Luca D'Alberto, "Endless"

Everything is.

I know what you were thinking, but no, sorry, it’s Thursday. There is so much more nonsense ahead before we even see the slightest hint of weekend. May God have mercy on your soul. Anyway, here’s some neoclassical whatever from Luca D’Alberto. Enjoy.

New York City, May 30, 2017

★★ Roses bobbed on a fully laden bush. The greenery glowed intensely in the dimness of morning. The clouds stood just low enough to snip off the spire of the Empire State Building. Downtown, with no growing things in view, the scenery was the color of spent charcoal. Past lunchtime, the sameness was broken for a while by a dense, forbidding rain. That passed and the new rainfall was absorbed in the damp, monotonous gloom.

Odd Lots: Curious Objects Up At Auction

A Playboy Bunny costume, Manhattan sewer maps, and a class photo from the 1850s

Lot 1: Piece of (Cotton) Tail

Ah, the Playboy Bunny, a hybrid female human/rabbit species dreamed up by Hugh Hefner, who opened his first Playboy Club in Chicago on February 29, 1960. Her natural habitat is a smoky club full of paunchy, middle-aged men.

Seriously, we’re talking about women dressed as sexualized woodland creatures. Bedecked in a strapless satin bustier-leotard, complete with a pair of matching bunny ears and a fluffy white tail on her backside, the Playboy Bunny served food and drink to an “exclusive” group of randy men-about-town. All of this fizzled out in the 80s, although it was announced earlier this year that the Playboy Club and its Bunnies (with “updated outfits”) are planning a comeback in NYC. #MakeAmericaGreatAgain

The green vintage costume seen here would have been chosen to complement the skin tone of its owner, Suzanne, sometime in the 1960s. Seldom seen complete with the nametag, cufflinks, clip-on bowtie, etc., this uniform hails from the Playboy archives sold at auction in 2003. It’s back on the block in California on June 8, where some big spender might snatch it for $8,000–12,000.

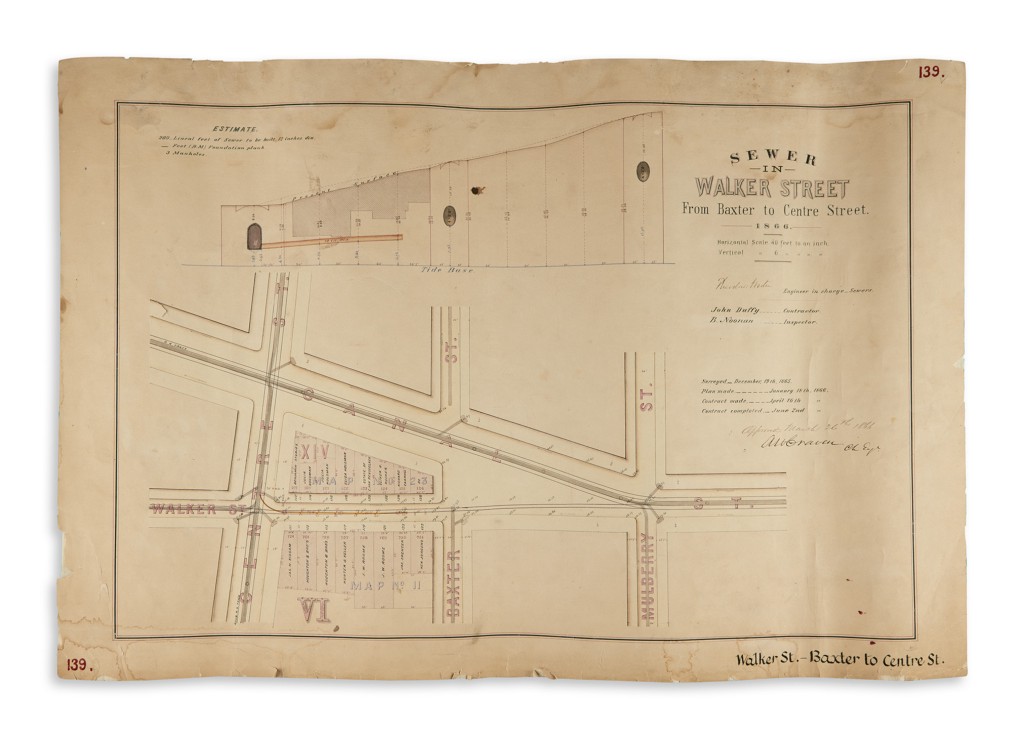

Lot 2: Where the Sewage Ends

Want to take a deep dive into Manhattan’s sewers? Here’s your chance to do so, without mucking up your shoes or confronting a rogue alligator. At auction in New York on June 7 (and on view until then) is a set of nine hand-drawn maps of lower Manhattan’s subterranean sewer network. Dating to the mid-nineteenth century, the architectural plans mainly focus on the streets surrounding the modern area of the entrance to the Holland Tunnel, plus two near the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, and one in Little Italy.

There was a time in the New York City’s history when sanitation services barely contained the mess — Canal Street, for example, was once a slow-flowing, foul-smelling stream of polluted wastewater until it was paved over. These maps attest to the city’s attempt to improve the system.

The auction house estimates that these funky ink and watercolor maps will make about $5,000.

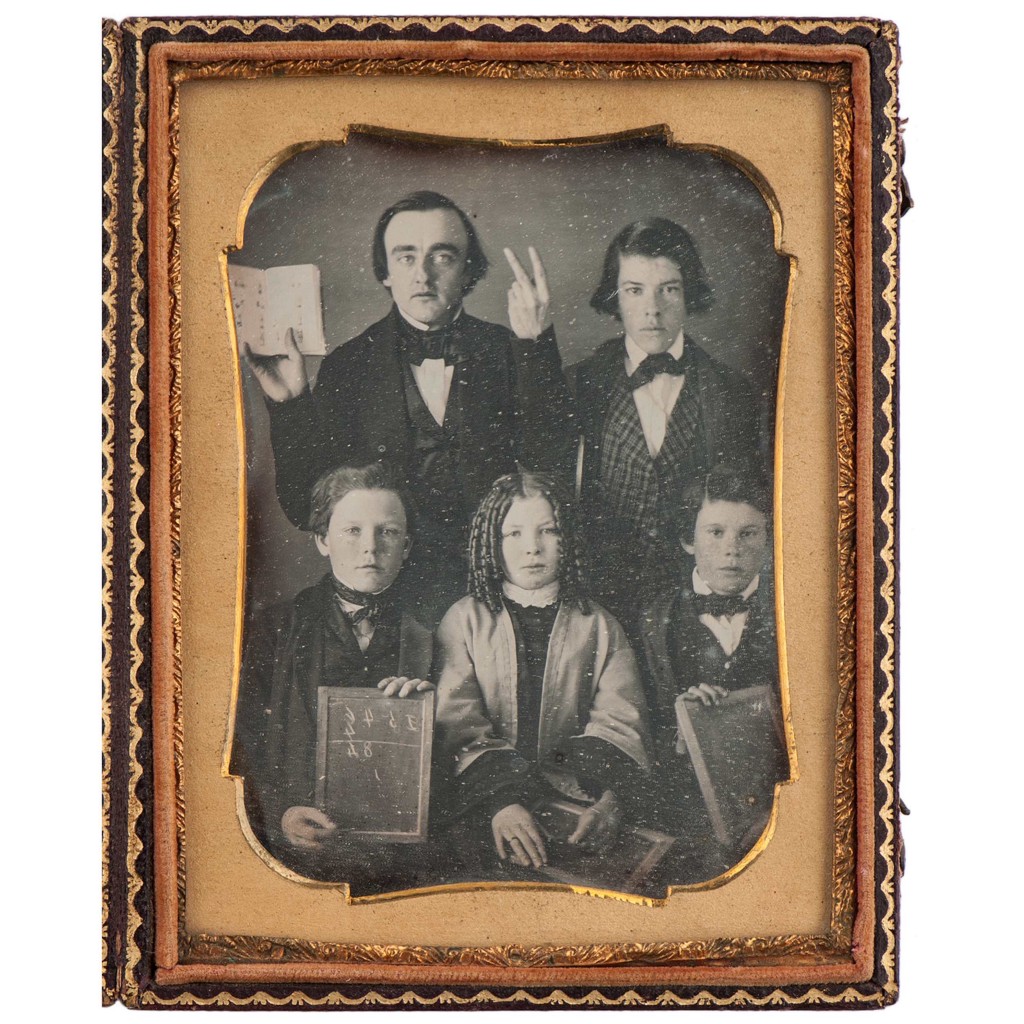

Lot 3: Ugh, Math

The Cincinnati auction house offering this c. 1853 daguerreotype of a schoolmaster on June 9 quite accurately describes it as “fabulous.” What’s really striking is that little more than a decade after Daguerre’s photographic process was presented to the public — when a person would be lucky to have one photo taken in their lifetime — this guy choose to spotlight his numerical proficiency by counting with his fingers (math before Common Core) and displaying his textbook. He is so sincere in his nerdery, one assumes that he must have been planning to use the wallet-sized image to advertise his tutoring services. His little scholars, with chalkboards in hand, play along, wondering when the hell lunch is.

The starting bid is $1,500.

Rebecca Rego Barry is the author of Rare Books Uncovered: True Stories of Fantastic Finds in Unlikely Places.

Rich People Ghost Town

“Luxury Blightscape” would be a good name for a band.

How they ruined Bleecker Street, and what’s going to ruin Bleecker Street next:

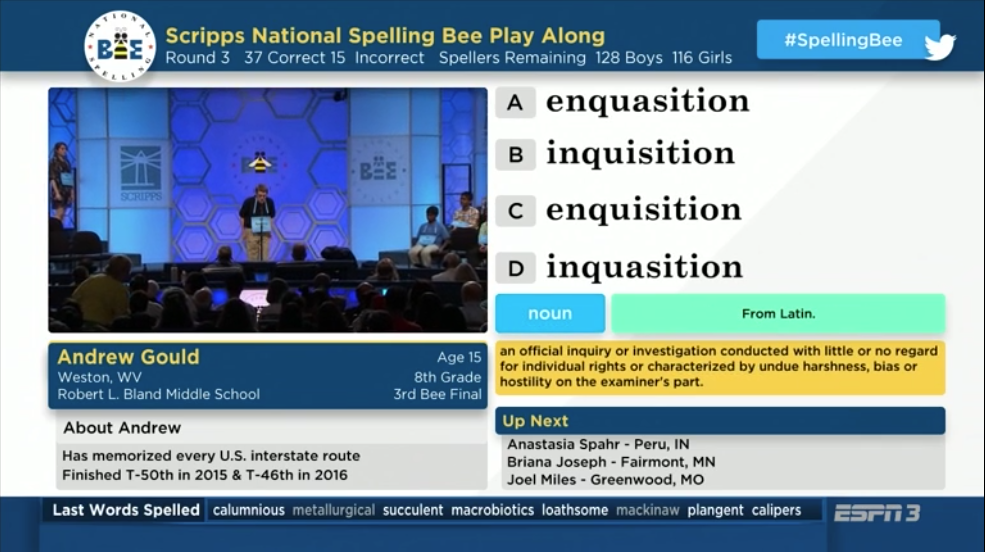

Everyone Turn On The Spelling Bee Prelims

It’s better than whatever else you’re doing (unless you’re outside in which case, carry on)

Are you smarter than a first-to-eighth grader? Trust me when I say no. Have you hit a bit of a late-afternoon slump? Open ESPN3 in one of your browsers and watch the kids spell! There are still, like, over two hundred of them left. You will know some of the words and other words will be insane. You can try the play-along version, which lets you guess alongside the contestants:

Or you can just tweet your guesses, which is much more fun than c*vf*f*.

jeep knee #spellingbee

Reiterate." "Can you please repeat the word?" "Reiterate." #spellingbee

Weedicide. Very different than we decide. #spellingbee

OH and there’s a very cute six-year-old named Edith in the competition!

This is what awesome looks like! #goedith #recordbreaker #itsoktobenervous #spellingbee https://t.co/9v97h4PBXP

If you have a subscription to Harper’s, run do not walk to catch up on this excellent story by Vauhini Vara, herself a former bee champ, about the surge in Indian-American competitors in the National Spelling Bee.

You can also read what one really beautiful genius wrote back in 2013 about the Scripps Bee; most of it is still true:

First of all, most of them haven’t yet learned how to hide what they’re thinking, much less how they feel, under nationally televised pressure. It is said of the best athletes that they make their skill look effortless, but in the spelling bee, there’s all kinds of trying on display. This year, the spellers range in age from eight to fourteen (they range in height from pint-size to near full-grown). Some of them approach their words with a certain amount of technique — they might ask for the language of origin or the part of speech, for etymological clues. Others fly by the seat of their pleated pants, relying on rote memory or phonological intuition. But one thing is constant: you can tell immediately from the look on her face when a contestant knows her word.

What are you waiting for? This is the best feel-good sports you’re gonna get all week, and it goes on all day, until tomorrow night on ESPN.

The Trump To Remember

Rebecca Solnit on fortune’s fool

If you haven’t read Rebecca Solnit in LitHub “on the corrosive privilege of the most mocked man in the world,” do so right now:

The American buffoon’s commands were disobeyed, his secrets leaked at such a rate his office resembled the fountains at Versailles or maybe just a sieve (this spring there was an extraordinary piece in the Washington Post with thirty anonymous sources), his agenda was undermined even by a minority party that was not supposed to have much in the way of power, the judiciary kept suspending his executive orders, and scandals erupted like boils and sores. Instead of the dictator of the little demimondes of beauty pageants, casinos, luxury condominiums, fake universities offering fake educations with real debt, fake reality tv in which he was master of the fake fate of others, an arbiter of all worth and meaning, he became fortune’s fool.

Rebecca Solnit: The Loneliness of Donald Trump

This is the one. It’s the one I will come back to over and over like that one Ask Polly, and I will read it again and again until it soothes me like Klonopin.

Floating Points, "Kelso Dunes"

What dumb thing happened today?

Listen, I’m not happy about it either. I’m not happy about any of it, but this is the world we live in now, and you’re just going to have to get used to it. Whatever it is today, tomorrow will be dumber and/or worse. This is where we are, and, as it turns out, this is who we are. I guess the only thing surprising about it is that we can still be surprised. I wonder how much longer that will last. Anyway, yes. You are not alone in your disgust. Yours are not the only pair of eyes that are sore from excessive rolling. That is not just you sighing audibly. This is How Things Are, and they might not ever get better. Listen to some music for a couple of minutes, that might take your mind off it. Enjoy.

New York City and Elmont, New York, May 29, 2017

★★★ Had the rain passed for good, and if not, when would it? Loose drops nicked the surface of the puddles. A car came down 72nd Street with a hiss of wet tires and a honk for the pedestrians waiting to step into the otherwise empty roadway. At midday, out in Queens, rain streaked the train windows and glistened on the highways. Drizzle was still falling on the Belmont Park platform, but sometime during the long walk to the paddock, that stopped too. Pale gray water still lay where the horses would take their walk around. Out on the sloppy track, the 14 horse broke out in front of the field and stayed clean all the way home, on a winning ticket. The five-year-old’s show pick came in right behind. His next show pick, on the wet turf, won going away. The puddles shrank and the benches dried. Safe bets kept paying off. The gloom and the wet had kept the holiday crowd sparse enough that the rail at the finish was usually open. Once, over the paddock, the shape of the sun appeared through a thinner part of a cloud before the heavy gray covered it again. The chill never faltered. More than half the field scratched in the fifth race, but the sixth, the last before the early train, was full of conceivable longshots—all of whom came home spattered in dun mud behind the five-year-old’s chalk-pick winner. The dark clouds over the homeward ride had more shine to them than the dulled steel of a passing train.

The Emperor Of Air

How a 19th-century French lawyer crowned himself a Patagonian king.

In 1895, an unfamiliar flag appeared above the rooftops of Mogador, today’s Essaouira, a port on the southern coast of Morocco. It was white and blue. In its center stood three mountains, crowned by a rising sun. One corner held an indigenous Chilean dressed in war paint; another, a guanaco (a kind of wild llama). A Liberty cap, stars, daggers and scales completed the eccentric design. It belonged to the Kingdom of Patagonia, whose consulate had just opened its doors.

At the time, Mogador was home to many consulates, and having a consulate was a necessary condition of doing business in Morocco. Consuls acted outside the scope of Moroccan law. They were exempt from taxes, and were able to extend this protection to as many people as they wished. This opened the door to many profitable abuses. Andorra, San Marino, Guatemala, Haiti and San Domingo, Siam and the Sandwich Islands, Kotei, Acheen, the Transvaal and Orange Free State all maintained representatives in the city. But Patagonia was something else entirely. Some Moroccans in town wondered whether Patagonia was a province of France. A few Jewish traders insisted that it was in Argentina, or in Chile and that it was not independent at all. They were right. But then, how to explain the presence of the consul, who went by the name of Abdul Kerim Bey, dressed in a fez and spoke a little Turkish and no Arabic, and who seemed to be in actuality an Austrian army Captain named Geyling?

I first read this story when I was teaching Moroccan history to a class of high school students in Tangier. It stayed with me ever since as a sudden, strange mirage. But it was only much later, reading Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia, that I learned the wider history behind it.

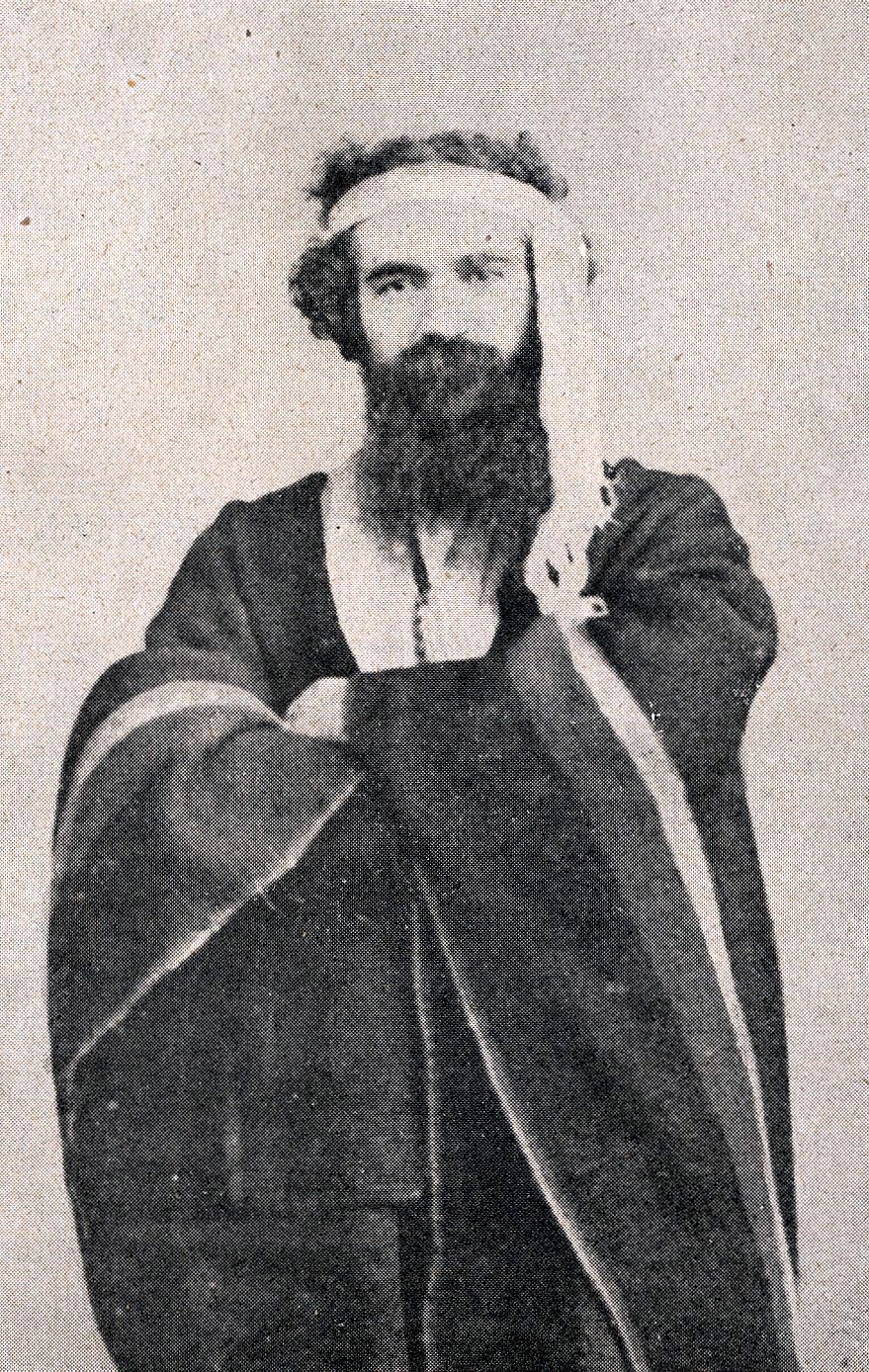

The truth was that the Kingdom of Araucania-Patagonia (its full name) did not exist, but it was not Geyling’s fantasy alone. Its story began some thirty-five years before, in the mind of a French lawyer named Orélie-Antoine de Tounens. Tounens was born in 1825. He was the eighth of nine children born to a prosperous farmer from Périgord. He believed his family was descended from Gallic nobility, and all his life, he wanted to better their station. From an early age he dreamed of restoring France’s fortunes in the New World. Napoleon and his nephew, Napoleon III, beckoned Tounens’s mind as examples of self-crowned kings. All he needed to do was to find a suitable kingdom. Reading Voltaire, he stumbled on the poems of a 16th century conquistador named Alonso de Ercilla. This settled his choice: he would go to Chile, and make himself king of Araucania.

Araucania’s name comes from its indigenous inhabitants, the Araucanians — known today as the Mapuche — a fiercely independent people who had maintained their independence from the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century all the way until the middle of the 19th. For all this time, the Bio-Bio River marked the frontier between slavery and freedom. North of it was the settled country of the Spanish settlers. South of it, all belonged to the Mapuche.

Ercilla was one of the conquistadors sent by Spain to Chile in the 1550s to subdue the Araucanians. Over decades of ferocious combat, Ercilla became awed by their indomitable courage. In the Araucana, his epic poem about the conflict, the Araucanians are heroes, equals to Hector and Achilles. Awed by their independence, he wrote “No king has ever ruled you/nor foreign power controlled you.” Still, as a servant of empire, he could not decide whether to depict the Spaniards as triumphant conquerors, like the Trojans from the Aeneid, or as villainous usurpers, like Caesar of the Pharsalia. He tells of one Araucanian chieftain who had his hands cut off as punishment for rebellion. He returned to his people, and used his bloody stumps as testimony to incite them to continued warfare. When his band was captured they refused to die by anyone’s hand but their own, and hanged themselves. Before this, the chieftain tells Ercilla that “We can be killed but not vanquished, nor can our free souls be enslaved.”

When Tounens arrived in Chile in 1858, the Mapuche were still unvanquished. Tounens waited two years before contacting them. In the interim, he studied Spanish and made contacts among the few French emigres who had already settled around Santiago and Valdivia. One of them, a farmer named Desfontaines, would become his staunchest ally and Secretary of State. In 1860, Tounens finally crossed the frontier between Chile and Mapuche country. He prepared the way for himself by making a gift of a piano to a Mapuche war chief named Mañil. According to a story recorded by the English writer A.R. Hope Moncrieff, when the chief received his gift, he had the hammers and strings removed from its insides and turned the piano into a bed for himself and his wife.

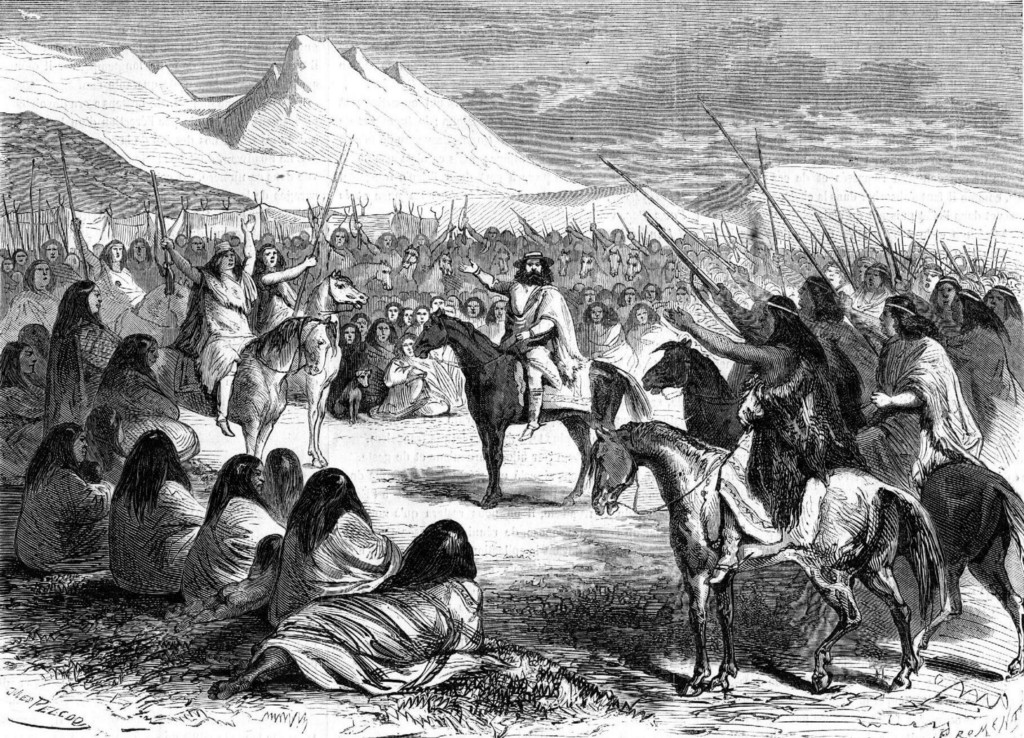

By the time Tounens arrived south of the Bio-Bio River, Mañil was already dead. But his successor, Quilapan, was equally interested in resuming war with the encroaching Chileans. Tounens seized his moment. Dressed in a royal costume he had made for himself out of a finely woven black-and-white poncho, silver belt buckle and spurs and long sword in a sheath inlaid with gold, he met with the Araucanian chiefs during one of their assemblies. Through an interpreter, he promised them weapons and ships with which to fight the Chileans, though he had neither.

In the following days he watched as they conducted a trial entirely on horseback; he envisioned a parliament conducted in the same manner. From the farm house of his friend Desfontaines, he proclaimed a constitutional monarchy with himself at its head. He drafted the constitution himself. It granted universal suffrage, individual liberty, legal equality and established proportional taxation. The monarchy, though, was reserved to Tounens — now King Orélie-Antoine I — and his family. In the event of his death, the crown would pass first to his father, then to his eldest brother, then on to his brother’s son. If all these should perish, it would go to “our well-beloved niece, Lida Jeanne de Tounens and her descendants in perpetuity.”

This remarkable document, encompassed in nine chapters and sixty articles, was ratified by an assembly of Mapuche chiefs. Possibly, they simply had a —King Orélie’s relationship with his subjects was dogged from the start by mutual incomprehension — but in any case, Tounens was convinced he was a king — a duly elected king, much like Napoleon III, or Euron Greyjoy. Soon, an emissary arrived from across the mountains; the Patagonian tribes were also interested in joining his kingdom (or asserting their independence). Tounens immediately annexed them to his realm and rushed to Valparaiso to let the world know about his deed.

The Chilean government ignored him. In 1862, he returned to Araucania from the settled part of Chile. The Mapuche were gathering for war. He rode with their army for the frontier. Finally, the Chileans took alarm, and made inquiries. While making his way back south across the frontier, Tounens’ interpreters betrayed him. Chilean soliders apprehended him in the act of taking a nap under a pear tree. Nine terrible months of imprisonment in the provincial capital of Los Angeles followed, during which he lost his magnificent black mane. Released, possibly thanks to pressure from the French consul, he made his way back to France.

He tried three more times to re-enter his kingdom. On the first attempt, in 1869, his arrival was treated as a miracle, since the chiefs had been told by he was dead. Soon though, the Chileans put a price on his head as a fomenter of rebellion, and, running out of money, he was forced to flee back to France. The second time, in 1874, he went in disguise, but was discovered and arrested. On the last attempt, in 1877, he contracted a terrible case of dysentery, which nearly killed him, and required that he be fitted with a silver anus. The following year, he was back home in his brother’s village of Tourtoirac, working as a lamplighter. By the end of 1878 he was gone, having died penniless in a Bordeaux hospital.

Questions remain: how did Dr. Abdul Kerim Bay/Geyling come into his consulship? According to the Scottish adventurer Robert Cunningham Graham, who met Kerim during his stay in Mogador, thought he might have been one of King Orélie’s hangers-on from his time in exile in France and Argentina. More likely, Kerim simply assumed that no one would question the existence of the Araucanian state in a place that was at once as cosmopolitan, and as cut off from the rest of the world, as Mogador. Indeed, the consulship was a front for more than just taking bribes. It turned out Geyling was involved in a scheme to sell guns to the tribes of Morocco’s south, and the consulship was his cover. But before the sale (strictly illegal under Moroccan law) could be concluded, Geyling absconded back to Austria, leaving his partner, one Major Spilsbury, stranded in a yacht off the coast with a cargo of repeating rifles.

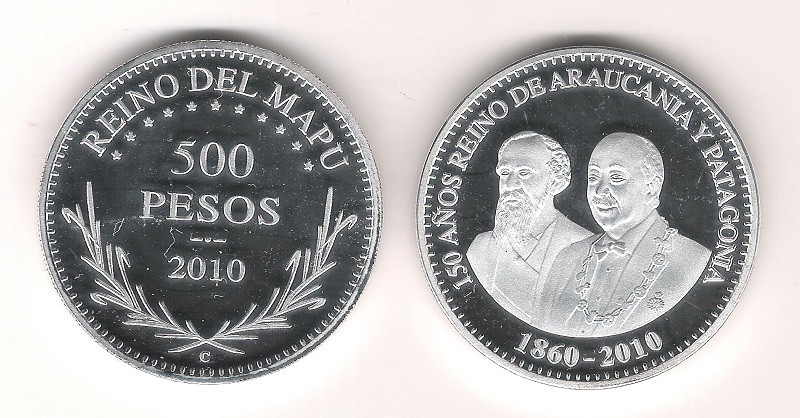

Meanwhile, in Périgord, the Patagonian crown passed from hand to hand according to rules set down by its founder. Seven kings and one queen have by now had a turn on the imaginary throne. Quite a dynasty, even if it is electoral. Their exploits are detailed in issues of the official Araucanian newspaper, The Steel Crown, their faces shine on the medals issued by their Royal Mint. But that isn’t to stay the succession always proceeds without a hitch. Last year, the throne passed to Jean-Michel Parasiliti di Para of Paris, a 73-year-old confidant of the former king. His opponents rallied to the cause of a rival, a 20-year-old named Stanislas Parvulesco, who was immediately denounced as a renegade. In the pages of the (French-based, but also digital) Araucanian press, the quarrel has grown bitter. Neither claimant seems ready to back down.

In between his voyages to and from France, King Orélie published his memoirs, bestowed titles, founded a newspaper La Corona de Acero (“The Steel Crown”), and searched for a bride. While in France in the 1870s, he was approached by another visionary: Eugène Pertuiset, big game hunter, inventor of exploding bullets, and subject of a portrait by Manet. Pertuiset offered to give him some valuable intelligence. He claimed to know the location of an immense treasure buried by the Inca in Tierra Del Fuego, which he had learned it with the help of a medium or seer. The proposition was tantalizing, but Orélie dismissed him. He was a king, and had no time for idle dreamers.