Yumi Zouma, "Alena"

Here is New Zealand’s Yumi Zouma with a genuinely relaxing track. It’s a build-and-release song structure, except muted: It doesn’t work you up — it gets your attention and then calms you down.

Relief Sought

“The term of choice for its practitioners is BLARPing — business live action role play.”

New York City, October 7, 2014

★★ Near-identical shadows of torchiere lamps stood in the same place on the same wall in two different apartments, one directly above the other. The clouds knitted together uptown, but were apart downtown for a while. Blue mottled with white became white mottled with gray. Still the afternoon sun found a place over Lower Manhattan it could mostly burn through. By rush hour, the sky overhead downtown was clear and blue; uptown was nearly the same blue, but now it was the blue of twilight on clouds.

Cash and Anxiety on the Weird New Internet

Welcome to ᴄᴏɴᴛᴇɴᴛ ᴡᴀʀs, an occasional column intended to keep a majority of ᴄᴏɴᴛᴇɴᴛ coverage in one easily avoidable place.

Here is something that is not quite missing but also not all the way present in stories about Fusion’s all-star hiring spree: The money. It is not yet clear, from the outside, what Fusion is planning on doing with all its new hires, but they’re getting very good people: Anna Holmes, Dodai Stewart, Felix Salmon, Jane Spencer. Yesterday The Atlantic’s Alexis Madrigal announced that he too would be joining. Madrigal in 2013:

I am an Atlantic person. I love this place. I feel it in my bones. If I open up one of our musty tomes at the office, I can get sucked in for an hour just looking at the ads, or marveling at the eloquence of W.E.B. DuBois. When I look back at old Ta-Nehisi posts or see Fallows in the halls, I can get emotional.

Here is what I understand about the Fusion proposition: Fusion has money. TV money. This money affords its web operation editorial freedom and the ability to ignore the most exhausting parts of the internet (see: Felix Salmon’s Actual Auction Price Calculator), which is huge. Of course this money also affords new hires money, and a chance to work onscreen: The Fusion job discussions I’ve heard about put its offers in an entirely different ballpark than most of its “competitors,” except maybe Bloomberg, which will throw huge amounts of cash at the people it wants.

Anyway, this is great: Talented people get to pay off debt and do work they want. And because of the contrast it creates with the companies more commonly associated with the internet publishing boom. Big internet publishers pay well on their scale, and on modern print scales. But nothing like this.

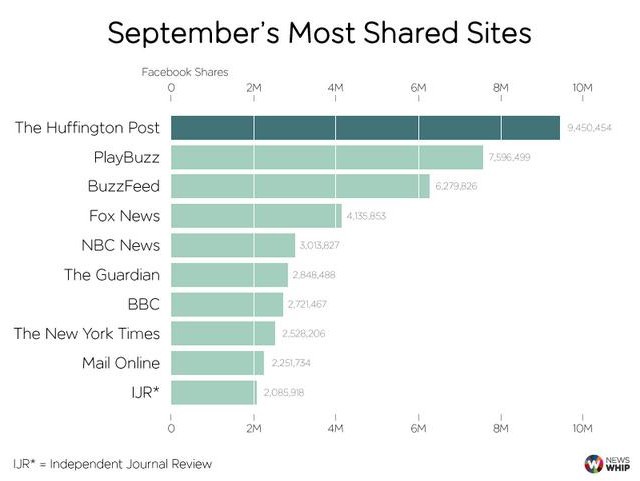

Every month, a company called NewsWhip releases a whole bunch of reports tracking which ᴄᴏɴᴛᴇɴᴛ is performing the best on social media; every month, people cherry-pick the Facebook report for data that is either helpful or not-depressing. Here are September’s top publishers on Facebook:

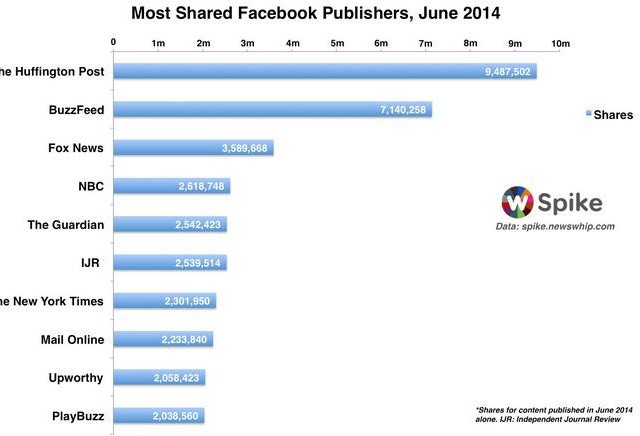

It is possible to look at these and feel OK. Most of these sites are either big news operations growing viral and entertainment arms or big viral and entertainment operations growing news arms. “These are diversified companies doing lots of different things, and it’s working on Facebook, which is good,” you might conclude, generously. Now here’s one from June:

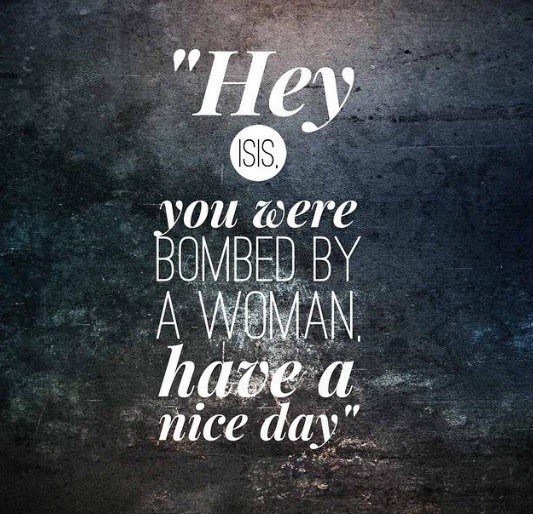

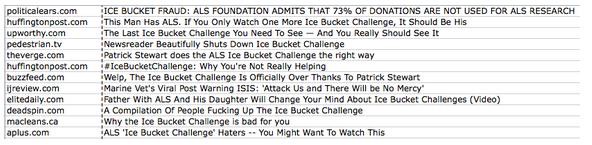

Every month there are hints. Irregularities. Questions? For example, what is a PlayBuzz? (In its current form: An ENORMOUS quiz factory. In June? Who knows, it changes a lot). The Independent Journal Review, which is asterisked in every report that includes it because MEDIA PROFESSIONALS have no idea what it is, is a sort of uncanny conservative Upworthy. One of its recent hits:

Female Fighter Pilot Becomes First to Say: ‘Hey ISIS, You Were Bombed by a Woman, Have a Nice Day

Which you can Google if you want, but which contains this Pinterest-ready graphic:

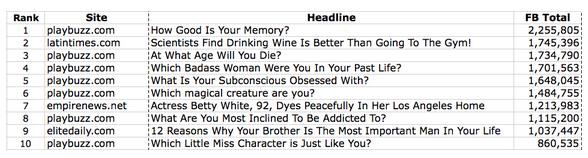

So you see these charts, and you give the internet the benefit of the doubt, but you also wonder. Something seems off. Then you see the most-shared story list:

1. Quiz

2. Thing that is basically false, by a site owned by IBT Media that hosts stories with headlines like “10 Latinas Who’ve Definitely Had Plastic Surgery,” which, unlike most stories on the site, does not carry a byline

3. Quiz

4. Quiz

5. Quiz

6. Quiz

7. A death hoax from a site that is comprised ENTIRELY of fake stories and “satire” intended to be shared by people who don’t realize that it’s satire.

8. Quiz

9. EliteDaily 🙁

10. Quiz

Now, the list for August:

Ice bucket, ice bucket, ISIS. Not a single quiz. What can Publishers Learn From This? A literal interpretation: SUBLIMATE YOUR IDENTITY ENTIRELY, EVERY MONTH, because nothing else works, and the next PlayBuzz or Viral Nova could appear tomorrow and just totally house you out of nowhere.

Another thing you notice if you check in on these reports month to month — which is something that managers at most big media companies do! — is that the share pool isn’t growing that much. The water is rising, yes, but the most-shared site in both June and September, the Huffington Post, stayed steady about about nine million shares. Second place traded but stayed at about seven. Then quickly down to the twos, with a lower threshold of almost exactly two million.

Yet the types of content change every month, not just in subject but in form. This might suggest that some of these formats are less durable than others: If a particular type of share-friendly post worked in June, or July, then why wouldn’t it work in September? Again, this isn’t about changing subjects, but changing containers: Upworthy has been posting similar types of videos for the last two years but its headline templates — or rather, headlines that have tested well — have shifted noticeably.

It’s hard to believe that this is just refinement. One possible explanation: Novel formats fall as quickly as they rise, especially if they contain little of value. Or if they’re just new ways to cry wolf.

Here is a story called “How The New Yorker Finally Figured Out The Internet: 3 Lessons From Its Web Redesign.” The story notes that traffic is “up 23% from a year ago” and says “[s]ince the July relaunch, traffic on NewYorker.com is averaging 10.4 million monthly uniques.” Now, here is a story from May of last year: “April was the best traffic month ever for NewYorker.com, with 10.7 million unique monthly visitors.” Mmmm. Even if you focus on the 23% claim, why not just credit that to the site’s newly opened archives? This piece also seems to overstate the number of posts the site publishes each day.

Anyway: Andy Borowitz.

My labor of love the last two years has been The Magazine, first as its hired hand and then, in May 2013, as its owner. The sad truth has been that, while profitable from week one, the publication has had a declining subscription base since February 2013. It started at such a high level that we could handle a decline for a long time, but despite every effort — including our first-year anthology crowdfunded a bit under a year ago — we couldn’t replace departing subscribers with new ones fast enough. We’re a general-interest magazine that appeals to people who like technology, and that makes it very hard to market. “Pivoting” to a different editorial focus would have lost subscribers even faster.

Long story short: “Our last subscription issue will be December 17, 2014, after which we will discontinue and refund subscription on a pro-rated basis and may produce some ebooks or special projects thereafter.”

Some more local Facebook news: For the last few weeks, Alex Balk’s five-year-old “How To Cook A Fucking Steak” post has been hovering near the top of our live stats. We have a few posts that surge like that from time to time, and Steak is one of them, but this is different: Facebook seems to have… found it. Yesterday we had a handful of stories that were doing “well” by our standards, but that were all less popular than Steak. We don’t know WHERE on Facebook Steak resurfaced, or why — some horrible Thug Kitchen effect? — but it just keeps on going. To be clear: We are glad that more people are interested in learning How To Cook a Fucking Steak. But this will end at some point which we cannot predict and, in retrospect, will not be able to explain. And then it will happen again. Drink!

The YA Books No Adult Should Read

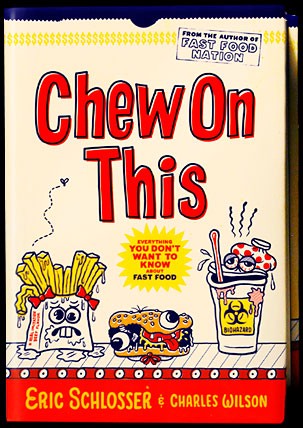

A thing I compulsively do after I pick up my Kindle, but before I start actually reading anything, is browse through its bookstore. Even though I rarely buy books from Amazon in order to avoid contributing to the downfall of publishing as we know it or whatever, I have made at least a few random purchases, like Eric Schlosser’s Chew on This, which, in the fog of early morning and the kind of gross, glowing wintergreen glaze atop the Kindle’s black-and-white E-Ink pages, seemed like a sequel or an update to Fast Food Nation, which I had never read in its entirety. I was immediately struck not just by how repetitive of Fast Food Nation it seemed, but by how jarringly simple the writing was, so I stopped reading it.

It turns out there was a reason for this: It’s actually a child’s version of Fast Food Nation, and it has sold more than three hundred thousand copies, making it, according to the New York Times, one of the earliest successes in a newish genre, YA non-fiction. This format, in its present form, is largely constructed from re-constituted, infantilized versions of existing non-fiction, like Laura Hillenbrand’s World War II book, Unbroken, but stripped of all its horror.

While it is perfectly fine to produce non-fiction books explicitly designed for children, or even for harried adults who deem themselves too busy to read more complex non-fiction (I guess), what’s startling is that these are fundamentally lesser versions of extant books which are meant not solely for recent human spawn:

Publishers have another potential audience in mind for these books: adults who have embraced children’s fiction and may be too intimidated or busy to read a 900-page nonfiction tome. “Adults are now so used to reading young adult books that there may be some nice crossover,” Ms. Horowitz said.

The recent debate over whether adults should or shouldn’t read YA fiction grew exceedingly tedious, exceedingly quickly, and does anyone even care anymore since the latest trailer for the new Hunger Games movie came out? But the notion of fully grown persons reading modified versions of adult non-fiction books that aren’t just condensed or simplified or shortened (imagine a Vox books imprint!), but have been fully adapted for children, is truly bizarre: These are people willfully shielding themselves from the fullness of bodies of information that already exist, in order to not be bothered by the more grim or gory or complex details of history — which have already been collected and presented in a given work. This is ordering pizza and saying to hold the bread parts; a hamburger but just the bun and some lettuce and ketchup so it’s not even a gluten thing; pornography but without naked bodies or even a hint of sex. As much as one may chafe at the notion of somebody telling someone else to not read something — read YA novels, who cares! — chastising somebody for picking up D Day instead of The Guns at Last Light feels less like than finger-wagging than the performing one’s duty to combat willful ignorance.

The Artist Is Present and Also a Robot

Between 2004 and 2008, I worked as a video editor in Hollywood. This description comes with plenty of qualifiers: It wasn’t a job with any artistry or excitement (it was, as I described it to curious/confused parties back then, “industrial editing”). The motto of the company I worked for was “Know Better,” and its logo looked eerily like an Illuminati eye; it sold itself as a way for corporations/PR companies/freelancing-citizens-full-of-vanity to amass knowledge about their place in the business world through the monitoring of media. To do this, it recorded TV and radio broadcasts from around the country, and resold commercial-free chunks of said broadcasts to the as-yet uninformed. Need to see how your opposition is being perceived by CNBC’s Jim Cramer? We got what you need. Want a shot of you catching that foul ball at the game? Give us a call.

When I was first hired, there was an editing staff of twelve. We edited how teens did in the nineties: two VHS decks, lots of trial-and-error. Already, by 2004, the cracks in the company’s model were already evident, as the introduction of live-streaming and TiVo meant ambitious interns could accomplish what we were charging top dollar for. When YouTube hit, you could remove the ambition, and the intern, entirely. If an exec wanted to see how local Topeka news was covering his sex scandal, all he needed was an Internet connection and a few keystrokes. (Since the branch I worked at was based in Hollywood, in the same building where Larry King’s suspenders were filmed on a nightly basis, the most common requests were from movie studios wanting compilations of quips and anecdotes and fluff pieces that aired during the promotional round of their latest blockbusters. We also catered to Ron Jeremy, who’d forgo the custom of splurging for a delivery service and personally schlep into the office, once a month or so, to collect a mixtape of his mentions; personally, I worry for his surely-hermetic state following the invention of Google Alert.)

Midway through my term, the company came to understand its place in the world, and dumped the VHS decks for an expensive digital encoding system. Soon, we were no longer wasting time fast-forwarding through tapes; we wasted time surfing the net as the combination of fewer orders and quicker output times led to six hours of downtime per shift. Among other things, this allowed me to become adept at flicking playing cards into a hat. In 2011, the company filed for bankruptcy. It had outlasted its usefulness, and was summarily dispatched by the cold force of free market evolution. This is how progress works.

I first learned how to organize words into some kind of structure that people might want to read by writing recaps for my fantasy baseball league. For those who haven’t delved into the great wide world of fantasy sports — if you haven’t, you’re quickly becoming a minority — the basic concept is this: Fantasy owners pick real-life players from professional sports teams to be a part of their “fantasy roster.” When those players do something in real-life games, like hit a home run or throw a strike-out, the fake team reaps the benefits.

The average league consists of between eight and twelve “owners”; the specific league I wrote recaps for tended towards the higher end of that spectrum. It also utilized a head-to-head scoring system, meaning that each fantasy team played a different team each week, and whichever one earned the most points won. (This is in direct opposition to the “roto” variety of fantasy sports, where everyone plays everyone else at all times, like a golf or bowling tournament; this is better at determining the actual value of teams because it removes luck as a variable.) Head-to-head is the annoying ingrown hair of an option that’s been grandfathered in by meatheads who think trash-talking their friends is an enjoyable use of time, have literally nothing of substance to talk to their extended family about, or are scared of numbers because they make their heads hurt. This makes it the ideal venue for personalized recaps regarding an owner’s idiotic managerial decisions and, thusly, their presumed genital malfunctions.

Every Monday morning, I’d sit down for three hours and offer my witty take on the previous week’s fake games for the other people in my fantasy league. Each recap ran upwards of two thousand words — at least seven hundred of which were boner jokes and Billy Madison references. I wrote a bunch, edited very little, and, subconsciously, came to an understanding, however small, of how to write. So I was somewhat disturbed when this email from CBSSports.com showed up in my inbox earlier this year:

More Than $50 Bucks Worth had a week to forget in the WHIP category, notching a 1.56 WHIP. That was the highest WHIP of any team this week. Zach McAllister and Edinson Volquez were the captain and first mate on the good ship failboat. Together they produced a 2.36 WHIP in 14 innings.

The group of words, written by some kind of automated program, were one section of a larger recap that looked at how the teams in my current league were performing. It wasn’t half bad: the stats provided accurate analysis — in this case, that the stat “walks and hits per inning pitched,” which is used to determine how effectively a pitcher has thrown, was dominated by the team “More Than $50 Bucks Worth.” (Another aspect of fantasy sports: the ability to name your own team, which leads to plenty of jokes that are so insidery it makes Jimmy Fallon look like Charlie Rose.) And while a quip like “good ship failboat” isn’t the most advanced joke around, it’s quite good for a robot. As someone who makes money turning letters into words into sentences into things beyond that, it’s also unnerving.

CBSSports.com is one of the most popular destinations for owners to host their fantasy league. A host takes care of the automated grunt work of fantasy leagues, like tracking which player is on what team and calculating up-to-the-second stats. There are many, many, many free options available, but CBS gets “millions of players” to spend upwards of a hundred and eighty dollars a year to essentially do the same thing by offering premiums with their product, like the ability to use their server to perform a start-of-season online draft in real time, or their private chat rooms and message boards to “trash talk” your opponents. One of the newer perks is automated recaps.

“We’re taking data and creating millions of stories,” Jonathan Dube, the General Manager of CBSSports.com, told me. “That would be impossible for individual journalists to do.” (Not to mention, boring as hell.) “The idea was to use technology to examine the data and produce effective ‘journalism,’ so you can read about it the same way you’d read about a real sporting event,” he continued. There’s even an option for a fantasy team owner to email answers to questions, which are spit into the algorithm as “quotes,” producing fake interviews. “What we do is take fantasy sports and make it real through storytelling,” Dube said.

That storytelling looks like this, a more recent recap from CBSSports.com’s fantasy football service, which shows the evolving capabilities of the program:

After losing three straight games, Coach Rick Paulas’ squad finally had enough. Oakland Upsides got past Pico Burros, winning 111 to 105.

Oakland Upsides got off the schneid with this win. They now sit at 1–3. The loss drops Pico Burros’ record to 2–2.

Blair Walsh tweeted this week that he “really does like winning”, and helped Coach Paulas to share the feeling. Although Oakland Upsides had plenty of players step up in the win, Walsh was just a bit ahead of the others, putting up 17 points. That was the most that any kicker collected this week.

They’re not only putting my name in there, they’re pulling quotes from Twitter. Couldn’t the algorithms and “interviewing” methods used to create these fantasy reports be used for real games too? I asked Dube. “It’s certainly possible,” he said. But Dube, who once worked as a freelance reporter for the New York Times, doesn’t think that real writers have anything to worry about. “Automated stories could not approach the full creativity or expertise of human writers,” he said. “I don’t envision a day when an algorithm is named Fantasy Sports Writer of the Year.”

In 2011, the computer software company Narrative Science released a program called StatsMonkey. It took simple box scores from sporting events and created accurate and informative prose recaps, without human assistance. Behold, the machines:

UNIVERSITY PARK — An outstanding effort by Willie Argo carried the Illini to an 11–5 victory over the Nittany Lions on Saturday at Medlar Field.

Argo blasted two home runs for Illinois. He went 3–4 in the game with five RBIs and two runs scored.

Illini starter Will Strack struggled, allowing five runs in six innings, but the bullpen allowed only no runs and the offense banged out 17 hits to pick up the slack and secure the victory for the Illini.

StatsMonkey even once indisputably wrote a better recap than a human: In 2011, Will Roberts, a pitcher for the University of Virginia, threw a perfect game against George Washington University, only the eighth such performance in NCAA Division I history since 1957. Yet, the recapper for GWSports.com didn’t mention the twenty-seven-up-twenty-seven-down feat until the penultimate graf of his story. When Deadspin read the recap, it thought the deep interment of the lede was possibly a failure of robo-recapping software. Turns out, it was simply a human trying to get a jump-start on his copy and failing to rewrite after the narrative of the game shifted. Narrative Science took a stab at their own recap by plugging in the game’s box score; their robot mentioned the rare perfect game in the first sentence.

When Kristian Hammond, the co-founder of Narrative Science, was asked by Wired if his company’s tech would make human recappers obsolete, he used the same explanation as Dube to downplay the possibility: The tech’s only intended to perform menial jobs with such low levels of interest they wouldn’t be worth sending out actual human resources. For instance, Little League games:

“Have you ever seen a reporter at a Little League game? That’s the most important thing about us. Nobody has lost a single job because of us.”

While sports — baseball, in particular, where an entire game can be condensed into the heralded space of the box score — certainly lend themselves to a certain kind of journalism-by-raw-number-crunching, they’re not exceptional in that regard; substitute dollars or drone strike casualties or political polls for RBIs and WHIP, and you essentially have many of the kind reports you’d find in Bloomberg, AP, or FiveThirtyEight.

The recapping technology used by CBSSports was developed a few years back with a Chicago-based narrative generator startup, Fantasy Journalist. Earlier this year, it changed its name from the niche moniker to the more sweeping infoSentience, which reflects its newly heightened ambitions to creater a wider ranging artificial intelligence with broader applications. “Our initial goal was to just do a great job creating recaps for fantasy sports,” Steve Wasick, the president of the company, told me. “However, the technology that powers these recaps can be applied elsewhere. The question is: what business and organizations have large amounts of data that they would like to have instantly summarized? We think the answer covers a ton of potential applications.”

In 2013, Narrative Science has released Quill, billed as a way for companies to forgo the confusion/boredom that comes with trying to deliver data to their employees. Sell paper clips? Plug your spreadsheets into Quill, and it’ll regurgitate a narrative report suggesting which markets to ignore and which to focus on, in relatively plain English. An even newer version of the program, Quill Engage, takes data from Google Analytics and outputs a report in understandable prose that tells the webmaster, or whatever we now call the people in charge of websites, how many Kim Kardashian posts did well last month and, therefore, how many should be scheduled this month to hit traffic goals. (Just imagine two tiny clusters of robots: one producing algorithmically generated content and one analyzing traffic, each feeding into other, producing a perfect feedback loop of infinite linkbait. It’s not very hard.)

While algo-writing technology may seem brand new, Narrative Science and infoSentience already have plenty of competition. Automated Insights provides a program that is, according to their site, “like an expert talking with each user in plain English.” (In June, the Associated Press began using the program to produce “a majority” of their U.S. corporate earnings stories.) Unlike other producers of robo-content, who sheepishly suggest human creativity can’t be disrupted, the Dallas-based Yseop bills itself as “disruptive technology” — that is, technology which will displace an existing market. Yseop provides executive summaries, product descriptions, fact sheets, and even biographies based on a person’s LinkedIn account, all written in milliseconds, and in languages other than English, if you’d like.

The standard defense when it comes to algo-writers not taking human jobs — the ones extolled by Dube and Hammond, that machines will never supplant humans because we have consciousness, is great for writers to use to tuck ourselves in at night. But none of us can be entirely sure of the consciousness of even other humans. That the consciousness of a human can’t be proven, nor can the consciousness of a computer be disproven, highlights the falseness of a “conscious” writer having a leg up on an algorithm. Words on a screen don’t have to be created with consciousness, or with expertise and creativity. They just have to display the qualities of expertise and creativity — which is to say, the organization of letters and words and paragraphs in a specific structure in a way that seems like thinking. Computers have always been good at organizing things, and they’re only getting better.

In 1950, mathematician Alan Turing developed his famous test to figure out when artificial intelligence has reached the point of being indistinguishable from human intelligence. It works like so: A handful of judges get together and text-only chat with one human and one computer. They then have to decide which is the human, which is the computer; once a third of the judges are fooled by the machine, legitimate artificial intelligence has been created. A few months ago, a computer finally passed it. Oh, sure, there are all sorts of caveats to it — including that the program pre-declared it was a 13-year-old boy and English was “his” second language, which sets the bar low for judges’ interrogative techniques — but even if you want to hold onto the uniqueness of humanity for now, the test will certainly be defeated within your lifetime.

Maybe this isn’t such a bad thing. There hasn’t been a day since I left my Hollywood editing job when I’ve missed it. Oh, sure, the social aspect was nice, and having healthcare and full dental was pleasant. But the job sucked, even with the occasional Ron Jeremy sighting. Maybe all the robo-writer rise will do is give us human-writers more time to work on more artistic ventures, like lengthy novels, or whatever the hell this piece is. Maybe we’ll be forced to leave the comfort of our home offices and develop legitimate skills with actual earning potential, like first aid or the ability to teach the next generation. Maybe swapping out thousands of “industrial writers” who produce technical documents, or long lists about TV shows from twenty years ago, for those who can actually assist the progress of humanity isn’t the worst thing to happen.

Or maybe our jobs will just shift: If these robo-writers are a digital update on that famed room of infinite monkeys pounding on their infinite typewriters, a human presence will still be needed to sift through the mountainous pile and find the Shakespeare. Update your resumes accordingly.

This article was written by a sex robot.

The Starbucks Booze Worst-Case Scenario

Does this Williamsburg coffee shop owner sound a little paranoid? Sure:

Bell, who leaped into action this week after finding out about Starbucks’ plan to sell alcohol, said granting the chain a liquor license could embolden the company to seek a more and more. She said there could end up being a Starbucks-affiliated business on every corner, making it one of the only places to go.

It does not seem to be Starbucks’ plan to open a “Starbucks beer garden, a Starbucks sports bar,” or anything quite like that. But I do think the Starbucks alcohol initiative — there are locations with a “Starbucks Evenings Menu” in Chicago, Portland, Los Angeles and Atlanta — represents something potentially big and, for a particular type of establishment, ruinous.

In some towns, bars are holdouts — some of the only non-chain (or at least non-national-chain) establishments available to patronize. Chicago and Portland and Los Angeles and Atlanta are not these towns, so while they might be good markets for Starbucks to test out new concepts for viability, they’re poor markets for understanding what effects the introduction of Starbucks wine bars might have on smaller, more fragile commercial ecosystems. They can absorb a lot.

Anyone looking to understand chain-booze paranoia should look to the UK’s experience:

[Large pub companies] have about one-third of Britain’s pubs in their portfolios. Punch and Enterprise — two of the largest of an estimated total of about 50,000 pubs in England, as of 2012 — hold about 4,000 and 6,000 leased or tenanted pubs, respectively, and are trying to cut debt built up through acquisitions during the boom years of the 1990s and early 2000s, before the recession.

Many pubs are owned outright by these companies; others are operated in a strange sort of franchise mode, in which they are “tied” — they pay both rent on the building and “wet rent” on drinks, the availability and price of which are decided by large pub companies who are able to charge significantly above-market prices. The effect can be depressing in subtle ways: You might only realize that you’re in a chain pub after you see a food menu with a familiar color scheme, or when you spot a drink special that you’ve seen before. This is just as if not more likely to happen in a small town, in a beautiful old building, as it is in a new place in a large city. It’s a strange feeling, to realize that the establishment you’re in is concealing its identity out of savvy or shame, a little like finding out that your fancy soap in the over-designed bottle is sold by the same company that makes the bleach under your sink. (The biggest British pub companies, incidentally, are currently attempting to expand into coffee. Every chain wants to be every other chain.)

Anyway: The alt-contemporary Starbucks nightlife dystopia is neither currently real nor particularly close. (Chain fast-casual restaurants are probably a much larger threat to independent American bars than Starbucks will ever be, and might have already won — they can materialize out of nowhere with a decent, inoffensive bar experience and a much better food experience than their smaller booze-centric competitors.) But a limited version is plausible: A near-future situation in which Starbucks successfully turns its thousands of centrally located coffee shops into safe and predictable places to meet someone and have a glass of wine and some olives and cheese or whatever. Basically, Starbucks could conceivably corner the Tinder/Match/OkCupid first-date market, or the “after-work-one-or-two-drink” market. Which is no small thing! For some people, at some stages of life, in some places, consolidating these morning and evening options into one location might represent near-total social capture. Have you ever been to Starbucks twice in one day, as the company’s loyalty programs aggressively encourage? It doesn’t feel great. Now imagine that feeling with depressants.

Ban Cars from Central Park

The mystery of the bear cub found dead on Monday in Central Park is one step closer to being solved: It was revealed on Tuesday that she died after being hit by a car.

The state’s Department of Environmental Conservation announced that the results of a necropsy showed that the cause of death was “blunt force injuries consistent with a motor vehicle collision.”

Sylas, "Shore"

A relaxing synth bath from London duo (and Brian Eno collaborators) Sylas with a sound that unfolds, with a little volume, into something lush and expansive. Try “Hollow,” too.