The Twelve Days Of Awlmas

Good morning! And welcome to our 265th annual holiday extravaganza. Here’s how it’ll work. In the mornings we’ll be “resurfacing” (LOL) some delightful things that perhaps you have or haven’t seen before. Then in the late mornings and afternoon, we’ll be presenting new stories that explicate the year that is even now dripping through our fingers as the future speeds towards us like a brakeless truck. So many metaphors in 2013.

From Rihanna to Geraldo to James Deen, from Russia to Gi Joe: Retaliation, from fan fiction to parking spaces, from cats to restraining orders to the terrors of European television to lesbians to SoulCycle, we’ll be looking back at what made 2013 so… special? Terrible? Disturbing? Something.

And then we’ll all emerge on the other side, in the parallel universe of the de Blasio era, where literally anything could happen. How magical. You guys are great, thanks for everything.

The Year In Crying At Your Desk

Enough about how technology is changing us, for now. It’s the end of the calendar year, and we’re consumed with the attendant complicated feelings of the holiday season, as well as settling accounts before the 13 changes to 14. And in that tally of the year soon to lapse, we look back. We remember. We write year-end reviews.

One opportunity that talked-to-death technology has afforded us, in ways that our parents never experienced, is the peculiar phenomenon of surreptitiously consuming Internet content while at one’s place of employment, and then being emotionally moved to the point of perhaps betraying the fact that one is not reviewing a spreadsheet but instead watching a video or scrolling down a listicle.

And not to say that everyone experiences such a thing at the same time or in the same way, but this then is a look back at the year of crying at your desk.

Some people are better at crying at things than other people. I am one of those people. Crying, at Bridge To Bridge To Terabithia or Old Yeller, that’s kids’ stuff. The movie scene that I have most wept at is the final scene of A Christmas Story, the very final scene, when Darren McGavin and Melinda Dillon sit on the couch as the children sleep and look quietly out the picture window as the snow falls in the night. There’s nothing sad about that. It is just a perfect moment of peace and contentment that is the rarest of creatures in the non-movie world, and at that point I am heaving sobs. Because, I’m still waiting.

Any TV commercial that consists of a montage of people being fine, being the finest to each other (like this recent one) is also a trigger for me. There is a genre for ads like that. Let’s call it “sadvertising,” as some have called it, though it’s not a new thing at all, and it’s not really sad! It’s not really sad at all. It’s a vision of some idealized life that you may or may not be lucky enough to experience in real life. It’s a time-worn trope for advertising. The new thing is that we do not watch them on TV but they get memed out in dribs and drabs, and we watch them at our desks, and QED.

This is why I’m bad at watching TV, and this is why I present myself as an authority when it comes to crying at things, at your desk or otherwise.

It is necessary to say that obviously not everyone has a desk, let alone the opportunity to spend what hopefully is lunch or other non-work time to fart around on the Internet during the work day. For that reason, consider desk-crying as a useful shorthand for “consuming digital content that causes one to involuntarily engage in some level of crying while in the presence of others.” Can you desk-cry if you are taking a break while telecommuting from your local café? Of course. Maybe that’s even better, because those other people are freakin’ strangers, and that means maximal awkwardness. Can you desk-cry while working from home? Most likely not, unless there is an actual stranger there with you — a repairman, that cute guy/girl from the bar last night, a burglar. Can you desk-cry from the floor of a tool and die factory? No, not unless you want to get fired and also beaten. But let’s just accept this as a thing that exists, and be happy/sad for those for whom it does not.

Oh, there was a real good one that rolled out around mid-year, I Forgot My Phone. This one was not an advert, but it made the rounds with the appropriate amount of “crying at my desk.” We’re going to label this one as sui generis as it doesn’t really fit into any of the categories described herein, but it is a colossal work, capturing the dark reflection of the Zeitgeist at just the right time. I personally did not cry so hard that I had to turn my head from my desk and fake like I was having an allergy attack, but the dislocation captured in the piece was worth a tear running down the cheek. The power of it is not some obvious tragedy, or tragedy forestalled, but the complicity that comes with the realization that the level of culpability of the viewer will not effect any change in personal behavior with regards to the viewer’s personal hand-held device, and that’s a pretty heavy, existential tearing up. We’re not crying (at our desks) at the sad story or for that poor lady. We’re crying at the innocence lost and the ways the world changes that we’re not only powerless to stop but complicit in. Nice fuckin’ job.

In the course of looking for the desk-crying finest of the past year, I informally polled friends as to the what had them all choked up inappropriately. Many of their suggestions appear herein, but one friend suggested something that needs to be hashed out. “The story from last week about having to have rape insurance in Michigan.” “Oh yes, but that’s not what I mean by crying at your desk,” I replied. “I was at my desk. I cried,” she insisted. And well she should, as it is a brutally inhuman bit of code from one of the dumber laboratories of democracy. This is another distinction I’d like to make — desk-crying and real crying are different things. Crying at the Michigan law, or at the Newton shootings or 9/11 or some other horrible thing, that’s real crying, evinced by a certain amount of personal loss. When you cry because of really cute photos of a toddler and a puppy, you’re essentially crying at some terribly moving thing that has nothing to do with your personal life. That is some desk crying. (And yes, the Michigan law does have something to do with everyone’s life, as it’s yet another exhibit of the world getting shittier.)

Is there a stigma to desk-crying? Well, people judge, so of course there is. There is a stigma to that hat you wear to work. But generally we don’t let this stigma get to us. Think: the plural of stigma is stigmata, and crying is almost exactly like stigmata, but from your eyes, and with salty water instead of blood.

Even though the Internet runs on cats, when it comes to desk crying, dogs are the household pet of choice. Just last week, photos of a boy running into traffic to save a dog ran on Huffington Post. This is an example of a popular subcategory of desk-crying content: dogs in peril. Dogs being rescued from ice flows, from cardboard boxes, from puppy mills, and just plain old dogs being rescued from

being abandoned. (Is there a listicle for that? Yes. There is a listicle for everything, silly.) And even though this is from last year, I’m including this story of a dog being rescued a mile out in the water after its owner was killed in a car crash because, can you believe it?

The unspoken law of the dog-in-peril posts is that the dog must survive. Not that the tears would not flow like wine in stories about dogs not surviving, but that would be a whole different thing. We suppress the tears at our desks not at the unkind fate befalling man’s best friend, but rather at the happy ending.

Of course the ne plus ultra of desk-crying dog videos are the videos of dogs greeting vets returning from service. That collection of videos is just one example. Seemingly, every vet to return in the past twelve years had not only a dog but some sort of video recording device, and they are embroiled in a massive conspiracy to wring every last tear out of desk-crying Americans. And I applaud them for that (and their service, of course).

What is it that’s so wrenching about this? Is it imagining yourself as the vet, forced to be away from family (and dog) for so long? Is it imagining yourself as the dog, whose emotional reaction in each case can only be described as, “HOLY SHIT!! HOLY SHIT!!” Or is it just empathy, a monster dose of pure, un-stepped-on empathy?

Surely there must be some equivalent for cat videos, but as of press time, there is not. The response to diabolical cuteness is not crying, not so much.

This whole piece, this look back at the year in desk-crying, probably would make more sense as a series of animated gifs, or the captioned photos we now call “memes.” That’s the current trend, and there are sites that traffic in that business out there that you can find easily, by checking your Facebook feed, or any other feed, for that matter. These sites have found a way to monetize these bits of so-called “viral” content. That’s neat for them! I wish them the best. There’s nothing I like more while crying at my desk than realizing that someone’s business plan figured that a buck could be made off that.

Not every bit of desk crying content is yanking at your heartstrings with snapshots of the world working correctly. Sometimes, we cry because the content is sad. Very recently you might have seen this photoset, a recently widowed father recreating wedding photos with his young daughter, make the rounds amongst your acquaintances. Ouch.

We can all agree: death is scary! And when beloved figures pass away, be they public figures or not, some pretty moving content gets written. Take for example Laurie Anderson’s account of Lou Reed’s last moments. It’s not even a couple hundred words but it’s beautifully composed, and the story of his passing is so dignified and perfect that it’s hard to make it through on the umpteenth reread.

Last month New York newspaperman Peter Kaplan away suddenly. (Well, not suddenly, but his illness was not common knowledge.) Kaplan was not exactly a public figure, but he was well-known and respected inside the community generally responsible for filing well-composed copy in memory of the departed, so by the first week of December, all kinds of great (and by great, I mean uh-huh uh-huh) stuff coming accross the transom. And while it’s not fair to pick the best, David Carr and Tom Scocca on Kaplan’s funeral are both impossible to get through without a sniffle, and holy cow this one byJim Windoff is good.

Although I will argue that when we are moved by someone writing beautifully about the passing of someone (or even a dog named Duck) else, of course it is a moment of sadness but it’s also a moment of appreciation of the things that we aspire to be.

There are also those posts in which a photographer chronicles a loved one’s losing battle with cancer, which deserve mention as a subcatagory of the sad desk-cries, largely for the fact that they are just not fair. I mean, come on, this is about crying at your desk, not taking the day off for sobbing.

But I’m not being fair, because the most titanic and indelible (and overpopulated) bit of memetic desk-crying content of the year 2013 is, of course, Batkid. It was perhaps the greatest triumph of the Make-A-Wish-Foundation. Five-year-old Miles Scott, battling leukemia, wanted to be Batkid for the day. In planning the event, the Make-A-Wish-Foundation found the San Francisco Police Department and the Mayor’s office to be enthusiastic. The wish granted grew into a full day of Batkid (with Batman), saving San Francisco (and rapper Pitbull) from the Riddler and the Penguin, ultimately receiving the key to the city in front of 20,000 cheering fans, topped off with a supportive Vine from the President of the United States. That is some not-a-dry-eye-in-the-house stuff.

And ubiquitous! This story ran everywhere, all across the globe. There were rumblings of a backlash on the social media, namely on the grounds that it is unfair to single Miles out when there are so many other children with life-threatening illnesses, and I get that. We’ve all had/will have our experiences with this sort of thing, and very few of us get to see our ailing loved ones have an entire city stop to support them. But it’s not fair to resent Batkid, any more that it’s fair that anyone gets the big C. It was the most massive display of compassion I can remember. It was the day we all cried at our desks together.

And I’m certain that I missed your own personal favorite, the one that absolutely wrecked you and you had to pretend that you were sneezing and you buried your face in the kleenex and gritted your teeth until the tears subsided. Sorry about that. There’s just so much out there.

There’s not a single damn thing wrong with desk-crying. It’s uncomfortable and awkward, but I’d rather have a feeling than not. The mechanism of “emotional release” in having a good cry is debated in scientific literature, but you and I know it’s there, in the same way that we know that the need to actually cry, the bereavement kind, dwindles over time. Bad thing happens, and the amount and intensity of the sobbing diminishes over time. Bad thing happens, and you might be staring at a couple days, or a couple weeks, of breaking down. But it gets better.

And in the same way, when you get a good case of desk-crying, you share it. You tweet it, you throw it on Facebook (“I can’t even”), you call over your officemate, and then you feel better. You had feels, but you’ll feel better. There are more feels in your future. But you are not alone. It certainly doesn’t feel like it, but desk-crying is about hope. This is stuff shared by other people, shared with other people. Shared. Fellowship is part of the equation. And however it is in the future (wearable computers with retinal projection maybe?) that we will experience these little blips of socialized heart-swelling, the hitch in your breath that the world can provide such moments, those will be about hope too.

Baby Bears Want To Get The Hell Out Of Houston Just Like Everyone Else

How about we all make our escape now? Don’t let them trick you with the peanut butter and fruit scam, they just want to throw you back in your cage. Roam free, you baby bears. And to all a good night.

Alex Wiley, "Suck It (Revolution)"

There’s the Christmas you dream of and the Christmas you actually get. Here’s hoping yours if the former rather than the latter when next week finally rolls around. This is what mine would look like, minus the having to be in Chicago part. Enjoy. [Via]

The Shape Of Clues To Come: The Crossword At 100

by Ben Tausig

Crossword puzzle from April 25, 1965, found by David Prasad.

The crossword puzzle, which turns one hundred years old this Saturday, is a native New Yorker. Contrary to popular belief, it was not born in the virtuous, cosmopolitan New York Times but in the back pages of the now long-defunct yellow-journalism daily The New York World, among the ads for breast-augmentation serums. In 1913, The World was one of scores of city papers grabbing at readers with sensational and morbid hooks, high-contrast photos of men in hats standing over fresh corpses, headlines about the secret lechers and killers of the grim urban anonymous. These were the crossword’s childhood neighbors. The crossword, originally called the “word-cross,” was adapted by Arthur Wynne, editor of The World’s games and puzzles section, from an as-yet-unstandardized puzzle found in Europe since the late nineteenth century (Wynne himself was British). Wynne did not so much invent as re-present and popularize the feature. There seemed to be no sense at the paper that it might be a hit, until it did. And it may well not have been if it weren’t for Manhattan.

The city was a fertile medium in which to grow, for largely the same reasons that urban areas support crossword solving today — commuters on mass transit need something to do. What better way to ease a weary morning brain into the day than a mildly challenging, twenty-minute word game? You fill it out on the go and then toss the paper in the ashcan outside the office, with a sense of satisfaction at having wrapped up your task completely. According to Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader, “The B&O; Railroad put dictionaries on all of its mainline trains for crossword-crazy commuters.” The subway, still young then, discovered a soul mate. Urban transportation and crosswords grew up together. Soon, most of the city’s newspapers had their own puzzle feature, joined by other metropolitan papers like The Boston Globe, and by 1925, the trend was peaking. New York celebrities, including Governor Al Smith and Will Rogers (who lived and entertained in the city at the time) even wrote their own puzzles, while baseball players and beautiful people were routinely photographed solving them.

But like many New Yorkers who stick around for a few years, the initial thrill soon wore off. When one is neither young nor rich here, but doesn’t yet want to leave, there is usually only one choice: get a steady job. The New York Times, after almost thirty years of openly denigrating the “fad,” got on board in February 1942, just as the United States was entering World War II. It was a victory gimmick, a distraction from all that. The Times puzzle debuted near photographs explaining the differences between various models of biplane. Margaret Farrar, former assistant to Arthur Wynne and probably the most important figure in the history of the crossword, was its first editor. She did away with the irregular rules and grid shapes that other papers had employed, inaugurating the square grid and symmetrical pattern with which we are now familiar. The structural rules she put in place were largely aesthetic, and they created an iconic daily artifact. Farrar edited the puzzle brilliantly until 1969, when she was forced into retirement. It was under her that the crossword became essentially synonymous with The New York Times.

But the ensuing two decades were mediocre, especially at the Times. Will Weng is remembered fondly by some, and subsequent editor Eugene Maleska by vanishingly few. Weng’s puzzles could be inscrutable, but he did at least have a sense of humor. Maleska, who served as a district superintendent of schools in the Bronx, brought an administrator’s gruffness and sober passion for educational basics to bear on his editing. Maleska’s puzzles were high-brow handjobs. Esoteric entries like CINCHONA (“Quinine-supplying tree”) served little purpose except to stroke the egos of those schooled in a particular version of classical European knowledge — geography, botany, theater. Perhaps the crossword was moribund in this period because America had its collective mind elsewhere in the 70s and 80s, or perhaps the pendulum of propriety simply had swung a bit too far.

It was only in the late 80s, with the ascendance of the whiz kids at Games Magazine and elsewhere, that the crossword returned to glory. When Will Shortz left Games and took over at the Times in 1993, he opened the door wide to pop culture and punny humor. The puzzle got funnier and fresher, and the variety of themes expanded greatly. Shortz has had a tremendous effect on both the visibility and quality of crosswords since the early 90s, and his influence remains outsized. He has also hosted the prominent American Crossword Puzzle Tournament, since before he began as editor, helping transform the puzzle world into a tightknit community, and remained ubiquitous in the media. With Shortz, the crossword attained a human warmth in the popular imagination.

There have been highs and lows in the first hundred years. But, from the vantage of the archive, crosswords are transparently much more than a pastime. They are like dictionaries of human awareness. Every clue is a truth about the world on which the constructor and solver must shake hands. In retrospect, those truths are not always nice. In 1926, for example, constructor W.P. Wooten clued the word WOMEN as “They’re uncertain and coy” in the New York Herald Tribune. Crossword clues must pass the so-called substitution test, such that the answer can replace the clue in a sentence and vice-versa. So the word SEE can be substituted for “Watch,” just as in a thesaurus. The fact of women’s uncertainty and coyness was, for a significant percentage of the Herald Tribune’s readership, a given. Fast-forwarding to the Maleska era, it was similarly assumed that an intelligent person would know the name of an Andean medicinal plant genus. The editor and audience sign a tacit contract that the grid can be filled using common knowledge, and so they must agree on what constitutes common knowledge. Close readings of crossword puzzles thus reveal ontological agreements that float around in certain corners of the world at particular times. There are few other endeavors that do this so vividly.

So where does the crossword go next? We are now, decidedly, in the era of indie/digital crosswords. But “The Internet” is an obvious and insufficient answer. Plenty of newspaper puzzles are already playable on apps, and some exciting newer ones are online only. But even these are still frequently printed and enjoyed offline, often along the same subway and elevated train routes where the game first rode to prominence. Amazingly, paper and pen/pencil are still king. Devices provide some new contexts and the opportunity for certain kinds of gimmicks, but Farrar’s rules and the printed page are still vital for the puzzle.

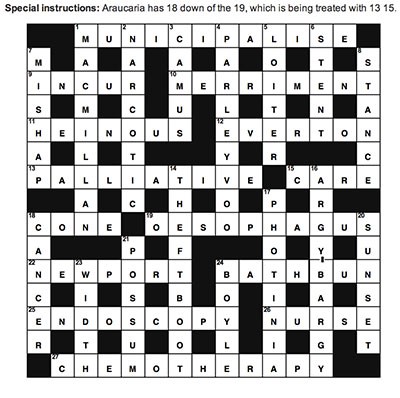

Rev. John Graham’s announcement puzzle.

Constructors and editors might make some progress by embracing what’s unique about crosswords as expressive bearers of shared knowledge. Crosswords in this regard are a peculiar and quite postmodern kind of art — densely packed semantic containers that are utterly, immediately disposable. To say that puzzle makers should think more about their work as an art form is not to suggest that they be more genteel or self-reflexive. Nothing much needs to change about the crossword, including the sense that it’s all in good fun. But there may yet be room for puzzles that leave us feeling ambiguous or bittersweet. A cryptic crossword setter for The Guardian, Rev. John Graham, revealed in a puzzle a year ago that he had inoperable cancer; he published his last puzzle in November, days before his death. Most creative works, from novels to TV to movies to photographs, can and do evoke all manner of emotion. Crosswords have barely dabbled in much other than humor, but they could. The proliferation of critical puzzle blogs where construction is taken seriously, suggest that there may be room for doing so. This is an area I hope to see mined in the coming years, if only as a niche.

Meanwhile, the disposability of crosswords offers a number of possible new angles, with which figures like Peter Gordon, Brendan Emmett Quigley, and Amy Reynaldo and Trip Payne have been leaders in experimenting. Gordon writes puzzles based on events from the previous week, Quigley seeds his grids with of-the-moment entries, and Reynaldo and Payne edit themes that might reference celebrity news stories from as recently as yesterday. This is a scale of freshness that simply isn’t possible with newspaper crossword publication cycles. The best contemporary puzzles weave modern references with knowledge of an older vintage. The temporal scales can, in subtle ways, even address each other, as in a recent American Values Club puzzle “written” by a just-emerged cicada (whose cluing was precisely seventeen years out of date).

Finally, crosswords can still make huge strides in compensation. The existing model sees constructors vastly underpaid given the scarcity and value of their work, and frozen out of the secondary market for reprints almost entirely. This is the case in spite of the fact that puzzles, unlike commentary and journalism, have not been devalued by the ubiquity of free content online. Pay-to-play subscription crosswords have grown up just as print has declined, and there are quite a few profitable ones now. Digital crossword subscriptions make more money than ever for The New York Times, even as the paper seeks ways to make up for declining circulation. Crosswords thus have a chance to be leaders in giving just compensation for intellectual work, bucking an otherwise powerful historical trend. Crossword outlets can elevate themselves by raising pay and including royalty-sharing clauses, becoming a more robust medium by attracting higher-quality work. Not many creative fields have that kind of opportunity today. I have a daydream in which I publish a Marxist-Leninist tract in Forbes about generous pay as late capitalism’s great remaining market inefficiency, with the crossword industry as linchpin.

I’m sanguine about the future of crosswords in their current digitally available but paper-solvable form. What has likely led to yet another puzzle renaissance in the past decade isn’t technology so much as the formal creativity and play with disposability that many of the above-linked puzzles have embraced. The centennial of the crossword’s beginnings prior to LaGuardian ambition, Lindsaian crisis, and Bloombergian technocracy sees it linked but no longer moored to urban places; the world thinks, plays, and moves differently now. I’ll ask you to fill in the rest.

Ben Tausig is editor of the American Values Club xword, and author of the weekly Ink Well feature. His most recent book is called The Curious History of the Crossword. He has a Ph.D. in ethnomusicology, and has studied music and protest in Thailand. He’s written for the Awl, the Hairpin, and others.

How To Stop Being Such An Angry Dick

“Uncontrollable anger could be cured by taking aspirin after scientists found excessive bouts of rage may be the result of an inflammation in the body. Intermittent explosive disorder, which is sometimes known as ‘anger syndrome’ usually begins in late teens and is defined ‘as a failure to resist aggressive impulses.’… However researchers in the US found that people diagnosed with IED had higher markers of inflammation in the blood than those with cooler heads and average tempers.”

A Poem By Thomas Devaney

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

The War Vase

None of the words in my voice

are my own. What I can see

I see only through your eyes:

the tempera gold leaf — my vessel,

my vim.

The accumulation

of all my reflections; your face

is older now too. Still, I am rash —

a prize above the fray.

Spared

in the minds

of those who will not spare

each other.

Emanation is a light

that can shine

from one’s own body.

But ruder powers do the job

I cannot do myself.

My only enemies are those

who will not fight for me.

Thomas Devaney is the author of The Picture that Remains (The Print Center, Philadelphia, 2014). He is the editor of ONandOnScreen and he teaches at Haverford College.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Your Waking Brain Is Just As Stupid As Your Sleeping Brain

“If you can’t help snapping at your other half, blame your dreams. A study found that the content of our dreams spills over into our real-life relationships, triggering rows and doubts in the day to come. The idea that our waking life influences our dreams has been much studied. But the latest research looks at whether what we think about when asleep affects how we act when we wake up.”

Donna Summer, "Love To Love You Baby (Giorgio Moroder Feat. Chris Cox Remix)"

I don’t know how your family does it, but nothing says Christmas to me like this song, so it’s a thrilling accompaniment to the season to have this remix to extend the festivities. [Via]

Screwed Up

“An earlier version of this article misstated the name of a movie Mr. Goldstein starred in. It is ‘Al Goldstein & Ron Jeremy Are Screwed,’ not ‘Al Goldstein & Ron Jeremy Get Screwed.’”