Até, "Dark Days"

They all are.

This is a song called “Dark Days,” and these are the days in which we live. Enjoy.

Tracy K. Smith, Poet Laureate

Congratulations to Tracy K. Smith, named today by the Library of Congress as the nation’s 22nd Poet Laureate.

Librarian of Congress Names Tracy K. Smith Poet Laureate

Here’s a brief Q&A with the Library.

Welcome to our New Poet Laureate!

Smith has been a contributor to The Awl’s Poetry Section from almost the very beginning. Here’s ‘My God, It’s Full of Stars’ from 2010.

The Poetry Section: Tracy K. Smith

And here’s “The Angels,” from just last month.

“Poems are friendly, and they teach us how to read them,” Smith tells the Times.

New York City, June 12, 2017

★★★ The giant inflatable rat barely stood out from the darkness of the shade where it stood, surrounded by white glare. The sun came flashing down like a stainless steel cleaver. A sweaty hand reaching for change got tangled in the fabric of the pocket, sending the keys spilling to the floor. A blinding reflection came off the lid of the iced coffee. The sidewalks were visibly depopulated. A piece of litter traveled along underfoot at walking pace, driven by the breeze.

Don't Say "Pick Your Brain"

Please just say whatever you mean

it’s “pick your brain” season

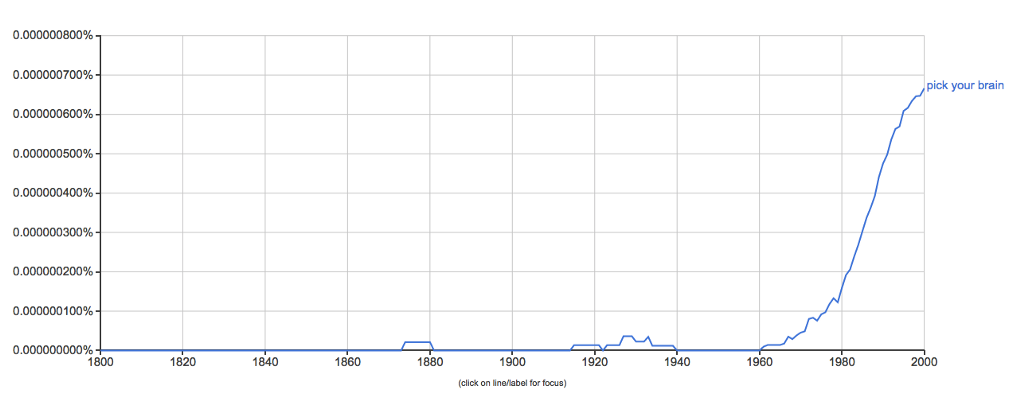

My brain is frazzled and very scabby from too many people picking at it and I’d be happy to talk to you it’s just we need a new euphemism for “ask you for something vaguely career-related (either mine or yours).” Thank you, Hairpin alumna Jazmine Hughes, for reminding me of this linguistic scourge. Before you go searching your Gmail archives: am I personally guilty of having done this before? Sure. Who wasn’t twenty-three once and considering doing a post-baccalaureate degree in order to apply to medical school so that she could once and for all get out of this toilet mess that is the New York Media Scene??? So maybe this is a PSA to twenty-three-year-olds, but according to the Google Ngram it’s definitely A Thing and it’s on the rise, and I would guess it comes up in corporate America too, if not nearly as much as “reach out.” Now that one should be ruled illegal.

Although the animus is hard to explain — and although, as we’ll see, contact has a tainted history of its own — the reasons for reach out’s steady rise are easier to, well, grasp. For one thing, reach out fills a need that isn’t addressed by any synonym. “The prime minister reached out to members of the opposition party” may mean that he phoned, emailed, or wrote letters — or it may mean all of that and more. What’s suggested by reach out are the intent and the effort.

Memoirs Of "The Greatest Living Woman Thief"

Old-School Show-Off: Chicago May, Queen of Crooks

Chicago May would be appalled by her own Wikipedia entry. “Occupation: prostitute,” the page snaps. It claims that her crimes were “mostly of a petty nature” and concludes her brief and colorless entry by saying that she ended up in Detroit “virtually destitute” and “no longer young.” But when May, in her mid-fifties, sat down to write her memoir in 1927, she presented herself as a nervy member of an international gang that moved huge sums of money across the Atlantic, an adulated con artist who almost never actually had to sleep with her victims (unlike her less skilled female compatriots), and a straight-talking crook who made so much money that she could pass as a member of high society.

By her own telling, May was a heartbreaker and a bank robber. “Well-preserved,” she claimed. And kinda sorta reformed. She had seen the light — or rather, she had seen the money, and figured that by now there was more cash in a tell-all book deal than in pulling off a few more cons. Chicago May, Her Story: A Human Document by “The Queen of Crooks” was published in the spring of 1928, but its bluster was a façade: May was destitute and slowly dying of cancer. She passed away the next year at the age of 59, thoroughly worn out by crime.

The Queen of Crooks tells us she was born Beatrice Desmond on a farm near Dublin on November 25, 1876, but other sources call her May Duignan and give her birth year as 1871. (She was probably deliberately obscuring her identity in order to protect her family.) May was the only girl in a family of seven children and was constantly getting in trouble at school for refusing to do thing she found ridiculous—like kiss the ground as a sign of penitence. By the time she hit adolescence, farm life was far too confining for her, and her parents were getting too strict for her liking. So in 1889, 13-year-old May filched sixty pounds from her dad’s money box and sailed off to America on a steamship. “It never entered my head that I might not succeed,” she declared.

She blew some of that money around New York City, reveling in the chaos, eating littleneck clams for the first time, and turning down propositions from men who assumed she was for sale. “They weren’t going to take me for a greenhorn!” she crowed. After a few weeks of this revelry, she started running out of money and headed to Lincoln, Nebraska, to live with her rancher uncle. He wasn’t thrilled to see a red-headed teenager standing on his doorstep, and so he put her to work in the kitchen; May wasn’t thrilled to work in the kitchen, and so she took up with a bunch of wild local kids. “I wanted to ride around and see the sights,” she wrote. “Not that I didn’t. Only I wanted more of it!” The hottest one of her new friends was 21-year-old Dal Churchill: “An Adonis, a model for a Greek statue.” Before long the two of them were running away to shack up together. May was just 14.

Dreamy Dal Churchill just so happened to be a member of the infamous Dalton Gang — outlaws who robbed banks and held up trains all around the West. This was May’s first glimpse into the thrilling, glamorous, and wildly lucrative side of crime: the wads of cash, the parties, and the handsome, reckless men. (“I enjoyed this part of the game exceedingly,” she says. “I liked what money could do.”) Often, the gang would send May to stay with one of their sisters in Chicago as they pulled off a heist somewhere in the West, in order to keep her out of the way. Dal, who had warned her that life with him would be “full of nerve-wracking experiences,” soon suggested that they get married just in case she got pregnant and he got killed. His suggestion was eerily prescient. Not long after their marriage, Dal went off to Phoenix to rob a train, leaving May alone in Chicago. The heist was a failure, and Dal was wounded, captured — and lynched.

It was like a switch flipped in May’s head. Suddenly, crime wasn’t just a wicked thrill, but a means of avenging herself of the entire system that had conspired to take away her man. The young widow made up her mind to become the best criminal she could be, fueled by her “deep and abiding certainty that society, as such, was my enemy.” She was already stranded in Chicago, and so she started there, moving deeper into the city’s red-light district, the Levee. “When you want to go wrong,” she mused, “it is very easy to accomplish your purpose.” It was in Chicago that she started to make a name for herself for the variety and cleverness of her cons, as well as for her nerves of steel. “The Greatest Living Woman Thief,” headlines would call her at the end of her life.

May was the queen of the confidence trick, and her victims were mostly rich, naïve men. She would lure them into a specially designed bedroom (called a “creep joint” by tricksters in the know), where another criminal was hiding under the bed, or in a trunk, or behind a greased panel in the wall. Then, once the man was undressed and occupied on the bed, May’s partner would slip out of hiding and go through the man’s pockets, replacing his thick stack of bills with a stack of similarly sized cut paper. Other times, May would play the “badger,” which meant luring a man into a compromising position by fainting and then asking that he see her home — where another criminal playing the role of her husband would suddenly burst through the door and extort money from the man for perceived wrongs done.

Many of her victims were upper-class men — rising young lawyers, for example — who couldn’t come forward and accuse May in court for fear of ruining their immaculate reputations. This meant that blackmail was often too easy to resist for May, and she would drain money from her flustered prey for months. (“What was a poor girl to do with such a sheep, baaing to be shorn?” she mused about one particularly dumb fellow.) The Chicago Tribune claimed that May changed the art of blackmail entirely by introducing a camera into the whole jig.

After exploiting the “goldmine” of innocent tourists who flocked to the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, May took off for New York to look for bigger game, traveling first class the whole way. She loved to flaunt her wealth by dressing well, reading as much as she could, and hanging out with high society whenever she got the chance. She claims that she bantered with Mark Twain and met the famous actors DeWolf Hopper and Henry Dixey. May seemed to feel that not only was she just as good/pretty/clever as the rest of high society, but she was better: a self-made woman, an individualist, able to move among the wealthy undetected. “I worked hard to make myself a master workman,” she says, and this idea of herself as an expert criminal was integral to her sense of self. She was no common thief; she would never have listed “prostitute” as her occupation. In fact, years later in a British court, she gave her vocation as, simply, “artist.”

When New York grew a little too hot for her, she sailed over to Europe and began running her business in a trans-Atlantic fashion, keeping up with various schemes in both London and New York. For example, she loved a good “breach of promise to marry” con. In those days, a proposal was considered a legally binding contract, so a jilted woman — or, in May’s case, a woman pretending to be jilted — could threaten litigation. She was able to keep these sorts of things bubbling in both cities at the same time, probably by continually sending her victims threatening letters. It was in London, in the spring of 1901, that 25-year-old May locked eyes with Eddie Guerin — a very hot, very bad news Irish-American criminal — over the casket of one of their criminal pals. “Both of us were good-looking, healthy, vigorous, well-dressed specimens of our respected sexes,” she boasted. The two of them quickly became an item.

Like May, Eddie had a temper and a lust for revenge, and he was currently mad at the entire country of France, as he had just spent ten miserable years in a French prison. Before long, he and May were hatching a plan to rob the Parisian branch of the American Express Company in order to show France what was what. The heist was initially successful, and they made off with at least several thousand dollars, but the lovers had aimed far too high with this plot. They were captured as they tried to escape on a train back to England.

Eddie was given a life sentence and flung into one of the most infamous prison in history: Devil’s Island, the “Green Hell” off the coast of French Guiana, surrounded by jungles full of predatory ants and rivers full of piranha. May got off easier; she was pardoned after two years and nine months of a five-year sentence — served in several French women’s prisons — thanks to a touch of bribery and a couple of influential friends who pulled some strings for her. When Eddie, against all odds, actually managed to escape from Devil’s Island in 1905 after about three years locked up, he tore back to England, ranting and raving. He was convinced that May had ratted him out to the police, and wanted to cut off her ears, or — May claims — douse her with acid. (“Anything to disfigure my beauty!”)

May had a new boyfriend by this point, Charlie Smith, and when the two of them ran into Eddie in the streets of London in June 1907, both men began shooting. Eddie’s gun jammed, while Charlie managed to shoot off two of Eddie’s toes. The whole skirmish was pretty harmless for this trio, but both May and Charlie were charged with attempted murder: life for Charlie, fifteen years for May. “I laughed,” says May, upon hearing her sentence, “so as to show the minions of the law that they hadn’t broken my spirit, and to show my sympathy for Charlie” — who had flung himself on the judge as if to kill him, raging with sick horror. Charlie eventually ended up in prison in California, and May would love him — and hope to marry him — for the rest of her life. Presumably, she was over Eddie, who had gone slightly mad in his green hell.

Aylesbury Prison in Buckinghamshire, England was a miserable place for an Irish lass accustomed to fine clothes, international travel, and utter freedom. There was an extremely realistic eye carved into the ceiling of each cell, with a little panel in the middle that could be slid open so that the prison matrons could peer through, and it nearly drove the prisoners mad. “You can get used to nearly anything, but you never quite got over the horror of being constantly watched,” May noted. The only positive thing about prison was that it gave her the chance to read, and she devoured everything from The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire to Dickens novels, which she loved for their hilarious portrayal of crooks. Eventually, her sentence was reduced to 10 years and she was sent packing back to the States, with her wild youth firmly behind her.

After prison, May grew increasingly existential. “What had become of the considerable sums I had filched from society?” she asked. She now barely had enough money to rent a room. She had trouble getting a job, and eventually ended up in Detroit. The once-lucky May — now in her fifties and in poor health — couldn’t catch a break anymore.

The rest of the world wasn’t done with her, though. In 1927, August Vollmer, the former head of the Berkeley California Police Department, took her under his wing — she says he visited her while she was laid up in a prison hospital in Detroit — and encouraged her to “go straight” and write her memoirs. (Seedy memoirs written by former crooks were very popular in those days, with their vague whiff of redemption and titles like Why Crime Does Not Pay. Even Eddie Guerin wrote one, called I Was a Bandit.) May was no writer, and had difficulty following a narrative through-line — her memoir jumps all over the place — but she tackled the project gamely. She and Vollmer corresponded regularly, and Vollmer also kept her updated on the status of her old boyfriend Charlie Smith, who was serving his long sentence in California.

Meanwhile, another crook was about to enter May’s life. Netley Lucas was an infamous British con man who’d been active in the 1910s and ’20s and then loudly crowed that he had reformed and was taking up journalism. By 1927, he was schmoozing around New York, where he’d just published a book about famous female criminals called Ladies of the Underworld. It was there that his publisher came up with a genius PR plot: Netley Lucas and Chicago May should get (fake) engaged. The press went wild over the odd couple, noting gleefully that May was a good thirty years older than Lucas. The American Weekly declared melodramatically that the “greatest living woman thief” was now the aging muse for this youthful “student of crime.”

May, who used to love the spotlight, trudged dejectedly through this final burst of notoriety. “I am sick and weary of life,” she wrote to Vollmer, and begged him to reassure Charlie Smith that the engagement wasn’t real. Lucas noted with shock in his own memoir, My Selves, that May was no longer the “beautiful adventuress” of days past — instead, she lived in a hotel room full of booze and cigarettes and dirty magazines, dying of cancer, and “soliloquizing in maudlin fashion over the past.” But the notoriety of the fake engagement helped her find a publisher. Her memoir came out in the spring of 1928.

By 1929, she’d moved to Philadelphia to have an operation for an “abdominal disorder,” and it was there that she was finally reunited with Charlie Smith, who’d been released. The two old lovers hadn’t seen each other for twenty-two years. They made plans to marry—perhaps dreaming of a deliciously normal, crime-free future together with a house and a dog and a garden—but May was much sicker than she or Charlie realized. She died in the hospital so unexpectedly that the nurses didn’t think to call Charlie back to her side until it was all over. “I have loved her for more than twenty years,” said Charlie, on hearing the news.

There’s no soaring redemption at the end of May’s story. The heady days of crime were long over, and she’d watched most of her friends become addicted to dope or simply sink into destitution. (Guerin, who outlived her by eleven years, died poor and obscure.) Crime had been her life’s work, the only job on her resume, but she was living proof that sometimes it added up to nothing at all.

The book ends with a recitation of facts about herself, carefully calibrated to portray a specific type of brave, cultured, autonomous womanhood: she doesn’t like to get drunk, but when she does, she gets drunk on whiskey; her favorite liqueur is Amer Picon, a bitter orange aperitif from France; she speaks English, French, Portuguese; she’s not a kleptomaniac, but likes the security that money provides; she is “well-preserved” and proud of it. She was sick while she wrote those words, but you wouldn’t know it. “I have had no regrets — except when I was caught,” she writes. “I am not really sorry I was a criminal.” Even with death hiding somewhere in the room, waiting to trick her, Chicago May admits no defeat.

Sounding Out The Science Of "Gaydar"

What the research shows, and what it doesn’t.

Since it showed up in the American lexicon in the early 1980s, gaydar has been a slippery concept to pin down. The portmanteau of “gay” and “radar” clearly signifies a purported ability to detect homosexuality in others that’s not openly expressed, but there’s no consistent belief on how it functions. Many seemingly talk about it as a holistic a sixth sense as broad and vague as extra-sensory perception. And just like ESP, it seems like something that will get tossed around in pop culture and be embraced by a portion of the population almost as an act of faith, but will always be too squidgy to attract a more critical gaze than the occasional (fairly flip) think piece.

But academics have been trying to determine whether humans can implicitly detect each other’s sexualities, and if so how, since at least the 1980s too. For at least a decade they have explicitly probed gaydar by that name. And while most scholars agree that there are, on average, some notable differences between gay and straight populations, there’s still fierce debate as to whether gaydar is a legitimate concept, or a faulty social tool that leads to more harm than anything else.

For observers like Cornell University psychologist Ritch Savin-Williams, “whether we want there to be gaydar or not is irrelevant; the science is too strong to deny its existence.”

A big chunk of this research, which tends to focus on the ability to identify gay men, argues that gaydar is a process by which people pick up on behavioral cues learned of explicitly or implicitly through exposure to gay culture and the reexamination of social presentation and roles that often comes with a coming out process. Prominent gaydar researcher Nicholas Rule of the University of Toronto argues this often manifests in the way gay people adorn themselves, act, sound, and physically carry themselves; research around this idea doesn’t support stereotypes like the gay lisp, but does identify, for example, a distinctive sway of the hips in many gay men or swagger in gay women. The notion that gaydar ties to learned cultural behaviors is seemingly buoyed by parallel research showing that people with more exposure to or immersion in gay communities can spot homosexuality more easily than others and that closeted individuals are harder to spot.

Another slice of research, which can be hard to stomach for those who see sexuality as a social construct largely independent of biology, suggests gaydar may correspond to real and inherent physical markers of sexuality. In 2007, journalist David France, drawing heavily but not exclusively on the work of California State University at Fullerton psychologist Richard Lippa, catalogued a litany of features scientists have suspected may be disproportionately common in gay people, such as left-handedness, ambidextrousness, counterclockwise hair whorls, and different densities of fingerprint ridges on the thumb and pinkie finger of the hand. More recently, researchers have suggested that certain facial features or symmetries may be more common in gay populations and easily recognized by other humans on a gut, immediate level. This research corresponds to a belief among some scientists, dating to the controversial works of neuroscientist Simon LeVay in the early 1990s and still backed by a number of studies, that there is a genetic component that correlates to and perhaps causes homosexuality — itself a troubling position to many as the quest for a discreet cause of homosexuality has so often historically coupled with or empowered a noxious impulse in society to excise it.

Gaydar skeptics don’t doubt that differences likely do exist, to a degree and in at least a portion of the gay population. But as University of Wisconsin-Madison psychologist and prominent gaydar hype critic William Cox points out, gay and straight populations have a lot in common too. Savin-Williams adds that seemingly distinctive homosexual traits picked up by gaydar can also show up in straight populations, and supposedly defining straight traits in gay populations too; this crossover may become more common as gender and sexuality labels and norms continue to buckle. “The gaydar myth,” argued Cox, “exaggerates the real differences to make gay and straight people seem more different than they actually are.”

Although he believes in the reality of gaydar, Savin-Williams questions the methodology behind many studies purporting to show its existence, especially the size and representativeness of the populations of detectors and detectees used in them. He also questions how these studies can account adequately for concealed homosexuality or queerness that doesn’t fit well in a straight or gay binary. (Genetic theories of homosexuality can struggle with liminal sexual identities as well, although some might argue that latent or partial genetic clusters may be at work there.)

Cox is critical of the fact that gaydar research is almost always conducted in labs rather than the real world. These studies show subjects controlled images of populations that are usually half self-reportedly straight and half self-reportedly gay. (This is a useful research tactic, as it’s hard to tell if subjects have identified people correctly or incorrectly in a real world setting where the researchers may never be able to find out themselves, and where they may not be able to tell or control what in a person their subjects were analyzing.) Research subjects may judge correctly in the lab a statistically significant amount of the time, but their success rate still hovers around 60 percent. Through a little corrective mathematical jiggering, Cox says, we can see that, in the real, world gaydar that seems to perform better than chance in a lab would be wrong most of the time. “Across a variety of perceptual tasks,” he said, “people tend to be fairly bad at detecting rare targets.”

“Sometimes researchers acknowledge that their studies won’t translate to the real world, but that caveat is often buried deep in their papers,” he continued. “And the more prominent claims, in the title or abstract of the paper, is that people can accurately perceive sexual orientation.”

In Cox’s view, a warped focus on our ability to detect differences that papers over the practical inaccuracy of that ability is dangerous as his research shows that once people hear gaydar is real they take it as license to engage in more blatant stereotyping. “People receive that message and overgeneralize it to a slew of different subjective definitions of what gaydar is,” he said.

The pull between “gaydar is real” and “gaydar is fake” headlines can be tricky to navigate. Science does suggest that there are detectable differences between gay and straight populations, although just how reliable or broad they are is unclear. And because gaydar is in the zeitgeist, as are questions of sexual and cultural difference, it’s entirely valid for academics of all stripes to probe these issues and our reactions to them. But no decent human wants that work and its findings to encourage what David French referred to as a form of latter-day phrenology, nor the notion that the genetic roots of these differences can be identified and possibly destroyed by those who opposed sexual difference, or the broader utilization of stereotypes.

Ultimately though, this tension may just come down our lack of a solid cultural definition of gaydar. If we had one, then we might not be so quick to label real but limited findings, with no proven real-world applicability or relevance to the way we think about gaydar, as proof that the concept exists overall. We might be more willing to accept the notion of difference and similarity commingling in a way that can occasionally tip someone off about another human’s sexual proclivities, but cannot be relied upon or taken as a meaningful heuristic for anything else.

Or we might abandon it as a concept altogether and just focus on exploring the differences and similarities, and what they tell us about the acculturation and genetics of sexuality outside of this larger and culturally freighted term.

“Most guys I know of all sexualities tell me it is the look in the eyes,” said Savin-Williams of the colloquial use of gaydar, “a lingering, a longing that tells them if someone is not straight.” Cox often hears this too. If that’s what gaydar really is, he said, then “you aren’t detecting the people who are gay. You’re detecting the people who are attracted to you,” or whom you’ve decided to focus on. “A friend of mine once called this the ‘ugly people don’t have gaydar’ approach.”

Human Sacrifice, "Family Style"

Guatemala Diaries, Part III

I went to see the Mayan ruins at Tikal, near Flores, in northwest Guatemala, but if you’re looking for real information about them this story will not provide it. Just to situate you: Tikal is the something largest Mayan site in the Mayan world, which spans Guatemala, and some other countries close to Guatemala, which definitely include Honduras, and some other countries. What else can I tell you about Tikal? It was further from our hotel than I thought it would be, has bad coffee, and the other people on our tour provided me with mild amusement.

We got in the van first: M., Alexis, her boyfriend, and me. Then a Mexican woman and her boyfriend got on. They were in their thirties, stocky, decent looking. The woman had prominent, sexy teeth. I never spoke to them but the woman sat next to me and she kept getting text notifications and I wanted to explain to her that adults were not allowed to have phones that made noise and considered combining this information with a compliment about her teeth to increase receptivity but never quite formulated a plan.

Then two young German girls got on. One of them had a cursive tattoo across the top of her back that said SHINE ON. The other one was blonde, composed, with the longest neck I’ve ever seen. I sensed a past in ballet, childhood dreams dashed.

We were crammed full at this point and I was just resting my eyes and settling in when we stopped again and I became aware of a woman shouting, “You can’t just cram us in there like cows.” She pronounced her words with the Spanish th, as in “Guatemala eth un dithastre.” She was in her sixties, soft in the middle under a tank top and shorts, with an at-home dye job, but it was obvious that she’d once been a great beauty.

“I have never in my life seen such dithorganithathion as I have seen in Guatemala. It has been one thing after another.” She continued to complain as the driver made some calls. Her husband, El Greco in cargo shorts, was dwarfed by her and the enormous camera around his neck. “Tomorrow we are going to Mexico,” she finished, “And it can’t come soon enough for me!”

Our guide was named Carlos. He was thirty— I know this because he wrote out the year of his birth, 1987, in Mayan numerals — with light eyes, strong arms, a little gut, and whitehead next to his mouth I very much wished to point out to him. He spoke extremely clear, slow Spanish, with helpful kindergarten-teacher gestures. He was interested in Mayan culture, but seemed to be almost as interested in bugs. He showed us an ant whose bite would make our whole body hurt, and a spider that would kill us, or maybe it was vice-versa. We stopped to watch a stream of what I assume were normal non-homicidal ants cross the path. “It’s going to rain,” Carlos told us, pointing to the clouds and wiggling his fingers. “The ants all huddle together when it rains.” He cupped his fingers into an imaginary ant huddle.

We stopped at a ceiba, a tree sacred to the Mayans. “Its branches represent the heavens,” Carlos said, pointing up. “The roots represent the underworld,” he said, and pointed down. Each German girl took a picture of the other posed identically: one arm around the tree and the other on the front of the tree, as if touching its chest. I wanted to hit on the ceiba tree too, but was afraid it might think I was too old for it.

The Spanish lady had gone on a different bus but ended up on our tour. It wasn’t long before she sidled up to me. “Quieres caramelo?” she said. She had flirtatious eyes. For any men reading this who are really stupid, this does not mean that the Spanish lady wanted to scissor with me in the Mayan ruins and was hoping my price was a caramelo. (Though honestly, friends, who among us hasn’t done more for less?)

I tried to refuse the caramelo, but she wouldn’t let me, and we talked as I unwrapped and ate it. “Hablas lindo español,” she said, which was a lie. I started taking Spanish in 1983 and have spent probably two years total of my life in Latin America and I still speak Spanish like a four-year-old — a really dumb one. I once had a boyfriend in Uruguay and when I met his abuela he told me that she thought I was sweet and very pretty, but possibly slightly retarded, by far the most thrilling compliment I have ever received.

I told the woman I thought Guatemala was just fine and I hadn’t had any problems thought I was certainly sorry to hear that she had. She launched into a long story about meeting a friend of theirs from El Salvador and how they tried to rent a car and how the car was late and then the car was really dirty and naturally the friend was embarrassed, and I didn’t see why because honestly other than a few stray words I had no idea what she was saying to me because as I said I don’t really speak Spanish for shit. If everyone spoke like Carlos, slowly, sticking to a single subject, it would be great. But this lady was using all kinds of idioms and generally all over the place. She finished the story, or she seemed to, because she stopped talking and looked at me significantly. I shook my head and said, “Que bárbaro!” which means, “What a pain” or “How terrible!”

I talked to the German girls for a while but they were a bore. They told me they were from Hamburg. I told them I wanted to visit Hamburg because I liked rivers, knew two people who lived there and had once read a very good detective novel set there. They smiled politely and left the conversation to take more pictures of each other.

The coolest part of Tikal was the giant plaza with several structures around a huge expanse of grass. Carlos told us that only rich people could come to this plaza and I was relieved to hear yet more evidence that the world has always sucked. Carlos told us one of the buildings was a hotel and I walked around it for a while because I really like hotels.

One of the Mayan hotel rooms was covered with graffiti. Anytime you found a spot where people could hide themselves from “the authorities” at Tikal, you’d find graffiti. “People have no respect,” the Spanish lady said, clucking her tongue over “Angela 2014” and “Nicholas 2008.” She went on. “I know some people in this country want to work. Like Carlos, he is good. But some of them…” She shook her head.

Later, she found an empty beer bottle on the path. Cursing humanity, she handed it to Carlos, who had to carry the thing around until he found an ancient Mayan trashcan.

My mind was blown once and that was when we climbed to the top of Temple Four — George Lucas’ inspiration for the planet Yavin 4 in Star Wars — and looked out over the canopy of trees. I felt like if I leapt off, I’d just land on top of them, sink into greenness and sleep forever. The Spanish lady’s husband took a lot of photos. I asked him if he got a good one, and he just shook his head and murmured, “Que canopia maravilla,” which I understood.

One of the last things Carlos taught our little group was that while the Aztecs and the Toltecs killed people on the top of their giant temples, “The Mayans never, ever sacrificed anyone this way, in public. Nunca, nunca, nunca. The sacrifice was private. It was in the family. It was in a building with four walls, and one door.” He held up four fingers, drew a square with his hands, and mimed opening and closing a door. “Any questions?”

Before we got into our separate vans, the Spanish lady found me again. She lay a manicured finger on my arm and looked soulfully into my eyes. “I speak a little English,” she murmured. “Did I hear you telling your friend that your bag was urinated on during your bus trip from the capital?”

“Oh, no,” I said, trying to look confused. “You must have misunderstood.”

Joseph Shabason, "Aytche"

Man, you won’t believe what kind of one it is.

Maybe today will so hot that people will be all, “You know what? It’s too hot to be a buffoon on social media. It’s too hot to be so stupidly loud. It’s too hot to be this incessantly irritating. It’s too hot to even open any of the platforms on which I am always such an annoying abundance of idiocy and self-aggrandizement. It’s too hot to do anything but sit silently and stare into space.” Wouldn’t that be nice, if everyone just shut up and stared into space today? Let’s hope it is indeed that hot. In the meantime, here’s something from Destroyer saxophonist Joseph Shabason. Enjoy.

New York City, June 11, 2017

★★★ The dryer added its heat and dampness to the thickness creeping in from outside. The late-morning breeze was still tolerable in the shade, and it was possible to carry a birthday present uptown by hand without sweating through the paper. A bare-chested man wrestled his way into a t-shirt in the middle of the sidewalk. Soon enough even the shade was disgusting. Sun came straight through the subway grate at 72nd Street and glanced sideways off the roof of a train, casting a blinding glare onto the uptown platform. Hosed-down sidewalks baked dry in no time. The hot, lurching wind, all its prior virtue lost, reached down behind a strolling couple and flipped the hem of the woman’s dress up past the waist. A man sat slumped on the edge of a tree-planting bed, his pale and tattooed torso exposed, unmoving. The sinking sun slipped behind a rooftop structure long enough to get the blinds facing it to open, then came blazing out the side again.