Cats + Tea = Paradise

by Jeva Lange

“Courtney Hatt and David Braginsky, a cat-loving duo from San Francisco, are currently at work on KitTea, a cat cafe concept they hope to open in the city this summer. They envision KitTea as part ‘gourmet tea house,’ part ‘cat and human oasis.’ To ensure the place is not too crowded or chaotic, the cafe will be at least 1,600 square feet, housing a maximum of 10 cats and 30 to 35 people at a time.”

— The excuse you needed to finally move to San Francisco is everything in that paragraph.

Philip Seymour Hoffman, 1967-2014

“Philip Seymour Hoffman, perhaps the most ambitious and widely admired American actor of his generation, who gave three-dimensional nuance to a wide range of sidekicks, villains and leading men on screen and embraced some of the theater’s most burdensome roles on Broadway, died on Sunday at an apartment in Greenwich Village he was renting as an office. He was 46.”

Do You Remember The Before-Times Without Snow

A very lucky Setsubun to you and yours, and the Times points us on this snowy morning to the city’s hilarious snow-shoveling laws, which include an exemption from shoveling snow if it is all frozen terribly hard, in which case you may cause your sidewalk to be “strewed with ashes, sand, sawdust.” But more importantly:

Q: Do I have to clear the whole sidewalk? My sidewalk is very wide!

A: No. You have to clear a path just “wide enough for pedestrians and to allow for wheelchair and stroller access,” the city’s Law Department said.

Q: Can I shovel snow into the street?

A: Please don’t. It can impede the street-clearing process, which is against the law.

Yes. Stop shoveling snow INTO THE STREET, ninnies. (In the rest of America, you are allowed to shovel it however you like, no one cares, just not here in communist New York City.) Also punishable by up to nine months in Rikers is the use of an umbrella during snow.

Pete Seeger's Death Inspires Brief Fantasies About Participating In Social Change

Moments after hearing about the death of 94-year-old singer and activist Pete Seeger, June Atley, 39, sat on her Chapel Hill, NC porch reminiscing about growing up with 70s-era union rep parents. Pete Seeger — whose five-string banjo twanged out the backdrops to the civil rights, social justice and labor movement — provided the family soundtrack. “I remember sitting in the back of our Volvo station wagon belting out ‘Bring ’Em Home’ and ‘Wimoweh,’” Atley says. “Pete Seeger was a hero to me, and I’m going to start living in a way that respects that.” Atley works in software marketing, but she’s going to cut back her hours so she can start volunteering at a local animal shelter. “I know that would make Pete proud,” she said.

In the tony Los Angeles neighborhood of Hancock Park, 52-year-old plastic surgeon Jake Reardon watched as a lawn sprinkler made its way, in a twinkling arc, from the rose bushes surrounding his stoop to the citrus trees edging his curb. “When I heard Pete died, I realized that if I don’t start living my life in a way that respects my values, it’s not a life worth living.”

Reardon was on his way to trade his BMW X5 for a bicycle. Then he was going to ride to the hospital where he worked to inform the powers that be that from now on, he was only doing pro bono work on burn victims.

“Pete didn’t do anything halfway,” said Reardon, who had just posted his favorite song, ‘We Shall Overcome,’ on Facebook. “And from now on, I’m not going to either.”

Across the street, Karen Palmer, 42, waved at her neighbor and came out into the street to chat. “I’ve been listening to ‘If I Had a Hammer: Songs of Hope and Struggle’ on vinyl all morning,” she said. She had an architect coming over in an hour afternoon to draw up plans to turn her 3900-square-foot California Tudor into a homeless shelter. “There’s only so many times you can hear ‘Which Side Are You On?’ without thinking ‘Do we really need this much space?’”

Atley was the first to report that her plans had changed.

“Turns out I’m allergic to cats,” she said, reached at her home this morning. So the animal shelter was out. She considered volunteering at a literacy program, but their introductory meetings were on Sunday nights, a no-go zone. “Have you seen ‘True Detective’? It’s like, can’t-wait-for-the-DVR good. Also, my team has been working so hard on the rollout of this amazing video hosting software, and we’re really a family at this point. And there’s nothing more important than family.”

Palmer had also hit a stumbling block. “Zoning laws,” she said. “The architect said we might have been able to work around them, but in the meantime, my daughter was like, ‘I am not sharing a bathroom with my brother,’ which is totally fair. Also, last night, I had a dream where Pete Seeger came to me and reminded me how rare California Tudors are. And you know, I get it. Pete would not have wanted to just rip this place up.”

Palmer said she started to realize the changes might not be as simple as they seemed when, on Wednesday, she went across the street to check out Jake Reardon’s new bicycle and saw that his X5 was still sitting in the driveway. The Reardons had decided to replace their landscaping with drought-resistant plants, and they realized they were going to need the BMW to transport materials from the garden store.

“I totally respect their decision,” Palmer said, adding that her neighbor hadn’t informed the hospital about any changes in his practice. “Jake felt that Pete would have found that the gesture, without the bicycle, lacked a certain poetry, and I think that’s right on the money.”

Not long after, Reardon called to report that his wife, Marina, had bought the most beautiful pincushion cactus to go in their garden. “It’s flowering, and we’re going to plant it in Pete’s honor and have a little ceremony. I just feel so grateful to be able to pay tribute to him. What an inspiration.”

Atley, who met the Reardons on the Facebook Forum “Pete Seeger’s Death Woke Me Up,” plans on flying to California for the cactus-planting ceremony. She acknowledged that yes, a lot of life-changing plans had been dreamed up and abandoned in a short space of time, but maybe that was okay.

“I think the important thing is that we’re all listening to more Pete Seeger,” she said. “Walking around. In the car. Dancing. I never used to dance before. And now I’m dancing. Yeah, I know Pete spent 94 years fighting systemic oppression, and that’s so, so amazing. But in the end, I think I know what Pete really wanted. He wanted me to dance.”

Sarah Miller is the author of Inside the Mind of Gideon Rayburn and The Other Girl. She lives in Nevada City, CA. Follow her on Twitter @sarahlovescali.Photo by Subbotina Anna via Shutterstock.

What Time Is the Super Bowl... ON THE MOON?

We all know what time the Super Bowl starts, whether it’s here in New York City or in other, less important places, but there’s one question nobody has asked: what time does the Super Bowl start… on the moon? The answer will shock and surprise you! And also confuse you!

The answer: 46–11–27 ∇ 10:43:09, according to the helpful site Lunarclock. Haha look at those weird numbers and that triangle thing in the middle! What!

So: lunar time is much more complicated than Earth time. The moon is “tidally locked” to the Earth, meaning from our vantage point down here, we only ever see the same face. That means that its rotation, lamely, is also locked to ours (think for yourself, moon), and so to complete a rotation, it has to complete an entire revolution around the Earth. Imagine a tennis ball on a string, which you swing around yourself, while standing next to a fixed object like a car (the moon is the ball, you are the Earth, and the car is the sun.). The tennis ball isn’t rotating on its axis, but by the time you’ve spun it allllll the way around yourself, it has technically presented all 360 degrees of itself to that car, thus completing a rotation by the shittiest, technicality-laden means ever.

Okay, so, a day on the moon is equivalent to one complete circuit on the moon’s orbit around the Earth. Let’s leave the sun alone now. When you’re standing at a fixed place on Earth, the moon has completed a complete circuit when it looks the same twice — like, say, the time between a new moon and the next new moon. And the time between one new moon to the next new moon is: one month! So, a day on the moon equals a month (technically 27 days, 7 hours and 43.2 minutes) in Earth-time. Phew!

Lunarclock.org had to make up an Earth-time-like time zone (which is called Lunar Standard Time, or LST) for the moon, because nobody else had, because why would they? It’s based on Earth time: there are 12 “days” in a lunar year, because, remember, a day is the same as a month. Each “day” has 30 “cycles” of time, which would theoretically represent Earth-days, except they don’t actually have any connection to any real passage of time on the moon but are instead an arbitrary division of time to be more like Earth. Each “cycle” has 24 moon-hours, each moon-hour has 60 moon-minutes, each moon-minute has 60 moon-seconds. A moon-second is very slightly shorter than an Earth-second for reasons having to do with the moon’s orbit’s inconsistency and general pigheadedness.

Back to that weird number and triangle! Starting from the left: 46–11–27 refers to the year, the month, and the day. How do you measure years, you may ask? Year 1, day 1, “cycle” 1, etc etc etc, is the moment Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon. As good a time as any, right?

The triangle thing just means “moon-time,” I guess. And the last three numbers, 10:43:09, are simple: hours, minutes, seconds. So there you go! This year’s Super Bowl will air on the moon on the 27th day of the 11th month of the 46th year, sort of, and at just after 10:43 in the morning, also sort of!

Photo by Jamie in Bytown

Albums Return

This somehow blew by me when it was announced back in 2013 (Remember last year? You might not, seeing as 2014 has somehow lasted for the span of three winters so far) but this Tuesday sees the reissue of two of the most unlikely albums to be released by a major label at the end of the ’80s. You should buy them.

Madden Mangled

These Broncos were stone-cold stupid. Madden’s Awareness rating, as demonstrated by previous installments of this series, is one of the very most potent skill categories. Without it, normally competent players are reduced to total knuckleheads who often don’t know what they’re doing, what they’re supposed to be doing, where the ball is, or whether they’re playing a sport at all.

The Broncos’ kick returner, Big Walrus, was so completely checked out that I was able to kick the ball and hit him in the ass.

That was not an isolated incident. There were lots and lots of kickoffs in this game, naturally, since I was scoring all the time. When I kicked them the ball, they kinda just stood there. AND THE BALL KEPT HITTING THEM IN THEIR ASSES.”

— So goes the final installation of Jon Bois’s beautiful “Breaking Madden” project, in which he tries to mangle the settings of Madden NFL 25 in order to make the game freak out and shame the sport of football. Also, the GIFs are world-class.

It's Friday, Drink Rye

I’m glad other people are writing about rye, because it is a delicious and inexpensive liquor and a welcome change from the cloying-if-you-drink-as-much-of-it-as-you’d-like-to bourbon, but most collections of cocktails miss the best rye-based cocktail of them all. Here it is:

INGREDIENTS

– a glass

– one or more ice cubes

– seltzer

– rye

– squeeze of lemon (optional)

DIRECTIONS

1. Combine all ingredients besides the glass in the glass.

2. Nope that’s it, you’re done now.

Photo by Swanksalot

Inside Balochistan With Willem Marx

by Noah Davis

Signed copies of Balochistan at a Crossroads, by Willem Marx and Marc Wattrelot, are available directly from the authors via Paypal. You can get plain old unsigned ones via Amazon in the U.S.

“I was supposed to fly to Afghanistan today but my body armor didn’t arrive in time,” was something Willem Marx said to me one of the first times we met. He says things like this on a not infrequent basis. Marx currently works at Bloomberg TV and has reported from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uzbekistan, the Arctic Circle, and other less trodden parts of the world.

In 2009, he spent time in Pakistan, where he met French photographer Marc Wattrelot. “Balochistan at a Crossroads” is the result of a collaboration between the pair, an unusual coffee table book that focuses on a province in the country whose people are locked in a slow, long-simmering fight for freedom. “It’s a travelogue with some history and reportage,” said Marx, who is donating the publisher’s check to Unicef in the region to help with the efforts to eradicate Polio. “Hopefully, it will give you a sense of a place that realistically, very few of the readers will ever get to visit in the near future.” Body armor optional. We had some questions for him.

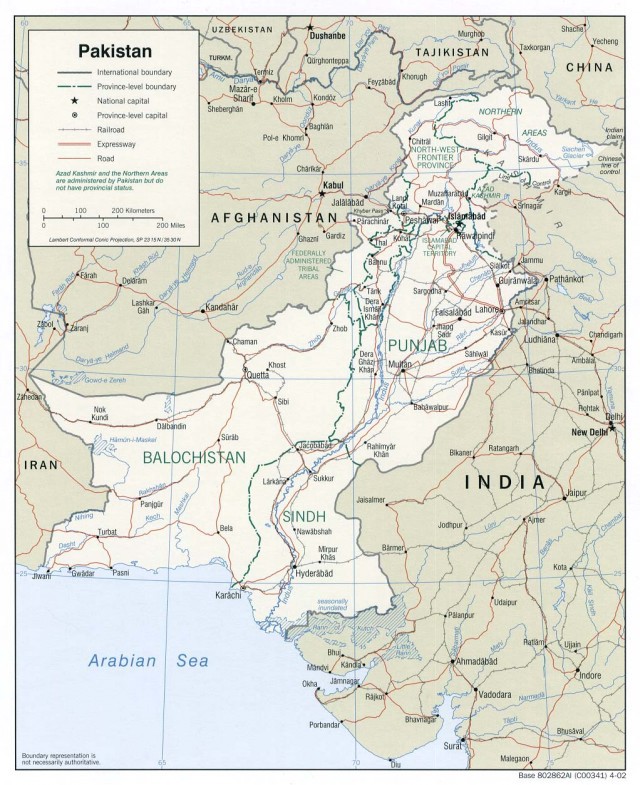

Where the heck is this place?

It’s an area that’s divided up between Pakistan and Iran. You have a province in Pakistan called Balochistan and you have a province in Iran called Sistan-va-Baluchestan. The people from the region are called the Baloch, hence the name of the area. They are a bit like the Kurds in the sense that they were carved up by imperial powers. Consequently, they’ve never really been able to establish their own national identity. If you asked the Baloch in Pakistan, they will say they were an independent state before the British arrived, the British recognized their sovereignty, and then after partition they were tricked by the Pakistanis into becoming part of Pakistan.

So the British are the good guys?

I wouldn’t say that. I would say that in this mythical view that many people have, the Baluch got screwed by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan.

How did you end up there?

I lived in Karachi as a kid, which is just outside the province of Balochistan, but I had never really paid any attention to this name I had seen a bunch of times — until 2005. There was a tribal conflict that was flaring up there. I had just graduated college and was in Baghdad. I read this fascinating BBC News story online about how these people were fighting against the Pakistani army with very little in terms of support and very little in terms of artillery.

CIA map of “major ethnic groups” of Pakistan from 1980.

Does everyone in Pakistan know about this conflict?

It’s like the hidden secret. I cannot get a single person to sell this book. It’s quite bizarre. It’s not because the booksellers don’t want to sell it. They are worried that they will have their premises investigated. No wholesaler will import it. It’s really extraordinary. It’s a secret conflict that’s been going on since the 1940s, the latest iteration since 2005. That’s eight years of low-intensity conflict, but you hear very little about it. Maybe there’s something in the Pakistani press, but it’s very difficult as a journalist to get to the region.

I had gone there as a TV journalist and shot some stories there, but I had so much material that wasn’t used in the packages I put together. Marc had hundreds of photographs, and we thought we should do something because it’s so hard to get there.

Do you have any sense of whether they can break away?

They’d love to but I don’t think they are sufficiently well organized and funded. Their template is Bangladesh. At the end of British rule of the subcontinent, Pakistan became two separate nations. Pakistan was split into two very distinct geographical areas, into east and west. East Pakistan was dominated by ethnic Bengalis who won freedom in the early 1970s. That became the nation of Bangladesh. A lot of Baloch will say we want the same kind of thing. But Pakistan is very sensitive of this because it was very humiliating internationally when it lost a large part of its country and population. They were different and so separated. The Baloch are ethnically different to the Punjabis, the Pathans, and the Sindhis. The nationalist Baloch are very hostile to the Punjabis, who have tended to be the elite since partition, but they do have a big contiguous border, so it would be a little more complicated deciding how to demarcate things. I think that unless they get international support, it’s not going to happen anytime soon.

Did you feel in danger when you were traveling there?

It’s a pretty wild place. There’s a lot of banditry. Being a foreigner makes you a bit of a target. The biggest problem is the Pakistani military. Civilian rule doesn’t count for a great deal outside of the provincial capital, Quetta. The soldiers and the intelligence officers tend to be in charge when it comes to security.

Conversely, when I spent time with the militants who are fighting against them, I always felt that they looked after me incredibly well. They obviously wanted the publicity, so it was in their interest to make sure that I was looked after and safe. But it really felt like going back in time. You have these mountain camps where the rebels live in these very austere environments. It’s incredibly hot during the summer and incredibly cold during the winter. They have a degree of local support so they were able to access food and fuel supplies in the villages. There were entire areas that I traveled to in the province that were under their control. The military had pulled back and left entire valley and mountainous areas up to the rebel.

CIA political map of Pakistan from 2002.

What’s the most scared you were?

I went to meet an Iranian Baloch leader on the Pakistani border. The Baloch in Iran are a Sunni population in a majority Shite country, so they are treated both as an ethnic and a religious minority. If you ask the Iranian Baloch, they will say they are trampled upon repeatedly and they are treated as second-class citizens in their own province. I went to visit this militant who the Iranians considered their most wanted terrorist at the time and repeatedly claimed that he was being funded by the Americans, specifically the CIA. He was a very charming, engaging young guy. We were both around 24 or 25.

Going to meet him was really, really scary. I wasn’t allowed to bring my own translator. I wasn’t allowed to bring the guy who had been driving me around the province. I had to take on faith that these guys weren’t going to do any harm. Their ideology leaned pretty heavily Islamist. The Iranians said they were like al-Qaeda. There were certainly videos of them beheading captives like the Iranian Revolutionary Guard and the Iranian border police. I had to get in a car with a bunch of these guys and hope they weren’t going to do any harm.

Spending time with them on the Iranian boarder was really scary. They were constantly being hunted by the Iranian authorities. It was unclear to me whether I was in Iran or Pakistan at the time. The idea of being in Iran, illegally, without a visa, as a journalist, with a bunch of people who they considered terrorists was pretty unnerving. I tried to limit my time spent with them.

There’s been a lot of talk about the difficulty of freelancing as a foreign correspondent. You were doing this piece for Dan Rather Reports, but it was your first story for them and you weren’t on staff. That’s not a whole lot of security.

In hindsight, I probably wouldn’t pursue this story without better guarantees. Subsequently, having worked at places like CBS that have a great deal more resources and support and training…. Essentially, I had no idea what I was doing. I knew how to film. I knew how to put a story together. But if things had gone wrong, it was me in the middle of nowhere on a satellite phone calling people in New York who themselves had no idea where I was. Getting into a car with a bunch of young, Iranian Baloch militants and saying goodbye to the driver and translator who were the only two people I knew within 1,000 miles was a pretty stupid thing to do. But it ended up making me into someone who the TV show in particular wanted to keep around. I worked for them for several years. But in hindsight — I don’t want to say it was a stupid thing to do, but certainly a risky thing to do.

I’ve thought about that a lot in the subsequent years. It’s one of the difficult things in this line of work. To get attention as a young person, you have to almost go and do stories that other people don’t want to do and put yourself in harm’s way. Now, at age 31, I would a) ask for a lot more money and b) want to know that there were better safeguards. For me, this was a fascinating story and an incredible place to be able to visit and the opportunity was the one that I seized but in hindsight, very risky.

How did you prepare for the trip to Balochistan? You’re basically just parachuting into a place and trying to figure it out quickly.

Well, I was never going to fit in even though I did grow a pathetic attempt at a beard. That said, I spent what was essentially a month reading everything I could get my hands on and speaking to as many people as possible. If every story I ever did could be one in which I could do that, I would be very happy. I was very well prepared in terms of my background knowledge. I didn’t know what to expect physically when I arrived there but I knew what was going on.

That’s one of the amazing things about our generation’s access to information. You can turn up in a place completely alien to you, but because of the Internet you can have read hundreds of thousands of local news accounts that give you a sense of what’s going on there. If you went back to a previous generation of foreign correspondents, that wasn’t possible. You could make as many phone calls as you wanted but it wouldn’t give you quite as much depth and context as you now have access to.

It’s like we’ve traded individual institutional knowledge for a collective knowledge or something like that.

Yeah, and since then, it’s changed even more. Using things like Twitter and Facebook, I could have set up half my interviews in advance. Instead, I relied a network of underground activists. I managed to get permission to travel around Balochistan by explaining that I wanted to do economic reporting in this very economically marginalized province. At the time, President Zardari was talking a big game about what he was able to do about economic improvement in the Balochistan province. Somewhere, I think that struck a chord and they thought it was a good idea. I had the name Dan Rather behind me, and Pakistani press officials knew who he was. So that helped. I don’t think they suspected I’d be doing stories about the Baloch Liberation Army. That might be more difficult now.