History Is Written By The Russians

How a nation forged an identity from the Soviet defeat of Nazi Germany.

It’s easy to get sick of the word “victory” in Russia — everything is victory this and victory that. A few years ago, on May 9 — what Russians call “Victory Day” — I pushed into a metro car headed to Moscow’s Victory Park. When the doors opened, I was swept to the bank of escalators by hordes of revelers bedecked in costume Red Army uniforms or garish tee shirts that proclaimed “VICTORY!” and “Thank you, grandpa, for our victory,” which rhymes in Russian. To the left, I saw the Victory Arch, and I shoved my way toward it, past groping teenagers and thronging babushkas with their wide-eyed, seraphic grandkids. When I finally broke free, it was into a circle that had opened around five red-cheeked, older men, their shirts unbuttoned in the spring sun, howling the most popular of Victory Day songs, immortalized by crooner Lev Leshchenko and titled, of course, “Victory Day.” This Victory Day, the chorus runs in my painfully literal translation,

The scent of gunpowder still on the air,

Is a celebration

Of those whose hair is already graying,

It’s joy

With tears in our eyes.

Victory Day!

Victory Day!

Victory Day!

A waifish young woman with a crown of flowers kissed me three times on the cheek in the traditional Russian fashion: left, right, left. One of the men dug up a bottle of vodka from his bag, another produced tiny paper cups, and I found myself, hours later, singing the song again, only this time I was perched on the railing of a downtown Moscow bridge, the Kremlin looming over me and the thousands of people who had come out to celebrate. I think the person next to me had an accordion, and I think my friend Zhenya was holding my hand as we shouted again, “Victory Day! Victory Day! Victory Day!” under the fireworks that bloomed over St. Basil’s Cathedral and Victory Park.

As the sun rose and I felt I might burst with drunken goodwill towards Russia and Russians. I had lived in Russia for three years, from 2005–2006 and again from 2009–2011, which is not so long, but it was long enough to observe the contortions of a nation hell-bent on reclaiming what it sees as its greatness. And that greatness can be boiled down to one word that might even make Donald Trump perk up: “Victory.” But where Trump’s “winning” is intentionally undefined, in Russia there is only one victory that really matters.

This year, Russia will celebrate the 72nd anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany. It is hard to overemphasize how important that victory is to Russians. Of all their holidays — and they have a lot — Victory Day is the biggest; it makes our Independence Day festivities look muted, and it is suffused with something more than simple patriotism. As much as Victory Day is about celebration, it is a commemoration of the unspeakable suffering and the sacrifice of a generation of men to save the world from evil. But it is also a reaffirmation of Russia’s national myth. Russian identity in the Putin era, complex as it is, cannot be extricated from victory in World War II. As Vladimir Solovyov, a talk-show host and pundit, wrote in the introduction to his 2009 book, We are Russians! God is With Us!, “[our soldiers] sacrificed for everyone, and they left us with an altogether unique identity, an identity that cannot be shared by the Germans or the Italians or the French — no, not a single other nation on Earth can share it — the identity of victors.”

Russians call the Second World War Velikaya otechestvennaya voina, which is usually translated as “The Great Patriotic War,” but perhaps means closer to “The Great War for the Fatherland.” (Properly, it’s the Second Great War for the Fatherland — the first was the Russian repulsion of Napoleon’s army in 1812.) Using the phrase never felt comfortable for me, because it wasn’t my fatherland, and because I didn’t like the triumphalism implicit in the term. But a person in Russia cannot refer to the war without taking sides. Calling it the “Second World War” broadcasts a conspicuous political correctness that irks many Russians, for whom the war represents their nation’s greatest moment on the world stage. The very neutrality of “World War II” aligns the speaker with all sorts of unsavory characters: Hitler apologists, Holocaust denialists, Stalin critics, and anti-Russia propagandists, all of whom are conflated in the Russian imagination. It was their fatherland, their war, and their victory.

If history is written by the victors, one problem with the Second World War is that the victors instantly became enemies. Russian and American history books are products of the Cold War: we tend to downplay the Soviet war effort, and they nearly ignore ours. The American story was clear: Hitler tricked Stalin, then the Soviet Union threw bodies in front of the Nazis until America came in and bailed them out on D-Day. It might be too much to expect historiography of a fourth-grade class, but this narrative was intended to diminish the importance of the Soviet war effort and aggrandize our own. The narrative in Russia is similarly reductive. In Irkutsk, where I studied abroad in college, I took a speaking-practice class with other foreign students. One day, when we were talking about history, the professor said, “And America entered the Great War for the Fatherland on…,” coaxing us into saying the whole date properly.

“Seventh December, 1941,” we obediently chanted, working through the contortions of pronouncing the year in Russian.

“Sixth June, 1944,” she said simultaneously.

We paused.

“Well, that’s very interesting,” she said, and pursed her lips.

She had heard, vaguely, about Pearl Harbor and America’s war with Japan. It gets mentioned in Russian history books in about the same level of detail that American textbooks describe the Russo-Japanese War. D-Day, to her, was America’s entry into to war, and it was purely opportunistic. Before then, we were mostly getting rich selling guns to England and the U.S.S.R. When the Red Army defeated Hitler’s invasion and began regaining lost territory, America rushed to Europe to counter Stalin, worried that he would take over Europe.

There’s some truth to this story. The prosperity of the 1950s in this country would be unthinkable without the upheaval of the war. Our cities were untouched — even the Pearl Harbor attack spared Honolulu — and the weakening of Europe’s powers was key to our ascent. A stroll through our National World War II Museum in New Orleans reveals that our fascination with the war is mostly with military strategy: battle lines, the minutiae of island-hopping, and the logistics of D-Day. Russian museums of the war are tinged with a bone-deep suffering that America can ignore because we have, thankfully, never had to endure it. We learn little about the blockade of Leningrad, the years of starvation and indiscriminate murder in Ukraine and Belarus, the Einsatzgruppen who followed behind the German Army and slaughtered Soviet civilians or shipped them to concentration camps in Poland.

In America, we also tend to devalue the Soviet role in winning the war. Studying the Eastern Front in the West, we ignore the improvisatory brilliance of Soviet military strategy in the second half of the war. Instead, we focus on the battle of Stalingrad, which confirms our story about Soviet tactics: they simply threw people at the problem. Little time is spent on the battles of Narva or Leningrad or Moscow or Kursk, though each was bloodier and more decisive than any American-led engagement, and as strategically important as Stalingrad.

Where our image of Nazi Germany centers almost exclusively on the Holocaust, Russians instead focus on the destructiveness of the German army. When we learn of Lebensraum, the “living space” Hitler thought the Aryan race needed to continue its natural development as a super-race, we tend not to dwell on the fact that Hitler meant the Slavic heartland, where Germans would enslave the inferior Poles and Russians for all time. Russians never forget that. Most gallingly, we learn that Hitler’s advance into Russia was stopped by a brutal winter. As if there didn’t need to be an army of millions to repel them. As if that epic mobilization — the largest in world history — was secondary to some kind of meteorological determinism. As if Russians don’t suffer, too, in the cold.

But in the same way Americans over-simplify the Soviet war effort, Russians overly idolize it. It has become their defining moment, the key to the myth of Russia’s status as a chosen nation, the eventual savior of the world. It is the secular, twentieth-century version of an old Russian Orthodox teaching that the resurrected Christ will appear not in the ancient holy land, but in Russia, there to uplift the Russian people, at last, in a final gesture that will give meaning to their endless suffering by making it redemptive. In his Victory Day speech last year in Moscow, Vladimir Putin said, with tears in his eyes, “Our fathers and grandfathers overcame a powerful, merciless enemy. It was the Soviet people who brought freedom to so many other peoples. It was when confronted with our soldiers that the Nazis were utterly defeated.” It is vitally important to this narrative that the Soviet Union singlehandedly defeated Hitler. The idea that it needed allies, or even desired them, undermines the story. “Allies” is still a dirty word in Russia when referring to the war; it is uttered only in irony. No country — save perhaps the United States — is so assured of its own exceptional status. And just as we are willing to overlook our founding fathers’ shortcomings and sugarcoat the shames of slavery and Indian removal, Russians too easily forget their own horrors.

Josef Stalin provides Russian nostalgia with its greatest obstacle. In reckoning with World War II’s atrocities, Germany has an advantage — if it can be called that — over Russia: Hitler’s villainy is not tempered by being on the right side of history. He was so clearly wicked, so vociferously wrongheaded that mainstream German culture has not struggled with whether or not to distance itself from his legacy. And he lost the war. The association of Stalin with Soviet victory over Nazism inoculates him in the same way that the New Deal helps us overlook Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which put Japanese-Americans in prison camps.

Stalin’s monstrosity far exceeds Roosevelt’s, of course, but so do his successes: he took a backwards country, the one that Karl Marx thought would be the last in Europe to achieve Communism, and turned it into a superpower. In a country where millions hadn’t even transitioned from wood to coal for their stoves, he ordered electricity wired into every apartment, house, and mountainside shack in every city and Podunk town. He projected strength and power in a way that no Russian leader had since Peter the Great, though some have tried. Stalin is Russia’s Abraham Lincoln and their George Washington and more. But he is simultaneously the Soviet Union’s greatest shame, a worse criminal than any American can claim to be, the author of the greatest mass murder in human history.

Unlike Hitler, Stalin did not insist on documentation of his death camps, so we don’t know how many people he killed. Where Hitler’s genocide was obviously motivated by hatred of specific groups, the very enormity of Stalin lies in his lack of specific animus. Estimates of Stalin’s victim count have ranged from six million to sixty million. The margin of error alone is more than a quarter of their population; more than live in the Boston-Washington corridor today; 2% of the entire world’s population at the time. Even assuming the lowest estimate, this slow, nameless killing was comparable to the Holocaust. But without images, without a defined purpose, it can’t capture the imagination. Museums to the purges are small and obscure, not only because they have been actively discouraged by the Putin administration, but also because there is precious little to put in them. Without a record of its specifics, mass murder is too easily answered with a “yeah, but — .” The great killings under Stalin have become an object lesson in the power of narrative and in the impotence of a story without specific details.

Putin was born in 1952, a year before Stalin’s death. He grew up in Leningrad, which was still recovering from its nine-hundred-day siege, the deadliest battle in world history. Reminders of Hitler’s destruction were everywhere, even as the city rebuilt: uncleared rubble in courtyards, tales of starvation and cannibalism, and a shocking gender imbalance: for every 10 women aged 20–29 in 1946, there were only six men. But the 1950s and 1960s were generally good years: the nation crawled its way back to prosperity, Khrushchev loosened the grip of Stalin’s repressions, and Soviet scientists won the space race (don’t get Russians started on this one, either).

The young Putin evolved from what journalist Masha Gessen has called a “street tough” to a gosudarstvinik — a man of the state. He loved spy movies as a kid, so he joined the KGB after graduating from college. After keeping tabs on foreigners for five years in Leningrad, he spent the second half of the 1980s in the KGB office in gloomy East Germany, a representative of the empire that had risen from the ashes of World War II and now commanded an entire hemisphere. Suddenly, all that was taken away. The Berlin Wall fell, which was a bigger deal in the West than in the Soviet Union, but it forced Putin to flee. Then, at the stroke of midnight, as 1991 changed to 1992, the Soviet Union ceased to be. Russians found themselves in a new nation, the Russian Federation, which called itself a democracy and pronounced its allegiance to laissez-faire capitalism. But most importantly, it was impoverished and confused and humiliated. It didn’t have a Constitution, much less a robust national identity.

The rich, predictably, grew very rich, and the poor grew very poor. America claimed the old Soviet sphere of influence as its own, thank you very much. We cheered as the Baltic countries tore down their statues of Stalin and denied citizenship to Russian-speakers, then invited them to join NATO. In 1998, Latvia proclaimed March 16 an official remembrance day for the Latvian Legion of the Waffen-SS, a Nazi military unit (the official holiday was cancelled two years later, but the celebration persists). Barack Obama, in a 2014 speech in Tallinn, praised Estonians for holding onto democratic ideals “when the Red Army came in from the east and the Nazis came in from the west,” as if those things were equal.

The Baltic countries had plenty of valid complaints about Soviet rule, and they were right to align themselves with Europe and America after independence. But any suggestion that Russia should worry about NATO members — explicit geopolitical foes — on its border was met with suggestions to forget the past and embrace the future. When an increasingly impotent and inebriated Boris Yeltsin sold his nation out to a cabal of oligarchs in 1996, causing a crisis of confidence in democracy (Russians started calling it “dermokratia” — crapocracy), that was the cost of doing business. When anti-Russian movements arose in former Soviet nations, Russians were supposed to understand that their neighbors were no longer their concern, but America’s.

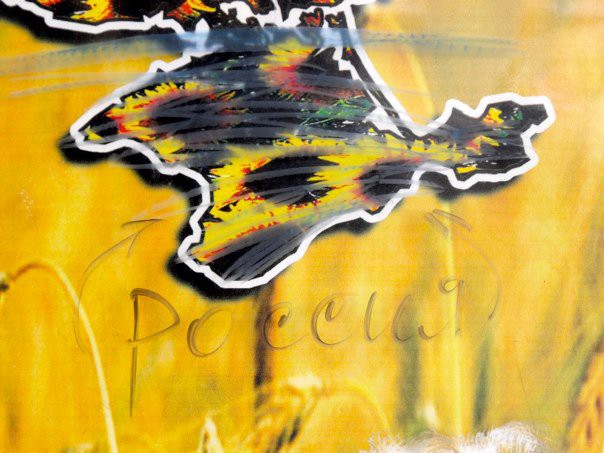

In 1954, when Putin was only two years old, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev gave the peninsula of Crimea to the Ukrainian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic in gratitude for the suffering of the Ukrainian people — outsized even by Soviet standards — under the Nazis. The gesture was mostly symbolic, since the Ukrainian S.F.S.R. was just one mini-state in the U.S.S.R. In March of 2014, Putin took Crimea back. Russians cheered. “Crimea is OURS!” read banners and bumper stickers. Cars lined up on the Russian Black Sea coast for days to take the ferry over to the peninsula and drive its twisty roads. In fairness, Crimea has never really felt Ukrainian. Crimea had not been subject to Ukraine’s language laws, which discouraged the printing of Russian in stores and restaurants. Even government buildings flew the Russian flag. There is no reason to believe that a large majority of Crimeans did not want to join the Russian Federation. The Ukrainians I spoke to in 2014 were angry about the encroachment in principle, but couldn’t really summon the disbelief or rage that Westerners wanted.

To us in the West, the annexation seemed unbelievable. It was so brazen, such a clear violation of Ukraine’s territorial sovereignty. And Crimea seemed an odd prize for Putin. The peninsula is impoverished. What commerce it has is mostly tied to tourism, and an invasion is unlikely to improve its desirability. Western journalists and politicians seemed baffled. Why Crimea? Why now? Four months before the annexation of Crimea, Ukrainians overthrew Viktor Yanukovich, their corrupt and venal albeit democratically elected president, and in early 2014, he fled to Russia. Headlines around the world proclaimed the end of Russian hegemony in Eastern Europe.

“Fascists! Nazis!” cried the Russians to anyone who would hear. Russian television news was filled with reports describing the rise of Nazism in Eastern Europe and comparing the baby-faced politicians of new Ukraine to SS officers. In the West, our news was crowded with images of freedom fighters struggling to get out from under Putin’s dictatorial regime and establish a true democracy. The Russian reaction, if we learned about it, seemed kind of funny, in a smirky way — how could they possibly think that these protesters were fascists? We smirked until Russian troops landed at Kerch in eastern Crimea.

From a Russian point of view, America’s privileged history has made us blind to the fascist menace. Some of us are starting to come around to that view, having watched the political developments of the last year or two, but even in the Trump era, none but the most alarmist of us really thinks that the president is an actual Nazi. But Russians take the term “Nazi” literally, and their reaction to it is based on the sustained presence of World War II in the national consciousness. The Ukrainian uprising was not fascist. If anything, the biggest problem was that it didn’t unseat enough of the old guard to truly change the nation’s path. But the Russian response was not simply paranoia or melodrama.

In August of 2014, I spent two weeks in northeastern Ukraine. Kyiv gleamed, scrubbed of the soot and shit and detritus of encampment and protest. Strung between the birch trees in front of parliament were banners: “Ukraine for Ukrainians!” “Slava Ukraini!” proclaimed massive billboards adorned with pictures of flowing wheat fields, “heroiam slava!” But the ubiquitous expression has sinister overtones to Russian ears: it was the slogan of Stepan Bandera’s private army of nationalists who fought alongside the Nazis in World War II.

Not that antipathy about the Soviet past is all sour grapes in Ukraine. Among other indignities, Stalin likely orchestrated the Holodomor, a man-made famine in Ukraine that claimed the lives of (unrecorded) millions. Ukrainian nationalists have made victimization by Stalin the defining fact of their nation’s modern history. This may seem natural, but it comes at the expense of whitewashing Nazi atrocities, a fact that the Russian media is quick to point out. If Crimea was given to Ukraine as thanks for aiding the fight against Hitler, then could it not be rescinded as punishment for turning back? Most Russians seem to think so.

Putin’s approval ratings, which had been stagnant or even losing ground from 2008–2013, leapt to 80–85 percent after the annexation of Crimea. They have not fallen, even as the Russian economy has weakened. In the West, we tend to scoff at these numbers and disbelieve them, but a growing body of research suggests that these ratings are, in fact, true. Western polls of Russians show about the same levels of support, and no study has indicated that people are lying to pollsters. Most findings show the opposite: the outsized approval is very real. The independent Lavada Center found in a January 2017 poll that 43 percent of Russians reported being proud of “The Return of Crimea.” The only thing that elicited more universal feelings of pride was “Victory in the Great War for the Fatherland,” with 83 percent.

During the Cold War, the United States was as compelling an enemy for the Soviet Union as they were for us, but that era ended in 1991 (and, really, in the early 1980s). Who or what could replace us? Since the 1970s, Moscow has strived to make Islamic extremism into as effective a geopolitical foe as Nazi Germany was. Their war in Afghanistan — which was about as successful as our own and nearly as long — succeeded only in creating dissatisfaction. Lately, Putin has had some success making liberalism into the bogeyman, setting Russia up as a bastion of “traditional” values, opposed to the excesses of Western sin: moral relativism, secularism, and pederasty. But nothing has stuck quite like The Great War for the Fatherland, and the Ukraine uprising, with its overt echoes of Nazism and pro-Hitler guerillas, was just the thing to make Russians circle the wagons.

On April 20, 2017, in preparation for this year’s Victory Day celebrations, Putin spoke at the Kremlin Palace. He extolled the virtues of an “objective study of history,” then warned, “Unfortunately, there are, of course, other ways of approaching history. There are those who try to turn it into a political or ideological weapon.” He continued, “there is an especially dangerous path, taken by certain countries, to valorize Nazism and vindicate Nazi collaborators.” He clearly meant this as a criticism of Ukraine, but then he broadened this focus: “Historical revisionism opens the way to second-guessing the foundations of our contemporary world order and the erosion of the key principles of international law and security, which evolved out of the reckoning of World War II.” That reckoning, of course, created the bi-polar world of the Cold War — when the Soviet Union laid claim not only to Ukraine, but to Syria and others, and when the “greatness” of Putin’s homeland was not in doubt.

In March 2017, The Lavada Center announced that the percent of Russians who proclaimed interest in World War II had fallen from 55 percent to 38 percent in nine years. Statistics like this, often released just before Victory Day, prompt a flurry of hand-wringing. Are kids not learning about the war in school? Is Western propaganda shaping the narrative? Is it because the generation that remembers the war is almost gone? Because kids are too busy on their phones to care about history or sacrifice or what makes them Russian?

These concerns are not just “kids these days” worries; they presume a national identity that is both fragile and rooted firmly not just in the past, but in a particular reading of a single moment in history. As time passes, so too does the immediacy of historical memory. The meaning of victory over the Nazis is, of course, just one facet of the mythically enigmatic Russian identity. But it is at once the most easily identifiable trait of Russian-ness and also the trait that seems most immediately at risk of falling prey to revisionism or “PC culture” or apathy. This part of the Russian self cannot long survive in a changing, globalizing world — a world in which Russian youth, especially in the western regions that hold 77 percent of the population, feel increasingly European and less like inheritors of a great Soviet legacy.

Russian history is a continual cycle of shopping for an identity. A thousand years ago, Vladimir the Great couldn’t decide which religion to adopt, so he sent envoys to the Muslims, Jews, and Christians. When they reported back, the story goes, Vladimir chose Christianity because it allowed both pork and alcohol, and “drinking is the joy of all Rus.” Aristocratic Russians in the 18th century often did not speak their native tongue fluently, preferring to converse in French. If the victory of Nazi Germany fades from its central role in the minds of the new, Europeanized, globalized Russian generation, Russia will adapt. It always has. For now, though, the Kremlin anticipates the biggest, splashiest Victory Day ever. Russians will sing “Victory Day” in the streets till sunrise and after. Tanks and missiles will trundle across Red Square. The Great War for the Fatherland will continue to define the identity of the largest nation in the world.

Matthew Van Meter is an author and lives in Detroit. He is currently at work on a book about a landmark Supreme Court case from the 1960s.

Exercise One, "Nitrogen"

This week is all sharp edges.

I am sorry to be the one to inform you of this if it comes as news, but it is still only Tuesday. Apologies. I hope that in no way prevents your ability to appreciate this song, although I don’t see how it can’t. The folks at Resident Advisor call it “[t]unneling techno cut through with a sharp-edged melody,” and they usually know what they’re talking about, so I’ll just let that stand. Anyway, do try to enjoy.

New York City, May 7, 2017

★★ Birdsong trilled on the side street. The early service was fast but not fast enough to keep the blue outbound sky from being mostly gray on the walk back home. The sun returned, then an even heavier gray took over. The air was cold and the clouds grew dark and lumpy. Busts of rain splatted on the windows. When it was too late to salvage the day, one last interlude of light came on.

Suspicions Validated

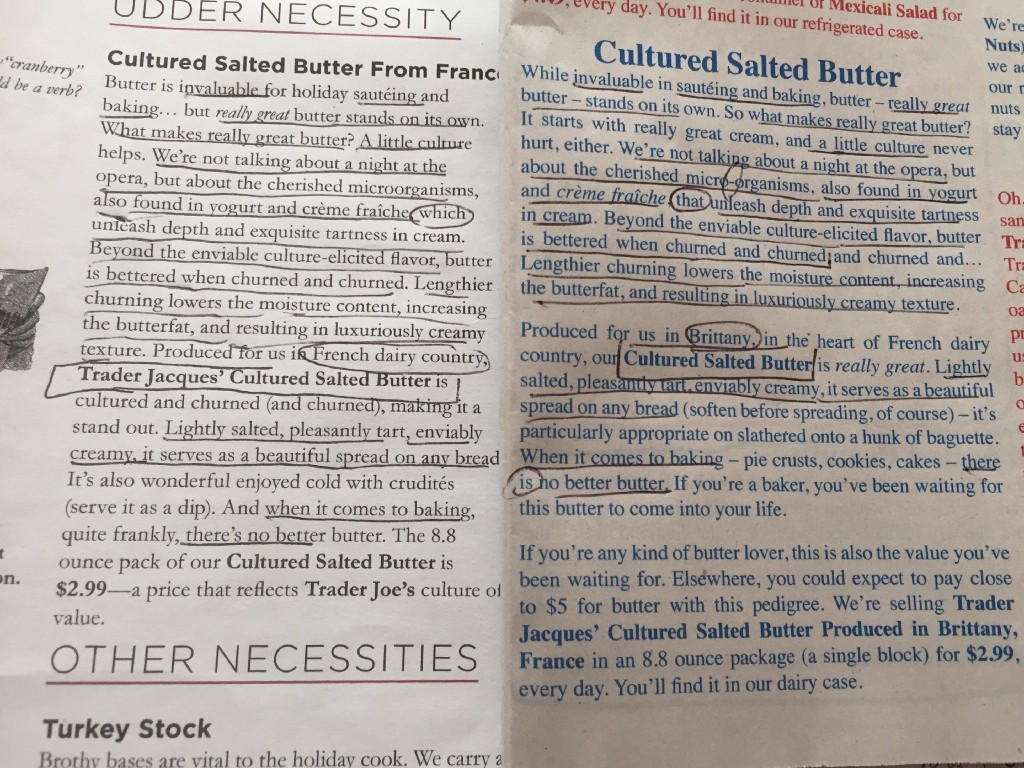

Trader Joe’s is remixing old copy for its “Fearless Flyer”

I told you guys about the cultured butter jokes!!

What’s most amazing here is the subtle differences: “which” vs. “that”; “really great” vs. “really great”; “microorganisms” vs. “micro-organisms”; “French dairy country” vs. “Brittany.” It’s somehow so much better than if the copy had been copied and pasted word for word.

Why Can't We Nap in Public?

An honest question.

What do you think of when you see this photo? Do you admire the composition? Do you identify the landscape at once as Eastern European? Do you think about bears and sectarianism? Maybe. Only later, though. The first thing you think is “That man seems to be very asleep in what seems to be a public place.” Your observations are spot-on. This man was thoroughly fast asleep, doing deep and regular breathing. Our bus stopped at a restaurant near Gospic in Croatia and everyone piled out to smoke and there he was, sleeping in red. When we came out of the restaurant he was gone — probably back to his bus or his truck or his pile of wood. But you are right — he was definitely there sleeping at first. We are all on the same page so far.

After your initial observation, your mind goes to one of two places.

1. What happened to him that he is doing that?

2. Why can’t I do that? I’m not talking about having a small nap on a train, although even that is frowned upon in many places. I’m talking about having a rest. A full-on proper sleep in the day on the side of the road, where you make a pillow under your head and have some dreams. Why can’t I do that? Why don’t I? I’m not saying I want to do that — I am too restless and jittery for naps. I just want to know why I can’t or won’t. I have a naturally curious mind.

If you think a third thing, then I would be glad to hear what it was, but I would say that most of us fall into the two categories outlined above. You either wonder what this man thought he was up to, or you wonder why it is that you yourself are forbidden from getting up to the same sort of thing.

The first question is easy to answer. He was sleeping because he was tired. Life is fucking exhausting.

The second question is harder. If you Google “Why can’t I sleep in public,” you just get a whole lot of vague assertions about how it is one of Western society’s abiding taboos. No one can really give any kind of a good reason for it. According to a Guardian article I read (which called for the removal of the stigma around “urban napping”), sleeping in public signals a loss of self-control “and therefore weakness.” Hmm. This is sort of plausible, on paper, I suppose, until we recall that there is nothing that Western society loves more than complete loss of self-control on all fronts. See: stag parties. Turning over tables in meetings. Drugs. Losing our tempers at the bank. A man I saw once on a ferry in Mexico who felt that someone had jumped the queue in front of him and he just went beside himself, literally hopped from foot to foot, turned purple and screamed that this would never happen in Australia, and we all just stood there, frightened and silent.

Western society is also relatively tolerant as regards weakness. See: the above anecdote. See: complaining in restaurants about nothing, because it is the only means you have of asserting dominance over those around you. Pretending to like someone you do not like, because they are socially useful to you. See prizing your own tedious concerns about personal comfort above the happiness of the group. We love all that stuff. So. What other reasons? How are we to account for ourselves, staying awake all the time like this?

We can say that we don’t sleep in public because it seems dangerous and we will be robbed, and this is sometimes true, but not always. We can say that we don’t do it because it doesn’t seem fun or nice, but I have recently seen more than my fair share of people putting everything they had into being publicly asleep, and they all looked very happy and well-rested.

We can say that people don’t tend to sleep in public because quite a lot of us are women, and there are just all sorts of things that women can’t do without being told to stop. But even this is not the full answer. Not all of us are women. Quite a lot of us are men, and how often is it that you see a man having a hardcore rest in public. Not that often. Not where there isn’t some other compelling reason why he is doing that, like he doesn’t have anywhere else to sleep, or he is wasted. Not where he is a man who seems like he has his own bed, but here he is, stretched out with his hands kind of above his head, doing deep and regular breathing, confident the he will remain undisturbed. It’s just not really an activity that many people participate in. In Croatia it is, though. In Croatia people think nothing of it.

This is what travel is supposed to do, no? It’s meant to broaden the mind and make us question the fictions that constitute our day-to-day. We’re not meant to come home after a trip and tear up the social contract, exactly. More just examine the fine print. What I am saying is that I am only asking these questions because I went on holiday to Croatia and saw people sleeping all over the show, in all weathers and circumstances. They were not doing it because they had to, because they had nowhere else to go. They were doing it because it felt right, because sleeping is amazing and no one would think they were losers if they went for it right then and there. It’s enviable, and it is something the rest of us can learn from. I’m not saying we have to sleep in public. No one can force it upon us. I’m just saying that it’s not out of the question. I’m just saying that you see enough people in public abandoning themselves to the god Morpheus, sleeping like it’s their job, and you start to wonder what the big deal is. You start to wonder what other rules you are doggedly abiding by for no reason other than avoiding the judgment of your idiot peers. What is it that you are not doing even though you would very much like to do it? What are you so scared of? What freedoms are you denying yourself? Why do you care so much about what other people think? Well? It doesn’t have to be this way. Be brave. Go to sleep.

White People Want to Put Mayo on Everything For Some Reason

And answers to other questions you didn’t ask.

“What do white people want?” — Baffled Ben

I’ve been a white person my whole life. Many of my friends happen to be white people. I think I can state definitively that I know exactly what white people want. More episodes of “Frasier.” For Nirvana to somehow get back together. And for mayonnaise to always be spread all over everything for some reason. What is up with all the mayo? Lobster tastes great with butter. Why smother it with mayonnaise? It makes lobster taste like mayo. It’s like putting a Camaro engine in a lawn mower.

It’s not exactly tough being white in this country, but it’s clearly coming to an end. This must be how the dinosaurs felt in the years after the meteor hit the Earth. Kind of anticlimactic. It’s kind of like being 5th-Act Hamlet. At that point, even Hamlet knows he has no future and that everyone he cares about will soon be dead. Might as well go down drinking poison wine and fighting like hell with your poisoned sword. The United States aging out of its white patriarchy, it turns out, is not a toilet fire worth attending.

There hasn’t been a cool white President since Ronald Reagan. And he wasn’t cool. He was just unapologetic, full of swagger and sometimes funny. That Obama guy really bent some white people out of shape. He’s smarter, funnier, cooler and classier than most of us can ever dream to be. If he had been white, there would be elementary schools in every city in America named after him. As it is, he’ll have to be satisfied by being the best President since World War II.

White people want the same things as everyone. Happiness. Power. A Bright Future. Also to feel like they’re winning. Being a Yankees fan is tough. They’ve won the most championships in all of baseball. But they haven’t won a World Series since 2009. And that’s a level of mediocrity they’re just not capable of comprehending. Sure, they went the whole ’80s without winning a World Series. Everybody became Mets fans for a few years in the middle of all that. So it wasn’t so bad. But not winning for a while can be as excruciating as never winning. People who have never won don’t know what they’re missing. People who win all the time do.

Imagine starting a poker game with a huge pile of chips and slowly giving them away over the course of the game. No one wants the game to end, even though it will. Soon white people will be the minority in this country. That’s just math and science, which Americans do not believe in. Most of them don’t read either. Because there is no mayonnaise inside of books.

Should you have a ton of empathy for the plight of White Americans? No, you shouldn’t. You can always visit the National White People Museum whenever that opens up. Or Celebrate White People Appreciation Day, which could be in August, when we could use another long weekend. Until then, it’s probably best for white people to switch from mayo to hot sauce.

Jim Behrle lives in Jersey City, NJ and works at a bookstore.

You Could Use Some Whores. In Your Life

Their new song—“Flag Day”—burns bright.

“There are many places in the world where being a whore is tolerated. Parts of Nevada. Amsterdam, Holland. Congress.” —David Lee Roth

As Trump anhedonia settles into our bones, it’s getting easier to feel like shit and be sad all the time, but anger might be a more effective poison. If you’re feeling defeated and not up to raging against the orange-faced, anti-intelligent, planet-destroying machine, maybe “Flag Day,” a new single by Atlanta, Georgia’s Whores. can be the flame under your blood that sets it boiling again. Lyrically, the song begins and ends with the same chant, “This is a gutter with a flag.” The lines in between that scream of “privileged jowls” and “crooked crowns” make it hard to read this song as anything but a commentary on the dystopian hellscape that is current American politics.

Whores. has been making some of the best heavy music on the planet for the last few years. Their bell-and-whistle-free records and self-sacrificial live shows have garnered attention from every corner of the rock and heavy-metal media since their debut in 2011. “Flag Day” falls right in line with the band’s recent output with production, engineering, and mixing by Ryan Boesch, who has handled these duties for everything the band has done since their breakthrough Clean EP in 2013. The intro is manically dissonant, like In Utero-era Cobain and Grohl on Adderall, with singer/guitarist Christian Lembach screaming his fucking face off like a crazed preacher. The chorus resolves into what has become a signature for Whores. — tone-stacked guitars that make the three piece sound like four or more, and that should make guitars players everywhere rethink their rig. At the break, the drums and bass of Donnie Adkinson and Casey Maxwell, respectively, repeat the previous pounding bridge with washed-out drum sounds that isolate Boesch’s elegant production and engineering.

“Flag Day” is being released as part of the Bash ’17 compilation on the Amphetamine Reptile label (call it AmRep for MaxCred). The long history of AmRep reads like a perfect lineage for WHORES.: Melvins, Unsane, and Helmet. But Whores. venture into the much more wide-appealing territory of hooks and choruses that wouldn’t sound out of place in an arena. The band’s realism and sense of taste is what sets them apart from the more metal-leaning pack that they’re often lumped in with. Crank up “Flag Day” and get your fire stoked while you fight the power, rise above, or board your flight to France.

Catch Whores. on tour now; dates and catalog here.

John Dziuban is no longer a musician. Metal Minutiae is an occasional column on the decline of rock music.

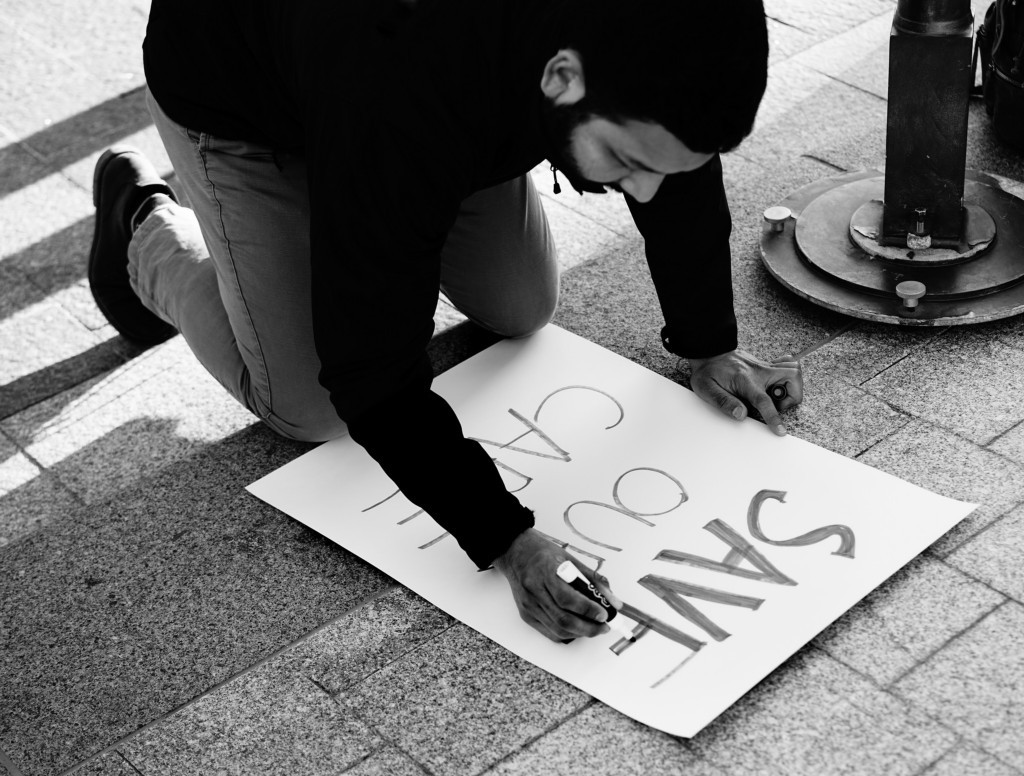

Ain't No Party Like A Propaganda Party

The art of the protest.

America may debate ad nauseam the meaning and legitimacy of our current Administration, but few adhering to any political creed would deny that the era of Trump has officially rejuvenated the art of the protest. The Women’s March in Washington, D.C., in January, was the largest single-day of protest in U.S. history, spawning hundreds of satellite marches in cities across the world, but what set it apart was not just its size but its creative brand of humor. In the months since, social media has been flush with “best protest sign” listicles, turning the language of political dissent into a mainstream battle of wits. Among the highlights from this past weekend’s March for Science were “Rising Seas — Adios Mar-O-Lago!,”; “Got Plague? Yeah Me Neither. Thanks Science!”; and “No Science, No Death Star,” carried by a protester wearing a Darth Vader mask.

“The signs are definitely getting more clever and accessible,” Josh MacPhee told visitors at a recent party hosted by the community-organized collective Interference Archive. MacPhee, who is forty-four and wore a button that bore the accessible, if not particularly clever, message “Chinga la Migra” (Fuck Border Patrol*, essentially), founded Interference Archive along with three partners, in 2011, to document the evolution of D.I.Y. and punk subcultures through the preservation of their ephemera. In other words, the archive, which sits in a one-story warehouse in Brooklyn, looks something like your packrat grandfather’s attic if all he hoarded was oversized serials, zines, vintage videos, and enough shoeboxes of buttons to dam the Gowanus.

MacPhee, who works as a freelance artist and designer, first got the idea of throwing a “propaganda party” after an arts nonprofit commissioned him to make posters about mass incarceration and he ended up with a surfeit of printed material. “I just thought, why not distribute this stuff to people who would rather not go to prison — or to an explicitly political event?” he said. MacPhee decided to throw a party to “reclaim the word propaganda,” at which people could exchange political messages and ideas and “walk away with a roll of stickers.”

While he spoke, MacPhee’s fifteen-month-old son, Asa, waddled by in a printed bandana and a sideways cap. Like his father, the toddler has faithfully attended all five of the parties that have been held so far, which have tackled themes from climate justice to sanctuary cities. Tonight’s theme was “sowing resistance.” “Movements inevitably ebb and flow,” MacPhee said, sipping a beer. “It’s important to create space where people can engage politically where stakes are not as high.” MacPhee watched as his son exploded a bag of rubber bands onto a stack of stencils that read “Eradicate Fascist Vermin.” He added, “In this country, we are so used to an environment where someone else does protesting and you watch it on TV. But here, we want to create a space where the lines are blurred and the pressure is a bit lower.”

Vero Ordaz, a genial labor activist in her mid-thirties, wore four buttons in a row that matched her tie-dyed sneakers. “Stubbornness, curiosity, and a dash of cynicism” had led her to attend the propaganda parties, she said, though she couldn’t recall exactly how many: “I’ve lost my concept of time since this Administration began.” She pointed to a button that read “May Day: Eat The Rich, Feed the Poor.” “Did you know I came up with this?” she said. “Well, most of it anyway.”

A speaker boomed out Bob Marley’s “Get up, Stand up.” A freckly thirty-three-year-old from Sunset Park dropped by to pick up prints that read, in thick black letters, “Oppression Breeds Resistance” and “Sanctuary City!” “My husband is North African and his side of the family is all Muslim,” the woman said. “We met in New York City thirteen years ago. Would we have been able to do so now?”

Despite stiff competition from the screen-printing and block-printing stations, button-making proved to be the most popular activity. “Are you manning this machine?” a visitor asked a young woman with a gelled pompadour and a septum ring. “I’m person-ing it,” she responded. As she helped a pair of women from Indiana print theirs (“Black Lives Matter”; “Femme Love”; “Fire to the Prisoners”), S. J. Avery, a seventy-year-old native New Yorker who was standing in line, recalled her own experience “person-ing” the button-maker at the War Resistance League forty years earlier. “We were anti-capitalism and anti-military, but boy do I still remember those button machines. They were so much heavier,” Avery said, shaking her head. “And you had to screw each individual part separately! Now, it’s so easy now even kids can do it.”

A little while later, a trio of kids did do it. Clutching a paper cutout that read, “Women are Not the Enemy,” Maya, a fifth grader at Park Slope Collegiate, turned to two friends, grabbing the handle bar of the machine, and whispered, “Do I just push this down?” The students had been asked at school to choose an article from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and make a sign that responds to it in some way. Maya described watching Trump’s Inauguration in class. “We were all so upset,” she said. “I stuck my middle finger up at the TV and the teacher didn’t even say anything.” “Omigod, Maya,” her friend Josh, an eighth grader, replied. Then, with a black marker in hand, he grabbed a piece of lime-green paper and wrote in bubble letters: “RACIAL EQUALITY.”

Jiayang Fan is a staff writer at the New Yorker.

*An earlier version of this article mistranslated the phrase “Chinga la Migra” as “Fuck the police.” The Awl regrets the error.

Mr. Mitch, "Black Tide"

It’s Monday, what month is it?

I woke up this morning and the heat was on in my building. The heat! Here in the second week in May! What a weird, wonderful world we live in now. Yeah, I know, it is not actually so wonderful, but can you just go with it for now? Anyway, here’s something blippy-bloopy-plinky-plonky that is not at all unpleasant, which is what I look for of a Monday morning in May when we still need heat. Enjoy.