unrelated” 35-year problems Iran has with its former imperial overlords in Washington. But unlike our former worst enemies, the treacherous Soviets, Iranian scientists claim to have retrieved this abused animal alive after its terrifying adventure 75 miles above Earth. Also, it is sneaky of our worst enemies to use their secret language to call the monkey rocket “Pioneer,” which is a patriotic American word from the U.S. space program. Enjoy the monkey’s “selfie” on Vine!

Things To Read, 102 Of Them

You know what? I don’t want to hear you say “I’ve got nothing to read” for a solid two weeks at least, okay?

Courtney Love, "99 Problems"

Would you like to watch Courtney Love playing an acoustic-guitar cover of Jay-Z’s “99 Problems” at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah this past weekend? She doesn’t do my favorite part, the third verse, when Jay-Z outsmarts the cop who pulls him over. But this is better than you might have imagined it would be.

Crescent City Penguins Unaffected By Disasters

“An article on Friday about a decision by the New Orleans Hornets to change the team’s name to the Pelicans misidentified, in some editions, the bird population in Louisiana that was threatened by Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. It was, of course, the pelican population — not the penguin population.”

Mondays, Am I Right

Rebecca Dana v. Emily Gould at BookCourt. (JK, there’s no “v.” about it.) Jonathan Coulton the musical guest at NPR’s “Ask Me Another” at the Bell House. Meanwhile: cold.

How Should We Pronounce That Name, 'New York Times' Obituary Writer Margalit Fox?

How Should We Pronounce That Name, ‘New York Times’ Obituary Writer Margalit Fox?

• From Shulamith Firestone’s obituary: “The family Americanized its surname to Firestone when Shulamith was a child; Ms. Firestone pronounced her first name shoo-LAH-mith but was familiarly known as Shuley or Shulie.”

• From Paul Roche’s obituary: “The author of several well-received volumes of poetry, Mr. Roche (pronounced ‘rawsh’) taught over the years at colleges and universities throughout the United States, among them Smith College; the University of Notre Dame; Centenary College in New Jersey; and Emory & Henry College in Virginia, where, his family said in a statement, ‘He used to wander stark naked through the woods carpeted with violets.’”

• From Giorgio Tozzi’s obituary: “At his death, Mr. Tozzi (pronounced ‘TOT-zee’) was a distinguished professor emeritus at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music, where he had taught since 1991.”

• From José Argüelles’s obituary: “Originally an art historian at Princeton and elsewhere, Mr. Argüelles (pronounced “ar-GWEY-es”) was known afterward for books like ‘The Mayan Factor: Path Beyond Technology’ and ‘Surfers of the Zuvuya: Tales of Interdimensional Travel.’”

• From Hugh Prather’s obituary: “An aspiring poet with a cache of rejection slips, Mr. Prather (pronounced PRAY-thur, with a soft ‘th’) sent the journal on impulse to a small publisher with limited distribution capabilities and no national advertising budget.”

• From Gitta Sereny’s obituary: “A resident of London who had lived most recently in Cambridge, Ms. Sereny (pronounced “suh-REE-nee”) was long considered one of the foremost investigative journalists in Britain.”

• From Huguette Clark’s obituary: “In the hospitals, Mrs. Clark, whose given name is pronounced hyoo-GETT, was attended by round-the-clock private aides and surrounded by the fine French dolls she had collected since she was a girl.”

• From Brent Grulke’s obituary: “Mr. Grulke (pronounced GRUHL-key) was South by Southwest’s creative director, a post he had held since 1994, when the festival presented some 500 bands.”

• From Beate Sirota Gordon’s obituary: “The daughter of Leo Sirota and the former Augustine Horenstein, Beate (pronounced bay-AH-tay) Sirota was born on Oct. 25, 1923, in Vienna, where her parents had settled.”

• From Else Holmelund Minarik’s obituary: “The first of many books by Ms. Minarik (pronounced MIN-uh-rick), ‘Little Bear’ appeared in 1957 as the inaugural title in the I Can Read! series.”

• From Arthur Lessac’s obituary: “Over the years, singers flocked to Mr. Lessac, whose name is pronounced LESS-ack, with saxlike accentuation of the first syllable.”

• From Antonio Tabucchi’s obituary: “Mr. Tabucchi (pronounced ta-BOO-kee), who was also a scholar of Portuguese literature, divided his time between Lisbon and Tuscany.”

• From Salvador Assael’s obituary: “Mr. Assael (pronounced ah-sigh-YELL) was known in particular for creating the modern market for black pearls, which had traditionally languished in the shadow of their brilliant white cousins.”

• From Linda Riss Pugach’s obituary: “In the years since, the strange romance of Mr. and Mrs. Pugach (pronounced POOH-gash) has seldom been far from public view.”

• From Gerre Hancock’s obituary: “(His given name is pronounced Jerry.)”

• From Keith W. Tantlinger’s obituary: “(The family name is pronounced TANT-lin-gurr, with a hard ‘g.’)”

• From Dino Anagnost’s obituary: “Mr. Anagnost (pronounced ANN-ug-nahst), who succeeded Mr. Scherman as music director in 1979, conducted the orchestra in more than a thousand public concerts, appearing at Avery Fisher Hall, Alice Tully Hall, Zankel Hall and elsewhere.”

• From Stephen Huneck’s obituary: “(The family name is pronounced HYOO-neck.)”

• From David Rakoff’s obituary: “For his incisive wit and keen eye for the preposterous, Mr. Rakoff (pronounced RACK-off) was often likened to the essayist David Sedaris, a mentor and close friend.”

• From Stanley H. Biber’s obituary: “A former Army surgeon, Dr. Biber (pronounced BYE-ber) was among the first doctors in the United States to perform sex changes and for years was one of only a handful to offer them.”

• From Sam Chwat’s obituary: “Mr. Chwat’s very surname foreordained him for the phonetical life: It is pronounced ‘schwa,’ like the vowel sound (‘uh’) symbolized in dictionaries by an upside-down-and-backward ‘e.’”

Previously by this writer: The Mystery Of The 1969 Naked ‘Esquire’ Photo Shoot

Elon Green is a contributing editor to Longform.