Orbe, "Somebody Bring Me Here"

So much for that.

Let’s make a deal to not talk about this week anymore and pretend that next week will be better even though we know there’s no way that’s possible. Deal? Deal. Okay, here’s music. Enjoy.

Against Personal Politics

We’ve abandoned politics for consumption.

Once, as a way of summing up his feelings on Che Guevara, my college history professor warned, “All of you wearing Che T-shirts are the first ones he would put against the wall.” I assume he meant to criticize my classmates for their devotion to radical politics, but in retrospect it seems equally apt as a criticism that they were not devoted enough. And while I’m not fond of summary executions, that interpretation seems more to the point today, because the tendency to reduce politics to a matter of acquiring certain properties has only grown.

Since Shepard Fairey convinced a generation of activists to adopt Obama’s visage, designers and artists flock to create special-edition apparel for candidates and movements, and slogans are printed on anything that can be sold in an online store, both for profit and not. “The modern practice of feminist activism has become inextricably tied to what we buy and what we wear,” Leah Finnegan wrote in the perfectly titled “Nevertheless, She Bought a Shirt.” The same is true for racial justice, environmental justice, even economic justice.

Social justice campaigns are key facets of the world’s most rapacious brands, so of course corporations and capitalists would find ways to subsume politics to the market. There’s even a certain appealing logic to it: issues like climate change and white supremacy are so pernicious, so pervasive, that what else can you do but buy organic T-shirts, witty mugs, and flashy bumper stickers? Even critics of this most capitalist brand of activism tend to offer only a different, supposedly more authentic kind of consumption as the alternative. Don’t buy sloganed shirts at the mall, prove your conviction by purchasing them directly from marginalized communities! Subscribing to the New York Times isn’t true activism, buying a Safety Pin Box is!

Though of course we should welcome material benefit going to the oppressed, doing so through purely market-based methods means accepting the right-wing ur-narrative. If it really works, then justice really does come from entrepreneurship, and if only we got our branding right, we could have full communism tomorrow.

There’s always some asshole trying to profit from any worthwhile endeavor, and left-wing politics isn’t any different. If the problem ended there, we could have our mocking fun and move on. But even today’s most genuinely praiseworthy political movements fall into the same fallacies. They may not hock material goods, but only because they hock immaterial ones — knowledge of your privilege, your identity as an ally, some life-changing awakening. What else would you expect from the generation that champions “‘experiences’ over stuff?”

Take Standing Rock. In a report from the last days of the protest, Awl pal Jay Caspian Kang concluded: “Dissent can propagate quickly now, but it also means that every protest, however specific and physical in its conception, ultimately gets reduced down to a generic feeling.” It’s those feelings we increasingly cling to, in the way we might also cling to a branded, organic cotton throw. And because the protests did not stop the pipeline, “the historic legacy of what happened at Standing Rock,” as Kang said, “will have to be parceled out through small, personal victories.” Not, the implication goes, by stopping future pipelines.

The same thing happened at Occupy Wall Street: big claims about ending inequality morphed into reflections on what individuals learned, how they’ll remember it. The Women’s March was praised and condemned both for how individuals felt in its crowds, not whether it’d help a movement take power, as Keeanga Yamahtta-Taylor has argued. The final measure is what experiences, memories, knowledge individuals acquired, and little more.

Of course, these things do matter. But if they are all that matters, then that douchebag in college who would only quote Das Kapital was more enlightened than you, and the corporate HR departments paying thousands for antiracism trainings organized by boutique consulting firms are the militants in a new world order. To state the obvious, that’s simply not true: self-satisfied proselytizing is a dead-end (and not just for its pedagogical failings), and your payroll rep isn’t the harbinger of an egalitarian utopia.

What’s missing in these views is everything outside of an atomized individual’s scope — structural inequalities, massive wealth discrepancies, the distribution of power — and any sense of whether we can change what we find there. This brand of personal politics can offer insight only into how individuals experience those structural problems, not into the construction of the problems themselves, and thus not into how we can overcome them. We’ve abandoned politics for consumption. We have a host of personal essays when what we need is one good, compelling manifesto.

That doesn’t mean we should echo those dudes on campus carrying Das Kapital who ramble on about how if only people had class consciousness. People went to Standing Rock and Occupy and Ferguson to address specific, widespread problems; we fall back on personal victories because we keep losing, and if any experience or idea was powerful enough to defeat the cops and their dogs and the rest of the Right’s tools, we wouldn’t be losing in the first place. And with Trump and his band of Disney-villain Republicans leading a blitzkrieg of regressive campaigns, we’re only going to keep losing unless we figure out a better strategy.

Ironically, Marx still has the most compelling answer, precisely because he insists class consciousness isn’t something individuals can develop on their own. All his talk of the proletariat as the agent that would overcome capitalism wasn’t because he thought the working class was somehow more oppressed, or more aware, or more intelligent than any other oppressed people. His point was a strategic one: what is important is that when the masses entered the factories, they were, for the first, time working side-by-side in one place with, well, the rest of the masses. There were lots of them working together, building relationships, and they were doing so in places they could use for leverage — stop the coal mine or the one train track running into a city in 1860 and you suddenly find yourself with a lot of power. It’s not that we should fetishize the proletariat, it’s that Marx’s logic was sound; we must find the places where we can turn existing relationships into sites of power. To stop commercializing politics, we must start politicizing daily life.

Today’s dilemmas are compounded by the fact that unions have been on the decline for decades, contract and remote work are further separating coworkers, and people are either locked out of work or forced to work longer hours. On top of that, schools are being resegregated, community programs are being defunded, and the public sphere in general is under attack, increasing the alienation and isolation of individuals, making it ever harder to form the kind of powerful collectives that offer a way forward. No wonder radical politics has often drifted into an activist subculture pining for a past protest, and no wonder civic engagement — like attending unthinkably long, boring city council meetings — is left to the rich and the ideologues.

But there are some creative, grassroots approaches to organizing that are rebuilding the kinds of community that can wield power. A number of municipalities around the world have responded to resurgent right-wing movements by forming “rebel cities.” They’re creating minimum-wage laws, antidiscrimination ordinances, and similar local legislation to support their citizens. But those cities could go further, taking a cue from the sewer socialists, who, back in the early 1900s, created publicly owned utilities, grocery stores, and more. Do that, and simply by living in the city you’re helping fund community endeavors. Add in experiments with public banking, new public housing, and expanded community programming, and these cities could spur a robust, integrated community that could form a base of power from which to grow.

Local politics can often devolve into politicking and influence peddling, especially when state laws prohibit cities from enacting any strong legislation, so new democratically run, cooperative, community-owned developments are key. Nowhere is that clearer than in Jackson, Mississippi, where Cooperation Jackson has been creating a network of worker-owned businesses. In these cases, political organizing is built in the fabric of the community: if your neighbors get their child care from a worker-owned cooperative in the neighborhood, backed by a community credit union, then child-care becomes an explicitly political issue that the co-op can leverage. The same is true for unions, as the Chicago Teachers Union showed when they went on strike in 2012, stopping life in the city and earning broad community support. The fact that Cooperation Jackson has used these projects to build a base for a movement that just won its second mayoral election is proof that these approaches can build power in traditional political arenas as well.

With Trump’s nativist corporate agenda looming, it’s also important to build underground networks to protect the most vulnerable, who are essential parts of our communities. That means organizing neighborhoods — especially gentrifying neighborhoods — to physically interrupt deportations and protect the undocumented, granting sanctuary in the short term and creating ways to recognize their residency legally in the long term. It means creating groups that can help women get safe abortions if Roe v Wade suffers a fatal blow, or in places where abortion is functionally outlawed thanks to TRAP laws and other right-wing legal tricks.

These approaches help bring a political register to the problems people are already living, where they’re being lived. It’s turning a lunch-time bitch-fest with your coworkers into a union meeting, providing some organization to help it grow and knitting individuals into collectives with power. It’s more essential than ever, because Trump reigns only if Thatcher still does, too: the only way a chintzy, billionaire real-estate developer could fashion himself as a populist revolt in the first place is if there is no alternative to capitalism. Resisting Trump without resisting Thatcher’s legacy leaves us with the meager comforts of new T-shirts, memorable experiences, and fragile identities. To win more than that, we must transform our already existing community bonds into the core of a political movement, whether through state-supported programs or — when voter suppression and gerrymandering prevent us — institutions we build ourselves.

Matt Hartman is a writer from Durham, North Carolina.

Down by the Old Mainstream

How to play Spotify.

Among Farley’s most popular pseudonyms is the Toilet Bowl Cleaners, whose “The Poop Song” has been streamed more than 400,000 times. But just because the song’s about poop doesn’t mean it’s shit, as Farley told Vulture. “Take a listen. These are real songs. I know they’re about poop, but I’m proud of them. They’re actually good,” he says.

There are so many amazing details in Adam K. Raymond’s piece on how artists (or “artists”) are manipulating Spotify that it’s hard to choose just one, but c’mon, “The Poop Song.” It’d be harder not to choose that one. Anyway, you will enjoy this.

How Spammers, Superstars, and Tech Giants Gamed the Music Industry

Has No One Told The Tumblr Girls About Gustav Holst?

First things first: Gustav Holst was a Virgo.

Okay.

Lots has been on my mind lately! I’m thinking back to Rimsky-Korsakov’s adventurous Scheherazade, but also about the types of loud triumphant music played over the Fourth of July weekend. Music made popular by, well, pops orchestras. And then it dawned on me that I had yet to come anywhere close to our sweet friend Holst and his Planets.

Composed between 1914 and 1916, and finally premiering in 1920, Holst’s The Planets was a seven-movement orchestral suite about, uh, the planets. He was British; this stuff is always pretty straightforward with those folks. It wasn’t intended to be scientific, nor was it rooted in Roman mythology. This was purely astrological, which is why it felt essential to tell you that Holst is a Virgo. Of course this ought to start making sense now. He frequently consulted a book by astrologer Alan Leo (who was, yes, a Leo) called What Is A Horoscope And How Is It Cast? in order to subtitle each of the movements. And he did horoscopes for his friends! Extremely nice. And cool. I’m thrilled to announce that Gustav Holst is also now my friend. (I am an Aries — is that not clear?)

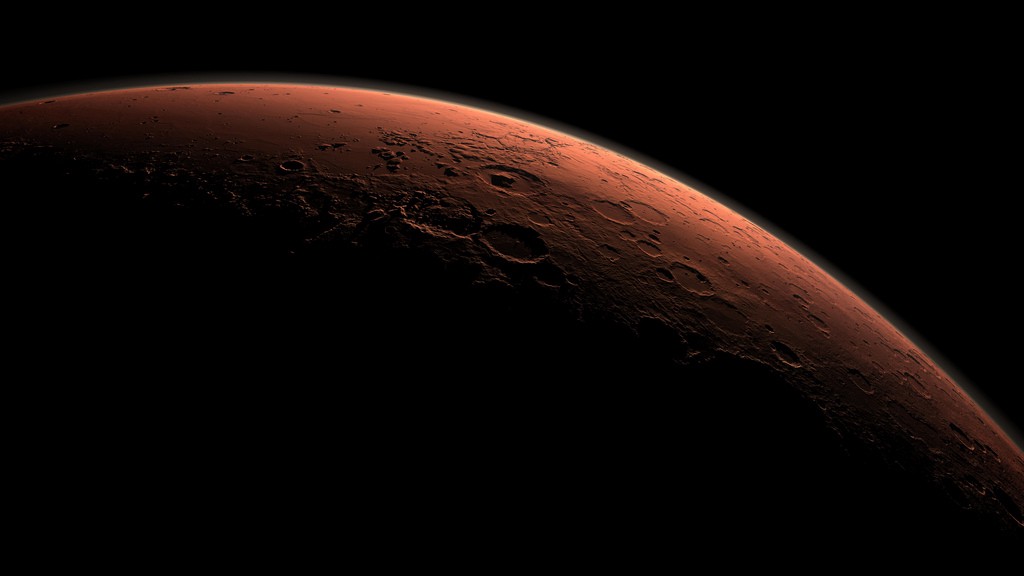

We’re going full Bernstein this week, using his 1969 recording. So, like any good horoscopes section, Holst’s Planets begins with Mars, the Bringer of War (or, you know, Aries). This is the most popular movement of the suite, and if you know any of them, it’s probably this one. It’s very prevalent in pop culture, see?

It’s got a deeply memorable militaristic drive to it. It opens with a droning clicking noise that may not sound like an instrument you’re familiar with, but it’s actually the string players hitting their strings with the wooden side of the bow. I played timpani on Mars, which was a fine thing, but with some distance, I’ve learned to really appreciate the strength and richness of the brass without having to constantly count out my own part. Mars is the only movement of The Planets I’ve played; like I said above, it tends to be isolated and played by younger orchestras or for bigger pops events. That’s fine, no doubt, but taking it out has always felt wrong. On one hand, I don’t think it’s significantly easier of a piece, and on the other hand, Mars is much less annoying (sorry!) when contextualized within the other planets.

Like Venus, the Bringer of Peace. This is the longest movement in The Planets and one of the most thoughtful and elegant. For all of Mars’s repetition, Venus feels much more broad in its sound. It begins quietly, thoughtfully, with the French horn. It takes time to establish itself, encroaching almost cautiously into the listener’s eardrums after the pounding melodrama of Mars. I’ve always been fond of the violin solo at the 2:17 mark and that melody that follows on the strings. It floats just on top of the orchestra with a lightness that somehow also has body and depth to it. It’s an antidote, truly, to the movement before it, and a cleansing balm going forward.

Mercury, the Winged Messenger is a straight-up goofy piece of music with some fucking crazy-ass wild percussion throughout. Remember when Hermes was voiced by Paul Shaffer in the Disney’s version of Hercules? Look, I know that’s Greek, and this isn’t that, or Roman, or scientific, but c’mon. Listen to this movement and tell me you don’t hear a little flying jazz band conductor. This sounds like Paul Shaffer without sunglasses.

Ah, and now we’ve come to the crème de la crème, Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity. There’s no official structure to a seven movement orchestral suite the way there is a sonata form to a symphony. But Holst said that The Planets were intended to mirror the stages of life, consider Jupiter prime adulthood A.K.A. feeling sad and weird on Friday nights and quitting your job. I love love love this movement. It is, to me, hands down the best. It does, in fact, bring jollity!! To me!! Even when it slows down a bit at the 3:04 mark, there’s an overwhelming heroism to the music. It’s deeply optimistic, summoning a joy from further within than the passive kind associated with Top 40 radio.

From here we enter something of a musical denouement in the fifth movement, Saturn, the Bringer of Old Age. Isn’t that just how these things go, you’re spry and fun for a second and then you’re old as all heck? Saturn is an odd movement, a real dramatic shift. It’s certainly less memorable on its face: there are no big hooks to Saturn like there have been in past movements. It feels wise and old, troubled and conflicted. Its sound is more abstract than its prior movements, a big reminder, to me, that this is 20th-century music. It’s getting weirder. More modern. More troubled. Saturn really comes into itself right around the big crescendo right past the 4-minute mark. At 4:44, there’s an unsettling back and forth between the strings and brass and percussion. It sounds like a horror movie!

Uranus, the Magician follows with a big, brassy announcement of itself. The magician is here, folks. Please log the hell on. This is some Sorcerer’s Apprentice-sounding shit. There’s some xylophone here that would make our old friend Saint-Saëns proud. Uranus is exciting, a genuine thrill ride throughout. It’s letting Holst go full weird which, this late into the suite, honestly rules. It’s possible on this listening that you’ve taken the Planets very seriously. That’s fine, but please don’t forget this is a guy who used to read people’s horoscopes for fun and is a Virgo. You’re meant to enjoy this. It’s supposed to unsettle and amuse you.

The final movement of The Planets is Neptune, the Mystic. For those (nerds) demanding (like nerds do) to know where Pluto is, the answer is: Pluto wasn’t discovered yet. And so, the end of The Planets manages to feel inconclusive without even trying. Neptune is a sweeping and haunting finale. There’s a women’s choir that features throughout, representative, in my guess, of the mystic herself. It really does sound like an old-fashioned version of a ghost. You have expect there to be a creak of a hallway (maybe it’s just my apartment though). It’s hard to classify The Planets as a piece of music, impossible to nail to a particular mood or feeling or state of being. It ends with a fade out, something we’d view as a cop out these days, but for the time it was written, feels unresolved in a deeply artful way. Space is infinite, you know? And Holst is a Virgo. Don’t forget.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.

Don't Sext Me In The Present Tense

The many moods of sexting

“Aren’t tenses in sexting weird?” I asked my long-distance boyfriend one morning (he studies linguistics). He had noticed the weirdness of the verbs of some of our more raunchy conversations — it turns out he had been thinking the same thing every time he had sent me so much as an aubergine emoji.

Communicating about sex, like a lot of actual sex, is a kind of negotiation, a dance between blunt statements of longing and the careful clarity to ensure that you’re not totally embarrassing yourself. Both of us would use lots of tenses to communicate our desire, but one thing we could agree on was that the present tense was to be avoided at all costs. Just like IRL sex, we don’t really know how other people are doing it until we do it with them — that’s part of the mystique of a crush. Were other people sexting in the present tense, we wondered? As my boyfriend hypothesized about “illocutionary force” and “universal necessity modals” (hot), I took a more straightforward path and started a Twitter poll. “DIGITAL SEXERS: what tense/mood do you sext in?”

I set the poll to 24 hours and waited, ready for the responses of all varieties of the past, conditional, future, and they rolled in (people REALLY like talking about sex on the internet, it turns out). “2–3 different tenses per conversation would be optimal, imo,” said my friend Kiona, who suggested that linguistic variety would be indicative of an exciting sex life. “Conditional/future mix,” said someone called “Tsunami tha Wave.” I am sad to report, however, that my followers contained a contingent of those absolute perverts: sexting with a repulsive and oppressive immediacy that is conveyed solely in the present tense.

Let me explain. We don’t use the present tense to describe what we’re doing in the current moment that often in English. We barely ever use the simple present in particular (e.g. “I fondle, you choke, we moan”), apart from when we describe mental states (e.g. “I imagine, you want, we yearn for”). In that specific kind of sexting that involves using the present tense to create a sext-story, the narrative is built up in an unusual way. This makes present tense sexting sound like a genre, a format for using language that comes with expectations about context. That genre, my friends, is roleplaying. That’s right — you are doing the same thing as a fifteen-year-old boy playing Dungeons and Dragons.

As Glasgow law student Alice Caldwell-Kelly pointed out to me, this is the joke in the now-antiquarian meme “I put on my robe and wizard hat” (chat-room cybersex goes wrong when one user starts role-playing as a wizard). The meme is a fiction, created by an internet humor site called Fugly, but its narrative shows the linguistic echoes in the ultra-present language nicely:

bloodninja: Oh yeah, aight. Aight, I put on my robe and wizard hat.

BritneySpears14: Oh, I like to play dress up.

bloodninja: Me too baby.

BritneySpears14: I kiss you softly on your chest.

bloodninja: I cast Lvl. 3 Eroticism. You turn into a real beautiful woman.

BritneySpears14: Hey…

bloodninja: I meditate to regain my mana, before casting Lvl. 8 Cock of the Infinite….

“I think there’s an idea of sexting as a format,” Caldwell-Kelly told me. As the creator of the @sextsbot account, she would know. The Sextsbot sends out filthy little moments of nonsensical debauchery — random, code-generated shots of lust. Although there’s the occasional future (e.g. “I’m going to put my suspicious tracksuit in your dick”), and quite a few imperatives (“Please climb my viral zine”), mostly, they’re in the simple present. “I fondly email you in the metaphorical titties,” it might sputter out, one Tuesday morning. “You bite down on those testicles like a lesbian band.” “I put my human rights in your tonsils, baby.”

It’s genius, and it works because we know what the idea of a sext looks like. They are bald and immediate in their desire. There’s no masking or flirtation in these sexts, they’re all pumped-up, demanding sex drive. Kind of like how the men on the Tumblr “Straight White Boys Texting” seem to imagine it works — as if chucking out a jarring demand of smut will begin a consensual sparring match of equally horny sexts.

“It’s funnier the blunter it is,” Caldwell-Kelly says. “Looking at the bot’s followers, I think a lot are the same generation as me, who probably did the exact same shut-in nerd sexual exploration before anything else and were confronted with this form of sex or flirting that’s really quite awkward and strained.”

My friend Sara tells me she’s kind of into the out-of-context sext. She likes to remind her beloved that sex with them is on her brain. She uses it less as the beginning of a mutual storytelling exercise and more of an everyday update of their sexual relationship. “So that I can keep them still thinking about me.” While she admits to using the present tense, she uses it more to state her current thoughts and desires, which we do more naturally in everyday English: something like “I want to push you up against a wall”, or “I can’t stop thinking about pinning you down on the bed and pulling your hair.”

According to philosophers of language like Jaakko Hintikka, sentences with desire verbs shift our perspective to a world in which our desires come true. Or, as my boyfriend paraphrased it: “He basically says that ‘I want to take off your clothes’ means ‘In those worlds where my desires are realized, your clothes are off.’” You can see which one looks hotter.

The present tense does have one thing on its side — brevity. When I spoke to internet linguist Gretchen McCulloch about this, she hypothesized that the number of keystrokes in itself might make people more likely to use the present tense in sexting especially as the exchange of messages becomes more excited — sexting, like its real-life counterpart, tends to have directional force. “Now I don’t have data on this but I don’t think that most people start a sexting conversation with ‘shall we do the sexting now?’ I think that it tends to grow organically out of the conversation. So if you’re saying: ‘I miss you, I wish you were here,’ this could turn into, ‘what would you do if you were here’.”

If you’re anything like my 2–3 tense-per-conversation friend Kiona, you don’t want to stay in the conditional, so as thing heat up, the tenses might flatten into simplicity. “I wonder if there’s a tendency to end up in the simplest tense, because that’s the one that takes the least effort to type,” she says. McCulloch also pointed out that we’ve developed a handy and not-weird way of theoretically enacting things in cyberspace, by using a third person present with asterisks either side. We’re used to reading Tweets that say *coughs*, *sighs* or *strokes beard*, and somehow they don’t feel at all Dungeons and Dragons-y. It’s just conventional in internet narrative. And yet, both Gretchen and I agree that this isn’t something we’d expect people to do in sext conversations, even though there seems to be a similar imaginative force behind them. *slowly pulls underwear down thighs* just doesn’t have the right ring to it.

What I, personally, would like to do is avoid any semblance of comedy, which present-tense, counterfactual absurdity can quite easily induce. Sex can appear to be a horrific morass of messy desire to anyone not involved in it, or even to the people who are involved in it, right after it occurs. This applies to communication also. By remaining outside of the simple present of role-playing, I’m trying to retain just that shred of dignity that makes the act slightly less depraved when I look back on it afterwards.

24 hours, 249 responses, and a whole lot of IRL conversations later, and my Twitter poll has proved that a lot of people on the internet have sexting habits that I find fucking weird.

DIGITAL SEXERS: what tense/mood do you sext in?

So there we are: I am, apparently, a present-tense sexting kinkshamer, as multiple people explained to me when I made extreme facial expressions at their response to my invasive sexting questioning. I suppose, in conclusion, it doesn’t really matter what tense consenting adults decide to sext each other in — or if they want to play Dungeons and Dragons as foreplay — as long as they’re not sexting me, of course.

Josie Thaddeus-Johns is a writer and editor based in Berlin. She writes for the Guardian, Frieze, Creators, among others.

A Poem by Erin Hoover

The Valkyrie

Strapped to the wheel of perpetual

awareness, I listen as my boss says, if I want

to keep my job, I’d best think hard, not about

the minutes I waste, but the seconds. So when

a man catches the ATM door behind me,

each blink I take feels like a good, long

sleep I’ve earned. I don’t notice, at first,

the worm of his moustache, butter-colored

arms starred with moles, or the side-pocket

protrusion of his gun until he motions

at it, then me, to hand him the single crisp bill

I’ve withdrawn to help me get hammered

tonight. It’s already growing soft as I wad it

into his palm, relieved to comply completely,

to be sure of doing it right. But then he says,

Take out the rest. Now, with the barrel nudging

my left lung, there it is on the screen,

in the certainty of 1s and 0s, how little

I have left. Only last night, I went home

with a guy who asked me to strangle him,

so I put my hands on his neck and squeezed,

said, No one will even notice you’re gone

in the stony voice I usually reserve for myself.

The words came easily, but how loud they were

in that musk-hot room, how his body tensed

felt new. So I move to snatch back the bill,

and my robber’s hand opens as if he expects it,

the rule that anything given in the world is soon

retracted. The gun there, still. And me,

banking on him as the kind to shove a girl

down a flight of stairs, that they’ll do enough

work to shut her up. But there are no stairs,

no hypothetical falls, just my explanation

to him that today I turned off the lights

in the supply closet to cry. How pieces of me

remain in my office cube long after security

sets the night alarm, and that some part

of me is always there, two eyes under a desk —

the same hapless Valkyrie hitching up my skirt

each morning to ride into Port Authority,

drawing against the water torture of a system

that owns my sword, portions out my rations,

and his. His hard face breaks into pity, eyes

and jaw relaxing. He puts the gun away,

a teenager in dirty jeans, skin of the innocent,

and says, Don’t tell anyone. Please. My eyes

close against the war drum of our twinned

pulses. The wheel stops for us. It finally stops.

Erin Hoover is the author of Barnburner, selected by Kathryn Nuernberger for the Antivenom Poetry Award and forthcoming in 2018 from Elixir Press. She lives in Tallahassee, Florida.

The Poetry Section is edited by Mark Bibbins.

Balmorhea, "Clear Language"

Did you forget how much things sucked?

If we are working on the assumption that the main point of this short week — if we are in fact working on the assumption that any week can be short these days, given what’s going on — is to re-acclimate ourselves to the horror of the weekday after a brief but blissful respite from reality, then I think we can all agree that everything we’ve seen in the last day or so has gone a long way towards helping us reestablish our familiarity with just how fucking awful everything is all the time, but especially when we’re at work. Here’s some music. Enjoy.

New York City, July 4, 2017

★★★★ Figures bustled on balconies in muted light. Then the day clarified and the sky became thin blue, empty over empty sidewalks. The plan had been to take the subway to the bookstore, but in the space of the first few steps toward the station, the children agreed to an about-face and a fifteen-block stroll instead. People stood separate and individual in their compact midday shadows, never cohering into a crowd. With a bag full of books, the walk back lost its appeal; a downtown train arrived at once, and the air conditioning on it was working tolerably well. Up on the street a tall, lean man and a short, broad-shouldered one drifted closer together as they reached a corner, their shadows clasping hands a moment before they themselves did. Clouds came back to break up the afternoon sun. The five-year-old blasted a tennis ball, bright and springy from a newly opened can, wide right and all the way over the top of the 15-foot playground fence. It rolled across the driveway there and into the shrubbery, a dozen yards or three sides of a block away. After the trek across the playground, up the street, down the avenue, and into the apartment complex, it took some searching to find it glimmering in the darkness of the plantings. A moment of wind and gray came on, a half-made threat of rain quickly abandoned. New blurry clouds caught the western sun on their soft edges, then were replaced by a denser sheet, but one with daggers of sun poking through it and more sun glowing past its far edge, the daylight irrepressible. Routinely spectacular colors spread—a gold glow going over to lilac, a stroke of red in the middle of darkening purple-gray. A huge patch of brightness appeared near the top of the mirrored tower across the avenue. It was the color of the moon, but it seemed too big and too powerfully lit. Then it faded for a moment, exactly as the moon fades when a cloud crosses it. A quick trip down the elevator and out to Broadway revealed the moon directly, gibbous and high up. The clouds around were now the color of ivory, now the color of smoke, against a sky still uncertain between day and night.

You Shouldn't Be Snorting Anything But Allergy Medicine

Definitely not chocolate

Supposedly, the result is a Red Bull–like endorphin rush that lasts 30 minutes to an hour without the side effects of a sugar crash. Though doctors admit they haven’t done tests on Coco Loko’s effects yet, because “snortable chocolate” wasn’t really something on the medical community’s radar. However, one ENT doctor warns that there are “a few obvious concerns.” First off, it’s “not clear” how much chocolate the nose’s mucus membranes can even absorb. Also, Coco Loko might “create a paste that could block your sinuses,” which sounds uncomfortable while it’s in there and disgusting once it comes out.

Someone Invented Snortable Chocolate

Related news: Clint Rainey continues to have the “stunt food story” beat over at Grub Street. Somebody’s gotta do it.

Did Amway Create the Gig Economy?

“Once again, it is the Law of Compensation.”

“This is just Amway and Avon all over again. But idiot me, I still drive.”

Amway is a fifty-eight year old multi-level marketing (MLM) company that sells soap, laundry detergent, and health supplements. Last year, it began insisting that it was part of the gig economy. Jim Ayres, head of business operations for Amway in North America, says direct selling isn’t just a gig, but one of the best gigs out there. “Take a look inside the ‘gig economy’ and what it means for YOU” shouts the Amway Twitter account. On their official blog, direct-selling is identified as a common type of gig economy job, right alongside ride-sharing and home-sharing.

Thus far, these efforts haven’t paid off with a seat at Code Conference or the Aspen Ideas Festival. The only people to echo Amway’s claims are gig economy workers themselves: search “Amway” on Uberpeople, a popular forum for Uber and other rideshare app drivers, and hundreds of threads pop up. “Lyft and uber is Amway on wheels,” wrote one user. “Uber is this generations Amway, without those annoying monthly checks for recruiting a superstar performer,” wrote another. “Funny you mention Amway. I wouldn’t be surprised if the two corporations merged. They seem to have many similarities,” wrote a third.

Amway was founded in 1959 by Jay Van Andel and Rich DeVos, father of Michigan gubernatorial candidate Dick DeVos and future father in-law of education secretary Betsy DeVos. The two friends had been involved in several business ventures before becoming independent distributors for Nutrilite, a vitamin supplement developed in the 1930s. Dismayed by how Nutrilite sellers competed amongst themselves for clients, DeVos and Van Andel formed Amway, which would use a more sophisticated multi-level marketing scheme to sell Nutrilite supplements, detergent, nail polish, and other household items (later, they would buy Nutrilite from its former distributor, Mytinger and Casselberry, Inc.). In his 1993 book, Compassionate Capitalism, DeVos notes that Amway was founded the same week Fidel Castro overthrew Fulgencio Batista in Cuba. “It has been just thirty-four years since Castro took over Cuba promising prosperity in reform,” he wrote. “Today most Cubans live in poverty and despair…. Amway, on the other hand, became a four-billion-dollar corporation.”

To say those billions of dollars were earned by selling soap is an understatement; Amway’s success hinges on its byzantine marketing structure. You can buy products directly from Amway’s website, but most products are sold through its distributors — independent contractors who buy their stock from the company or from the person who brought them into the organization, known as their “upline” distributor. Today, distributors can sell their wares at whatever price they see fit, though this was not always the case (price restrictions were key to the Federal Trade Commission’s complaint against Amway). Amway has always noted that signing up distributors carries no monetary bonus, and that signing up distributors is not necessary to earn a profit with Amway. Substantial income, however, requires a significant “downline” of distributors.

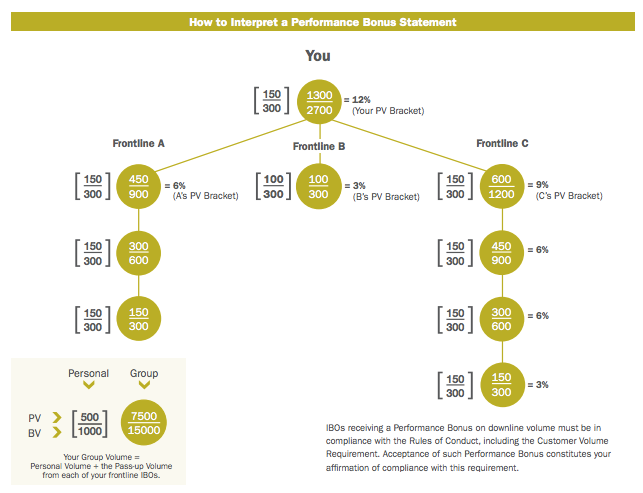

Each Amway product has a Point Value and a Business Value, the latter of which is a fixed dollar amount. Even if you manage to sell Amway’s detergent for $1000 a pop, its business value will remain the same. Every month, distributors add up their point values, then see where it fits into the performance bonus schedule: the higher your point value (PV), the higher the percentage of the business value you receive as a bonus. Larger bonuses can be earned by signing up other distributors, or adding them to your “downline”; in calculating your monthly PV, you add up the PV of your downline distributors along with your own. If your eyes are glazing over, just listen to Sammy Hall’s “Circles, Crazy Circles,” a song about the diagrams shown to prospectives; according to former distributor Stephen Butterfield, Hall’s songs were regularly played at Amway rallies.

Since the big bucks almost always require a large downline, and distributors on that downline can only earn the big bucks if they develop downlines of their own, Amway has been accused of being a pyramid scheme, since its distributors would presumably run out of people to recruit. But in 1979, the Federal Trade Commission found that though Amway’s price fixing “would probably violate the Sherman Act,” its organization was technically legal (in an initial decision, an administrative law judge reasoned that in areas where population growth outpaced distributor growth, there was little reason to worry). As the New York Times business columnist Joe Nocera observed in 2015, this ruling allowed later MLM firms, such as Herbalife, to legitimize themselves by modeling their business after Amway.

At first glance, the company couldn’t be more different from Uber. Uber is cosmopolitan, global, and hedonistic to a fault. Amway is short for American Way — DeVos and Van Andel are so studiously Midwestern that they commissioned Norman Rockwell to draw their portraits. But if the gig economy is just “ordinary tasks, but codified and structured such that a billion-dollar company can be built on top of them,” then the companies are in the same boat. As a Bloomberg reporter observed in a recent article about Avon, a similar multi-level marketing company, “selling jewelry and make-up on the side isn’t really so different from driving an Uber.” And just as Travis Kalanick broadcasted his affinity for Ayn Rand, these two Calvinists also embraced free-market capitalism to a degree that would make Max Weber weep. “Life, like it or not, is a harsh regimen in which rewards are contingent on behavior,” DeVos wrote in his 1975 book, Believe! “That is not an artifact of capitalism; it is a rule of nature itself.”

Performance-based bonuses aren’t unusual, but what makes Amway’s structure of bonuses distinct is the lack of any base pay or safety net (DeVos’s comments on the “rule of nature” come after a critique of job security and across-the-board wage increases). Amway’s distributors only earn when they turn a sale, with no provisions for effort or time invested in the company. Though Uber puts on a friendlier face, the performance-based model is the same. According to Uber’s website, “You can drive and earn as much as you want. And, the more you drive, the more you’ll make.” In April, New York Times labor reporter Noam Scheiber contended that Uber’s faster pickup times meant drivers were spending more time idling without passengers — time for which they receive no compensation. Uber disputed that claim.

In both companies, distributors are responsible for any costs they incur while doing their job, which may drastically reduce earnings. In his autobiography, Amway co-founder Jay Van Andel sneered at the people who lose money through Amway, blaming it on their purchase of expensive video equipment to help sell goods (a nearly identical anecdote can be found in 1985’s Promises to Keep, a laudatory book about the company written by frequent Amway chronicler Charles Paul Conn). After the Super Bowl this year, Travis Kalanick infamously yelled at a driver who claimed he had lost $97,000 driving for Uber, saying that “some people don’t like to take responsibility for their own shit.”

The idea that employers are not responsible for their employees predates Uber or Amway. But Amway pioneered a way to package that arms-length relationship between a company and its workers, and the way they sold their vision is nearly identical to the way Uber and other gig economy companies pitch themselves.

The pitch for driving for Uber is clear: “You like the idea of choosing your own hours, being your own boss, and making great money with your car.” “With Uber, you get to set your own schedule and you only have to drive when it works for you. There’s no office, no boss, and you’re in charge.” The nature of that appeal is familiar to anyone involved with Amway. “Income opportunity, flexibility in hours and location, and independence from an employer, all with low barriers to entry,” a 2016 company blog post read. “These are benefits that Amway has been offering for decades, long before anyone ever uttered the term ‘gig economy.’”

Though Avon may have beat them to the punch, there’s a surprising amount of truth to that claim. Amway distributors, DeVos tells us in Believe! are “working for themselves.” A ’70s Amway guide for distributors urged them to tell prospects that “Amway can offer you an opportunity for true independence. Freedom from time clocks…. [F]reedom from allowing someone else to decide your financial progress.”

These advantages are stressed most of all, however, by Charles Paul Conn, a freelance writer and professor with a peculiar relationship to the company. Conn co-authored DeVos’s Believe! in 1975, then wrote five purportedly neutral books about Amway (The Possible Dream in 1977, The Winner’s Circle in 1979, An Uncommon Freedom in 1982, Promises to Keep in 1985, and The Dream that Will Not Die in 1996). These books occasionally contained disclosures about Conn’s relationship with DeVos and usually contained sentences like “the money is there to be earned, and many people are earning lots of it” (from The Possible Dream). “I guess the book does lack a counterpoint,” Conn later admitted.

In An Uncommon Freedom, Conn writes of how Amway distributors might be granted “freedom from the alarm clock, the commuter-bus schedule, the nine-to-five drudge.” Earn when you want, chill when you want, Uber promised in 2016, but Conn was making similar promises decades before: “Much of the appeal of the system, as opposed to other more conventional part-time jobs, is that the distributors have the choice of working as much or as little as they like, when they like, and be paid accordingly,” he muses in The Winner’s Circle. In a 1980 commercial, part-time distributor Gordie Howe made the same promises about Amway: it’s a flexible part-time job that’ll earn you extra income. Incidentally, Howe’s other promise — that you’ll “meet new people” — is also made by Uber, which often highlights the fun people you’ll meet on the job.

Both companies have promised great wealth. During rallies in the 1970s, DeVos would tell audiences that they should start “thinking in terms of making $100,000 a year because you can do it and you ought to think that way.” Uber notoriously stated that the median driver in New York made over $90,000 a year. Lower earnings, both companies explained, were due to contractors who voluntarily worked part-time. In a 2015 speech, then-spokesman David Plouffe stressed that many of Uber’s workers fell into this role. “It’s just driving an hour or two a day, here or there, to help pay the bills,” he said. Van Andel, in his autobiography, explained that many distributors saw Amway as “solely a part-time occupation — something to bring in a little extra cash every month.”

But the most curious feature of Amway and Uber’s pitches to prospective users is that they create small businesses. In Believe!, DeVos applauds the “two hundred thousand independent Amway distributors working for themselves.” Summing up Amway’s affairs in 1993’s Compassionate Capitalism, he boasted that there were “more than two million independent distributors who own their own businesses.” In An Uncommon Freedom, Conn describes Amway members in the exact same terms, calling them “independent distributors who own their own business.” Business lobbyist Richard L. Lesher, who headed the U.S. Chamber of Commerce for 21 years, echoed this in 1997, writing “the small business revolution is here to stay… Amway is in the vanguard of that revolution.” (If Lesher’s devotion to Amway wasn’t clear enough, those words appeared in his introduction to “Amway: The True Story of the Company That Transformed the Lives of Millions,” an authorized history of the company written by Wilbur Lucius Cross).

Uber has harped on this point with even greater vigor. In a 2012 interview with Washingtonian, Travis Kalanick stated that “we’re connecting riders and drivers. They are not our cars and not our drivers. They have their own companies, or they’re freelancers.” A year later, Kalanick wrote a blog post where he called Uber’s drivers “transportation entrepreneurs.” “As an Uber driver-partner, you ARE an entrepreneur!” says one driver in an interview featured on Uber’s website. “Now I feel like I am a small entrepreneur,” laughs another driver in an Uber ad. Uber’s commitment to the “entrepreneur” label is reflected in its many legal actions, some of which seek to stop drivers from being classified as employees and some of which simply distance the company from its contractors: when a six-year-old was killed by an Uber driver in 2013, Uber denied any liability because the driver was off-duty. Later, the company settled for an undisclosed amount.

But even ignoring the absurdity of billion-dollar companies claiming they’re really in the business of making businesses, “becoming an entrepreneur” hardly describes either the Uber or the Amway experience, since both companies sharply restrict how their “entrepreneurs” can do business. The app, in Uber’s case, does not allow drivers to set their own rates, and may shut off access to passengers if their rating drops below a certain level. Amway’s rules of conduct forbid distributors from selling to anyone they did not personally sponsor or selling Amway products in any kind of retail establishment.

Both Uber and Amway’s marketing schemes have led to actions by the Federal Trade Commission. In 1979, though the FTC declared that Amway was not a pyramid scheme, they did order the company to stop misrepresenting the amount its distributors can make. Central to the FTC’s judgment was Amway’s frequent use of $200 as a typical monthly business value; in 1973–74, the actual average was $33. As a result of the judgment, Amway must prominently disclose the amount made by average distributors (according to a September 2016 document, the average monthly gross income was $183). In 1986, the company had to pay $100,000 for violating this order.

Uber, meanwhile, paid $20 million to the FTC in 2017 over misrepresentations of the amounts its drivers could make; the complaint cited Craigslist advertisements that promised earnings far above the median amount earned by drivers, along with the infamous assertion that the median income was over $90,000 a year in New York and $74,000 per year in San Francisco. In The Possible Dream, Conn claims that the FTC has filed complaints against “just about every other American company that has managed to show a profit during the past few years.” This defense, meager as it may be, would not work in Uber’s case.

“I think Uber will be regarded in a similar way to Amway in the future,” one Uberpeople user wrote in 2016. But the question of how Amway is regarded depends on whom you ask. While never losing its punchline status in some circles, Amway became one of the most well-connected companies in American history. Conn claims that in 1965, then-Congressman Gerald Ford read DeVos’s “Selling America” speech into the Congressional Record. In 1973, Ford attended the opening of Amway’s Center of Free Enterprise. As president, he invited DeVos and Van Andel to the White House. Jesse Helms and Ronald Reagan spoke at Amway rallies in the 1970s (George H.W. Bush would later be paid $100,000 for an Amway speech).

In 1981, President Reagan attended the opening of the Amway Grand Plaza Hotel, along with Nancy Reagan; Gerald and Betty Ford; George and Barbara Bush; Henry and Nancy Kissinger; Lady Bird Johnson; Secretary of State Alexander Haig; and Pierre Trudeau. When Haig left the White House, he began consulting for Amway.

In Compassionate Capitalism, DeVos offhandedly mentions that he served on Reagan’s AIDS Commission (in Promises to Keep, Conn wrote that “gay rights… are still not popular causes at an Amway rally,” and during his time on the Commission, DeVos said that homosexuals wanted to “capture the agenda”). Ford, Haig, and Reagan’s surgeon general C. Everett Koop all wrote praise-filled blurbs for Compassionate Capitalism. Van Andel and DeVos donated $2 million each to the Progress for America Voter Fund, a 527 committee supporting George W. Bush’s reelection campaign. And as Politico noted in January, Rich’s son Dick DeVos used the family fortune to reshape Michigan politics following a failed run for governor in 2006; his wife, Betsy, is now the Secretary of Education (in Believe!, her father-in-law writes “…the next year I went to a public school. I didn’t like it there.)

In his 1975 book, DeVos railed against communism, affirmative action, Ralph Nader, and creeping atheism: he notes that there is a “difference between the company of Christian people and those who have no faith” and that “this country was built on a religious heritage and we’d better get back to it.” When he wrote Compassionate Capitalism 18 years later, he adopted a warmer tone and narrowed the subject matter: aside from some puzzling asides on evolution, the book largely focuses on economic issues.

DeVos’s sunnier demeanor makes sense; on this issue, he had won. Even if Amway’s business model was suspected, the company-contractor relationship became accepted. The idea that a company’s workforce could be made almost entirely out of non-organized, non-salaried workers who are entirely responsible for their own supplies, health insurance, and other expenses was alien when Amway began in 1959. Today, those ideas are said to be the future of work.

Uber’s recent turbulence — the sexual harassment disclosures, the dalliance with the Trump administration, the file on a rape victim that an exec carried around for a year — may well sink the company — it has already forced founder Travis Kalanick to step down. But that collapse would not end the business of ride-sharing; competitors like Lyft or Curb would swiftly move in. The degree to which DeVos’s ideas have been accepted can be gauged by the number of Obama and Clinton acolytes who have left to work for the gig economy, as Nathan Heller recently noted in The New Yorker. Most prominent among them is David Plouffe, who joined Uber in 2014 and left this January. Plouffe, who ran Obama’s 2008 campaign, should be diametrically opposed to the far-right DeVos (in 1981, DeVos said that critics of Reagan had a “limited mentality” and had been “trying to destroy our country for some time.)”

Here is what DeVos wrote about wages and benefits in 1975:

“Job security, if it means that a man cannot be fired no matter how poorly he performs, can be just another way of avoiding accountability. Automatic, across-the-board pay increases often provide for workers to be rewarded equally, regardless of their competence, and thus nullify the usefulness of meaningful evaluation.”

And here is what Plouffe said in 2015, when Ezra Klein asked him if Uber was profiting from wage stagnation in America:

“There’s no doubt if people were getting 10% raises every year, you know, maybe they’d feel a little less need. But that’s not reality.”

For DeVos, the benefits that unions fought for constitute a moral crime. For Plouffe, they’re just not realistic. There is a world of difference between those philosophies, but they’ve arrived at the same result: gig work. And if these two agree, hey — something must be going right. As DeVos writes in Compassionate Capitalism, citing two of his favorite thinkers: “The apostle Paul and the dog Snoopy are both getting at the same idea. Once again, it is the Law of Compensation: Do good! Work hard at it! And you shall be rewarded!”

Petey Menz is a writer in Connecticut. He can be reached via email.