You're Popular

The median Twitter account has exactly one follower. http://t.co/XlrrwrP2HM pic.twitter.com/cgBw1aOChl

— Jon Bruner (@JonBruner) December 18, 2013

“In comparative terms, almost nobody on Twitter is somebody: the median Twitter account has a single follower. Among the much smaller subset of accounts that have posted in the last 30 days, the median account has just 61 followers. If you’ve got a thousand followers, you’re at the 96th percentile of active Twitter users.”

Why The Ideal Creative Workplace Looks A Lot Like "Fraggle Rock"

by Elizabeth Stevens

Karen Prell performing Red Fraggle at Comic-Con. Photo by krysaia.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of “Fraggle Rock”’s first airing on January 10, 1983. In the spring, the cast and crew got together for a reunion in Toronto, where the show was taped. They gave toasts, performed songs, and ate well into the night. There was a Marjory-the-Trash-Heap cake topped with intricate sugar-paste Fraggles and Doozers that fed over a hundred people.

While most of the participants were getting on in years, two guests had not been old enough to work on “Fraggle Rock.” Mark Bishop, the CEO of Marvel Media, and Matt Wexler, former executive producer at Spin Master Entertainment, both gave speeches attesting to the profound effect “Fraggle Rock” had on them at a young age. “Fraggle Rock” gave a lot of people the impression that they could do what they love for a living, and many of them now do.

Elizabeth Stevens’ Make Art Make Money: Lessons from Jim Henson on Fueling Your Creative Career is available now for Kindle. Her history of The Muppets is available online.

But many don’t. Corporate work culture has become particularly toxic in recent years. In August, a twenty-one-year-old intern at Bank of America Merrill Lynch died from a seizure after performing eight all-nighters. His internship was paid, and that is a rarity. Last year, it came out that an account executive at Goldman Sachs called his clients “muppets,” apparently meaning “clueless.” This Thanksgiving brought the infamous Walmart employee food drive for fellow employees. In many companies, there are an array of methods for expressing disrespect for clients, bosses, employees, or even the company’s mission. It’s not really surprising when that mission is, at the end of the day, just accruing money.

I’ve spent the last few years researching Jim Henson’s business practices as an antidote to this corporate wasteland. In my search, I came across a statement that I just couldn’t shake. According to Dave Goelz, the performer who plays Gonzo, there was a familiar refrain at every reunion: “Over and over we heard them say it was the best job they ever had.” From 2013, it sounds like one of the Storyteller’s Fraggle tales: too good to be true.

I asked Jocelyn Stevenson, one of “Fraggle Rock”’s co-creators, about this. She is compiling a behind-the-scenes book due out next year. Everyone she interviewed told her: “Fraggle Rock” was the best job they ever had. I asked the show’s producer Larry Mirkin, too. “Almost everyone who worked on the show has said that,” he said, “and that’s not an exaggeration.” It’s hard for me to imagine such a workplace actually existed. But it did.

Why was “Fraggle Rock” the best job so many people ever had? Co-creator Jocelyn Stevenson gave me five words.

Vision

“Fraggle Rock” “was made in service of a compelling vision,” Stevenson said. When Jim Henson brought together the three people who would ultimately create the world of “Fraggle Rock” — head writer Jerry Juhl, designer Michael Frith, and writer Joceyln Stevenson — he told them he wanted to make an international show that would “help stop war.” His initial producer on the project, Duncan Kenworthy, said that everyone “almost laughed” at him, because “it’s such a — on the face of it — impossible, enormous, grandiose sort of idea.”

Henson not only made an anti-war show, he did it with a light hand and silliness. The episode “Fraggle Wars” deals with McCarthyism overtly (“My name is Mokey Fraggle, and I am not now nor have I ever been a member of the enemy Fraggles”). But most of the time, the message is imperceptible; it was written in the structure of the show’s universe. In the show there are three species that don’t see eye-to-eye, both figuratively and literally. The Doozers were “knee-high to a Fraggle,” and the Gorgs were sheer giants. In DVD interviews, Kenworthy explained that “Fraggle Rock” modeled how conflicts could be “loosened” by exploring each of the different points of view involved. Adults may be a lost cause, but “the children,” he said, “could understand the Gorgs… the Fraggles… the Doozers, and see why they couldn’t understand each other.”

“Fraggle Rock” was made a few years before the toppling of the Berlin Wall and aired in countries across the world (the United States, Canada, UK, France, Germany, Spain, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and eastern Europe). It was key that the show rejected the “good versus evil” thinking of the Cold War, and introduced the idea of being a global citizen to an emerging Millennial generation during their most formative years. Did Henson stop war? No, but he may have helped change the attitude of the next generation. The very fact that the show had a compelling mission — this dream of peace — made it a peaceful place to work.

When employees feel that their company doesn’t do good, or that it takes advantage of people, they are more likely to act of out of selfishness or self-interest. People stuck in such corporate treadmills work to pay a mortgages, not to achieve a beautiful vision. I think anyone would much rather work at a place like “Fraggle Rock,” where, as Henson said, “trying to do something that makes a positive statement… brings out the best in a lot of people,” and gives them something they’ll be “proud of for a long time.”

Karen Prell, the performer who played Red Fraggle, described the philosophy at “Fraggle” as “very different than a lot of productions. A lot of productions are conflicts and egos. In our case it was just thrilling to see what heights we could get to with everybody’s input.” If you want to teach children about conflict resolution and world peace, it’s important to model that behavior in the way you make your show. The show’s producer, Larry Mirkin, said everyone at “Fraggle Rock” had “shared values… not just what the work is but how you do the work.” And according to him, “there was never an argument on the set.” They just didn’t have time for them. “We all just believed that in order to make the show, we were going to make it by means of this joyful process.” Essentially, the show practiced what it preached.

Creative

More than just an advertising buzzword, “creative” means you get to create, to make things. But most managers don’t feel comfortable allowing the kind of freedom that creation requires. When Jim Henson asked his team to imagine an entire world from scratch — the universe of “Fraggle Rock” — he gave them an amazing gift: autonomy. Jocelyn Stevenson called it “creative generosity. The freedom to make mistakes,” and it’s an essential component for any truly “creative” workplace.

Jim Henson was never one to rest on his laurels, and as soon as “The Muppet Show” taping wrapped in 1981, he called a meeting to talk about “the next show,” Michael Frith said. Henson held a couple meetings in a “very grand conference room in London’s Hyde Park Hotel.” He didn’t give this group a prescriptive “script Bible,” only his vision: to help stop war. “Ideas emerged pretty quickly,” Frith said, “a tribe of small, animalish things who lived behind the walls… A world began to take shape. And we laughed a lot.” This is not difficult to imagine — in interview footage, these people laugh more than anyone I’ve ever met. They talk about their work with gleeful smiles.

That’s not because they are unrealistic. Once, during a taping, Jerry Juhl said to writer David Young, “I’ve got a great idea for Doc’s workshop: Gobo steals his nitroglycerin tablets.” They never made this show, but there were several episodes about death, including a “funeral dirge you can dance to.” It was said about Henson that something that would depress anyone else would tickle his sense of humor; the people he selected also had this disposition.

Henson’s selectivity was the secret weapon that allowed him to give his chosen few complete autonomy, complete trust, in creating their art. Mirkin believes Henson’s “instincts” about people were crucial. He trusted, Mirkin said, “them, and he trusted the process… The creative process that every day starts with nothing but possibility.” He and the people he worked with had “a deep love of that place.”

What does “trust” look like? For “Fraggle Rock”, Frith said Henson “gave us his house in London to work in… a couple of the most intense, creative and hilarious weeks I’ve ever enjoyed, anywhere, on any project.” While Henson was busy working on The Dark Crystal, his merry band of co-creators made lists: “Things we know about the Fraggles,” “Things we know about Doozers.” Frith made hundreds of sketches, without much thought for limitations, and many of these things came to be. “No one ever said it would be too expensive or too time-consuming,” he said. “[P]eople just pushed through the night to make things happen — again and again. A trio of dancing giants, hundred of tiny, marching workers, dozens of furry Fraggles… endless caverns, crystalline constructions, and gleaming underground cities, a tumbledown castle, Doc’s cluttered workshop….”

The opposite of trust is micromanaging. In The New York Times, Joe Nocera noted Apple’s Steve Jobs was the kind of “micromanaging” “dictator” who demanded others work to achieve his vision and were not paid to have their own. By contrast, Paul Williams, who wrote the score for The Muppet Movie, once said Henson was easiest person he’s ever worked for. He said he’d experienced the alternative, and “It’s hard to work when the phone’s ringing every two minutes.”

When people are given the autonomy to create according to their own vision, they feel not just good but grateful. Juhl said, “He took this set of people and said you guys are gonna do this… and I’ve always been really grateful for it.” The head of the puppet building workshop, Caroly Wilcox, said something similar: “He trusted us to invent… to be given the chance to create was something Jim did for all of us, and that was a great pleasure.”

Throughout every stage of the production, people were trusted to create. Mirkin says no instructions were ever given in the script about the design of the Doozer constructions, and it brings to mind the joy of building with Tinker Toys — except that it was a paying job. With writers, Stevenson noted that head writer Jerry Juhl never took away a writer’s script and rewrote it, “which is so often done…. At the end of the show it was still your script,” she said. “The words were your words.”

Collaborative

With the rise of the Internet, there is no greater buzzword in workplaces than “collaboration.” When Steve Jobs wanted to create an atmosphere of collaboration at Pixar, he famously designed their new building to have only two bathrooms in the center, so that all of Pixar’s hundred employees would have to see each other in random interactions throughout the day. But how dictatorial is that? It’s hard to imagine having a fruitful meeting of the minds when you’re running halfway across a building with urgency. Jobs, not much of a collaborator himself, had the wrong idea about collaboration.

Collaboration can’t be compelled; it can only be inspired, by a leader who collaborates. A careful listener, Jim Henson was known to take a janitor’s counsel on occasion because “a good idea could come from anywhere.” In the 1960s, his company was a small collective consisting of Jerry Juhl, Henson’s wife Jane, and himself, and “everyone was doing everything.” It was extremely collaborative, and so it was only natural that he understood how to create this environment at “Fraggle Rock”: by selecting other natural collaborators and giving them autonomy.

Karen Prell has said that “nothing at the Muppets was done in isolation,” and even this is an understatement. The songwriting duo of Phil Balsam and Dennis Lee were selected out of a “heap” of cassettes, and were already collaborating, one dropping off a tape in the mailbox at night and the other dropping off a sheet of lyrics the next morning. Though Juhl and Henson rejected hundreds of other applicants, they never rejected a song from Dennis and Lee. Once they were selected, they were trusted.

Perhaps the best example of collaboration is in the characters themselves. A character like Gobo Fraggle comes to life somewhere between the design process and the performance. Puppeteer Jerry Nelson, for example, would look at the size of the puppet’s mouth to determine what kind of voice he had. The writers had an idea of who the characters were, but they also watched the performers improvising, and much of the banter between Goelz and Whitmire became dialog in later scripts between Boober and Wembley. With the giant Gorg characters, it goes one step further: each Gorg was the result of a mime performing big, foolish body movements and a puppeteer controlling the face via remote control.

Collaboration like this leads to a lot of laughing and silliness, and it’s easy to see why. Let’s take the process of “assisting.” When a character like Cantus has two live hands fluttering over the keys of his pipe, the puppeteer effectively needs three hands, so the right hand is actually performed by a different person than the left. Syncing up isn’t simple, but it can be magical. This is what true collaboration looks like. Think different, yes; but think three-legged race, not distant bathrooms.

“It’s actually really fun to assist because you have this exercise in just tuning in. It’s almost like becoming a radio,” Prell said. “You would surprise yourself” by seeing what “came out of two people at the same time.” Since Henson worked this way from the very beginning, he didn’t have to think of wild architectural gambits to trick people into collaborating. Henson showed everyone who worked for him that collaboration was fun.

Money

Collaboration is an expensive proposition, because with writers watching performances, performers attending writers’ meetings, and many characters being performed by two people, there are more people-hours to pay for. Jim Henson was not on set much for “Fraggle Rock” — after directing the first two episodes, he only returned occasionally. But when he left “Fraggle Rock” in the hands of his trusted few, he left them with something crucial: a lot of funding.

Larry Mirkin told me money wasn’t an issue for the production, because Henson had convinced two networks to fund the show. HBO, eager to make its first original series, gave Henson a generous amount of cash. Canada’s CBC network also supplied some cash as well as the facility and crew who filmed the show. And because Henson owned the show (instead of either network) he was able to sell it (again) to international markets.

With HBO’s artist-friendly subscription model, “Fraggle Rock” became the unlikely predecessor to “Sex and the City,” “The Sopranos,” and “Girls in the U.S.,” and in Canada it joined the innovative taxpayer-subsidized CBC lineup, which would also produce “Kids in the Hall.” Neither network, Mirkin said, ever gave “Fraggle Rock” a single script note, which was as rare then as it is today. “It is so rare,” he said, “that you have to say this.”

It would be hard for anyone to make a show like that today, even Henson. “He was at the top of his commercial game.” The Muppet Show had been a huge success, and Henson could essentially do whatever he wanted; funders were eager to share in his success. As my book details, it took many years of hustle for Henson to get to this stage — a fifteen-year side career of TV commercials, making the difficult decision to merchandise his Sesame Street characters, and using this money to garner enough exposure to land an angel funder. It was thirty years into his career, so “Fraggle Rock” was one of Henson’s most mature works as an artist.

It’s no surprise that we don’t see children’s shows today as beautiful, wise and well-crafted as “Fraggle Rock” — a show that took three hours to shoot fourteen seconds of footage because the writers think it would be funny to see Doozers on pogo sticks. The market doesn’t encourage such wastes of expenditure, but Henson had his own money and worldwide stardom, so he could afford to.

Accordingly, the producer’s job became one of diplomacy rather than enforcing budgets. After the crew stayed until six in the morning one night flooding the Gorgs’ basement, Mirkin “made a rule that we would not go overtime on Wednesdays and Fridays… People have families to get home to,” he said. Many of the CBC crew retired soon after and said working on “Fraggle Rock” was “a great way to go out.” While it isn’t always easy to get so many different people to work well together, if you have enough money and select the right people, it can be a lot of fun.

Challenging and (Incredibly) Fun

You’ve read the word “fun” enough times by now to become skeptical, as well you should. Larry Mirkin insists that “as much fun as you would hope it was to make “Fraggle Rock” because of what was on screen — it was actually more fun to do it” — “the entire time.”

But, for the “Fraggle Rock” creators, “fun” and “challenge” went hand in hand. “We were still dealing with production demands,” Mirkin said. The songwriters pushed themselves to write three original songs each week. It may seem fun to puppeteer, but have you tried to hold your hand above your head for even five minutes? For Henson, and for those who worked at ha! (Henson Associates), part of the fun was the challenge of hard work.

Jocelyn Stevenson describes “Fraggle Rock” as challenging; for her, there was a “huge learning curve.” Coming from magazine publishing, she had never written for TV before and had to learn by doing. Among the “Fraggle Rock” writers, many came from other disciplines: David Young had published a novel and bpNichol was a poet. Young was a proponent of The Gift, a book about art given to him by Margaret Atwood, and Stevenson’s literary influences included Lewis Carol and Ogden Nash. Because they weren’t TV professionals, the show’s creators didn’t think about “Fraggle Rock” as being “for children.” It was simply a show with intelligence and humanity where they could tell the kinds of stories they wanted to tell.

It can be incredibly rewarding to “rise to the challenge,” as Steve Whitmire has said about doing his first central character, Wembley Fraggle. It was “left in our hands to be the authorities about what we do on a daily basis,” he said. Today, Whitmire performs the most central role of the Muppets: Kermit the Frog. While the “Fraggle Rock” team may not have been made up of experts, they were all dedicated to doing their absolute best.

“There was an internal demand for excellence in the show that we all felt,” Mirkin said. It may not have been overtly stated, but it came from Henson himself. Jerry Juhl explained Henson’s quiet influence on those around him: “Year after year, we watched him push himself beyond what we could possibly imagine. You had to try to keep up.”

When a job is challenging, but not fun, it often stems from the leadership’s approach to other people. Steve Jobs has had an impressive impact on the world, but I don’t think he’s a great role model for creative people who want a good work environment. Jef Raskin described Steve Jobs as “impossible to work with,” failing “to give credit,” and prone to “ad hominem attacks.” At Atari, he told the engineers “that they were moronic and their designs were lousy.” The attitude of leadership sets the tone for the attitude at the entire workplace.

At “Fraggle Rock”, Larry Mirkin said, it was about “civility — behaving properly.” “We challenged each other all the time,” but it wasn’t about ego, he said, it was about “the best idea winning…. I’ve never been in a situation where a lot of tension made the work better.” As Henson’s stand-in with final cut of every episode, Mirkin was a listener and made good use of the phrase, “I don’t know — what do you think?” A lot of people, he said, are “afraid to look weak,” and feel that “I have to be in charge. I own this… but you want to work with smarter people than yourself. You don’t lose your authority.”

Part of “Fraggle Rock”’s civility may stem from having been filmed in Toronto, rather than Los Angeles. When Mirkin described unFragglish ways of working, “rat-race” thinking, “fear-based and power-based” thinking, it seems to describe an American corporate mentality.

Can we get more companies to run like this today?

No matter how much I wish I could, I can’t work at “Fraggle Rock,” because the show ended in 1986. There is reportedly a movie in the works, but this has been rumored for more than ten years.

But I’m convinced that it is possible achieve a workplace culture like “Fraggle Rock” today. “A lot of people want to work the way we work,” Mirkin said. He and Stevenson still try to work that way — the Fragglish way — whenever they can. So why doesn’t everyone?

Money often gets the upper hand of people. I want to work this way, but sometimes you just need a stop-gap job and it becomes your life. The big entertainment companies with the most jobs are the ones chasing last year’s hits and marketing demographics instead of human hearts. I wonder if the same entertainment industry that created Mickey Mouse and Kermit the Frog would be more likely to suppress such works today. For “Fraggle Rock”, money wasn’t the end goal, it was more about “what you want to put into the world,” Mirkin said. According to him, it’s still possible today, by finding the right people. “It’s your choice,” he told me. “Who do you want to be friends with?”

I asked Jocelyn Stevenson a silly question: Why isn’t every job like “Fraggle Rock”? “Because,” she said, “there aren’t many Jim Hensons around,” she said. “None, in fact!”

Henson’s business is unique, and not just among Hollywood studios. I think it’s a good reminder that it’s possible to have “joyous” workplace, but it starts with a leader who works that way. Dave Goelz has said that Henson’s films conveyed the attitude of his company, and I would have to agree. Before he died, Henson was able to “put into the world” his own, very beautiful work philosophy. This is how Goelz explained it:

“He gathered all sorts of people, in each of whom he saw something special. His company was like Noah’s Ark, loaded to the gunwales with all types, including some natural enemies. During our voyage all these different people worked together, and in so doing, even the natural enemies came to respect and love each other. That’s what is so special about Jim, and that philosophy of celebrating diversity underlies everything we’ve done. I think our audience senses that, and it means a lot to them as well. It’s a vision of a better world.”

Elizabeth Hyde Stevens spent three years searching for the answer to starving-artist syndrome by looking to her childhood hero: Jim Henson. Along the way, she created a research course at Boston University called “Muppets, Mickey, and Money,” and published her research online at The Awl, The Millions, Electric Literature, and Rolling Stone. Her book, Make Art Make Money: Lessons From Jim Henson, is available now for the Kindle reading app.

The Paratrooper Was A Dog.

The Paratrooper Was A Dog. A Dog Paratrooper. And You’ll Never Believe What He Did. (He Paratrooped.)

“Brian was a tough paratrooper. He trained hard for his deployment with the British Army during . During his training, he learned how to identify minefields. Then, on the battlefield, he protected his comrades-in-arms — though not all of them made it back. On D-Day, he parachuted under heavy anti-aircraft fire onto the Continent. He was there when the Allies liberated Normandy. A few months before the war’s end, he parachuted into western Germany, from where he marched to the Baltic Sea. Less than two years after the war, Brian was given an award to recognize his ‘conspicuous gallantry.’ But the bronze medal was not the only thing that distinguished this special soldier from the majority of his comrades:” OMG YOU WILL NEVER GUESS!

The Vaccines, "I Wish I Was A Girl"

It is the rare video that is confident enough in its song to relegate it to the background, but that is what we have here and I believe that it works. Watch and share. [Via]

2013 Music For Indie Types

If you fit a certain demographic profile that matches up fairly closely to my own — with the significant difference being that you are not so locked in your ways at this point that you cannot muster up the energy to allow new music into your life — this seems like a pretty good Best of 2013 list to make some choices from.

Your Insatiable Desire For Adorable Kitty Videos Is Killing Your Plants

Your wireless router could be murdering your houseplants, but I guess that is better than developing houseplants that have evolved to not only survive but thrive on the radiation from your wireless router until they gain some kind of sentient physicality and strangle you to death in your sleep because they are sick of watching everything you use your wireless router to see. I mean, that is going to happen eventually anyway, but it would be nice if we had a few more years before it did. [Via]

The Politics Of The Next Dimension: Do Ghosts Have Civil Rights?

by Matthew Phelan

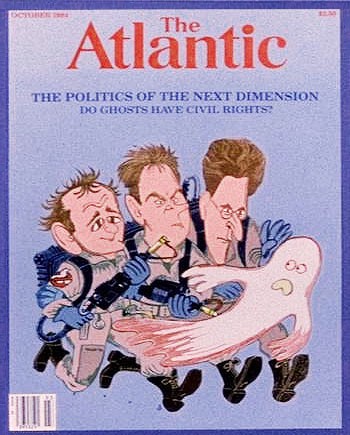

An abridged version of this article first appeared in the October 1984 issue of The Atlantic Monthly as the cover story “The Politics of the Next Dimension: Do Ghosts Have Civil Rights?” It is republished here, in its entirety, for the first time.

For anyone with insomnia in the New York metro area, the ads have become ubiquitous: three middle-aged men dressed in cornflower blue lab coats, holding mysterious technical equipment, and offering the owners of haunted houses (or haunted anything, really) their unique ghost capture and removal services.

I first saw one after falling asleep to the dulcet drawl of Charles Rose on “CBS News Nightwatch.” The spot feels like a parody of those local commercials starring used car salesman and “crazy” warehouse owners. It ends with the team pointing their fingers at the camera, like Uncle Sam in an army recruitment poster, and shouting flatly over the din of passing traffic, “We’re ready to believe you!”

You may know of these men already. They’re the Ghostbusters.

Until the beginning of the current fall semester — when Columbia University abruptly shuttered its psychology department’s program in paranormal studies — Dr. Egon Spengler, Dr. Ray Stantz and Dr. Peter Venkman had been conducting research into extra-sensory perception and recurring manifestations of what they call vaporous apparitions and psychokinetic activity. “Psychics, ghosts, floating stuff, to the lay person. But to us it’s way more technical,” Dr. Venkman explains, half ignoring me as he rifles through the bottom drawer of a filing cabinet, then fixing me with a cold stare. “Stuff floats for a lot of different reasons.”

Our original cover, from October 1984.

“Dr. Spengler and Dr. Stantz are the only people I’ve seen who have taken all these parallel dimensions proposed by Bosonic String Theory and Superstring Theory, and are attempting to correlate them to supernatural events,” says Freeman Dyson, a theoretical physicist and mathematician at Princeton. “They’re the only ones actually gathering hard data on subatomic behavior during these unexplained occurrences — at the Ivy League-level anyway.” Notorious among colleagues for his contrarian streak, Dyson has avidly followed Dr. Stantz and Dr. Spengler’s articles in the journal of London’s Society for Psychical Research. It is outré reading material for a winner of both the prestigious Max Planck medal and the Harvey Prize, but Dyson is effusive in his praise for Stantz and Spengler’s felicitously documented case studies.

“[But] that third name doesn’t sound familiar to me,” he says.

It was Dr. Venkman, in fact, who lead the charge to commodify the trio’s academic research into a for-profit enterprise, talking Stantz into mortgaging his family home to purchase a headquarters for their business in lower Manhattan’s TriBeCa neighborhood. In just a few short months, the Ghostbusters have since rocketed to prominence, following a string of alleged successes in what they call the “reclamation of paranormal phenomena.” Clients, judging from press reports, have included a business at Rockefeller Plaza, a restaurant in Chinatown, the fashionable Manhattan night club The Rose, and their first widely publicized case at the five-star Sedgewick hotel.

Their service began to garner national attention almost immediately after the Sedgewick episode, with features on the Ghostbusters appearing in USA Today, Time magazine and a segment on Larry King’s late-night talk radio show on Mutual Broadcasting. Last month, they serendipitously acquired their own theme song, “Ghostbusters,” a Billboard-charting R&B; single by Ray Parker Jr., whose previous hit “The Other Woman,” coincidentally, also had supernatural elements. Occasionally, when the song is playing, the Ghostbusters will walk with a peculiar strut that looks bound to hyperextend their knees or trip passers-by.

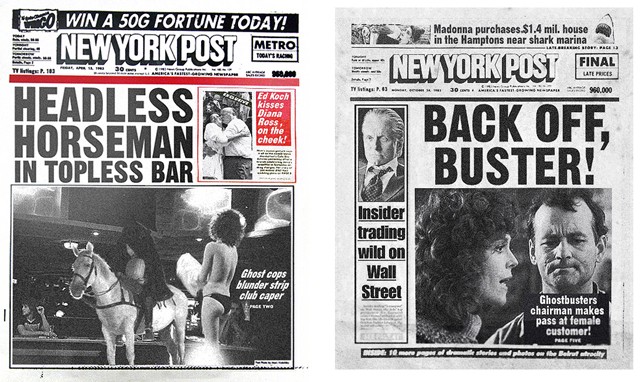

The Ghostbusters’ more infamous appearances in the New York Post. (Credit: Front pages for the October 11th and October 16th, 1984 editions reproduced courtesy of News Corp.)

Lately, this media attention feels like it’s sliding into mass hysteria, having already triggered a spike in ghostly sightings and haunted house cases across the country — and, as an obvious corollary, plenty of business for the Ghostbusters. But locally in New York their fame seems more qualified, occupying a liminal space between hometown heroes and objects of popular ridicule. Nowhere was that ambiguity more on display than earlier this month, when Venkman and Stantz appeared on “Beyond Reality,” a paranormal call-in show on Manhattan’s public access channel J, answering questions live over the phone and from the undead via Ouija board. Venkman, in particular, came off as ready to take the format into prime time. He sparred with crank callers — latter day Harry Houdinis looking to debunk the Ghostbusters’ televised séance — frequently insinuating their employment in various menial, degrading jobs while reminding them that his own labors let them work those jobs in peace.

“Did anyone have a grandmother named Iris?” Venkman asked the audience at one point, while manning the Ouija board with the show’s host. “She says you need to eat something.”

It was hard to tell if Dr. Stantz was being equally glib with me when I brought up this television appearance later. “I think it’s good for us to engage the public on Occult topics, but I recognize it’s an uphill battle,” he said. “Deservedly so, even. There’s every practical reason why Western Civilization has been stigmatizing this kind of esoteric knowledge for millennia: It’s immensely powerful, nasty stuff. Dangerous. Unpredictable.”

Having now pored over several out-of-print books on medieval demonology and mysticism on loan from Dr. Stantz, I’m still unsure how someone with advanced degrees in both psychology and physics could seriously entertain such a baroque spiritual cosmology. America has, of course, a long history in the thrall of pseudo-scientific, quasi-religious movements, from the Spiritualists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries to today’s Scientologists and infomercial televangelists. Are the Ghostbusters merely just the next wave? Or are they simply con-artists capitalizing on the moral panic created by the increasingly influential evangelical Christian movement, with its shrill warnings on the dangers of demonic possession, satanism and the always imminent “end of days”?

For their part, Stantz, Spengler and Venkman all refused to comment for this article on their rather lucrative involvement with both the plaintiffs and the defendants in the McMartin Preschool “satanic ritual abuse” trial. They were also equally silent when I asked them about a National Enquirer piece that claims Ghostbusters International had received payments via White House discretionary funds through First Lady Nancy Reagan and her alleged personal astrologer, Joan Quigley.

“I wouldn’t call them hucksters from my personal experience,” says Dana Barrett, a cellist with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. “I don’t know. It’s just sometimes hard to believe they were former college professors and not just former students.”

Barrett garnered some press attention after The New York Post learned that she had been the spectral reclamation firm’s first customer. (Barrett declined to elaborate on the nature of the supernatural occurrence in her apartment, but her neighbor Louis Tully told the Post that it was possibly a misunderstanding, given that “Dana leaves her television on a lot by mistake and, you know, it makes a lot of funny noises. There’s been complaints, but I don’t mind, personally. Dana’s great.”) The Post had a field day with claims that Dr. Venkman was ostensibly attempting to flaunt his credentials as the chairman of the Ghostbusters, “the largest paranormal investigation and removal company in America,” as a pretext to spending the night with Barrett in her apartment. Barrett has refused to comment on the Post story, but says she has retained the Ghostbusters’ services until her case is resolved.

It’s perhaps no shock given the firm’s ivory tower-pedigree, but coverage of the Ghostbusters in the Post has been remarkably adversarial, beginning with an early exposé on the negative aspects of the Sedgewick hotel incident. The ghost catchers had arrived at the Sedgewick at the climax of a bizarre, two week-long alleged haunting that was costing thousands in room service receipts, according to the hotel’s manager. Multiple patrons, the manager claims, had complained of a goblin-like apparition eating their food. A police report filed without charges by the hotel, but unearthed by the Post, stated that the Ghostbusters had destroyed a chandelier and much of the the Sedgewick’s main ballroom just minutes before it was scheduled to host the Eastside Theater Guild’s annual “Midnight Buffet.” Employees of the firm additionally scorched a stretch of wall down a twelfth floor hallway, according to the report, and nearly killed a member of the hotel’s housekeeping staff, evidently mistaking her sheet-draped cleaning cart for a ghost.

“They left me there trying to put out flaming toilet paper with a bottle of Windex,” said the maid, who asked not to be mentioned by name. “They said they were sorry, but didn’t try to help, at all. [They] nearly killed me! I think they’re assholes, to be blunt with you.”

The Sedgewick reportedly absolved the Ghostbusters of all responsibility for the property damage and the charges of reckless endangerment — as well as paying them a total of $5,000 for what many would consider the dubious service of removing a “focused, non-terminal repeating phantasm or a class 5 full-roaming vapor” (i.e. the food goblin).

Some clients, however, have been less charitable. Ghostbusters International, Inc. is currently listed as the defendant in one civil and two criminal cases in the tri-state area.

The first was a kidnapping charge brought by the descendants of two young women who had been tried for witchcraft in colonial Brookhaven and whose avenging spirits were now purportedly terrorizing teens at a Christian Youth Ministry overnight in Glen Cove, Long Island. The case was thrown out of Nassau County’s Tenth District Court when the victims’ 319-year-old death certificates were produced at a pre-trial hearing by Dr. Spengler, who for financial reasons has been acting as the firm’s legal counsel himself.

“Egon is a real Renaissance man and very dedicated to Ghostsbusting,” says the firm’s executive assistant Janine Melnitz. “And I think that’s very admirable, even though it doesn’t leave him much time for more personal, recreational activities.”

The second case pending against the firm, The State of New Jersey vs. Ghostbusters International, Inc., et. al., concerns a roughly 2,700-acre forest fire that the company is accused of starting in Wharton State Forrest while attempting to capture a legend of local folklore, the Jersey Devil, in the Pine Barrens National Reserve. Their client, prominent naval architect and owner of the New Jersey Devils hockey franchise John McMullen, is also listed as a defendant in the criminal complaint, which is scheduled to go to trial this February.

“My anticipation was that covering this trial would be a return to a region and a people that I’d come to love two decades ago,” says John McPhee who wrote about the arraignment in last month’s issue of The New Yorker. “Instead, it’s turned out to be a whipsaw return to the ghastly moral calculus of nuclear research, which I examined in my book on Theodore Taylor [The Curve of Binding Energy]. These Ghostbusters have essentially been operating cyclotrons — high-powered, particle accelerators — out in public with zero government oversight. Now, we know some of the risk factors here, because proton therapy has been a viable form of cancer treatment for decades, but no one, not even today’s leading lights in quantum mechanics, have practical experience with proton stream behavior at these flowrates.”

After the Glen Cove “witch” incident, McPhee says he spoke to physicists at Brookhaven National Laboratory who voiced concerns about Stantz and Spengler’s “proton pack” ghost catching technology. They likened the accidental intersection of these particle beams to operating a nuclear collider, or an “atom smasher,” out in the open air — multiplying the concerns that already swirl around this kind of high-energy particle collision research. In a telephone interview, Edward Witten of Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study confirmed McPhee’s anxieties saying that the theoretical basis exists for at least two doomsday scenarios: “Case 1. The Ghostbusters could accidentally create a microscopic, but stable, black hole that might begin accreting matter very rapidly, until Earth and its celestial neighbors were swallowed whole; or Case 2. The Ghostbusters could accidentally produce a bound state of quarks called a strangelet, which arguably could lead to a runaway fusion reaction reducing the planet to a large, smoldering orb of strange matter or a quark star. In either case, it would be pretty bad.”

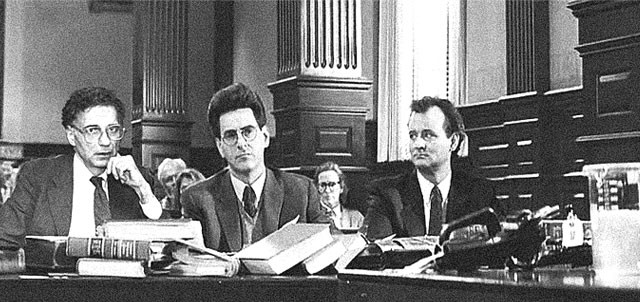

From left to right, consumer rights advocate Ralph Nader and Ghostbusters International co-founders Dr. Egon Spengler and Dr. Peter Venkman at a September 6th, 1984 hearing of the New York State Assembly’s Special Committee on Nuclear Safety. (Credit: Jeremy Ladd for the Albany Times Union)

When I broached this topic with Dr. Spengler, he said that while the Ghostbusters don’t normally discuss their proprietary technology with the press, they can say that SOP training has been implemented internally to mitigate the stream-crossing issue. He cited the firm’s voluntary appearance at the New York State Assembly’s Special Committee on Nuclear Safety in Albany this past September where details emerged of an independent audit on their facilities, conducted by Public Citizen, Ralph Nader’s consumer advocacy group.

“I voted for [Libertarian candidate] Ed Clark in the last presidential election and have had zero interest in voting either before or since,” Dr. Spengler told me as we sampled a chickpea-based Lebanese dish that Nader had left in the Ghostbusters’ office. “So it’s safe to say that Ralph Nader and I do not share much common ground, though I do respect his lack of sentimentality.”

The third and potentially most costly litigation facing the company is a class-action suit being pursued under the Clean Air Act by the Environmental Protection Agency. It began when guests situated above the Sedgewick Hotel’s main ballroom began complaining of a chlorine smell and a pale blue gas. According to the EPA’s lead investigator in the case, Walter Peck, there is considerable evidence from the Sedgewick and several others sites that the Ghostbusters’ spectral removal process generates ozone (O3) — a toxic ingredient in photochemical smog known to cause severe respiratory damage — at levels well above the limits set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Peck says the ozone-levels are of particular concern for clients in well-insulated spaces with low ceilings.

“It’s a ridiculous accusation,” Dr. Stantz says. “Any astrophysicist will tell you that proton streams from solar storms will routinely dissolve parts of the ozone layer. The whole reason our technology works is that these spectral manifestations are comprised of a negatively charged plasma. We are not causing these ozone levels, okay?”

“What Ray’s telling you is true,” Dr. Venkman added. “The ghosts are making the ozone.”

I made sure to broach this issue with Walter Peck in a follow-up interview. I also asked him what he thought was the legality of a private firm detaining someone’s immortal soul — particularly the souls of U.S. citizens as in the Brookhaven witch case — but he refused to entertain either of these ideas even as hypotheticals.

“I’d rather not dignify this confidence game the Ghostbusters call a business plan by openly discussing whether undead ghosts and goblins ought to have due process under the law,” Pecks says. “I don’t for a minute believe in these campfire horror stories, but irregardless [sic] the spectre of above-threshold ozone toxicity is very real. The basic fact is that three discredited academics are now out there, pointing dangerous, high-powered equipment at every creaking door and drafty window in New England. We need regulation and we need oversight.”

“He said that?” Dr. Stantz reacted with shock. “’Irregardless’ isn’t a real word, you know.”

“Frankly, there’s no accepted case law on the undead at the moment,” Dr. Spengler added, “but taking into account the inter-dimensional nature of these entities, I would argue that this is largely an immigration issue or a contraband issue depending on the sentience. Technically, INS should be deporting spirits of the deceased, as well as the other apparitions, the demons. We submitted a contract proposal, actually, but they haven’t responded.”

When this topic arose, I finally summoned the courage to ask the Ghostbusters about their containment unit, which Stantz, Spengler and Venkman led me downstairs to see. The ultimate spooky basement, the bottom floor of the firm’s TriBeCa headquaters is an ever-increasing summation of every other haunted basement in the world. Behind a phalanx of cautionary industrial signage, a red-painted steel casing, and an energy-intensive magnetic field, lies every spook, specter, apparition, ghoul and ghost captured by the Ghostbusters. Again: allegedly. Listening to the unnerving hum of the containment unit, I asked again about the ethical dimensions of corralling these seemingly conscious beings indefinitely within the company’s high-tech purgatory.

“We all feel kinda bad about the Sedgwick slimer,” Stantz told me. “After some of the hauntings we’ve witnessed in the past month, there’s definitely something endearing about a ghost whose only crime is maniacally pigging out.”

“He also smelled like onions,” according to Venkman. “I’m not letting him out of there.”

Few law scholars were willing to speak to me about the hypothetical legal issues of ghost entrapment.

Thomas Shaffer, who taught estate law at Notre Dame for 12 years, suggested I contact the Diocese of Rome’s resident exorcist Gabriele Amorth, but the priest declined an interview. One outspoken champion of Dr. Egon Spengler’s extradition and deportation analogies, however, horror fiction writer Stephen King, says he has spoken to Justice Department lawyers and others who were willing to support Dr. Spengler’s legal arguments.

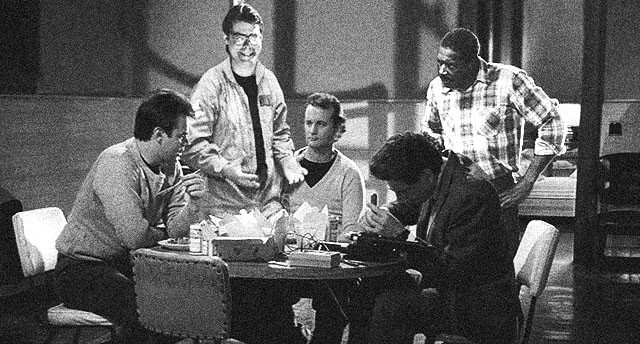

Horror author Stephen King, second from left, in 1985, the year after this article’s initial publication, dons a pair of official “ghost hunting” coveralls while trailing the Ghostbusters team. (Credit: Janine Melnitz, Ghostbusters International, Inc.)

“To a person, they’re all Reagan appointees or generally conservative in their interpretation of the law. One is a Lutheran and an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court,” King said. “But they’ve all told me, off the record, that they could see this ‘inter-dimensional foreigner’ interpretation holding up, if a case were ever to go to trial, which frankly doesn’t seem likely. Personally, I think the argument would especially hold up in the Jersey Devil Pine Barrens incident or with a poltergeist — anything that’s not a former citizen and also possessing someone or causing physical damage is clearly engaged in a criminal act itself.”

King just recently signed a six-figure book deal, his first major foray into nonfiction writing, to chronicle the Ghostbusters’s exploits for Simon & Schuster’s Free Press imprint. Slated for release next September, King’s book, The Dehaunters, is being marketed as the first in a new genre: supernatural true crime.

“I’ve always envied those ride-alongs that crime fiction writers do with local law enforcement,” King told me. “This is my first time doing this kind of intensive procedural research for a book. It’s exciting. I’m still wrapping my head around some of the physics, but it’s been incredibly exciting. There’s something perfect about this business operating out of an old firehouse, with this pole and everything. I think we’ll live to see Ghostbusting as a genuine municipal utility.”

“I think Ray is the only one who’s genuinely happy that King is here all the time,” Spengler confided in me.

“It’s not that he isn’t a nice guy,” Venkman says. “It’s just that he’s way, way too excited. Sometimes, though, it’s nice that Ray has someone to talk about 14th Century Romanian magicians with — and he’s good at playing Star Gazer,” a pinball game on the building’s second floor.

Though King’s will be the first book to market, publishers are clearly banking on an increased demand for anything and everything Ghostbusters. John McPhee says he was contacted by pulp novelist Richard Bachmann, author of The Running Man and the upcoming supernatural thriller Thinner, about co-authoring a competing nonfiction project for the New American Library’s Mentor imprint. Tentatively titled Negative Beings, the book differentiates itself from King’s by focusing on the technical innovations behind the company’s flashy spook hunting.

“Bachmann is a strong science fiction writer and I’m a strong science writer. So, the hope is that we’ll be the first to resolve, for a popular audience, some of these outstanding questions about what the Ghostbusters do,” says McPhee who confided that he has not yet met Bachmann, but has been impressed by his written correspondence. “I can’t seem to get him on the phone, but I can tell Bachmann’s taking this seriously. I don’t want to stoke some literary feud with a top-selling phenomenon like Stephen King, but I think we’ll be making a valuable contribution with this second book.”

McPhee laughed off my questions about the ethics of Ghostbusting. “Who are you going to call? A lawyer?”

Cliches like “legal gray area” fail to adequately describe the terrain the Ghostbusters find themselves navigating, far out on the fringes of quantum physics and spiritual mysticism (ostensibly), and operating technology no one seems to understand. They’re off the charts — either wildly past the point of illegality, inventing new crimes and committing weird combinations of old crimes at a staggering pace, or positioned well beyond mere civic virtue at some superheroic point we may have to call sainthood.

It’s cold comfort given these stakes, but according to Bill Lauren, who is publishing an exclusive on the Ghostbusters’s proton packs for Omni, the team is at least routinely grappling with these thorny moral dilemmas in their downtime, even considering new ethical dimensions their critics have yet to broach: accidentally transporting clients to parallel dimensions, permanently ripping the fabric of space-time, catalyzing something called a “full protonic reversal” that they refuse to elaborate on and that no scientist I’ve spoken to has ever heard of.

“Just sitting in on the casual watercooler banter between them has been enough to give me nightmares,” Lauren confided to me. “You should ask Egon about the current Twinkie-to-Twinkie ratio.”

Around the office the Twinkie ratio has become sort of a gallows humor shorthand for assessing the increasing volume of “psychokinetic” (i.e. ghostly) activity in the New York-area, as compared to static levels. According to Dr. Spengler, the ratio is currently a Twinkie the size of a school bus. And it’s growing. The company is looking to hire and train new personnel to meet demand, but worry that they may have to start making some concessions to their own ideals.

“Up until now, we’ve been reticent to patent our technology simply because most of it has some disconcerting alternative uses,” Dr. Spengler says. “Dr. Stantz and I have already turned down two no-bid contract offers from the Department of Defense for strategic defense initiative research and some kind of death ray. We’ve felt that keeping our hardware proprietary for as long as possible was a great way to avoid regulatory overhead and keep the technology out of the wrong hands. But there’s a limit to the security we can afford to maintain that secrecy. And — especially if the Twinkie keeps getting bigger — we may have to form some sort of partnership with a state or federal bureaucracy.”

“That all being said, we are incredibly patriotic,” Venkman interjects. “Don’t forget to write that down. No one, nobody, loves this country more than the Ghostbusters.”

Oh, geez. Matthew Phelan has previously written things for The Onion, Inside Climate News, and Chemical Engineering magazine. (The cartoons and Photoshops were also by the author, fwiw.)He would like to thank two particle physics researchers, Dr. Peter Yamin at the Brookhaven National Lab and Prof. Sunil Somalwar at Rutgers, for reviewing this piece in advance. Obviously, though, if there is a mistake in the writing up there, somewhere, that isn’t just clearly made-up Ghostbusters stuff, then it is entirely and exclusively Matthew Phelan’s fault. Also, literally all of you should know that Prof. Somalwar helps run a nonprofit called Saving Wild Tigers that wouldn’t say no to donations; nor would the New Jersey chapter of the Sierra Club, where he is vice-treasurer.

Big Windows Will Help Rich People Overlook Historical Taint Of Poverty And Illness

“St. Vincent’s Hospital served the sick and the poor for more than 150 years in the heart of Greenwich Village. Now, condominiums under construction at the site have been selling quickly and at some of the highest average prices ever downtown, developers say.”

Jose Gonzalez, "Stay Alive"

I had put this on in the background and was then doing something else, as is so often the case in our tab-intensive world these days, when I was suddenly caught short by the realization that, hey, that is a very pretty song playing in the background there, you should pay more attention to it. So I did. Turns out it’s by Awl pal Ryan Adams and it is from the new version of Walter Mitty that will come out soon no matter what your worries about it are. Give a listen.

John Legend Speaks For Us All

“John Legend Says What Everyone Was Thinking About David Brooks” is a headline we are reading, here in 2013, because that is the way things are now.