Bjørn Torske & Prins Thomas, "Arthur"

Ask an older friend what Friday used to mean.

Younger readers will not remember this, but once there was a time when Friday brought with it a sense of joy and relief, drawing down the curtains on the previous five days and allowing you room to breathe and celebrate. No matter how arduous your week had been you knew that come evening you would, even if you had work to do over the next few days, experience some sense of release and freedom until Sunday afternoon, when the dread resumed once more. Of course these days it’s all Monday and Friday at the same time, and your Saturdays and Sundays are spent in a state of shock and confusion, barely allowing you to recover from the beating that the week administered before cranking up the fear and sadness once more — sometimes simultaneous to the recovery. Now we alternate each “What?” with an “Oww,” barely even working up the energy to interject the occasional, “Please, I’ve had enough.” Anyway, happy Friday! Here’s something from the exciting new collaboration between Prins Thomas and Bjørn Torske. Enjoy.

New York City, May 10, 2017

★★★★ It was a big morning for sunglasses. The clouds amid the sunlight were somewhat less than Platonic puffy ones, off-white and a little indistinct around the edges. A bird chirped shrilly and insistently from a lamppost on Fifth Avenue; a river of dog urine spanned almost the entire sidewalk. Uptown was bright and the east was gloomy, each looking like a credible rival portent. The wind favored uptown, but it took a while to prevail. Through all the changes in the light, the chill remained, though a man on Broadway in an untucked pink oxford, chino shorts, and sockless boat shoes did his best to carry himself as if that were not so.

None Of Us Likes It

A poem

Everyone seems mad today, or else they want to cry

I spent the last few hours trying to find the reasons why

It could just be the weather, which is bad and getting worse

Maybe it’s the pollen that the trees all now disperse

And yes, there’s the condition to which no one is immune —

The dread at being held hostage to the whims of a buffoon

You’re sad because you’re jerked around with very little say

Your knowledge of your powerlessness is causing your dismay

In fact, there’s only one thing that is under your control

So please get off the Internet, it’s poisoning your soul

The Old Monuments

Watching the Confederate statues come down in New Orleans.

Most evenings after six or so, the crowds in front of New Orleans’ Confederate monuments settle into a lull. Sometimes it’s six or seven stragglers. Sometimes it’s a couple and their dog. They bring wrinkled Confederate flags, and Mississippi bandannas, and sometimes a handful of American ones too, and since Louisiana is open-carry they’ll flash the pistol on their belt, posted up and shouting at random passersby into the night. A lot of these folks are local, but a good chunk of them aren’t. Nobody seems to know what to do with them. Mostly they’re left alone.

The first monument was erected in the late 19th century. There’s one of Robert E. Lee, and one of General P.G.T. Beauregard, but the Jefferson Davis and Battle of Liberty Place monuments are gone. Police escorts assisted with their removal in the middle of the night. The first round took place on April 24th, and the second happened after midnight on May 10th, and the city isn’t saying when the rest will follow. They swear it’ll be sooner than later.

The campaign to bring them down picked up steam in late 2015. Mayor Mitch Landrieu deemed the statues as public nuisances. He signed an ordinance calling for their removal. But the first company that came forward to assist with that was deluged with death threats, and then the next one afterwards, and then the next one after that, and then, for a while, it looked like they actually weren’t going anywhere after all.

Last month’s first after-hours removal was a jolt and a shock. Before the Liberty Place structure came down, some protestors held a candlelight vigil. They really looked like they were mourning. A couple held actual candles. But most of them were fucking around on their phones. And that insistence on the preservation of bigotry might sound consolidated and condensed, but New Orleans is actually steeped in it; it’s interpreted as a jutting branch of Southern romanticism.

Of course you’ve got the Deep South factor, but the dog whistles are blasting all over the city; in fact, a few years back, Dillard University literally hosted David Duke on its grounds for a Senate debate. But about a week ago, I was biking through Mid-City, where the Davis monument loomed, when I nearly collided with this white lady riding one of those babyseat-bicycles. We both stopped and apologized. Her kid sort of wagged his hands at me. We rode for another two minutes in silence before we ended up in front of a protestor.

He wore an over-large “Don’t Mess with Texas!!!” hat. He had those flags with the snake in each hand. He looked totally, wholly prideful, absolutely lost in his cause — and, for the briefest of moments, I actually tried to have a slither of empathy. But then the lady in front of me cleared her throat, and she spat on the grass beside him.

You need to go the fuck back home, she said. Her kid and I made the same face.

You are not from here, said the mother, and you need to go the fuck back home.

Since the city isn’t telling us when they’re bringing the next statue down, the consensus seems to be that it could happen any night. So depending on which of the remaining monuments you show up to, and when you show up, you might find a modest crowd of squatters policing the grass just beside them.

One afternoon around Jazz Fest, a small tussle enveloped the Beauregard monument. Observing from the outside, the group looked mostly white, but there were a handful of Latino people, and one or two Asian folks in the thick of things. I didn’t see any black bodies in the mass — they were standing on the periphery. Almost instantaneously, the cops started converging, and the group damn near dissolved entirely.

The people left started to shift, looking more than a little antsy. The deep looks we’d been giving each other turned into something a little closer to kinship. One white lady I talked to said she was out here for support. She was in town from California. One white guy said he was out here because it he felt like it was his duty, and the white guy beside him, probably his buddy, said it was the least that they could do. Two black women stood by the streetcar, a younger lady and someone who looked like her mother, and when I asked what she was doing she looked at me through her shades, and then what she did was laugh. She said she was only watching.

Another afternoon, a few days later, around the same monument, I ended up staring at it next to this older white guy. We ignored each other for a while, and then he sort of looked me up and down. Eventually, he told me that he was a local. He was hoping the mayor would come to his senses and leave the statues alone. He said told me that the monuments were history, that the city was destroying history, and we all knew what happened when you forget the things that you’ve done. He asked how I felt about the other statues, ticking them off one by one, and did I know that each of those individuals was integral to New Orleans, that they were regal institutions. He asked me if I thought that history was worth preserving. He asked how I felt about each of those statues.

A month earlier, I’d been invited to the Beauregard-Keyes House, which is a sterling, glossy residence, square in the French Quarter. After a couple hours’ worth of drinks, more than one acquaintance made it a point to tell me that the General was “a good Confederate.” He was compassionate, they said. He cared about black people. I nodded and smiled and fought the urge to piss all over their floor.

I told the guy standing beside me that the statues were pretty shitty. He looked disappointed in me. The conversation was over.

For a little while, we watched a group of protesters shout each other down. One guy was bearded, big and tall, and the others were an Asian couple in vacation garb. The two men toed the line towards one another, but neither of them did anything physical. They looked a little like a parabola, getting just close enough for something to happen.

This past weekend, there was a rally championing the dissolution of these monuments, and hundreds of people showed up. The march started in the Quarter, before snaking downtown, until it ended up in front of the structure by Lee circle. The photos were all over my feed. I saw pictures of reunions taking place, and pictures of signs that had been made. Every other person was smiling. It looked like something had been accomplished.

And then, three days later, it was. Around eleven on Wednesday night, my phone let me know that the elementary schools surrounding the Davis monument had been put on notice. The next one was coming down. It didn’t take long for the crowds to develop. They started small, until they weren’t anymore, and every now and then the cops stepped in to separate the clusters. When the statue was finally lifted, there boos and cheers and boos. Friends posted selfies with the monument in the background, behind backdrops of oversized Confederate and flags. A few banners streams in the foreground, claiming they’d make the country great again.

The next morning, a buddy texted me to ask what had changed. The statue’s gone, he said, but there’s always something else. And if you’re driving down Jefferson Davis Parkway, the monument’s gone, but that platform’s still there, right along with the ground on which it stood.

There’s been a lot of talk that it’s New Orleans’ commitment to diversity that’s bringing these statues down. And that could very well be true. But the white supremacy’s still there. It’s deeply ingrained in the city’s foundation, in its draconian incarceration policies and its segregated housing and a commitment to commodifying who gets what quality of education. New Orleans has a lot of different people, from a number of different places, but it would suck if that diversity overshadowed the fact that it’s a majority black city. And in this majority black city, the black people are being priced out. The black people aren’t given loans. The black people are cordoned to the outskirts of the affluence. The black people are subject to food deserts, and the black people are jailed at astronomical rates; but now, the black people won’t have to drive past statues of white men embodying a time when black people weren’t considered people at all.

Once the final statue’s carted off, black people will continue being treated like black people in New Orleans. There will still be poor people when the statues come down. Families will continue to be priced out when the statues come down. Even still, that’ll keep happening, the structural change that’s needed still isn’t forthcoming, and it will do us good not to hold our breath until it does.

But, for now, the statues are coming down. We’re really going to do it. We might be sleeping when they go, but in the morning they’ll be gone.

The 1970s Are Back In A Big Way

Reminder: they were not good.

A body was pulled from the lake in Central Park on Wednesday morning, less than 24 hours after another body was found floating in the park’s reservoir. Police officials said the second body — discovered in Swan Lake, near East 59th Street — belonged to a male in his 30s. The man was clothed except for a shirt, and his body showed no obvious signs of trauma. The medical examiner will determine the cause of death, though officials say the corpse could have been in the lake for at least a week.

First came Trump’s “Nixonian” firing of James Comey, now we have not one but TWO dead bodies found in Central Park bodies of water? Bring on the sailor pants.

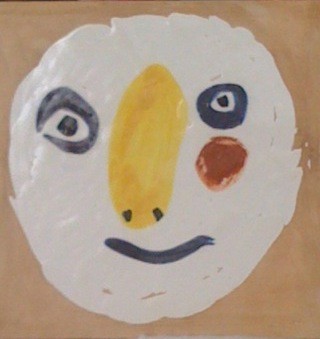

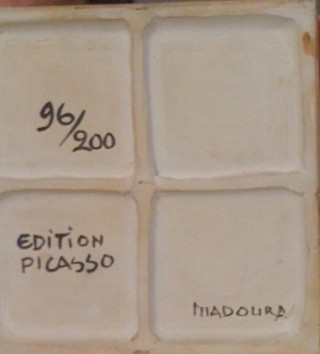

The Picasso In Her Closet

My mother was dying, so she couldn’t hold on to Ann-Marie’s Picasso any longer. I should tell you: this wasn’t Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It was a small square tile — one of Picasso’s Madoura pottery pieces and part of a series of two hundred, according to its back. On the tile’s surface was a simple human face: loop eyes, slash mouth, yellow pickle-ish nose, single red blob suggestive of a cheek, all set on a plate-like white circle like a hastily prepared meal. By Picasso, though.

My mother was holding on to the Picasso for her childhood friend, Ann-Marie (this isn’t her real name), who had told her that she had multiple chemical sensitivity, a physically debilitating reaction to what she considered toxins in the environment. Online there’s an intricate support network of MCS sufferers of which Ann-Marie became a part, but there also exists a grousing community of doubters who think that MCS is a manufactured malady.

The American Medical Association and the World Health Organization don’t recognize MCS as a bona fide illness, and neither did my mother. She forwarded me, her only child, some of Ann-Marie’s emails about living with MCS, including one from 2007 in which she complained of electromagnetic frequencies, which she said made it hard for her to use her cell phone. At the top of Ann-Marie’s email, my mother had written this to me:

See her message. I honestly don’t know what to say to her. I think she is a nutcase. Maybe just go along with her and be sympathetic like we did when my mom had dementia.

Later she emailed me,

Ann-Marie was pre-med in college, and I want to ask her what empirical evidence there is to support her electric sensitivity diagnosis. What causes it? What specific symptoms? What is the correlation?

For Ann-Marie, having MCS eventually meant being peripatetic, by which time she asked my mother to mind her Picasso. Ann-Marie’s parents — her father had been a wine importer — had purchased the piece as an investment; they’d had only one child, and when they died, it was hers.

I first saw the Picasso when Ann-Marie showed it to me at her West End Avenue apartment in the mid-1980s — this was well before her MCS self-diagnosis. My mother and I were down from Boston to look at prospective colleges for me. She and Ann-Marie, who was in advertising and had done a L’eggs commercial that I’d actually seen on TV, had met when they were twelve, at a camp in Maine about which they were jointly evangelical their entire lives. I’d hated camp, and being as outdoorsy as Lovey Howell from Gilligan’s Island, I was hell-bent on an urban school.

Columbia didn’t want me and Barnard wasn’t sure, but NYU said they’d try me, so I moved into a Greenwich Village dorm in the fall of 1985. Occasionally Ann-Marie invited me over for dinner. She was divorced and hadn’t had kids, and her single life interested me more than my likewise single mother’s did. Ann-Marie lived alone in a high rise in a two-bedroom, two-bathroom marvel of tidiness with a postcard-worthy view of midtown; she was right around the corner from the Tower Records where Woody Allen and Dianne Wiest seal their fate in Hannah and Her Sisters. One night, Ann-Marie made me dinner and told me about her dating life, and that some guy she was seeing only wanted to “jump my bones.” The expression, which I’d never heard before, rang in my ears.

My mother said that Ann-Marie saw herself as an artist, which was why, when her building went co-op, she decided to stay on as a renter, refusing to purchase her unit even though her inheritance would have made it possible. Her reasoning was along the lines of “A truly free spirit wouldn’t own property.” This decision infuriated my pragmatic mother, and even I, who didn’t consider myself a grown-up yet, registered a self-sabotagingly bad call.

To me, Ann-Marie didn’t seem like an artist — she dressed in the earth-toned tweeds of the advertising executive she was — but of course there was a creative aspect to her job, and she did have cool artwork hanging on her walls, starting but not ending with the Picasso. The last time I was at her place, before my social life at NYU perked up, I saw something new: a series of about a half dozen vertical canvases on her living room wall. One canvas was sheathed in what looked like a light-blue pillowcase. Another featured part of a paper bag. One may have been completely blank. “Do you like them?” Ann-Marie asked me, and I truthfully told her I did. I’d taken to poking around SoHo galleries, and I thought that much of what they were selling was less endearingly peculiar than these pieces.

After I left Manhattan in 1990, my mother wasn’t as likely to visit Ann-Marie as Ann-Marie was to visit my mom in Massachusetts, and if I was living in the state I would pop over. They would trundle out the camp songs, and I would roll my eyes, which was what I assumed they wanted from me. One time Ann-Marie came up to visit my mother with the express wish to see the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, but before she left town she told me in private that my mother had reneged on taking her. Ann-Marie was supremely miffed, which thrilled me. For a flash, she and I were the girlfriends and my mother the odd woman out.

That was Ann-Marie’s last visit to my mother’s place as a healthy person, and probably the last time I saw her. She gave up her West End Avenue apartment, in which she said she felt sick. Because of her inheritance, Ann-Marie could afford to stop working, and she began to search for a home that wouldn’t feel toxic. She tried living in Texas, and maybe some other state, and also here in Massachusetts; they were all botches. She must’ve entrusted my mother with the Picasso sometime before my mom’s first go-round with cancer. Along with the Picasso, Ann-Marie gave her the phone number of some friends, a couple who lived in Connecticut, who could take custody of the piece if for some reason my mother was no longer able.

I suspect that my mother regarded Ann-Marie’s embrace of the MCS party line as something of an upper-middle-class luxury. Once, lamenting Ann-Marie’s lifelong unhappiness, my mother told me that Ann-Marie had been kind of a spoiled little rich girl — she’d even owned a horse. This dig might seem galling coming from my mother, who, like Ann-Marie, grew up rather well-to-do in New Jersey. But my mother probably had a low threshold of tolerance for people nursing can’t-quite-put-a-finger-on-it ailments given that her father committed suicide when she was away at college; if anyone deserved to indulge a psychosomatic illness, if that’s what Ann-Marie had, it was arguably my mother. But she was too practical for that, and anyway, from pretty much the day she divorced my father until the day she retired, she had to work.

Because of the Picasso’s value — to Ann-Marie, sure, but also to the art world — I was apoplectic about how my mother was storing it: swaddled in a blanket in a Crate and Barrel shopping bag. She kept the bag in her storage unit on her floor in her apartment building in Watertown, Massachusetts, and once, after she’d been rearranging things in there, she forgot to put it inside the storage space, so it spent the night in her building’s common hallway. This is a Picasso I’m talking about.

I kept telling her there might be something on that blanket — bleach, maybe — that could erode the surface of the tile, and that there was an entire industry devoted to preserving artwork; we could tap it. One day my mother phoned me to say that she thought I was being controlling on this point and that the way she was storing the Picasso was just fine. I think she thought I was being like Ann-Marie: seeing toxins where there weren’t any.

This was likely our last fight. In 2009, at around the time I contacted a friend at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts about getting advice from professionals on how to store the Picasso, my mother’s cancer came back. She summoned the Connecticut couple.

As cancer whittled away at my mother, Ann-Marie, too, got a cancer diagnosis. She outlived my mom by not quite two years, during which time we occasionally spoke by telephone; she was now living in Dallas, giving Texas a second shot. I’m an anxious telephone talker, but these conversations I liked, both for the obvious, wounded-motherless-daughter reason and because Ann-Marie and I seemed to get each other in a way that my mother, who tried valiantly, never got me, and maybe Ann-Marie’s parents never got her. After I learned of Ann-Marie’s death — her dispersed MCS community of friends had been kind enough to include me in their email chain — I was ashamed of myself for wondering this: might Ann-Marie have bequeathed the Picasso to me?

Of course she hadn’t. Why should she? Ann-Marie was an admirably charitable sort, and I was no charity case. (Recall that my deceased mother, while plenty charitable herself, had been practical, which meant she was a saver, and that I was her only child.) I assume that if Ann-Marie didn’t donate the Picasso, any proceeds from it went, as well they should have, to a favorite cause — environmentalism or animal rights, say. Or to the camp in Maine, which informed me that Ann-Marie, no longer what anyone could call spoiled or rich, had made a substantial contribution in my mother’s name shortly after my mom’s death.

I learned from Ann-Marie’s MCS friends that after she died they found among her possessions many notebooks and journals, some containing her poetry. I’m guessing that she had long ago gotten rid of the canvases she had hung on her living room wall on West End Avenue, and that no one had seen any value in them. At some point after I left New York, my mother told me that it was Ann-Marie herself who had made them — she had admitted this to my mother, but not to me. This smarted. My mother didn’t even like that sort of thing — she liked Manet and Monet. She liked pretty things. Did she even like Picasso? Had I known that Ann-Marie made those pieces, I would have told her that I thought she was on the right track — “Good for you,” or something. What I would have meant was, “Go ahead — be an artist! Give up advertising! You don’t have to get sick to become a free spirit.” As if anyone in adultland would have listened to me.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor. She writes occasional Best Forgotten columns for The Awl.

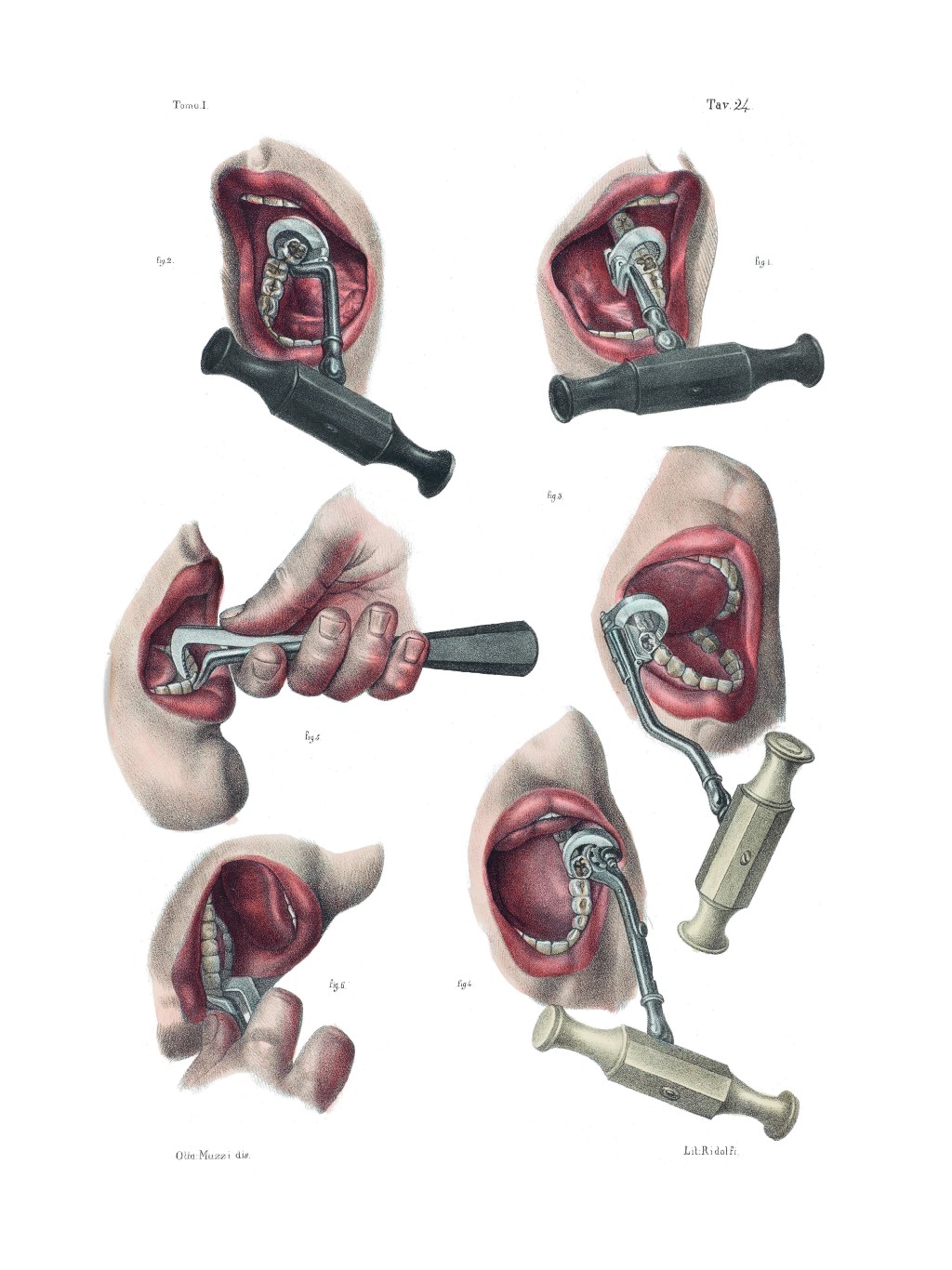

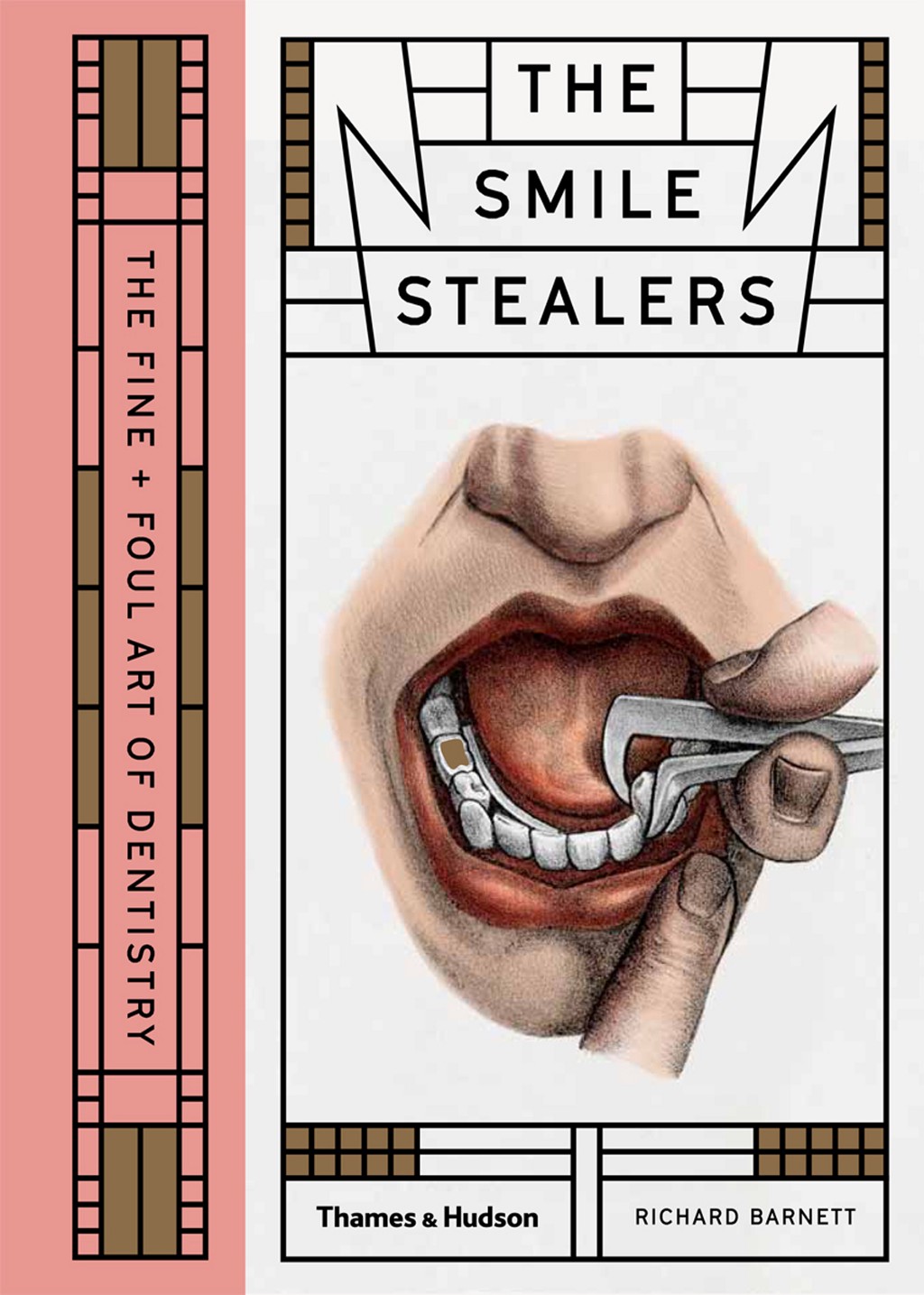

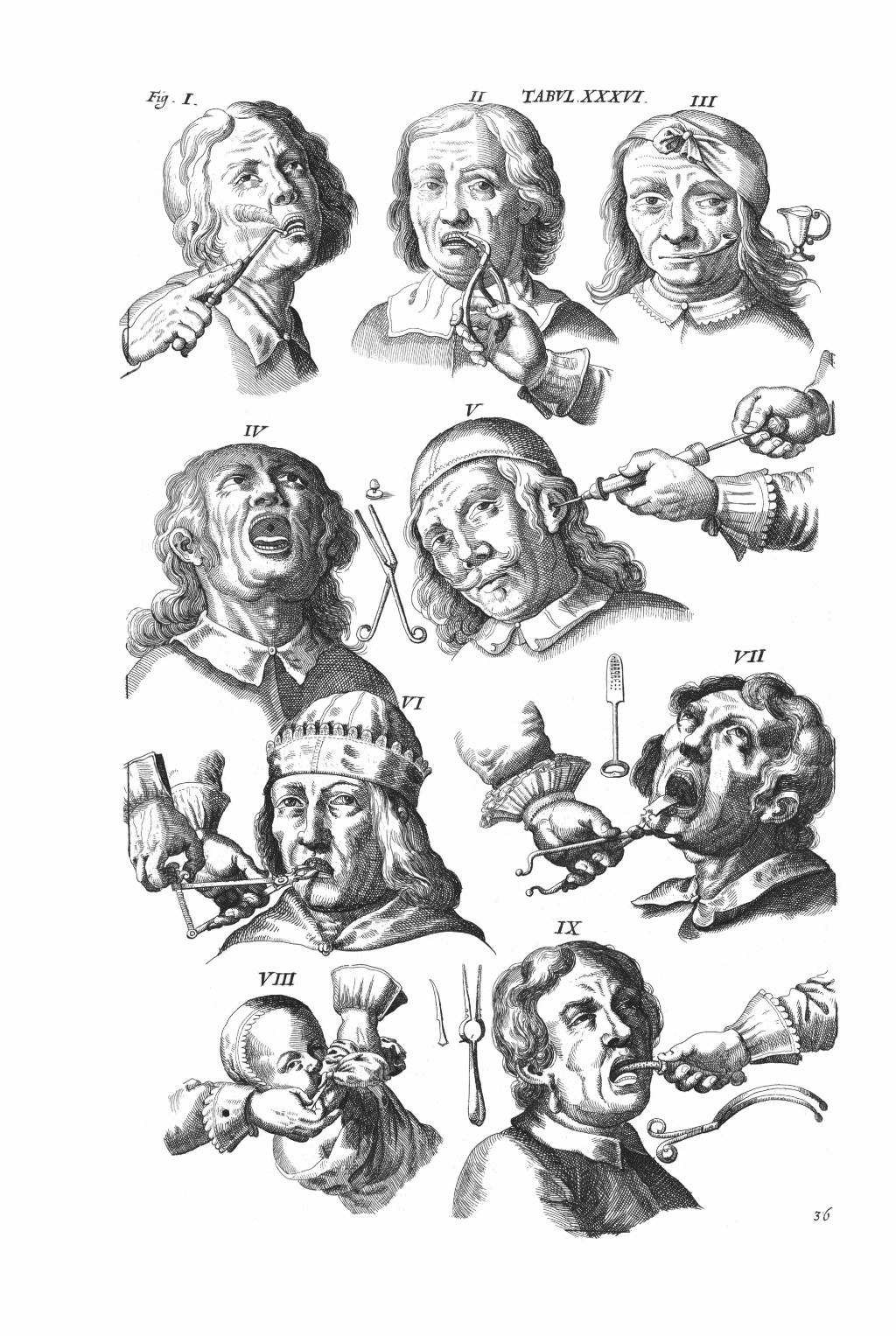

Open Up and Say AAH!

Dentistry is vile

Long before electric drills and saliva vacuums, we’ve been wary of dentists, and for good reason: the history of what we now call “oral health” is well, rooted, in thousands of years of discomfort, violence, and fear. (It’s not for nothing that Steve Martin sang about parlaying his adolescent penchant for inflicting pain and suffering into a career in dentistry in 1986’s Little Shop of Horrors.) The patron saint of dentistry — yes, there’s a patron saint of dentistry — St. Apollonia only became so after a mob of religious men bashed in all of her teeth and threatened to burn her alive (this was Egypt in the second century AD). In medieval paintings and stained glass, St. Apollonia is typically pictured with a pair of blacksmiths’ pliers — the instrument long associated with traumatic tooth extraction.

How else to rid oneself of the malevolent tooth worms believed to cause decay? In early Chinese medicine, you might have tried this home remedy:

Roast a piece of garlic and crush it between the teeth, mix with chopped horseradish seeds or saltpetre, make into a paste with human milk; form pills and introduce one into the nostril on the opposite side to where the pain is felt.

In second-century Rome, the leading physician prescribed pickled chrysanthemum root as a palliative. Wiser doctors suggested opium.

But yanking those putrid incisors was the only viable long-term solution, prompting a visit to the village blacksmith, with his handy pincers, or perhaps to the cooper, given that the hooked ‘pelican’ tool preferred by medieval tooth-pullers “originated as a device for pressing iron hoops onto barrel staves,” according to Richard Barnett’s The Smile Stealers: The Fine and Foul Art of Dentistry. “Patients sat on a low stool, their head held between the tooth-puller’s knees, while he locked his pelican onto the offending tooth and sought to unseat it.” Alternatively, he might try the ole dental key, a “cross between a corkscrew and a door key” that tightly gripped the offensive bicuspid while the pseudo dentist twisted and turned as if “opening a lock.”

These are the kind of squirm-inducing trivia one picks up while reading Barnett’s newest book, the third in his unofficial “tr-ILL-ogy” of copiously illustrated and elegantly designed medical histories, following Sick Rose; Or, Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration (2014) and Crucial Interventions: An Illustrated Treatise on the Principles & Practice of Nineteenth-Century Surgery (2015). Like its predecessors, The Smile Stealers is a quirky and fascinating book that shines a spotlight on London’s eccentric Wellcome Collection, from which the gruesome imagery is sourced. All three might be fairly marketed as coffee-table books for the slightly twisted.

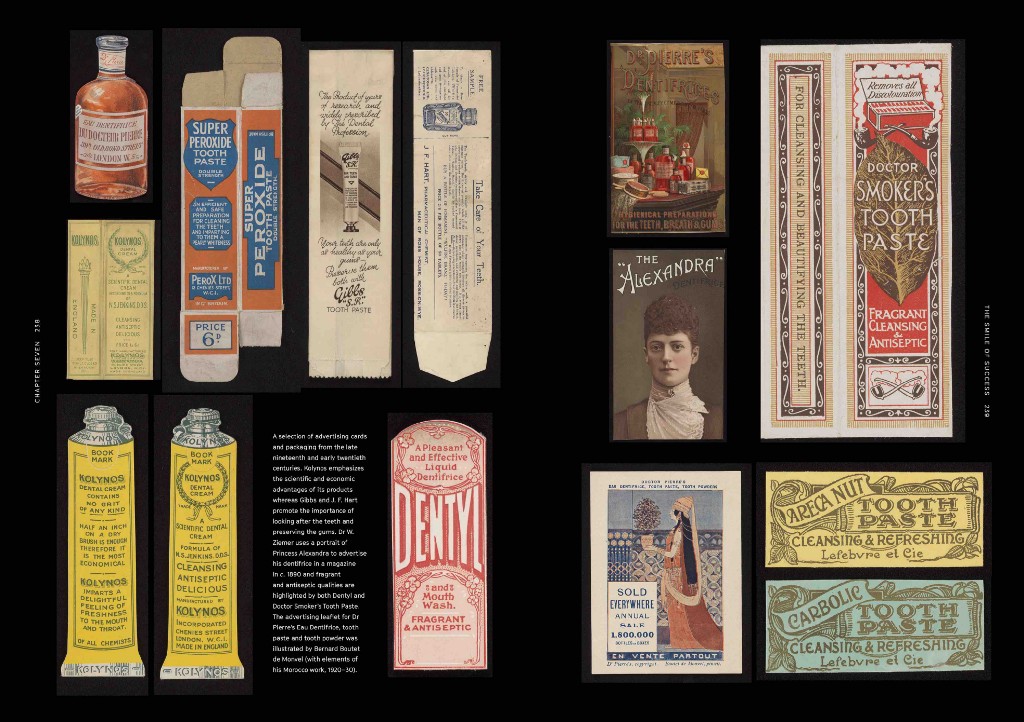

The 350 illustrations appearing in full spreads and peppered throughout the text are central to the book’s grotesque charm. They range from reproductions of oil paintings to anatomical engravings to archival images of patent medicine packaging to photographs of archaic dental instruments and hardware. Perhaps because of the distance afforded by modern medical technologies, anesthesia chief among them, The Smile Stealers is genuinely fun to read.

We get a glimpse of the “most famous false teeth in history,” which belonged to George Washington, and were NOT made from wood. The lower plate holds human teeth — harvested from a cadaver or a pauper — and the upper chiseled elk molars. “In another setting they could be a pair of castanets imagined by Francis Bacon — a ghastly, disembodied grin that might pursue you, gnashing, through your dreams,” Barnett writes. Washington’s spare pair, he adds, was constructed of walrus ivory, a.k.a. ‘seahorse teeth.’ Vexed by smelly, uncomfortable dentures, it’s no wonder the first president was known to be a wee bit prickly.

Despite the reputation of dentists, several lively characters emerge in Barnett’s studious yet sprightly narrative. One is Jean Thomas, la perle des Charlatans, an eighteenth-century Parisian tooth-puller who literally wore a feather in his cap. As Barnett writes,

Myths multiplied around this Rabelaisian figure: he weighed as much as three men, he ate as much as four, and if a tooth proved obdurate he would rock his pelican onto it, lift his client off the ground and allow their own weight to perform the extraction.

Sometimes the jaw came with it. Thomas’s nemesis, Pierre Fauchard, the “first practitioner to call himself a dentiste,” wanted to professionalize dental care in the same way that surgeons had, once they stopped moonlighting as barbers. Fauchard tried to convince folks that if they cleaned their teeth regularly, they would suffer fewer toothaches.

It took a long time for that crazy notion to catch on, and in the meantime, turn-of-the-twentieth-century showmen-dentists like Painless Parker, continued to dose patients with whisky and cocaine and pluck their pearly whites. Parker claimed to have snatched as many as 357 teeth in one day, and he wore his plunder, like some kind of maniac, on a handcrafted necklace of human teeth (which, by the way, is something you can actually buy on Etsy). A Canadian who had relocated to Brooklyn, Parker advertised himself as “Painless Parker, Preeminent, Par excellent, Positively, Painless Perfection of Practice and Philanthropically Predisposed to Popular Prices!” He relished alliteration like a Ringling ringmaster.

Barnett steers clear of the orthodontic-industrial complex, which might have made for an interesting addition to his final chapter on America’s obsession with “the smile of success.” Ensured by daily upkeep (and the associated products), preventative check ups, and fluoridation, a flawless set of choppers manifested health and wealth in postwar America. Fair enough, but what about enforced beauty norms and the role of cosmetic dentistry? The twenty-first-century desire for bleached teeth, for example, is just as bizarre as tribal teeth sharpening or the capping of canines for a more fang-like appearance, known in Japan as yaeba teeth.

Though we may still dread dental appointments, The Smile Stealers reminds us, above all, not to be such cowards. Today’s skilled practitioner will likely refrain from pulling so vigorously on your rotten molars that he tears a hole in your palate that causes liquid to spill from your nose “like a fountain” every time you take a drink, and which can be fixed only by cauterization with a hot iron. At least not without offering you laughing gas first.

Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places. She has written about books and history for Slate, The Guardian, LitHub, and elsewhere.

The Awlcast, Episode 12: Flipper

Talking about dialing with David Obuchowski.

This week’s episode of the Awlcast is a special edition, written and recorded by David Obuchowski, the author of “Dial D for Dolphin,” a story about the mystery behind a spam caller he dialed back. Maybe you read it? It’s a story about phone calls, but it’s also about stories, mysteries, and what we want to believe about both. This is the audio version of his story, complete with dolphin trills.

A friendly reminder to register your number on the Do Not Call registry, not that that really helps these days. Good luck out there.

A Poem By Natalie Shapero

Tomatoes Ten Ways

On a lampless arc of interstate, playing

I DON’T SPY, the nighttime game

where you say what you don’t see and wait

for someone else to also fail to see it —

are we there yet? I just want to get

back now, back to my hollow, back

to my shelf and mattress and electric

oven where decades of hands

have worn the temperature marks

clean off the dial — it’s always a guess.

Cooking is important. It prepares us

for how to sustain each other

in the emptiness ahead. Bruschetta

for sharing made from strips

of garbage. A novel kind of starchy pie

baked over one tea light. Children,

today was sent here by the future

to beg you to think of your country

like a body — it is only yours

for now. It is only a matter of time

before it buckles and kicks and ousts

you and sinks, like the very

body it is, right back to the ground.

Natalie Shapero is the Professor of the Practice of Poetry at Tufts University and an editor at large of the Kenyon Review. Her poetry collections are Hard Child and No Object.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Penguin Cafe, "Ricercar"

Remember when it mattered what day it was?

Here is the lead track from the new Penguin Cafe record, which is one of the few things that brings me joy these days, to the extent that I am able to experience joy at all. As is the case with everything your own appreciation will not doubt differ based on personal history and aesthetic preference but I hope it is able to bring you even a small amount of the pleasure I have found in it, which, as previously mentioned, is an amount always mediated by my chronic inability to feel much of anything other than numbness and the overpowering sense of futility that these days carry with them in every waking moment. Enjoy.