What Was Money?

What Was Money?

What was money?

A medium of exchange; a system by which tokens were assigned value by a central authority for use within a regulated system of commerce.

What was money for?

Acquiring things that you needed to live or believed you needed to be happy.

What happened to money?

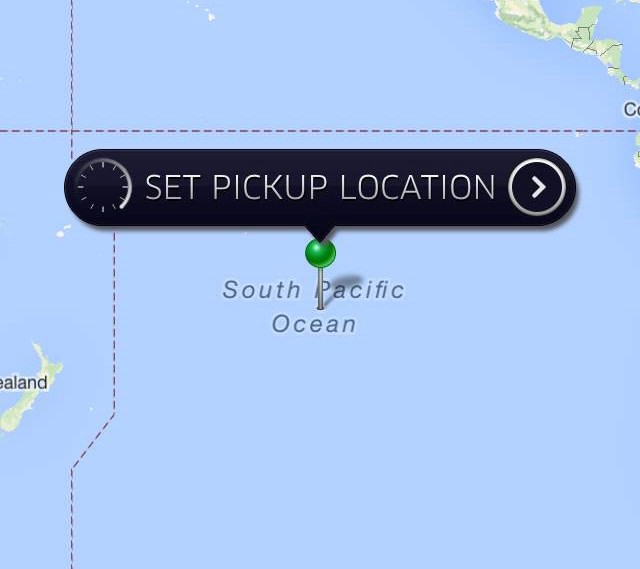

“Uber Technologies Inc. is seeking to join the $10 billion-plus club. The San Francisco-based startup, which makes a mobile application for car-service booking, is in talks to raise new financing in a round that may value it at more than $10 billion, according to people with knowledge of the situation. That would almost triple the company’s value from $3.5 billion last year when it garnered $258 million.”

What happened after that?

The Money Transcendence.

What was the Money Transcendence?

[SILENCE]

Why have I never heard of this before?

[THE GROUND BEGINS TO SHAKE. ALL THE ELECTRONICS IN THE ROOM LIGHT UP WITH VAGUE ALERTS AND THEN ABRUPTLY SHUT DOWN. A SOUND, AT FIRST DESCRIBABLE AS “LOW” BUT SOON SO OVERWHELMINGLY LOUD AS TO BECOME PITCHLESS, EMANATES FROM STREET LEVEL.]

What’s happening?

[BLACKNESS. VOID. ROAR.]

Oh no. Oh no. Oh no.

[A SINGLE RECTANGLE OF LIGHT ACROSS THE ROOM. A SCREEN. A PHONE.]

No no no no no.

A TEXT: YOUR UBER IS ARRIVING NOW.

But I didn’t orde —

[SILENCE]

[SILENCE]

[SILENCE]

[SILENCE]

HOW WOULD YOU RATE YOUR RIDE?

★★★★★

THANK YOU.

New York City, May 14, 2014

★★★ A pavement saw screamed and threw gray dust, as water sprayed from its loose hose connections. The gray sky above was getting brighter, with blue and white patterns fading in. The air carried a refreshing degree of dampness. Full sunshine took over; a pigeon and its tidy pigeon-streamlined shadow waddled by. As the sun continued, the humidity lost its refreshing qualities. By evening the gray was back. A drizzle descended, clinging to the building tops. It glowed in the lights of clogged East Side traffic, snarled by presidential proximity.

The Internet Highway Metaphor Is Dated But Let's Stick With It Anyway

“While the plan is meant to prevent data from being knowingly slowed by Internet providers, it would allow content providers to pay for a guaranteed fast lane of service. Some opponents of the plan argue that allowing some content to be sent along a fast lane would essentially discriminate against content not sent along that lane.” Under the FCC’s proposed new rules for internet service providers, data sent via the non-fast lane isn’t slower, it’s just less fast.

A Design Experiment Inspired by Spike Jonze's 'Her'

by Awl Sponsors

Her is a love story, first and foremost. It inspired a wide community of designers in surprising ways.

Motherboard, in association with Microsoft and Warner Bros., hosted private screenings of the film followed by a 2-day design workshop, asking one question: How can human emotions inspire new interactions with technology and each other?

Captivated by Her takes a fresh look at what’s possible. This two-part documentary follows a community of international artists, designers, and innovators as take part in a workshop exploring how basic human emotion and interaction can inspire new technology.

Check out the what went down during the LA workshop in the video above.

The Song That Made The Pill OK

by Casey N. Cep

Loretta Lynn wrote and recorded “The Pill” in 1972. Her label didn’t release it until 1975, but three years wasn’t long enough to cool the controversy stoked by Lynn, one of the biggest names in country music, singing the praises of oral contraception to an audience of “unliberated, work-worn American females.” The Associated Press’s lede about the song in February of that year read, “To some, Loretta Lynn’s new song ‘The Pill’ might be too bitter to swallow. But to the country music star it has the sweet taste of success,” selling some 25,000 copies a day. The New York Times even gave it a few column inches under the headline “Unbuckling The Bible Belt.”

Despite the coy coverage, Lynn’s song is anything but bashful. Not once, but seven times a wife delights in reminding her husband that she’s “got the pill.” Angry that he’s running around town while “all [she’s] seen of this old world is a bed and a doctor bill,” she announces that her birth control is evening the score. “I’m tired of all your crowing how you and your hens play,” the wife says, and then threatens that she’s headed out on the town, too.

By Lynn’s own account, she married at age 13 and had four children before she turned 18; by the time she released the song, she’d had two more. “I’ve had six kids and I’ll take the pill anytime,” Lynn told the Associated Press in 1975, and then made light of her own naïveté about pregnancy: “I didn’t know at first what was causin’ all this.” A little stage play of sorts, almost as delightful as the song itself, unfolded during the interview:

“I went to the doctor the first time and he said, ‘You’re pregnant.’

I said, ‘What’s that?’

He said, ‘You’re gonna have a baby.’

I said, ‘I can’t have no baby!’

He said, ‘You’re married, aren’t you? Sleeping with your husband aren’t you?’

I said, ‘Yes and yes.’

He said, ‘Well then you’re gonna have a baby.’

“I tell you,” Lynn says, “if they’d had the pill a little earlier, I think I’d have eaten ’em like popcorn.” If she seems cavalier in the interview, she seems even more so in the song. “I’m tearing down your brooder house,” the wife jokes, announcing “this chicken” is taking control of her own eggs. The “incubator is overused,” but, with the pill, “roosting time” is becoming a time for play, perhaps even with other roosters.

The song was banned on some country stations, but that failed to keep it from spreading. The pill was already popular, but Lynn’s lyrics seemed to laugh at the worst fears of those who opposed it: weakening families (even though the wife in the song already has several children) and breaking homes (even though the husband in the song is already sleeping around). The comedy, of course, is that the wife singing is actually pleading with her husband to stop cheating on her; the pill might, in fact, save the couple from divorce.

People Magazine found a preacher in West Liberty, Kentucky, who devoted a sermon to denouncing Lynn and counted at least 60 stations that refused to play the song. Also denouncing Lynn was W.R. Morris, author of “The Country Sound” column that appeared an Alabama newspaper, The Times Daily. “Controversial Song Makes Money For Artist Despite Ban By Stations” was the title of Morris’s column for February 16, 1975.

“Personally,” Morris wrote, “I feel that the song is poorly written and done in poor taste.” Morris was even more critical in his claim that “if an unknown female artist had cut the song, no radio station in the country would have played it. But since Loretta Lynn recorded it, some stations will spin it.”

This is, of course, not true. The song would have gotten play no matter who wrote or recorded it, but because Lynn, a Grand Ole Opry star and the only woman to be named Entertainer of the Year by the Country Music Association, did both, women not only listened to the lyrics, but followed her advice. Her songs, about alcoholism and adultery, heartache and honky tonks, standing up to your husband and the women he was cheating with, coming from nothing and having it all, made her, according to People Magazine,the “poet laureate of blue-collar women.”

So while W.R. Morris of Alabama thought that “Loretta should let the welfare workers tell folks about the pill while she concentrates on recording some good, clean country music songs,” part of the trouble was that those workers had been talking about the pill for 15 years already, but not all women felt it was safe or socially acceptable. The Catholic Church had taken a moral stance against it, and the United States Senate had only a few years before held hearings on its medical safety.

That a folk hero like Lynn, whose life and career were devoted simultaneously to women’s independence and the importance of family, would not only admit to taking the pill, but craft her admission into a cutting attack on a cheating spouse meant that many women, especially rural women, considered oral contraception an option for the first time. You could, the song argued, have children, love your husband, and oppose adultery, all while still taking the pill.

A song like “The Pill” would still raise eyebrows today, not because the pill isn’t taken daily by millions of women, but because it says candidly what so many women are expected not to acknowledge, much less advertise. I cannot imagine what it was like to hear the song for the first time in 1975. I can’t say I’ve ever heard it on the radio, but I remember the first time I ever heard it. It was 2002, and Tim McGraw had just released the first single from his new album, “Red Rag Top” a story of young love like so many others on country radio, except for the turn one minute in, when McGraw sings: “Well the very first time her mother met me, her green-eyed girl was a mother to be for two weeks” and then a few beats later, “We were young and wild, we decided not to have a child.”

I remember catching my breath when McGraw confesses, “We did what we did and we tried to forget and we swore up and down there would be no regrets.” It was, I’m sure, the first time I had heard anything about abortion in a country song; it was also, I’m fairly certain, the first time I’d heard such an honest, non-health-textbook account of the experience anywhere in pop culture.

I was taken by the song, and when I asked my mother if she’d heard it and what if anything she’d made of it and whether she thought country music was becoming more progressive or more honest or anything like it. She listened to all my excited questions, told me Tim McGraw had nothing on Loretta Lynn, and then played me “The Pill.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dip54axBnIs

Casey N. Cep is a writer from the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

Cult Food Addictive

“Richie Scarpato, 25, a Yankees fan, had never been to Shake Shack but said it was a central attraction at the stadium. He had heard the story about the food poisoning but did not tell his friend, who stood by him in line. ‘I wanted it so bad, I did not think it mattered,’ he said.” People want Shake Shack so desperately that they do not care that Mets first baseman Lucas Duda and Philadelphia Phillies Manager Ryne Sandberg, who lost six pounds in two days, may have gotten food poisoning from the Citi Field location. Tobacco companies wish they had that kind of loyalty.

(This may be, of course, because Shake Shack is definitively better than In-N-Out.)

Gentry Horny

“Sometimes it’s hard for poly people to find housing where’s there’s no judgments,” said Leon Feingold, the realtor showing the property. ‘Where people aren’t always asking them to keep the noise down, or ‘who are these people that are visiting you?’ and ‘why don’t you have a normal boyfriend like everyone else?’” — Bushwick’s new exclusively polyamorous residential property is looking for tenants.

The Artisanal Troll

A society should really only be judged on the quality of its trolling. Some trolls are obvious, some are subtle, some are dumb. (Some are all three.) But some trollery approaches pure critique, is made of the finest digital intervention, and only performed for a limited audience. It’s artisanal trolling! Hand-roll troll! (Is it really trolling if you’re not chasing a huge audience? Hmm!) Here’s Greg Allen going in on Twitter with the Cambridge University’s Digital Library’s… let’s say “ironically orientalist” take on a very beautiful 16th century Islamic manuscript version of Zakariya Qazvini’s cosmography.

Some trolling is successful even!

@gregorg @vhfscott brilliant! Now I see that this is clearly the correct interpretation

— CambridgeDigitalLib (@CamDigLib) May 15, 2014

New York City, May 13, 2014

★★★★★ It was necessary to deliver a jacket to the school after the first-grader had headed off in short sleeves, though maybe it would not really be necessary by the time recess arrived. The coolness was pleasant, and mild exertion or extended sunshine was all it took to make it not cool at all. Nothing about the feel of it could have been improved. The sun edged into the gloom of a Starbucks; it lit up a layer of golden dust on the touchscreen of a MetroCard machine. Light brushed the bright parts of the metal treads up the subway steps. Indoors was sweltering, then freezing, as the thermostat chased futilely after the perfect balance available outdoors. An office footrace, the subject of theorizing and argument for who knows how long, was suddenly set up for real on the shady street. The leader flagged; the trailing runner overtook him in the final stretch; a black sedan tolerated the whole production. On the way to sundown, delicate yellow-pink ruffles formed on the cloud bottom, and a lingering shine gilded the top of a crane angled upward. The ruffles turned fully pink, and wide, pink searchlight rays fanned out across the sky.