Eight Voicemails from My Grandmother, Who Is Very Upset About the Apparent Death of My Career

by Samantha Henig

This weekend marked the end of the the New York Times Magazine’s Meh List, a feature for which I have been the chief columnist for the last two years. Writing The Meh List takes up approximately five minutes of my week. (My real job is as the magazine’s digital editor.) But The Meh List is in print. The Meh List has my byline. Therefore, for the purposes of my ninety-year-old grandmother, The Meh List was my job. When I told her last week during our family’s Rosh Hashanah gathering that the Meh List was about to end, she waited until we had parted ways to unload her concern onto my mother. “No more Meh List?” Grammy asked her. “Then how will her bosses be able to be judge how well Sam is doing her job?”

As a farewell to The Meh List, here are eight voicemails from my grandmother about my Big Important Job that is no more, to be published on a medium that she does not understand and does not care to.

March 30, 2013, when I handed over the reins to someone who cares about the Mets for our annual Mehts List

Hi Sam, it’s your Grammy. The magazine has meh, but it doesn’t have Sam. I’m sure you know that. But you didn’t tell me. So tell me what it means. That’s it. Bye. Anything connected with my Sam I need to know. Bye. Love.

Hi it’s Grammy, and I’m reading the Meh List. Want to share with you that I think “ships in glass bottles” has always been a meh to me, so thank you for that, thank you indeed. But I don’t know what JWoww is. Or happy Friday. You’ll have to explain the others to me. But ships in glass bottles is great.

May 29, 2013, when I thought it would be good to get some other New York Times personalities in on the Meh game, starting with Brian Stelter. (I took on the “additional reporting and user experience” credit at the bottom of the list.)

Hi. It seems to be a quarter to nine. And I don’t know what day it is. Sunday? No? What day is it? You will know. This is your Grammy. I’m a little bit late in reading the magazine section. I’m a little bit late in everything. And the shock of — not the shock of my life, but a big shock was that the Meh List does not say “by Samantha Henig,” and I get a big kick out of it saying “additional support and…trial experience?” I can’t even read it right. By Samantha Henig. You didn’t tell me. Have you been promoted? Did they realize that your skills are in many other directions? Tell me what happened. This is your Grammy. Bye.

Hi, it’s your Grammy. Very proud of you, reading the Meh List. And I have to tell you that every once in a while I push it away, but here it is. I’m such a throwback, my love. The only items that are familiar to me are “mom and baby” and “the last two weeks of August,” and the rest I don’t know. I have so much to learn! And as they say, so little time. But lots of time to be proud of you my love. Bye.

Your magah [ed note: a family nickname for “grandma”] is looking at the Times Magazine and it says The Meh List by SAMANTHA HENIG, not additional reporting or anything. Your own name right there. I’m very proud. Whatever you wrote was adorable except I don’t know what Smith…wick’s is, but everything else I got, which doesn’t happen too often. So, I’m proud, I love you, and I’ll talk to you soon. Bye.

Hi it’s me again, and I promise, I hope, I think this is the last time today. I’m reading the Meh List, and you know, Samantha, I know that my birthday is coming up but this, what’s the word, reinforces the fact that I’m getting to be really old. On the Meh List, I don’t know anything except the last one; I remember Citronella sort of vaguely. I don’t know what pocket squares are, air plants, celebrity apologies…most of all what is a Latergram and what is 2048? So fill me in so I come to this century a little bit closer. Thanks sweetie. Bye.

I’m calling to say I love the Meh List today more than other days because it’s got that beautiful name right up front. It doesn’t say “additional reporting by,” it says BY you. So I’m very proud. And of course I don’t know what half of them are. Like…Chris Pratt action hero? That’s the one that I basically truly don’t know. And I don’t know what a mechanical pencil is. So, fill me in. But I’m filling you in. I’m so proud, and I love you. And this is Saturday, because I get Sunday’s paper on Saturday! Part of it. Love, with pride, bye.

September 29, 2014, the day after the final Meh List ran in print

This is a fan … letter? Fan mail? How do you say that? Anyway, I’m a big fan of this Samantha Henig, who I love a lot, and I just read the Meh List. MEHH List. Ha. And I think it’s fun. Especially the last one. Ha! Oh dear. You’re so funny, you’re so cute, you’re so wonderful. Love. Proud. Proud to love you. Bye.

She appears to have forgotten her concerns from last week about this being the final Meh List and what that means for my performance assessment, much like she has forgotten all but the vaguest notion of Citronella.

Samantha Henig is the web editor for the New York Times Magazine

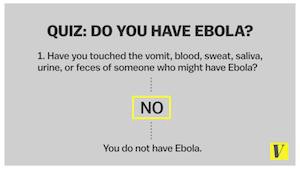

"Calm Down," the Movie

A group of young people return from a week in a remote and disconnected cabin only to find their home city in chaos. Ebola has arrived, and it has gone airborne. Panic and grief overtake these old friends, who don’t know what to do. One suggests hiding in her apartment, a converted loft with steel doors, sealed windows, and some canned food. Another offers up his uncle’s home in the countryside. One friend, who had been silent since that first abandoned toll booth, interrupts. “We must find him. He can’t think we’ve forgotten.”

“Who?” asks the woman with the loft. “We don’t have time!” By now even the sirens have gone quiet.

The friend looks at his feet, shakes his head, and then holds up his phone.

The "Times" Opinion Curse

On June 10, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., Mark Thompson and Andrew Rosenthal, along with New York Times Op-Ed columnists Charles M. Blow, David Brooks, Frank Bruni, Roger Cohen, Gail Collins, Ross Douthat, Maureen Dowd, Nicholas Kristof and Joe Nocera, celebrated the launch of NYT Opinion, the new stand-alone Opinion subscription and mobile app, at NeueHouse in New York City.

Other notable attendees: Mayor Bill de Blasio, Lorne Michaels, professional basketball player Jason Collins, Katie Couric, Savannah Guthrie, Charlie Rose, Gayle King, Norah O’Donnell, Mia Farrow, “Orange Is the New Black” creator [sic] Piper Kerman, and Barbara Walters.

This was not just a huge party for a new app. It was an enormous vote of confidence in the New York Times opinion franchise, which the institution reveres and protects at all costs.

Now, a story dated October 1st:

Mr. Sulzberger and Mr. Thompson said that even with the cutbacks — 100 positions comprise about 7.5 percent of the newsroom staff — The Times would continue to expand and invest heavily in initiatives that supported its growth strategy, like digital technology, audience development and mobile offerings.

But they also said they had decided to wind down NYT Opinion because it had not drawn a substantial audience. And while praising NYT Now, a new app aimed at younger readers, they said that as a lower-priced subscription offer, it had not proved as popular as they had hoped.

As it “winds down” the Opinion app has a total of 85 ratings in the App Store — just six for the most recent version — and a handful of reviews, most of which fall into the categories of “mysteriously positive and design-focused” and “somewhat annoyed.” According to an internal memo from Arthur Sulzberger and Mark Thompson, “it hasn’t attracted the kind of new audience it would need to be truly scalable.”

Framing this as a “scalability” issue makes it sound like a tech problem, an app problem, or an internet problem. That’s not what this was — NYT Opinion was an interesting piece of software run by talented people but built around an opinion franchise that finished accumulating new fans a decade ago — a franchise whose leader reports directly to Art Sulzberger, not executive editor Dean Baquet. It was a four-month test of the draw of the Times star opinion writers on their own, without the benefit of context or momentum or years of reader habit and loyalty. The results were clear, just as they were in 2007 when readers refused to pay for* Times Select: Given the opportunity to pay six dollars a month for greater access to Thomas Friedman, Charles M. Blow, David Brooks, Frank Bruni, Roger Cohen, Gail Collins, Ross Douthat, Maureen Dowd, Nicholas Kristof and Joe Nocera, people with smartphones resolutely did not. The continued existence of the Opinion app would have been an embarrassment to the paper’s biggest names and therefore it had to die.

The revamped Opinion section of the website will live, which makes some sense: It’s buoyed by aggressive commissioned essays, often written by well-scouted first-time contributors, that do well on the open internet but that sit and wilt in an app. They’re pieces that are only loosely associated with the Times and its staff; the types of things that people don’t seek out so much as come across. And it’s sad about Now, which is great. It’s less irritating and noisy than Twitter and only a little less immediate. It never really runs out of material, because it doesn’t mind linking out. It’s better than any of the other single-site news apps, the primary NYT app included.

Anyway: “They are all experiments, which we are determined to treat as such: to learn, pivot and, where necessary, make prompt decisions about them,” the internal death notice says. Deep newsroom cuts, 100 people. Pivot.

* Michael Roston of the Times points out that before it was discontinued, Times Select had accumulated 227k subscribers for its archive/paywall product. Perhaps “refused to pay” is strong; people paid, just not enough of them to be more valuable than ad dollars lost to the paywall.

Ancestors Bothered

Marris describes most of Redzepi’s recipes as similarly ‘exotic, oceanic, deep-woodsy, and uncookable’. Serving something as simple as ‘silken fresh cheese and crispy beech leaves’ requires pickling beech leaves in a vacuum pack with apple balsamic vinegar for at least a month…. one wonders what our remote ancestors would think of this culinary fad.

I don’t know, what would they think of this essay? What would they think of the computer you made them read it on? Or did you go back in time to show it to them? In which case: Are your arms and legs fading away? Are you disappearing from family photos? “Our remote ancestors” would see the entire modern world as a threat and probably attempt to either escape or destroy it, I think is the answer. Or they might just say, “wow, nice, look at all this food.” As far as demonstrations of absolute dominion over the world and its history, voluntarily eating bark ranks as pretty harmless.

New York City, September 29, 2014

★★★ The sun came straight along the cross street, hit the mirrored tower, and came back barely diminished, putting a blinding two-way glow on everything. The subway platform was warm enough to raise a sweat, if one was in a hurry and the next train was not. The clouds had been subtly lovely at dawn, then opened up, and now, downtown, closed again. A damp, pearly Hong Kong light lay on everything. Though the day, the brightness through the window right behind the new office seat slowly failed, till it was time to dig into the tastefully recessed wiring pocket and figure out where to plug in the desk lamp. Outside the clouds had gone over to heavy gray, with ugly yellow tinges to the east and west. The air was warm and thick. Sunset was a diffuse and featureless orange-pink glow that spread evenly far up the clouds, then smoothly receding and fading down to purple.

Cloud Nothings, "Now Hear In"

From Here And Nowhere Else, which came out in April, a video for the album’s most energetic track — one of the few that might have fit in on the very fun and very catchy self-titled album, from 2011, which has apparently been reassessed as the product of an “introductory phase” that should now be “eradicated.” RUDE.

Where Should We Bury the Dead Racist Literary Giants?

by Noah Berlatsky

H.P. Lovecraft is widely acclaimed as one of the great masters of horror. He created the Cthulhu mythos, a pantheon of hideous eldritch deities lurking outside of time that occasionally peep through into our reality to wreak havoc and drive men mad, is credited with inventing weird fantasy; and was a major influence on everyone from Stephen King to Alan Moore. He was also, like many authors of the early twentieth century, really racist.

In a famous letter from a stay in Brooklyn during the nineteen twenties, Lovecraft described the ethnic diversity around him in the same language he used to describe nightmare horrors:

“The organic things inhabiting that awful cesspool could not by any stretch of the imagination be call’d human. They were monstrous and nebulous adumbrations of the pithecanthropoid and amoebal; vaguely moulded from some stinking viscous slime of the earth’s corruption, and slithering and oozing in and on the filthy streets or in and out of windows and doorways in a fashion suggestive of nothing but infesting worms or deep-sea unnamabilities.”

Lovecraft isn’t talking about monsters or demons there; he’s referring to non-white people, whom he sees as “infesting worms” “pithecanthropoid and amoebal.” He expresses similar sentiments in the poem below, which doesn’t seem to have been published, but which he apparently sent to friends:

When, long ago, the gods created Earth

In Jove’s fair image Man was shaped at birth.

The beasts for lesser parts were next designed;

Yet were they too remote from humankind.

To fill the gap, and join the rest to Man,

Th’Olympian host conceiv’d a clever plan.

A beast they wrought, in semi-human figure,

Filled it with vice, and called the thing a Nigger.

These less public works aren’t outliers in Lovecraft’s oeuvre. As Phenderson Djeli Clark wrote at Racialicious, “Lovecraft’s racial biases ran deep and strong, as evidenced by his stories — from exotic locales with tropic natives lacerating themselves before mad gods in acts of ‘negro fetishism’ (Call of Cthulhu), to descriptions of a black man as ‘gorilla-like’ and one of the world’s ‘many ugly things’ (Herbert West — Re-animator).” This presents Lovecraft’s enthusiasts with a dilemma. How do you love a writer whose works are thoroughly infested with racism?

In a post that provoked some controversy earlier this year, Daniel José Older argued that the best thing to do with Lovecraft was to de-canonize him — implicitly relegating him to the same sort of backwater reserved for such works of racist pulp as Thomas Dixon’s contemporary, and mostly forgotten The Clansman. For Older, Lovecraft’s racism is central to his themes and his horror; his vision of hapless New Englanders besieged by degenerate chthonic monsters is insistently racialized, and the terror of the non-human in his work is inseparable from the eugenic disgust at the less-than-human.

Earlier this year, Older created a petition to get rid of the Lovecraft bust that is given to winners of the World Fantasy Award, one of the major awards given to authors of speculative fiction, along with the Hugo and the Nebula. Older suggests that the bust could be replaced with one of the widely respected science-fiction and fantasy author Octavia Butler, who is known for her thoughtful approach to issues of race and gender in stories like”Bloodchild” and the novel Kindred. Among the supporters of his petition are the acclaimed sci-fi/fantasy writer Nnedi Okorafor, who won the award in 2011 (and wrote about how upsetting it was to have Lovecraft glowering from her shelf), and previous nominees Kat Howard and N.K. Jemison.

Unsurprisingly, Lovecraft enthusiasts don’t support the idea that his work should be cast into the howling darkness. In August, S. T. Joshi, probably the world’s leading Lovecraft scholar, bristled at the suggestion that Lovecraft’s racism should disqualify him from reverence. According to Joshi, only five Lovecraft stories have racism “as their central core.” Besides, he argues, it is “a tad risky to judge figures of past historical epochs by the standards of our own perfect moral, political, and spiritual enlightenment.”

But Lovecraft’s racism isn’t some sort of quaint relic that can easily be bracketed off from his writing as a whole; it’s the engine for the loathing and nameless dread that are his trademark. Perhaps the best example is one of Lovecraft’s greatest novellas, “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” from 1936. In the story, the unnamed narrator is touring New England to view unusual architecture when he happens upon Innsmouth, a coastal town with a bad reputation. When he approaches one of the residents of a nearby town to find out why everyone hates Innsmouth, he learns that the inhabitants of the cursed village have been mating with South Sea Islanders. According to the local source, “the real thing behind the way folks feel is simply race prejudice — and I don’t say I’m blaming those that hold it.”

Lovecraft makes it clear that the “race prejudice” is justified, and that people are right to recoil at miscegenation in Innsmouth: The islanders are not just from out of town, they are amphibious creatures — the spawn of strange and evil gods. As the result of their interbreeding, the residents take on a fish-like appearance which is referred to in the story as the “Innsmouth look.”

His oddities certainly did not look Asiatic, Polynesian, Levantine or negroid, yet I could see why the people found him alien. I myself would have thought of biological degeneration rather than alienage.

Lovecraft, through the narrator, disavows the various racial groups in order to subsume them all into a single “alien” Other — and then link it to degeneration and animality. The residents of Innsmouth are foreign, which is expressed not through residence in a different place, but rather through their blank, oozing orginlessness; they are an indistinguishable mass of subhuman monstrosity. Later in the story, when the narrator flees in desperation, with the Innsmouth hordes at his heels, he catches a nightmarish glimpse of his pursuers:

I could see them plainly only a block away — and was horrified by the bestial abnormality of their faces and the doglike sub-humanness of their crouching gait. One man moved in a positively simian way, with long arms frequently touching the ground; while another figure — robed and tiaraed — seemed to progress in an almost hopping fashion….they passed on across the moonlit space without varying their course — meanwhile croaking and jabbering in more hateful guttural patois I could not identify.

The “hateful guttural patois” is unidentifiable; the world outside of the United States — or New England? — is a confusing, loathsome monstrosity. Non-white people don’t exist as humans, but as symbols, or markers, of a grinding fear lodged in the white hindbrain — a fear that somewhere, out there, someone else exists. Lovecraft’s timid protagonists, forever striving to not name the nameless terror before them for fear of going mad, are pitifully neutered expressions of genetically validated white manhood whose fear and weakness inevitably turns into a familiar orgy of violence: After the narrator escapes from Innsmouth he notifies the authorities, who come into town and exterminate everyone.

The story famously ends with the hero discovering that he has Innsmouth blood in his own genealogical tree. At first, horrified, he plans to kill himself, but then slowly begins to like the idea of becoming a fish monster. “I feel queerly drawn toward the unknown sea-depths instead of fearing them.” The narrator determines to rescue his similarly Innsmouth-changed cousin, and the story concludes with one of the most beautifully written paragraphs Lovecraft ever penned:

I shall plan my cousin’s escape from that Canton mad-house, and together we shall go to marvel-shadowed Innsmouth. We shall swim out to that brooding reef in the sea and dive down through black abysses to Cyclopean and many-columned Y’ha-nthlei, and in that lair of the Deep Ones we shall dwell amidst wonder and glory for ever.

The narrator, and by extension, Lovecraft, become the racial degenerate monster, and the experience is ecstatic, religious, sensual; racism turns into fetishization. It’s as if John Calhoun woke up one morning and suddenly found himself transformed into Gauguin, or Eric Clapton. Lovecraft’s repulsive non-white world is a threat. But it’s also an opportunity; a dream that, someway, by some nameless horror, he can himself be debased.

Reading “A Shadow Over Innsmouth,” it’s clear that Older is right; Lovecraft’s racism is absolutely central to his work. His monsters are racist fever dreams; his terror of degeneration is eugenic; the disgusted desire for the loathsome thing that concludes “Innsmouth” is the disgusted desire of Orientalism. Given that, WFA should find a different bust for their award.

At the same time, focusing on race in Lovecraft can also lead to a greater appreciation of his work, and a better understanding of its horror. Joshi may think he’s protecting Lovecraft’s legacy by minimizing the role of race in his stories, but the truth is that, to the extent that Lovecraft is still meaningful, it’s in large part because of his portrait of his own racism. Lovecraft isn’t a great artist despite being a racist, as Joshi would have it. Nor is he a lousy artist because he’s a racist, as Older says. He’s a great artist and he’s a racist: Lovecraft’s world is one in which racism poisons everything, in which the fear of anyone who isn’t white is so overwhelming that it fills the seas and the skies and everything in between with gibbering demons and cosmic despair. The bleak, clotted hatred with which he renders that world is precisely what makes his work valuable.

Noah Berlatsky edits the online comics and culture website the Hooded Utilitarian, and his book on the original Wonder Woman comics will be out in early 2015.

Photo by batwrangler

The New Ethnic Media

The New Ethnic Media

Taffy Brodesser-Akner on Paula Deen’s rapid and basically unfettered comeback, after her brief banishment from public life:

An investment in Paula Deen conveys a deep understanding of America’s political temperature and where we’re headed: that Paula’s comeback isn’t about forgiveness — it’s about standing her ground…

First, there’s the digital network. Then there’s the 20-city tour of a cooking show with the whole Deen family; according to the venues I checked, which were large, the tour sold quite well. She’s out there reminding everyone that she still exists, that she just won’t be subject to the same scrutiny and censorship she once was. She’s gone rogue, she has, and nobody will tell what she can’t say ever again. One man on the boat was not a particular fan of hers even just a year before, but when he heard that Food Network had dropped her, he canceled his Food Network magazine subscription, bought a Cooking with Paula Deen one, and joined her on the cruise, because if you can’t say what you’re thinking, what good is a democracy?

Compare with Sarah Palin’s online video network:

The Sarah Palin Channel, which went live on Sunday, bills itself as a “direct connection” for the former Alaska governor and GOP vice presidential candidate with her supporters, bypassing media filters.

Palin says she oversees all content posted to the channel. This will include her own political commentary. Other features for subscribers include the ability to submit questions to Palin and participate with her in online video chats, she says in an online announcement.

Membership is set at $9.95 per month or $99.95 for a year. Active-duty military personal can subscribe for free.

That last writeup came from the website of The Blaze, which is attached to the video network that kicked off this whole trend — a network that has grown significantly:

[Glenn Beck is] convinced his future is in producing mainstream entertainment — and if broadened appeal is the goal, there are worse tactics than recalibrating your persona from conservative pit bull to loving labrador.

Of course, Beck continues to drive and echo the popular narratives of conservative talk radio: In recent weeks, he has accused Obama of “legimitizing Jihad,” declared a “race war” in America, and tossed around the word “communist” with just as much gusto and frequency as ever. But whereas two years ago Beck was on the forefront of the right-wing conversation — introducing new villains, crafting new story lines, and making headlines with envelope-pushing rhetoric — now he often runs through the talking points like items on a to-do list before moving on to enthusiastic descriptions of his latest project, and feel-good interviews.

These outlets share a basic form — online video network — and depend on relatively steep subscription fees (the comparison that always gets used is “more than Netflix”). They are fundamentally oppositional: to the mainstream media; to political correctness; to godlessness but also a very particular formulation of uptightness. They are nostalgic for a time when certain people could say certain things without worrying about controversy or shame — they feel like public speech is a minefield, so they’ve made theirs a little more private. Among friends, almost. They long for a wholesome past that they feel has been lost. They are not especially cynical. They are, in effect, a white ethnic media, writing and publishing and broadcasting and performing about the experience of American whiteness as understood by people who genuinely feel that whites are becoming a marginalized minority. Race is not addressed directly in these networks’ contents or containers — identity establishment is left to “urban”-style euphemisms and the projection of a sensibility that is neither explicitly nor assertively white, just inherently white, familiar to whites, deemed important or compelling or novel because it is no longer the norm elsewhere. On this point, they might not be wrong: The “mainstream media,” as they would call it — the default, the center — has reliably expressed white identity for as long as it’s existed. The success of these networks is a sign — a small lagging indicator, maybe — that this is coming to an end.

Don't Forget These 7 Items While Traveling

by Awl Sponsors

Brought to you by KLM Airlines

Those “if only I just remembered to pack that” moments are the worst. Along with bad hair days, horrible cell phone reception areas, and warm salads. To help you avoid that soul-crushing feeling of ‘shoulda-woulda-coulda’, here’s a handy list to check off when packing your bag for your next flight.

1) Photocopies of your passport, ID and credit cards. In the event that your bag is stolen or lost, keeping photocopies of your essential ID’s and cards stashed elsewhere will help make the recovery process a lot faster.

2) Snacks. Don’t be THAT person who spends $10 on a bag of chips on the airport. Bringing some nutritional reinforcement will help you avoid that “hangry” feeling. (hungry + angry…get it?)

3) Phone charger. How hopeless is that feeling when you see that you’re in the red on your smartphone and you don’t have your charger anywhere near you? Avoid missing important calls and texts by packing your charger in your carry-on. There are outlets all over the airport to help juice up your smartphone.

4) Travel pillow. Avoid drooling on the passenger next to you by bringing a comfortable neck pillow that lets you catch up on your ZZZ’s in a socially acceptable manner.

5) Sweater or sweatshirt. If you tend to get cold easily, don’t forget to pack a sweater or sweatshirt in your carry-on so you can have a line of defense against your co-passenger’s AC-blasting habits.

6) Sunglasses. These are probably one of the top forgotten items when traveling, so make sure to pack your sunnies, especially if you want to snooze during a daytime flight.

7) Headphones. You’ll want to give yourself an award for remembering headphones when you hear a baby start to cry somewhere on the flight. Goodbye adolescent screaming, hello Beyoncé.

At KLM Airlines, we have your back as a traveler. KLM offers a unique Lost & Found service at Amsterdam Airport Schiphol. A dedicated team is now on a mission to return items, found by cabin crew on board or by KLM airport staff, to their legitimate owners — as soon as possible. Very often the Lost & Found team is able to surprise passengers by returning their personal belongings before they have even missed them. Despite the challenge of locating the owner, first results show that over 80% of the found items can now be reunited with their owners.

To show how far the Lost & Found team and their tail-wagging secret weapon go, check out this video below.

The Anthem of the Working Stiff

by Casey N. Cep

I don’t know what men are made of, though a song I love begins: “Some people say a man is made out of mud.” Perhaps the dust of Eden got wet with the kiss of the Lord and made mud, and from that Adam was made, but that’s not what Tennessee Ernie Ford meant when he sang “a poor man’s made out of muscle and blood.”

“Sixteen Tons” is the anthem of the working stiff. Ford didn’t write the song and he wasn’t the first to record it, but his version from 1955 has worked its way into the assembly-line-addled ears and labor-worn hearts of workers ever since. Whatever a man is actually made of, saying he’s made of “muscle and blood and skin and bones, a mind that’s weak a back that’s strong” is acknowledging that’s what the world has made him into, and that righteous lament is why the song’s still so popular.

I thought of “Sixteen Tons” the other day while listening to Lorde’s “Royals.” The off-beat snapping in both songs made me realize that if we’re not too busy tweeting the revolution, then we’ll probably be snapping our fingers. The snaps even start to sound kind of menacing, like the tell-tale heart of the working class about to explode, especially when Ford sings, “fightin’ and trouble are my middle name.”

But how did he get there? “Sixteen Tons” laments cradle-to-grave work in the mines. “I was born one morning when the sun didn’t shine,” Ford sings: “I picked up my shovel and I walked to the mine.” It’s a country song that we wish to be decades out of date, but it’s not, instead it’s all too contemporary; there are still millions of people who wake up every day thinking something like “Saint Peter don’t you call me cause I can’t go: I owe my soul to the company store.”

“Sixteen Tons” endures because we are almost all always getting “another day older and deeper in debt.” It is easy to feel, and it is often true, that despite our hard work, the bills unpaid while the debts grow. Ford might have owed his “soul to the company store,” but we owe ours to credit cards or student loans, car companies or mortgage brokers.

You take sixteen calls or file sixteen memos, write sixteen posts or sell sixteen ads, work sixteen hours: you do whatever interval of whatever work you do every day of your working life, and that is what “Sixteen Tons” is about. The song isn’t just a lament for mining, but any kind of exploitative work, which is almost every kind of work.

Country Time is an occasional column about country music.

Casey N. Cep is a writer from the Eastern Shore of Maryland.