Cornelius, "Sometime/Someplace"

All this and rain.

Weren’t we just here? Wasn’t it moments ago that we were waking up to a new week, full of dread and barely able to drag ourselves to the starting line? Didn’t we just complain about how exhausted we were and wonder how much more we could take? I guess the good news is I can copy and paste this exact block of text over and over again until it finally all comes down, because we live in a world where it’s always like this now. Here’s some music. Enjoy.

New York City, July 6, 2017

★★★ The radar on the weather app made it look as if the gray outside was raining, which seemed like more meaning and purpose than its blandness could live up to. The pavement was wet, or sort of wet, and there was something between the sky and the ground, but it was all too weak to think of as rain. A glimpse of cloud-dimmed sun flashed by in a puddle. The smell of wet paint hung in the mouth of the subway stairs. By afternoon the halfhearted showers had given up and the day was turning back into the usual. Enough cloud stuck around to form strange shreds and brilliant monochrome patterns on the way toward sunset.

Lambchop, "The Hustle Unlimited"

What you may have missed while everything fell apart.

Unfortunately the early November release of Lampchop’s FLOTUS — one of the best albums of the band’s incredible career — was somewhat overshadowed by the full horror of our American nightmare coming to fruition, but now that we have had enough time to adjust ourselves to the destruction of the republic and the inevitable violation of whatever made it great I am hoping everyone will take some time to revisit this masterpiece. To whet your appetite here is a disco revision of “The Hustle.”

And, as a bonus, their cover of Prince’s “When You Were Mine.”

Enjoy.

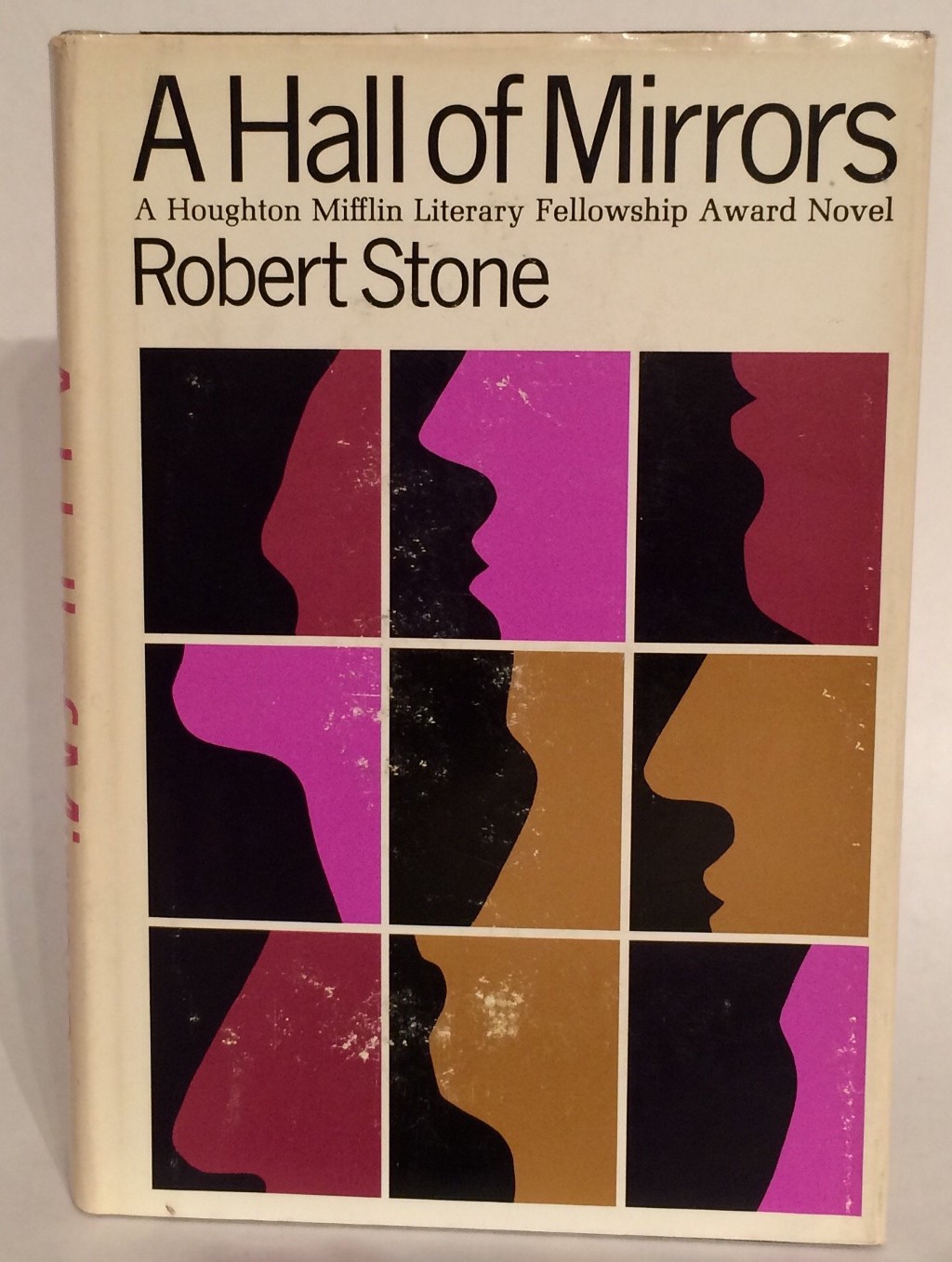

Dial It Back to 1967

Re-reading Robert Stone’s ‘A Hall of Mirrors’

About a quarter of the way through Robert Stone’s 1967 novel A Hall of Mirrors, the cool, sardonic main character, Rheinhardt, arrives at the New Orleans headquarters of soon-to-launch radio station WUSA — The Voice of an American’s America. He’s asked to tape a “real swinging” news spot to “turn people on to what’s happening,” and when he delivers, he’s called into the office of founder Matthew J. Bingamon. After releasing Rheinhardt’s hand from his grip, Bingamon tells him:

“When I listened to that spot I was able to see a picture. A part of a pattern. If I had listened to any other five minute straight news broadcast on any other station it would have been obscured, wouldn’t it? But because you see it, you made me see it.”

“The pattern,” Rheinhardt said. “Yes.”

“Well the news, so called, is a very important part of what we’re trying to do with WUSA. Because there is a pattern. But it’s hard, Rheinhardt, it’s very hard to get across. Every honest man in this country feels it — and not only in the South — but everywhere in the country. They feel it, they pick up a trace of it here and there. But there are people whose business it is to keep that pattern obscured. From our point of view these people are the enemy.”

Anticipating the rise of right-wing radio, Fox News, “fake news” — and its violent trajectory — half a century ago, A Hall of Mirrors reverberates beyond any account of American politics you might read in 2017. Stone’s writing is wry, poetic, even hallucinogenic. Focused on outsiders in a hustle-or-be-hustled atmosphere where social and racial tensions are about to explode, it’s rich with colorful con artists, pot-fueled thinkers and scarred, tender souls seeking a home in the world. And though the worst parts of its early-’60s setting don’t need a revival, the book’s attunement to forces on the scale of religion and myth can make our present-day culture feel cosmically bereft. Up ahead: the Restoration Rally.

Karen Hudes previously wrote about literary agent Candida Donadio, who represented Robert Stone, Thomas Pynchon and Joseph Heller, for Tin House. She has contributed to The Hairpin.

Guster's Ambivalent Nostalgia

Where it’s always balmy summer or a gently crisp fall.

Over the course of my tenure as a Guster fan, I attended only one of their concerts. They performed at my alma mater, the College of William and Mary, on Homecoming weekend the fall after I graduated. That’s a fitting context for a Guster show if ever there was one: inside a gasp of collegiate nostalgia, where I was both haunted and seduced by my past selves. At the time this felt like comfortable pseudo-regression. I wasn’t ready to be somebody else yet.

Thankfully, Guster doesn’t write the sort of songs that demand assertiveness or resolution — though they do often articulate that aspiration. Guster, I learned when I discovered them in high school, invites us to dwell in queasy uncertainty, the variety that accompanies our most capacious experiences: alienation, deceit, love, time’s passing. And they’re always looking back, though their vantage point is vague, a roving dot that elides firm position. There are bands we return to because their sound lassos old memories that, at the time, were fledging moments. That’s one way to indulge in nostalgia and, of course, Guster summons this effect like any other musical relic from the past. But they also trade in the experience of nostalgia — its thick, heady atmosphere: their music revels in it, turns it over, and examines its contours. Guster invites us to tarry in nostalgia for its own sake.

There’s something peculiar about this, because the band’s music has always struck me as fundamentally atemporal. It’s a matter of form and affect more than particularities of content. Inside of a Guster song, it’s always balmy summer or a gently crisp fall, unless — in the case of “Rainy Day” — foul weather is the point. Technology is generally unremarked upon, save for in the broadest strokes — a stray reference to MTV or a track entitled “Airport Song.” Instead, lovers write letters to bridge distance or meander through the May parade, quietly mulling over their soured romance. And while we can pinpoint Guster’s heyday as the stretch between the late nineties and early aughts, the band has never fit comfortably within a genre, unless of course you acknowledge their ubiquity within college a cappella circles.

Yet Guster’s soul is fixed, at least geographically. They were founded by Adam Gardner, Ryan Miller, and Brian Rosenworcel at Tufts University, taking shape in early ’90s New England with an intimate but devoted following. In 2003, multi-instrumentalist Joe Pisapia joined the fold, but departed seven years later in 2010 (Luke Reynolds took his place). With the exception of some colonial flair, Boston and Williamsburg, Virginia share precious little in common. Nonetheless, I felt — or fantasized — a kinship with Guster because I craved a world that was as vivid and earnest and picturesque as their songs. That is how I both envisioned college and how I remember it now.

Guster’s shtick could seem hokey — misty watercolor memories, and all that — and their sound overly precious, but neither was the case. Their Garfunkel-esque harmonies retain raw edges, and when necessary, the robustness of their percussion signifies emotional urgency. There’s pain inherent to both hope and reminiscence, Guster reminds us. Ideals are spun from disappointment and sorrow, whether we’re gambling on the future or aching to recall a time better than the present.

This is to say, what is most poetic about Guster is their ambivalence. “Come Downstairs and Say Hello,” a slow-swelling wallop from their 2003 album Keep It Together articulates the solicitude beneath defiant claims of change. “To tell you the truth, I’ve said it before / Tomorrow I start in a new direction,” Ryan Miller intones, “One last time these words from me/ I’m never saying them again.” Both the rhythm and Miller’s voice gradually grow more confident — “I look straight at what’s coming ahead / and soon it’s going to change in a new direction,” he declares — but as the melody waxes we’re carried away not by surety but by the desperate hope of wearing it as a mask. And yet, when it comes to Guster, neurosis rarely registers as jagged or dissonant. On the contrary, “Come Downstairs and Say Hello” features some of the band’s sweetest, most transporting harmonies. The yearning in Miller’s vocals and eagerness in the percussion burgeon, but maintain a steady cadence. This seems to be the point — that anxiety is threaded into our lives so intimately we can scarcely detect its origins. We’re always sliding around on a continuum of fear; we manage how we can.

“Come Downstairs and Say Hello” strikes me as one half of a pairing: the latter, more mature half. Its earlier and perhaps more self-indulgent variation is “Two Points for Honesty,” the penultimate track on 1999’s Lost & Gone Forever. There’s less subtlety here, in lyric as well as in melody — and instead of timid hope, pessimism wins the day. Again, Guster’s speaker contemplates the future with potent longing, but this time is swallowed by self-defeat. No welcoming voice issues an invitation to “come downstairs and say hello,” no one reassures, “don’t be shy.” Instead, as the dulcimer shivers, the speaker arraigns himself via projection. “It must make you sad to know that nobody cares at all,” Miller warbles, in mellow self-condemnation.

In the case of “Two Points for Honesty,” Guster’s juxtaposition of choirboy melody and bitter self-interrogation — generally held in delicate balance — slumps heavily with nihilism. It’s the perfect song for wallowing, which is why I loved it in high school and perhaps, to my chagrin, why it can’t supply me with the same pleasure now. In adolescence, there is an insolent comfort to proclaiming oneself alienated, or even a lost cause of sorts. After all, the former is often the case, at least to some extent — admitting that can be a relief. As teenagers, we’re the cruelest we’ll ever be, to ourselves and to each other. In that raw time, we’re sometimes more comforted by what feels true, whatever the empirical data. And we’re always vulnerable to the terror Guster acknowledges: we want something better, and we’re sure it doesn’t exist.

What Guster understands, and what they’ve always articulated so exquisitely, is that we’re perpetually yearning both backwards and forwards. When, at 15, I heard “Either Way” for the first time, its delicate melancholy elicited an ache for loss I hadn’t yet endured and couldn’t possibility understand. Yet it was just as easy to contemplate the decade and a half that had already passed. After all, from the time we are young we learn to dwell in memories; it’s a consequence of thinking. Guster welcomes us wherever we are, invoking tender, if bittersweet, reflection upon all that we have ever felt, or will feel.

At the end of their William and Mary Homecoming show, Guster asked the crowd to participate in an experiment. Rather than depart the stage, in anticipation of an encore, the band asked us to turn away and stand with our backs facing them. On the count of three, we complied en masse, and for a few moments, our bodies pulsed with swollen silence. I was impatient and uncomfortable, but I had felt that way all day.

“This is fucking weird,” Miller said.

We turned and assumed our previous positions on the grass. I’m not certain that they played “Homecoming King” next, but I prefer to remember it that way.

What Are We Looking For In Amelia Earhart?

Behind the myth making and heroine worship.

“Did I tell you I have a reputation for brains?” — Amelia Earhart, 1917

There are few more enduring celebrity chameleons than Amelia Earhart. She was a very public androgyne, although she cannily femmed up for publicity photos. She married late, included with Charlotte Brontë as anecdata in Rebecca Traister’s All the Single Ladies. She broke countless aviation records and fought and campaigned to bring women into aviation and other fields. She also taps into our shared public imagination for pithy rejoinders, contrarians, appealing “cool girl” tomboys, and missing white women. Really, Earhart notches into the tiny center of a complex Venn diagram whose other potential occupants I can’t think of. Dorothy Parker plus Marie Curie? Ruth Bader Ginsburg in a khaki coverall?

But these sanitized net positives make up only the skeleton of a legend. Earhart is not a résumé skills list or a greatest hits compilation. She was a privileged upper-class woman who orchestrated her own image with precision. In a sense beautifully pinpointed by Jessa Crispin in her book I Am Not a Feminist, Earhart was empowered by capitalism in the form of her own wealth, implied belonging, and the support work of other women. She was able to buy an airplane, period. She married for career advancement and material comfort. She lied about her age out of common human vanity. None of this tarnishes her legacy as a pioneer and boundary breaker, but it adds context to our sixth-grade-book-report understanding of her.

Earhart attended school somewhat sporadically and never earned a college degree, but she served on more committees and student governments than Election’s Tracy Flick. In her letters you can tell how enthralled she was by the power of these offices and how easily she dismissed other opinions. Her confidence and assurance were staggering, a fact that repeated throughout her life — scolding her mother repeatedly for writing letters to Amelia’s school about her daughter’s well being; sharing news of a crash as though reassurance meant there could be no further questions about it. When she stayed at the White House under President Herbert Hoover, she missed most of the opportunities to dine with the First Family due to her own schedule, as though the President were a convenient AirBnb host while she lectured in town. Her brazenness is bewitching at a remove, as are the mythical accomplishments of a demigod.

Rebecca Solnit’s excellent essay for Literary Hub, “The Loneliness of Donald Trump,” resonated as I thought about Amelia Earhart. Earhart’s accomplishments put her in a very small class, and her savvy self-promotion and endless touring severed many of the remaining links. Her contribution to the lives of her mother and sister took the form of mailed financial support and gifts with naggy, condescending caveats. Don’t spend this money on the children. Don’t wear this dress without “decent accessories.” When her father, long divorced from her mother, lay dying and palliated by morphine, Earhart faked telegrams to him from her mother and sister. She wrote to her mother that she’d also paid his “hundred little debts.”

The same woman who was both the first woman passenger and the first woman pilot on transatlantic flights told her mother, “Perhaps you’d better not talk my intimate details of salary and business with [sister Muriel]. I don’t want her to spread the news and always fear she will.” There’s no contradiction here. Earhart confronted the daily realities of her finances, her family, and her groundbreaking and courageous career, because she existed and was not authored. Who do we serve when we rasterize her into a flat shape and size we find palatable? Why does someone we admire need to be enigmatic in only the ways we find tasteful and appealing? Even her androgynous flight costumes were fashionable.

In fact, Earhart’s awareness of her image and her tireless work to support it, with the help of the publicist she finally agreed to marry on his sixth proposal, is part of what allowed her to succeed. The public noticed Earhart’s clothing and manner in the same way we still scrutinize women from Hillary Clinton to the fictional competitors on “UnREAL.” Examining Earhart from this perspective can illuminate how shrewd and self-aware Earhart was — how far ahead of her time — and also take us to task for how little has really changed. Earhart was a booster and cooperator with women of all stripes (as long as those stripes were white and middle class, of course). She helped to start professional organizations and lectured almost without ceasing to groups of college students and adults, focusing on the interest of women in aviation. As her contemporary Virginia Woolf empowered college women to seek “to earn money and have a room of your own, […] to live in the presence of reality, an invigorating life,” Earhart used her influence and savvy to enlarge the building women occupied and to continue to purchase land around it. She sought to raise all women up, which included herself.

It’s interesting to wonder how feminist Earhart would have been in a time or place where a recordbreaking woman pilot didn’t first need to fight to be a woman pilot at all. Her ambition and knack for publicity obscure her more complex inner life, and she was too busy or otherwise unwilling to share these private thoughts in her letters. But she was politically progressive and campaigned for the reelection of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, including ordering her mother not to speak publicly against or even neutrally toward the President. Certainly it would disappoint her that nearly a full century after she began her aviation career, only about one pilot in twenty is a woman.

But Earhart’s handling of the press and careful tending of her image was unquestionably modern. I’ve seen her expression in photographs described as a “winning smile,” but it’s more of a Mona Lisa quasi-smirk, probably because she was self-conscious about her teeth. In 1936, she arranged a trip to Europe for her mother but again sought to control the scene: “In all cases be careful of reporters. They may find you out. Be cheerful with them and smile for photographs. The serious face in real life looks sour in print. The grinning face moderately pleasant.” Earhart tended to her mother and sister as though she were their mother instead, even their pageant mom. Dress this way, smile, don’t make me look bad.

Earhart’s attempted around-the-world flight marked a turning point, in that she wanted publicity rather than to also break a record or explore new territory. Her employer, Purdue University, sponsored her airplane and wrote it off as a “flying laboratory.” There were skips and starts, including a failed first attempt, and it was during this time that famed inventor and navigator Philip Van Horn Weems wrote to Earhart offering to train her in cutting-edge navigation and radio operation. His letter is carefully written — Earhart, he says, is an unquestionably able and talented pilot but would join a class “almost by yourself” with specialized navigation and radio training. She could save resources and worry in the long run. He appealed to her ambition to be the best and to always learn new things. He offered the training for free.

To me, this is the only real “what if?” moment in the enduring mystery of Earhart’s disappearance. Flights had used Morse code for nearly ten years by the time Earhart planned her trip, but neither she nor Noonan learned it. By the 1930s, Morse code was de rigueur, and location codes were broadcast from navigational beacons all over the world. How did Earhart and Noonan approach a flight whose support was based on Morse code without mentioning that they had no plans to learn or use it? The myth of Icarus reads very differently if Icarus denies that the sun is warm. When their trip began to melt down, Earhart and Noonan had no other option than to fly circles over the area where they believed they should be until they likely ran out of fuel and crashed. The same Navy that fruitlessly tried to guide the flight now used cutting-edge technology in the form of aircraft carriers to search an unprecedented breadth of ocean.

If Earhart herself fell into the space shared by many forms of zeitgeist, her disappearance hits just as many of the key qualities of intrigue. Humankind has still barely explored the very top of the oceans, let alone what lies beneath. At the same time, we don’t feel it makes sense that anyone can disappear into the ocean forever. Is our ability to search really so poor? (Yes.) Can there really be no sign at all of an entire airplane? (Yes.) How can we find closure when a global celebrity simply vanishes? A disappearance alone can make a celebrity. So it’s no surprise that Amelia Earhart reemerges in popular culture all the time. There are documentaries and biopics galore, including 2009’s insipid, lifeless version which Slate’s Dana Stevens called “decorous, conventional, sanitized, dull.” The Star Trek franchise’s most far-out series literally and otherwise, Voyager, places Earhart and a very boozy Noonan on a distant planet where a group of earthlings are held in stasis along with Earhart’s airplane. The episode is even called “The 37s,” in parallel to Earhart’s professional organization The 99s.

But these depictions are Xeroxes with the contrast turned down in order to blend into Earhart’s power as a symbol. The most high-fidelity reproduction of Amelia Earhart’s spirit and entire real personality is pilot Maggie O’Connell from Northern Exposure, who lampshades the resemblance when she says Earhart is her hero. O’Connell comes from a wealthy family where she’s been trained as an ’80s pink-mohair debutante. Earhart’s father was in trains; O’Connell’s is in automobiles. The application of feminist themes to unmarried life and professional piloting changed very little between the 1930s and the 1990s. O’Connell must defend the independence she cherishes, and she judges those around her who can’t or don’t take responsibility for themselves. She even has a stylish short haircut.

Amelia Earhart is often described as charismatic, and maybe that’s the secret to the many other qualities that are overlooked. She was compelling and persuasive on behalf of herself and the many women she inspired, with an unmatched energy level and knack for publicity. Learning about the real woman underneath the glossy symbolism can only help us to understand and relate to her — someone who fought for her career against astronomical odds, but who still argued with her mother well into adulthood about how to spend money or what to do on vacation. Understanding that our heroes have flaws and personalities does not give them feet of clay.

Caroline Delbert is a writer and book editor who wants to know what you’ve found on Wikipedia recently.

Atomic Moms

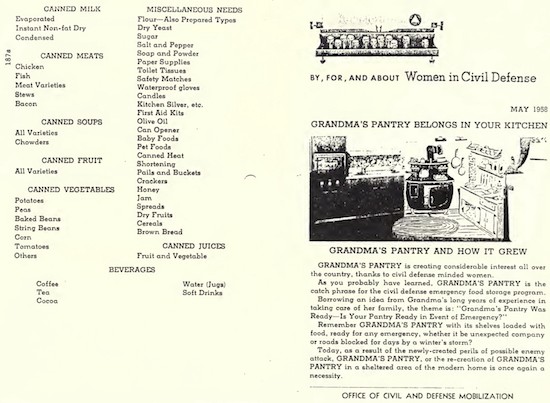

Civil defense lessons for 1950s housewives

Do you feel prepared to withstand a nuclear attack? If not, and if you’re a Baby Boomer, your mother may be to blame. In the aftermath of World War II, the Federal Civil Defense Administration (F.C.D.A.) spent much of the 1950s and early 1960s teaching DIY survivalist techniques to American housewives. Perky spokeswomen toured the country delivering speeches on how to sequester frozen food, recognize air raid signals, and turn A-bomb drills into family fun.

“A mother must calm the fears of her child,” F.C.D.A. director of women’s activities Jean Wood Fuller instructed in a November 1954 address in Augusta, Georgia. “Make a game out of it: Playing civil defense.” Tapped to the post by President Eisenhower, Fuller’s job was ostensibly running civil defense P.R. campaigns aimed at white, upper middle-class housewives. Her projects — a variety of F.C.D.A. leaflets, radio spots, and TV and film programs — and speaking appearances attempted to reassure American women that surviving a nuclear blast was a maternal duty, entailing a manageable set of household chores. “Is Your “Pantry” Ready in Event of Emergency?” asks the widely distributed F.C.D.A. brochure titled Grandma’s Pantry. As historian Elaine Tyler May, Ph.D., argues in Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era, these programs sought to reinforce conservative values and gender roles by instilling a sense of political purpose into mundane domestic life.

Fuller, the second woman to hold the post under the Eisenhower administration, also drew inspiration from her experience at ground zero of Operation Cue, a nuclear test in the Nevada desert on May 5, 1955. “Twenty-nine of us huddled at the bottom of a trench this morning less than two miles from ground zero,” she recounted cheerily in the Los Angeles Times. The operation, Fuller said, “shows conclusively that women can stand the shock and strain of an atomic explosion just as well as men,” and that “with the proper precautions, entire communities can survive an atomic bombing.”

In the May 5 test, a mock-suburban enclave in the Yucca Flats served as the guinea pig. Aptly nicknamed “Survival Town,” the neighborhood consisted of 10 houses in a range of architectural styles. Some of the houses built at the Nevada Test Site featured basement fallout shelters or reinforced concrete shelters in bathrooms. Among various objectives identified in the Cue report, the F.C.D.A. hoped to identify structural weak points and vulnerable building materials. Other areas of interest included how power lines, transformers and radio towers fared the blast, and radiation levels of perishables stored below ground and stocked in kitchen pantries, freezers, and shelters.

Readying the test site for the explosion, civil defense officials outfitted each of the homes with furniture, appliances, canned goods, and mannequins supplied by private industry. Dressed sharply for their doomsday debut, the dolls were perched in living rooms and hoisted into shelters. A less fortunate mannequin family stood upright in the desert fully exposed to the blast, posed as unwitting civilians taking off for a picnic.

The government had been nuking the area since early 1951, but Operation Cue was novel insofar as it sought to address the domestic side of nuclear fallout. In the 1955 F.C.D.A.-distributed short film chronicling the test, Operation Cue is seen through the eyes of “Joan Collin” — an actress posing as a wide-eyed female reporter. Periodically, an unnamed male co-narrator chimes in to answer Collin’s questions or weigh in on technical matters of electricity, power, and weaponry.

“I was especially interested in the food test program,” Collin’s sunny, placid voice explains. “Canned and packaged foods are to be tested. As a housewife and mother, this appealed to me.”

Making her way through the desert landscape, her account of Operation Cue is cheery, inquisitive, and occasionally surreal.

“Interior home furnishings, donated by industry, are complete in every detail,” Collin observes with breathless admiration. “I look at the mannequin sitting about so indifferently…”

In-between polite questions, she marvels at the expertise of civil defense personnel and admires the skillful planning of the operation. Survival, it seems, is simply a matter of following directions and taking proper care of things.

Officials returned to the blast site the day after the explosion for a meal. Carefully planned by the F.C.D.A., the menu included coffee, baked beans, and sirloin roasted over a charcoal fire, suggesting that American everyday life and its comfort foods could prevail in face of nuclear devastation.

According to anthropologist Joseph Masco, some of the decapitated mannequins were even flown out to hospitals by an emergency rescue group in order to practice evacuation techniques. Masco’s report, published 2008 in the journal Cultural Anthropology, argues that visual images of nuclear ruins played a fundamental role in the formation of the post-World War II national security state. These images, Masco writes, further “created a new citizen-state relationship mediated by nuclear fear.”

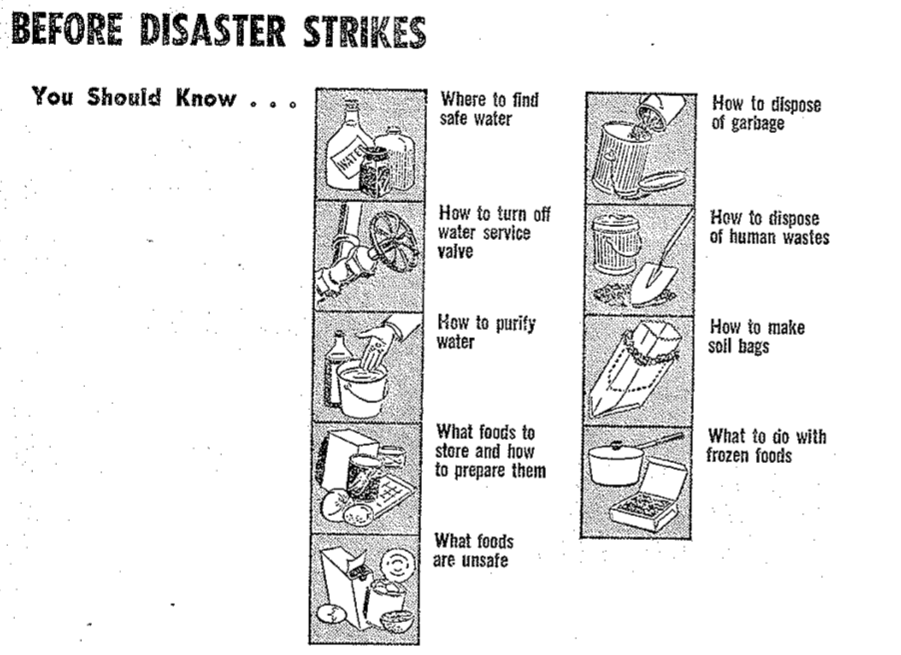

“Everyone in civil defense was trying to project confidence that a nuclear attack could be survived,” historian Laura McEnaney, Ph.D., the author of Civil Defense Begins at Home: Militarization Meets Everyday Life in the Fifties, told me over email. “Mothers had to set the tone for families — to educate children, in particular, about what they should do. Their games and drills were little different than fire drills in schools.” Cutesy propaganda like Grandma’s Pantry harkened back to idyllic, simpler days while tapping into free-floating anxiety about communist infiltration, modern warfare, and other perceived threats to social order.

Though Fuller’s work on the widespread “Grandma’s Pantry” campaign significantly amplified F.C.D.A. outreach to housewives and mothers, many of the program’s fundamental principles were established by her predecessor, Katherine Graham Howard.

Howard had spearheaded similar efforts as the Eisenhower administration’s liaison to women’s groups and the general public. She broke down women’s roles in nuclear warfare into four tasks: learning about different forms of warfare (biological, chemical, nuclear), teaching the rest of the household, keeping the kids calm, and preparing a bomb shelter. An adequately prepared shelter would contain nonperishables, water, sanitary supplies, as well as toys and games to entertain the children.

As noted by McEnaney and other scholars, it is impossible to pin down exactly how many women volunteered during this period — agency records fail to differentiate volunteers by gender. “With the lack of adequate reporting, the best figures suggest about four million people participated formally as volunteers in local civil defense programs across the country,” she told PBS. “More Americans probably read and paid attention to the information, stocked a few supplies here and there, had the air raid shelter instruction card taped to the inside of their kitchen cabinet. But it’s very hard to give specifics on numbers of participants.”

Surveys also noted a disparity between public support of shelter programs and how many people actually built them or considered doing so. In a 1960 Gallup poll, 71 percent of respondents said they would support a law requiring communities to build public bomb shelters, but only 11 percent of respondents said they had personally taken any steps to prepare for a nuclear blast; furthermore, 61 percent of survey participants said they would not pay $500 for a family shelter. A 1961 national survey conducted by researchers from the University of Michigan found that only 6 out of 1,474 respondents — 0.4 percent of the sample — had constructed fallout shelters.

In the process of turning bored housewives into self-fashioned civil defense activists, the F.C.D.A. also galvanized a substantial — and ultimately more enduring — oppositional movement. In November 1961, approximately 50,000 women in 60 cities across the country left their pantries and took to the streets calling for an end to the nuclear arms race. The movement, Women Strike for Peace (W.S.P.), “baffled both the press and the politicians,” writes activist and scholar Amy Swerdlow, herself a W.S.P. participant. W.S.P. called for an end to the nuclear arms race and rejected characterizations of domestic female identity expressed in civil defense literature. Instead, the strikers linked maternal identity with peace activism. The November strike came together using women’s networks, with D.C. organizers spreading word through local P.T.A.s, the League of Women Voters, established peace groups, and religious organizations, as well as word of mouth, Swerdlowe recounts.

The women earned praise on both sites of the iron curtain; Jackie Kennedy and Nina Khrushchev both penned letters to lead organizer Dagmar Wilson offering their support, reports the New York Times. “As mothers, we cannot help but be concerned about the health and welfare of our husbands and children,” Kennedy wrote. In Homeward Bound, May attributes Kennedy’s rhetoric with encouraging white middle class participation in the peace movement and other activism in the early 1960s.

A 1970 issue of Science reports, “[Science Advisor Jerome Wiesner] gave the major credit for moving President Kennedy toward the limited test ban treaty of 1963 not to arms controllers inside the government but to the Women’s Strike for Peace and to SANE and Linus Pauling.”

Called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1962, WSP leaders emphasized the mission as distinctly fueled by maternal concerns. “The movement was inspired and motivated by mothers’ love for children,” Blanche Posner, a New York W.S.P. volunteer office manager, told the HUAC. “When they were putting their breakfast on the table, they saw not only the Wheaties milk, but they also saw strontium 90 and iodine 131… They feared for health and life of their children.”

Fallout fever didn’t entirely die down, but the focus of civil defense programs shifted towards public shelters during the Kennedy years. Kennedy also restructured the civil defense program in 1961, allocating shelter projects to the Department of Defense and incidentally cutting formal ties between F.C.D.A. officials and the network of women’s clubs and organizations. Coupled with the proliferation of anti-nuclear movements, Kennedy’s pursuit of détente after the Cuban missile crisis tempered much of the public fixation on doomsday planning.

The urge to prep never fully went away. A 1992 Washington Post Magazine exposé uncovered a West Virginia fallout shelter built underneath the Greenbrier luxury resort designed to house members of Congress.

“I never mentioned it to anybody,” former House Speaker Tip O’Neill (D-Mass.) told the Post. “But every time I went down to the Greenbrier — and I went there half a dozen times — I always used to look at the hill and say, ‘Well, that’s where we’re supposed to live in the event something happens, and that’s where we’re going to do business, maybe under the tennis courts.’”

In a January report, Buzzfeed News documented a Trump-era revival of doomsday “prepping” among Bay Area yuppies and other people intent on enduring such catastrophes. “We’re still living in the shadow of the Cold War,” said May. “I think we’re living even more in the shadow of the nuclear age, with the saber rattling of the Trump administration.”

The quaint theatrics of Operation Cue and Fuller’s Home Protection Exercises are just that. A 1964 revision of the footage of Operation Cue prefaced the film of the 1955 atomic test with a caveat characterizing the 30-kiloton bomb as primitive and meager compared to weapons developed since.

It would be nice if our mothers could save us, as would be nice if the worst-case scenario meant spending a few days eating spam and playing chess, then going on with things. These are good fairy tales to swap idly and make for cheerier games than counting how many of our weapons would obliterate us and in what order.

New York City, July 5, 2017

★★★★ The sun cut severely between the leaves and twigs, making gentle dappling below. It cast the end-on shadows of sign lettering and the precise silhouette of a security camera. The breeze was easeful. New bare scaffolding and crosswalk stripes and the silver paint on the top of a fireplug all glowed. A pigeon with a white clerical collar bobbed along beside a table of onions in the greenmarket. The tomatoes were still from the greenhouse. On its long way down the sun raised the grain of the sidewalk. The subway platform was hot and stale after the freshness of the cross street. A woman fanned herself with newsprint on a train filling up with the reek of the passengers’ bodies and with the reek of the things applied to the bodies. Up on the surface, the lilies in bloom made the Broadway median smell like a florist’s.