New York City, May 9, 2017

★★★★ Children were kitted out in puffy coats to go to school, but here and there an adult wore only a suit. Wool was unwearable and unnecessary, the chill having retreated the tiniest bit more. A cloth cover, inflated by the breeze, swelled and pulsed over a scooter or motorcycle, the shape within completely impossible to know. The clouds that had dulled the late day then caught and spread the shine of the rising moon.

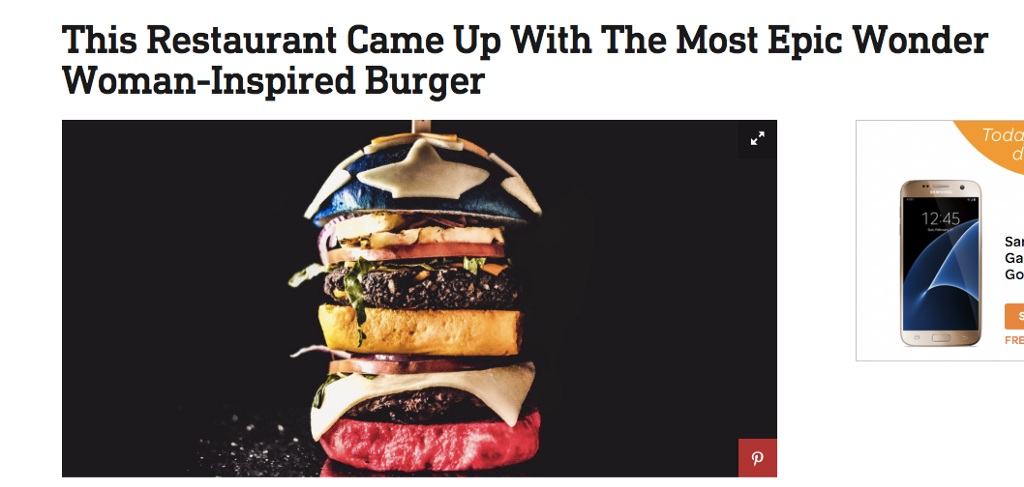

Does The Wonder Woman Burger Even Count As Food?

Let me give you a hint: no.

The burger is more a throwback to the Lynda Carter era than a reconstruction of Gal Gadot’s new costume. The top bun is dyed shiny blue like the bottoms to Carter’s very ’70s super suit, and festooned with stars made from white cheese. Meanwhile, the middle bun is gold, and the bottom one is red — and in the middle are two patties, lettuce, tomato, red onions, and the world’s second-most-hated ingredient, pineapple.

Not long ago, we entered the territory of food that you don’t really eat, at least not for taste or nutrition purposes, you just perform that you purchased it as a way of becoming a native human ad for two things at once: a gimmicky Florida restaurant group and a reboot of a reboot of a reboot for an upcoming movie. It can’t possibly taste good. But has anyone asked the burger if it’s a feminist?

Bring a Superheroic Appetite for This Three-Tiered Wonder Woman Burger

I wish we didn’t have to talk about this.

Check Your "I Don't Know" Privilege

The perfect thing for the Trump age is bragging about your ignorance.

It used to be that the assholes on Twitter were the ones who showed you how much more they knew than you by just quoting a sentence or paragraph but not identifying the source. Exclusion by proxy: everyone who’s in the know already knows. Well, times have changed, and social media has inundated us with feeds to keep up with, and just like college students cramming before a final, the thing now is to perform a sort of Zen with that overwhelmed-ness, an existential reconciliation with the unknowability of the universe, or even a desire to go back into the cave of ignorance. The old not knowing was extra knowing. The new knowing is not knowing, and letting everyone know about it.

It’s sort of like the Last Man game, where players try to go as long as possible without finding out the results of the Super Bowl, but for What People Are Talking About Today On The Internet. It’s a point of pride, a half-nihilist, lol-nothing-matters way of looking at the internet, wherein everything is just one outrage cycle after another and it will all blow over eventually and if something’s really important, you figure, it will make its way to you through all the noise.

It sort of feels good to abstain from participating in the cascade for a day, having missed an entire meme cycle, doesn’t it? Like going on vacation and coming back and just deciding to declare meme bankruptcy? You missed a week, but there will always be more memes. So why then, do you feel the need to gloat about what you missed? Are you bragging about the vacation, or what you know you took the vacation from?

The reaction once you realize you can’t continue to willfully ignore a certain subject is always something like, “ugh am I finally going to have to learn what that is.” Like for example, I didn’t find out who Tom Holland was until 3:09pm EDT on Monday. That morning, I saw tons of what I would call “entertainment” people tweeting about him, and by the afternoon the name had hung around so long that I eventually clicked on a video of him performing Rihanna’s “Umbrella” on “Lip Sync Battle” when it showed up in my Twitter feed. Every meme or news item has its watershed moment, beyond which most reasonable people can’t ignore it—this is what Facebook algorithms were designed for. That said, I still don’t know the story behind Pepe the Frog and you can’t make me.

Watching people tweet or debate on Facebook about something you haven’t the foggiest idea about is kind of wild. It’s when you move past that feeling of FOMO that you feel a sort of ecstatic release. What is the purpose of knowing anything for a short period of time, only to have it replaced by some other fact or news item ten minutes later? If for some reason, you miss the big press release about the Starbucks unicorn frappuccino, you can sort of put it together from context clues. New drink: blue, pink.

Outwardly it does seem like a kind of silly thing, like the Dove bottle fiasco (haha remember), that you could just choose to not pay attention to, with a little backhanded flick-wave that Daniel Kaluuya makes to shoo away an ad in one of my favorite episodes of “Black Mirror”:

But it’s a form of privilege, not having to know things. And one of the most insidious parts of it is the vast privilege that is even entailed in knowing what you’re not going to know. You only know after you stumble across the thing, choose not to engage with it, and then you know.

That said, there is a relief in learning about something later, comprehensively and on your own terms, and feeling thankful that you didn’t know it in a time and space when everyone was being super annoying about it on Twitter. A colleague of mine learned about the Kendall Jenner Pepsi thing a week later, but by that time it had blown over. Not really a big deal. How nice for him.

Sometimes we cultivate these gaps in our knowledge, almost as an affectation, which feels a little unfair. The New Yorker critic Emily Nussbaum has famously said she’s never seen The Godfather. These lacunae used to be sources of trendy humiliation and shame, but now we’ve come to a point that our “book guilt” and “late passes” are so normalized that we celebrate them, and hold them up like badges.

The Literary Critic’s Shelf of Shame

We used to consume culture and then immediately perform that consumption as a proxy for a relevance and coolness. It was also conveniently a way of employing our liberal arts degree to think critically about the world around us. Now, in the age of Trump, flouting your ignorance is a way of displaying your power. Look how much I can get away with without having done the reading!

But it’s also reasonable—not everyone can see every movie, TV show, play, whatever. Everything is kind of a choice, right? So then why are we bragging about our choices to abstain? Can’t you just choose and shut up? The answer of course is no, none of us can ever stop finding a way to one-up each other, so long as we have a space to do so.

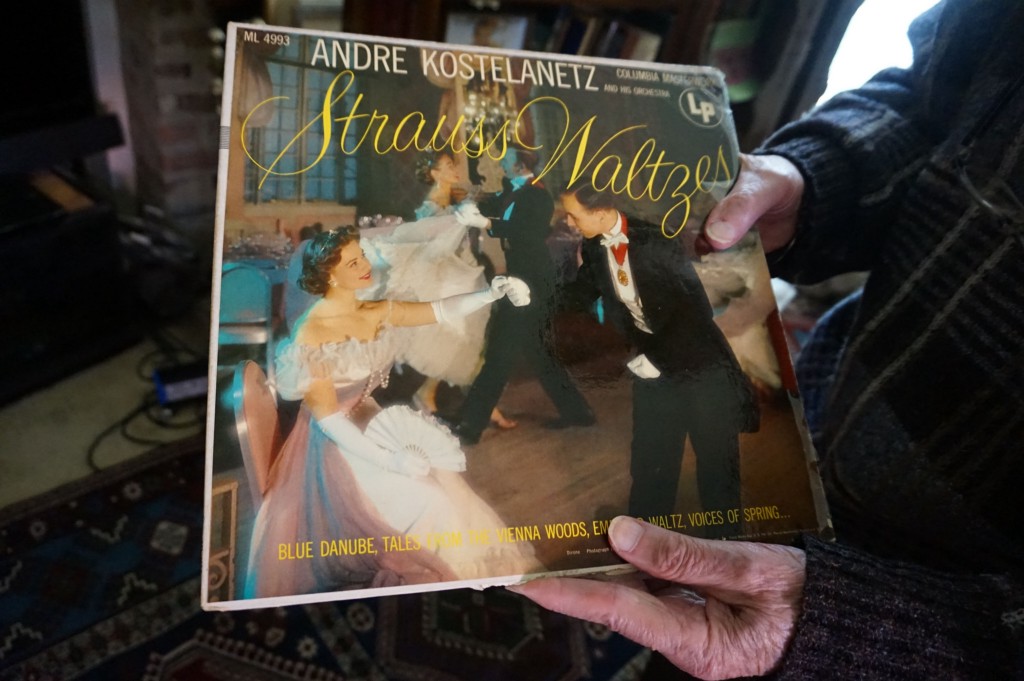

What Do I Have To Do To Earn The Nickname "Waltz King"?

I went to go see The Lost City Of Z the other weekend (which, if you haven’t seen it, GO, please, it’s astoundingly good), and there’s a scene early on in the film where the main characters attend a party and there’s a Strauss waltz playing. I nearly had a fucking aneurysm in that moment, not only because I could not figure out which Strauss waltz it was — if you know, please tell me, also: all waltzes sound the same — but also because I realized I had yet to write about Strauss for this column. What a gargantuan disappointment I am to myself and others!

By Strauss, in this case, I’m of course referring to Johann Strauss II, often confused with Johann Strauss I, his father. It’s not that I have no interesting in Strauss I — I do, in a passive but respectful way — but it’s Strauss II who is really responsible for all of the essential bangers of the late 19th century. I say this, and I know it sounds insane, but after the past couple of weeks of late Romantic era weirdness, wouldn’t it be great to listen to some pop music? It did exist during this time! It wasn’t all moody Brahms. Because that’s what Strauss II was, the so-called “Waltz King,” the savior of dance halls and fancy parties and Friday nights. It is diminutive (maybe) to write something like “Strauss II was the Katy Perry” of the 19th century but oops, there it is, please do not send me to music criticism Hell, thanks and goodbye.

There is such a fantastic discography of Strauss pieces — all special and fun in their own way — that it is genuinely impossible for me to pick one to share with you, so I’m going to share three: an overture, a waltz, and a polka.

The overture is from his operetta Die Fledermaus which translates to The Bat in German (“the flying mouse,” obviously). The plot of Die Fledermaus is: it doesn’t matter. Honestly it doesn’t. The overture was one of the first classical music pieces I can remember hearing in my whole life (it is a favorite of pops orchestras and community orchestras and the like), and the less you know about it, the more you can enjoy it, in my opinion. Whereas other overtures I’ve written about are not overtures in the Broadway sense, that’s almost literally what the Die Fledermaus overture is: a preview of the music to come later on in the operetta. It’s instantly fast-paced and broad and enjoyable; it sparkles with personality. Despite this not being a waltz (at least, not on paper; in pure form, it’s kind of a rondo), it has those signature waltz themes. It sounds like you can dance to it, is what I’m trying to say.

Do you have a favorite melody within it? Is it the one at 1:46 — airy, light, and playful? What about the one at 2:50? Heavy and saccharine, like a flourless (German? Strauss was Austrian so nvm) chocolate cake? Here’s mine: it’s at 5:13. It builds so perfectly and quickly. It’s a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it type of section, brassy and strong, but by no means heavy, and it’s finished less than a minute after it started. This is a good introduction to Strauss because it’s an impossible-to-dislike piece of music. Honestly. If you don’t like this, do you also dislike dogs? Or ice cream? Or the hit television show Chef’s Table, the only good show on any channel or streaming service combined?

Anyway, let’s get into waltzes. It is impossible to pick a perfect Strauss waltz, so I won’t pretend that this is the best one. It’s just one I’m partial to, and it’s Rosen aus dem Süden aka Roses from the South. Here’s what I like about Rosen aus dem Süden: it tricks you. It starts so slowly and sweetly. It’s a grand romantic gesture for a full freaking minute. You wouldn’t even know it’s a dance at its inception. Waltz, yes, dance, no. It’s almost a little bit meek or unassuming, and then around the 1:03 mark, it absolutely pulls the rug out from under you. The crash cymbals are more or less calling you an idiot for thinking otherwise. Roses aus dem Süden is such a wonderfully textured waltz; it’s lush as fuck. Dense and perfect in every way. Can’t you imagine literally any movie setting a scene to this and having it be perfect? Can’t you imagine cleaning your apartment to this? Can’t you imagine lying down on the floor after reading a day’s worth of Twitter dot com to this? According to a basic search, it has been used in both an episode of Star Trek and in Sophie’s Choice, of which I’ve seen neither because I’m not a goddamn nerd.

And then: a polka. You’re welcome for this one, truly; I expect thank you emails from everyone. Here is Strauss’ Tritsch-Tratsch Polka to which you might be saying, “what???” but it more or less translates to Chit-Chat Polka and is somewhat unofficially dedicated to the Viennese habit of gossiping????? But in a nice way?????????? Because it was an essential part of their culture?????????????????

Wow, okay, let me recover for a moment.

The Tritsch-Tratsch Polka, besides being a nightmare to type over and over again, is a joy unto itself. This is a dance. It’s short and abrupt and aggressive in nature. It demands attention and not politely. And you’ll have it stuck in your head the rest of the day, which again: you’re welcome. Want to listen to a fun thing in it? Okay, trust me here. There’s a melody that starts around the 0:50 mark. You’re listening? Good. There are some timpani notes throughout that melody and they sound… weird…? Right? That’s because the timpanist is doing a glissando on the drum. This occurs when the timpanist hits the drum, and then she (all timpanists are women, btw) leans forward on the tuning pedal to shift the note up the scale as it reverberates. I’ve written about glissandos before, on the xylophone, previously, in Pétrouchka. But on a timpani they’re so much more comedic. This is a noise for a clown. I love it.

It is good this column comes out on Thursdays (ed. note: Wednesday today, but just pretend), because I’ve more or less given you three different examples of what “going out” music would sound like approximately 150 years ago. Go have fun out on the town and be thankful for Johann Strauss II for inventing what it means to party.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

What It's Like Out There

Everyone’s talking about it.

A vast reservoir of clichés has developed over generations of these supposedly lame conversations, a byproduct of the ingenuity the topic demands. And now even these clichés can be amusing for the fact that they’re so tired. I’m being serious when I say that in the hands of a master conversationalist, a well-timed, perfectly placed “Hot enough for you?” can serve delight on a very hot day or (even better) a very cold one. (“It’s not the heat, it’s the humidity” is starting to gain similar status.) It reminds us, by dint of its banality, of our common, corny American heritage. This is hardly boring; it’s democratic, a shared language that allows us to connect with strangers easily, noncommittally and without causing offense.

Awl pal Dave Bry’s Letter of Recommendation for talking about the weather is the pure apotheosis of that column. There is nothing to add.

Perfume Genius, "Die 4 U"

Let’s just be quiet this morning.

No one wants to talk about the melodic similarities between Perfume Genius’ “Slip Away” and Collective Soul’s “Shine,” huh? I get it. Fine by me. In fact, I am okay if no one wants to talk about anything. Everyone can shut up for a long, long time, particularly those people who don’t know what the fuck they are talking about, which is almost all of them. You know what? Let’s just listen to the new Perfume Genius track and keep our mouths closed. It is a situation that will make sure we all have a morning we can enjoy.

New York City, May 8, 2017

★★★★ The contradiction between the high warm sun and the cold air was confusing for a few hours, till the edge was finally off the chill. The still-new green of the trees was blazing and tossing. There were clouds enough to make the light in the middle distance different from the light close by; pedestrians were sharply drawn while the Empire State Building was dull and indistinct. Even the gray interludes had a luster to them. The white-brick tower shone clean and pure and then faded, the grime on its bricks darkening into view in the weaker illuminati0n of the cloud shade.

Good News For People Who Love Salty Foods

Nobody has any idea what the salt is doing in your body.

Salt. You know it’s bad because it tastes so good. You’re not supposed to have too much of it in one day or you’ll get hypertension and heart attacks and that burning feeling on your tongue. It also makes you retain water. Or does it? Turns out the scientists are not sure.

Some new studies on Russian cosmonauts in isolation tested what happened when they had high, medium, and low levels of salt in their diets. They measured the salt in their blood and urine and also the volume of their urine. Weirdly, the cosmonauts were LESS thirsty on the high-salt diets, and MORE hungry??? This feels intuitively right to me, and indeed some scientists later in the article posit that the “thirst” being cultivated by bar nuts and salty snacks is actually just a kind of a physical urge to drink, or consume. Anyway the best part of the article is various other scientists reading the findings and reacting to them:

Dr. James R. Johnston, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh, marked each unexpected finding in the margins of the two papers. The studies were covered with scribbles by the time he was done.

“Really cool,” he said, although he added that the findings need to be replicated.

Science is indeed really cool, but there is something sort of alarming about how calmly in stride the salt scientists are taking this one:

Why Everything We Know About Salt May Be Wrong

“The work suggests that we really do not understand the effect of sodium chloride on the body,” said Dr. Hoenig.

We know nothing! Eat some potato chips.

Why The Trump Transcripts Are So Maddening To Read

And why we should still keep reading every word.

A transcript is a record of fact. Which is why the verbatim transcript of interviews with President Trump are fast becoming the political news fetish object of the current moment. Sure, a transcript can be cleaned up, and different media companies treat the Trump’s speaking with varying standards (of the two most recent interviews, CBS cleans out the uhs and ums, the Associated Press doesn’t, for instance). But with Trump, you can’t extract from either sort of transcript any personal truths that are blind to the objective truths that the transcript presents. You couldn’t say, no, this is actually a president, this is exactly how a leader ought to talk and reason, because even with the uhs and ums cleaned out and the spoken sentences made to look like written ones, Trump’s discourse isn’t coherent. The sentences are grammatical (mainly because he keeps them so simple), there’s little disfluency. This isn’t the word salad of, say, a Sarah Palin. This is coherence salad. One example:

PRESIDENT DONALD TRUMP: Well, I never spoke to him about it. Honestly, he’s never asked me about it. I said, number one, I’m under audit. Right now, I’m under audit. After the audit is complete. It’s a routine audit, but I have a very big tax return. You’ve seen the pictures. My tax return is probably higher than that from the floor. When you look at other people’s tax return, even other wealthy people, their tax return is this big. My tax return is this high.

The expert reader of transcripts is torn when it comes to these. On one hand, you know that a verbatim transcript offers language that’s not quite speaking and not quite writing, which is why it can be unsettling. We don’t speak the way we write, and the transcript, though it’s a text, doesn’t look much like writing. Dwight Eisenhower was frequently mocked for his “garbled syntax,” and his speechwriter, Arthur Larson, defended him with a legitimate point in his memoir: “Before anybody makes fun of the alleged garbled syntax of Eisenhower’s answers as literally reported syllable by syllable in the papers,” he wrote, “let him just once read an equally literal stenographic transcript of something he himself has said, in a congressional hearing, or in an extemporaneous speech, or on a witness stand.”

And yet what you find in a Trump transcript is even weirder. A lot of the commentary about any particular Trump interview covers the facticity of his claims, his retreading of campaign material, the dodges. While such parsing is necessary, it ignores something more basic: the amount of work that a reader has to do to interpret the talking to make it coherent. Linguists talk about coherence as a connectivity of themes, as the progression of ideas, or as a perceivable consistency among all the things a speaker wants to achieve. We’re used to making sense out of superficially disconnected sentences — we do it every day, with each other — but Trump requires much more work because he commits to everything and yet nothing. There’s little sign of a struggle to stay on topic or to stay within the conversational frame. Take, for instance, this:

TRUMP:…First of all I think he’s a great man. I think he will be a great, great justice of the Supreme Court…I’ve always heard that that’s [meaning appointing a justice] the biggest thing. Now, I would say that defense is the biggest thing. You know, to be honest, there are a number of things.

Or this:

TRUMP: I have great relationships with Congress. I think we’re doing very well and I think we have a great foundation for future things. We’re going to be applying, I shouldn’t tell you this, but we’re going to be announcing, probably on Wednesday, tax reform. And it’s — we’ve worked on it long and hard. And you’ve got to understand, I’ve only been here now 93 days, 92 days. President Obama took 17 months to do Obamacare. I’ve been here 92 days but I’ve only been working on the health care, you know I had to get like a little bit of grounding right? Health care started after 30 day(s), so I’ve been working on health care for 60 days. …You know, we’re very close. And it’s a great plan, you know, we have to get it approved.

This is the talking of someone with power, the sort of power that doesn’t come from consensus-building and organizing. We don’t really need a transcript to tell us this, but it’s there. Trump talks to occupy space and run down the clock. He’s prompted to speak by a question but rarely answers the question; he only has to talk long enough to execute his turn in the conversation before the questioner wrests it away. That’s the extent of the coherence. Otherwise, he cajoles, he lies, he brags, he cuts down, and the effect on the transcript reader is nowhere near what Trump can have intended.

At the same time, reading a transcript by a sitting president plunges you deep into your own expectations for what a president ought to sound like. That is what Arthur Larson didn’t touch on in his defense of Eisenhower: politicians desire the accuracy of the recorded (and therefore the precisely reproduced) quote, but not the ramifications of the accuracy. In truth, the U.S. presidency has a long, troubled relationship with the verbatim. The first president who explicitly asked not to be quoted verbatim was the famously taciturn Calvin Coolidge. (He was also the first one to speak on the radio, in 1923.) He met regularly with journalists and didn’t allow them to quote him directly or even write down exactly what he said. For my book Um…, I found an exchange in which Coolidge chewed out a reporter he saw taking shorthand notes:

“Are you taking down in shorthand what I say?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Now I don’t think that is right. I don’t think that is the proper thing to do,” Coolidge said. “I don’t object to you taking notes to what I say, but I don’t quite throw my communications to the conference into anything like finished style or anything that perhaps would naturally be associated with a presidential utterance.”

Like Coolidge, Harry Truman also forbad journalists to quote him verbatim. Recording equipment was first put into the Oval Office by FDR because he was tired of being misquoted, but he (and subsequent presidents) retained control over the recordings and transcripts.

The culture of journalism has evolved its own tastes toward the vérité. In the late 1980s, political columnist Maureen Dowd came to prominence partly based on her cheeky willingness to quote George H. W. Bush verbatim. Many of those same quotes sent writers searching for diagnoses of aphasia or other pathology for Bush and later for his son.

It’s also true that our ideals of “sounding presidential” are rooted in our own times. If we had recordings of past presidents, we likely wouldn’t find them very presidential either to the ear or on the page. Thomas Jefferson, for example, who embodies many of the traits that we expect from an American president (except for the slave-owning, of course), was apparently such a fumbly talker that he didn’t give any speeches, and when he did, they were brief. But again: even Trump transcripts are not normal.

It’s also quite possible that Trump’s speech is just the speaking of an old man.

As adults without any neurological disease get older, the grammatical complexity of their sentences declines (people in their twenties use an average of 3 clauses per sentence; people in their seventies average about 1.4). The density of propositional content in their sentences declines, as do word-finding abilities (which explains, by the way, Trump’s restricted repertoire of, say, adjectives: “horrible,” “terrific,” “great,” “big,” “nice”). In studies of the coherence of a discourse, the older talkers are less able to stay on topic, even though sentence to sentence remain connected to each other. However, older speakers produce more coherent discourse when they’re talking with younger people — as Trump often is. The younger speaker — or the interviewer — “appears to scaffold the performance of their elderly partner by introducing ideas and phrases that can then be developed by the elderly individual,” wrote Lauren Saling and others in a 2014 research article in The Journal of Gerontology.

This is what we do next: we weaponize the verbatim transcript. Stop cleaning the transcripts; stop displaying soundbites and printing cleaned quotes. Print the whole thing, each and every time. Annotate them, don’t cherry pick. Any given speech or interview is not a continuous series of soundbites, the juiciest of which gets passed along. Rather, a soundbite is extracted like a jewel from the mud. A transcript offers a chance to make sense of the mud of regular talking, so let’s get the mud of Trump’s regular talking to work against him, amplified by the inherent weirdness of the transcript. The verbatim transcript is the chink in the autocrat’s armor — as long as you have a free press in which to print them.

Michael Erard is the author of Um…: Slips, Stumbles, and Verbal Blunders, and What They Mean and Babel No More: The Search for the World’s Most Extraordinary Language Learners.