Join the #UnitedWeShave Movement This Summer

Join the #UnitedWeShave Movement This Summer

by Awl Sponsors

This Independence Day, Schick® Quattro® is inspiring guys to reclaim their chins, buck beards and make this the summer of the jawline.

Guys, stop hiding your face and take back summer for the clean shaven because it’s hip to be square jawed with Schick® Quattro®. None of those jet powered, radio alarm clock, blades up the wahzoo razors for your face. All you need is a Schick® Quattro®, which does the job and does it well with its four blades of awesome righteousness.

Are your ready to join the Schick® Quattro® #UnitedWeShave movement and take back summer for the clean-shaven?

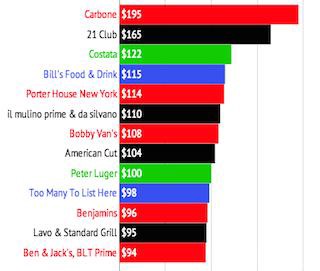

Steak Expensive

If you enjoy going to restaurants to order enormous slabs of meat cut from the flank of large animals that is then to left to rot (in a good way lol) for many days before being slapped under a flaming broiler, you have probably noticed something in recent months, as international demand for beef has intersected with drought that has ravaged cattle herds: It now seems “a bit like buying a diamond, doesn’t it? Well that’s the direction things are going in. During my years of reviewing steakhouses at Bloomberg News, I rarely spent less than $150 per person on any given visit. Enjoy your beef while you can afford it.” Or just cook it yourself.

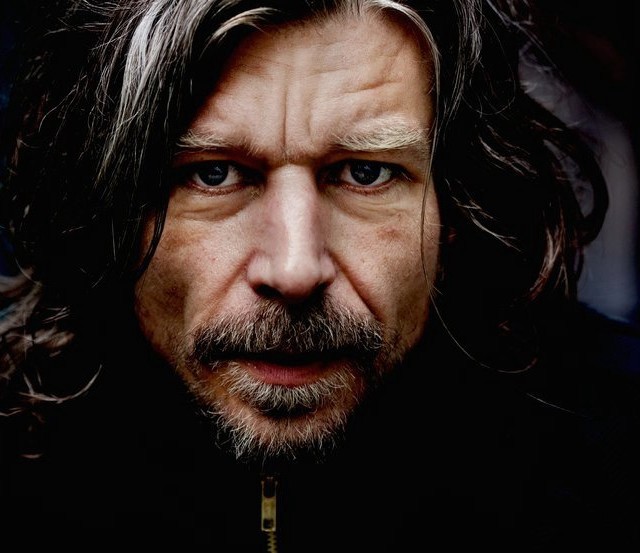

To Karl Ove Knausgård, Re: Your Tortured Feelings for the Gays

Dear Karl Ove,

I’m sorry it took me so long to get back to you, but as curious as I’ve been about your work, I had to overcome my suspicion and jealousy resulting from the onslaught of critical praise and (though I wish I could ignore such things) rock-star photographs of your L’Oreal hair and heavy smoking habit. In any case, with the understanding that the third volume of My Struggle (Boyhood Island) was recently published in the U.S., I just finally finished the first one (A Death in the Family). I have to admit, I was impressed by the opening section. Your meditation on the decay of a human body and the ensuing memory of the narrator (also “Karl Ove”) as a young, sensitive boy, who in the course of watching a news report sees a mysterious face emerge above a choppy sea, were mesmerizing. When, in the next scene, your father mockingly asks if you had seen Jesus, before telling you to forget about it, his aloof disregard of your excitement seems monstrous; in just a few pages, you had established the conflict of a lifetime, and I looked forward to being immersed in its slow resolution.

Granted, the next few hundred pages were not quite as exciting as you meandered between episodes of teen partying, heterosexual groping, and playing in bad cover bands, but the strategy is understandable: A 450-page book cannot always be on fire. Thankfully, you returned to form when, as an adult character, you took us to your grandmother’s house, where your father, having divorced and fallen on hard times, had been living in squalor before dying of a heart attack. Your unresolved anger toward him, along with your growing ambivalence for your older brother — whom you once revered — and your grandmother, an alcoholic who wavers in and out of sanity, was rendered with insight and, at moments, harrowing detail.

Karl Ove, in the spirit of honesty, I must tell you that, despite my genuine admiration for the above, I also had some real problems with this book that I would like to address with you now, with the hope that you (or perhaps one of the many reviewers who failed to bring this same concern to light) can respond to me. To put my objections in plain terms, your book made you seem like a bigoted, macho asshole — someone who on one hand purports to revere an entire roster of great homosexual artists and writers of the past century (but without ever mentioning their homosexuality), while on the other castigates homosexuality in a winking, assumed manner that has long been the bane of the worst kind of Hollywood movies. No surprise (since homophobia and misogyny are so often conjoined): Your understanding of gender seems equally rigid, and made me wonder if you are aware that not everyone falls into the same Tarzan/Jane dichotomy with which you view the world, and are all that much happier as a result.

Let’s take a look at a few of the offending passages I marked in the course of reading your book.

• “I could control myself. She had a nice body, but there was something boyish about her humor and manner that seemed to cancel out her breasts and hips.”

• “Nor could I ask [my friend] to open the bottle for me, that was too homo.”

• “I could open bottles with my teeth, perhaps it wouldn’t seem so homo.”

• “We never hugged. We weren’t the sort of guys who would hug.”

• “What was more important was that the embroidered blouse and the Sami shoes were not [my father]. And that he had slipped into this, entered this formless, uncertain, almost feminine world.”

• “He twisted his neck and patted some hair into place. He had always had that mannerism, but there was something about his shirt and those trousers, which were so profoundly alien to him, that suddenly made it seem effeminate.”

• “[Going to an adult video store] was incompatible with everything a normal life entailed, and most of those who went there were normal men…[but] I had no idea, this was foreign territory for me…”

•Even though the suitcase was heavy I carried it by the handle as I walked into the departure hall. I detested the tiny wheels, first of all because they were feminine, thus not worthy of a man, a man should carry, not roll. [Something I can’t find about the fear of sleeping in the same bed as your brother — as if you might wake up and find yourself fucking him — but at least having a separate duvet; this fear is similar to what we call “gay panic” in the United States, which still crops up now and again as a murder defense. “Your honor, that faggot winked at me and I had to kill him!”]

What’s remarkable about these passages, Karl Ove, is not that you hold such views (which, of course, are depressingly common), but that you seem to assume — since you show no contrition in relaying them — that your readers will understand and even condone them; that we will relate to you because we, too, want to live in a world of men who don’t kiss/hug/fuck other men and where all of the women have big breasts, wide hips, and live in “light, perfumed rooms” with “flowery wallpaper” and an “embroidered bedspread.” Let me be the first to say that I do not live in this world, nor would I ever want to; moreover, I find it seriously upsetting and demoralizing (though not exactly surprising) that someone like you, who does, has been the toast of the literary establishment.

Karl Ove, I was discussing my reservations about you with a former friend of mine, a non-homosexual (and BIG fan of yours), who said that I was being “too sensitive,” given that some of these scenes — notably the ridiculous bottle-opening one (which for the record I have done myself, even though I regularly enjoy homosexual relations) — occurred when you were an ignorant teenager. My response to this kind of argument is that you didn’t write the book as a teenager, and — as far as I can tell — you made no attempt to disavow or explain or even layer any of your language as an adult. You didn’t, for example, say, “Nor could I ask [my friend] to open the bottle for me, that was too homo, which in my uneducated state was the worst thing you could be.” Nor did my ex-friend have any response to my point about how many of the other passages reflected the thinking of the “adult” Karl Ove, as opposed to the adolescent one. This same ex-friend also told me that before I could criticize you, I “needed” to read Volume II — A Man in Love — because apparently there’s a scene where you express remorse about your inability to kick down the door behind which your pregnant wife is trapped (meaning you’re not as “manly” as you once thought) and your regrets about the “feminizing” aspects of child-rearing (similar to the suitcase/wheels problem, I guess). Also because you get a foot massage from another (male) writer or something. I don’t know, Karl Ove, I don’t really see how any of this bolsters your case; to the contrary, it seems to reinforce archaic views about the “traditional” roles of men and women, all of which were pretty happily discarded circa 1972 with the release of Free To Be You and Me (which, btw, I highly recommend for you.) Granted, we may have taken a few steps back since that golden era of first-wave feminism and sexual liberation (there was the whole AIDS thing too), but literature — unless you see yourself as the next Ayn Rand — should tear down the walls that constrain us, not reinforce them. (At least as I see it.) Like every non-heterosexual, I take enough abuse as it is, Karl Ove: I don’t need to suffer through 600 more pages of you whispering your kneejerk, hateful, conservative bullshit into my thoughts to offer my opinion.

If your book were just marked by homophobia, I wouldn’t really care; I mean, there are ten thousand similar books and movies and television commercials and news reports to get angry about every day. What’s most offensive — and frankly, disturbing — is the juxtaposition of your anti-homo remarks with the name-droppy admiration of homosexual artists. You tell us you “imbibed” Proust; you discuss Genet, Visconti, Rimbaud, Foucault, Frankie Goes To Hollywood (lol), but without ever discussing the fact that any of these artists were gay, or how their homosexuality influenced you. Karl Ove, you cannot seriously expect a homosexual like me (and you may be surprised to know that there are literally millions of us around the world!) to read so much unacknowledged name-dropping of my people without taking offense, can you? What you are doing is effectively appropriating — even annexing — a tradition to which you do not belong, for your own mercenary purposes. By all means, talk about Proust and all, but don’t completely ignore the fact that they’re gay; it makes you look stupid or possibly worse, given your fear of “homos.” Do you see the hypocrisy in what you’ve done here? It’s really no different than if you had written (after lauding the work of, say, Ralph Ellison and Zora Neale Hurston), “I don’t like hip hop, because it’s darky music.”

Karl Ove, there is a regrettable record of homophobia in the modern literary era: You can either recognize in yourself and then espouse these increasingly archaic (if entrenched) views or reject them; at the moment, I have no reason to believe that you would choose the latter, more honorable (and literary, in the best sense) route. Instead, you seem to have taken a position more akin to another European sensation, Milan Kundera, who just a few years ago in a collection of essays called The Curtain went on record, while discussing Proust, as a fellow homo-hater: “I myself lost the privilege of that lovely ignorance,” he wrote, “when I heard it said that Albertine was inspired by a man, a man Proust was in love with. But what are they talking about! …. [O]nce I’d been told that her model was a man that useless information was lodged in my head…. A male had slipped between me and Albertine, he was scrambling her image, undermining her femininity. One minute I would see her with pretty breasts, the next with a flat chest, and every now and then a mustache would appear on the delicate skin of her face.” He concludes: “They killed my Albertine,” without specifying who “they” are. (Although I am happy to be included among their ranks.) Milan Kundera could not be more wrong about Proust, Karl Ove, and given your failure to acknowledge Proust’s homosexuality — in spirit or style — you are walking in Kundera’s ignorant shadow. You can’t have it both ways: either embrace the enlightened world or reject it.

On the subject of Proust, there are some other things I’d like to say, given that his work — at least on the surface — seems to provide a template for yours, which is something many shallow-minded reviewers have picked up on in the course of relentlessly comparing you to the French master. True enough, like Proust, you have written hundreds of thousands of words that include many autobiographical memories — with the ocean scene clearly designed to function as a kind of madeleine (although it lacks the “involuntaire” quality of Proust’s most famous memoire) — and some lengthy philosophical digressions that probably fall safely under the “Proustian” umbrella. Like him, you have even reordered the events of your life in manner to make them seem almost fated, as if they were meant to happen, meaning that you — and we, your readers — can (in theory) achieve some insight and understanding about our lives from the artistic examination of yours.

But Proust represents much more than a torrent of memory; though you completely fail to mention this, he was foremost a homosexual novelist (itals mine, because “pride”) who helped to establish what must be understood as a homosexual tradition, in much the same way that, say, Toni Morrison is regarded as an African-American writer (and is all the more important to the tapestry of great literature for this reason; I’m sorry if this sounds like “Diversity and Literature 101,” but it’s time you knew that gays were recognized in this class). For Proust, his attraction to men helped to define an aesthetic viewpoint or “style” that infuses his work; true, he spends much time discussing homosexuality in the most vile terms, but this a Proustian trick. Because of the culture in which he lived — possibly even more homophobic than ours, at least outside of the literary establishment — he chose to express an overwrought, exaggerated, and, at times, almost campy abhorrence for homosexuality as a means to discuss it (relatively) openly, which — along with the transformation of (some of) his memories into a work of art — is the great theme of his work. Think of his obvious admiration for the brilliant but tragic masochist Baron de Charlus, or the short section on closeted men in Sodom and Gomorrah, which remains one of the most exhilarating pieces of gay writing ever put to the page; even a century later, it’s a more accurate description of the truth of our society — and the underlying despair felt by so many non-heterosexuals — than the news photographs of the happy gay couples getting married at the courthouse. (Not that I have anything against marriage equality: I myself am married to a man.)

This question of Proustian/homosexual style is not a small one in relation to your book, Karl Ove, given that you are not shy about expressing some interesting opinions on that very subject, which, at least as I see it, do not square with your interest in Proust. You state, “writers with a strong style often write bad books.” While you don’t specify exactly where you view Proust on this spectrum, I think 99 percent of the reading public would agree — whether or not they enjoy his work — that Proust had a very strong style; in fact, we might even go further and say that he had a very “gay” style; his prose — like so many great gay writers (and artists) who have followed in his wake — is expansive, oneiric, and ornate as he expounds on thoughts and feelings in a language as complex, nuanced, and frankly beautiful as the ideas he conveys, with sentences sometimes lasting for pages, broken up only by commas and dashes. (Unlike Stephen King, Marcel Proust is not afraid of “unmanly” adverbs.) The outlandish beauty of his prose must be considered a facet or element of his homosexuality; like so many who are scorned by conventional society, he retreated into his own world, where his God was Art.

By the same token, you seem to imply that your book is “good” because it lacks style. I mean, you didn’t say, “writers with a strong style often write bad books, as you can see here.” The problem here, Karl Ove, is that your logic is once again specious; like every writer, you have a style, it’s just that yours, except for the few scenes such as the ones noted above, is one marked by perfunctory observation — “She had fantastic eyes [period]” — clichés like “fat as a barrel,” (twice!) “lay of the land,” “eggs in one basket,” “I got into hot water,” “head over heels,” “the drop of a hat,” and so on, interrupted here and there with a long-winded, convoluted lecture, such as when you explain why all of the paintings you like were made before the 1900s, “within the artistic paradigm that always retained some reference to visible reality.” (I realize I’m criticizing a translation, but my understanding is that the effect is similar in Norwegian.)

My point is that you have a style, Karl Ove, which — unlike that of Proust, for example — is ill-suited for many of the topics you describe. Life is often complicated, which is why it requires complicated language to dissect it, whereas great art may or may not be simple, but good criticism never relies on pretentious Orwellian/corporate doublespeak like “artistic paradigm.” I often wished that your approach could be “inverted” (to use a very loaded Proustian term); for example, I would have been much more pleased if you had told me that a particular painting was fantastic and that your wife’s eyes had established a new artistic paradigm. Where your actually-quite-strong but cliché-ridden style really inhibits you is in the arena of love. “For Hanne,” you write about a high school crush, “I was a nobody and would remain so. For me, she was everything…. I wanted to see her all the time, be with her all the time, to be invited to her house, to meet her parents, go out with her friends, go on holiday with her, take her home…. “ Then a subsequent conversation with your mother about this same girl: “I’m in love,” you say, before unleashing yet another cliché, “Hook, line, and sinker.”

I hate to be so critical about a topic as sensitive as teen love, but it’s arrogant to think that such a banal description offers any insight to your readers; as a result, I kept wondering if you were trying to dupe us into thinking that you have suffered when you have not. Nor does it help when later in the book you offhandedly mention your adolescent resemblance to the Swedish actor Björn Johan Andrésen, aka “the most beautiful boy in the world” after he was cast by Luchino Visconti as Tadzio in Death in Venice (a visual masterpiece of unrequited and forbidden homosexual love, and an almost-perfect adaptation of the book about the same topic by the great German non-heterosexual Thomas Mann). Karl Ove, I hope you understand me when I say that straight, white boys who look like teen idols generally must make a more nuanced case for unrequited love than you have done here. Nor did your descriptions of love in this book make me want to jump into 600 pages of A Man in Love; there are limits to my masochism.) I would rather think about Proust’s (or, really, his narrator’s) adolescent infatuation with Gilberte Swann — the prelude for his even greater infatuation with Albertine — and how thrilling it was for both him and his readers when he first glimpses her behind the flowering hawthorns, and how he subsequently pursues her, all rendered in exquisite, operatic detail, because she is essentially someone he views, at least initially, as unobtainable.

I was informed by my ex-friend that you, in interviews, have described yourself as the “anti-Proust,” which perhaps would make some of my objections meaningless, except for the fact that you make no such claim in the book itself. You didn’t say, for example, “I imbibed Proust and then decided to disgorge six volumes of tedious, banal, cliché-ridden un-Proustian prose, effectively making me the anti-Proust.” Instead, you name-dropped about ten other gays and then slyly referenced your fear of homos. You have given me a new dream, Karl Ove, and it is to be the anti-Knausgaard, someone capable of discussing the artists I love without stripping them of what made their art (and their lives) compelling.

You are younger than Milan Kundera, Karl Ove, which is why I still have hope for you, and why I want to assure you that there’s another way. Granted, you can’t rewrite what you’ve already published, but perhaps you can make amends going forward; you can issue an apology or offer to make amends or reparations. You are now a rich man: There are plenty of nonprofits devoted to helping gay and transgendered teens to whom you could donate a small percentage of your profits. These are kids who genuinely struggle, but — if they don’t literally get killed — are often resilient. Next time you’re in New York City, we can take a walk along the Christopher Street piers, where I can introduce you to this world, which is so different than the one described in your book. At the very least, you can write for a future that recognizes humanity instead of belittling it.

I recently finished a novel that wasn’t nearly as popular as yours, but it filled me with hope. It’s called The Autobiography of Daniel J. Isengart and was written — in the manner of Gertrude Stein’s similarly titled novel about Alice B. Toklas — by an artist named Filip Noterdaeme, a New Yorker, by way of Belgium. Like you, Noterdaeme offers many memories of his life, in his case describing New York City during the 1990s and 2000s, where he and Isengart lived and worked. Isengart is a cabaret performer, equally comfortable singing in the guise of Marlene Dietrich as Elvis Presley (he creates a show called “The Importance of Being Elvis,” a reference to the Oscar Wilde play, in case that wasn’t clear). Both Isengart and Noterdaeme are obsessed with acknowledging the history of art in their own work, albeit in what is often a surreal or absurd manner. (Noterdaeme makes paintings called “Egg on Schiele” and “Francis Bacon with Extra Bacon.”)

Noterdaeme, who is a denizen (and critic) of the art world, where he works for many years in gift shops and giving tours, becomes disillusioned by the corporate expansion of New York City museums in the 1990s and eventually starts his own — The Homeless Museum of Art (or HOMU) — which he and Isengart set up in their apartment. Like so many museums, theirs possesses a complex bureaucracy, complete with a Staff and Security Department (housed in their bedroom), a Membership Department (with forms stored in the freezer, instructing members to pay their fees to the homeless), and so on. He also writes “open letters” to his fellow artists and museum directors, much in the way I am now writing to you.

Like you, Noterdaeme sometimes employs lists, except he always delivers his with at least a few words of context. “[T]he homeless,” he writes, when considering the concept for his museum, “were more dramatic than Hannah Wilke, more Zen than John Cage, more happenstance than Alan Kaprow, more cunning than Andy Warhol, more vulgar than Jeff Koons, more abstract than Ad Reinhardt, more thrifty than Joseph Cornell, more repetitive than Daniel Buren, more preachy than Barbara Kruger, more obsessive than Louise Borgeois, more angry than Penny Arcade, more foul than Paul McCarthy, more banal than Julien Schnabel, more rigid than Martha Graham, and more manipulative than Lars von Trier.”

Perhaps you can see how much more effective this list is than your many eye-rolling lists of bands and books: “I had been listening to bands like The Clash, The Police, The Specials, Teardrop Explodes, The Cure, Joy Division, New Order, Echo & the Bunnymen, The Chameleons, Simple Minds, Ultravox, The Aller Værste, Talking Heads, The B52s, PiL, David Bowie, The Psychedelic Furs, Iggy Pop, and the Velvet Underground.” Or how as a student you read, “Adorno… some pages of Benjamin… Blanchot for a few days… a look at Derrida and Foucault… a go at Kristeva, Lacan, Deleuze, while poems by [wtf, ELEVEN poets] floated around,” or the books in your office: “Paracelsus, Basileios, Lucretius, Thomas Browne, Olof Rudbeck, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Albertus Seba, Werner Heisenberg, Raymond Russell, and the Bible, of course, and works about national romanticism and about curiosity cabinets, Altantis, Albrecht Durer and Max Ernst, the Baroque and Gothic periods, nuclear physics and weapons of mass destruction, about forests and science in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.”

As readers, we might not be on intimate terms with every one of the artists mentioned by Filip Noterdaeme, but even if we’re not, we appreciate his wit; he is not just offering names. Thus he remains on solid footing whether discussing his hero, Marcel Broodthaers, or his “careerist” enemy, Marina Abramovic. (“The Museum of Modern Art could be renamed the Museum of Marina Abramovic” he says at one point, after his friend Penny Arcade notes that Abramovic’s most famous show, in which she sat across from people and stared at them, should have been titled “The Artist Is There” instead of the “The Artist Is Here.”)

The book isn’t all laughs: like you, Filip Noterdaeme recognizes the importance of being the historian of his own life (to borrow a phrase from the great homo writer J.R. Ackerley); he just renders his memories in a more enlightened manner. He seeks out the strange and the unconventional, which is so often the basis for great art, because it challenges us to see things in a new way. He celebrates individuality instead of constraining it.

Noterdaeme knows that his fight is a difficult one, and we sense that he’s probably doomed to exist on the fringes of the world (at least as it exists now), but as readers, we appreciate his fight. Near the end of the book, Noterdaeme and Isengart take jobs guiding German tourists from their hotel to MoMA. “When I saw Filip Noterdaeme, the director of the Homeless Museum of Art, an as yet insufficiently known institution of which he is the founder, stand outside in the cold for two hours in a cheap rented tuxedo and holding up a signpost pointing towards the Museum of Modern Art, I must confess I began to cry.” (Remember, this is Noterdaeme writing in the first person as Isengart.)

Here is another “struggle,” one defined by a man’s search for artistic identity. “I have not… survived in New York for 20 years to become a human signpost,” he says late in the book before resolving to keep his museum open, regardless of its popularity, and soon after finds himself talking to hundreds of New Yorkers (or tourists) who make their way past his booth at the High Line, engaging these passersby in a way that feels important for the future of art, as he breaks down the walls of the traditional, corporate museum. “In short,” Noterdaeme writes about himself, “he learned the art of losing himself without getting lost.”

It’s an art of honest engagement with yourself and others that you, Karl Ove, would do well to emulate.

Sincerely yours,

Matthew Gallaway

New York City, July 9, 2014

★★★ Morning was sweaty without being hot. Across what had earlier been blue sky, a solid strip of gray had formed, seeming to match the width and position of Manhattan. It stayed there for quite a while. By afternoon, it was gone, and the air was less damp and more pleasant — too pleasant, in fact, to help bake off the effects of the air conditioning when one fled to the fire escape. The gentle breezes were the answer to some unrelated problem. The clouds came back, to gather into dramatic late-day compositions of slate and ivory and rose. One ray of light broke through to light up one street corner, in golden isolation.

Beauty and Ruin in Pigeon Forge

by Sam Worley

In May, Dolly Parton returned from promoting her new album, Blue Smoke, to Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, for the celebration she hosts every year: the Dollywood Homecoming Parade. Thousands gathered along the stretch of U.S. Route 441 known as Dolly Parton Parkway, from stoplight number six to stoplight number three. The devoted sat in strategically placed lawn chairs; the less eager watched from roadside hotel balconies. My boyfriend and I stood in the median of the parkway, opposite a spiraling bumper-car attraction, and watched as the first few floats passed: veterans, students, and an official contingent from the City of Pigeon Forge. A marching band played “9 to 5” and then “Islands in the Stream.”

Then, there she was: a bright yellow flare in the distance, her arrival prefigured by ranks of superfans moving up the side of the road, wearing matching T-shirts. Dolly, in a button-up yellow minidress, braided blonde wig, and long red claws, advanced into the foreground atop a float advertising the FireChaser Express, a firetruck-themed roller coaster at her amusement park, Dollywood, a few miles up the road. “Hi, Dolly!” people called up at her. Cops and bodyguards walked alongside. She waved and passed. The parade went on. The next float was a giant horse’s head rising from an American flag — another ad, for Dixie Stampede, Dolly’s four-course dinner theater.

The Dollywood parade is the centerpiece of a new book, Pilgrimage to Dollywood: A Country Music Road Trip through Tennessee, by Helen Morales, a classics professor at the University of California–Santa Barbara and a lifelong Dolly Parton superfan. Morales’s father was a Greek Cypriot immigrant to the U.K., where he ran a restaurant; he told her when she was a child that Parton’s music, much of it rooted in an experience of poverty and a determination to overcome obstacle, was “our music.” Because she felt then like an outsider, Morales took solace from the Parton oeuvre:

I would often feel, to quote the lyrics of Dolly Parton’s song “Fish out of Water,” like “they’re caviar and you’re fish sticks.” (It was a while before someone explained to me that “fish sticks” is American for “fish fingers.”)

Morales isn’t a critic, just an effervescent observer, and a delightful, slightly goofy narrator. She writes more to satisfy herself than with any particular thesis. In Pilgrimage, a sort of travelogue, Morales flies her family to Memphis before they sweep eastward to Pigeon Forge, with Morales offering various observations along the way, ranging from the deeply banal (“To think about Elvis is to think about America: its history and its values”) to the totally interesting, like when she locates roots of the phrase “white trash” in a series of old pseudoscientific research called Eugenic Family Studies, which sought to prove that poor white people were inferior due to mixed-race ancestry.

Morales is moved by a general dissatisfaction with Santa Barbara, which she finds too sunny, too shiny — “where quinoa is considered a food group, and camping a moral imperative.” Funny, then, that she would latch onto Dolly Parton, who projects an undimmed sunniness — although Parton is distinct from California insofar as in California, the sun is real. But Morales believes that there is something meaningful beneath the facade, or perhaps because of it. Parton’s visual aesthetic isn’t separate from her music, her lyrics, or her various business concerns — an early practitioner in the fine art of image management, she’s constructed the whole package work to her favor, while still maintaining an aura of relatability. “My image get in my way?” Parton once said in response to an interviewer’s question. “Ya gotta be crazy. It’s my image that gets me most everything I want. I created the whole thing.”

Parton’s skill at being many things to many people accounts for the diversity of her fan base, capacious enough to hold drag queens and the sorts of hard-core emotional supplicants depicted in the documentary For the Love of Dolly, as well as the more mainstream country fans who surrounded us at her parade, which kept going long after Parton had fled the scene. There were county-fair beauty queens, classic cars, and young girls dressed up like porcelain dolls — a distillation of the Parton look, at least, if not the spirit of the overall Parton endeavor. But even this was an eclectic affair. There was a van advertising Parrot Mountain and Gardens: “See, Touch and Feed God’s Beautiful Tropical Birds.” There was a fake country church, and a real church congregation, on top of a trailer. There was a guy dressed as Batman, who shouted at the crowd and waved: “How y’all doin’!”

Farther down the road from the parade, straddling the border of Tennessee and North Carolina, was the entrance to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, one of the eastern U.S.’s premier natural attractions. You can tell it used to be pretty there, all rolling hills and pristine woodlands; in a sense it still is, but in the gauche, unchecked way of Las Vegas. Opportunities for wholesome recreation abound on Route 441: a knife museum; zip lines; helicopter rides; the Parton Family Wedding Chapel & Antiques; the World’s Largest As Seen on TV Superstore; WonderWorks, an upside-down building which also serves as a liftoff site for hot-air balloons; a Titanic-shaped Titanic museum, the cousin of a similar attraction in Branson, Missouri; and a Mount Rushmore replica engraved with the faces of John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Charlie Chaplin, and Elvis Presley. A Ferris wheel turns behind the Parkway. A chimney in front of a barbecue restaurant sprays steam meant to mimic smoke.

Pigeon Forge was not a singular product of Parton’s success — it had long been a weird, plastic tourist mecca when, in 1986, she became a co-owner of Silver Dollar City, the prior theme park, and reshaped it in her image. The town was established by white settlers in Sevier County along the floodplain of the Little Pigeon River, which runs through it. The other part of the name refers to a short-lived iron forgery; because of limited avenues for transporting iron out of the region, and some deficiencies in the local ore, the industry that emerged in the nineteenth century was subsistence farming, though other business opportunities became available too. Neighboring Cocke County is famous for its moonshine, an industry that boomed in response to the transportation problem: It was much more profitable to move corn out of the area as liquor than as cobs and kernels.

Parton’s family had roots elsewhere in the Great Smoky Mountains, but moved to Sevier County when locals were displaced to make way for the national park, which opened in 1940. Because it was envisioned as a natural reserve, the people who lived on the land were bought out, or forced out by eminent domain, in the largest such removal in Park Service history — more than a thousand families all told. The opening of the national park began a decades-long tourist boom that was abetted in the nineteen fifties by the construction of U.S. Route 441; as nearby Gatlinburg, located at the park’s gates, became saturated, development began to snake up along the highway. By 1963, the Pigeon Forge City Council had passed an ordinance banning livestock odors on the grounds they would be “offensive to the citizens and visitors of the city.” Today, Dollywood is the largest employer in Sevier County.

After the parade, we camped several miles away at the headwaters of the Douglas Dam, a Tennessee Valley Authority project completed in record speed to produce hydropower for metal production during World War II. On the map, Douglas Lake looks like a snake that’s been run over by a car, spindly and bulging, with tiny branches trickling off on every side. The land slips so smoothly into this seventy-year-old body of water that you are moved to imagine the terrain beneath it. The many reservoirs that have replaced valleys throughout the South (we stayed at another, in eastern Kentucky, the following night) are a weird counterpoint to the way sites like Pigeon Forge operate, as places that look natural — water, shoreline — but aren’t. The construction of Douglas Dam flooded the fertile fields at the bottom of the valley, on the shores of the French Broad River; this too, in the bashful language of a 1958 study, “necessitated considerable adjustment of the population.” One hundred and eighty families were forced out, part of a larger wave of southerners headed elsewhere. “In recent years,” that same paper noted, “the paved highway, the automobile, and the radio have opened up one mountain fastness after another.”

It’s hard to conceive what this all must look like through Parton’s eyes. She was born in 1946 in a house that’s said to be back in these hills somewhere, though Morales, for one, wasn’t able to find it, and afterward she felt “prurient” for having looked. In any case, there’s a replica at Dollywood and there are, in the national park, a few remnants of prior settlement displayed as historical attractions. In a pretty excellent burn, a 2000 article on vernacular architecture and country music by Michael Ann Williams and Larry Morrissey argued that the Dollywood version “achieves something the National Park Service typically fails to do: it gives the tourist a feel for how the house was lived in.” Unlike the park’s well-preserved specimens, the Dollywood house is cluttered, looks well used, and was arranged based on memories offered by the Parton family.

As Morales points out, an irony occurs at the intersection of Parton’s lyrics, which idealize pastoral living and denigrate the grind of the city, and the reality of Pigeon Forge, a place that Parton has had a hand in shaping, which also idealizes the pastoral, sort of, albeit within the context of being a very large strip mall. “Why not put a Titanic museum in the Appalachian foothills?” somebody once asked.

Dollywood itself actually figures into Pilgrimage quietly; it comes last, after Morales and family have visited the Smoky Mountains and found them unsatisfying. “I am aware of the irony that the packaged nature of the amusement park was more pleasurable (for us) than the oppressive experience of unrelieved forest in the national park,” writes Morales, sounding like she’s finally having the authentic American experience she was looking for. The theme park features rides and junk food, some quiet oases, and at least one thing that sounds truly stunning: a thirty-thousand-square-foot bald eagle sanctuary. Somehow the unifying narrative is Parton’s rags-to-riches story. But the park inspires Morales, at the end of her book, in a cinematically cheesy moment. She feels good about Dollywood, she feels better about America: “Through its omissions as well as its attractions, Dollywood helped me see the dream country to which I can be loyal. In that sense, I suppose, I did what Dolly Parton tells us to do in her refrain at Dollywood to ‘celebrate the dreamer in you.’” Amid the hubbub, she offers a silent thank-you to Parton.

This kind of emotional encouragement isn’t cheap — admission to Dollywood is fifty-eight dollars. We didn’t go. But we stayed at the parade for a long time. The Sons of Confederate Veterans came along, waving their flag, followed by Santa Claus sitting on the back of a tinseled flatbed truck. There were many antique tractors; there were many more majorettes. One of them stopped in the middle of the parade — everybody else kept moving — and gestured skyward, as if there was something there. Nobody paid attention. The parade went on. Finally somebody looked up, and then we all did. There was a rainbow directly overhead, though the sky was mostly blue and there had been no rain. “Dolly brought it — that’s the truth,” a woman standing in front of us said.

Samuel Worley is a freelance writer and editor in Ohio.

Photo by Jen

Introducing... Shirterate

People often ask us what’s next for our company. We’ve spent a lot of time surveying the Internet landscape, and, while the land rush into the content arena has been gratifying to watch for those of us who’ve worked in the “space” since long before there was a venture capital invasion, we really feel that the future of the Internet is in serving individuals. One by one. Artisanally. Particularly high net worth individuals. So we’d like to invite you to visit our new project, Shirterate.

A Poem by Maureen Miller

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Voices from the Field

He reigns over me like a meadowlark in the meadowlands.

Underground wiretap. They buried my heart under the stadium stands.

Some of us have to work for a living. Saviour, my sin, my paisan!

Pobody,not even the nerfect,has a fetish for his peeling calloused hands.

He sticks it in me with his workman’s hands.

I want a man with a ruddy tinted hand.

I want a man with a slowhand.

Do you venerate your dad?

Who watches Watchung Avenue?

My prayer hands fuss Holstein Manti mantilla.

Squawkbox mezzo soprano while I kneel at altar rail bands.

My turnpike binoculars see the ancestral homeland tenements. Semper sperans.

Montclair as Mont Blanc (poem), but with Parker pens.

But listen to your side stitch. Don’t write poetry.

The hand that rocked me slapped me out that sleep.

The money’s in spec screenplays. You can’t eat your spikes, sweets.

You steeplechase with bench-pressed Princetons who thought they hit a triple jump heat.

Born meters in, methinks I hit a puddle for the entrance fee.

I want his times vetted by Brenda Patimkin’s surgeon, man.

Ali MacGraw didn’t need a rhinoplasty to look ethnic cool.

No chest, though. Some Weehawken loonie must have done her.

I’mma do me in milky bucks and madras sew.

Spike Lee in a knickerbocker get-up.

Forty machers and Abdul.

My old man reneged the two-state solution.

Then I jumped in the duck pond of the office pool.

Cogsworth is the voiceover and the basso is the treble.

Have you ever clicked with your boomtowns on that borderline level?

I split Penn Relays rods-worth on your clever little bevel.

Something Neptune dipshits with the integrated hipsters but the version by Manfred Mann.

This shore doc says “I got this” looking hella like Dukakis and the pediatrician gave me a ride.

Something something opposite of the devil.

The ridge where I come from is a small town.

I wish I could step off that ridge, my friend.

Think Short Hills Mall. They use small words.

They release birds. The means justify the ends.

But not me! A broad’s as good as what she does for me.

A passable wifey’s better than the fastest wi-fi via broadband.

Your turncoat Audubon binoculars needn’t tell my binaca to knock it off.

You have a tight box. Make some calls.

Keep my hundred dolla bill when I’d no change from Ras Baraka.

What’s your old man’s retirement plan?

Spike Lee in a Knickerbocker get-up.

Forty machers and Abdul.

Gentrification. Loathsome.

Then I jumped in the duck pond of the actuarial pool.

Maureen Miller, M.D. M.P.H. (doctorwritermaureenmiller.tumblr.com) is a medical resident in anatomic and clinical pathology and a founding editor of Rap Genius (www.rapgenius.com/momilli). Her research focuses on environmental origins of chronic disease in low-income urban neighborhoods and Vampire Weekend.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Death of a Mr. Dream

by Kevin Lincoln

The first Mr. Dream show was on Halloween night, 2008 in a New York City apartment.

Adam Moerder, Matt Morello, and Nick Sylvester dressed up as Dhalsim from Street Fighter, Daniel Day-Lewis and “the Karate Kid [after] letting himself go (concept costume),” respectively, and played to a room that included “two furious girls who kept trying to dance and failing, since you can’t really dance to a band that sounds like Nirvana, or the Wipers.” Over the next five years the band would go on to release a few EPs and an LP; tour with Archers of Loaf, Sleigh Bells, CSS, and Cloud Nothings; and sing in the chorus at LCD Soundsystem’s final show.

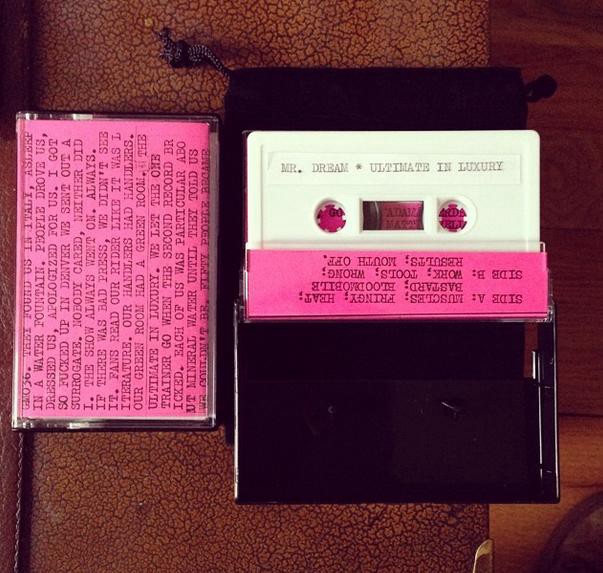

On Monday, the band released its final, posthumous album, “Ultimate In Luxury,” which you can stream here. Sylvester and Moerder are both friends, so I reached out to do a little postmortem for Mr. Dream and the handful of scorched-earth punk records they left behind.

So tell me about the birth of Mr. Dream. You two have known each other since college, right? What led to starting the band?

Nick Sylvester: Five years ago I would have said something like “pure and utter disgust for chillwave.” The truth is more banal. I knew Adam from the Lampoon, and I knew Matt through a mutual friend named Win Ruml. The three of us were all looking to make music at around the same time in 2008. We went to a Jay Reatard show together at Europa and knew that was the kind of music we needed to be making: something loud and fast and stripped down. It looked like a lot of fun to play that kind of music.

I would describe Mr. Dream’s music as sort of hyperkinetic lit-punk, or like, the sound of pissed-off New Yorkers playing music that sounds like F-18s. Please improve on this description.

NS: That was always the blessing and the curse of this band. People heard we went to Harvard or wrote for Pitchfork and assumed the music was much more deliberate than it actually was. I don’t recall any literary references in any of our songs.

AM: I like to think that Mr. Dream’s sound predicted the pummeling rage and anguish one finds on Twitter.com every day.

Though I’d read your music writing before I’d met you, this is the first band I know of that you two were in. How long have you guys been playing?

NS: I played trumpet in a wedding band called the Stu Weitz Orchestra. We had one or two gigs every weekend around Philly. I also played trumpet in the Matt Turowski Jazz Explosion. This is how I paid for high school. In college, I was in a band called Forced Premise with a bunch of Lampoon people: Simon Rich, Rob Dubbin, Colin Jost, and sometimes our friend Matt LeMay. He was an honorary member.

Adam Moerder: I was in a grunge band in high school, but we never made it further than the high school talent show circuit. The band was called Scorched Earth and we had a rule to always perform in our pajamas.

NS: This is the first time I’m hearing about the pajamas.

How’d the band go about writing songs?

NS: We all tried to bring in rough ideas, but it was usually Adam who brought in the strongest ones and stitched the songs together. I learned so much about songwriting from him. He might be my favorite rock songwriter — which made producing these records so difficult and emotionally complicated. I didn’t know what I was doing, and I didn’t want to fuck anything up. Our first EP was the first time I ever recorded or mixed anything and I made all kinds of stupid mistakes. So the kind of sound we were looking for changed as I learned new tricks and got better at listening. There aren’t many bands I know of whose production gets better with each successive record — certainly not in such a pronounced and obvious way.

Why’d you guys decide to end the band?

AM: There was this big swath of music we loved that wouldn’t have worked in the context of Mr. Dream. We wanted to branch out, but felt restricted by how a Mr. Dream song was “supposed to sound.” Plus we were gradually becoming not terrible at our instruments, which opened up a lot of possibilities.

Nick, how did the evolution of your record label, Godmode, coincide with the lifespan of Mr. Dream?

NS: Godmode was a vanity label for Mr. Dream releases. In 2011, I started doing more production work outside the band, and one of the acts I worked with was YVETTE. We did a 7” together (Matt LeMay co-produced), and not a single label we approached would put it out. I couldn’t believe it. I had just assumed all great bands find a home somewhere eventually. Not the case. I decided to make Godmode more of a real thing and put out the record.

AM: I don’t have an official title on the label (other than Montreal Sex Machine and FITNESS member), but I generally try to pitch in whenever possible, whether that’s listening to drafts of songs, loading in gear for a show, or buying some Red Bulls for Nick because he says it’s very important for the label that he has Red Bulls.

NS: We can work on an official title.

AM: “Riff technician.”

So why does Godmode release its music on cassettes?

NS: The process for making the music isn’t different, but the mindset is. I wrote about this for Pitchfork last year, you can read that here:

But there’s no format more human than the cassette. No format wears our stain better. I have not encountered a technology for recorded music whose physics are better suited for fostering the kind of deep and personal relationships people can have to music, and with each other through music. … No audio format keeps me more focused on listening to the thing itself, without the distraction of having a web browser right in front of me, without the baggage of an ersatz music news cycle, the context upon context, the games of the industry. Music released on cassettes doesn’t feel desperate or needy or Possibly Important. It tends not to be concerned about The Conversation. It resists other people’s meaning. That’s what I like about the cassette. It whittles down our interactions with music to something bare and essential: Two people, sometimes more, trying to feel slightly less alone.

One of my favorite touches about Godmode are the essays that you guys include with the cassettes, which are like abstract liner-notes. How’d that become a thing, and what do you guys like about it?

NS: I started doing this when I found out other tape labels were copying our style guide — right down to the type and stamp. It’s not exactly an original idea to use stamps — I ripped off Jon Galkin at DFA — but after I found out about this, I wanted to do something nobody else could replicate. The cover essays are a way to vibe a release and give the songs an emotional context.

AM: The packaging was a stroke of genius from Nick. The essays are my favorite, they really set the tone for each release. As a kid I remember being so excited to buy No Code, the Pearl Jam album, because the CD packaging included all these random polaroid pictures (one was an extreme close-up of Dennis Rodman’s eyeball). What does it all mean?! It created such a cool aura of mystery. While nothing on Godmode will ever measure up to the divine perfection of Pearl Jam, we’re at least standing on the shoulders of giants.

The Godmode family now includes Mr. Dream kindred-spirits Sleepies as well as artists completely different from your band, and each other, like Yvette, Fasano, and Shamir. What’s the pattern usually like of an artist ending up on Godmode?

NS: I’m trying to put together a good cocktail party. For me, that means playing personalities off one another. You end up approaching something like Shamir’s music in a very different way when it’s on a label with Yvette. The only hard rule for our crew is no assholes. I work with every artist really closely so I have to want to actually spend time with you.

Nick, what kind of trajectory do you see Godmode taking? How are you looking to expand and continue the label?

NS: It’s a new operation so there’s not much of a plan beyond doing more of what interests us and less of what doesn’t. I enjoy every aspect of Godmode. Everything from how we reply to press inquiries to how we do our distribution to how we do our books is an opportunity to do something special. As a producer I’m lucky: I get to choose what I want to work on, and feel as invested in the music as the artists do.

Adam, what are you interested in these days, making-music-wise? I feel like I read somewhere that you were sort of over, or frustrated with, guitars?

AM: Oh, I still love guitars, but I felt uncomfortable being pegged as a “rawk” guy. It’s like that Seinfeld episode where Jerry’s afraid to have a threesome and forever be known as an orgy guy…that lifestyle becomes you.

Enter MSM and FITNESS. With the former, Nick and I really wanted to capture a rock band attempting to make dance music and the rickety mess that ensues. It keeps getting compared to LCD Soundsystem, which is fair, but the inspiration mostly came from those Rolling Stones records where they tried to do disco.

FITNESS is mostly the result of me learning how to use synthesizers and drum machines. It’s a totally different writing process than anything else I’ve worked on, which is really refreshening. Basically the project was born when I first laid eyes on this album cover.

I remember you tweeted something about a Pitchfork interview with the band Posse and how it was cool that musicians were talking about their day-jobs now. You have a day job; Adam and I worked together at BuzzFeed right before I left, while Nick has done a bunch of interesting stuff outside of music. What has it been like balancing music with working, writing, etc.?

NS: I don’t think anybody deserves to make a living from music. If it happens, that’s great. But you can’t expect people to like what you do, let alone pay for it.

Kevin Lincoln is a writer living in Los Angeles.