Building History from Cinematic Trash

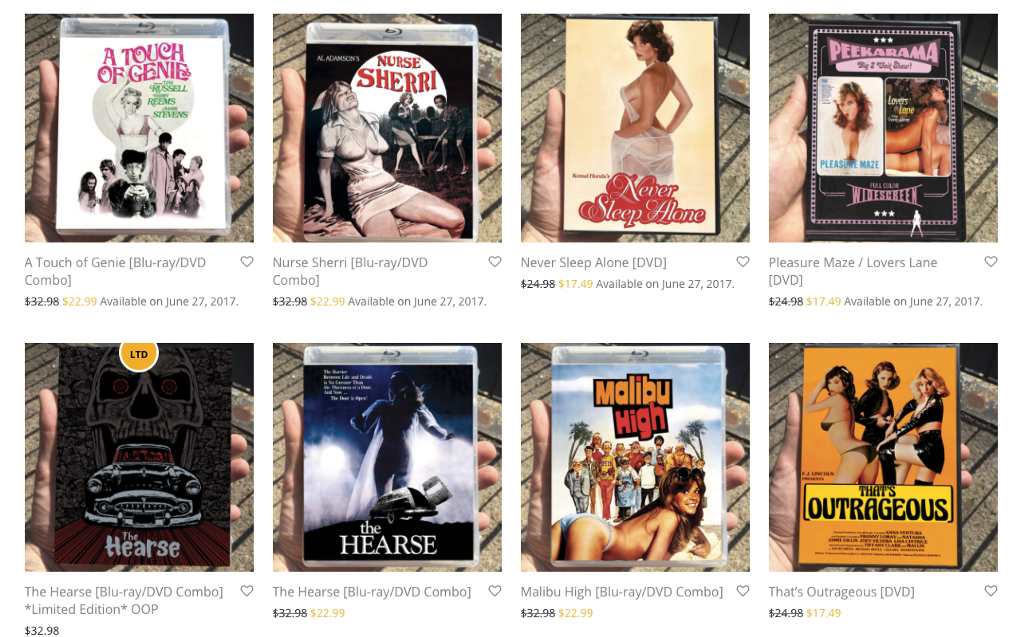

At The Vinegar Syndrome

Brandon Upson spends his days watching some of the world’s most obscure schlocky films. As a devotee of the low-rent and sensationalist exploitation film genre, he’d probably do so regardless of circumstances. But it’s also his job. Upson is currently the lead film restorer for the Vinegar Syndrome, a tiny company that has over the past five years amassed crates upon crates of rare, forgotten, and often literally crumbling low-end b-movies in a nondescript office in Bridgeport, Connecticut, with the aim of preserving them all, and distributing some to a wider audience.

This might seem like a meaningless pursuit. Some of these flicks were forgotten, explained Upson, in part because their makers thought they were pure crap. “A lot of them say, ‘you mean you’re actually interested in this?’” he recalled of a common refrain from incredulous rights owners he has reached out to. To an extent, the Vinegar Syndrome team does seem to run on pure fanboy zeal. But the team’s work is universally beneficial. Many exploitation flicks have more to offer than just the blood and boobs they used to sell tickets back in the day. Some are actually trenchant social commentary; all are historical items that speak to the values and conversations of often ignored social spaces. It’s hard to probe the true depths and impact of these films without a robust historical archive.

Unfortunately, explained Upson, most of these films were produced before film archiving and preservation started to take off, initially in the ’70s but only with vigor in the late ’80s. To this day, not many preservationists want to touch exploitation films, deeming them too low-value or controversial; even academia didn’t cop on to the messaging and unique delivery potential of the genre in any meaningful way until the late 90s. Some old copies were left to rot in warm, damp spaces — literally rot in a process of decay that lent Vinegar Syndrome its name. Others, lamented Upson, “they’d throw in dumpsters or — and this really happened — throw them into the ocean. Literally, they’d just throw them into a dump truck [toss them off a ledge] and drown them.”

Exploitation film is, at its definitional core, a cutthroat pursuit of uber-capitalists, churning out cheap movies quickly to exploit some zeitgeisty trend or controversy. It developed as early as the 1920s, but reached its zenith from the late ’60s to the early ’80s, an era of loosening censorship and declining theatre attendance. Reveling in the freedom to pursue and keen to the marketability of mankind’s most prurient interests, genre filmmakers create a slew of newly minted subgenres, like blacksploitation (think 1975’s Dolemite in which local cops get a black pimp, played by a comedian, out of jail to take down a local gangster with his band of martial arts-proficient prostitutes), Nazisploitation (think 1977’s Last Orgy of the Third Reich, an hour and a half of hardcore sadism and what is essentially rape porn set in a death camp), and rape and revenge fantasies (think 1972’s The Last House on the Left, in which psychos abduct two teenage girls, brutally raping and murdering them, then are in turn brutally killed by the girls’ family members who learn of their fate). But they almost all indulged heavily in egregious sex and violence.

Quite a few of the resultant pictures had little to no redeeming value, like 1975’s Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS, which used Nazi concentration camps as a backdrop for unforgivable sadism and soft-core pornography. (That film, developed oddly enough in part by Ivan Reitman of Ghostbusters fame, actually spawned several ever more inane and grueling sequels.) However, many leveraged their expendability into social commentary. “Producers would probably say something like, ‘it’s got to have a kill scene, it’s got to have a sex scene… and I need it by this day and you have this budget,’” explained Upson, “‘otherwise do whatever you want with the story.’ And that’s when you would have these directors or writers doing politically motivated things with it as well.” To wit, Dolemite, for all its absurdity, made some salient comments about institutional racism. Even the nearly unwatchably gratuitous The Last House on the Left, which was actually the directorial debut of the recently deceased horror film icon Wes Craven, was actually (Craven admitted towards the end of his life), twisted meta commentary on the abstraction of violence in the Vietnam War era, forcing people looking for the cheap thrills of a murder-and-rape flick to confront what Craven saw as the true brutality and viscerality of human violence.

Genre film in general has often discreetly carried social commentary, hiding radical or controversial ideas under the veneer of a common and digestible narrative framework or set of expected audience gratifiers. High Noon brought anti-McCarthyism to audiences at the height of the Red Scare in 1952 via Western tropes, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (both the 1956 and 1978 iterations) followed an established sci-fi trend of commenting on Cold War paranoia, and Night of the Living Dead put horror into dialogue with anti-Vietnam War rhetoric in 1968. But exploitation had special abilities — namely, its moral abandon and embrace of exaggeration and depravity. It allowed creatives to dig deeper for starker gut punches or more direct and at times alienating critiques than mainstream film could offer up to mass and more reserved audiences: On the gut punch side, for example, John Waters’ 1972 Pink Flamingos far beyond any rational boundary of transgressive humor as weirdoes duke it out for the title of world’s grossest person. And on the withering, tangible social critique side, 1982’s Slumber Party Massacre gives a psychopathic man a drill — a starkly obvious symbol of toxic machismo — and lets him express the horrors of that mindset on a house full of young girls before he meets his just fate.

Even at the time, these films had the power to spark dialogue, both in the Grindhouse theatre space and beyond. They also slowly reshaped mainstream film, birthing accepted genres from slasher horror films like 2005’s blood-soaked Hostel, itself director Eli Roth’s overplayed attempt at punishing bro-y American ignorance via torture porn, to sexy-drenched teenage romp comedies like 1999’s American Pie and its spiraling, dumb franchise, not to mention inspiring the “mockbuster” craze that bedevils so many hopeful Netflix users these days. But these days, old exploitation joints can take on a new light; their immediate titillating qualities may have eroded due to changes in social obsessions and developments in filmmaking techniques, but their messages and other stylistic and artistic merits remain. This has allowed some, like 1932’s carnival sideshow-starring horror film Freaks, to be redefined as works of art or classics. Even those that didn’t get canonized wound up serving as crisp memories of how ideas were once framed, and sometimes-potent reorientations of those ideas for those who aren’t familiar with their histories or vintage; even at their silliest, blacksploitation films especially speak to a degree, intentionally or incidnetally, about race as seen through the eyes of more diverse and creatively free crews and casts than Hollywood could offer up in the ’70s. “It’s almost like an archaeological dig, where you see these new ideas that are actually 30 years old” put on unexpected display, says Upson.

As Upson has learned, there was no guarantee that the exploitation films that survived would be the most valuable, influential, or widely known. The end result being a highly fractured and fractional archive. (“Exploitation film from the ’70s to at least the early ’90s,” argued Upson, “other than silent films, [is the] genre [that] has the most lost films.”) What archive did exist was long functionally scattered amongst small, fiercely independent collectors as well. That’s a problem for anyone trying to build a cogent story about the true contours and full scope and impact of the exploitation genre as a serious piece of socio-cultural history. You can build narrative, draw meaningful insight, from a robust and central archive. A scattering of items just presents interesting case studies and suggests a story; it offers the ability to wax poetic about a medium’s potential and build hypotheses on its value and impact, but nothing more.

That’s where the obsessive fanboys at Vinegar Syndrome come in. From the very beginning, they focused on tracking down lost and forgotten exploitation films and saving them from decay via digital restorations and back-ups. While they make some cash by re-releasing films (and they’ve far exceeded their expectations on how many they’d put out, with dozens upon dozens on offer through their company store), Upson says they’ll preserve anything regardless of its distribution value. They’ve acquired thousands of exploitation films, as well as old industrial and educational reels. Their devotion to the genre, talent as archivists, and success at scouting and acquainting other aficionados with hidden jewels has earned them a high degree of respect in the exploitation collector community and also substantial visibility beyond that insular world. “People are coming to us now and saying, ‘I know you’re looking for films and I think I have [something] that’d be good for you,’” explained Upson.

At least according to Upson, the Vinegar Syndrome team isn’t that interested in using the uniquely complete and concentrated archive they’re creating for their own academic dissection. Upson says he’s learned a lot about the motivations of filmmakers by reaching out to rights owners; he’s been especially surprised by how many didn’t even recognize the artistry or social commentary someone on their crew had slipped into their works. Any insights that come out of their joyful packrat ways is an appreciated bonus, but incidental, though.

Even if they are not academics, they are still potent distributors. The team has collaborated with film programmers at festivals and theatres across the country to put some of their finds back on the silver screen. They also successfully crowd-funded exploitation.tv, a Netflix equivalent subscription service putting high-resolution streaming copies of hundreds of items from their catalogue (and growing) at the fingertips of anyone in the world. Naturally, the Vinegar Syndrome team’s work serves existing genre fans above all others. But it also offers researchers easy access to a new and potent historical resource and promotes the visibility of the genre to academics and amateur historians who might never have thought to dip their toes into it before.

“The fact that people really seem to like [the films we find] and are interested more and more in [the exploitation genre and] what we’re putting out is awesome and it helps,” said Upson. But for all his nonchalance about the exposure and impact his work has achieved of late, this may be the coolest thing about this strange labor of love. It’s passionate archival work by another name. It’s creating the access and outreach modern society needs to better understand and draw upon the historic and still potent value of the exploitation genre. Whether at its obsessive archivists’ hands or not, the Vinegar Syndrome collection will leave a mark. One hopes it’s as senselessly bold, raw, and ultimately cosmically meaningful as the mark left by the exploitation genre itself.

Is Germany Blowing It?

Deutschland über us.

“BOOM + ELECTION = BUBBLE,” proclaims University of Dortmund economics and journalism professor Henrik Müller in a provocative op-ed in Der Spiegel this week.

Go ahead, dude, rub it in: The German economy, thanks to either its people’s inherent genius or their indiscriminate Europe-wrecking penny-pinching, is allegedly booming — or, to use the German, it boomt. “Employment, state revenue, exports, corporate morale — all at record highs,” Müller explains. “Real estate prices are rising rapidly, both in large cities and rural areas. The construction sector is expanding.” GREAT.

But wait! Economists, “largely in agreement,” warn that German companies have been working beyond their production capacities for some time, and that the economy is, and will remain, überhitzt (OO-bur-HITST), or “overheated.” Yes, Müller allows, this boom could last for years. “But that doesn’t make it any less dangerous,” he warns. “For the longer the boom, the harder the bust.” Unless someone (possibly someone in a brightly colored pantsuit?) does something, the German economy is headed for a bubble.

The same mechanics are always at work: In times of pronounced boom, economies get warped. Over-optimistic expectations provoke investments that later prove to be unsustainable in the long term. Overvalued financial and real estate markets make citizens and businesses blind to risks — which comes back to haunt them when values plummet. Then comes the crash.

The problem, says Müller, is that Germany’s in an election year, and apparently nobody’s eager to campaign on the platform WE MUST STOP THIS IMPRACTICAL BOOM — even though, from at least this outsider’s perspective, that would be the single Germanest campaign slogan in the history of Menschheit.

Müller’s is your standard-issue mildly interesting Krugmanian/Keynesian boilerplate, just in BUSINESS GERMAN, so automatically more authoritative-sounding. But its interest is compounded for American observers (GET IT? MONEY JOKE!) when we consider the multitudinous cross-cultural delights that lurk inside.

First, the German word for “election” is der Wahlkampf (VAHL-komff), which literally means “vote fight,” and who doesn’t enjoy the mental picture of she who so recently jilted us in the boxing ring, kicking the asses of a bunch of balding dudes in tiny glasses? I bet she’d have a special boxing suit jacket made, or perhaps one in every color, and they’d all look amazing.

Second, the German word for “bubble,” as you can see in the Spiegel headline, is die Blase (BLAH-suh), which, coincidentally, is the same as the word for “bladder,” which for anyone who has ever read Little House in the Big Woods, makes perfect sense.

But Blase is also the nominalization of the verb blasen, which means “to blow,” which, as in English, carries meanings in both the bubble-based and fellatial sense. To say blow me in German, for example, you say Blas’ mir einen, which literally means blow me one, BUT — as my flatmate Henrik was clear to point out when I asked him for this very translation in 1997 — is not to be used as an insult, but simply a request.

Speaking of which: Müller suggests that the only way to avoid the bubble is to do the economic equivalent of stopping mid-hookup to inquire about your paramour’s most recent HIV test and the whereabouts of his or her prophylactics. And, even though it’s the 90s and everybody cool does it, that conversation is a 100-percent boner killer, with “boner” here being Business German for “elections.” (Let it not be said that I don’t put the ‘shaft’ in Wirtschaft.)

Anyway, according to Müller, who I am sure definitely supports this extended sex metaphor (and I’m just getting started), the German-economy-saving equivalent of Where the Gummis at? is to raise federal interests rates in the name of gegensteuern (GAY-gun stoy-urn), which technically means “countersteering,” but also carries within it the word for “to tax,” steuern—which also means “to steer,” “to pilot,” “to govern” and “to regulate,” which is where the second part of Müller’s boner-ruining plan comes in.

For, he argues, another crucial way to prevent a bubble is — Paul Ryan, you might want to look away — to steer the German economy in the right direction by curbing demand, by raising individual income taxes on the middle class specifically. WUT? IS THAT EVEN LEGAL TO WRITE? “You read me right,” he assures me. “To only increase taxes on the wealthy (as the Left demands) would bring little stability, because these additional burdens would hardly slow down high earners’ lust for consumption.”

Wait, so taxing the bejeezus out of the rich doesn’t stop them from buying shit? But that’s not even his point. His point is that they have to get ordinary Germans to stop buying so much shit. But this suggestion is the electoral equivalent of not just asking where the rubbers is, but of explaining in detail the symptoms of advanced gonorrhea. Or, in the Business German: “Politically, this idea is not feasible.”

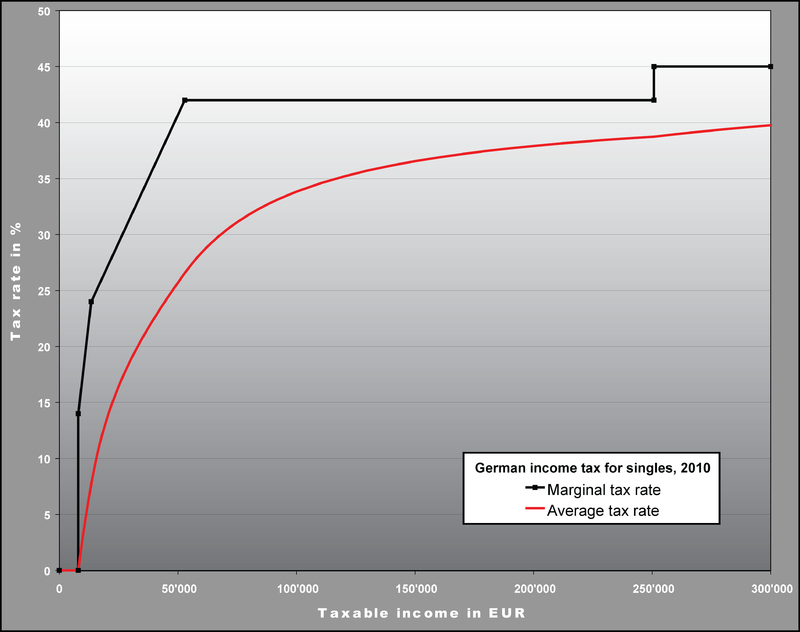

Some perspective: Current German income tax rates range from zero to 45 percent of one’s taxable income, with a “middle-class” earner of about 50,000 Euros per year taxed at what Americans would see as an extortionate 42 percent. (Although, because university is free, it just might end up balancing itself out, considering.) German goods also include VAT in all prices (be prepared for an earful if you ask about the American practice of adding on sales tax at the register), and Germans pay a set 8 percent of their pre-tax salary toward the Krankenkasse, or national health insurance Koffer.

So on the one hand, you can see why anyone who wants to win an election isn’t campaigning on a promise to raise those rates even higher. “It’s logical,” agrees Müller, “that nobody wants to be the buzzkill — the person who turns the music down and the lights up.”

On the other hand, you’d think that if there was one thing Germans would be great at, it would be ruining a party.

There’s no quicker and more efficient way to “put the brakes,” as Müller says, on a great time than to tell a joke to a German that involves any measure of sarcasm or exaggeration — you can almost hear the record-scratching sound, as all merriment halts in the afterglow of the universal German anti-mating call of Ektually, zet’s not right.

Also, honestly, if you’re already paying 42 percent of your income toward your country’s staggering array of immaculate free parks, roads, bridges, schools, universities, doctors, spa cures and day cares, and you do so out of a completely different understanding of what it means to be in a free society, what’s another few hundred Euros to insure against den Crash? I mean, Germans insure everything else on God’s green earth, why not their economy?

It appears to me, a seasoned economist if ever there were one, that the major German political parties’ resistance to running on a very Teutonic cautious boom-dampening may be a result of GLOBALISM RUN AMOK!!! If the Paris climate agreement, a.k.a. The One-World Government of Gun Taking and the Antichrist masquerading as “people who understand scientific fact,” can infect America despite our brave President’s ability to see the TRUTH, what’s to stop globalism from operating in reverse? The Information Superhighway runs both ways, after all: If the Elitist Cosmopolitan Polyglots can infect us with their bogus “climate stuff,” clearly we can also infect them with our ridiculous belief that unfettered Capitalism is virtuous.

Yes, Germany may think it’s broken up with us, but not before the metaphorical mutual Blasen of our years as super close allies left a little something in its wake: It appears the worst aspect of American influence has lingered in Germany, like if Ayn Rand were an STD.

As Müller suggests, if the politicians don’t start counter-steering the ship, Germany may have already blown it. (Or, at any rate, it comforts me to think so, and have a little Schadenfreude in my continued time of heartbreak.)

Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith, "By Your Side"

It’s confusing these days.

Remember when you had a pretty good approximation of what day it was? I’m not talking about the occasional, “Ugh, I thought it was Friday but it’s really Thursday” mistake. I mean, if someone asked you first thing in the morning when you woke up to name the day, you would for the most part be able to answer correctly, because time moved in a linear fashion and everything progressed in a regular way. Now who the hell knows, and what difference does it make either? For the record, today is Wednesday, but again, what does that even mean anymore? Anyway, here’s synth wizard Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith doing a Sade cover. Enjoy! [Via]

New York City, June 5, 2017

★★ The air indoors had been so thick and stuffy that the chill of outdoors felt pleasant for a minute or two. The dampness soaked in everywhere: The downtown 1 train car was cool with air conditioning but still damp; the R train, unmoving in the station, was warm and damp; the Q that finally arrived on the express side was cold and damp. Up on the surface, the wan sun through the clouds grew a tiny bit less wan for a moment and the thin shadows thickened a little, but only a little. The thwarted late light of the long day manifested itself only as a faintly warmer glow over rush hour, coming from nowhere in particular. A fog was up in the top of the landmark skyscrapers but below it was a weaker sickly sort of partial fog, slightly occluding everything.

One Of The Best Things About The New "Twin Peaks" Is The Musical Cameos

At the end of every* episode

Remember when bands would play songs on TV shows like “The O.C.” or “Gossip Girl” and it would be, like, loosely written into the plot, like at a nightclub or a prom, and it was a big deal for both us and also them? Everybody won in that situation: you get to enjoy a cool new song, the band got exposure, and the creator of the show looked smart and good even if it was the music editor’s choice or even suggestion and the music editor’s second assistant who actually managed the booking. Remember?

The second coming of “Twin Peaks” has been doing the same thing in the past four episodes, loosely set at The Roadhouse, and it has been great. Thank you to David Lynch. Or David Lynch’s music person’s second assistant.

Your Guide to All of the Bands in Twin Peaks

Vulture will be collecting them all in one place here, which is less fun that Googling “what was the song at the end of twin peaks episode 7,” but much more efficient.

*except the first one, I know I know.

Destination Reading

It’s almost as good as couch reading

When the weather’s bad it’s easy to justify doing next to nothing all weekend long. If it’s cold out and especially if it’s raining, who really wants to go to a bar or to a museum? Sure bars and museums are heated and dry, but you still have to travel. No one can blame you for watching television or reading for, say, ten or twelve hours. No one; not even yourself.

Good weather makes it much harder to laze. It’s challenging — it takes a special kind of will-power — to look out the window, notice people walking around in shorts, and say to yourself, “Nah, I’ll just sit on the couch.” Pressure to act is everywhere: Each list of great new outdoor restaurants, each ray of natural light that obscures your screen. Sunshine is very judgmental.

Eventually, you break down and accept that you have to leave the house; you just can’t handle the guilt. But there’s a way around true activity and/or socializing. It’s called Destination Reading. Destination Reading just means you pick a destination and read there — read a book, a magazine, Twitter. Whatever. But everyone loves a label, and labels confer dignity.

There’s an art to Destination Reading; some are better at it than others. Only rubes would pick a truly nice location, like the beach. If your surroundings are too spectacular they’ll distract you from your page or screen and you’ll find yourself admiring nature or maybe even hiking around in it. But you don’t want to pick somewhere uncomfortable, either. Let’s face it: If you find yourself at a crowded cafe with rickety metal chairs, you’ll get tired of it quickly and go back to your couch.

The trick is to choose a place that, in the manner of Goldilocks, is just right, a place that’s neither special nor objectionable. You’ll know you’ve got it if your friends, when they hear that you’re heading there, say, “Oh yeah, I’ve been once or twice.” They’re not super eager to return, you see.

In Los Angeles, where I live, the best Destination Reading spot I know of is in the Descanso Gardens, a 150-acre park with a rosarium, a Japanese tea house, an odd little enchanted railroad for children, and a whole lot of oak trees. Haven’t heard of it? I’m not surprised. It’s not nearly as famous, or beautiful, as the Huntington Gardens in nearby Pasadena. But if you head into the area they call the Oak Woodland and follow the trail uphill, you’ll soon find a bench with a pleasant but uninspiring view, positioned so you can’t see other visitors until they’re about ten feet away. You can get a lot of reading done there and still feel like you’ve “done something” with a summer afternoon.

In New York, where I used to live, I’d recommend the Pratt campus in Clinton Hill, home to the Pratt Sculpture Park. The sculptures there are OK, I guess — I know nothing about sculpture. Anyway they never took up too much of my attention. I’d just stroll by the guards, find some dry grass under a tree and open my book. Probably everyone assumed I was an oldish student or a youngish professor. At the end of the day if anyone asked what I’d been up to, I’d have nothing to hide. Who me? I did some Destination Reading at the Pratt Sculpture Park.

I can’t say Destination Reading beats Couch Reading, but it’s a pretty good alternative.

Juliet Lapidos is an editor and writer.

How The Media Mishandled The Ghost Ship Fire

The ghoulish motive of being the first to document grief.

A few minutes after 11 p.m. on a Friday night in December 2016, a fire started in the Oakland warehouse known as Ghost Ship. That evening, the live/work artist space had been hosting a benefit concert for an L.A.-based record label that specializes in house music. By midnight, the space was destroyed, and thirty-six people were killed.

When word began to spread about the rising death toll — it was the deadliest fire in Oakland history, the most deaths since 2003’s fire at the Great White concert in Rhode Island — media outlets shipped reporters in to cover the tragedy. The networks sent weighty cameras and big budgets, the cable news channels sent proxies to provide a live lead-in to their split-screen shouting matches between four or five suited pundits nestled in comfortable studio digs around the country, and the East Coast publications of gravitas packed their pens and handheld tape recorders.

By the next night, they’d all arrived, a massive influx of reporters infiltrating the relatively small community. They were on the hunt, roaming for quotes and digging for narratives, to find any loose scrap — accurate or otherwise, beneficial or not — to feed their 24-hours news content monster. This isn’t a critique of media or journalism, which, when given proper resources and time necessary to follow ongoing narratives and understand the world in which they take place, does important work that benefits society. The issue in Oakland, in the weeks after Ghost Ship, was spectacle media’s piranha-like swarm on the city: moments of confusing, bubbling chaos, and a pile of bones left behind.

The mainstream media began overstepping their boundaries when an editable-by-anyone Google Doc appeared online. It was created in the hours after the fire, when information as to who was at the event, who was in the hospital, who’d perished, and who’d gotten to safety was still murky. Friends and loved ones clicked the link — passed freely far and wide, without censorship — in the hopes that, when the doc loaded, whoever they knew would be marked “safe.” “This was how we found out about our friends dying, as people were confirmed and not confirmed,” said Jonah Strauss, a music producer and engineer whose own live/workspace was lost in another Oakland fire in 2015.

The sheet also included phone numbers to close contacts of the missing, and with it spreading across an expanding network online, the media was inadvertently handed a trove of private information. Trolls eventually got a hold of the document, and did what they do, posting false information in between ethnic slurs. But before it closed, members of the media felt they should confirm the information on the doc first-hand, and so began cold-calls to the numbers, to confirm whether or not the person named was, in fact, dead.

“[The Google doc] was a great repository for loved ones to find out the right information, but then it was used against them by media outlets contacting them,” said Dustin Caruso, a native Oaklander long embedded in the music scene. “In times of tragedy like this, it’s one of the few times where you go talk to the authorities, get the information, and then if you need to, do investigative journalism later. You don’t talk to grieving families when the wounds are still fresh.”

While verifying information is at the core of journalism, in this instance, the process led to them becoming part of the story they were covering, kicking up silt in the already-clouded waters for no real benefit. No one was in any potential immediate danger that’d necessitate confirming those missing in the fire right then; the only thing at risk for waiting a day or two for official confirmation was the loss of a scoop. The only possible motives to justify these calls, then, are either for the ratings that come with being “first,” or documentation of grief in its most pure form. Both motives are utterly ghoulish.

These missteps followed on Monday night, at the candlelight vigil for the deceased at Oakland’s Lake Merritt. By then, the names of the dead had been established, so this moment, in the media’s mindset, was not about investigation or prying, but simply about capturing on an emotional event live. “All of a sudden, some camera gets shoved in our faces,” said Kit Friday, an Oakland writer who lost friends in the fire. “They’re like, ‘oh, hi, it seems like you lost someone. Do you want to talk about it?’ Fuck you. Fuck you so hard. Have we been stripped of our humanity to this level that you’re going to shove a fucking camera in someone’s face who’s clearly mourning?”

“I saw the kinds of cameras they had. You can be a few yards away and still cover it. You don’t have to be in the thick of it with your lights in everyone’s faces,” said Caruso. “There were a few people I wanted to run into, just to give them a hug and see how they’re doing. But within five minutes, I had three different reporters coming up to ask if I wanted to talk. I just ended up leaving after about an hour.”

A microphone had been set up, ostensibly to provide those grieving with a chance to honor lost loved ones, a goal quickly co-opted, perhaps accidentally, by politicians (mayor Libby Schaaf’s speech was met with raucous boos), and random members of “the scene” who felt emboldened enough to address the crowd despite, as noted in their remarks, not personally knowing anyone in the fire. One wonders if these speakers were actually addressing the crowd, or the cameras swarming within. The event’s aesthetics were such an enticing visual from above — thousands holding candles on a clear night at the lake — that most spiels were drowned out by the twirling blades of the news choppers hovering above.

After the vigil, it was clear any memorials should be held privately, away from prying eyes. But the media soon found a social opening they could exploit: Bars.

“There were reporters hanging in the Telegraph Beer Garden, trying to edge into conversations,” said Strauss. “It was really fucked up. Any place where people would hang out, they would somehow find out.”

“It felt like you couldn’t go to a lot of places without being inundated with coverage,” said Caruso.

“I went to Eli’s Mile High Club, and there was a just a swarm of cameras outside,” said Friday. “The term ‘vulture’ gets thrown out a lot, but this was truly… it was just a feast for them.”

Eli’s soon became a safe space. Under instructions by owner Billy Joe Agan, the bar instituted a media blackout; any journalists discovered to be working inside its candle-lit confines would be moved out onto the darkness of Martin Luther King Blvd. Media members still stalked outside for quotes, but past the bouncer at Eli’s, the atmosphere was free from outsider interference.

“Eli’s was a makeshift crisis center,” said Caruso. “I can’t put into words how important that was. Going to Eli’s was the place where people who were directly affected could converse with each other, get the right information, and also grieve together.”

“We needed that safe space, where we could cry and think ‘maybe they’re still in the hospital,’” says Friday. “We could experience that without being somebody’s reality TV show.”

Soon enough, the narrative of the fire was shifting, away from the loss of thirty-six lives and the safety failures of the Ghost Ship, to this being the logical result of an unchecked “rave” culture. “These partiers chose to have a rave,” was the sentiment. “They deserved what was coming to them by not taking the proper safety precautions.” This led to those many righteous stories from talking heads, grandstanding about a culture they know little about. (Very much related: NBC’s “Chicago Fire” dramatized the tragedy in a February episode entitled “Deathtrap.”)

Eventually, the national media, as it does, went home. They had other stories to cover, beginning with the fallout from the inauguration of Donald Trump. Local media, meanwhile, continued pounding the pavement and hitting up sources, to pretty accurate and worthwhile results; East Bay Express and KQED public radio offered compelling portraits of the deceased, while The East Bay Times won a Pulitzer Prize for their extended coverage.

But the fallout from the mainstream media’s portrait of Ghost Ship persists even now, six months later, with the continuing dismantling of Oakland’s warehouse culture. Due to the extra media presence at that time, each trying to scoop the other to claim “first” on discovering some hidden live/work warehouse space that hadn’t been zoned for such use by the city — always under the guise of “trying to understanding these cultures” — the locations of these spaces were ratted out. “The city of Oakland immediately started cracking down,” said Strauss. “Tons of notices and violations were issued in the week or two after the fire. People got evicted. There were tons of evictions.”

A warehouse space in Oakland’s Jack London Square by the name of Salt Lick is one example. In the days after the Ghost Ship, with the media signal-boosting any lead to fill up air-time, the owners of a barbecue place next door, Everett & Jones, held a press conference to expose the venue in a misguided attempt to, you know, “save them from themselves.” They were heavily criticized for the move by locals. The following week, the artist community and the BBQ joint “broke bread” for a benefit event held at Everett & Jones, with proceeds going to improve warehouse safety. A positive end to this narrative, wrapped up nicely with hugs and handshakes. But in the end, Salt Lick got evicted.

“It was a tragedy, then it became a tragedy on an entirely different spectrum,” said Friday. “The original was the loss of such vibrant, wonderful people. And that was forgotten and it just became about housing ordinances, and this witch hunt of warehouses.”

The hunt continues, not just in Oakland, but around the country. City governments — rather than focusing efforts on bringing warehouses up to code, of empathizing with tenants forced to live in unsafe conditions due to increasing rents and lower wages, hell, even pragmatically understanding the added value these fringe residents add to a city’s cultural cachet — are simply closing down venues, then moving on to close down the next. Two days after Ghost Ship, the tenants of Baltimore’s iconic Bell Foundry were evicted. A week after that, the punk venue Burnt Ramen in Richmond, CA was shut down. On April 27th, eight people living in an artist collective in San Francisco were evicted.

The cities say they don’t want another Ghost Ship, implying they mean another massive loss of life. But the speed at which they’re performing these evictions — and the lack of solutions they’re offering to those displaced — suggests that what they really don’t want is another Ghost Ship media event: vultures descending, camera lights illuminating the dark corners of their own institutional failures.

Postscript

Yesterday, Derick Almena, who leased the warehouse, and Max Harris, who organized the event, were charged with 36 counts of manslaughter. In a statement, Oakland mayor Libby Schaaf applauded the charges, stating “they send a clear message: you won’t get away with making a profit by cramming people into dangerous spaces or failing to maintain safe living conditions.” No word on how Schaaf will extend that message to the city’s price-gouging landlords who force people to cram into dangerous, yet affordable, living conditions like those at Ghost Ship.

Rick Paulas is writing a novel about Oakland.

Job Idea: Preëmptive Public Editors

Someone to read your column to make sure you won’t make a fool of yourself.

The other day a man wrote a not-great review of a movie he is legally allowed to be critical of but with some pret-tyyyyy bad lines:

Movie Review: Wonder Woman Is a Star Turn for Gal Gadot

Twitter predictably and rightly lost its mind over the more slobbery bits.

Today, the same man wrote a pseudoapology for some lines in the review. First of all, his title is inaccurate—“A Word About My Wonder Woman Review” is misleading; there are hundreds if not about a thousand of them. Second, the apology reads, as, well, very defensive? “I’m sorry that it wasn’t more clear that this line was meant as approving,” is sort of like “I’m sorry you misinterpreted my meaning,” which is not an apology but a sassy diss on your powers of discernment.

A Word About My Wonder Woman Review

If you have to go through, line by line, and defend your review, maybe just admit to yourself that it wasn’t your best, give it seven seconds, and move on. Maybe don’t double down on your God-given right as a film critic to dislike a film. (Sure, but that was never anyone’s point!) If you have to defend your tweet by getting into your mentions and clarifying to each person individually what you really meant, then something is probably wrong and you should step away. Like the British Secret Sevice: “Never complain, never explain, never apologize.” (There are some circumstances where apologies are welcome, but I don’t really consider either of these examples of defensive hole-digging as an apology.)

It’s almost like someone should have seen this coming. An editor, perhaps? Gray-haired media people will tell you about this position that used to exist in some places called the “top editor.” Top editing is still done, of course, but it’s more like peer review. “Hey, could you read this?” It requires humility, and more importantly trust. What I’m thinking of would be sort of like that, except what I’m after here is not top editing for content or readability or overall polish, but editing for the court of public opinion. I’m not exactly saying a Twitter editor, because there are other places people get mad online (Facebook, the comments). But yeah kind of a Twitter editor.

Last week, the New York Times announced it was getting rid of its Public Editor position as well as offering buyouts primarily to editors. As an editor, that makes me worry, because editors are in the most crucial position: between you and your words and the rest of the public reading them and maybe not understanding them. While I agree that we don’t really need people (poorly) cleaning up messes after the fact (and thus themselves creating more of a mess), I feel strongly that getting rid of the people who help prevent messes in the first place is NOT the way to go. Unless of course your copy editors are overpaid, which, somehow I doubt.

So maybe a good job in new crazy online media world would be this: a preëmptive public editor. Someone to read a piece specifically with an eye toward how others will react. Shouldn’t this be everyone’s job? Is it already someone’s job? Doesn’t it already just kind of happen de facto? Maybe, yes, but unreliably so. I wonder whether anyone at New York said anything to anyone about the Edelstein review. (I wonder why Edelstein didn’t name the female colleague who debriefed it with him.)

Sometimes those internal readers who do happen to catch something and whose voices matter most don’t feel empowered to stand up to the older established white man with a long career and many accolades. Pretty often, the person who might read something and have concerns will be an assistant, a social media editor, or a younger person of color. Shouldn’t there be someone they can warn?

I know Dean Baquet and other heads of publications need more editorial jobs like a hole in their heads, but just hear me out: a preëmptive public editor could have seen this coming a mile away. She’d be like a pre-publication Margaret Sullivan, and she has a deep understanding of the undercurrents of popular opinions online. She’s probably young, which means she’s probably cheap! And yes, she’s almost definitely a she.

A Eulogy For CAPTCHA

How do we know we’re human?

What is CAPTCHA? It’s demonic. It’s goofy. It’s at the center of a booming overseas cottage industry. It’s the most basic existential crisis. It looks cool in Russian. It’s the hold up between you and 1,000 pairs of Yeezy Boost 750s. And if it’s not keeping you from buying something en masse, it’s selling you something else: a Dr. Pepper or a Dish Network subscription or a Toyota RAV4. Also, it’s dying.

CAPTCHA, the Completely Automatic Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart, is something that should be simple but isn’t. Stepping away from any of its cultural or aesthetic significance, CAPTCHA is just a program that helps to stop spambots from spamming everything. It does this through kind of a cool trick: by mangling letters or numbers or both in a way that humans can read but computers can’t. Once the human types in the mangled words, the CAPTCHA is solved, and they can continue on to the spambot free web. And, okay, that’s a simplification, or at least a summary of a much earlier time.

At present, there are other, newer types of CAPTCHAs, and they work in slightly different ways. Some are like, “select all the pictures with a turkey.” Some are part of a larger, somewhat controversial crowdsourcing project. Some don’t show any words at all and rely heavily on your cookies. Some are actually ads. These variations (except the ad one) mostly reflect improvements in artificial intelligence, specifically in OCR, or machine vision, which type-in CAPTCHAs don’t protect against.

So it’s the old CAPTCHA, the type-in CAPTCHA, that’s going away. “Dying” if, like me, you’ll miss it, or see something important in the way it is now. “Evolving” and “improving” if not. Unlike much of what goes on in the day-to-day workings of our browsers, these type-in CAPTCHAs make themselves known to us. They’re visible, they’re interactive, by nature. Every CAPTCHA is a sort of conversation, albeit a very brief, often fraught one. And if other systems are more secure, or cleaner, or safer, It’s the act of questioning that differentiates CAPTCHA from other attempts to separate humans from bots. Even if, on the surface, the answer should be easy.

Are you a robot? No. See? Simple.

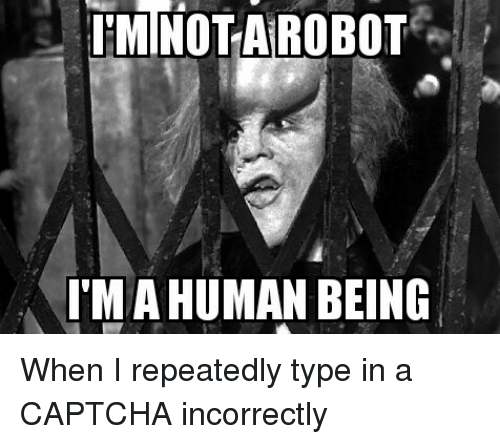

But CAPTCHA is a backronym, and like its developers realized way back in 2003, it’s hard not to ascribe some greater meaning to this wonky program after the fact. Plenty of people see CAPTCHA as a minor annoyance, get stumped and move on. But plenty more come back to it, take it out of context, scrutinize the interaction. There’s a feeling, often, of having been had. Maybe because of the look of it. Maybe because of the name, which seems to deviously combine “capture” with “gotcha.” But most of what you read about CAPTCHA online hinges on its central question: Are you a robot? Well, no. But what if you can’t read the text? Well, simple! The CAPTCHA regenerates and you try again. But what… if you still can’t read the text? OK. You fail, refresh, try again, fail, refresh, etc. Hm. Are you a robot?

It’s the implication of this impasse, more than the impasse itself, that makes CAPTCHA the source of so many things online. There are CAPTCHA memes, CAPTCHA rants, CAPTCHA comics, CAPTCHA creepypastas, CAPTCHA conspiracies, and CAPTCHA-critical fan fictions. Some of them play up the CAPTCHA’s look — the odd pastels, the slashed-up letters. Some, its content — total nonsense or cryptic phrasing like “nudism directed.” But this sort of general buzz gets at something bigger. Creepier. Something creepier, even, than the skimpy, spectral numbers CAPTCHA has you decode.

Take my favorite, “Scumbag CAPTCHA”:

And then look at this:

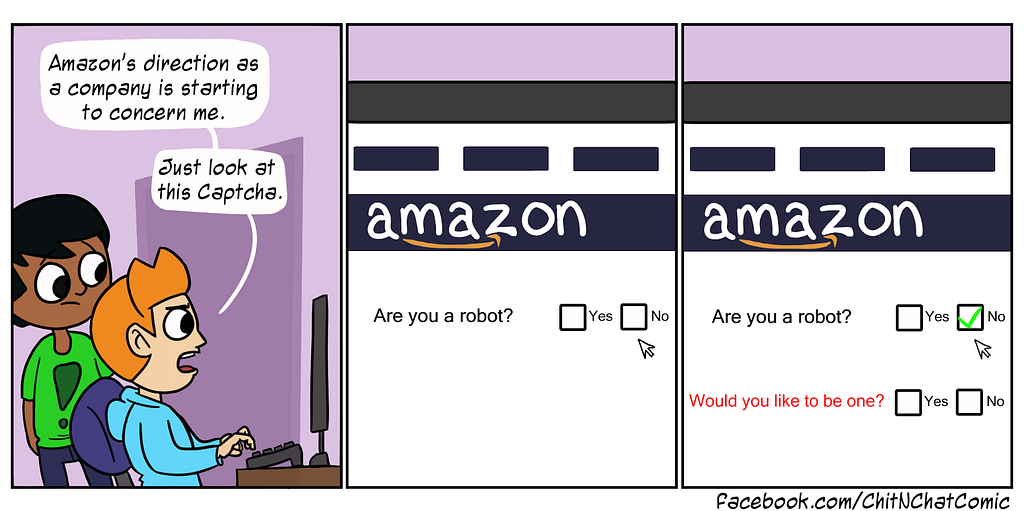

And this, on the newer, one-click CAPTCHAs:

Sure, these are pretty lame. But they’re scratching at something important. “Are you a robot?” And then, “Prove it.”

There are other examples, other things people take from their CAPTCHAs, illuminating in their own way. There are the “Robots are People Too” posters, mostly seen in fan fiction and memes. Read Le Penguin’s “A Captchaed Heart”. There are the CAPTCHA-as-demon uploads to YouTube. “Audio CAPTCHA — Performed by Demons from Hell”; “Ultimate Demon — Captcha Service Review”; “Demonic Hanicap-Accessible Gmail Audio Captcha”; and “Facebook Demon,” about an audio CAPTCHA on Facebook.

All of these things, through humor, fear mongering, or frustration, get around to questioning the things we’ve questioned always. How do we know we’re human? How do we get other people to know that, too? Is our life just some cheap, freaky simulation?

And how can you not wonder all that, looking at something like this:

So this is how we prove our humanity, by TYPEing-IN the dirty-sock arithmetic on a Tide-branded CAPTCHA. “Prove you’re human.” It’s so blah, so crass—not even a please. And the worst part: CAPTCHA was supposed to be a good thing! Reducing spam? Good! Halting the internet bot takeover? Good! Improving AI technology? Good, hopefully! Stopping one bot from buying up all the whatever and reselling it 500%? Yes! Good again! But CAPTCHA isn’t so straightforward. And through it’s question, and our often incorrect answers, a darker, more dysfunctional portrait of the internet and the economy behind it seems to tip its hand.

The problems with CAPTCHA, the reasons behind its demise, go beyond the poetic. They go straight down to the code, to the way the puzzles are written and our ability to solve them. For one, CAPTCHA isn’t serving people equally. It’s measurably harder on some than on others. In one 2010 study, “How Good are Humans at Solving CAPTCHAs?” a team of Stanford researchers finds that some people are pretty bad at solving CAPTCHAs if they’re non-native speakers. Solving time shifts around based on education levels, too. And audio CAPTCHAs — remember, those demon things? — a supposedly reasonable alternative for the blind, prove the most confusing, as the solving time jumps up to nearly half a minute. That some people have such difficulty solving type-in CAPTCHAs makes the confrontation even ickier, when you consider what’s being asked (“are you a human?”) and what might get in the way of answering it.

As hard as CAPTCHAs are on some, they’ve become much easier for the bots they’re meant to keep out. Christopher Romero, a software developer, spoke with me about CAPTCHA’s history and a bit about the program’s possible future. Romero sees a shift by the major companies towards two-factor authentication to filter out sign-up spam. This is not, again, because the tech companies are questioning the broader implications of the “are you a robot” shtick, or even because of the problems they pose for people who have trouble seeing, or reading English. The robots are just getting smarter. They can read those dumb squiggly lines better than we can.

CAPTCHA is disappearing, if not into obscurity, then at least deep behind our screens, out of sight. Take Google’s little box-click system, called “No CAPTCHA ReCAPTCHA.” Here, there are no letters. No numbers. There’s nothing to type in. No CAPTCHA looks instead at your cookies, IP address, and the movements of your mouse when you get to the screen. The program still asks the same question, but there’s no longer a satisfying answer. The conversation is gone. Are you a robot? *click*. What makes type-in CAPTCHA so poignant, so perplexing, is how in your face it is. How you’re forced to look at it, and to grapple with it. Soon, we won’t be able to see CAPTCHAs at all.

The other thing killing CAPTCHA has less to do with a machine’s drive to learn and more to do with the old adage that some people never will. These are the giant CAPTCHA-solving labor farms. Worker exploitation! Dubious legality! Flimsy and obvious industry-wide lies, promising that these companies exist to benefit OCR technology, and, uh, are for “research purposes.” Research, which does play a legitimate role in CAPTCHA development, is almost definitely not the reason “ImageTyperz” exists. So what are these companies really for? Who uses them? Really, anyone in the business of low-level, automated spamming on a large scale: pushing a product or link over and over again in comments, purchasing hundreds of tickets or shoes for resale, or opening lots of accounts for click fraud. CAPTCHA cracking is a numbers game, both in process and reward.

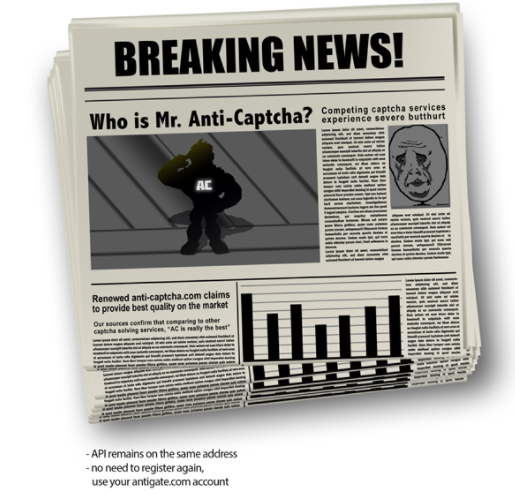

Popular sites like DeathByCaptcha, Anti Captcha, DeCaptcher, Captcha Sniper and ExpertDecoders offer “CAPTCHA bypass done right,” have 24/7 support, and “process” tens of thousands of CAPTCHAs per day, charging between 2 and 40 dollars per 1000 CAPTCHAs solved. (Interested in starting your own? There are plenty of resources to show you how.) The sites, which, again, are very professional and offer important “research” support to machine-learning developers, have lots of pictures that look like this:

The addresses are mostly foreign—anywhere from Edinburgh to Dhaka to Rostock—are and bolstered by a work-from-home labor base that extends even further. The higher-ups are just called “admins” and they aren’t quick to respond for comments. So I took advantage of the 24/7 support systems to try to figure out what goes on in the CAPTCHA farms — how they operate, and, really, to see if they’d answer.

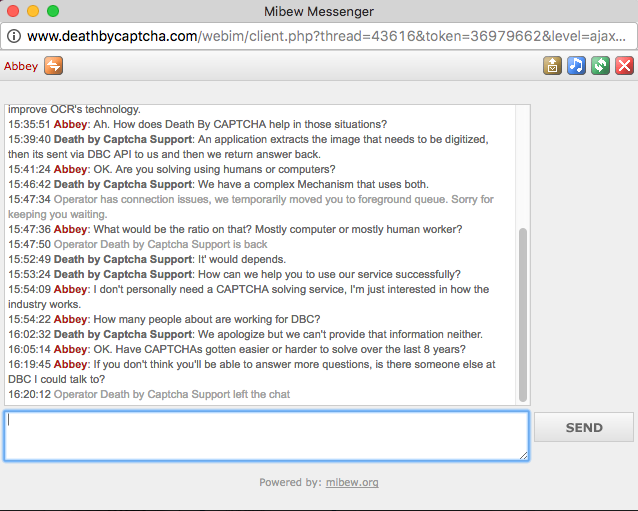

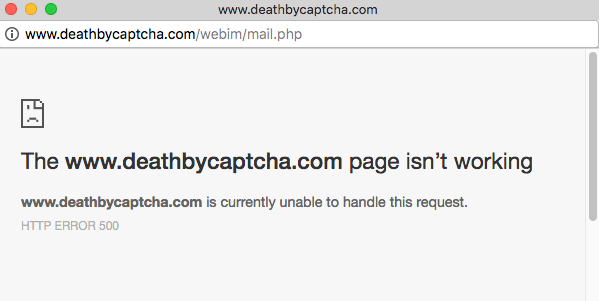

Here’s me, talking to support at DeathByCaptcha.

During our chat, which lasted almost exactly an hour (3:18 p.m. to 4:20 p.m.), I was a bit worried that my live support might, herself, be a bot. But the change in tone when it became clear I wasn’t signing up for anything convinced me otherwise.

The conversation ended, abruptly, and then I couldn’t access live support anymore.

This same thing happened at a few other sites. I was iced out of ImageTyperz pretty quickly, and got an “unusual sign in” warning from Microsoft after trying to Skype with DeCoders. What drew so many people to these classic CAPTCHAs that these farms exist? It’s the look, sure, but it’s also what’s behind it. All the ways people make money from the technology and its hacks, all the ways people scam it, only make the question feel more urgent. What is the proof of our humanity? And who wants to know?

But the question now is more one of what will replace it. Invisible CAPTCHAs are next, the logical step after No CAPTCHA. And other forms of authentication, beyond CAPTCHA or two-factor, are cropping up, which also look to answer the human question through data, instead of conversation. Areyouahuman.com is one of the companies offering a vision for the future of “Human Detection.” The flow-chart explanation for how this works is pretty opaque, but seems to be a more long-term tracking service, not designed to keep bots out entirely, but to keep them from influencing Google Analytics. Their banner ads read, “Be certain you’re addressing a Verified Human before you serve content, services or ads.” Then they boast: “Analyzing each user’s behavior in many different environments every day helps us verify and re-verify that verified humans stay human.”

Verify and re-verify that verified humans stay human. Is that better than “Prove you’re not a robot?” Worse? There’s something skeevy in answering a question you didn’t know you were being asked. And worse in not even knowing you answered. And worse still in doing it again, and again, “every day.” “In many different environments.” Exhausting. CAPTCHA, flawed as it is, is one of those special parts of the internet, like chum, that can’t help but reveal something profound in its peskiness. Better to appreciate it now, notice it now, and to critique it now, while it’s still here. While we can still see it, and talk to it. And while we can still think, in those few seconds they take to solve, about what, exactly, we’re proving.

So, CAPTCHA is dying. Here’s a video to remember it by.