Words Helpful for Once

“But let’s stop here and register the proper cautions and caveats: There has been no investigation, no conclusive proof. (And there won’t necessarily be a proper and convincing investigation, either, considering the deliberately chaotic and militarized state of eastern Ukraine these days, and Russia’s clear interests.) We shouldn’t pretend to know for certain what we don’t.” — Here is the moment at which you can tell that you’re reading the right piece, or at least not the wrong piece, about Ukraine, today. (Since publishing, the incriminating tapes mentioned have appeared online.)

Meanwhile, in the Void

Meanwhile, in the Void

Got to ‘smell’ outer space today when we opened the ISS hatch to the #Cygnus outer hatch. Smelled like wet clothes after rolling in snow.

— Reid Wiseman (@astro_reid) July 16, 2014

As the Earth prepared for one more round of chaos, an astronaut stopped to smell the hydrocarbons.

New York City, July 16, 2014

★★★★★ It was cool, utterly cool, under the gray morning. Was it getting brighter? Someone’s mirrored shades, approaching up the street, looked suddenly agleam. Downtown, a fresh wind was blowing down the subway steps. The puddle around the blocked drain on the landing, days old now, had dwindled by maybe half. There were white shoe prints in the black silt layer at the bottom. A cyclist pulled out into the bike lane on Lafayette without looking, forcing an oncoming rider on a Citi Bike to swerve and exclaim. The air felt nice on bare arms, in short sleeves. One’s own skin was skin, after all, with live nerves in it, something more than a thermoregulating membrane or a layer of waterproofing. By afternoon, the sun was out and shining down. Different cloud types overlayered one another, and warm eddies chased after cool ones. People played music out their car windows at a sociopathically solipsistic volume, the beats forcing their way through the crowded sidewalks, carrying around the corner and up the block. The dining hubbub at open-air tables reached restaurant-interior levels. During the walk home, the colors in the west seemed unusually dull and ugly, gray and a bleached dead off-yellow. From the apartment window, though, the tinted monochrome clouds had something going on with them after all, a photographic-plate quality, a bright amber-white scribble along the top of an undulating row of connected dark gray puffs, with more of that hot white coming up on their lower edge. Subtly, the white burned into the gray, veining it and then shredding it, and an orange light started burning up from below. Even as this developed, the sky a few handspans higher up remained pure indifferent daytime blue, with a milk-white contrail stretching fat and persistent across it and white cirrus above that, a swath of some other sky altogether. Between the high and the low a gray veil darkened into view, like the smoke of something dirty burning. Then the sun got into the gray and raised bright ripples on it, while the lower clouds darkened to inky cutouts. The smoky veil turned brilliant pink. Below it, along the horizon, ran a whole field of fine parallel lines of magenta and orange, with still some sky-blue lines running among them. Abruptly, the veil went dark again. Hot-coal reds showed behind it, and the stripes on the sky were now pink and purple. Then the brightness was gone, yet in the dull afterlight, the blankly silhouetted clouds were three-dimensional again, shaded and textured by a barely luminous brown.

Man Vs. Word

In 1969, a psychologist named G. Harry McLaughlin published the results of a number of experiments he’d made on speed readers in the Journal of Reading. His fastest subject was Miss L., “a university graduate with an IQ of 140” who had taken a speed reading course and claimed to have achieved speeds of sixteen thousand words per minute “with complete comprehension.” He hooked her up to the electro-oculograph, a device that measures eye movements, and let her rip.

Miss L. read Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust at 10,000 words per minute […] When she was half way through I asked her for a recall […] Miss L. recalled a number of details but only six [of twenty-four] main points. She did not mention the most crucial point of all, namely that the heroine was having an affair.

There is not much point in even opening A Handful of Dust if you aren’t going to twig to the fact that Brenda Last has betrayed her husband. Surely, nobody who has failed to catch the central premise of a book can be said to have “read” it. Woody Allen has an old and much-quoted joke along these lines: “I took a speed-reading course and read War and Peace in twenty minutes. It involves Russia.”

On the other hand, though, even the slowest, most deliberate reading is no guarantee of comprehension, a point my friend Ron once made at a long-ago lunch. I’d asked him, “So what are you reading these days?”

Descartes, he replied, with an abstracted air; he’d just finished, he said.

“How did you like it?”

“I read each word.”

Some weeks ago I was asked to try out a speed-reading phone app called Spritz: it’s one of a number of new products from tech startups that are trying to Disrupt Reading in one way or another. The tech writer Jim Pagels of Slate wrote approvingly of the Spritz-like Spreeder app last year, which he’d been using for the better part of a year. He says he’s been able to read a great deal more using it, and added, strikingly, “If only I’d known about [this] while in college, I may have actually gotten through all 1,000 pages of Tom Jones.” The slogan of Spritz, Inc. is: “Reading, reimagined”; their product makes use of a technology called Rapid Serial Visual Presentation, or RSVP, which more or less boils down to showing you one word, or a few words, at a time. The company claims that their spin on the technique can enable us to read more, read faster and/or retain more of what we read.

RSVP was invented in 1970 by Kenneth I. Forster, a researcher at the University of Arizona. Aside from offering researchers a precisely controlled means of investigating language processing, the system has long suggested certain potential advantages over conventional reading: it requires a high level of attentiveness as the stream of words scrolls by, permitting less wandering of the mind, and it also requires far less eye movement on the reader’s part than does conventional reading.

In the case of Spritz, no eye movement at all is required of the reader; exactly one word is displayed at a time, and each word appears with its “optimum recognition point” in the same spot, and colored in red, in order to aid focus.

I find it quite relaxing to read using Spritz, in a way; because your eyes don’t move, the words just flow by, in a curiously unimpeded manner. You can change the speed from very slow — ordinary reading speed is around two hundred and fifty words per minute — all the way up to a thousand words a minute, which whizzes by at such a rate that I have trouble catching more than the barest gist of each sentence.

But after a while spent practicing, I concluded that it is much more difficult to gather ideas of any complexity at all using Spritz than it is in ordinary reading. Complex ideas, like those routinely presented in philosophy or literary fiction, require a lot of rereading as you go. Also, when the sentence begins in a Spritz display, you can’t tell how long it’s going to be: a terrific drawback for comprehension. It would be nearly impossible to read a very ornate style of writing one word at a time — a style like Gibbon’s, say, or Proust’s — because the final clause of each sentence comes so long after the first that you’d be bound to lose track. (It wouldn’t work for poetry, either.)

I admit, I’m set in my ways to some degree: I can’t enjoy very dense prose properly on a tablet or Kindle either, not even after years of practice. I can’t situate my thoughts in the topography of a big book the same way when I’m able to see the text only through a keyhole, as it were, unable to feel with my hands whether I’m a third or a tenth of the way through; I feel as if I’m on the surface of the text, rather than in it. That hard, glossy surface!

This is in no way to suggest that I’m about to give up the ability to find all instances of the word “ilk” in Infinite Jest in under one second! (There’s just one, in the remarks of Madame Psychosis: “The endocrinologically malodorous of whatever ilk.”)

A romantic figure named Louis Émile Javal (b. 1839) played a big part in the development of speed reading. Javal, a Parisian ophthalmologist and inventor, came from a family much afflicted with strabismus and other eye troubles; he originated any number of ophthalmological devices and therapies, and named, though he was not the first to observe, the saccades (“jerks” or “twitches”) and “fixations” that characterize the eye’s uneven passage over written text. This discontinuous motion of the eye during reading appears to have been noted first by German physiologist Ewald Hering, who, in 1879, affixed a rubber tube to a cigar holder, put that in his ear, and, placing the other end of the tube on the edge of an open eyelid, found he could hear the jerking movements of the eye beneath as it read.

You can quite easily feel this movement yourself, as Javal’s associate M. Lamare discovered in the lab of the Sorbonne, right around the same time Hering made his observations. Just close one eye, rest your finger lightly on the closed eyelid, and read with your other eye; you’ll be able to feel a whole flurry of saccades. This realization, that the reading eye doesn’t focus smoothly on each letter or word, but instead gathers in whole phrases, skips around and backtracks as the mind figures out what’s being said, was key in the development of speed reading.

Ake W. Edfeldt focused on a different physiological aspect of reading, what’s now called “subvocalization,” which he described in a 1960 monograph called “Silent Speech and Silent Reading.” Using electromyographic sensors placed on the larynx, throat, and lips of his subjects, Edfeldt discovered that people bring the vocal apparatus into play as they read, in a kind of subliminal version of “sounding out” or reading aloud. Edfeldt found subvocalization more pronounced in unskilled readers, but even skilled ones frequently employ it in reading particularly difficult passages.

In the early sixties, a Salt Lake City teacher named Evelyn Wood began teaching enhanced reading techniques based on her own observations, and an interest in “speed reading” came into the mainstream. The key goals of Woods’s method were to eliminate subvocalization, and to reduce eye movement as much as possible by training the eye to flow straight down the page rather than going line by line; simultaneously, the hand sweeps down each page as a guide. This system became very popular; Presidents Kennedy and Nixon invited Wood to make presentations to their respective staffs, and in 1977, President Carter and his family took the Evelyn Wood course, as well. You can still buy the The Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics Complete System online (“a comprehensive multimedia approach”) for an eye-popping seven hundred simoleons.

Spritz, Inc. recently co-sponsored the LA Hacks event at UCLA Pauley Pavilion, where over a thousand young coders had gathered to compete for a five-thousand-dollar prize. When I arrived, near the end of the competition, the lobby was full of crashed-out kids in sleeping bags, while the basketball court was covered with tables crammed with open laptops, each one with a bleary young contestant or two before it. The genial Spritz executives, gamely dressed in white Spritz t-shirts, including Frank Waldman, the company’s co-founder and CEO, were looking a little worse for the wear. Waldman demonstrated for me how he could toggle between reading email, news and books on his various devices using Spritz. “The reason you don’t finish [ebooks] is that you don’t have that block of time available,” he told me. “But if I could read, say, two pages at a time… I rip through a couple of pages of the book. If I’m near the end, I can flip it into Spritz mode, and I just power through! Done. You know that feeling you get, when you finished the book?”

Though Spritz claims to have perfected RSVP and to have based its modifications on scientific analysis, experts have in general shown no love for the idea that RSVP systems such as Spritz and Spreeder offer any significant improvement in reading.

“Many of their claims appear to be false,” Mary Potter, a professor of psychology in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT who has been working with RSVP since 1969, wrote to me in an email. “I have done numerous experimental studies using RSVP to present sentences and paragraphs, and my work showed that although one can easily read at 12 words per second, and momentarily understand what one is reading, memory is very poor for material presented at that rate.”

When asked to compare ordinary reading with reading using RSVP, Dr. Potter replied, “I doubt if RSVP-based reading is ever superior to ordinary reading, other than for amusement. Whether it could be used in some way to improve reading skills, I don’t know: possibly […] Like so-called speed reading, I think the hype about RSVP-style reading will fade as people discover that it can be fun to try and can give the illusion of an easy way to take in information, but that it is in fact not a substitute for normal reading.”

I prefer to think of reading, as it has often been described, as a conversation, and what a conversation requires is the absolute opposite of speed. The literary conversation requires pauses, here and there. You might fix a cup of tea, meander around in the book some more. Interrogate the author, wonder what he might think of your ideas. Other authors might come along to weigh in. Half of the procedure is just reflecting, sometimes absently, sometimes in a boiling or stone-cold fury, or amusement or excitement, on what is being said. On responding.

I don’t think it would be too far off to compare the difference between Spritz and conventional reading to the difference between bolting a glass of Soylent, and savoring a beautiful dinner with friends.

Louis Émile Javal, the famed opthalmologist, contracted glaucoma and, after an unsuccessful operation, went blind. He bore the loss of his sight with great fortitude, publishing Entre Aveugles, a touching book for doctors treating those facing blindness, in 1903. Coincidentally, Helen Keller’s The Story of My Life was published that same year.

Helen Keller was the first deafblind person to earn a bachelor of arts degree (from Radcliffe College, in 1904) with the aid of her teacher, Anne Sullivan. She graduated with honors in German and English. How did a deafblind student manage to understand ordinary lectures at the turn of the twentieth century? Anne Sullivan came with her to every lecture, and spelled each word with her own hand into that of her pupil.

The lectures are spelled into my hand as rapidly as possible, and much of the individuality of the lecturer is lost to me in the effort to keep in the race. The words rush through my hand like hounds in pursuit of a hare which they often miss. But in this respect I do not think I am much worse off than the girls who take notes. If the mind is occupied with the mechanical process of hearing and putting words on paper at pell-mell speed, I should not think one could pay much attention to the subject under consideration or the manner in which it is presented. I cannot make notes during the lectures, because my hands are busy listening.

They did it, in other words, through what you might call an early form of RSVP (though it wasn’t technically V.) The words of the lectures streamed in not just one word, but one letter at a time. Genius like Helen Keller’s is very rare, but clearly it’s possible for an active mind to acclimate itself to new tools and new information, and gain undreamed-of levels of skill in reading. Perhaps it will be best to keep an open mind, as these new tools are introduced, while maintaining a healthy respect for the ones we have.

Maria Bustillos is a writer and critic in Los Angeles.

Photo by Charles Kremenak

Body Language, "4 Real"

Maybe a little too exuberant to play when it’s not sunny outside, or, at night, before your guests have gotten to their second drink. Context gives music life, and so context can TAKE IT AWAY. [Via]

10 More Truths About Dating a Bookworm

by Jake Swearingen

Previously: 10 Truths About Dating a Bookworm; Why Readers, Scientifically, Are The Best People To Fall In Love With.

1. Without lungs or other respiratory organs, we bookworms breathe through our skin. So we’ll never hog the blankets!

2. Our skin exudes a lubricating fluid that makes it easier to move underground, as well as keeping our skin moist. But please, don’t try to borrow our lubricating fluid: we need it in order to burrow beneath the earth and your Kiehl’s is gonna be better for your T-zone anyways.

3. We bookworms really hate birds. And fishermen.

4. We are simultaneous hermaphrodites — so keep your cisgendered assumptions to yourself! That said, we do need others in order to sexually reproduce, just be prepared to be GGG in the bedroom.

5. We bookworms will consume about one-half to one times our body weight every day! So keep that fridge stocked. (Don’t worry: we’ll totally go in halfsies on groceries.)

6. We bookworms lack arms, legs or eyes. So a night at the movies? Probably not. A night in a pile of freshly tilled dirt? Yes, please!

7. We bookworms mainly thrive where there is food, a good level of moisture in the soil, oxygen and livable temperature. But the most important ingredient? Love.

8. It’s true that bookworms are cold-blooded animals — we’re the first to admit that. But view it as a positive: We need someone (maybe it’s you?) to warm us up!

9. To help aid circulation through our elongated body, bookworms actually contain five hearts — which means we have five times the love to give!

10. There are nearly 2,700 different kinds of bookworms in the world, and we’re all unique. Before you make any assumptions, try to get to know us — we may just end up surprising you!

Jake Swearingen runs the online stuff at Modern Farmer. You can find him on Twitter and in real life covered in dirt and loving it.

Photo by Sheila Sund

Conflict Apps

by Noah Kulwin

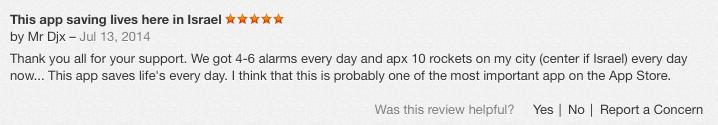

Red Alert: Israel is currently the second-most downloaded news app in the US, just below Yahoo. A selection of reviews from the App Store:

And one from Congressman Jeff Duncan (R-SC):

Why do I want the App? So that I can pray for Israel as well as understand, as a policy maker, the magnanimity of the threats and the conflict.

Can you imagine living under this constant threat?…

This speaks to the existential threat that the people in Israel live with constantly.

Red Alert’s creator is Kobi Snir, an Israeli developer who worked with the people behind Yo! to build an app that would send push notifications when rockets are launched into Israel. Initial press reports in American tech media focused on this angle in particular — how the useless-yet-VC-funded Yo! suddenly developed a very real and practical application.

The app is visually and functionally simple: When a rocket is fired, some sort of information pipeline between the Israeli military and Red Alert, which the app’s creator declined to discuss in an interview with The Times of Israel, lights up, and a notification is sent. A sample alert might read “Rockets Attack: Kiryat Malakhi.” You can narrow down the areas you want to monitor, or monitor them all. In theory (and in practice thus far), the notifications give an Israeli enough time to hurry into a bomb shelter.

For users of Red Alert here in the US, where it seems to be wildly popular, the app does something else: It simulates panic.

It lends non-Israelis a kind of performative empathy for Israel while reifying Israel’s “siege mentality” — the country’s inability to make the necessary concessions to achieve a peace deal with the Palestinians, as it feels besieged by critics at every turn. For the many reviewers who translate their “annoyance” with tens of alerts in a single day into empathy for Israelis living under rocket fire, the experience is tidy: ever-so-slightly visceral, affirming, and unchallenging.

The Israeli government has used Red Alert as part of their campaign to sell the morality of their airstrikes on, and potential ground invasion of, Gaza. Israeli ambassador to the US Ron Dermer’s interview with Bob Schieffer was on message and right on time. From the Israeli news service, Yedioth Ahronoth:

The rocket alert siren interrupted Israeli Ambassador to the US Ron Dermer’s interview on CBS’s “Face The Nation” on Sunday, in a vivid demonstration of what life is like in Israel under rockets threat from Gaza.

Dermer told interviewer Bob Schieffer about a smartphone app that plays out the rocket alert siren the moment it is sounded in Israel, and tells the user where in Israel the rocket is headed.

Not long after that, Dermer’s phone sounded the alarm. “The rocket is heading for Gedera, where my mother was born,” Dermer told Schieffer.

Since the violence escalated on July 7, there have been 209 Palestinian casualties to a single Israeli killed by mortar shrapnel. (The Palestinian equivalent to something like Red Alert would make your phone vibrate consistently but softly — enough that it can’t be ignored, but at a volume inaudible to everyone around you.)

None of this is meant to detract from the danger that the rockets pose to Israelis who live within firing range, as their fear is real. For the Israeli families in Sderot, Ashkelon, or Be’er Sheva (where I once lived), Red Alert is palliative.

But Red Alert commodifies the pain of war, and helps render invisible its toll on Palestinians. It turns the conflict into a monetized app, with Google-powered ads scrolling at the top of the screen and furious, scattershot comments crowding at the bottom. Red Alert, in addition to assisting Israelis on the ground and gathering advertising dollars, serves the purpose of a government that has the privilege of being able to sufficiently protect its citizens. The people of Gaza have no such luxury.

Noah Kulwin is The Awl’s summer intern.

The Pathos of Pageviews

“We are, absolutely, a page-view-driven site even though we don’t want to be,” said Mr. Magnin of Thought Catalog. “Every writer wants to do well, and ‘do well’ means get more Twitter followers.”

Imagine the day that the highly emotional new new internet completes its project to convert share metrics into the only acceptable form of currency. Go ahead, just revel in it. Renting this apartment requires forty thousand Twitter followers, with fewer than twenty-five percent of them being bots. The price for this dinner is a thousand Instagram followers and thirty-seven likes per photo. You can enter the Jeff Koons retrospective after sending Yos to six friends, three men and three women.

Money, which by 2023 becomes mostly used by tech companies to purchase other tech companies with different share metrics, wasn’t all that great anyway.

New York City, July 15, 2014

★★★★ Sweltering humidity at its purest, unboosted by any overt solar heat. For once, and briefly, it was worth stepping into the office air conditioning, after the airless stairwell. Then the monstrous chill regained its monstrousness. The outside darkened. Mobile phones whined en masse, if not in perfect synchrony, with arriving flash-flood warnings. Suddenly and quietly a solid downpour was falling — and then came a loud growl of thunder, then a sharp clap of it, then a long sustained boom. Another boom followed, sounding very specifically overhead. The street-side windows were white with rain. A roll and a crash; a roll that turned into a crash. Ten minutes went by, fifteen. The booming abated and the rain became an ordinary steady rain. The sky stayed dark, and it was noticeably cooler. The rain stopped long enough for the fire escape to dry out, then fell again on the evening commute. Once more it stopped, then, with three evenly spaced shell-bursts of thunder, returned for an indefinite soaking.