Two Minutes of Walking on the Internet as a Woman

Here is a video that will surprise only men. In it, a woman walks through the streets of New York City, briskly and silently, eyes ahead. Over the course of ten hours she is approached, catcalled and harassed dozens upon dozens of times, all in broad daylight.

The effect is powerful and useful — “10 Hours of Walking in NYC as a Woman” is a succinct answer to anyone who asks, incredulously, if street harassment is really that bad. People who couldn’t see for themselves — the ones who needed to, at least — now can.

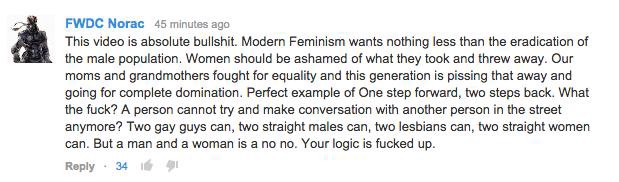

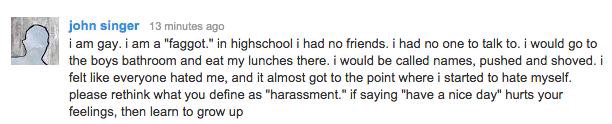

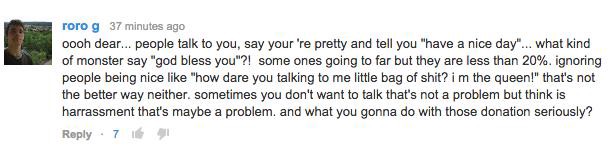

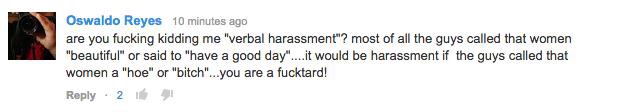

But the video works in two ways: It’s also a neat portrayal of what it is like to be a woman talking about gender on the mainstream internet. This became apparent within minutes of publication, at which point the video’s comment section was flooded with furious responses. The following are all “Top Comments” as determined by YouTube’s viewers and voting system — this is what outwardly appears, among people who chose to engage with this video, to be a consensus (most dissent is voted into oblivion). It is a VAST MAJORITY. Starting with the very top post:

(The subject of race is handled just as thoughtfully.)

A great number of men, online and off, understand feminism as aggression — they feel as though the perception of their actions as threats is itself a threat. In other words, they too believe that unsolicited public attention is inherently aggressive, but only when that attention takes the form of criticism, and only when it comes from women. They live this belief on the streets, where they are nearly unaccountable, and argue it online, where they are totally unaccountable. And they are everywhere! They are just as bad as people say! You don’t even need a hidden camera to see them.

A Modern History of Thirst

by Brendan O’Connor

We need water. And maybe somebody’s daughter. — The Who, “Water”

Recently, in a story about brands and hashtags, the New York Times defined a word.

The effort to co-opt cool can backfire, Mr. Roan said. When someone is “watching a topic that’s trending and then whips up some contrived way to get their voice in that conversation, it’s very predatory and a super-false way to speak,” he said. Or worse: “It reeks of thirst,” he said. (We looked it up, and “thirst,” in this case, means “desperate.”)

This definition may or may not come from UrbanDictionary.com, where the top entry for the word ‘thirsty’ is dated to 2003 and contains two definitions. The first is, “Too eager to get something (especially play)”; the second, merely “desperate.” Ten years later, another user defined thirsty as “The need to gain fame and admiration through social media,” specifically “by posting ‘selfie’ pictures to boost the self esteem.”

Now, not to universalize anyone’s experience, but one of the things about having a living human body is that there are certain functions with which we are all necessarily familiar — one of those is the physical imperative to imbibe water. If we don’t have water, we die. To one degree or another, everyone is familiar with this bodily phenomenon, which, as far as shared language is concerned, makes for a powerful, experiential reference point.

In this sense, to be “thirsty” is a natural state of being; to describe someone in this context as “thirsty” is not a value-judgement — or it is, but only in so far as the state of being “thirsty” is reflective of the bodily state of being dehydrated. But calling someone “dehydrated” doesn’t roll off the tongue in quite the same way as calling someone “thirsty.” “’Thirst’ sounds gross as a word,” one friend told me. “It slithers around in your mouth.”

Like many colloquialisms, however, the word’s meaning has changed both over time and depending upon whose mouth it is slithering around in. On the hook to “Ching-A-Ling,” the lead single to the Step Up 2: The Streets soundtrack released in January 2008, Missy Elliot sings, “Thirsty, baby, bring it over here / See my money maker, do my money maker.” An episode of This American Life from that same month, “Matchmakers,” included a story about an Afghan man’s infatuation. “The young boy get a little bit thirsty, especially in Afghanistan,” a friend of the story’s subject told the segment producer. “When you drink some things more and more, you are not thirsty.” In May of this year, Mariah Carey released her own “Thirsty,” on which she sings, “You used to be Mister-all-about-we / Now you’re just thirsty for celebrity.” The first two examples are evocative of the desire for sexual attention, while Carey echoes the more recent Urban Dictionary definition’s gesture towards the influence of social media on the word’s meaning when she goes on to sing, “So you stunting on your Instagram / But that shit ain’t everything.”

In the cycle of appropriation to which African-American Vernacular English is particularly subject, there comes a point at which a certain kind of person begins to fixate on the fixation of meaning: over the past six months, for example, writers for New York magazine’s The Cut, Jezebel, and BuzzFeed have volleyed back and forth over the meaning of “basic,” culminating in Kara Brown’s proclamation that overanalyzing the word “basic” is itself the most basic thing of all. “It’s really not that deep,” Brown wrote. And yet! Can we really deny that in the decontextualized, dehistoricized desert of social media, words lose their original shape and take on new ones? As a word is passed around this landscape, back and forth across the Internet, it seems worth considering the relationship between the different meanings it accrues.

In my experience, calling someone “thirsty” either in public or behind their back seems to happen most often when a man says something inappropriate to a woman on the Internet. “To be ‘thirsty’ is to be needy of someone’s attention without realizing it,” my friend Kevin told me. “It’s not necessarily romantic attention, but when it is, ‘thirsty’ is really just a euphemism for being horny and lacking any self-awareness about it.” Kevin says he isn’t thirsty, but knows it when he sees it.

The idea of “thirst” seems to me not altogether unrelated to certain put-downs of my youth: God help you if people thought you were a “poser,” for example, or a “follower,” or a “try-hard.” There were nuances, even then, that differentiated the meaning and use of these words, but what unified them all is that the connotation of desperation to be acknowledged, included, and validated. In a word: to be cool. Even now, the artifacts of cool may change, but the artifice remains, and what will always be the least cool of all will be to be caught in the construction of the artifice. What sets “thirst” apart from these earlier ideas, however, is that while the “poser” was just wearing cargo shorts because everyone else was wearing cargo shorts — and even the most precocious sixth grader can hardly be expected to develop a coherent and thoughtful personal style — a grown adult who is “thirsty” is someone who ought to know better, but doesn’t. It is a personal failing of another order entirely.

“I think ‘thirst’ is generally pretty gendered. And for those of us (women) that deal with casual harassment on a daily basis, it’s less of a cute concept to embrace,” my friend Nicole told me over Gchat. Kevin speculated that “pointing out a man’s ‘thirst’ is a gentler way of telling him that he is acting inappropriately.” My friend Jessie told me, “Women are very sensitive to thirst. If a woman calls you thirsty, you are being thirsty.” For this reason, the epithet can be quite scalding when used sincerely. “I would not call someone thirsty if they were not being thirsty,” wrote Casey, another friend. “I’ve called you thirsty in a joking way and you got mad.” It’s true, I did.

What is the relationship, then, between thirsty men harassing women on Twitter — or anywhere, really, but especially on Twitter — and thirsty brands harassing consumers, as mentioned in that New York Times piece? Most Twitter users are probably familiar with the experience of mentioning a product on Twitter only to have the Twitter account belonging to that product’s producer butt into the conversation. It might be useful for a certain kind of man to remember that feeling he gets — some combination of annoyance, surprise, and disgust — when an uninvited brand interrupts a conversation or canoe. Is it possible, he might ask himself, that I — not a brand, but a man — have behaved in such a way to provoke similar feelings in the people to whose conversation I felt compelled to contribute? Maybe. Maybe not! Social cues can be hard to read, especially on the Internet. We’ve all been there.

“Thirst is different than hunger,” another friend wrote. (The body, it turns out, is a rich source of figurative language.) “Hunger is a long-term desire for something that is definitely personal but doesn’t require another person to be on the other end of it.” My friend Caroline reassured me, “It’s always good to be excited or eager about something. Being passionate shouldn’t mean you’re desperate, but sometimes wires get crossed. I think holding in thirst to please other people and to be ‘cool’ is the thirstiest thing one can do.”

I wondered about this. Is it thirsty to contact editors, asking to meet for coffee? Is it thirsty to fave their tweets? By definition, if I were thirsty — in this way, or otherwise — I wouldn’t even know it. More to the point: is it thirsty to ask friends and acquaintances for quotes… for an article about “thirst?” Is this whole piece thirsty?? Maybe! “If a person is being thirsty in order to further his or her career (e.g. an email to friends asking for quotes about what it means to be thirsty), it’s rude to call that person ‘thirsty’ to his/her face,” my friend Abe wrote. “Which is what I did, and I feel bad for it now.” (“This email has created a metatextual irony loop so powerful it rivals the Large Hadron Collider,” he also wrote.)

| ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄ ̄  ̄ ̄  ̄ ̄ ̄| | i’m so fucking | thirsty | |________ _ __| (__/) || (•ㅅ•) || / づ”

— Sin Subadere (@hadakasinpie) July 7, 2014

Again, this feels like the most basic definition of the word used as slang. But slang, almost by definition, is where language is at its most fluid and dynamic — on the periphery, outside of codified, official meaning. Indeed this is its cachet, and it plays a large part in why so many kids spend so much time studiously adopting — appropriating — mannerisms and phrasing that originate from well outside their immediate surroundings. And it is why the re-appropriation of certain words, in turn, is such a radical rhetorical strategy. Indeed, it seems to me that this is what is happening with the idea of the “thirst trap” — shorthand, in its way, for a woman (or Idris Elba) owning her (or his) sexuality and deploying it when, where, and how she sees fit.

All of which is to say: every once in a while, people seem to stumble into a word that can be used to describe a kind of experience that they were less able to describe before — and that, perhaps, is not such a bad thing.

I’ve heard it recommended that one drink at least half as many ounces of water in a day as one weighs in pounds. I’m not sure of the scientific authority behind this benchmark, but I tend follow it anyway. I’ve also heard that you’re not supposed to give someone who is literally dying of thirst too much water at once, because it will literally make their cells explode. Maybe that’s an Uber Fact. Anyway! It behooves me to drink — by the mysterious metric mentioned above — at least 85 ounces or so of water every day. (I hover around 173 lbs.) I hit this goal regularly, filling and emptying my 32-ounce Nalgene water bottle at least three times a day. The initial act of filling my water bottle requires thought, and action, but the drinking of the water has become an almost thoughtless action. I also drink a lot of coffee. What I’m saying is that I pee a lot. It’s fine. But also: you don’t have to be thirsty to drink. And in fact, if you drink enough water, you needn’t ever be thirsty in the first place.

Brendan O’Connor is a reporter who lives off of the L train.

E.R., "Feluha"

Endeguena Mulu, aka E.R., is one of a handful of musicians who make up the Ethiopiyawi Electronic movement, which lives mostly on a circuit between Addis Ababa and Washington DC. The song is a surreal and dizzying genre mash, with scurrying masenqo strings sliding under rich electronica shot through with cane flutes. (See previously: Mikael Seifu.)

Franchise Unbeatable

“At the end of the day, Brand Ebola may be too strong to counter. ‘It’s got high awareness, it’s easy to understand, it’s got a fairy simple story,’ said Calkins. ‘It’s the ice bucket challenge, but bad.’”

The Internet's Invisible Sin-Eaters

by Adrian Chen

In this month’s Wired, Adrian Chen visits the Philippines to speak with professional content moderators — the people who scrub all the dick pics and beheadings from the world’s biggest sites before they reach users’ eyes. It’s job that, he says, “might very well comprise as much as half the total workforce for social media sites.” Sarah Roberts, a media studies scholar at the University of Western Ontario focusing on commercial content moderation, is quoted in the piece. They caught up over chat.

AC: One thing I would have liked to include in my piece was how you got interested in studying content moderation.

SR: Well, it’s a pretty simple story. I was perusing the NYT one day and there was a very small story in the Tech section about workers in rural Iowa who were doing this content screening job. They were doing it for low wages, essentially as contractors in a call center in a place that, a couple generations ago, was populated by family farms. I call it “Farm Aid Country.” I say this as a born and raised Wisconsinite, from right next door.

So this was a pretty small piece, but it really hit me. The workers at this call center, and others like it, were looking at very troubling user-generated content (UGC) day in and day out. It was taking a toll on them psychologically, in some cases. I should say that I’ve been online for a long time (over twenty years) and, at the time I read this, was working on my Ph.D. in digital information studies. I was surrounded at all times by really smart internet geeks and scholars. So I started asking my peers and professors, “Hey, have you ever heard of this practice?” To my surprise, no one — no one-had.

This was in the summer of 2010. Right there, I knew that it wasn’t simple coincidence that no one had heard of it. It was clear to me that this was a very unglamorous and unpleasant aspect of the social media industries and no one involved was likely in a rush to discuss it. As I interrogated my colleagues, I realized that many of them, once they were given over to think about it at all, immediately assumed that moderation tasks of UGC must be automated. In other words, “Don’t computers/machines/robots do that?”

Right. I actually thought that at least some of it would be done like that before doing this story. That was one of the most surprising things, how little is actually automated.

So that got me wondering about our propensity to collectively believe (I’d say it’s more aspirational, actually — wishful thinking) that unpleasant work tasks are done by machines when so many of them are done by humans. As I’m sure you learned, and I did, too, content moderation of video and images is computationally very difficult. It’s an extremely sophisticated series of judgments that are called upon to make content decisions.

“A list of categories, scrawled on a whiteboard, reminds the workers of what they’re hunting for: pornography, gore, minors, sexual solicitation, sexual body parts/images, racism. When Baybayan sees a potential violation, he drills in on it to confirm, then sends it away — erasing it from the user’s account and the service altogether — and moves back to the grid. Within 25 minutes, Baybayan has eliminated an impressive variety of dick pics, thong shots, exotic objects inserted into bodies, hateful taunts, and requests for oral sex.

More difficult is a post that features a stock image of a man’s chiseled torso, overlaid with the text ‘I want to have a gay experience, M18 here.’ Is this the confession of a hidden desire (allowed) or a hookup request (forbidden)? Baybayan — who, like most employees of TaskUs, has a college degree — spoke thoughtfully about how to judge this distinction.”

It’s interesting that this still seems so undiscovered because content moderation has been going on since the beginning of the commercial internet, really.

It certainly has. Of course, a lot of early moderation was organized as volunteer labor-people doing it for fun, for status or prestige or for perks. (Think people who like to edit Wikipedia nowadays.)

Right, AOL used to run completely on volunteer moderators.

That’s right. [More here.]

Then they had that scandal where the mods sued for payment, right?

That’s right, too! Hector Postigo has a piece on this that I cite in my own work. As the internet went from a niche and rarified space filled with people mostly accessing from universities, R&D facilities, and the like, to a graphical and commercial medium, the need to be more tightly control content immediately grew.

I can’t help thinking of the development of commercial content moderation as a sort of loss of innocence, like going from idyllic farm communities where everyone looked after each other to this industrial hellhole where people work in factories as fast as possible.

Whereas, when I started hanging out online, I was accessing systems that were, quite literally, in somebody’s closet in an apartment in Iowa City. I think there’s a real tendency to look at it that way. I certainly deal with a certain level of nostalgia for “the way it was” before the World Wide Web took off in a big way, around 1994.

That having been said, I think that kind of hindsight is a little anachronistic. For example, consider Usenet. This was a place/site/medium that was self-governed, for the most part, broken down by each newsgroup’s own norms, interests and users. Back in these pre-Web days, an errant click in there could take you to content you might never, ever be able to unsee. Trust me-it happened to me. And so the CCM workers I’ve talked to in my own research have been quick to point this fact out. They’ve told me things like, “Look-you wouldn’t want an internet without us. In fact, you wouldn’t be able to handle it.”

I don’t know if you had this experience with the Manila-based folks, but the people I talked to in Silicon Valley and scattered elsewhere in North America had a real sense of altruism about the work they did. One of my participants told me she used to refer to herself, in her CCM days, as a “sin-eater.” She’d eat other people’s spew, garbage, verbal vomit, racist invective — their sins, in other words. So that other people wouldn’t have to.

I think to some extent all of this craziness around internet harassment has been the bubble bursting on a long illusion that the problem of nastiness on the internet had been sort of solved by Facebook.

So much of hand-wringing online (and let me say that I do not condone online bullying or harassment in any way-witness this nightmare called #gamergate as the latest in many gross examples) is focused on the consumers of the content. In the mid-90s, it was very much a “think of the children!” kind of thing. But, my God, if just being exposed, as a viewer/recipient/consumer to such content can be so profoundly damaging, what happens when you are embedded in that cycle of production, like CCM workers are?

Right.

And let’s talk, for a moment, about the labor organization situation for CCM workers, and how that plays into their invisibility. The kind of labor organization that we tend to see, and you can corroborate or speak to what you’ve seen that might differ, among people who participate in this practice, is almost always not a full-time, full-benefits, full-status kind of job

Instead, people are often contractors, limited term, hourly/no benefits, or some other kind of arrangement that is decidedly “less than”-all the way down to digital piecework kinds of arrangements.

Well, in the Philippines it is actually full time, with benefits, at least if you’re working for one of the big outsourcing firms. I was actually surprised at how little content moderation is done through crowdsourcing. I talked to an exec at CrowdFlower. They had a photo moderation tool but they ended up shutting it down because it wasn’t effective enough. And there was another app that was supposed to allow you to do photo moderation on your smartphone, but they didn’t even launch before pivoting to some other kind of crowdsourcing. It seems like you need a certain amount of training and sustained labor to make it work.

“’I get really affected by bestiality with children,” she says. ‘I have to stop. I have to stop for a moment and loosen up, maybe go to Starbucks and have a coffee.’ She laughs at the absurd juxtaposition of a horrific sex crime and an overpriced latte.

Constant exposure to videos like this has turned some of Maria’s coworkers intensely paranoid. Every day they see proof of the infinite variety of human depravity. They begin to suspect the worst of people they meet in real life, wondering what secrets their hard drives might hold. Two of Maria’s female coworkers have become so suspicious that they no longer leave their children with babysitters. They sometimes miss work because they can’t find someone they trust to take care of their kids.

Maria is especially haunted by one video that came across her queue soon after she started the job. ‘There’s this lady,’ she says, dropping her voice. ‘Probably in the age of 15 to 18, I don’t know. She looks like a minor. There’s this bald guy putting his head to the lady’s vagina. The lady is blindfolded, handcuffed, screaming and crying.’”

.

In your disseration you talked to some guy who lives in Mexico and seems to be doing pretty well content moderating.

Yes, he was a principal in that company, a boutique firm, and he came into that situation in a position of wealth from a previous career. So, in essence, he was management, not one of the lay CCM workers. He appreciated the flexibility of his worklife. And some of the workers I’ve talked to who have the ability to work in that way do like it. but the other CCMers I talked to worked in a major Silicon Valley tech firm and they were on-site there, even though they were contractors (i.e., not full-time, full-status employees of the company).

So where are things headed in the future? It seems to me that moderation work, or at least a similar kind of assembly line content processing, is only growing. When I was in the Philippines I saw one outsourcing firm where dozens of workers were transcribing 19th-century census records for a geneaology firm.

One interesting trend I’ve seen is to treat CCM like a feature, and to suggest, as Whisper has done, and I’ve seen in some job postings, that CCM is more of a curatorial or selection practice. In this way, platforms or sites advertise that they have moderators selecting only the very best content (“best” being a mutable sort of term that could mean: most relevant, most accurate, most interesting, etc.) for the users of that platform or site. While I don’t necessarily think this will actually lead to immediate improvements in the work lives of CCM workers, at the least that kind of up-front acknowledgement that CCM practices are happening on a site and that those workers are performing service at least lifts the curtain on workers who typically remain hidden. But much is to be done on this front, and I think for long-term improvements and solutions it will require a collective effort among workers, activists and academics (and journalists, too). This is why I’m so looking forward to the Digital Labor (#dl14) Conference happening at the New School next month. It will be a great place for these conversations to start/continue/take shape.

Adrian Chen is a freelance writer in New York. He is the leader of Gamergate.

New York City, October 26, 2014

★★★ The wind outside sounded like cars whooshing by, heard from the shoulder of the highway. Enough clouds moved in through the morning that the soap bubbles being blown at the community block fair failed to shimmer. Pedestrians were ambushed by a yellow vortex of honeylocust leaves, swirling a full story high, making them flinch and buckle. Sun took over for the three-year-old’s naptime, then went away by the time he was awake for the block fair again. A five-piece jazz band played outside the bank, and a man in a checked cap danced quietly and extravagantly off to the side. Leftover balloons, black and orange, were being distributed to children and to the sky. “How come there’s a huge wind?” the three-year-old asked, as he made the turn onto 70th into gusts. A portable boiler room trailer hummed by the curb, feeding thick hoses into an apartment building. The boy insisted on shedding his jacket as soon as he entered the playground, while parents or guardians thrust their hands into their pockets. The darkness lay heavily at four in the afternoon; there were still occasional thin patches of blue, but small ones and always somewhere else. The sun got under the clouds downriver at last and sent a coppery glare to flood the southern faces of the buildings. Magenta ruffles spread across the sky. By shortly after six, it was all over.

Eat Bread

Gluten sounds totally disgusting. It is not so far off from, like, “moisten” or “ooze” or “smegma.” So it is no surprise that it chafes, no matter whether you think it does terrible things to your insides (despite not having been diagnosed with celiac disease) or you think that anyone who has a self-assessed gluten problem is a terrible asshole in direct to proportion to how loudly that person proclaims their gluten sensitivity (despite not having been diagnosed with celiac disease).

In this week’s New Yorker, Michael Specter does not attempt to resolve this country’s ongoing gluten crisis so much as survey its hazardous, craggy territory, but the vague evidence that has amassed into nearly corporeal little piles about the relationship between humans and the protein found in the cereal grain that supplies twenty percent of the world’s calories points in a few, complicated directions:

1) The rate of celiac disease — in which gluten triggers a definite immune reaction — is definitely going up, for totally mysterious, probably environmental reasons

2) There is some interesting (and HIGHLY PRELIMINARY) evidence that what some people who suffer from some form of genuine chronic gastrointestinal distress — and who think that eliminating gluten eases their symptoms — are actually having issues with is a bundle of complex carbohydrates called FODMAPs, which are found in foods ranging from apples to milk to garlic (meaning it’s extremely difficult to cut out of your life with a slogan: “I can’t eat foods FODMAPs, it causes gastrointestinal distress” doesn’t sound as tidy “I don’t eat GLUTEN, which is in carbs, because it’s poisoning our brain”)

3) Most of the one-third of adults self-diagnosing that they — and especially, their children — have some form of what has come to be known as non-celiac gluten sensitivity are charlatans and should be stoned, by which I mean fed into a stone mill used to grind wheat into flour

4) Even though industrial bakers have been adding increasing amounts of gluten to dough in order to make it heartier, and this might make it a little bit true that all this gluten is causing some amount of mild discomfort in some people, maybe (because the amount of gluten in wheat itself has definitely not changed over the course of the last hundred years, despite what the anti-GMO latchers-on would like to say about it) but, by the way, most of the gluten-free products are filled with garbage to make up for the lack of gluten, so they might give you diabetes eventually

5) Michael Specter once added this extra gluten, in the form of vital wheat, to his home-baked bread, but does not any longer

So, unless you have celiac disease, eat the heirloom wheat bread with a healthy pat of butter from a grass-fed cow. Unless, of course, you have a dairy allergy, which is definitely a real and true thing.

Mister Lies, "High (ft. Harrison Lipton)"

Does this sound a little bit like Massive Attack? It would be well within the regulations of tribute and nostalgia: “Teardrop” came out in 1998. The rest of the album, which is slow and lush and worth a listen, brings to mind The Notwist’s Neon Golden, which came out just four years later. Music, the loop, is now barely ten years in circumference.

Toward a Resolution of the Moral Quandary of Eating on the Subway

by Matthew J.X. Malady

People drop things on the Internet and run all the time. So we have to ask. In this edition, writer and Ridgewood resident Brendan O’Connor tells us more about two guys having dinner — at the dinner table — on the subway.

Well that’s something you don’t see every day pic.twitter.com/Lr9oVq6pvm

— Brendan O’Connor (@_grendan) October 15, 2014

Brendan! So what happened here?

OK! So. I was taking the M train from Brooklyn to Manhattan. Despite its problematic schedule, the M train is my favorite because in Brooklyn and Queens it runs above ground. I am young enough in the game for this to still be magical because you can look outside. Also you can tweet.

The train was pretty empty when these guys got on. At first, I wasn’t sure that they were going to open up the table. It was a folding table. But they did. Then they ate McDonald’s on it. I could smell the McDonald’s; it smelled good. I don’t know that anyone was particularly bothered by what was going on. Maybe by the smell though? Sometimes the smell of McDonald’s can be sort of overwhelming. The sense I got from the few other passengers was one of bemusement rather than annoyance, though.

As you can see, the two gentlemen are wearing ties and lanyards. Ties and lanyards? Tell us more! Ha ha ha. No but seriously, if I recall correctly they got on the train at Flushing Avenue, which is near Woodhull hospital. A hospital is a place where people sometimes wear ties and lanyards? So maybe that’s where they were coming from? Idk. There’s also a McDonald’s around there. Then again, maybe they didn’t get on the train at Flushing. Maybe I’m constructing that memory to support my equally tenuous hospital theory. Let’s look at the facts: I got on the train at Myrtle-Wyckoff; they got on after me; they got off at Marcy Avenue — the last stop before Manhattan. That’s what we know. This will be relevant later.

I have to know: What did these two dudes talk about at their subway dining table? Did they reference the ridiculousness of what they were doing or joke about it or anything like that? Or no?

The dude on the left was talking about how the table was nice to have for his longer train trips. He mentioned having to be on the train for almost an hour sometimes — dunno if that’s his commute, or what. He was saying that it was nice to have the table, then. Or maybe he was saying it *would* be nice to have the table, then? It was unclear. The table quite clearly belonged to the man on the left, though, and it was clearly not his first time using the table on the subway.

But they weren’t on the train for an hour. Like I said before, they got on after Myrtle-Wyckoff and got off at Marcy Avenue. So they were on the train for…ten minutes? Maybe? Ten minutes at most, if the train was running really slow. This is good journalism right here. The point is that the man on the left was much more comfortable setting up a table — his table — on the subway than the man on the right. The man on the right was clearly out of his element.

Anyway, they didn’t really talk about the table. They talked about Iggy Azalea. The man on the left had a theory that she looks like Marlon Wayans in the movie White Girls. (Look, I didn’t say it.) They laughed about her beef with Snoop Dogg. Or Snoop Lion, rather. Maybe they just referred to him as Snoop. I’m not sure.

Lesson learned (if any)?

Men are bad? Lol idk. It’s certainly another entry for men taking up 2 much space on the train dot tumblr dot com. Although perhaps not, because like I said, the train was pretty empty. How much space is 2 much space? Probably nobody ever needs to open up a folding table on the subway. But, like, if you have it, and there’s nobody around… Look I’m just saying, I might have done the same thing, if I had McDonald’s and a table upon which to eat it.

As it happens, this is not the first man with furniture I’ve seen on the subway:

A photo posted by Brendan O’Connor (@boc9000) on Jul 7, 2014 at 4:37pm PDT

Just one more thing.

I miss pretending to ignore the Showtime kids.

Join the Tell Us More Street Team today! Have you spotted a tweet or some other web thing that you think would make for a perfect Tell Us More column? Get in touch through the Tell Us More tip line.

Matthew J.X. Malady is a writer and editor who was in New York but is now in Berkeley.