How To Fuck A Cooking Steak

Turn the lights down low and pour a glass of wine for the steak and a glass of wine for yourself. Candles aren’t strictly necessary but they do help set the mood. Ask the steak about its day, letting it talk for as long as it likes, only stopping the flow of the steak’s conversation when it seems like the steak wants you to ask it another question. Occasionally offer compliments. (If it’s a handsome steak tell it it’s smart; if it’s a smart steak tell it it’s handsome.) Every now and then brush your fingers against the steak absent-mindedly, but don’t withdraw those fingers too quickly. The steak should feel your heat. As the evening progresses and the steak warms up to you, continue to laugh and be close to one another. Offer the steak another glass of wine but never serve it more than it seems like it wants. When you feel ready to make your move, ask for the steak’s consent to perform an abbreviated butterfly maneuver. If and only if the steak fully and enthusiastically agrees, lay it flat on a cutting board and use your sharpest knife to make an incision in the steak’s middle that is roughly the size and thickness of what you plan to put inside the steak. Be firm but gentle, slicing rather than hacking or sawing. Once you’ve completed slicing the steak and the steak indicates that it still is willing to proceed, take it to the bedroom, crank up My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless, and bring it to as many heights of ecstasy as you and your steak can handle for the evening. Afterwards, tell your steak you will call it again even if you don’t plan to. The steak will know that you’re lying, but will still appreciate the effort.

Previously: How To Cook A Fucking Steak

How the Web Was Won

The Web is a Millennial. It was first proposed twenty-five years ago, in 1989. Six years later, Netscape’s I.P.O. kicked off the Silicon Valley circus. When the Web was brand new, many computer-savvy people despised it — compared to other hypertext-publishing systems, it was a primitive technology. For example, you could link from your Web page to any other page, but you couldn’t know when someone linked to your Web page. Nor did the Web allow you to edit pages in your browser. To élite hypertext thinkers and programmers, these were serious flaws.

— Paul Ford on the history of the Web and HTML5, the “markup we deserve”

A Prison for the Dead

by Chris Arnade

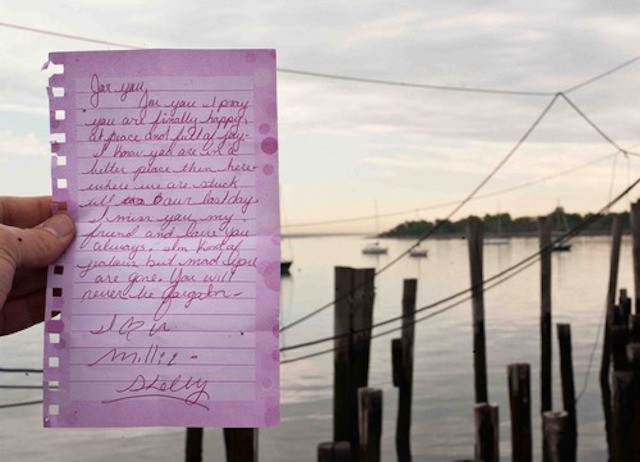

Millie, the last time I saw her

When Millie died last year, her foster mother was in a nursing home and her pimp was in jail. Nobody came to collect her body, so the city buried her where it has interred a million other unclaimed bodies: in a massive trench on an inaccessible, desolate shard of land in Long Island Sound called Hart Island.

Millie had spent New Year’s Eve walking the track — the empty part of Hunts Point in the Bronx, where the older prostitutes, who liked the quiet, worked. She stayed out until daybreak, alternating between getting into cars and walking up the hill to buy drugs with the money, then slept most of New Year’s Day. The next evening, she collapsed in the Tub and Tumble Laundromat, a place she often wound up when she didn’t have anywhere else to go. Before falling, she apologized to Ana, the manager and her friend, saying she was feeling ill. She was taken by ambulance to Lincoln Hospital.

She had no identification. She kept it, along with other important papers — mostly pink slips from the police — in an old Ziploc bag that was stashed in a small fence post on the empty street she worked. Nameless, she was admitted as a Jane Doe.

Millie with papers

A few days later, she died and her body was moved to the basement morgue and tagged BX97 — the Bronx’s ninety-seventh death in 2013.

Nobody came looking for her. Her thirteen siblings, cobbled together from various foster homes, were acclimated to her disappearing for long stretches of time, after which she would re-materialize, just released from jail or looking for a home to detox in. Her friends from the streets, the ones she called her sister or her aunt or her mother, assumed she had gone into rehab or jail. A few feared she had died — she had a massive abscess the length of her arm that worried them — but they didn’t have phones or computers to look for her.

Two months after she died, Millie was buried by inmates from Rikers, another body piled on a million others in New York City’s public cemetery, the last stop for those who die alone or destitute.

On the streets, little is certain. Hart Island magnifies that uncertainty, adding one more thing to fear about death — a place where you are buried in a trench that nobody can visit. Millie’s friend Pepsi talks often about it. “I don’t want to be buried like a stray dog,” she told me. “I hope to God and pray that I don’t get treated like that. I want the decency to be buried by those who love me.”

It’s little coincidence that Hart Island feels like a prison for the dead: It is run by the Department of Correction. Everything about it is intentionally ambiguous: It is illegal to photograph (images come from photographers flying in rented helicopters or using telephoto lenses in kayaks); the names and stories of the people buried there are only now being made available to the public; and nobody can visit burial sites.

Some take precautions to avoid winding up there. “I had gotten ten bags of great shit. I knew it was all going in me and that it could end that night,” Pepsi said. “So I wrote my father’s phone number in marker on my stomach before shooting up for the paramedics to see.”

Jackie

In August, Jackie, who also worked for Millie’s pimp, went into a coma after shooting a bundle of really good dope in a crack house. An ambulance was called and Jackie was taken to Lincoln Hospital. She was twenty-four years old when she died. Nobody knew her real name; she had spent her last four years in Hunts Point, shifting between a shelter and the streets, where she was just Jackie. Jackie with lupus.

Without the information needed to track or claim her body, Jackie would’ve lay unclaimed, eventually tagged BX #,###. After two weeks in the hospital morgue, if still unclaimed, a body is shipped to the City Medical Examiner’s office where an autopsy determines cause of death. For Millie, her death was due to “Bacterial Endocarditis of tricuspid valve due to intravenous drug abuse.”

If still unclaimed after roughly two months, the body is moved by a refrigeration trunk, filled with other bodies, to City Island in the Bronx, then loaded onto a ferry for the half-mile ride to Hart Island.

On Hart Island, inmates, bussed over each morning from Rikers, place the bodies in wooden boxes that have been made by other inmates. The boxes are lowered into a large, standardized trench, seventy feet long, twenty feet wide and six feet deep, dug by backhoes. When no more boxes can fit, the trench is covered, and a new one is dug to accommodate the next set of bodies. This process has been ongoing, more or less uninterrupted, since 1868.

You can, if you are very determined and organized, visit a sliver of Hart Island that is unused for burials. Every third Thursday of the month, the ferry normally used to transport remains brings passengers for closure visits. These small visits are a recent change, due to the twenty-year effort of one artist, Melinda Hunt, and her non-profit, the Hart Island Project, whose goal is to bring awareness, transparency, and a measure of dignity to the process of dying poor in New York.

Ferry to Hart Island

I offered to bring Millie’s friends, but none had the proper photo ID or were comfortable presenting it to corrections officers. They did give me a few items to bring: A letter, a small bottle of water from the open hydrant Millie used to cut her heroin with, and a half dollar. “What is a better memorial to a street whore than a ripped dollar bill?”

The letter read:

For you I pray you are finally happy, at peace and full of joy. I know you are in a better place then here where we are stuck till our last day. I miss you my friend and love you always. I’m kind of jealous but mad you are gone. You will never be forgotten.

I love you Millie

Shelly

On the island, you can walk fifteen yards from the ferry landing to a small fenced-in plot with an awkward looking gazebo and a single ceremonial tombstone, inscribed with scripture that is dedicated to the collective dead. Small dirt roads, shielded by Department of Correction vans, run off from the ferry landing, the view beyond blocked by rows of trees and decaying buildings — the remains of old institutions for the poor and sick.

I read the letter to Millie, tore it up, and sprinkled it and the water around the fenced-in plot. Then I sat on the gazebo and listened to the sounds of gunfire echoing continuously from the the city’s police training range, just across the water.

Hart Island seen from the Bronx

In the Trenches of the Facebook Election

For a profession locked in a perpetual psychodrama with Facebook, I think journalism underestimates Facebook. It’s not that journalists don’t pay enough attention to the site (god no, lol), just that, as a journalist, your perspective is obscured, and it’s difficult to conceive of Facebook from the outside. You experience it through your profile, your site’s official page, your stories, or your analytics suite. It feels both unfathomably more powerful than you and yet somehow all about you; your experience is acute and personal but so are the experiences of other users, which are therefore inaccessible. David Carr’s characterization of the media as wary of working as “serfs in a kingdom that Facebook owns” is doubly apt for its implication that Facebook’s kingdom can only be as large as the publishing world it is apparently subjugating.

This, maybe, is why journalists are so bad at seeing where they fit into the grand scheme of social media feeds — that is, that they now compete, head to head, with videos and games and comedy and posts from friends and family for a limited amount of attention. Believing that the dominant social software does not think you are in any way special is difficult to reconcile with the conventional wisdom that it also controls the future of your industry. Together, these ideas are fatal to the ego, and so they cannot both be true.

So I think this prediction, about the so-called Facebook Election, is reasonable:

At some point in the next two years, the pollsters and ad makers who steer American presidential campaigns will be stumped: The nightly tracking polls are showing a dramatic swing in the opinions of the electorate, but neither of two typical factors — huge news or a major advertising buy — can explain it. They will, eventually, realize that the viral, mass conversation about politics on Facebook and other platforms has finally emerged as a third force in the core business of politics, mass persuasion.

First of all, who knows, anything could happen, two years is a long time and the internet is an unstable place that could be completely overtaken by a fresh horror at any moment.

But SETTING THAT ASIDE: Ben Smith wrote this piece for BuzzFeed, where I used to work, which is one of the most successful publishers on Facebook, but that also has a healthy and pragmatic institutional understanding of the difference between the all-consuming social platforms and the websites that supply them with content. It is not boosterism to say that Facebook will matter to the 2016 election, in other words, but realism — a demonstrable possibility that everyone on the internet will have to deal with in their own way.

Less situationally aware publishers looking forward to the next election might also agree that Facebook will play an extremely important part in it, but only to the extent that they believe people will use it to share their stories. This is a comforting view: it preserves a familiar set of competitors, and imagines the near future to be a matter of slicing up a slightly bigger version of the same pie, served at a slightly larger version of the same table. Facebook is just a conduit through which rightful journalistic influence travels! Nothing to worry about, great job, etc.

But Smith suggests a different outlook, in the culmination of a decades-long shift:

What is beginning to dawn on campaigns is that persuasion works differently when it relies on sharing. It is a political truism that people are most likely to believe what their friends and neighbors tell them, a truth that explains everything from sophisticated and earnest door-knocking efforts to malign email-forward whispering campaigns. And the social conversation favors things that generations of politicians have been trained to avoid: spontaneity, surprise, authenticity, humor, raw edge, the occasional human stumble. (Joe Biden!) As mobile becomes increasingly central to the social web, I suspect that more voters in 2016 will be persuaded by a video in their Facebook mobile browsers than by any other medium.

This “third force,” an enormous and incoherent and unpredictable set of social media interactions, is neither inherently nor deliberately biased toward the existing media, political or not. Facebook’s attitude toward journalism is the same as its attitude toward everything else: The thing that grabs your attention and holds it the longest, that is most likely to be shared again, is the thing that wins the next slot in the endless algorithmic draw. And I’m not sure most existing journalistic media companies have reckoned with just how completely this diminishes their role in writing and perpetuating political narratives! (Last time around the political media was still writing “_____ Goes Viral” posts; today, what big story couldn’t you headline that way? What about in two years?)

So how does this Facebook election actually go? If 2008 election internet was all about checking blogs for aggregated gaffes and 2012 election internet was all about novelty Twitter accounts, what are we in for in 2016?

Some background: The most successful new-new media companies, in raw traffic terms, are the ones that create content meant primarily to be shared on Facebook — that is, sites that appeared in the last few years, and that would not exist at all, as concepts or as businesses, if not for Facebook. Some of them are Zynga-like media startups, such as PlayBuzz, which seems to be an extended experiment in social media story formats. The most common are just profoundly cynical general interest share mills, which you’ve probably seen in your Facebook feed by now (read this interview with the creators of Viral Nova for a vivid example).

Another breed of sites infuses its highly engineered posts with a deliberate ideology: Upworthy, arguably the first pure Facebook publishing experiment, promotes gentle-left activist causes and ideas. It pioneered the Facebook form, with teasing headlines, emotional hooks, the “curiosity gap,” etc. But it also pioneered, or refined, the concept of the rhetorical Facebook-sharing payload: Post one of its embedded videos, and you can show your peers that you are right-minded and progressive. Maybe even shame them a little!

Many of these posts contain a conscious appeal to identity, which, in the context of new media companies, is a fairly fresh and powerful idea (though in politics, maybe the oldest). Some sites, BuzzFeed in particular, have played with identity through a focus on entertainment — “Ways You Know You’re A _______”, “Signs You Grew Up _______” — but Upworthy, founded by the former Executive Director of MoveOn.org (who also coined the term “Filter Bubble”), figured out how to apply it to progressive politics.

Among the many Upworthy clones, one stands out, in part for sitting at the other end of the American political spectrum:

The Independent Journal Review landed big. It is currently the 14th-most-shared site on Facebook, a couple slots in front of MTV and CNN (Upworthy, still enormous, no longer ranks in the top 25). It is brashly and proudly conservative, offering charged and familiar right and center-right takes on the news of the day, along with feel-good videos of a slightly different flavor than Upworthy’s: stories of prayers answered versus stories of oppression overcome; tales of values upheld over examples of odds beaten. The difference, when it comes to positive content, is mostly a manner of sensibility — IJR and Upworthy both recognize just how many people want to share things that make them feel good and, just as importantly, understood.

In the context of a customized feed, where each story is algorithmically selected based on the likelihood that you will engage with it, content-marketed identity media speaks louder and more clearly than content-marketed journalism, which is handicapped by everything that ostensibly makes it journalistic — tone, notions of fairness, purported allegiance to facts and context over conclusions. These posts are not so much stories as sets of political premises stripped of context and asserted via Facebook share — they scan like analysis but contain only conclusions; after the headline, they never argue, only reveal. You don’t post a stunt video headlined “ISIS-Flag Waving Man Shouts Propaganda at a College. No One Cares. Then He Pulls Out Another Flag…” to let people know that the stunt occurred, or to convince other people of anything in particular. You share it because it confirms your beliefs about higher education, or liberals, or your ideological opponents’ attitude toward the Middle East. (This is the most-shared article on IJR right now, with nearly 300k Facebook shares.)

Partisan media has always done well online, but Facebook puts a large casual partisan audience within reach of anyone willing and able to scoop it up. When this audience starts paying a little more attention, as the election heats up and its fringe voices inevitably creep inward, they will be looking for things to share. Upworthy and IJR and countless similar sites will be waiting, ready to help them show their Facebook friends Where They Stand.

Among those similar sites will be Western Journalism, a smaller, more recently successful operation that has nonetheless become the 25th largest publication on Facebook. Western Journalism takes the social media identity site to its logical conclusion, offering readers a way to broadcast not just their views and political identities, but something a little darker.

IJR has dabbles in this type of content, too — evocative, coded, intentional, and between you and me. It publishes an awful lot of stories about “thugs”:

But Western Journalism goes all the way, all the time. Even its name is coded. The site, according to its about page, is published under the auspices of the Western Center for Journalism:

WesternJournalism.com is a blogging platform built for conservative, libertarian, free market and pro-family writers and broadcasters by the Western Center for Journalism (WCJ).

The platform hosts hundreds of bloggers, and our content is widely distributed using social media. In 2013 WesternJournalism.com grew by 103% and served 41,486,142 page views to 13,479,014 unique visitors.

The foundation was established by Joseph Farah, arguably the most persistent of the Obama birther conspiracy theorists, and is run by the legendary and ruthless conservative operative Floyd Brown.

Farah — who founded WorldNetDaily — and Brown are neither web geniuses nor social content gurus. They are, however, seasoned and effective marketers of intoxicating ideas that answer intoxicating prejudices, and they recognize an opening when they see it. They are among the first in their cohort to realize the magnitude of the Facebook opportunity as it relates to conspiracy and insinuation. Chain letter culture has been bubbling beneath Facebook’s surface for years; if Western Journalism is any indication, it’s ready to have its moment, just in time for the election of the next leader of the United States of America.

In other words, for a perpetually organized set of political and quasi-journalistic organizations — the horrible influence apparatus that stirs every four years — 2016 will be less about attack ads and TV talking heads and Driving the Narrative than it will be about dog-whistling from the News Feed. 2016 will be about internet content that hits you by surprise and then tickles your lizard brain. Think of the PAC-written Upworthies! Imagine viral Swiftboating.

This effect will be felt more acutely if the current Facebook video trend bears out. Check your feed with an eye out for this: mine is already dominated by clips. Not posts about videos shared on Facebook, or YouTube videos embedded in Facebook, but videos uploaded directly to Facebook. At the time of writing, they comprise about half of the media in my feed: They’re short comedy sketches from BuzzFeed, animal clip compilations from the Huffington Post, news clips from the BBC, music clips from bands and DJs my friends follow, and strangely labeled viral comedy content that doesn’t obviously come from anywhere at all. They are staggeringly popular even for viral posts, which makes sense: The purpose of much of the written viral content over the last few years has been to convince readers to leave Facebook to watch a video, and now the videos are just right there, and start playing before you even know what you’re looking at. It’s all the grabbiness of social media with all the numbing qualities of television. It’s powerful.

It’s early days for Facebook video, and the stuff that seems to be working best right now conforms to things people simply like and like to think about themselves. It’s nice! It is also coming disproportionately from journalistic entities, even if it’s mostly not journalistic content; maybe they were just the first people to figure it out. But don’t confuse earliness for destiny: In video as in text, content is content. Just as headlines learned to shout and soothe and grab and affirm in that particular News Feed way, these short videos will adapt to their newer, louder, more competitive version of the internet attention market — a market that feeds the political conversation, ads and smears and analysis and news and all, through a single, flat stream.

The ᴄᴏɴᴛᴇɴᴛ ᴡᴀʀs is an occasional column intended to keep a majority of ᴄᴏɴᴛᴇɴᴛ coverage in one easily avoidable place.

New York City, November 19, 2014

★★★ “The sun puts water in my eyes,” the three-year-old lamented, as the morning brightness met his congested head. The floors were cold underfoot. Crows, their throats bronze in the strong light, perched on the television antenna of the apartment block to the west. Now the leaves were bright red down on a cross street. Some distant birds flapped and glided on the wind, too quickly to find on the binoculars. At sundown, the northern sky glowed as strongly as the southern. A worker swept up dead leaves below the lumber frames awaiting the sidewalk Christmas trees. A Hampton Jitney stood in a no-standing zone. The supermarket was not warm enough to make the case for taking off the knit hat. The crosswalk signals were sticking with both icons showing at once. A dry, gloveless hand whistled when blown on.

Usage Guidelines Secondary

“You don’t use fighting words and then become really surprised that it’s caused a fight. If I said, ‘Fuck you and your mother with a stick,’ you’d say, ‘Whoa, Jack!’ And then I couldn’t say, ‘I’ve just been lynched.’”

New York City, November 18, 2014

★★★★ The only trace of the past day’s soggy unpleasantness was a curbside puddle or two. The light was golden and abundant, the chill on the wind wintry, but not winter. A fruit vendor wore fingerless gloves. Down against the Puck Building, a vaping man issued a thick white plume. The maple trees were still densely crowned with pale yellow, even as the street and sidewalk filled with dry yellow leaves, fallen since the rain. Deep into the afternoon, the bright blue sky shone down through the office windows, and rolling up a shade brightened the area noticeably. Then night fell like a guillotine, after the last pardon was exhausted. One bright star shone near the zenith. The cold made the nose run and brought up a dry cough. The maple leaves were white under the yellow streetlight. Straight lines glinted on the top of a puddle where a skin of ice was forming.