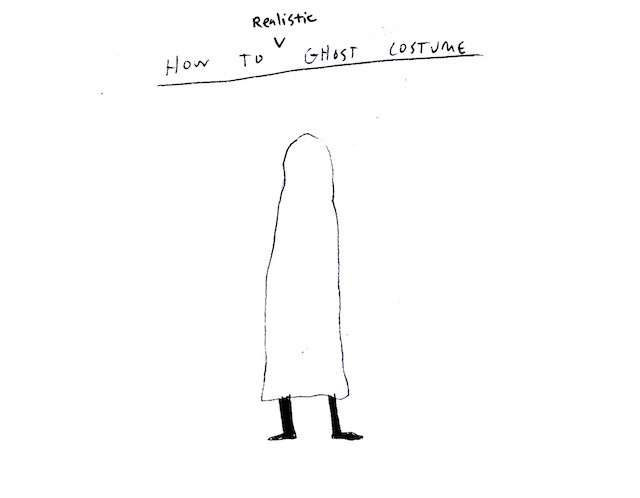

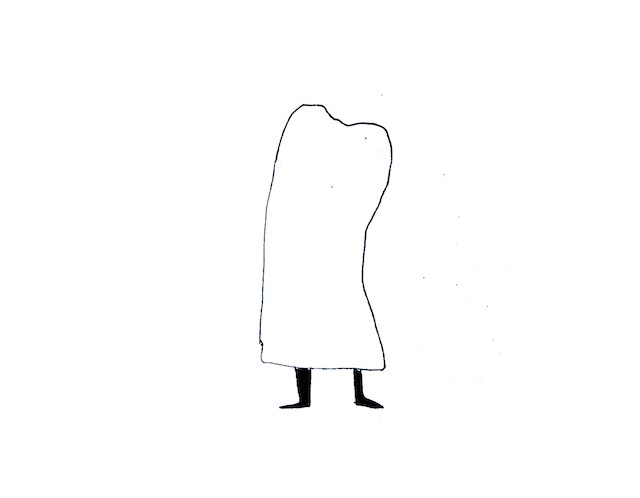

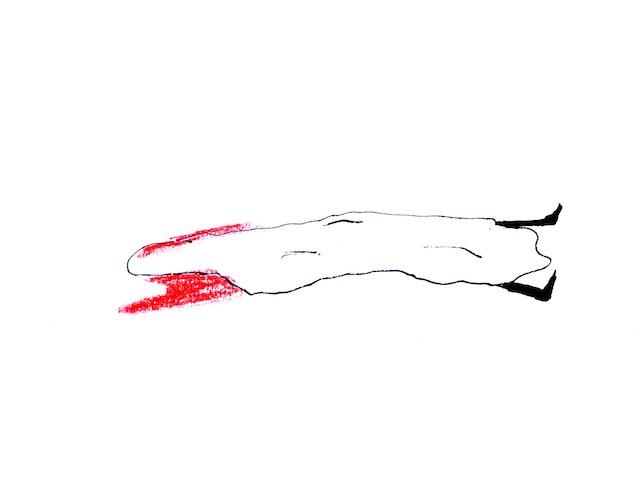

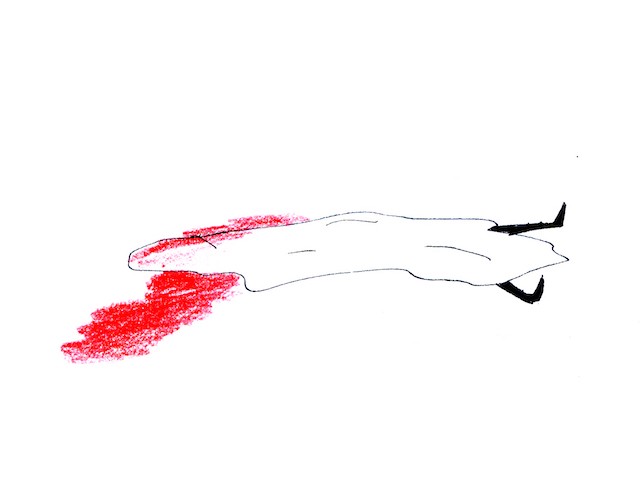

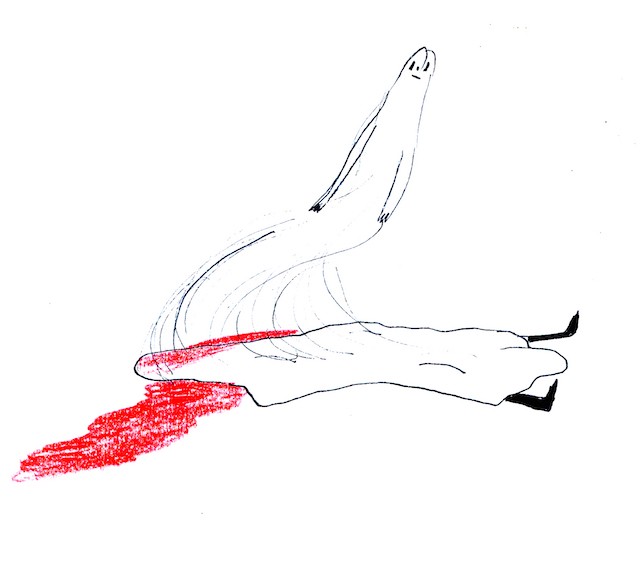

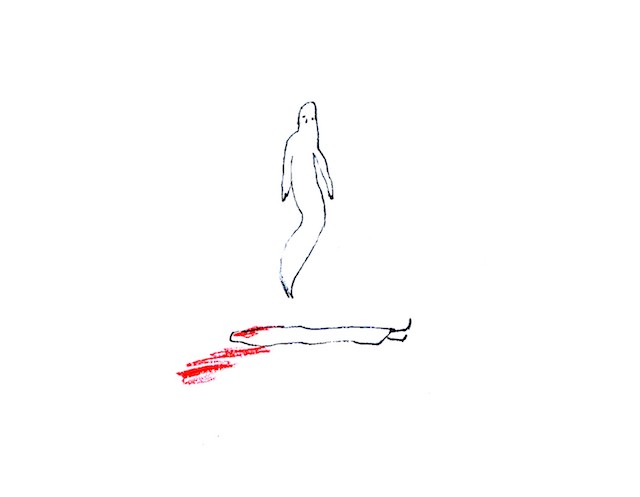

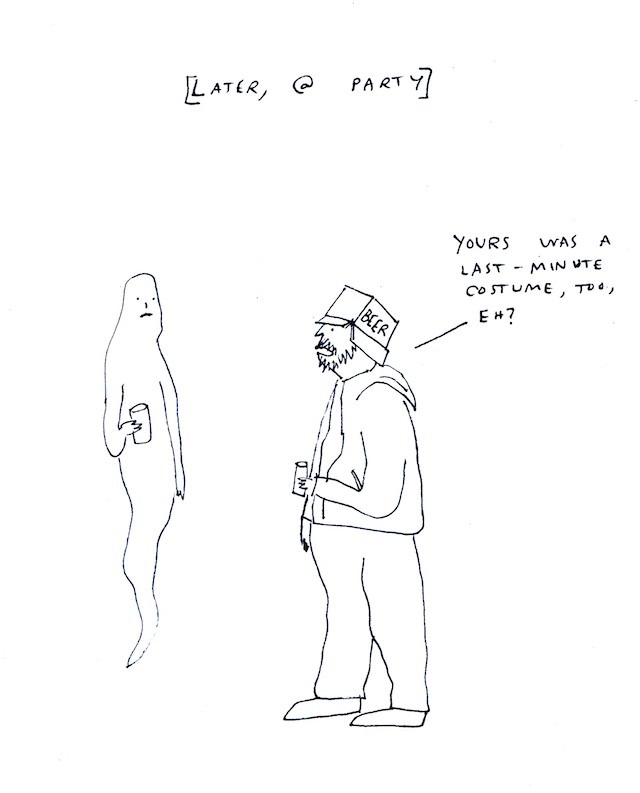

How to Make a Spooky Last-Minute Ghost Costume

by Hallie Bateman

Hallie Bateman is a freelance illustrator and cartoonist based in Brooklyn. She is on Twitter and Instagram. She doesn’t want your attention but she needs it.

Eat Spinach, Not Kale

Recently, the general public, especially younger people in the cities, have begun to embrace strong flavors previously thought of as icky, like bitterness, fermentation, funk, fat and umami, which are now all prized flavors. This is good. But Americans, as always, are unable to do anything in moderation, and, hypnotized by the constant racket of food television, food blogs, restaurant blogs, and have-you-tried-this, insist that if strong flavors can be good, then even stronger flavors must be better. This is why we can’t have a hoppy IPA; we have to have the hoppiest quadruple-IPA science can concoct. We can’t have a normal bowl of chili; we have to bump up the savory flavor with umami-heavy ingredients like marmite, soy sauce, and anchovies, and who cares if those flavors work together? And we can’t use spinach anymore, because there are greens that are stronger and more bitter, and thus better, like kale. Eating spinach is something your parents would do. Eating kale — stringy, bitter, aggressive kale — is the mark of an adventurous, flavor-forward connoisseur.

Kale is a perfectly fine ingredient, but its bitterness and toughness have become indicators of quality to a certain segment of Americans, rather than characteristics to be overcome through cooking. And that’s led to its usage as a trendy ingredient in weird new places. But: Dishes do not usually become better or even more interesting when a trendy ingredient or process is foisted onto them. They almost always become worse. For example: the classic spinach, bacon, and egg salad, familiar to anyone who’s ever been to a steakhouse. This is a classic for a reason. The flavors and textures work beautifully, each individual ingredient holding its own. Replace the spinach with kale, and everything’s thrown off. Typically, the hot vinaigrette slightly wilts the spinach, adding a new flavor and texture, but kale is much tougher and won’t even notice that a hot vinaigrette has been added. Kale’s raw flavor, unchanged by the dressing, will thus overwhelm the egg and bacon.

That’s not to say that kale is a bad ingredient; it just needs to be used thoughtfully. Kale is in the brassica family, like collards, so it’s related to cabbage, broccoli, and brussels sprouts. It’s not related to spinach, which is in the beet family. The greens in the beet family, which also include chard, are more delicate and tender than the brassica greens; they cook much more quickly and can be eaten raw, without the rigamarole of massage (and I’d argue that no matter how thorough the massage, raw kale never attains an appropriately tender texture). The stems of beet-family greens are also edible and delicious, even the tougher chard stems (which take well to roasting and pickling).

Spinach comes in a few different forms. Probably the most common on grocery store shelves is bagged baby spinach. Never buy this. (Never buy any bagged green, now that I think about it. They go bad within a day of being opened, and are typically several times more expensive than the non-bagged kind.) If you can get real spinach from the farmers market, the kind with the little pink caps on the roots still attached, do that, but totally usable tasty spinach is also available year-round in grocery stores. It should come in a bundle, and in probably two types: one is very dark green and has curled edges around the leaves; this is called savoy spinach. The other is slightly lighter and has flat leaves, like a larger version of baby spinach. I tend to prefer savoy if I’m cooking it for awhile, and flat-leaf if I’m eating it raw, or doing a real quick cook.

In the fall and winter, I pretty much stick wholly to cooking with greens; they become hearty and filling and satisfying, just what you want in cold weather. Let’s start the recipe section off with a pretty simple lentil soup with spinach.

To start, saute a chopped onion and about five cloves of garlic in olive oil in a heavy soup pot or dutch oven. While that’s softening, take one bunch of flat-leaf spinach and chop it. I like to keep the stems all tied up the way it came at the grocery store and then just chop the leaves into slices about half an inch wide. Chopping spinach is key for wilting, which is what we’ll be doing here; you don’t want a huge drippy slimy leaf of spinach, you want it to break down into almost a sauce. Throw them in a colander, wash, and either spin dry or let sit.

When the onion is translucent, throw in maybe a spoonful of ground coriander. Stir the onions around to fry the coriander; a bunch of stuff will stick to the pan, which is fine. Add a cup of split red lentils (do NOT substitute any other kind of lentils, the recipe will not work) and about three cups of water or chicken stock or vegetable stock. Bring to a boil, then lower the heat and cover it. Cook for about forty-five minutes, stirring every five or ten minutes, until the lentils have broken down and no longer look like lentils. When done, season heavily with salt and pepper, then put in your entire bunch of spinach. This will look like too much spinach! It is not too much spinach. Add maybe a handful at a time, stirring until it wilts enough to add in the next handful. When done, squeeze about half a lemon’s worth of lemon juice into the soup. Serve with pita.

I also love spinach tacos! These are totally non-traditional, but who cares. First, you’ll have to make your pickles. Either with a mandoline (best option) or a knife, slice one whole red onion into paper thin slices. Scatter them in a glass storage container. In a saucepot, bring a cup of apple cider vinegar and a quarter cup of sugar to a boil, and when it boils, pour it over the onion and loosely cover. Let it sit out and cool while you do the rest of your work.

In a dutch oven, saute a sliced (not diced) onion and a few cloves of garlic in olive oil until translucent, then dash in a bit of cumin and dried chile powder (or flakes) and stir to fry and coat. When fragrant, add in a whole bunch of spinach, sliced and washed exactly the way you did it for the lentil soup, but you can use the savoy variety for this one. Mix that all up until it starts to wilt, then pour in about a quarter cup of beer (I usually use some kind of mild pale beer like Presidente). Stir hard with a spatula to deglaze all the good stuff on the bottom, then cover and lower heat and cook until the spinach is done but not mush — about five to ten minutes, or however long it takes you to finish the rest of the beer you opened. Then season with salt to taste.

To serve: throw some corn tortillas on a hot dry cast iron pan to brown, then place a glob of spinach on the tortilla, followed by some queso fresco (or feta), some chopped cilantro, a few pickled onions, a squeeze of lime, and some hot sauce of your choosing. (JK, you don’t get to choose. Use Tapatio.)

Finally, let’s move to the north of India for saag paneer. Chop and wash spinach as before. If you have a mortar and pestle, throw in a few cloves of garlic, one chile (serrano or chile de arbol or Thai birds-eye would be good), and about a thumb’s worth of peeled and loosely chopped ginger, and smash thoroughly into a paste. (If you don’t have a mortar and pestle, toss everything in the food processor until it’s a paste.) In a heavy-bottomed pan, add some vegetable oil and then this paste, frying to add a little color, then add about a teaspoon of garam masala mix. Toast that until fragrant, then add in the spinach and cook until soft, maybe five or ten minutes. From here you can do a few things: you can add coconut milk or cream to make it richer (I usually don’t), and you can either puree this in the food processor or not (I usually do; I like a very smooth saag).

If you want to make your own paneer, it’s easier than you’d think; you basically just curdle milk with lemon juice and then press the curds together. (This is a good basic recipe.) Saag paneer also works well with tofu, which is basically just paneer but made with soymilk instead of cow milk. Sear your paneer or tofu in oil, then mix with the saag. Serve over rice.

Spinach may not be cool, but I hope it stays that way, because it costs about two bucks for a huge bundle and it’s delicious, healthful, and tremendously flexible and easy to work with — easier, by a long shot, than kale. A good cook will think about ingredients and methods, what those ingredients are best at and what they’re not so good at, and use them accordingly, rather than blindly following food trends to their illogical extreme. And a good cook will also use spinach. Because spinach is so tasty.

Crop Chef is a column about the correct ways to prepare and consume plant matter, by Dan Nosowitz, a freelance human who enjoys hot salads and lives in Brooklyn, naturally.

Photo by David Wagoner

The Super-Urban Promise

“Imagine the ability to create a standing order of Starbucks delivered hot to your desk daily,” commands CEO Howard Schultz. “That’s our version of e-commerce on steroids.” IMAGINE. At face value, this sounds like a reductio ad absurdum scenario for the new logistics-obsessed economy, in which a product is created and then shipped to people who could either make it on their own or purchase it in person at one of the many physical retail locations situated between their beds and their desks. But no, if you actually do imagine this, it’s absurd but appealing: If you could summon coffee to your desk every day for a nominal fee, with some sort of set-it-and-forget-it ordering system, you might consider it. After the first week you would stop thinking of it as crazy, and it would just be there, an ambient feature of the economy like bottled water or $0.99 hamburgers.

A system like this would only work in a limited set of places and in a limited set of scenarios. It is, like so many new delivery services — Seamless, Freshdirect, Caviar, SpoonRocket (sorry), Washio (seriously just one more), DoorDash — a concept for cities, where physical density means delivering a low-priced order is economically feasible.

But if you unspool this, supposing that nothing interferes with the god-given inevitability of every delivery startup and the manifest destiny of the overall on-demand economy, you end up with some pretty big adjustments to the definitions of urban and suburban lifestyles.

The new view: To live in a city with disposable income is to be able to have everything delivered, expensive or inexpensive, disposable or edible or whatever, directly to your door. To live outside of the city is to leave that grid to settle for an older, lesser grid, in which cheaper products don’t come to you but the other way around. You can still get more expensive things delivered, or cheaper things delivered for a fee, or just Amazon things, but probably not coffee or one bowl of soup or laundry. Stopping by the coffee shop, in this future optimum urban utopia, is either an economic necessity or an affectation, either downscale or premium, like thrift shopping vs. vintage shopping. Environmental identities get muddled and flipped; previously important differences between affluent urban, suburban and rural lifestyles fade into the background. Cities, no longer the difficult but rewarding lifestyle alternative, become the easy option.

Photo by Niels Linneberg

Entropy Negative

“Slipknot are no longer in step with the times either, but here they are selling six figures anyway hawking the same downtuned riffs and frustrated aggression as ever. At the peak of the band’s popularity, with the likes of Spears and Eminem routinely moving a million copies in a week, 132,000 in sales wouldn’t have come close to topping the chart. But on the flattened playing field that is 2014, it all but guarantees a #1 debut. At a time when many legacy acts can barely muster 50,000 on their first week, Slipknot’s numbers are undoubtedly impressive. Still, The Gray Chapter’s strong showing doesn’t herald a big comeback for nu-metal as much as it affirms that nu-metal has become the province of an aging demographic.”

New York City, October 29, 2014

★ Chilly but sticky, a morning at odds with the season and itself. The clouds were everywhere, but thin enough that a contrail showed whiter through or against them. The sun cast fractional-strength shadows. Mid-afternoon was more tolerable, out on the fire escape, under sun further diminished. Then the daylight died entirely, and by the commute home, the cold was unambivalent and a thin rain was falling — so thin it seemed watery, despite already being water.

Fantasy Delineated

“Let’s ponder, for a moment, the kind of culture an ambulatory fungus might construct. Individual fruiting bodies would probably seem, to us, utterly unconcerned with their own survival when confronted with large-scale dispersive destruction. Struck with a fireball, or blown up by your own bomb? No problem! The force of the blast spreads your spores over the battlefield. Chopped up by a surgeon to patch up some other creature (not necessarily a goblin)? Great! The new creature will carry you around for the rest of its life, dispersing your spores on the way. Killed in battle? Your spore-laden blood sticks to your adversary’s boots — and when she washes off in the nearest river, the current will carry your spores to unknown lands. Eaten by a dragon? Best of all possible worlds.”

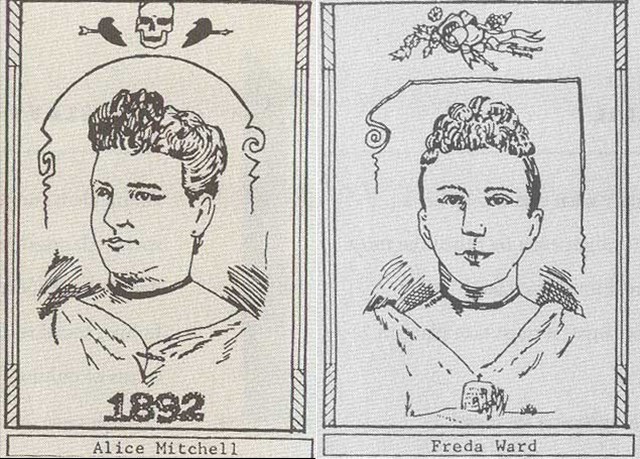

Erotomania and Murder in Memphis

Alice+Freda Forever: A Murder in Memphis by Alexis Coe, is out now. You can order it from wherever you choose to prepare for the coming apocalypse:

• Powell’s

• Amazon

Less than an hour after the murder, Memphis’s Chief of Police knocked on the front door of the Mitchell’s fashionable home on Union Street. Chief Davis was sorry to disturb “Uncle George,” as the retired salesman was affectionately called, and sorrier still for the decidedly unpleasant nature of the call. He had come to arrest George Mitchell’s youngest daughter for the murder of Freda Ward.

George had been expecting him. He readied himself and Alice for a trip to the jailhouse, just a few minute’s walk from the scene of the crime. He waited patiently as Davis booked his nineteen-year-old daughter on the charge of murder, amiably chatting with jailers, all sympathetic friends who promised to look after Alice while he sought legal representation.

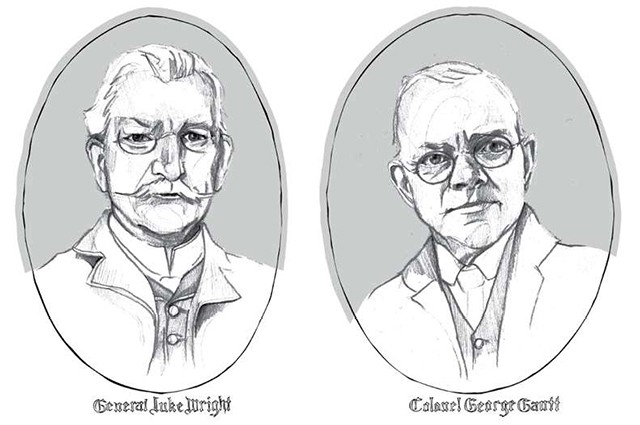

By eight o’clock that evening, George returned with two of the most prominent, expensive attorneys in Eastern Tennessee, if not the entire state. Both Colonel George Gantt and General Luke Wright were affluent, respectable Memphians from old, Southern families. They had emerged as community leaders after a series of yellow fever outbreaks in the 1870s all but ruined the city; Memphis’s charter was revoked, the economy stalled, and its population dwindled, with thousands buried and many more having fled, never to return.

Col. Gantt was considered Memphis’s preeminent litigator, peerless in legal research and unrivaled in courtroom debate. The firm that bore his name was a breeding ground for high level political and business leaders, whose power and wealth gave them an extraordinary degree of influence in the South.

Gen. Wright, son of a Tennessee Supreme Court Justice, had a distinct advantage in the case. His title was honorific, bestowed upon him for a commendable job as attorney general in Shelby County, where the Mitchell-Ward case would be heard. He would go on to collect far more titles in his career, serving as the first United States Ambassador to Japan, and then as Secretary of War under President Theodore Roosevelt.

Despite the defense’s legal prowess, it was George Mitchell, and not the lawyers he hired, who determined Alice’s plea. It was not the first time he had peremptorily imposed a diagnosis in his family. George had placed his wife, Isabella in the hospital after she gave birth at home — three times — deeming what was likely postpartum depression as behavior unsuitable for a wife and mother.

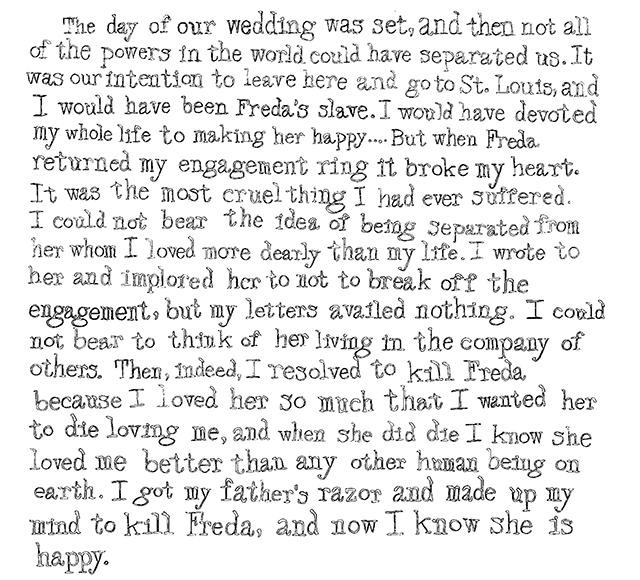

On the very night Alice had slashed a seventeen-year-old woman’s throat, her father convinced two formidable lawyers that his daughter could not be tried for murder. There was no denying that she had killed Freda — Alice had already confessed, and there were plenty of witnesses — but in 1892, her motive was utterly inconceivable to them. Alice’s insistence that she killed Freda because she loved her and could not stand the idea of anyone else having her, and that the young women had planned to marry, seemed nothing short of insane.

By the time Gantt and Wright emerged from Alice’s cell that evening, they had an interview in hand and a plan of action.

No one outside of the judicial system would be allowed to speak to Alice, and those within it would be closely supervised. By denying access to their client, Gantt and Wright could carefully manage Alice’s story, since any reports disseminated through the press could possibly set the tone for the entire trial.

Their first opportunity to steer the public narrative presented itself the moment Alice’s newly formed defense team exited the jailhouse. News of a well-to-do white woman turned murderess were rapidly circulating through Memphis. Gawkers and journalists alike had already begun swarming outside of the building, desperate for any information about what was rumored to have been — to use what would become one of their favorite words for the case — an unnatural crime. They were desperate to hear Alice’s side of the story, and happy to accept the version Gantt and Wright were peddling. And the defense was more than happy to see the press and spectators repeat what they had heard as if it were firsthand account, as if they had heard the words spoken by Alice herself.

But Gantt and Wright had no intention of giving them the whole statement that night. Borrowing from a publishing format usually reserved for works of fiction, they serialized Alice’s interview, releasing it in bits and pieces over the next few days, keeping reporters and readers tantalized and hungry for more. The defense made good use of the time in-between the daily publication, seeking out a team of medical experts to add weight to the plea they hoped to file — present insanity — and all in time to be printed in the next installment.

Gantt and Wright were no strangers to mass media. They understood the public’s bottomless desire for sensational news stories, especially for crimes of passion. They correctly anticipated that the Mitchell case, a cornucopia of scandalous detail, would attract unprecedented attention. The inescapable din of news reports, gossip, and fervent speculation would surely reach the ears of potential jurors.

Steering the press’s narrative was also the quickest way to get to Judge Julius DuBose, who presided over all the cases in the jailhouse. It was easy enough to predict he would turn to the Memphis Public Ledger first. Not only had he started his career as an editor at the Public Ledger, but the paper had the clear advantage over all the other outlets: It was the first, longest running, and most popular evening paper in Memphis. If any newspapers were going to influence the judge, it would be the Public Ledger. The reports and editorials in the paper not only had the potential to spin their own version of the latest details in the case, but more importantly, serve as a daily performance review of the judge himself. It was possible that, after reading the nightly paper, Judge DuBose would take its opinions into consideration as much as the evidence presented in court.

In 1892, there were more than a dozen papers in Memphis, all of which were owned by local white men who wielded power in various realms. This was business as usual in the press; even Wright, just a few years earlier, had gladly stepped up as one of the first investors in the Memphis Commercial. Powerful Memphians backed their pet publications in order to further their business, personal, and political agendas. These competing factions modeled themselves after New York’s lucrative, mass circulation papers, where advertisers paid top dollar to appear next to a sensational story, in turn sending the newspapers’ circulations soaring.

This was certainly the practice of the Public Ledger and the Commercial. But to be truly successful in shaping opinions statewide — and as it would turn out, around the nation — Gantt and Wright would have to win over the Memphis Appeal Avalanche.

The Appeal Avalanche was the largest morning paper in the city, and made bold claims on the entire state of Tennessee. Though just a couple of years old, it possessed two things no other paper in Memphis had: a linotype machine and an exclusive deal with the Associated Press. The linotype produced an entire line of metal type at once, a far more efficient and faster means of publishing than the old industry standard, the manual process of setting type letter-by-letter. The Associated Press was around forty years old by the time the Appeal Avalanche joined, and the news cooperative had enjoyed a legendary reputation for dramatically increasing the transmission of news across the country since the Civil War.

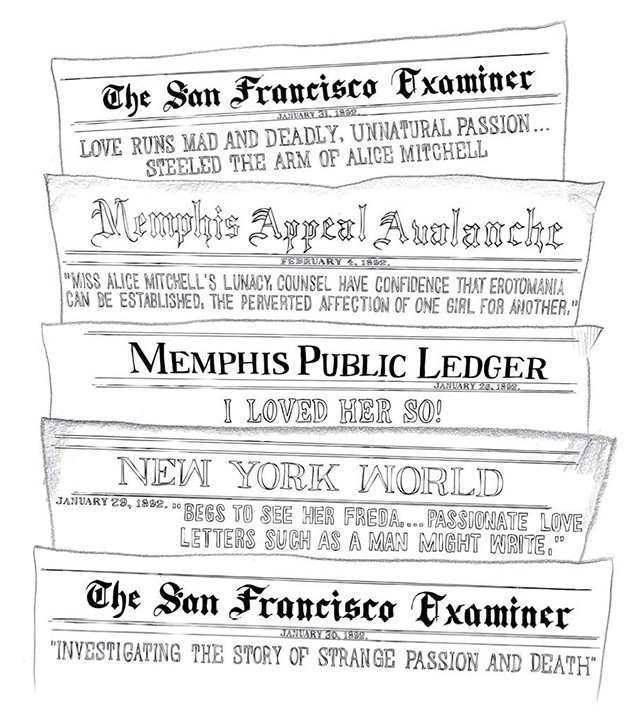

Just before midnight, local papers sent what little information they had about the murder of Freda Ward through the wire, and by morning, big urban dailies in major cities were already desperate for more. Nothing in Memphis had ever attracted such national interest, and thus none of the national, mass circulation papers had reporters stationed in the vicinity. As they scrambled to tap local journalists, the largest, most far-flung American newspapers, including the New York World and the San Francisco Chronicle, ordered their staff writers to board the next train to Tennessee.

In the days that followed the murder, nearly every newspaper in the country eagerly printed fact alongside fiction, eschewing even the most basic research efforts in favor of speedy transmission. The out-of-towners were exempt from local redress, and those newspapers took liberties with even the smallest details. The North American of Philadelphia aged seventeen-year-old Freda to nineteen, and reported that the young women’s estrangement began because “Freda’s friends considered Miss Mitchell ‘too fast.’”

The New York Times misspelled Lillie Johnson’s first and last name, identifying her as “Lizzie Johnston,” and offered a muddled timeline in which Alice first murdered Freda, and then cut Jo.18 Memphis readers would have immediately questioned the article’s sub-headline, in which the paper of record erroneously identified Alice as a “society girl.” In the social hierarchy of the South, slave-owning families who had made millions in cotton and horse breeding were “familiar figures in society,” not a merchant’s daughter. Similarly, Freda, the daughter of a machinist who had sought greater prospects up river in Golddust — and came from a family that was far less well-to-do than the Mitchells — was not a member of Tennessee’s semi-aristocratic class. Neither girl had made the guest lists at parties the Memphis elite staged on their sprawling estates, many of which still operated as plantations.

But local newspapers specialized in their own brand of creative reporting, including embellishments that read more like popular fiction than true crime. Judge DuBose’s former employer, the Public Ledger, described the murder scene with flourish:

“Grasping her by the hair Miss Mitchell pulled her head back, exposing the round, white throat. Again the keen razor was brought into play, and this time it did its work with frightful completeness. The girl was almost beheaded, and fell fainting to the ground, which was soon drenched with her rushing blood.”

The racial identifiers — the New York Times emphasized Freda’s “white bosom” and the Public Ledger spoke of her “white throat” — were visceral scare tactics used to remind readers that these were the kind of people they knew and cared about. Journalists knew that the story would be far less consequential to readers if the murderer and victim had been male, not white, or of lesser economic means. And if they could punctuate the scene with a subtly sexualized near-beheading, all the better.

To American readers in the 1890s, the most confusing part of the Mitchell case had little to do with inconsistent reporting. The early headlines emphasized how confounding the very idea of same-sex love was in the first place. Reporters relied heavily on words like “unnatural,” “strange,” and “perverted.”

When all else failed, reporters attempted to explain that Alice was “a man” in the relationship. Though, they conceded, not masculine in her dress or countenance, her supposedly hidden proclivity toward all things male was yet another way reporters could contrast Alice with “normal” young women. In an interview with the Appeal Avalanche, Gantt explained that Alice had quietly, but consistently, defied gender norms her entire life:

“…everything she has done, her peculiarities, whether during her infancy she played with dolls or other such toys in which the average female delights, whether she had a fondness for those of her own or the opposite sex, all of these will be circumstances going to show the state and quality of her mind.”

Newspapers enthusiastically accepted whatever scraps of information the defense tossed at them, and relied on an abundance of loose-lipped locals to fill in the gaps. The city was overtaken with intrigue, and there were hordes of Memphians who wished to weigh in on the murder. Some sought to correct erroneous material, but more often than not, they offered subjective observations. These opinions were often based on personal experience

with the Mitchells or the Wards, though as time went on, they were clearly influenced by what they read in the newspapers, too. Others, whose lack of connection to the case did not deter them from offering highly quotable views and speculation, were also tapped as ongoing sources. These unreliable perspectives were no more subject to fact checking than any of the other details making their way across the nation.

Neighbor John Perry offered what was likely a nebulous recollection of the Mitchell’s youngest daughter, combined with what he had obviously absorbed about the version of Alice now being discussed in newspapers as an insane murderess.

“I live next door to Mr. George Mitchell and have known Alice for nine years or more, and have never considered her strong mentally. Her manner has been always flighty and unsettled and her ways different from that of most girls. She was of an impulsive disposition, and given to doing very much as the present mood inclined her, whether it was to snatch up a rifle and stand about her yard shooting sparrows or to ride a bare back horse at break-neck speed about the premises. I have never seen anything about her conduct that was at all immodest, nor was she the least bit fast as regards to men. On the contrary, she seemed to care nothing for them and rather preferred the society of her own sex. . . . From a long and close knowledge of Alice Mitchell her act was that of an insane woman.”

Concerned citizens, and those with other sorts of motives, reached out to the authorities as well. The attorney general’s office received many letters, both signed and anonymous, riddled with suspect details, outlandish claims, and transparent lies. While the offices of the court and the police privately dismissed the more outrageous reports, they were more than willing to turn around and discuss them with reporters. Attorney General George Peters was constantly asked about a popular rumor that Alice Mitchell had sent the office a letter from jail, but Peters shunned it as “the ebullition of a crank.” Likewise, a Memphis detective relayed a phone call he received from an agitated man in Cincinnati who informed him that three years prior to Freda’s murder, Alice had “made love like a man to his daughter, now deceased.”

Relentless messages concerning the supposed unnaturalness of Alice’s motives were clearly working. In the mind of the public, she seemed endowed with an almost supernatural power to commit heinous acts, no matter the time or place.

The prosecution offered very little information beyond stating that Alice was of sound mind — a decidedly insipid claim next to the defense’s adamant plea; dramatic presentation of sensational, anecdotal “evidence”; and aggressive campaigning. Public opinion was leaning toward the defense, but Gantt and Wright had yet to play their wild card: the most incendiary part of Alice’s statement.

The Appeal Avalanche published this part of Alice’s statement under the headline, “WHO IS THIS JESSIE JAMES?”

Today’s readers are likely to interpret this confession as the unfortunate saga of a troubled, teenage romance turned deadly: Alice believed she had found her one true love, and that their commitment could withstand any challenge — or be immortalized by death. For some time, Freda felt the same way, or at least proved convincing enough that the withdrawal of her affections truly broke Alice’s heart. Her only solace was the assumption that Freda was bowing to familial pressure, and when she learned this was not the case, that Freda’s love had been fickle, Alice was determined to hold her to their agreement. If any part of her statement casts a doubt on Alice’s sanity, it is the conclusion, in which she claims to know Freda is happy to have been murdered.

But to Americans in 1892, her insistence on loving and wishing to marry and support a woman were, in and of themselves, clear signs of lunacy, and there was no shortage of physicians willing to corroborate that assumption. Still, in their efforts to create an airtight case, Gantt and Wright scoured Eastern Tennessee in search of the most prominent and influential physicians for supporting testimony. The prosecution had far less luck finding doctors to refute the plea, while the newspapers, sensing readers wanted some medical context, readily printed any theory that called itself scientific.

The first “prominent physician” quoted in a newspaper — or at least, the first one who made it to press — diagnosed Alice with erotomania, defining it, inaccurately, as “unnatural affection between two persons of the same sex.” Other doctors, also unnamed, would assert erotomania was a “malady of the mind” that could easily “lead on to murder.”

Whether or not the unnamed doctors’ quotes were fabricated by overzealous newsmen, their alleged interpretations of erotomania were as legally convenient as they were medically creative. For more than two centuries before Alice murdered Freda, erotomania had described “forms of insanity where there was an intensely morbid desire to a person of the opposite sex, without sexual passion.”

While the Mitchell case would eventually produce new meanings, Gantt and Wright would not rely on the diagnosis of erotomania. In fact, the lawyers would avoid any argument that contained even a hint of the erotic, and most certainly any that acknowledged actual sex acts. Sex between two women was not entertained, even as a theoretical proposition. The defense and prosecution, as well as most newspapers, tacitly agreed on this point: There would be no public discussion of anything even faintly sexual. Three years later, the English press would similarly cover the libel case Oscar Wilde lodged against the Marques of Queensberry, who left the writer a calling card inscribed, “For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite [sic].” Wilde’s sexual preference was never explicitly identified, but simply suggested through vague euphemisms, which included the very words the press seized upon and frequently applied to Alice — “unnatural,” “immoral,” and “indecent.”

That should not suggest the papers were unwilling to test the waters, even granting that Alice and Freda had experienced some “gratification of the perverted mental passion.” The defense, however, was always quick to push back against these claims, insisting Alice and Freda’s love was “purely . . . mental.”

Who was Alice Mitchell? Why did she kill Freda Ward? Was she a masculine murderess? A pervert? A fast and jealous young woman? Or was she insane, like her mother?

Just as the Mitchells insisted that the defense argue for Alice’s insanity, the Wards pushed the prosecution to maintain the opposite. “She was no more crazy than I am,” asserted Ada’s husband, William Volkmar, an “old Memphis boy” who had hosted Alice in his home.30 Alice said “I don’t care if I’m hung,” Jo Ward recalled, insisting the murder was premeditated, and carried out in cold blood. Neither quoted the writer Mark Twain, but they would have found agreement in his essay, “A New Crime — Legislation Needed.” Two years before Alice was born, Twain bemoaned the rise of the insanity plea, and how it allowed for otherwise unremarkable behavior to be recast as proof of an unsound mind.

“Of late years it does not seem possible for a man to so conduct himself, before killing another man, as not to be manifestly insane. If he talks about the stars, he is insane. If he appears nervous and uneasy an hour before the killing, he is insane. If he weeps over a great grief, his friends shake their heads, and fear that he is “not right.” If, an hour after the murder, he seems ill at ease, preoccupied and excited, he is unquestionably insane.”

But it was the prosecution’s case — and not the defense’s plea — that newspapers characterized as inconsistent and unconvincing. Attorney General Peters called Alice “fast,” citing jealousy over a man as a possible motive, but also claimed she was indifferent to men. At the very least, he argued that she was ill-tempered and vindictive, but certainly not insane.

By questioning Alice’s moral character, Peters challenged readers’ cherished notions of the Mitchell family’s respectability, and few outside the Ward family were interested in that perspective. The Appeal Avalanche soon reported that “the preponderance of public opinion is in favor of the theory that Alice Mitchell is insane.”

Months before the lunacy inquisition would officially commence, the defense could claim public opinion as its first victory. Mass media played an influential role in regulating the boundaries of American modernity, and such a high-profile domestic tale on public display provided a means to do so. The defense offered editors a message they wanted to propagate: Alice was a well-to-do white woman from a pious family who was neither bad nor fast, and did not deserve to be in jail among base miscreants of every race and class. The public most certainly refused to see her hanged, with her fine family looking on.

Of course, the papers could not uniformly align themselves with the defense. Debate was a useful strategy when it came to selling copies; it was in the newspapers’ interest to see that all positions were argued for vociferously. In Memphis, the Appeal Avalanche supported the case for insanity in lockstep with Gantt and Wright, while the Commercial often challenged them. If Alice had indeed loved Freda, the paper contended, she should be judged as a man would be, had he committed a crime of passion. She was legally responsible, they argued, “because she cowardly ran away. Had she been wholly irresponsible and insane, she might have acted differently after drawing the razor across Miss Ward’s throat.” The Appeal Avalanche countered that the ability to function in daily life was irrelevant, as was any talk of treating a woman like a man, maintaining that Alice was “the slave of a passion not normal and almost incomprehensible to well-balanced people.” On that point, the Commercial almost always retreated.

Before Alice even entered the courtroom, newspapers across the country had latched on to every detail, real or imagined, of what they considered a particularly lurid murder. But national fascination with the case was about far more than the death of a seventeen-year-old girl, or a desire for entertainment and spectacle. Same-sex love, passing as a man, and alternate domesticities challenged everything Americans understood, and were desperately holding on to, in the late nineteenth century. During the next six months, this domestic drama would put issues of morality, individual liberty, and mental health front and center, forcing people to have a stance.

But first, Lillie Johnson would have to be arrested, and Freda Ward laid to rest.

Alice+Freda Forever: A Murder in Memphis is Alexis Coe’s first book. In addition to being The Awl’s Hammer Time columnist, she has contributed to the Atlantic, the Paris Review Daily, Slate, the Toast, the Hairpin, and many other publications.

She’ll be discussing the book tonight at Housing Works at 7pm.

Top images via

The Value of Space

More facts about spaaaaaace in New York City, particularly in the newest wave of luxury buildings:

Space with no views at the Sterling Mason, a 33-unit condominium at 71 Laight Street in TriBeCa with 24 such areas, costs between $30,000 for a 28-square-foot storage unit (or $1,071 a square foot) to $55,000 for 94 square feet ($585 a square foot). … “Storage is no longer an afterthought,” said Elizabeth Unger, a senior sales director at the Corcoran Sunshine Marketing Group, which is marketing 56 Leonard and several other uber-luxury condos. “It’s as thought-out as designing a lobby.” And with many owners requesting storage space, parking spots and other extras, she added, “it’s also an income producer.”

Buyers at 56 Leonard who pay $72,000 for a storage cage will not actually own it, however. As in many new buildings with subterranean space, they are buying long-term licenses for their storage units and parking spots, entitling them to use the space as long as they are residents of the building and requiring that it be sold in the event of a move.

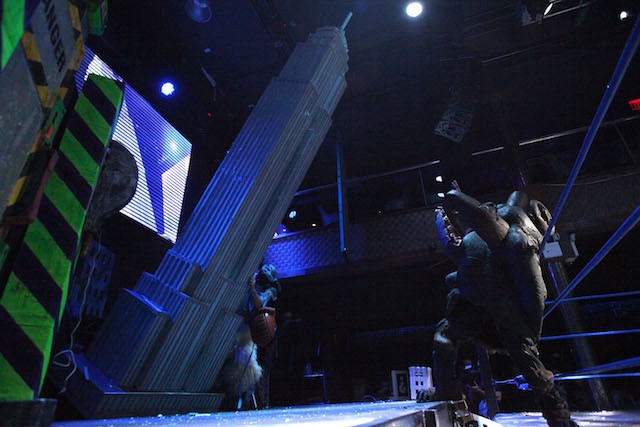

A Night at the Kaiju Big Battel

by Jared T. Miller

A couple of weeks ago, a battle between good and evil took place in a wrestling ring on Manhattan’s west side, when Silver Potato, a former Blockbuster video employee managled in a tinfoil-microwaving accident, fought off the minions of Dr. Cube, the mastermind of an evil kaiju cohort, who were pummeling Steam-Powered Tentacle Boulder. According to Kaiju Big Battel legend, regular wrestling matches, like the one between Silver Potato and his foes, prevent kaiju and their humanoid combatants from destroying earth’s cities by constraining them to a ring, so that the war between good and evil can be settled with minimal property damage. The event, “Shpadoinkel Mania XX,” marked the beginning of the live-action WWE-Godzilla-Japanese-anime hybrid’s twentieth season and fall tour.

#13 vs. Steam Powered Tentacle Boulder

The announcer Louden Noxious

Sekmet, Hell Monkey and Pedro Plantain

Pedro Plaintain vs. Sekmet

American Beetle vs. Gambling Bug

Dr. Cube and his Minions vs. Steam-Powered Tentacle Boulder

Silver Potato vs. Dr. Cube’s Minions

Steam-Powered Tentacle Boulder vs. #13

Jared T. Miller is a multimedia journalist in New York.

A Poem by Jennifer L. Knox

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Certainty Is Born of Pain

Biting down wrong would’ve done it.

Too many chips scarfed at happy hour.

Don Cucos’ two buck margaritas, 4–6.

I’ve never been big on chewing. I more like

chomp-chomp-chomp-gulp — a Hoover.

Maybe I’m trying to power through the meal

to the empty place on the other side where I can

stuff more in, no subtleties of pleasure slowing

me down. A komodo dragon unhinges its jaw

to swallow whole sick pigs and dozing deer.

Afterwards, it sleeps weeks as the prey’s shape

dissipates into its guts like the face on a melting coin.

I envy its contentment — or whatever you call it.

So who knows why, when I was nineteen, I got that

horribly swollen taste bud worthy of an ER visit,

but I do know when I cut it off with toenail clippers

it bled for days — hurt way worse — my tongue

needed a cast — and now when people speak

of piercing their tongues, I know I know

too much to follow them there.

Jennifer L. Knox’s poems have has appeared in The New Yorker, American Poetry Review and four times in the Best American Poetry series. Her new book, Days of Shame and Failure, is forthcoming from Bloof Books in 2015.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.