A Man Walks into a Boxing Ring

by Matt Chmiel

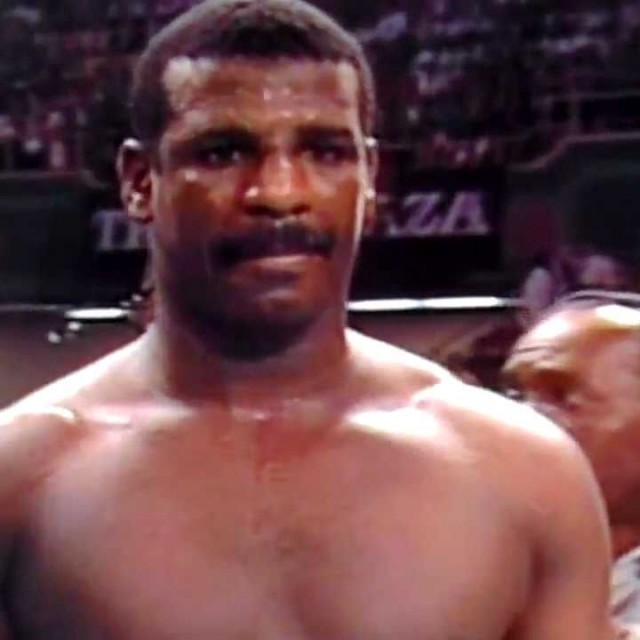

Mike Tyson fought fifty-eight times in his twenty-year career. Chances are, you only remember a handful of those fights. Chances are even better that his bout against Michael Spinks on June 27, 1988, is one of them. History blessed this night with an audacious moment that should have granted it pop culture immortality, but sports got in the way: It took Tyson just eight punches over ninety-one seconds to obliterate a tentative and terrified and previously undefeated Spinks in one of the fastest heavyweight title fight KOs ever. But the real story occurred minutes before the round-one bell: Tyson’s ring entrance, the slow spectacle squeezed into every big boxing event, was a masterpiece.

The ring entrance is a curious ritual, saved for boxing’s biggest bouts. It’s a necessary but forgettable part of the vaudevillian stagecraft behind multi-million-dollar sports entertainment. The weigh-in ceremony, the ring entrance, and the pre-fight face-to-face transmogrify the brutality of the ring into a Hollywood-style narrative of two titans, two half-gods, locked in glorious battle. Without these little performances, the audience might realize that it’s paid a lot of good money just to watch two regular dudes punch each other.

Google the best ring entrances in boxing, and you will see a range of spectacle. On one end, extravagant fighters wink at the audience, making a wry joke out of the whole scene; success is measured by the audacity of the joke. The most obvious and hilarious example was when Prince Naseem Hamed flew a magic carpet on a cloud of stage smoke into the ring. (He won, by the way.) On the other end, you have every boxer who has ever played LL Cool J’s “Mama Said Knock You Out” and stormed to the ring with a pumped-up entourage. The explicit point is always the same: This person is tough. Somehow, though, Mike Tyson discovered a third option: a fully conceived piece of performance art.

At the time, Tyson was an ascending force in the world of professional boxing. He was the youngest heavyweight champion in history, quickly collecting thirty KOs in his first three years as a pro. But Michael Spinks presented a serious challenge: He was also undefeated, and a heavyweight champion in his own right. The promoter angle for the fight was “once and for all,” with the winner becoming the undisputed heavyweight champion. So Tyson couldn’t just defeat Spinks — he had to destroy him.

Spinks came to the ring first, in a white robe, to a song that Kenny Loggins wrote after visiting his father in the hospital. Loggins once described it as “not a love song, it’s a life song.” Considering the context of the fight, the track is mildly alarming in its sentiment: “Make no mistake where you are / You’re back’s to the corner.” But it’s of a piece with the desperate energy Spinks seemed to be channeling to compel his body to withstand the awesome power of Tyson. After he made it to the ring, Spinks hopped and paced and bowed to the crowd from his corner. Muhammad Ali, wearing in a business suit, leaned into Spinks for some last minute encouragement.

Whatever power of Spinks’ entrance had immediately evaporated when a deafening drone of noise started swirling in the air. As it crescendoed into a maddening roar, the crowd at the Atlantic City Convention Center arched to follow the procession of men, all cops and security guards, emerging out of Tyson’s locker. Tyson, bare-chested and already soaked in sweat, slowly materialized from the back and meandered to the ring, barely blinking. The broadcast announcer Bob Sheridan, struggling to define the scene, played it straight: “It’s interesting Mike Tyson selected as his pre-fight music just noise; every once in a while you hear the clanging of chains. I think that’s what he’s got in mind to do to Mike Spinks’ head, but we’ll wait and see. Everything that Tyson does is intimidating.”

The “noise” was in fact a song by the British band Coil, an experimental, post-industrial noise outfit — all descriptions in the indie-music taxonomy for loud, chaotic, undulating electronic sound with a formless sort of purpose. Coil was founded by John (or Jhonn) Balance and Peter Christopherson in 1982. Their music was inspirationally weird and alienating; it conjured a mysterious force that was terrifying, compelling, illogical, and intentionally unpleasant. Producer Clive Barker said that Coil was “the only group I’ve heard on disc whose records I’ve taken off because they made my bowels churn.” The Coil manifesto states:

COIL know how to destroy Angels. How to paralyze. Imagine the world in a bottle. We take the bottle, smash it, and open your throat with it. I warn you we are Murderous. We massacre the logical revolts. We know everything!”

Coil were, in other words, the perfect band with the perfect song for Tyson’s performance, flaunting his own raw and dissonant rage and power. He wasn’t saying, like most boxers, “check out how awesome I am.” He was saying “I don’t know karate, but I do know ka-Razy.” It was a terrifying spectacle, a twisted accomplishment. It was show, don’t tell. It was art. The next time someone brings up Tyson vs Spinks, set everyone straight when they start talking about the ninety-one second knockout, because Tyson did something way more meaningful that night with his mind than he did with his fists.

Matthew Chmiel works at the design agency Code and Theory.

New York City, June 17, 2014

★★★★★ The bedroom was already hot at the moment of waking, and the kitchen trash had ripened overight. Melon guts, probably. Edges of buildings were flat against the white glare. The breeze could still be construed as cool, though the moving air was damp and heavy. Enough Citi Bikes were out in use that it was easy to jaywalk through the rack. A lawnmower raised the smell of cut grass from the not-exactly-public garden. There was nothing discouraging about walking out for lunch. No, more than that. The generous loveliness of the previous days was of course gone, but in its place was the compelling feeling of hanging on the brink. A limited-time offer. Sweat glands were not yet sweating; the heat still quickened the nerves, rather than stunning them. Elderly ladies carried umbrellas as parasols. The Freedom Tower stuck up over the Bowery, blue-hazed. Late in the day, tiny air-conditioning droplets blew overhead into the lowering sunlight, a private meteor shower.

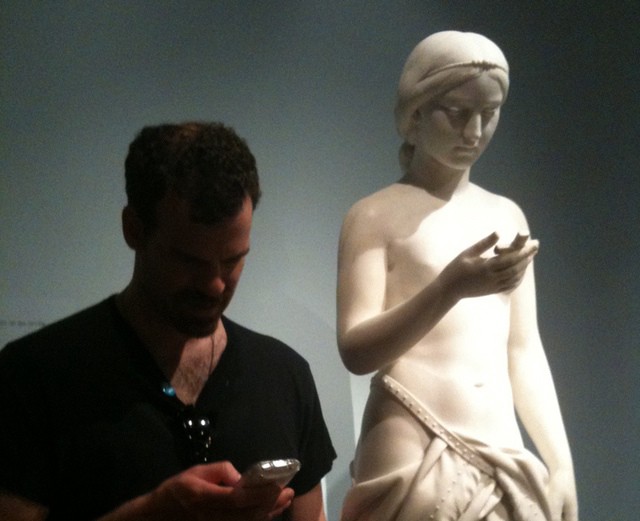

Museum Innovates

Attendance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art reached a record high of 5.68 million people in its fiscal year 2011; it rose again, significantly, to 6.28 million in 2012. It fell, slightly, in 2013, to 6.2 million. Attendance numbers for fiscal year 2014 should be available in two weeks or so.

But, while attendance may be flat (or not! we’ll see), have you checked out how many followers the Met has on Instagram?

After the pictures were posted, the museum saw its account gain thousands of followers. Then Instagram itself listed @metmuseum for two weeks as one of its featured accounts for new users to follow. Traffic jumped by 20,000 followers. Mr. Newby said that wouldn’t have happened without Mr. Krugman.

Now #emptymet tours occur almost monthly. Mr. Krugman has led about a half-dozen of them, with the balance being run by other Instagram users from across the world who lobbied the museum for special access. The Metropolitan Museum’s main account, less than 18 months old, now has over 170,000 followers.

It may or may not be a question for the Met if these followers, particularly ones who’ve not visited the museum, will become visitors or mere voyeurs; in the age of #crushingit even the most elite of cultural institutions apparently needs a #brand.

Photo by Richie Nakano

Where Will Your Pacifico Bottle Take You?

by Awl Sponsors

Discover the secret, hidden treasures of Baja and beyond this summer. One bottle at a time.

Pacifico first came to the U.S after it was found by American surfers while searching for waves along Baja’s beautiful coast. Because of this, Pacifico has an authentic spirit of discovery. Which is why now, under every iconic Pacifico cap, you’ll find the latitude/longitude coordinates to one of twenty-one incredible adventures such as kayaking, snorkeling, spear fishing, and sand-boarding!

So this summer, grab a Pacifico and discover the best of Baja and beyond. Whether it’s a glittering waterfall oasis in the midst of miles of dry, sunbaked lands, or an exhilarating dive into clear blue waters for some Hawaiian sling fishing, you’ll be inspired by each and every spot.

Check out this video for a taste of what’s out there and see more at http://discoverpacifico.com.

Ask Polly: How to Be Nice

Hi Polly,

One of the goals I have set for myself this year is to be a kinder person: more supportive and forgiving of my friends, more friendly and open to people I’ve just met, more approachable and compassionate with strangers. The problem is that this is a huge struggle because I am not naturally compassionate with people I don’t already like.

I have two reasons for wanting to be kinder: to ~make the world a better place~ in an abstract karmic kind of way, and also (this one is selfish) to fight against my depression, defensiveness, and general negative attitude toward life by opening myself up to more experiences. The first one is all well and good, but it’s not such an immediate motivating force, and the second one has its own built-in issues. When you’re already sensitive to the thought that people won’t like you, any small “no” and any negative aspect to a person makes you shrink away and turn your back preemptively.

Both my parents have very negative personalities and apparently deal with it in one of two ways: by sinking into a nasty, angry depression-pit or by maintaining iron control of everyone and denying that anything is wrong while things melt down around them. They had an acrimonious divorce about 10 years ago, when I was in middle school, and things are still raw. Being seven years older than my younger sister, I became her advocate and protector, and also tried to smooth things over between my parents wherever I could. I have definitely learned a lot of criticism from them, both of myself and of everyone else.

I’ve been working really hard to be less judgmental and the constant negative mental narration is much better, but I still catch myself evaluating new people that I meet for their quality as a friend, and if I don’t feel that they meet up to all these expectations I have of intelligence, being interesting, being accepting, etc., I don’t spend any time or effort getting to know them better. I find a lot of people tiresome, boring, annoying, etc., and then make no effort to disguise my annoyance with them. It’s really asshole-y. Even with my friends, I’m not as gentle as I would like to be. I snap at them if I’m in a bad mood, I’m not as forgiving of their imperfections as they are of mine, and I’m told that I’m an intense conversationalist, I strongly defend my opinions, and that I have a lot of them.

Plus, I’m hungry for a relationship with emotional intimacy, but when I begin to get close to someone that I feel safe with and attracted to, they don’t feel the same way. Either that or they are attracted to me “too much” or whatever, or want things to be too serious, and then I leap away myself. It’s fucked up!!! (This is complicated by my bisexuality, because sometimes I will get intensely emotionally close with a girl, feel sparks flying, try to make a move, and she will tell me she loves me but only as a friend.)

The best and most beloved friends that I have are so generous with their emotional energy, their compassion, their interest in someone else’s life, and it looks as natural to them as breathing. I try to open up to everything life has, and be kind and compassionate, and let things happen to me, and I’m burned out and even snappier and more defensive than ever after two measly weeks. Self-compassion is an important part of this (right?) and I’ve really been improving with negative self-talk, body image, blah blah, but I can’t seem to shake the outward-directed nastiness.

I guess the dilemma here is: How do you continue opening yourself to the world when you’ve been burned (or thought you’ve been burned, or burned someone yourself) so many times? How do you take your shriveled up angry sad heart and rehydrate it?

Thanks P.

Nasty Girl

Dear Nasty Girl,

As a former/occasional Nasty Girl, I take great satisfaction in thinking that Ask Polly might serve as a beacon unto the nasty, a place of refuge for those sharp of tongue and intense of conversation, who are gently and not-so-gently corrected by others, over and over again, like naughty little dogs on choke chains who will never, ever learn. Some of the greatest and most talented writers and artists were nasty motherfuckers who could never, ever learn — but this world we live in has maybe the lowest tolerance for nastiness ever. We, perhaps unfairly or perhaps logically, associate nastiness with prejudice and hate crimes and running over poor children in your Hummer and kicking poor kittens with your $4000 Hobnailed Prada Platform Ankle Boots. Nastiness is treated as a byproduct of religious fervor or racism or ignorance or misogyny or extreme privilege.

But what about nastiness that’s a byproduct of the soul’s gentle bleatings, from deep within, over the supreme stupidity and obvious terribleness of what passes for pleasant conversation today? What about nastiness that rises in one’s throat when one observes the popular dipshits of the world, raking in millions with their mediocre flailings, while thoughtful eccentrics wallow and languish in obscurity? What about the nastiness that bubbles up when one realizes that some of one’s closest compadres are content to blather endlessly about the same old tired shit, repeating tropes they’ve heard on TV and in strident but gutless Op-Ed columns and in bland, repetitive nonfiction bestsellers in which one single stupid idea (Work Less! Be More French! Psychopaths Are Fascinating!) is belabored in sloppy sentences that tangle together in terrible stultifying piles?

Please understand I’m not arguing against bad taste so much as laziness. I’m certainly not taking a stand against, say, watching the Stanley Cup finals and high-fiving over fried cheese and watery beers, which sounds awesome. I’m not even talking about thoughtlessness, because a lack of neuroticism can be refreshing, as long as it’s not accompanied by shitty judgment and the dull, humorless, rigid nothingness that today passes for an acceptable personality, as long as it’s sugared over in today’s appropriate flavors of Yes Man affability.

So let’s just acknowledge that today’s world may abhor grumpy assholes, but many grumpy assholes are thoughtful and open-hearted, and many open-hearted-seeming types are inwardly rigid and ignorant and blind in ways that fuck the semi-aware, fuck the planet and everything on it, and fuck the small and the oppressed who are struggling mightily to get a foothold in a cruel world.

Another tough thing is that, when you’re young, you can really screw up your entire worldview if you lazily persist in hanging around people who don’t make the least bit of sense to you. For example, I was once drawn to those who drank the most and smoked the most pot without getting sloppy or weirdly sentimental. I liked sharp teeth and snide remarks and also the occasional high five. Not total dicks, mind you — I do have deathly accurate dick-dar. But I have always had a weakness for a good rollicking gaggle of funny, emotionally withholding escapists and addicts and also just basic dudes who like deconstructing mindless blockbusters. Those who are allergic to talk of feelings. Condescenders. And also gushing enthusiasts. How do they find each other? They do, and when they do, they high-five over having found each other.

Even as I write this, I long for that swaggery douchebag scene a little, because there was a lot of bluster and self-confidence in the mix. But here’s the thing: As a nasty intense woman without the proper disguises in place, it’s very difficult to let your glorious freak flag fly among conformist high-fivers. They don’t know they’re conformists, of course, since they’re all smart and weird in their own high-fiving way. They make observations, they have senses of humor. But when you throw out your own loose, nutty shit, they kick it away and snort and you are agreed to be Not Quite Right. Some conformists will only embrace ideas that come out of crappy repetitive nonfiction bestsellers and sportscasters’ mouths.

Conformists need a strong leader to tell them who to like and who not to like, whether that leader is on the TV or in fully sanctioned and embraced books. If you’re not a leader and you’re young and not that strong, they are going to tell you everything original and flawed and brilliant about you is fucking queer and stupid. SO FUCK THEM. Sometimes you feel unkind around people like that because you know that they’ll never make space for you. Noticing this is not nasty, it’s adaptive.

At age 21, surrounding yourself with people who reflect your own self-hatred back at you is a fucking catastrophe. By the same token, if you’re running around with tons of self-hatred on board, most social relations are going to get pretty catastrophic.

Case in point: Let’s talk about truly open-hearted women who support exactly who you are. I had friends like that in high school, somewhat miraculously. Because I was angry and was so used to being rejected by my own undeniably loving but confused Little Brute Family, I didn’t realize it. I assumed my high school lady friends were faking it, that they didn’t really love me the way they pretended to. I felt this way because I didn’t understand how to love them for who they were yet. And when one friend tried to hook up with MY hook up (not even a boyfriend), I was ENRAGED. That proved she didn’t really love me — it proved that NONE OF THEM loved me. I thought I was the only one with Real Feelings and everyone else was cavalier — they simply knew how to ACT like they cared. I thought they were masters of illusion.

So that’s when I chased after the swaggery douchebags described above, in college and maybe beyond.

It took so much time and distance to make sense of all this. I had to write a memoir about my confusion, just to make sense of it. My book is all about beating back your own nastiness and fear and confusion after growing up in a Little Brute Family.

There are obviously a million abstractions and conflicts to explore here, but let’s get concrete. You want to be a kinder person. Quieting those self-hating sounds in your head, as you’ve been trying to do, is definitely the first step. When a voice in your head says, “You are such a fucking asshole. You are so impatient and fault-finding, just like your mother,” you have to notice. Just noticing is sometimes enough, because over time you’ll say, “Jesus, every single tiny thing I do is a major mistake, according to this voice.” And the voice will get quieter and less relentless, slowly but surely.

Remember that everyone with a conscience and a tough past eats themselves alive if they don’t work hard not to. You are who you are and you are trying hard to improve yourself. You’re working at acceptance. And maybe you need to accept that life is not endless communing with smart, hilarious, like-minded geniuses. Everyone is flawed. Everyone can sound boring at some point. People often — OFTEN! — sound much more trivial and shallow than they actually are. That’s how we’re taught to sound, in our culture. Trivial and shallow win the day.

So accept your flawed, moody self and accept the flawed, moody, annoying world around you. Shallowness is sometimes a retreat from darkness. High-fiving is a way of celebrating small shit, as a means of not feeling contemptuous or sullen about bigger shit. When you’re young, you don’t know that almost everyone around you struggles with their own judgments and nastiness and moods. People are usually more complicated than they appear.

The better you get at allowing yourself space to be flawed, the better you’ll be at not lashing out at other people’s flaws. And the better you’ll be at turning your back on people who basically don’t like you. People who do love you are almost always worth keeping, even if they themselves are very different from you. If they support your weirdness, and allow you space, then you should work to support them, too. When you really lean into differences, explore them, take an interest in them instead of feeling threatened by them, then it’s possible to celebrate them. It’s possible to be that kind person you want to be without making a Herculean effort to do so. Taking a real interest, asking questions, shutting off your bad shriveled brain and exploring in a new land, is much more substantive and rewarding than simply TRYING TO BE NICER.

Writing down what you’ve learned and observed about your friends and other people can help. Sometimes you won’t like what you observe. But other times you’ll let your friends and acquaintances blossom and show their weird selves and you’ll be able to appreciate them. Writing down what you’re grateful for every night also helps to cultivate gratitude, and open-heartedness. Any writing you do that allows your feelings to flood in, even if it’s all anger and sadness some days, is going to help you.

But you also have to know your own limits and respect them. If you start compulsively giving and giving and giving, that won’t do shit for you. It will only make you dislike everyone, and dislike yourself for not being someone who can give endlessly. Give what you can, but don’t overachieve. Let yourself be a fucking person. This is one of the big lessons of motherhood: when you give much more than you can naturally tolerate giving, it just makes you grumpy. Your kids don’t need that. An hour of total focus and enthusiasm, offered after you exercise and get a little work done, feels much healthier and happier for everyone involved than several long hours of half-assed trying to “bond” while feeling pissy because you’ve been pulling ugly outfits onto Barbies for too long.

So that’s what I’d say: Embrace who you are. Give yourself space. Shut down the “fuck you” voice in your head. Respect your own limits. Do what you can but don’t do what you can’t. Don’t punish yourself for being you. And don’t spend time with people who aren’t equipped to embrace you or appreciate you, who will tell you you’re rotten simply because they hate difference.

Nasty Girls can be open-hearted, if they embrace their own flaws, if they embrace their softness, if they embrace the inherent contradictions therein, if they embrace the inherent contradictions in everyone else and in everything else. People who righteously point out contradictions all the time are usually people who are too rigid and dumb to recognize that each and every one of us is in conflict constantly. The most serene Buddhist in the universe recognizes that contradiction lives at the center of everything. People who claim moral high ground or even total consistency are not to be trusted for a second.

Right now you’re trying hard to be nicer and more open-hearted, but you’re bludgeoning yourself for it. “BE KINDER, ASSHOLE! BE NICER, YOU SORRY OVERLY CRITICAL PIECE OF SHIT!” The soul rebels from that. It will make you even meaner if you don’t respect its wishes. When I say to myself, “WRITE FASTER! BE MORE BRILLIANT, YOU SLUGGISH FUCK!” the fairy godmother in my soul says, “Bibbedy bobbity boo! You will now be devoid of original creative thoughts for days on end!”

You are becoming kinder, and sometimes you feel really angry and mean. That’s OK. Give yourself credit for small efforts, and give yourself credit for WANTING to be kinder, which proves that you aren’t the total dick you think you are. Give yourself credit for having a sharp mind that likes to slice and dice. Give yourself credit for having friends who do care, who love flinty, frustrating you, in spite of everything.

Give yourself credit for being a Nasty Girl. Dave Chappelle and Lorde and Joan Didion and Kanye West and Tori Amos and Jonathan Ames and Elaine Dundy and Adrienne Rich are all nasty girls. John Updike and Cynthia Heimel and Sofia Coppola and David Chase and Stevie Nicks and David Sedaris and Jennifer Egan and Kim Gordon and Iris Owens are nasty girls, too. It’s ok to be bored and annoyed and sick inside. Put it somewhere. Write something freakishly mean and scathing and gloriously self-aware and self-abnegating and grandiose and sad. Create something soaring and melancholy and frustrating. You are full of so many charged, combustible thoughts and feelings. You are full and rich and alive and you deserve to feel what you feel and be who you are. Celebrate the nasty. Lean in, Nasty Girl. Lean the fuck in and be nasty. Not callous. Not withdrawn. Not punishing. Not escaping. Not self-destructing. Engaged and furious and generous and heartbroken and glorious and nasty, nasty, nasty.

Polly

Do you want to wash away all of your nastiness and replace it with a healthy golden glow without chemicals that have been tested on animals? Write to Polly and discuss!

Heather Havrilesky (aka Polly Esther) is The Awl’s existential advice columnist. She’s also a regular contributor to The New York Times Magazine, and is the author of the memoir Disaster Preparedness (Riverhead 2011). She blogs here about scratchy pants, personality disorders, and aged cheeses.

Photo by Alias

Commute Interrupted

Do you remember where you were this morning, starting at 9:36? Are you sure? Think carefully. Put yourself back there, and try to interact with your environment. Is it just you, or does something not add up? You can remember the people, certainly. But can you remember their faces? The ride passed, it must have, but did it happen?

You got to work — you can recall closing the door to your home, and opening the door to your office — but what happened on the way? Your memory is like a hard dial that refuses to sit in the middle notch. Before, click, fine. After, snap, ok. But the middle is a slippery peak — there is no stopping. You try to keep momentum, coasting from moment to moment to moment until you reach your commute. There is a skip. A clean but obvious edit; the implication of lost footage.

Do you remember where you were this morning, starting at 9:36? Are you sure? Think carefully. Focus on the void, as unsettled as it makes you feel. Yes. Yes. It is all becoming clear now. Remember what we saw? No, impossible. Before you speak, consider the consequences.

Tove Styrke, "Even If I'm Loud It Doesn't Mean I'm Talking to You"

Should you find yourself at some point today overcome by torpor, perhaps due to climatic conditions in your area or simply the prevalence of complaints concerning climatic conditions on social media, this song may provide a brief burst of energy before the fatigue inevitably takes hold once more. Yes, it’s going to be hot. The sun will scorch your pasty skin and lethargy will lay its heavy hand upon your sweaty shoulders as it implores you to join it on the couch. But consider: We are barely past June’s midpoint here, people. Don’t waste all your whining just yet; think of how disappointed you’ll be with yourself come August when folks are spontaneously combusting in the streets and Twitter is full of photos showing New Yorkers literally melting onto the sidewalks below their feet. And gentlemen? Please don’t even think of asking me if you can wear little-boy pants just yet. STILL JUNE. Wait, where was I? It’s like I have forgotten how to do this already. Oh, right. This song is pretty catchy. I tapped my feet at least, and, really, on a day like today, you can’t hope for all that much more. I mean, you can hope, but I think we both know how that usually works out. Anyway, enjoy. [Via]

War Is Synergy

“’Airstrikes will have only one good effect: to bolster morale of the Iraqi Army,’ said the retired American general, who spoke on the condition of anonymity so as not to jeopardize business relations in the Middle East.” (via)

New York City, June 16, 2014

★★★★★ The two-year-old stood on top of the heater to look through the window and enumerate the construction workers across the avenue, as the morning light shone into the seven unglassed top floors of the tower. Yellow hat, blue shirt. White hat, white shirt, blue pants, bright green gloves. Red shirt, white hat. Dust floated off the edge where one of them — wardrobe colors indistinct in the shadows — ran a polishing machine over the slab. Out the front doors, water sparkled where it flowed over the fountain’s edges. People had stripped down without strain or overheating; chests and tattoos were showing. The sky was pincord blue. Bamboo and other plantings peered over the cornices, six stories up. Flags of World Cup countries stuck their free ends out of a restaurant window. The round-toned roar of television carried out into the rush-hour street, on the open air.

Marc Andreessen and the Inevitability of Catastrophic Ideas

Greed is right, greed works… Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind. And greed, you mark my words, will not only save Teldar Paper, but that other malfunctioning corporation called the USA. Thank you very much. — Michael Douglas in the character of Gordon Gekko, in Wall Street

c

Gordon Gekko was meant to be a villain, but he became a plutocratic folk hero. There has been greed enough in the last thirty-seven years, surely, to have transformed the USA into a positive utopia according to the Gekko formula, with prosperity for all.

Has the USA been saved? LOL nope.

Whether promulgated as supply-side or trickle-down economics — or the Objectivo-duncianism promoted over Twitter by Netscape founder and rabidly successful venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, it’s all window dressing for what John Kenneth Galbraith used to call “the horse-and-sparrow theory” as he described in the New York Review of Books in 1982:

Mr. David Stockman [director of OMB under Ronald Reagan] has said that supply-side economics was merely a cover for the trickle-down approach to economic policy — what an older and less elegant generation called the horse-and-sparrow theory: If you feed the horse enough oats, some will pass through to the road for the sparrows.

There’s little evidence that this theory has ever worked or can ever work.

We have had almost forty years of “free markets” — markets that are not merely open, but pointedly and performatively unaccountable — and here is what we have to show for it: Median household income has hardly grown despite huge increases in productivity, with wages as a share of GDP — the number we ought to be focusing on — falling to record lows, while an extremely small portion of the population has become inordinately, obscenely richer. But the triumphalists of Silicon Valley, their insulated worldview informed by an unholy stew of TED Talks, Lean In and Atlas Shrugged, appear to think otherwise.

Though he is a Silicon Valley mogul through and through, Marc Andreessen is no Tom Perkins. As tech zillionaires go, he seems to be one of the more decent ones — a nice guy, it is said, with a genuine interest in philanthropy. His wife, Laura (herself the daughter of a billionaire), teaches classes in philanthropy at Stanford. All six of the partners at Andreessen-Horowitz have pledged to give away at least half the proceeds of their venture capital careers in their lifetimes; the 2012 announcement of their pledge was paired with a gift of $1 million to six different charities. Still, charity, even in sizable amounts of it, does not inherently absolve the world’s zillionaires of criticism, particularly when it is evident that their taking played such a dramatic role in getting us into this mess in the first place. What if they took less, instead? Where are the tycoons who “give back” in the form of wages and benefits for their employees? This observation is to make the following point: What you will never find a modern plutocrat doing is promulgating any “innovation” that will curtail their own privileges.

In recent days, Andreessen has taken to Twitter to hold forth on socioeconomic matters in several series of tweets, about a hundred in total; they are hair-raising, particularly the seventeen-part series about how “tech innovation helps the poor.” The problems that the poor face are deep and structural, but the rich like Andreesseen show little interest in fixing them, preferring to trumpet the virtues of beautiful Band-Aids instead. The poor need a real path to educational achievement to even hope to escape their poverty; Andreessen and his cohort proffer MOOCs. The poor need a way to move around cities to get to far-flung jobs; Elon Musk is talking about hyperlooping between SF and LA for his buddies.

1/Technology innovation disproportionately helps the poor more than it helps the rich, as the poor spend more of their income on products.

— Marc Andreessen (@pmarca) June 4, 2014

It’s difficult to figure out what is meant here, exactly. Is this just plain warmed-over Objectivism, straight from the decayed paps of Ayn Rand? Or what? Marc Andreessen is the direct beneficiary of “technology innovation” to the tune of several hundred million dollars. And yet, he claims, the poor have somehow been helped still more than he.

Here’s the rest of the June 4th series:

2/This sounds like it must be a controversial and politically charged position, and yet it is not — it flows from basic economics.

3/The best way to understand this is by historical example: What the rich used to have and what the poor now have, due to tech innovation.

4/Rich have always been able to pay servants to wash dishes; due to tech change, now most US homes have automatic dishwashers.

5/Rich have always been able to pay servants to wash and dry clothes; now most US homes have automated washers and dryers.

6/Rich were able to afford to have fresh ice delivered daily to make iceboxes work; now all American homes have refrigerators.

7/Rich were always able to afford to hire musicians to play in their homes; now audio equipment and digital music are cheap for everyone.

8/At one point only the rich could pay for horses, buggies, stables, coachmen — now cars are easily affordable by almost everyone in West.

9/Go far enough back, only rich could afford hand-copied books or to employ scribes; printing press made books accessible to the poor.

10/Technology innovation is the main process by which luxury items become produced, packaged, and made affordable for everyone.

11/Opposing tech innovation is punishing the poor by slowing the process by which they get things previously only affordable to the rich.

12/And, tech innovation is the process by which everyone in the world will be able to afford things that are plentiful in the West today.

13/A great lens on this is the US HUD housing survey; shows rapid material progress of poor Americans quite clearly. http://portal.hud.gov/hudportal/HUD?src=/press/press_releases_media_advisories/2010/HUDNo.10-138

14/Note that consumer costs rising most quickly (education, health care) have least tech innovation and least market competition.

15/This is Baumol’s Cost Disease: http://www.amazon.com/The-Cost-Disease-Computers-Cheaper/dp/0300179286/ref=pd_sim_sbs_b_2?ie=UTF8&refRID=05X070VAH6JAR7SFFY4H http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baumol’s_cost_disease http://www.economist.com/node/21563714

16/The way to make health care and education more affordable for more people is more tech innovation, not less. Push onto tech price curve.

17/if you object “not ALL poor can afford product X”: The answer is more tech innovation to drive price down further, in every case.

In these few brief remarks, Andreessen manages to mention the “rich” nine times, and the “poor,” seven; “people,” just once, and “human,” not at all. What the supply-side formula really does is provide the rich with a crucial delusion: It creates two kinds of people, a superior and an inferior kind, so that the rich can then situate themselves in the higher, better, more important class, separate from the lower. This absolves them of any real responsibility even to think about those lesser ones as equals, as fellow human beings — because just by their regular doings, their entrepreneurial drive, they are magically, effortlessly helping The Poor.

Sixteen or seventeen percent of Americans are living in poverty, the 2014 federal guideline being $23,850 for a family of four. The millions living in circumstances this reduced do not buy much in the way of “products”. They can’t. (Payday loans! I guess they can buy.)

The concrete benefits Andreessen claims the poor are receiving because of “technology innovation,” according to his various tweets of June 4th, are as follows:

• dishwashers

• washers and dryers

• refrigerators

• audio equipment and digital music

• cars

• printed books

That doesn’t quite seem to add up to “the good life,” does it? Low-income Americans may have the use of kitchen equipment in their rented apartments, (more rarely a washer or dryer) but the cost of gas and insurance makes it impossible for many to drive even a used car. (The HUD survey Andreessen cites doesn’t count mobile homes or trailers.) Used audio equipment is plentiful at thrift shops (though maybe not iPods or even MP3 players), okay. It’s hard to avoid the impression that Andreessen’s “poor” are in fact some lost, idealized version of the consumer middle class.

The final entry, “printed books” is the most illuminating. Though Gutenberg and co. had driven the price of books down substantially in the fifteenth century, they were still luxury objects for a long time after that.

An equally significant “technology innovation” with respect to the spread of literacy and books is the rise of the public lending library in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in which communities pooled their resources in order to make new books — luxuries then, as they are still — available to all. (In the United States, Andrew Carnegie granted funds to build more than 1,600 libraries, all contingent, though, on the community’s willingness to raise taxes to share the cost.) We still use this method of disseminating books and information to the poorest Americans. Nobody ever got rich as a result, either.

It’s not false to say that some crumbs perforce will fall from the tables of the rich onto those of the poor. It in no way follows, however, that that is the way bread should be shared.

16/The way to make health care and education more affordable for more people is more tech innovation, not less. Push onto tech price curve.

— Marc Andreessen (@pmarca) June 4, 2014

An education is not a refrigerator, nor is it a dishwasher; it is not a “product” to “Push onto tech price curve”. It should be free to anyone capable of benefiting from it — via the investment of our pooled resources — not merely “more affordable.” The Silicon Valley notion that you can deliver education through a vending machine is of a piece with Andreessen’s two-dimensional view of socioeconomics. So easy! Program a MOOC, film a professor, test the student and see what his score is afterward.

He was educated in public schools, and he should be ashamed of himself. Though in some ways I can’t really blame Andreessen or his cohort for thinking as he does: He’s a meritocrat, simply carrying out the programming of American cultural institutions.

Michael Young warned against the rise of people like Marc Andreessen in his 1958 satire, Rise of the Meritocracy, and all his predictions came exactly true, as he lamented in writing in the Guardian in 2001:

If meritocrats believe, as more and more of them are encouraged to, that their advancement comes from their own merits, they can feel they deserve whatever they can get.

They can be insufferably smug, much more so than the people who knew they had achieved advancement not on their own merit but because they were, as somebody’s son or daughter, the beneficiaries of nepotism. The newcomers can actually believe they have morality on their side.

So assured have the elite become that there is almost no block on the rewards they arrogate to themselves.

One of the worst misapprehensions in Andreessen’s worldview is that creativity and inventiveness and “progress” are tied exclusively to the drive to create wealth. They aren’t.

A lot of the twentieth century’s most valuable inventions and discoveries — GPS systems, the Internet — came straight from university and government researchers on salary. Not from people trying to get rich. Some, like Andreessen, have used the university or government resources made available to them and taken their findings to private industry. Many do not take that route. The scientists and astronauts of the Apollo missions at the time of the lunar landing were worshipped in America, though none were in it for the money; Albert Einstein did not get rich from his discoveries; Jonas Salk gave his to the world for free. It’s only very recently that making money was so tightly sutured to the idea of “innovation,” as if nobody would bother to try or make anything if there weren’t a potential fortune in it — which would come as news to Tim Berners-Lee.

New Yorker staff writer and Harvard professor Jill Lepore set out to challenge the inevitability of “disruption,” what Andreessen might call the principal tool of “tech innovation.” Citing the remarks of venture capitalist Josh Linkner, who said, “[T]he next generation of innovators… are dead-focused on eating your lunch,” Lepore remarked:

his job appears to be to convince a generation of people who want to do good to learn, instead, remorselessness. Forget rules, obligations, your conscience, loyalty, a sense of the commonweal. If you start a business and it succeeds, Linkner advises, sell it and take the cash. Don’t look back. Never pause. Disrupt or be disrupted.

Far from being a benefit to society or torch-bearers for “progress,” there is ample evidence that the “entrepreneurial spirit,” for which read the drive to create wealth, in the hypertrophied, monopolistic, megalomaniacal incarnation in which we currently find it in Silicon Valley, has been and continues to be terrible for the future of American business, society and culture.

There have been two very good rebuttals to Marc Andreessen in recent days: one from Andrew Leonard at Salon, and the other from Sam Biddle at Valleywag.

Leonard takes Andreessen’s economic argument apart clearly and neatly. But it’s Biddle’s piece that begins to explain what’s really gone wrong in Silicon Valley (and on Wall Street, and perhaps in the halls of power in general.)

In conclusion, [Andreessen suggests that] the fact that we aren’t all living in mud huts or clinging to the side of crevasses, babies bundled in animal pelts, is a feat of Silicon Valley. The affordability of a smartphone or a television has everything to do with uncritical, unwavering faith in “tech innovation” and some childish, abstract notion of industrial progress. It has absolutely nothing to do with, say, the legion of Chinese laborers working under deplorable conditions. Ignore the fact that that owning a dishwasher doesn’t mean your position relative to the rest of society is anything resembling good or fair — just be glad your standard of living has increased since the 17th century.

Not two weeks later, in response to Lepore’s piece, Andreessen posted a since-deleted tweet:

What does Jill Lepore, Ph.D. in American Studies from Yale, think about quantum entanglement?

The classification of human inquiry into the Sciences and the Humanities is a rough but useful one. In essence, the part that concerns itself with what can be measured, we call “science,” and that concerned with what cannot be measured, we call “the humanities”. The former field of study provides us with the means to operate more effectively in the material world. The latter (and the latter alone) grants us the ability to judge what goes on out there. This is a question of balance. The study of the humanities is for judgement, and it’s judgement that our age is sorely lacking. We seem to have forgotten that we even need it.

These two ways of looking at the world and considering our actions therein are like the right and the left hand of human consciousness. It’s far easier to navigate the world with the full use of both. But the irrelevance of the humanities is trumpeted through the media on a daily basis. We live in a scientific age, we are assured. Everything must be tallied, measured, “explained” (LOL until I die a thousand times) with a chart or a bunch of incomprehensible psychedelic blobs on an MRI scan. We no longer need the fuzzy, meaningless mumbo-jumbo of philosophy or history, or the airy-fairy study of literature, impractical ivory tower disciplines for people who “don’t live in the real world”!

This conviction is widespread, with the results that you see all around you.

Having apparently determined that the Scientific hand is superior to the other one, having determined that “practical” considerations demand that we must judge the whole of human progress by means of GDP, our era finds us trying to do everything one-handed. In the manner, in short, of Chairman Marc. (Thank god he’s not in charge of agriculture!)

Those affiliated with the humanities — who interest themselves in all the things that can’t be measured, but must be judged instead, like moral, aesthetic and philosophical questions — are experiencing a daily low-grade fever of dissatisfaction (or generalized rage, in the case of Sam Biddle) as we are daily sold on the inevitability of catastrophic ideas. In 2003, Donald Rumsfeld told a reporter that the OMB had estimated that the Iraq War would cost something less than $50 billion — the total sum, to be shared by the US and its allies. There would be “smart bombs,” plans laid by expert warmongerers, all kinds of precision.

None of this persuaded the people who’d read their history and learned about the politics, who were warning against the likelihood of disaster and of civil war and the emboldening of extremists, and who marched in their millions (many, many millions) in the streets of the world’s capital cities in early 2003. So it rankles in a particular way to see that the true cost of the Iraq War topped $2 trillion not long ago.

What is the study of humanities for? It’s to prevent this. To apply the lessons of history, and consider the possible costs to the future. To consider not only what will profit us but what will be right for us to do, and why. Andreessen, a dyed-in-the-wool measurer and chart-monger if there ever was one, is a man who would never even dream of a just world, where all would sit at the same table. He is the living example of what is lost when we value things only through the money they represent.

Maria Bustillos is a writer and critic in Los Angeles.

Photo by Fortune Live Media