A Cat-Sized Chinchilla Objects to Media Narrative

by William Petrich

“’Extinct’ cat-sized Chinchilla found alive in shadows of Machu Pichu” — Jeremy Hance for Mongabay, part of the Guardian Environment Network

“This Guardian piece is pure clickbait!”

cries the cat-sized chinchilla.

“How dare they suggest our birth rate

is but a scintilla.”

“How droll, Guardian, putting ‘extinct’ in quotes,”

calls the cat-sized chinchilla,

“when my family alone would fill boats,

A whole ‘extinct’ flotilla.”

“We’re ‘found alive’ from Peru to Katmandu,”

chides the cat-sized chinchilla.

“So why does the Guardian willfully eschew

my many cousins in Anguilla?”

“And ‘cat-sized?’ Really? That’s the best you can do?”

concludes the cat-sized chinchilla,

“Well then, Mr. Hance, here’s my headline for you:

‘Succinct writer’ is man-sized Gorilla.’”

[Ed. note: The Machu Picchu arboreal chinchilla rat is probably more closely related to nutria than a true chinchilla, but that is neither here nor there.]

William Petrich sits in Washington, D.C.

Photo via

This Week in Lines

by Jake Gallagher

1:12 PM Thursday, September 25 — Shake Shack

Location: Madison Square Park

Length: Forty-one people, thirty-one umbrellas

Weather: 63 and rainy

Crowd: Unflappable fry fans

Mood: Soggy on the outside, crispy on the inside

Wait time: Eighteen minutes

Lingering question: How much rain does it take to stop the Shack?

Time and date: 11:39 AM Wednesday, September 24 — Subway ticket kiosk

Location: Grand Central

Length: Twenty-six people

Weather: 72 and partly cloudy outside, dank down below

Crowd: Paunchy tourists with backpacks as bloated as their bellies

Mood: Affable enough to clearly not be natives

Wait time: Twenty-five minutes

Lingering question: Do you not see the open machines over there?

1:33 PM Thursday, September 25 — Vamoose Bus Line

Location: 30th Street and 7th Avenue

Length: Twenty-two people

Weather: 63 and drizzling

Crowd: Urban escapees

Mood: Blasé

Wait time: Twenty-seven minutes

Lingering question: Does a Chinatown bus ever actually have to leave from Chinatown?

Jake Gallagher is a writer for A Continuous Lean and other places.

The Chosen Vegetables

The cuisine of the Ashkenazic Jews is kind of awful. This is not the fault of my people; they tried their best, they really did. But the climate, socioeconomic struggles, and raw materials they had to work with left them with some pretty rough dishes. Worst, in my mind, is that there are a few big Jewish feasts in the late summer and early fall — the best time of year for produce — and Ashkenazic Jewish food doesn’t take advantage of that. So I would like to propose a way to make the feasts of early fall — Rosh Hashanah and the breaking of the fast after Yom Kippur — a little more vegetable-friendly: We must unite the cuisines of the Jews.

First, some history: Amidst lots of wars, large waves of Jews left Israel around the fourth century A.D., settling mostly in the Mediterranean climates of Italy, France, Spain, and Morocco. Over the next thousand years or so, they experienced varying degrees of hostility in these places at various times, and most were eventually booted to the cold lands of the Russian Empire. Some did okay in the cities, but others were stuck in ghettoes, which were occasionally burned down; sometimes they were imprisoned or chased around or killed. Their food options, to say the least, were limited.

The Jews were used to some of the most fertile land in the world; eastern Europe must have been a brutal shock for them. Now called Ashkenazim, they created the best cuisine they could for cold weather, given the garbage they had to work with: starches, soups, fatty cuts of meat, and boiled root vegetables, largely adopted from Polish and Russian cuisine. When they finally made it out, mostly to North America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they brought this stuff with them, where some of the dishes got so popular they assimilated into the general umbrella of American food: Bagels, challah, latkes, and matzoh ball soup are as American as pizza, tacos, and pork fried rice.

People who aren’t into meat and fat will find that the centerpiece dishes of Ashkenazic Jewish cuisine tend to be very fatty and very meaty, like braised beef brisket, cholent (a slow-cooked stew of beef, potatoes, and barley) or kishke (an often-bland sausage made of beef intestine stuffed with flour or matzoh meal and chicken fat). They also often have a sweet element that can be cloying, since Jews worldwide love to put honey and apples and dried fruit in savory dishes. The sides are typically bland filler, made of noodles or breads or various permutations of matzoh. Spices are exceedingly limited; herbs pretty much non-existent. The vegetables used are of the root-y variety, like beets, carrots, potatoes, and turnips, all of which are cooked in pretty much the same way (boiled). The only Jewish vegetable dish I can really remember growing up with is called tzimmes, a dish of carrots boiled in water and honey and sometimes sprinkled with raisins. It is an awful, awful dish; it reduces the carrot to baby food and it is disgustingly sweet, as are many Ashkenazic Jewish desserts.

The fact that we eat this sort of food is especially galling during the High Holidays because late summer and early fall has some amazing produce — at least in the Northeast where I and, according to census data, several other Jews, live. It seems a shame to cook as if we’re in the dead of winter in a shtetl in Białystok when in fact we’re surrounded by amazing fruits and vegetables: The early fall produce, from apples to kale to chard to squash, join — for a mere few weeks — the end-of-summer peaches, okra, green beans, tomatoes, and cucumbers on farmers’ market tables. We could make the argument (and I will!) that Jewish food, like most poor-people cuisines, is about using what you can find. And what I can find in Brooklyn today is a hell of a lot better than what my great-grandparents could find in Grodno.

LUCKILY: not all the Jews followed the path of my Ashkenazic ancestors. Lots of them stayed or ended up near the Mediterranean, either in western Europe (these we call the Sephardim) or in the Middle East (these we call the Mizrahi). And because they stayed in nice warm places where vegetables actually grow, their cuisines are completely different from that of the Ashkenazim, only vaguely connected pretty much only by the laws of Kashrut (Kosher). Instead of blending Jewish dietary laws and tastes with the frankly not very good foods of Poland and Russia, the Mediterranean Jews mixed with Spanish, French, Turkish, Syrian, Lebanese, Moroccan, and Algerian cuisines, among others, to create a variety of dishes that are nothing at all like what most non-Jews would think of as Jewish food. But it totally is!

For the fall feasts, I think we pale Ashkenazic Jews should explore the foods of our tanned, warm-weather cousins, because a lot of their food dovetails perfectly with what’s in season right now. That doesn’t mean abandoning our regional food; a bagel with lox and cream cheese is a delightful food to break a twenty-four-hour fast. But vegetables are good, too.

Since it’s the end of tomato season, how about shakshuka? The origins of the dish, like most Jewish dishes, is mixed up with the cuisine of whichever country the Jews happened to be living in at the time (in this case, probably Tunisia or Algeria), but it’s now often associated with Mizrahi food. To make: pre-heat oven to about 450 degrees. Fry onion, garlic, and a mix of sweet and hot peppers (your choice, but I like shishito for flavor, cubanelle for sweetness, and Thai chile for heat) in a cast iron pan in quite a bit of olive oil. When the peppers are soft, add cumin and smoked paprika, then stir to toast the spices. Take big stewing tomatoes like beefsteaks or Roma (because heirlooms would be a waste), chop them up, and throw them in. Cook down until thick, like a stew, then stir in the pesto of your choice (cilantro, parsley, or a combination would be good). Add salt and pepper here, because after this you won’t be able to fuck with it too much, and some chunks of feta or goat cheese. Crack a few eggs into the stew, being careful not to break the yolk, then shove it in the oven for a couple minutes. It’s done when the whites are mostly opaque but still a touch loose and pudding-y. The yolks should, of course, be runny. Serve with pita or bread. Or bagel, why not, this is all about friendship across borders.

Okra is a favorite vegetable of Middle Eastern Jews, especially in Libya and Syria. Another stew: fry onion and garlic, then add Aleppo pepper if you can find it (use one part ground cayenne to four parts sweet paprika if you can’t) and a small pinch of cinnamon. Slice okra (look for the smallest ones) into rounds and toss into the pan. Add in chopped tomatoes, chopped dried apricots and a little lemon juice. Cook it for maybe twenty minutes, until the flavors have all come together. Serve over rice or couscous with fresh mint and parsley on top. (I don’t have any special recipe for couscous. Bring water to a boil, measure out one part couscous to two parts hot water in a bowl, add in salt and a pat of butter, quickly stir and cover for about five minutes until the water has been absorbed. Fluff with fork.)

The Sephardim, like the Ashkenazim (and, I guess, everybody else in the entire world) are very into fritters. Latkes are great, but don’t really feel like late summer to me; moving to the Sephardic-style fritter, which are made with vegetables, feels fresher. Zucchini is an easy replacement for potato: Grate zucchini on a box grater into a big pile, then (and this is the most important part) wrap them in a towel and squeeze the shit out of them. You want as little water as possible. Then mix with either grated (this will destroy your eyes but is the best option) or minced onion, a beaten egg, and some breadcrumbs. Form into a patty and fry in vegetable oil, a couple minutes on both sides until golden brown. (These are called ejjeh kousa, and probably the Lebanese invented them.)

A more interesting twist comes from Poopa Dweck’s spectacular book, Aromas of Aleppo, and are called keftes de prasa. Hers uses leeks, one of my favorite favorite vegetables. Cut off the tough green part at the top and the roots at the bottom, then slice in half length-wise and wash very thoroughly (there’s going to be a lot of sand and stuff in there). Slice the leeks width-wise thinly, into little strips, and saute briefly in olive oil to remove some of that raw onion flavor. Then dump them into a bowl and mix with the standard items (beaten egg, breadcrumbs, salt, pepper) as well as some Syrian spices — a little bit of cinnamon, a little allspice, a little cumin, a little cayenne. According to Serious Eats, the batter should be “rather wet,” not quite like the patty you’d make with potato or zucchini. Serve with labneh.

Stuffed vegetables are also very common in Iberia and North Africa, and are nicely ceremonial (read: are a pain in the ass). Lots of stuffed vegetable recipes, here in America or in Greece or Italy, call for bell peppers. I hate bell peppers; they are the worst of all peppers. Instead opt for pattypan or otherwise spherical squash, or big tomatoes, or even some other kind of pepper, like a New Mexico pepper. First things first: Put some rice in water to soak for at least half an hour, and get some pine nuts or walnuts in a dry pan to toast until fragrant. If using squash or tomatoes, saw off their top and then scoop out the guts with a spoon, getting as close to the walls of the fruit as you can without busting through. Chop up the guts. In a pot, saute onion and garlic in olive oil, then dump in your spices: turmeric, cumin, cinnamon, dried chile. Stir. Then add in the guts of whatever you’re stuffing, along with a whole mess of chopped spinach. Add in a tiny dash of red wine vinegar and cover until the spinach has cooked down. Then throw in your walnuts, plus some kind of dried fruit. (Raisins are good, as are currants, or even apricots or cherries.) Drain the water from your rice, and mix the rice in with this whole mess. Make sure it’s not too dry; add a little water if it seems so. Stuff this insane mixture into your hollowed-out vegetable shells (not too much, though, since the rice will expand). Bake at 350 degrees until the rice is cooked, about twenty minutes. Serve with labneh.

Oh right, labneh! Labneh is a dairy product somewhere in between yogurt and soft cheese. You can buy it, but don’t, because the pre-made stuff is weirdly expensive and can be hard to find even though it is incredibly easy to make. To make it, get out a strainer and line it with cheesecloth or, hell, a clean dish towel that’s on the thin side. Take full-fat Greek yogurt (Fage is good) and dump it in there, add a little salt, and gather the top of the cheesecloth or towel to make a little bundle. Put it on top of a pot or bowl or something, because the goal here is to strain out most of the water in the yogurt, and put it in the fridge overnight. The next day you’ll have labneh, an amazingly tangy and thick yogurt/cheese thing which goes great with pretty much all vegetables and herbs.

I don’t mean to decry all Ashkenazic Jewish food, or suggest that we Eastern European Jews should abandon our roots. All I’m saying is, objectively, if you had to choose a cuisine to mix with, would you pick Lebanese or Polish? Spanish or Ukrainian? Moroccan or Russian? Yeah.

Crop Chef is a column about the correct ways to prepare and consume plant matter, by Dan Nosowitz, a freelance human who enjoys hot salads and lives in Brooklyn, naturally.

Photo by Joy

Dev Hynes, "Everything Is Embarrassing"

Lost in the slightly tense but mostly tepid feud between songwriter Dev Hynes (aka Blood Orange) and Sky Ferreira over artistic ownership of “Everything Is Embarrassing” is the document itself. Ferreira’s version, the enormous hit, is slick and perfect and instantly imprints itself on your brain, where it is stored as just one or two repeating stanzas. Hynes’s version, a functional and unpolished demo, feels small and tentative — it sounds embarrassed.

A Poem by Lo Kwa Mei-en

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Passion with an Operating Theater Underneath It

Every day is take your knife to work day Every

Body begs its answer — even hard ones —

Hard of need, hard of hand in hand, harder up

Than a good night in a short glass That’s my

Preferred exorcism meant excision method doll

Who will say please with her eyes rolled back in

The tomb Medical blood miracles and Marys down

Mary is down with the boys this time, mister

Magdalene, mourning you I mourned you too wet

To stay clean until the very earth wiped

Down and out One outtake of ethic length where

I love you but still count down from five

Like a hero who can count to six to save her life

It’s okay Every sundown I fall down too

Stainless to be silver or risen thing like the sea

Or melodic in place of what fell back

In place of a heart a thing that can breathe on its own

Sell that out and we can roll back stones

Don’t you ever wonder where all that red went

Don’t you love me too much to look

But I sing There’s room in me for one last knife

And the view from the balcony always moved you

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

Lo Kwa Mei-en is the author of Yearling, forthcoming from Alice James Books.

The Rodent and the Mayor

Brian Morris, a spokesman for the zoo, said officials were in the process of revisiting animal protocols, and it was “more than likely” that new rules would keep mayors and groundhogs from coming into contact every February.

“It’ll protect our animals,” he said, “and it’ll also protect whoever the mayor is.”

Keeping large rodents out of the hands of towering New York City mayors will no doubt save their lives, given the recent events that led to the death of Charlotte, aka Chuck, the mystical groundhog — but what grave harm, exactly, must the mayor be shielded from? The conspiracy is real, folks.

New York City, September 24, 2014

★ Thin clouds moved over the morning sky. The air was cool and humid; the sun hung around for awhile, making shadows fade in and out. The clouds thickened and rumpled. By afternoon it was chilly up on the roof. A young man held onto a walk/don’t walk sign and dangled from it for a photographer. His ankles were bare but he wore a knit hat. A couple of actors walked down Prince Street, hand in hand, with a camera and a crew retreating before them, undeterred by the lack of autumnal brilliance. The grays in the clouds, darker under lighter, gave way at sunset to an unexpected flood of pink.

The Drivers Must Roll

The Drivers Must Roll

Here is some totally unhelpful but still fascinating background decoration for Uber’s incredibly rapid recruitment, containment and domination of its drivers, who, if they work in New York, just found out that their recently and suddenly reduced rates are now permanent, despite protests. It’s a passage from Robert Heinlein’s 1940 short story, “The Roads Must Roll,” in which cars have been replaced by enormous conveyors operated by a largely invisible network of technicians:

The speaker pressed his advantage, his words tumbling out in a rasping torrent. He leaned toward the crowd, his eyes picking out individuals at whom to fling his words. “What makes business? The roads! How do they move the food they eat? The roads! How do they get to work? The roads! How do they get home to their wives? The roads!” He paused for effect, then lowered his voice. “Where would the public be if you boys didn’t keep them roads rolling? Behind the eight ball, and everybody knows it. But do they appreciate it? Pfui! Did we ask for too much? Were our demands unreasonable? ‘The right to resign whenever we want to.’ Every working stiff in any other job has that. ‘The same Pay as the engineers.’ Why not? Who are the real engineers around here? D’yuh have to be a cadet in a funny little hat before you can learn to wipe a bearing, or jack down a rotor? Who earns his keep: The gentlemen in the control offices, or the boys down inside? What else do we ask? “The right to elect our own engineers.’ Why the hell not? Who’s competent to pick engineers? The technicians — or some damn dumb examining board that’s never been down inside, and couldn’t tell a rotor bearing from a field coil?”

He changed his pace with natural art, and lowered his voice still further. “I tell you, brother, it’s time we quit fiddlin’ around with petitions to the Transport Commission, and use a little direct action. Let ’em yammer about democracy; that’s a lot of eyewash — we’ve got the power, and we’re the men that count!”

It’s a strange story with some great lines:

[Automobiles] contained the seeds of their own destruction. Seventy million steel juggernauts, operated by imperfect human beings at high speed, are more destructive than war.

It’s also a work of adventurous and pulpy speculative fiction, in which the world is powered by a “Sun-power screen” and road workers the country over have been seduced by a radical “Functionalist” philosophy that says — and this is all we ever really get to find out about it — that it is “right and proper for a man to exercise over his fellows whatever power was inherent in his function.”

In the story, the power “inherent” in the road-workers’ function is dangerously great, in part because of the design of the road and in part because they are formally organized; in real life, in our actual budding dystopia, the prospect of an effective labor movement for Uber drivers does not seem plausible at all.

While there was talk of drivers unionizing at Friday’s meeting, the protest appears to be struggling to reach and mobilize a critical mass of Uber drivers. Much of the organization appears to be haphazard, with drivers relying on personal networks and cold-calling.

“Text every driver you know,” Abdoulrahime Diallo, one of the organizers, instructed the protesters. “It’s worth the investment, tell them to stand with us.”

Uber, which has openly professed its intention to scale as quickly and in as many infrastructural directions as possible, did not seem bothered by a series of protests in the city, suggesting that it would consult its internal data to decide whether or not to make the surprise fare decrease permanent. The data said whatever Uber expected or wanted it to say, and so it’s sticking to its plans. Everything else is noise. Noise is inefficiency. Its drivers are to have no power, inherent or otherwise.

It’s literally and politically of a very different time; unions are increasingly treated like a spent sci-fi trope, and the equivalent workers today wouldn’t be asking for better terms so much as any reliable terms at all, or the right to secure them. Also, I don’t know — would the impatient and proudly Randian Travis Kalanick be, in this fictional universe, seduced by Heilein’s Functionalism? I think maybe! Or would he, according to his company’s insistence on strictly monitoring the ratings of its contractors, be more sympathetic to the bureaucrat who concludes, when stability is restored, that “supervision and inspection, check and recheck, was the answer” all along? Or is he just putting off worrying about any of this until drivers are replaced by actual robots.

The Internet Has a Problem(atic)

by Johannah King-Slutzky

The word “problematic” is a firehose for — what, exactly? I know it’s loud and sprays everywhere, but I can’t locate its target. It is common knowledge in certain corners of the internet that “problematic” is codependent with the think piece, that short, poorly researched form of essay that exists to criticize recent cultural phenomena on usually disingenuous political or moral grounds.

Fifty years ago, “problematic” was modest, mousy and rare, maybe akin to “thole” or “vellicate” — nice for a dinner party, but far from a buzzword. Today, you can’t go online without bumping into a “problematic” or two: “Hip-hop videos featuring bling and babes” are “problematic”; “The Promising…Future of Ultra-Fast Internet” is problematic; “psychological process — which underpins racism, extreme nationalism, and prejudice of all sorts” is problematic; “resolutions, as Oscar Wilde knew,” are problematic; “videogames” are problematic; Miley, Katy, and Iggy (not Pop) are problematic. In the academe, “the modern Chinese self…caught between tradition and modernity” is problematic, as are the “Fictions of Poe, James and Hawthorne” and “Ordering in French Renaissance Literature.”

I’M problematic? YOU’RE problematic! this whole TUMBLR is problematic!

— adult contemporary (@chuchugoogoo) September 6, 2014

@911VICTIM are you problematic

— Virgil Texas (@virgiltexas) August 31, 2014

[emerging from the forest cave where I’ve been pondering life and licking moss-covered rocks] Beyoncé is good…except when she’s problematic

— Sarah Jessica Wario (@McLeemz) August 25, 2014

Although vacuous, “problematic” has become shorthand for self-serious identity politics for several reasons, starting with its historically mechanical and apolitical connotations. To borrow a tagline from another failed experiment in seriousness, let’s Look Closer.

Imported from France some time around 1600, earlier iterations of “problematic” favor the word’s mechanical usage. From a review in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions in 1686, for example, you will find the statement, “I have inquired into Dr Papins [sic] problematic engine for raising water.” Or The British Cyclopaedia of the Arts and Sciences(1838), “Whether steam artillery will ever be employed for land warfare is somewhat problematic, as the weight of a steam gun is such as to preclude any degree of rapid locomotion…” It was also political back then, but not to the point of satire, as it is today. Here is the word’s older political usage, from the New York Times in 1854: “The axiom, that good may come from evil, may be true in some respects, but this good result is by far too problematic and uncertain to give any one the right to count on the life-blood, tears and sufferings of thousands as an invested fund of martyrdom…”

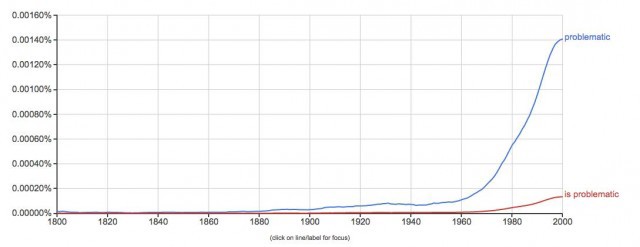

The word remained unpopular in English until 1960, when its ngram begins to resemble a hockey stick. There are at least four interrelated traditions responsible for the morphing of “problematic” from throwaway to political buzzword in the late-middle twentieth century: 1) the emergence of identity politics beginning in 1968, 2) the rise of the think piece in the nineteen seventies, with a second, ongoing spike that began around 2006, 3) the development of post-structuralism in the seventies, and 4) changes in syntactical patterns of academic English around the turn of the century.

One reason “problematic” lends itself so well to identity politics (and therefore, the think piece and certain flavors of post-structuralism) is because even before “problematic” became overwhelmingly political, many uses of “problematic” alluded to difficulty in representation. The Oxford English Dictionary motions to, but does not outright state this, with its parsing of “problematic” as “difficult to decide.”

Take, for example, this early use of “problematic” in The London Intelligencer, on Signior Dominica, former Valet de Chambre to King James II:

His Religion was very Problematical, for sometimes he discursed like a Roman Catholick, sometimes like a Protestant, at others he shewd such Respect for Rabbinical Learning, as might have created a Suspicion of his being a Jew; but then he was deeply read in the Koran, and might as well have been taken for a Mahometan. (1–3 October 1751)

Same goes for this entry on Napoleon’s army, from The London Sun, 7 July 1800:

All that the Paris Papers state to have been brought by the Chief Consul, is the Ratification of the Armistice. Even this appears to us more than problematical, for, if it had been true, it cannot be doubted that BONAPARTE would have mentioned the fact among the numerous speeches which the Paris Journalists ascribe to him, who appear greedily to collect all his conversation, we know not, in fact, whether with a view to excite our admiration or our ridicule.

Not only are both entries about difficulty in detection, but both are about representation in classically conceived mediums — in the first example, religion as mediated through speech; the second, the details of an armistice as represented in Napoleon’s oration and press.

The representational leanings of “problematic” are not totally divorced from the mechanical. Like identity politics, “problematic” often refers to representational difficulty with physical effects. For example, from the eerily-named 1905 article “Death to Jackrabbits”:

The electric headlight, they say, is doing the business, for it seems to stupefy and frighten cold the long-eared creatures which sit on the track until they are run down and killed. Just how many thousand jackrabbits there are along the Southern Pacific is problematic, but the railroad men say that the ranks of the representatives of Kansas are rapidly being thinned out.

This usage of “problematic,” which is typical for its time, is illuminating because it pre-dates what we now traduce as “identity politics.” Not only race and sex, but the lineaments of human bodies altogether are absent from this 1905 musing on jackrabbit populations. Even so, the newspaper clipping includes two of identity politics’ constituent features: representational difficulty (in an ecological survey) with physical consequences (death of jackrabbits). But this is only a loose relationship. “Problematic” in identity politics means “bad representation” in two senses of bad: (a) inaccurate, and (b) hurtful. When the Tuscon Sun ruminates on jackrabbits, (a) inaccurate accounting does not cause (b) dead rabbits.

More recently, the mechanical flavor of “problematic” comes through in political metaphor, where it can be a way to mask ideology with practical critique. That’s how you end up, in 1955, with this LIFE editorial about legitimacy in government:

It is problematic in the new governments of Asia, since legitimacy requires time to establish itself. But time is not the only consideration: even the Communist regime of Yugoslavia, whose revolution had a national base, could earn legitimacy quickly if it will trust and be trusted by its people.

What makes the new governments of Asia problematic? Certainly it’s not that they’re communist: It’s because “legitimacy requires time to establish itself” — like allowing your oven to pre-heat or bacteria to culture; not so different from the Royal Society’s 1686 “problematic engine.”

In the modern think piece, “problematic,” like “identity politics,” is about the representation of bodies with real-world effects, generally along favored axes like race, sex, class, physical ability, and sexual orientation. These particular axes became the categories of identity politics some time between 1970 and 1990. Bob Guccione in the November 1992 issue of SPIN lays it out for us:

This is an election between us — you and I — and George Bush and his extreme conservative factions, who have already had a strangling effect on America and, in 12 years, have turned this country from a problematic but intellectually and socially progressive nation, into an infinitely more problematic and desperately regressive society, rife with racism, poverty, illiteracy, and general social abandonment.

Which problems are “problematic”? By the late twentieth century they were racism, poverty, illiteracy, and general social abandonment — all issues closely associated with what we call identity politics. “Problematic,” which has always lent itself to representational and mechanical error, blends the right connotations — difficult representation and real world effects — to suit identity politics. In many ways, identity politics, which are overtly representational, treat bodies like positivist machines that know more than the self-deluding mind. So one reason “problematic” has flourished in the last fifty years is because it works well with this post-1968 moment (which we’re still in).

Not unrelatedly, “problematic” owes its most recent spike to the emergence of the think piece, which is “a piece of writing that responds to a recent cultural product, event, or phenomenon, and attends specifically to its social and political implications.” That’s from Joseph Staten, a student at The New School who delivered a paper on the think piece last spring at Theorizing The Web. Staten argues that “The keyword of the think piece…is ‘problematic’” and that “problematic,” which is political, is used to obscure the aesthetic qualifications of pop culture.

There is almost no research on the history or definition of think pieces. Slate’s David Haglund traces think pieces back as far as 1930, but the early think pieces he identifies qualify in name only: The phrase “think piece” that appears in the 1936 Nation article Haglund cites does not refer to “a piece of writing that responds to a recent cultural product, event, or phenomenon, and attends specifically to its social and political implications,” but to the practice of quoting from supposedly anonymous sources as a way to advance the journalist’s own views in a thinly reported piece.

When I did my own research, I found “problematic”-saturated think pieces budding in specialty publications around 1970. Here is an entry from the Berkeley newspaper El Grito, from September 1st, 1970:

As he steps into this arena to partake of its explanatory fruits he must necessarily step into its many academic bogs as well. Of this there can be no avoidance. This is because being Mexican-American alone does not dispel the problematic characteristics of social science research in general. In this light this issue of El Grito speaks directly to some of the problems that are to be encountered by Mexican-American social scientists in the production of objective and scholarly research on the Mexican-American.

This is an early think piece: it addresses a recent change in culture and criticizes a cultural group’s representation with political implications. Like contemporary think pieces, El Grito also borrows from poststructuralism when it spatializes academia as — in the article’s own words — an “arena” to be “stepp[ed] into.” And although “the historically all white arena” does not “interrogate,” to use a favorite metaphor of the poststructuralists, it at least “speaks.”

Think pieces — and “problematic” — have grown in popularity as the newspaper industry has suffered. The explosion of news media, including endless TV news and hyperlocal news blogs, meant that elite authors needed authoritative language to mortgage credibility and distinguish themselves from the fluff. Newspaper and blog writers have almost certainly appropriated that credibility from academic English by using self-serious words like “problematic.”

The data reflects this. If you look at a timeline of “problematic” in Google Books you’ll see that it got a huge spike in use around 1960:

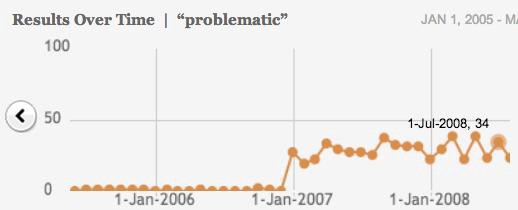

But if you look at “problematic” in newspapers like the Washington Post, you’ll see that “problematic” doesn’t get a spike until 2007:

From the Washington Post’s website.

(This chart is not a paper-specific fluke. For contrast, the New York Times used “problematic” only seven times in 1910 and six in 1920, but in 2000, it “problematic” showed up two hundred and fifty times. Last year, it appeared six hundred and twenty-five times in print, and two hundred and sixty-six times online.)

The gap between English-in-books and English newspaper usage suggests that by the time newspapers and blogs took up the mantel of “problematic” it already had the tone of non-newspaper dialects. Perhaps it borrows from academic English, a term of art used by linguists; it sounds academic, largely because it suits itself to grammatical structures prevalent in academic language. According to linguists Douglas Biber and Bethany Gray, the primary features of academic English are its higher-than-average noun-to-verb ratio, and phrasal, rather than clausal, embedding, which is another way of saying there aren’t many finite dependent clauses in academic English. So, the phrase “the assertion is incorrect” — which is in academic English, with no dependent clauses and few verbs — might become “whoever said that is wrong” in conversational English, where it has a dependent clause, finite verbs, and a low noun-to-verb ratio.

But think pieces rarely speak only in academic English. Tracking down syntax in think-piece English is especially complicated because even publicists have begun to use “problematic” in speech without following the rules of either newspaper or academic English. For example, in a pre-draft interview with NBC News, Cyd Ziegler, the founder of outsports.com, said of Michael Sam, “For them not to select him would be very problematic.” Ziegler parroted think piece jargon and his sound byte made it into many post-draft think pieces, but it doesn’t follow newspaper or academic English standards. This pidgin — think-piece English? — is replicated in different forms, not just in news interviews, but also in tweets, Facebook shares, gchats, and other social media which hybridize conversational and professional syntax. Think-piece English is not a stable target because the think piece is an invention of the social media’s web and gets blended with conversational syntax all the time.

That being said, it’s easy enough to identify the different strains of “problematic” currently in use. Using Michael Sam as a case study, we can see that one common formulation is “x is problematic,” as in Cyd Ziegler’s “For them not to select him would be very problematic.” “X is problematic” tends to be restricted to spoken quotes, like Ziegler’s, and headlines, which follow their own set of rules. This formulation is so thoroughly encoded in the logic of think pieces that you get headlines that sound like “problematic” chop and screw, such as Bustle’s “Hey Shailene Woodley: Your definition of feminism is really, really problematic” and Slate’s “Is the Portrayal of Women in The Newsroom Problematic?” “X is problematic” is not academic at all, although to the uneducated ear it might sound like it. A more academically inflected think piece wrote, “Michael Sam has faced intense scrutiny and media attention since coming out, but the focus speaks less to his ability than a problematic NFL culture.” Here, “problematic” is a modifier in a noun phrase that comes after the head verb — very academic — but the dependent clause is more newspaper than academe. “Problematic” has academic authority, from which users like Ziegler and many thinkpiece authors borrow inexpertly.

So let’s add a third allegation: not only did “problematic” become popular because it suits identity politics and sounds smart, it’s also highly shareable. “Problematic” bundles urgency, seriousness, and debatability into a single vague word, which is great for both sound bytes and tweets. Perhaps coincidentally (but probably not), these double prongs of technology — TV news and social media — correspond chronologically to the double spike you get in “problematic” in the sixties and early aughts. You don’t need to know the specifics of a “problematic” allegation to share it on Facebook.

If the appearance of “problematic” does not always follow the letter of academic English, it certainly follows the spirit, which is obscurantist. Academic English etiolates cause and effect. Nominalization and passive sentence construction both muddle academic writing’s waters, which is how “John Smith manages hazardous waste” becomes, through the lens of a professor, “hazardous waste is managed.” This is where “problematic” becomes really useful. “Problematic” will tell you what is problematic — usually race or gender — but it won’t tell you who did what, when; there are no finite verbs. Take this thinkpiece on #CancelColbert, from Salon: “To grow up in America is to receive racially problematic and stereotypical ideas about people of color almost by osmosis.” What is problematic? Ideas! About people of color! But cause and effect are abstruse, the author even casts her personal story in the infinitive, “to grow up in America.”

Two years ago, Alix Rule and David Levine remarked on a similarly obscurantist art world phenomenon in their Triple Canopy article and plenary, “International Art English.” (Actually, because it was Triple Canopy, the title was all lowercase, “international art english.”) The lexicon of IAE, say Rule and Levine, is “pornographic” — you know it when you see it. It includes words like aporia, radically, space, proposition, biopoliticial, tension, transversal, autonomy, interrogate, question, encode, transform, subvert, imbricate, and displace. Everything in IAE becomes a noun. “Visual” morphs into visuality, “global” to globality, “potential” to potentiality, and so on. “Problematic” does not belong to IAE’s more elite oeuvre, but as any humanities undergrad worth her salt knows, it’s a close second. Like many of poststructuralist journal October’s essays, “problematic” and its more aspirational cousin, “problematize,” sound poorly translated, one suffix tacked on another like German nouns. Rule and Levine might as well be talking about “problematic” in the think piece when they write, “[L]anguage had a job to do: consecrate certain artworks as significant, critical, and indeed, contemporary.”

Many linguists have remarked that academic writing “has not always been unelaborated and implicit in the expression of meaning relations.” Why has academic writing changed? In their examination of academic English, Biber and Gray suggest it has to do with the invention of typewriters and word processors, without whose editing faculties all that phrasal elaboration — its sheer differentness from conversational English — would rebuff print. Basically, say Biber and Gray, you cannot think in academic English, you can only wrangle post hoc. In this roundabout way, they imply, Microsoft Word husbanded identity politics in the late twentieth century. I’m skeptical — I think in academic English all the time, to my detriment — but they’re right that language and technology aren’t antipodes. The computer didn’t give us “problematic,” but it may have contributed to obscurantism in academic and art English, of which “problematic” is a part, just as social media and CNN made “problematic” phatic for “short, smart and shareable.”

To some, this is not news. The Crisis, the NAACP magazine founded by W.E.B. DuBois in 1910, speared “problematic” through its core in 1980 when it wrote:

When an issue is problematic, it is simply open to question or debate and difficult to solve or decide; when that issue reaches crisis proportion, it becomes the turning point for better or worse — the decisive moment in unstable or crucial times or state of affairs whose outcome will make a decisive difference for better or worse in and on the lives of those persons affected.

Problematic situations are never crises, which is damning when you consider that “problematic” tends to be used in critical discourse on racism, sexism, and homophobia. “Problematic” whines; it does not act. It takes baths. But most of all, it, like racism, sexism, classism, ableism, and heterosexism, is definitely bad for indefinite reasons.

Johannah King-Slutzky is a blogger and essayist from New York City. Photos by _tar0_.