Today Is Very Cultured

Jessica Hagedorn appears! (With Jonathan Lethem.) A panel celebrates Mary MacLane at BookCourt. Low plays. Get yer Stockhausen tickets while you can! ALL THIS and more.

Five Reasons To Watch "The Lizzie Bennet Diaries"

Five Reasons To Watch “The Lizzie Bennet Diaries”

by Janet Potter

Next Thursday, March 28th, I’ll be sad to see “The Lizzie Bennet Diaries,” a brilliant web series that adapts Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice to a modern-day California setting, come to a close with its 100th episode. Created by Hank Green and Bernie Su, both prolific producers of web-specific content, this series has, lamentably, reached the end of its source material.

Its premise is that Lizzie Bennet, a 24-year-old graduate student in mass communications, starts a video blog as a school project. Providentially, she starts this vlog just as rich med student Bing Lee moves to the neighborhood and starts macking on her sister, and everyone’s lives go bananas. Since April 2012, two episodes of the “Diaries” have been uploaded per week, in between which the characters are active on social media, such as Jane Bennet’s Pinterest boards and Mr. Darcy’s Twitter account.

I got on board earlier this year, after idly (and skeptically) clicking on the first episode. Then I caught up in three marathon viewings, and now the days that the new episodes go up are high points of my week. There is something about Pride & Prejudice that makes me love having the story told to me over and over again. From the number of times I’ve read the book or watched the BBC and movie adaptations, the plot no longer holds any surprises, and yet the suspense is always there. “The Diaries” retains the tartness and romance of Austen’s original story, even when Bingley’s name is Bing Lee, nobody is wearing bonnets, and Kitty Bennet is an actual cat. Now that you can watch the series from start to finish, here are some reasons why you should.

1. BENNET SISTER GIRL POWER

In Austen’s time, five sisters spending their days together was commonplace, but transplanted into a modern context, the genuinely close relationship of the Bennet sisters gives the series its refreshing, endearing center. The series demotes Mary and Kitty to cousin and feline status, respectively, and the Bennet parents are never seen, leaving us in the able hands of Jane (Laura Spencer), Lizzie (Ashley Clements) and Lydia (Mary Kate Wiles). All three are in their 20s and still live at home: Jane is underemployed, Lizzie is in grad school, and Lydia is an undergrad. Jane and Lydia regularly pop in to Lizzie’s videos to help her relate what’s been going on in their lives or, more frequently, to discuss whichever sister is not present. They are unflagging advocates for each other’s happiness, a fact which becomes especially striking after The Incident of Lydia’s Disgrace, and it makes you realize how much the loyalty and support the Bennets give each other is at the core of Austen’s novel. (And they’re all redheads!)

2. LYDIA BENNET: NOW LESS VEXING!

Although I’ve always loved to hate Lydia Bennet, this is the first time I’ve flat-out loved her. In Green and Su’s adaptation, her blind exuberance and zeal for flirting are simply the result of her moxie taken to its extreme. It doesn’t represent the totality of her personality: she is also perceptive, adventurous, and loyal. Watching Mary Kate Wiles juggle these contradictions, all the while making mischievous side-eyes at the camera, is an unending treat. Particularly after The Incident, her portrayal of a chastened party girl reviewing her life choices is complicated and compelling, with hints that her inner spitfire will soon surge back. For the first time I’m rooting for Lydia instead of rooting for her to be shoved off a bridge somewhere. (When Lizzie is away from home for extended periods, visiting Netherfield or with her friend Charlotte, Lydia maintains her own spin-off vlog, also produced by Green and Su, and this is great.)

3. AN A+ DARCY

My heavens, this dreamboat. Because of Lizzie’s original antipathy for him, Darcy doesn’t appear for the first seven months of the “Diaries,” he’s just mentioned as an odious person to see at a party. Wondering when he’ll turn up, and how he’ll live up to the role of one of the most crushed-upon men in the history of fiction was a tall order for Daniel Gordh, but he manages to be true to the character as Austen wrote him and to make Darcy seem unique to this adaptation. Granted, the alchemy of Austen’s story is such that if Pride & Prejudice was staged as a sock-puppet show I’d probably develop a crush on the argyle Darcy. But Gordh hits a perfect mark between gentlemanly reserve and simmering emotion — I could watch him sit uncomfortably in a chair for the rest of my life.

4. THE PLEASURES OF ANTICIPATION

Many of us, if I can presume I’m representative of a demographic, have Pride & Prejudice memorized scene-by-scene. It’s great fun to know what points of the story are coming up, and waiting to see how they’re updated. Is Mr. Collins really going to propose to two best friends within a week of each other? What will be the history between Darcy and Wickham? How will Lydia disgrace her family? What’s ailing Anne de Bourgh? How will Mrs. Bennet connive to have Jane stay at Bing’s house? Will Bing, Darcy, and Wickham have jobs? Will Lizzie take a turn about the room with Caroline? Will it be refreshing?

5. EVEN WHAT’S BAD IS GOOD

Because the series’ conceit is that Lizzie is vlogging on a laptop, the only way to incorporate other characters is to have them join her in front of it. Have you ever been sitting at your desk when someone drops by to chat, and instead of you getting up, they sit down beside you at your desk and you talk to each other sideways. No? Neither has anyone else in the history of time, but so we can watch, this is how Lizzie has 98% of her conversations. Sometimes she and her interlocutor are purposely recording their conversation for the vlog, hence the strange seating arrangements. Other times, notably the first handful of times we meet Bing or Caroline Lee, they simply find Lizzie sitting at her computer and join her there for bizarrely revelatory dialogue.

These shoulder-to-shoulder conversations can be distractingly implausible. What would be worse, however, is if the series only showed conversations that Lizzie would realistically record for a vlog, thereby preventing us from ever seeing Bing or Darcy. That, as alluded to above, would be a grave misfortune. And while the series pushes the limits of encounters that would naturally happen at a desk, there are many other scenes that this particular format can’t capture, no matter the contrivance involved. Lizzie and Darcy’s first dance, Lydia making a spectacle of herself at parties, and Mrs. Bennet’s flair for the ridiculous are all beloved elements of the book that are presented secondhand in the series.

Every storytelling medium has its limitations, and many of this series’ machinations to overcome them have long been present in the theater (as anyone who’s had a school play director bellow “face the audience!” at them during every rehearsal can attest). By choosing to adapt such a familiar story, the series’ creators are allowing you to notice these limitations at each turn. You’re not just watching them recreate Pride and Prejudice, you’re watching as they problem-solve their way out of the constraints of the format they’ve chosen. Sure, it may have been easier to adapt a story in which less pivotal action took place at public dances that they can’t show, but it may also have been boring. Watching Green and Su take on a story that stretches the capabilities of a new storytelling genre is both a primer for that genre and a testament to their ingenuity.

But technical and creative accomplishments aside, Lizzie and Darcy are about to have their first kiss for the 8 millionth time in history, and you should be there.

You might also enjoy: ‘The Secret History’: I Know What You Did Last Reading Period

Janet Potter is a staff writer for The Millions and blogs about presidential biographies at At Times Dull. Follow her @sojanetpotter.

New York City, March 18, 2013

★★★★ The wind blasted right through a sweater on the way out the door. Heavy-coated toddlers, roped together, caterpillared their way down the block. There had been clear orange light at dawn, but now there was no sign such a thing had ever been possible. The buildings on Fifth Avenue framed solidly gray sky. Down inside the 23rd Street station, cold air plummeted through the sidewalk grate, bounced off the ceiling covering the tracks, and poured down the back wall of the platform. By afternoon, dense, fine snow was angling down — and then there were white ice pellets, stinging, dropping straight. Chinatown grocers pulled plastic covers over their sidewalk bins. This was amounting to something; it was here for the duration. The pellets clung to cloth coats, taking a long time to melt even in the crowded subway station. In the evening, through a nauseated daze and under bedcovers, there came the sound of plows scraping pavement and behind that what seemed to be thunder.

Are You Still Waiting For Iraq War Apologies?

“I’m waiting to hear the words ‘I was wrong’ from some of the world’s most elite journalists…”

— People are still harping on that Iraq war thing, which was like more than 5 iPhones ago. Can’t we just Move On?

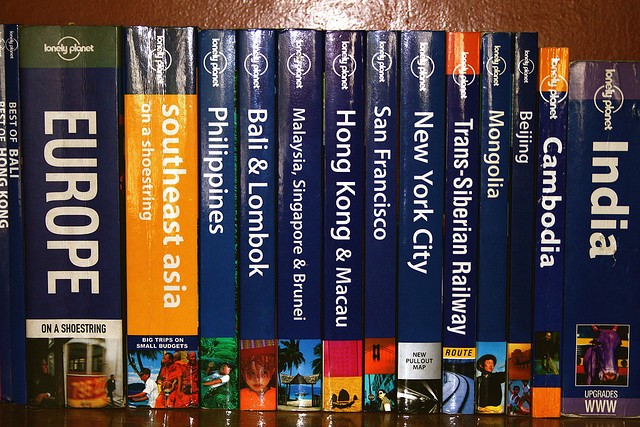

Lonely Planet Travel Guides Dumped At "Big Loss" By BBC

Chances are you have at least a couple of Lonely Planet guides on your bookshelves, or in a box in your parents’ garage along with very thin tax returns from the 1990s or early 2000s. I still have a couple of very outdated books — not for the informational value today, which is minimal, but because they’re time capsules of how those countries were when I was traveling around years ago. And now BBC, which has owned the independent travel guide since 2007, is selling the brand at a big loss to some American billionaire who may also have fond memories of the densely packed books.

The books still sell pretty well, with Lonely Planet being the best-selling travel guide in the UK, but BBC says it doesn’t want anything to do with the nice company and “would not make this sort of acquisition again.” But I’m probably not the only person who quit buying guide books around the time wifi became common, and now thinks a laptop is too much trouble to carry around.

Photo by The Wandering Angel.

Sex And Lies! The Iffy Science Of Measuring Calories

Sex And Lies! The Iffy Science Of Measuring Calories

by Trevor Butterworth

As you may have heard, sex doesn’t burn nearly as many calories as you might have been led to believe. But this is far from the only finding in obesity research that wilts under intense scrutiny, as the rest of this paper in the New England Journal of Medicine revealed. Each piece of received wisdom about weight-loss and dieting the study took on (eat fruits and vegetables! eat breakfast! etc.) — was found wanting. Conclusions: “False and scientifically unsupported beliefs about obesity are pervasive in both scientific literature and the popular press.” What we think of as hard science can, it turns out, be pretty soft.

One example as to why this is: Measuring the energy expended during sex turns out to be a Himalayan ascent of such ferocious complexity that even a seasoned alpinist might be reduced to wild surmise. As the study’s lead author, David Allison, who is the director of the Nutrition Obesity Research Center explained, “You don’t need to know anything about metabolism to know that someone would have to measure people having sex. And knowing that you’d say, ‘well, it’s probably not the same for a 20-year-old man versus an 80-year-old man; and it might not be the same for a man or a woman; and it might not be the same if it’s the same person you’ve been married to for 20 years or a brand new person.’ So all these factors may come into play and, of course, there may be quite individual variability from person to person.”

A study aiming to figure out the energy expended during sex would, therefore, need to have a large sample of people, representing all ages and both sexes — new lovers, people bored with their partners — just to capture a representative range of all possible energy expenditures. And once this sea of flesh was found, you’d have to measure the amount of oxygen they consume and the amount of C02 they expire, which requires a filtered, airtight room capable of monitoring these changes. Think about what doing that study would involve: hundreds of people willing to get it on in a submarine-like room in a university lab being monitored by academics. And then there are all the parameters: who and what goes where and when?

“Who’s going to volunteer for this study?” asked Allison. “And if they know they’re being watched by some investigators,” he added, “might this affect performance?” Ack; it might indeed: does inhibition subdue the heart or does voyeurism quicken it? A study that accounted for all this variability and answered all these questions with sufficient scientific rigor would surely be legendary, notorious, epic; but Allison and his coauthors could find nothing in the medical literature.

Still, where there’s a will, there’s usually a second best way of measuring something. In this case, you can put on a mask with a breathing tube attached to a metabolic cart, and have your oxygen intake measured during activity. This presents researchers and putative lovers with another potentially confounding problem: “Is someone having sex with a rubber face mask and a tube in their mouth the same as sex in ordinary circumstances?” asks Allison. “And again, who would volunteer for that?”

“Who’s going to volunteer for this study?” asked Allison. “And if they know they’re being watched by some investigators,” he added, “might this affect performance?”

It turns out that in 1984 ten married couples volunteered for precisely this kind of study, although only the energy expended by the men was measured. The study was trying to assess the cardiac demands of sex against a background where men who had recovered from heart attacks were reluctant to exert themselves in bed in case they killed themselves. The 10 male volunteers ranged in age from 25 to 43 and — worth noting — the average physical fitness was high. Small though the sample size was, the researchers were, gratifyingly, thorough. They began by measuring foreplay, although they conceded that the breathing mask made oral stimulation challenging, and the electrodes and blood pressure cuffs constrained movement; nevertheless, there was a small but statistically significant increase in heart rate by four to eight beats per minute. The biggest bang, so to speak, in terms of energy expenditure, was when the man was on top of the woman, although it varied; some men had more energetic orgasms than others.

Even here, as Steven Heymsfield, one of Allison’s co-authors, explains, the data they needed required translation. As best as can be determined, the average bonk burns no more energy than you’d expend walking briskly for about four minutes. This contrasts with the 30 minutes to an hour’s brisk walking everyone had assumed (21 versus 150–300 kilocalories).

That’s quite a come down.

AFTER SEX, THEN BREAKFAST.

Naturally, the finding grabbed the media by its news instincts. Somewhat lost in the excitement was the bigger picture: if measuring the energy expended in just six minutes was this difficult (yes, that was about the average amount of time the couples spent getting it on), how would you scale a lifetime of dynamic metabolic change? How would you measure the progress of obesity-related disease through thousands of constant — but not necessarily consistent — energy inputs and outputs and then adjust for genetic inheritance and age? Sex, says, Allison was simply an “intellectually useful” way to get people to think about the kinds of claims we just assume to be true, because we assume they have been measured accurately; there were bigger and more intellectually important targets to question: there was, for instance, breakfast.

Now eating breakfast has been shown to provide clear cognitive benefits for school children; but skipping it did not, Allison said, appear to leave you at the mercy of weight gain from over compensating with extra calories later in the day. Or rather, there was no solid evidence either way; it was just one of those things that everybody presumed was true without asking whether it had been shown to be true.

There was breastfeeding. Again, there is nothing wrong with breastfeeding — as, Allison is quick to emphasize, it’s highly recommended. But according to the best-conducted and most careful studies we have, it’s just not protective against obesity, as people have claimed for almost a century. Fruits and vegetables? Great — please eat; but don’t do so under the apprehension that they will produce weight loss in the absence of any other changes in diet and behavior. Snacking? Not quite the sneaky culprit of weight gain we have been led to believe — at least according to the data we have. Setting reasonable goals for weight loss? Meh — you might as well try to lose as much as possible as quickly as possible because it could work for you. On it goes, and due to the editorial limitations of the New England Journal of Medicine, they’ve started with the highlight reel; a much longer paper will be published later in the year.

Even so, the scale of the debunking led some to speculate that a conspiracy might be afoot, given Allison’s extensive previous funding from the food industry (his nutrition research center at the University of Alabama also, it should be noted, receives extensive funding from the National Institutes of Health). “It raises questions about what the purpose of this paper is,” Marion Nestle, a professor of nutrition and food studies at New York University and a highly vocal critic of the food industry and industry-funded science, told the Associated Press. On NBC, she said, “I can’t understand the point of the paper unless it’s to say that the only things that work are drugs, bariatric surgery, and meal replacements, all of which are made by companies with financial ties to the authors.” A mostly conjectural discussion about money, motive, bias, and why the paper’s authors might have covered some myths and not others followed on Health News Review.

“The point of our article was that evidence matters,” Allison told me. “If someone disagrees with one or more of our conclusions, let them state the evidence that supports their disagreement. In science, three things matter: The data; the methods by which the data were collected, which define them and provide their validity or ‘knowledge value;’ and the logic by which the data are connected to conclusions.”

In contrast to Nestle, the dean of evidence-based debunkers, John Ioannidis, who is a professor of medicine at Stanford University’s Prevention Research Center, concurs with Allison. “This is an excellent article that highlights some of the many myths of obesity research,” he said via email. “Faulty health claims are often made with little or no evidence, or with data that are clearly biased. Then these claims are propagated by a conglomerate of expert opinion, distorted media coverage, and inertia.”

One of the particular problems with obesity research, he continues, is that when you compare the field, say, with drug research, there are far fewer randomized trials on prevention and public health. “We should aim at attaining more rigorous evidence and more realistic estimates about how much preventive interventions work,” he said. “This would require sponsoring a sufficient number of large-scale preventive, public health-oriented trials. With few, small trials the evidence remains potentially fragmented and prone to exaggerated and inflated results. Observational studies are useful, but over-reliance on them can cause a credibility crisis in public health research.”

HOW DO WE KNOW TO EAT THIS, NOT THAT?

Of course, weak measurement isn’t just a problem for academic credibility, it has a direct bearing on our health. “Think about the first time you got on an airplane,” said Peter Attia, “how much rigorous science had worked out the nuances of aerodynamics? Or when you first took an antibiotic for a certain type of infection, what level of evidence was necessary to let you and your physician feel comfortable about that being a reasonable risk/reward scenario? And yet, when your physician or your nutritionist tells you to eat ‘that’ but not ‘this,’ how much evidence is supporting the recommendation?”

Attia, a former physician and consultant for McKinsey & Company, recently co-founded the nonprofit Nutrition Science Initiative with science writer Gary Taubes. Their shared concern that dietary claims were lacking the kind of scientific rigor expected in other areas led them to seek philanthropic funding to support teams of top researchers to try and produce better data. But their project also reflects a frustration with how science is currently funded. “We spent nearly $5 billion to build CERN, and several billion dollars a year running CERN,” said Attia, “but we can’t spend 50 million dollars a year doing best-in-class science on the single most important question that impacts human health right now?”

But if you keep foisting badly measured policy experimentalism on the public enough times in the name of solving the obesity crisis, all the while claiming that science shows that this will work, then the public will simply stop trusting science and go on eating based on a much more internally reliable measure: pleasure.

But even 50 million dollars pales against the amount of money a pharmaceutical company will put into one drug, much of it directed at massive experiments to find effects. This is one of the issues that troubles Heymsfield, who as executive director of the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, heads the largest academic-based nutritional center in the world. Even the best evidence in obesity research — the randomized control trials — mostly have tiny samples and short time frames. Given how difficult it is to show positive effects in drug trials that cost hundreds of millions of dollars and involve following thousands of people over several years — and how skeptical we often are about the validity of those results — we show, he said, little comparable skepticism about the very small effects found in nutrition studies involving hundreds of people over several months.

But while skepticism may be a cardinal virtue in our information society, it represents a particular problem for a public health community searching for solutions to obesity. If a problem has been poorly measured then it stands to reason that any given solution to that problem may not be a solution at all. But if you keep foisting badly measured policy experimentalism on the public enough times in the name of solving the obesity crisis, all the while claiming that science shows that this will work, then the public will simply stop trusting science and go on eating based on a much more internally reliable measure: pleasure.

DOES ONE POUND EQUAL 3,500 CALORIES?

As with any field, public health has a radical wing who want to push past limited evidence and say that science has provided enough of a rationale to take action against the enemies of health (in obesity, as we’ve discussed before, the current enemy is sugar). To the hardcore evidence-based wing, all this is just bad — or at best, uncertain — science with an unhealthy dose of media-proselytizing to give it the certainty required to become policy. The enmity between the two groups is often palpable at scientific meetings, bordering on a clash of incommensurable values: the need for action now versus the need to do the best possible science; “we’ve got to do something!” versus “but what if that something is wrong?”

But there is a revolution in measurement coming to public health. Heymsfield sees scientists with more quantitative backgrounds and skills entering the obesity research field and trying to come up with ways of measuring what has not been measured well or at all. One of these is Kevin Hall. Trained as a biophysicist, he now runs a biological modeling lab at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. As he sees it, “the field of nutrition and metabolism is actually quite quantitative, when you compare it to other fields, like immunology — at least at the physiological level.” The problems, he explains, are getting accurate data and then integrating that data in a mechanistic way.

Hall was responsible for filling in the crucial measurements that elucidated one of the most widespread myths highlighted by Allison et al.: the idea that small, consistent changes in energy intake or expenditure will, over time, lead to large changes in weight. The assumption appears to have been based on the 1958 calculation by Max Wishnofsky that one pound of body fat gained or lost is equal to 3,500 kilocalories. This seemed to give people a convenient way to estimate weight loss through diet or exercise, while promising extremely convenient results. If you simply knocked off a 100 kilocalories from your energy intake each day — a ten-minute jog, or a mile walk — you’d end up losing over 50 pounds in five years. Little wonder that early proposals for soda and fat taxes promised to save Americans from themselves: pay a little more, consume a little less, watch a lot of weight disappear in a few years.

Hall first heard the claim listening to a dietician make a calculation for an obese patient. His intuition told him that this calculation was incorrect and would lead to exaggerated weight loss predictions. When he asked for a reference, he was pointed to a nutrition and dietetics textbook. “I subsequently found the mistake everywhere I looked.” People weren’t stopping to think “about the dynamic interaction between energy intake and expenditure, which is complicated,” he says. What they failed to take into account was that “the rate of weight loss changes over time and is primarily determined by the imbalance between energy intake and expenditure — a value that also changes over time.” To radically simplify his model, this means that cutting calories in your diet leads to a decreasing calorie expenditure, which in turn slows weight loss until weight eventually plateaus after a few years. “Of course,” says Hall, “cheating on your diet will cause your weight to plateau much sooner.” In the case of soda taxes, Hall and researchers at the US Department of Agriculture showed how static modeling overstated weight loss by 346 percent after five years.

“We know the kind of mathematics to apply,” says Hall, lightheartedly chiding dieticians for not getting to grips with calculus. But the more serious problem is finding the best data to set the parameters for an accurate and precise model. And when you move up from controlled feeding experiments that define these physiological parameters to the population at large, things rapidly go downhill. “We still don’t have good ways of measuring what people eat when they are outside a metabolic ward,” said Hall. “And until we solve that problem were going to be at an impasse. If we can’t measure what people eat, then how are we going to understand what the relationship between diet and health actually is?”

What we need are quantitative theories, he says, and then to take a group of people, manipulate their food environment in a controlled manner, where we can accurately measure food intake behavior for a period of months or years, collect the data and then see if the theories match up with the experiments. Right now, it seems that we’d rather implement poorly controlled experiments on the population as a whole instead of funding actual experiments to see what happens to people’s behavior and energy balance.

“Until we solve this problem,” he says, “all bets are off in making strong claims about the public health consequences of diet intervention.”

Previously: The Sugar Wars: Science’s Fierce, Geeky Debate Over Soda

Trevor Butterworth is a regular contributor on science and technology for Newsweek. Photo courtesy of James Vaughan.

How Race Is Lived In America

“Blacks and whites, on many measures, see the world in quite different ways. And this has direct implications on how we advertise.”

The Internet Talks To The Internet About The Internet, Makes Fun Of You

One of our greatest fears as social animals is that someone (or a large group of someones) might be mocking us behind our backs, in ways so silent or subtle that we might never know that we are in fact being mocked. Is this happening to you, right now, on Twitter, while you remain ignorant of it? Yes. Yes it is. Here’s how it’s happening.

And when you’re done there: “I would like to discuss (hot on the heels of the excellent subtweet Branch) what the nature of the Twitter canoe is. Let’s canoe this up. What is it? What are its defining features?”

Dear Mom

(This letter is an excerpt from the new memoir Public Apology, out today!)

Sorry for choosing Hannah and Her Sisters when you asked me to go out and rent some movies for our family to watch to get our minds off the fact that Dad had been diagnosed with cancer.

You remember, I’m sure, that this was just a couple weeks before I graduated from high school. It must have been a weekend, because we were all at home in the afternoon. Dad walked in to the TV room with his friend David Landy. You could tell that David Landy had been crying.

“The doctor just hit me with it,” Dad said. “Boom.” His eyes looked like they weren’t really looking at us, and his voice sounded like it was coming from far away. But he said he thought that the doctor had done the right thing. “So I’m just gonna hit you with it.”

The cancer had started in his lung. At least that’s what they thought. It was hard to tell. By the time anybody knew anything, it had spread to his brain and his lymph nodes and his spinal column and everywhere. ‘Metastasized’ was the unfamiliar word. The doctor had told him that he would be dead in two months.

We sat in the TV room for a long time with the TV off.

Deb cried. I went upstairs and looked at myself in my bathroom mirror. I looked normal, but I felt like a different person. Like the person who I was when I’d woken up that morning was no more, and that this new person that I had become was hidden inside my head, looking out through fake eye sockets at this thing in the mirror that was only a shell. Why wasn’t I crying? Why didn’t I even feel like crying? Shouldn’t a person be crying after learning that one’s father is dying? It felt like a dream, like I’d wake up the next day and this wouldn’t be happening.

But I knew it was real, and that it was a big deal. One that I felt wholly unprepared for, despite the fact that Dad had come into the kitchen a few weeks prior and asked me to get off the phone so we could talk, and endured the put-upon expression I fixed him with before telling me that he was having some medical tests. He’d said that he’d been coughing up blood and that he didn’t know why, and that it might be serious. It might be bad, he’d said. He hadn’t said the word ‘cancer,’ though, and I had quickly pushed it out of mind and not given it much more thought. Because I was so good at being what sitcoms and movies had taught me teenagers were supposed to be like, and convincing myself that you and Dad didn’t mean anything to me.

“Dad has cancer.” I said it out loud to myself. “Dad is dying.”

I stood there for a moment, blinking, wondering if this would jog me into a burst of emotion that felt more real.

“This is what it feels like when your dad is dying,” I said.

I wrote Dad a clumsy note to tell him that I loved him. “You’re like Superman to me,” I wrote. I didn’t know what else to write. I went into your room and tucked the note under the pillow on his side of the bed. The house was quiet.

Later, back down in the TV room, Dad told us he was going to fight the cancer as hard as he could. Despite what the doctor had told him, he was determined to do whatever it took to beat it. “I’ve been a fighter all my life,” he said. “I’m not going to quit now.”

He came over to where I was sitting on the arm of the couch and looked me hard in the eye. “I’m gonna need you here with me on this one,” he said. “Don’t run away from me. I need you here with me and as part of this family. And I need you to be present. Don’t go and hide in the bottom of a bottle or inside the tube of a bong.” I told him I wouldn’t.

Dad’s parents drove down from West Orange. Thea was crying as she walked in the door, tissue paper already crumpled into balls in her hands, her face twisted into an expression that made it hard to imagine that she would ever be able to smile again. Pa looked stooped and older than he’d ever looked before.

At dinnertime, no one felt much like eating. I forget if it was you or David Landy who had the idea that we should rent some movies to watch, but I thought it was a good one. Get our minds off the news, lighten the mood, to the extent that that might be possible. I remember Dad agreed, and that he said to get comedies. “I want to laugh,” he said.

I volunteered to go to the video store. I wanted to get out of the house, out of that atmosphere, even if only for twenty minutes. I liked feeling that I was helping, too, even in a minor way. Alone in the carport, once the door closed behind me, I took what felt like my first full breath in hours.

Soft-rugged and fluorescent-lit, the video store gave me the same dissociative feeling as looking in the mirror had. There I was, in this very familiar place, a place where I’d spent so many hours of my life doing exactly what I was doing then, scanning the collection, searching for titles that I knew or new ones that looked intriguing, a place where there were always faces I recognized — Ms. Maxwell, an English teacher at my school, worked there some nights — a place where people met and stopped to chat. There I was, just like always, except not at all like always. Walking around the store, I couldn’t help thinking about what I looked like to the other people around me. I saw Mr. Johnson, Jeremy’s dad, there that night. Did he recognize me? Did I seem the same? I suppose I did. I wasn’t trembling or sobbing or breathing into a brown paper bag, there wasn’t blood dripping from my nose or soaking through my shirt from my chest. I was just standing there, my jaw set firm, squinting slightly as I scanned the titles on the plastic-sheathed spines of the VHS boxes on one of the racks in the comedy section. I felt like a spy. I felt like a liar.

I don’t know how exactly it happened. I guess I was caught up in thinking about this stuff, in a sort of daze, as I was choosing videos. I got A Fish Called Wanda, and, I think, Porky’s, which was always a favorite of Dad’s and mine. And then I found Hannah And Her Sisters. It’s weird, because I had seen that movie before. We all had, and liked it. We were big Woody Allen fans. But in remembering that we liked it, and in the daze I was in without really knowing I was in it, I forgot that one of the main plotlines of that movie revolves around Woody Allen’s character believing he has a brain tumor.

I stopped on the way home to pick up my girlfriend. I had told her the news and asked that she come over.

When we got back to our house and got out of the car, she saw the bag from the video store and asked me what I had rented. When I told her Hannah and Her Sisters, she stopped suddenly. “We can’t go in there with that movie,” she said. She reminded me what happens to Woody Allen’s character.

“Oh my god,” I gasped. We were standing in the carport. “How could I have forgotten that?”

I cursed myself and shook my head. I felt like someone who has been hypnotized onstage, awakening to the sound of the magician’s finger-snap, looking around to see who’s watching. It was frightening — one of those moments when your trust in your own brain falters.

Thank god she had stopped me. Thank god I hadn’t gotten inside and popped it into the VCR. “Hey, is everybody ready to laugh?! This movie is about someone who thinks he has cancer!”

I didn’t know what to do. She said we should go back and pick a different movie. I opened the door quietly and called you over from the TV room where everyone was waiting. “Here,” I said, handing you the two other movies. “You can start watching one. I have to go back to the store.”

You looked at me quizzically. “Why? What happened?”

I showed you the box for Hannah and Her Sisters. “Woody Allen’s character is a hypochondriac who thinks he has cancer.”

“Oh.” Your voice fell. “Oh.”

“I… I don’t know what I was thinking,” I stuttered. “I forgot.”

“Yes…” You tried to be comforting. “I would like to think that Dad could find that funny right now, but I don’t think he could.”

I closed the door behind me. I don’t know what you told everyone about where I was going. I think you started A Fish Called Wanda.

Previously: Dear Coot Veal

Dave Bry’s Public Apology, a memoir based on the Awl column (but made mostly from new, never-before-published material) is published by Grand Central Publishing. (Order a copy here!)

Dave Bry has a lot to apologize for.