A Real Chill Bear

Don’t you wish you were as chill as this bear? Take a deep breath. Let it out. Do it again. One more deep breath. It’s Friday. You are the bear. You. Are. The. Bear. Exhale. (via)

A Visit to the Less Famous But Definitely Bigger World's Largest Ball of Twine

by Claire Suddath

The World’s Largest Ball of Twine might just be the most famous example of a certain kind of American roadside kitsch, although I can’t figure out why. It’s not part of the funky, burned-out cars and wigwam motels along Route 66. It’s not in National Lampoon’s Vacation, which is where most of my road trip knowledge comes from. Was it in those Guinness Book of World Records paperbacks I used to read as a kid, next to an entry about the man with the world’s longest fingernails or the world’s fattest identical twins? I don’t know.

Two summers ago, my boyfriend Josh and I borrowed a Jeep from an overly trusting friend of his father and drove out west. From New York City, we traveled nine thousand miles across twenty-five states for a trip that would include my first attempt at camping, his first visit to California, and the invention of a new game best described as, “Turn on the country radio station and try to guess which societal woe will be lamented next.” (Alcoholism. Always pick alcoholism.)

On the third day of the road trip, about two hundred thirty miles into Kansas, we hit a small town called Cawker City, which claims to be home to about four hundred people; I suspect they were rounding up. Cawker City is home to the ball, which was started in 1953 by a man named Frank Stoeber. There’s a competing World’s Largest Ball of Twine in Minnesota that weighs 17,400 pounds, but it’s kept in a glass display case and no longer grows. Cawker City lets travelers wind twine around the ball, and as of 2013, it weighed 19,873 pounds.

Cawker City was named after E. H. Cawker, partly because he helped found the town in 1870, but mostly because he won a poker bet that gave him the right to name it whatever he wanted. For a while, the town did pretty well: It became a stop on the Missouri Pacific train line, and by the start of the twentieth century, it had grown to about twelve hundred residents, mostly farmers. They raised animals and grew corn and traveled into town to shop at the two-block line of storefronts that ran down the main road, which is called Wisconsin Street. In 1904, the New York Times ran an article about how Cawker City had more happily married couples than any other town its size in America. “Husbands and wives are actually in love with each other,” the Times marveled. The reason? “Absence of saloons.” The rest of the century then passed by, relatively uneventfully: The town built a park with federal work relief funds during the Depression, then turned it into a makeshift PoW camp for German soldiers during World War II. It had a non-twine tourist attraction: a bubbling saltwater spring — a sacred site for the Great Plains tribes — but the Army Corps of Engineers built a dam that flooded it in 1968.

On what was obviously a very boring day in 1953 — probably because there were no saloons — Frank Stoeber gathered scraps of twine that he’d used to tie up old hay bales and rolled them into a ball. Then he gathered some more. His neighbors heard what he was up to and started bringing their leftover twine. Soon it became a thing that people did: bringing twine to Mr. Stoeber, who’d tie the strands together and add them to the growing ball that he kept inside his barn. He did this for eight years, until the ball was eleven-feet wide. Then he rolled it into town and donated it to people of Cawker City, who took one look at it and thought, “Okay, we can work with this.” They built a little display patio for the twine, with white support beams and a red roof to keep the ball dry when it rained. The twine still rests there, on that patio in the middle of downtown.

There weren’t any people on the streets when Josh and I arrived. No restaurants open for lunch, nowhere to get a cup of coffee, still no saloons. Rusted cars sat on cinder blocks in the middle of overgrown yards that led up to houses, each one with a sagging roof and at least one broken window. Most of Cawker City’s family farms have either been bought out or gone bankrupt, and the young people have all moved away to places where they can get better jobs in air-conditioned buildings. Josh comes from a place that’s a little like this: Linton, Indiana, where the local shops are losing the battle against the nearby Wal-Mart. But Cawker City isn’t big enough for a Wal-Mart.

We parked the car in an empty parking lot beside the twine and ran up to see the ball.

“Huh,” I said. “That’s an awful lot of twine.”

“Huh,” Josh agreed.

No one ever tells you this, but the World’s Largest Ball of Twine isn’t really a ball. It used to be, but now it’s so big that when people add to it, they have to wrap their strands around the middle. Over the years it’s become much wider than it is tall, making it technically The World’s Largest Lump of Twine.

We hung around the twine for a while, reading the unexpectedly crabby informational signs (“If the ball is wet, it’s raining…if the ball is white, it’s snowing”). We took pictures and tried to see how far around it our arms could stretch when we hugged it. At one point, Josh leaned in and sniffed it. “It smells like my grandpa’s barn,” he said, and then went on this long, Proustian tangent about climbing hay bales in Indiana barns during his childhood. I sniffed the twine too, remembered that I grew up in a landscaped subdivision with streets named things like Jennifer Court, and concluded it smelled musty.

We wanted to get some twine and add to the lump, but we couldn’t find anywhere to buy it — or anything at all. On Wisconsin Street, the downtown storefronts were either boarded up, falling down or both. I looked inside one store and saw overturned desks, open cans of paint, broken two-by-fours and crumpled newspaper pages. Outside, the words “Cawker City Ledger” were still etched on the windows. Something else was in the window too — a copy of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night,” with a swirl of twine in the sky instead of a star. A few doors down we found Mona Lisa, smiling with twine. There were a dozen of these sun-bleached reproductions, all along Cawker City’s defunct downtown, each one with twine hiding somewhere in the picture: Warhol’s soup can, with a twine-themed Campbell’s logo. One of Degas’ ballerinas, pliéing next to twine. And “American Gothic” — although in that one, the ball of twine didn’t look entirely out of place.

Sometimes, another car would drive up to the ball of twine. Josh and I watched as people climbed out, took a few pictures and then drove away. They never saw the paintings. Or the one window display that hadn’t yet been taken down. Someone had dressed four female mannequins as burly frontiersmen, then arranged them as if they were playing poker — a very progressive, gender-neutral reenactment of how the town got its name. On the sidewalk in front of them was a looping, curling yellow line of paint: a twine ball unraveling down the city street. It was the strangest display of economically depressed whimsy I’d ever seen.

We eventually found the Ball of Twine gift shop, but it had a “Gone to the Lake” sign hanging in the window, along with a note to try Lottie at the Almost Done Inn just a few blocks up the street. The inn turned out to be someone’s house, with the second-story rooms rented out to traveling twine enthusiasts. “Units equipped with or without kitchens!” a sign out front boasted. The women who greeted us wasn’t Lottie. She was her daughter — or maybe daughter-in-law, I’m not sure. Lottie was in the hospital she told us, something about her hip. “But she’s on the mend,” the woman kept saying, “I really think she’s on the mend.” The woman was barefoot and smoking. Behind her, a sheltie dog wouldn’t stop barking.

Lottie’s daughter-or-not-daughter showed us to a small bookshelf full of postcards, coffee mugs, and all sorts of souvenirs that Lottie had made by hand. Josh bought a replica ball of twine that for some reason had been glued to a rock. I picked out a clay toothpick holder.

“But you don’t even use toothpicks,” he pointed out.

“I bet if I lived in Cawker City, I would,” I said.

We asked for some twine too, but Not Lottie said there wasn’t any more for us to wind. So a toothpick holder and twine-on-a-rock were all we got. We paid twelve dollars, then walked back to the car. We weren’t more than an hour into our drive when Josh’s replica twine fell off its rock.

Claire Suddath is a staff writer for Bloomberg Businessweek.She lives in Brooklyn and actually prefers string.

Top photo by Adam Schweigert; other photos by author.

New York City, June 19, 2014

★★ Pillows of light gray were piled high against a duvet of darker gray. Off to the northwest was a still darker purple-gray bedskirt. The late push of heat had been a feint. A light rain spotted the metal edge of the curb. An open umbrella — unnecessarily open, and doubly unnecessarily staying that way — blocked the subway stairs with its slow descent. The gray lasted till late afternoon, and abruptly came sunbeams, blue sky, shadows. Early diners sat at white-clothed tables below sidewalk grade. The rain had evidently led people to excuse themselves from picking up dog turds, which had softened in the rain without washing away and were now re-solidifying in flattish discs on the sidewalk. “All ladies’ linen jackets, five dollars five dollars,” a sidewalk sample-sale barker announced on Broadway. The dinner table was sunny, but afterward, a new heavy gray mass appeared in the west, with an extra smoky darkness hanging down from its far-off northern end. The nearer part, though, was infiltrated by blue and laced with pink. The menace came no closer. At night, the air conditioner was off.

Lia Ices, "Thousand Eyes"

The SoundCloud commenting phenomenon deserves a little more attention. The posts, which on popular songs are numerous, aren’t comments so much as involuntary utterances: burps and farts and laughs and ooooohs; things that don’t usually get written down. They’re mashing the keyboard but they’re not angry. Anyway, agreed on all counts: “Nice,” “Thanks Nice song,” “F I R E,” “♡,” “Wonderful track and sound ! I wish have thousand ears 🙂 ♥ ♥ ♥.” [Via CoS]

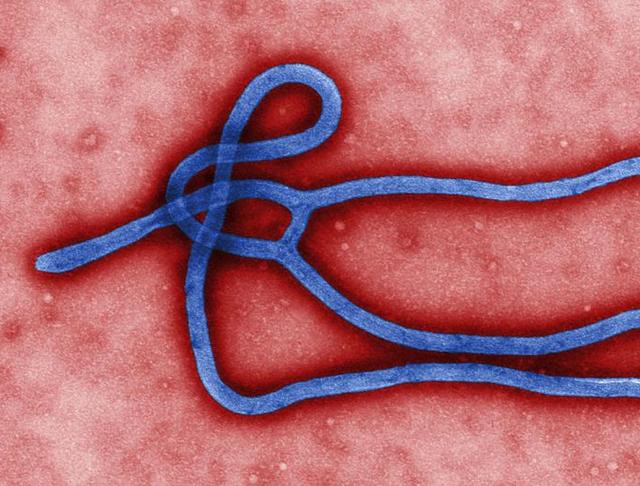

Ebola and You

Ebola and You

An outbreak of Ebola is on track to become the largest in history, and it’s showing no signs of slowing down. There are now over 500 recorded cases spread across Guinea and Sierra Leone; the last few appeared in Monrovia, a dense city with about half a million people (and another half a million clustered close nearby).

In the history of Ebola, this is Very Bad: It’s major outbreak in an unexpected location. But coinciding with this horrifying story seems to be a sterilization of the news itself — the b-matter in these stories is soft, considering. Here’s how NPR backs readers up:

Ebola often kills around two-thirds of the people it infects. And it kills quickly, sometimes within days, sometimes within weeks. That actually makes outbreaks relatively easy to stop, says of the University of Texas Medical Branch.

Here’s the AP in a wire stub:

Fear of the disease, which causes horrible bleeding and for which there is no cure, has hampered efforts to isolate the sick.

A longer AP report doesn’t bother to describe the disease, suggesting only that it’s very, very bad. Is the assumption that everybody already knows? Or is the collective sense of impending apocalypse so strong that it seems cruel to go into detail?

In any case here, for weekend reading, is a passage from one of the most terrifying books I have ever read, Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone, describing an early case of Marburg Fever, a hemorrhagic fever similar to Ebola.

He is holding an airsickness bag over his mouth. He coughs a deep cough and regurgitates something into the bag. The bag swells up. Perhaps he glances around, and then you see that his lips are smeared with something slippery and red, mixed with black specks, as if he has been chewing coffee grounds. His eyes are the color of rubies, and his face is an expressionless mass of bruises. The red spots, which a few days before had started out as starlike speckles, have expanded and merged into huge, spontaneous purple shadows: his whole head is turning black-and-blue. The muscles of his face droop. The connective tissue in his face is dissolving, and his face appears to hang from the underlying bone, as if the face is detaching itself from the skull. He opens his mouth and gasps into the bag, and the vomiting goes on endlessly. It will not stop, and he keeps bringing up liquid, long after his stomach should have been empty. The airsickness bag fills up to the brim with a substance know as the vomito negro, or the black vomit. The black vomit is not really black; it is a speckled liquid of two colors, black and red, a stew of tarry granules mixed with fresh red arterial blood. It is hemorrhage, and it smells like a slaughterhouse. The black vomit is loaded with virus. It is highly infective, lethally hot, a liquid that would scare the daylights out of a military biohazard specialist. The smell of the vomito negro fills the passenger cabin. The airsickness bag is brimming with black vomit, so Monet closes the bag and rolls up the top. The bag is bulging and softening threatening to leak, and he hands it to a flight attendant.

When a hot virus multiplies in a host, it can saturate the body with virus particles, from the brain to the skin. The military experts then say that the virus has undergone “extreme amplification.” This is not something like the common cold. By the time an extreme amplification peaks out, an eyedropper of the victim’s blood may contain a hundred million particles. In other words, the host is possessed by a life form that is attempting to convert the host into itself. The transformation is not entirely successful, however, and the end result is a great deal of liquefying flesh mixed with virus, a kind of biological accident. Extreme amplification has occurred in Monet, and the sign of it is the black vomit.

He appears to be holding himself rigid, as if any movement would rupture something inside him. His blood is clotting up his bloodstream is throwing clots, and the clots are lodging everywhere. His liver, kidneys, lungs, hands, feet, and head are becoming jammed with blood clots. In effect, he is having a stroke through the whole body. Clots are accumulating in his intestinal muscles, cutting off the blood supply to his intestines. The intestinal muscles are beginning to die, and the intestines are starting to go slack. He doesn’t seem to be fully aware of pain any longer because the blood clots lodged in his brain are cutting off blood flow. His personality is being wiped away by brain damage. This is called depersonalization, in which the liveliness and details of character seem to vanish. He is becoming an automaton. Tiny spots in his brain are liquefying. The higher functions of consciousness are winking out first, leaving the deeper parts of the brain stem (the primitive rat brain, the lizard brain) still alive and functioning. It could be said that the who of Charles Monet has already died while the what of Charles Monet continues to live.

And then read this, too, and never go outside again.

Random Acts of Preservation

Who is nostalgic for Kentile, the company that manufactured asbestos-laden flooring and collapsed under the weight of lawsuits two decades ago? Nobody: This is about the object. The sign’s appeal was that it was very large and conspicuously old, and it had decayed, naturally, just so, in a location where such a thing would never be built today. It is the most general possible signifier of change and history, and one more instance of a phenomenon playing out in cities across the country: This thing used to be new, and now it’s old; it used to be clean, and now it’s dirty; but it used to be, and it still is, so that’s cool. Now all Brooklyn makes is yoga. Brooklyn used to make tiles, in the Kentile factory!

BUT:

The President of the Gowanus Alliance, Paul Basile, has announced a partnering with local officials in an effort to preserve The Kentile sign’s iconic letters for continued display in The Gowanus area. He and the Gowanus Alliance will arrange to preserve, to hold, and to repair the letters while local officials seek a permanent location for the sign…

It will be rebuilt, possibly, somewhere else in the neighborhood. This seems both unlikely to succeed — the sign is very, very large — and counterproductive. The sign earned affection because it was stubborn and incongruous, not because of its specific history (or, to put it another way, the only part of its history that matters to people is the stretch where it had no reason to stand but still did, despite the odds, lingering for years); rebuild it in a location where it’s welcome and it loses its only power. Preserving it will have the unfortunate effect of turning it into kitsch. Or maybe that’s the point?

Gerry Goffin, 1939-2014

“Lyricist Gerry Goffin, who cowrote the hits ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow,’ ‘The Loco-Motion’ and ‘(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman’ with his ex-wife Carole King, has died in his home in Los Angeles.” He was 75.