How to Die Slowly in America

As America enters its second season of Obamacare enrollment, a poll released Monday confirms that for the first time, a majority of Americans want the Affordable Care Act fixed, rather than repealed, owing to its visible successes. Unquestionably, the law can be improved. Among the many harms caused by opponents of the Affordable Care Act, one of the worst can be traced back to the efforts of Sarah Palin, who launched the phrase “death panel” into the public consciousness in an August 2009 Facebook post:

The America I know and love is not one in which my parents or my baby with Down Syndrome will have to stand in front of Obama’s “death panel” so his bureaucrats can decide, based on a subjective judgment of their “level of productivity in society,” whether they are worthy of health care.

Palin was referring, however nonsensically, to a provision of the ACA that would have reimbursed doctors for discussing (discussing!) end-of-life care with Medicare patients and their families: things like palliative care, hospice care and when to suspend treatment in case of a mortal illness. Families don’t receive this kind of counseling as a matter of course, and they should, for so many reasons — we spend too much money trying to rescue bodies that are too far gone to save; it’s cruel to make families endure the end of hope and the end of life in the same moment; too many people’s last moments are tortured, not peaceful. But Palin’s lies — that is what they were — created such a firestorm that those provisions were withdrawn from the final law. So now, an area of medicine that remains woefully inadequate for many Americans will remain so, even in the face of an opportunity to develop and expand it.

My father died twenty years ago, of kidney and liver failure caused by chronic nephritis of unknown origin. He had been sick for decades, with years of dialysis, surgeries, complications, and many preliminary skirmishes with death. We spent many weeks hanging around the intensive care waiting room, where we saw families gather daily to endure every kind of grief and fear — and sometimes to fall sobbing with relief into one another’s arms, half-crazy with the happiness of an impossible recovery. When it all got to be too much we’d go downstairs to the fourth floor, the softly lit maternity ward, and admire the newborns in their rows of bassinets, and bask gratefully in the pleasure and hope all around them.

My father was only in his forties when he started getting sick, so it never occurred to either of my parents that he would in time become too sick for a kidney transplant, or that there would be so much surgery, so many complications, and so much pain. Crisis followed crisis; we had a few miraculous recoveries of our own. But all told, it was a slow, inexorable decline. And then, many years after we’d become inured to living so near my father’s death, the night came when my mother and I were unaccountably shocked to find that all the options had run out.

It was very late, a warm quiet spring night, and my father was in a coma. Dr. Warner was with us to help; there were forms to sign and machines to turn off. Even after all the machines were silenced, the intravenous medications and solutions withdrawn, my father breathed on: an entirely inhuman sound at the end, grating and raw. This surprised the nurses, how it took so long — perhaps twelve hours.

I had to go home in the meantime to look after the baby; when I returned, it was over. My father’s was the first corpse I ever touched. I’d never really believed until then that there was such a thing as a soul; that is, if you’d asked me I would have said yes, I think maybe yes. But it was not until I returned to the hospital — too late! as if it mattered — that I had the sense of his body as empty. (As I kissed his very slightly oily, freezing forehead it was stunning, the inertness of this cold, dry head, once so full and so hot, like a bull’s, charging headlong into the whole world.) His body like the shell of a hermit crab, nobody home; recently occupied, thrashing, bleeding, suffering, laughing, pleading, rasping — not only still now but abandoned, empty.

Bodies, they’re so weird! You’d never think so from watching television or movies but they go wrong all the time — stuff grows in and on them, they leak, they develop cracks and fissures, or simply stage a mysterious internal revolt. But on TV, people die all at once: They get shot and collapse very neatly; they hardly ever scream or bleed, and when they are sick they deteriorate just as neatly, with a little pallor and a little bruising around the eyelids. Then they tenderly die — after a little speech! The real thing isn’t remotely like this; not even Quentin Tarantino could make a realistic entertainment out of the crushing boredom and horror of real chronic illness, with its hemorrhages and ruptures, stench and suppuration. The person you knew disappears entirely, sometimes to reemerge from a miasma of pain and terror days or weeks later. Sometimes not.

Technology can’t always save us. As Atul Gawande wrote in 2010 we treat and treat, but, “ultimately, death comes, and no one is good at knowing when to stop.” In my father’s case, we had waited too long to stop; what his body endured was like something out of a Bosch painting. The poor guy. Broke even the hearts of battle-scarred doctors and intensive care nurses. Strangely, though, after he died, I realized how much I would miss being at the hospital every day, because it is the true IRL. I’d been learning something every minute, my head held fast, like that of Alex DeLarge, so I couldn’t look away. Ordinary “reality” had come to seem by contrast surreal, fairy-tale-like.

Politics have little place in hospital beds, but it’s clear that they will continue to distort the conversation we might be having over health care, a conversation about the practice of medicine, and about patients and their families; about real people, and what really happens to them in the hospital.

Photo by Dan Cox

New York City, December 3, 2014

★ Mist lurked above the buildings and then withdrew, leaving dimness and dampness below. What the chill had lost in intensity it made up in its ability to penetrate. The water returned as a drizzle, verging on scattered rain, and then as full rain. The rain diminished; the cold increased. The newest excesses of Lower Manhattan were neatly chopped off where they reached above the older skyline, into the once-more-lowering gray. By the commute, the rain was entirely gone, and clouds moved surprisingly fast across the low gibbous moon.

Every Bug Story Is an Outbreak Story

Every Bug Story Is an Outbreak Story

A spec script for an Outbreak sequel, set in India, by the New York Times:

A growing chorus of researchers say the evidence is now overwhelming that a significant share of the bacteria present in India — in its water, sewage, animals, soil and even its mothers — are immune to nearly all antibiotics.

“India’s dreadful sanitation, uncontrolled use of antibiotics and overcrowding coupled with a complete lack of monitoring the problem has created a tsunami of antibiotic resistance that is reaching just about every country in the world,” said Dr. Timothy R. Walsh, a professor of microbiology at Cardiff University.

Health officials have warned for decades that overuse of antibiotics — miracle drugs that changed the course of human health in the 20th century — would eventually lead bacteria to evolve in a way that made the drugs useless. In September, the Obama administration announced measures to tackle this problem, which officials termed a threat to national security. Indeed, researchers have already found “superbugs” carrying a genetic code first identified in India — NDM1 (or New Delhi metallo-beta lactamase 1) — around the world, including in France, Japan, Oman and the United States.

Clutch your antibiotics tightly, but do not take them.

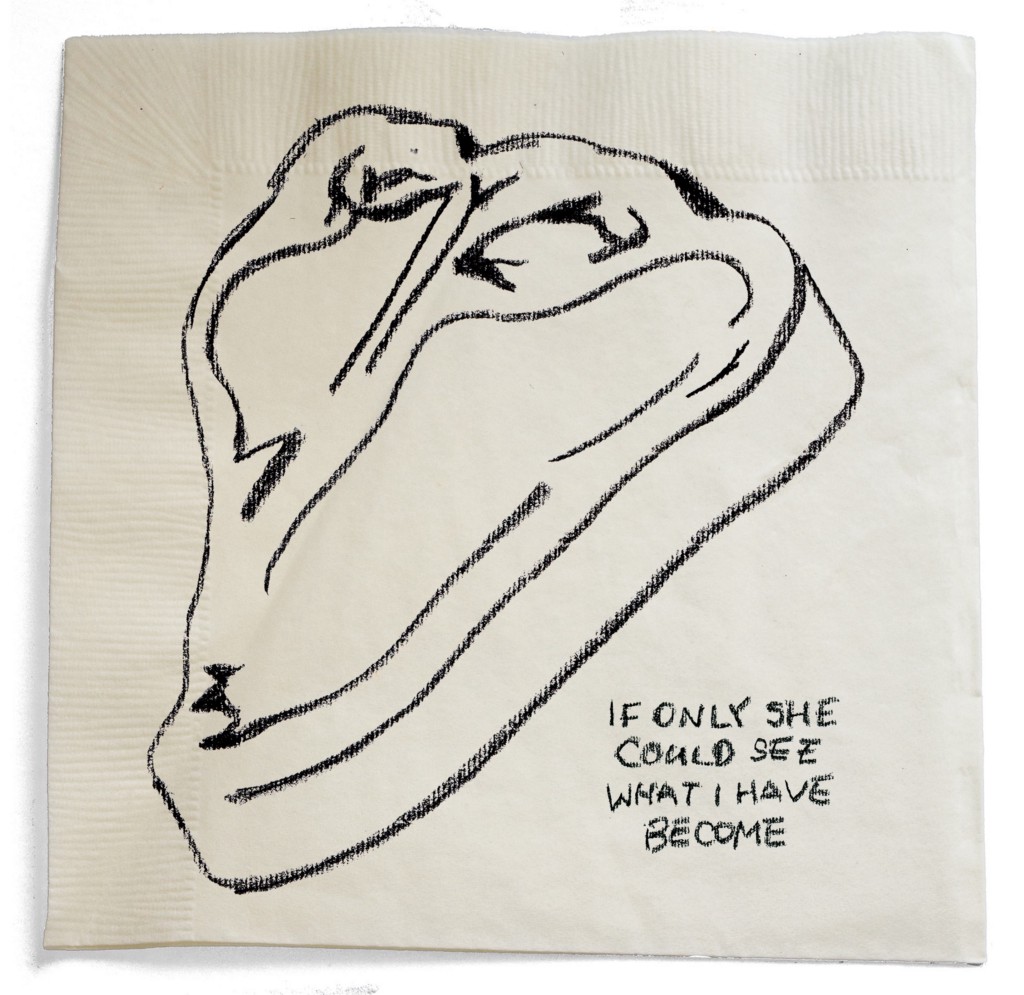

The Diary of a Self-Hating Meat Eater

by Gavin Tomson

Author’s Note: The following are excerpts from a diary that I found in the pocket of a black trench coat at a thrift store in Oslo, Norway. I have translated the diary from the original Norwegian (Bokmål). For the sake of the diarist’s privacy, I shall not provide his name. I shall, however, note that the diary contains a few visible food stains, and that here and there the diarist has illustrated the foods responsible for these stains. Also I shall note that the diary smells repulsive. It smells like my dad’s socks.

November 2,

The hollowness has returned. Ulrikke has left me. Grier’s visiting his girlfriend whom I’m sure is not real in Brussels, so now I have the apartment to myself. Today the sun set at 4 and it won’t rise until 8 in the morning. I feel like a submarine at the abysmal bottom of the sea. When I try to talk to people, I send out unanswered bleeps and bloops. I texted Ulrikke today, “im sorry.” No reply. If a submarine texts his ex at the bottom of the sea and she doesn’t reply, is he any less alone? For dinner I made a stir-fry: diced onions, mushrooms, red pepper, ginger, dark soy sauce and various ‘ethnic’ spices. I added medium ground beef and cooked it slowly, tenderly, sensuously, sizzling in butter. I cooked the beef knowing that beef makes me gassy. Anything to fill this hollowness.

November 6,

Lay in bed all day, curtains closed and caressed by the darkness, stuck in thought loops about Ulrikke, sweet Ulrikke, the one who got away. Recalled two lines from a poem by H.D: Like a bird out of our hand / Like a light out of our heart…

My boss called around noon to ask why I wasn’t at work and I told her I was bedridden with a migraine. I said, “The pain is intolerable,” which was true. Grier keeps a jar of distilled water in the fridge because according to his bullshit Ayurvedic diet, tap water contains either too many or too few negative ions. After my boss called I decided to add to the jar some tap water. Let’s see if he dies from tap water. For dinner I made chili with red beans because red beans make me shit and I yearn for a shit so satisfying it feels like Satan himself has left my body. Tomorrow: buy floss, cigarillos, chewable stool softeners (cherry), gum.

November 14,

Grier has returned. When he arrived I was making a ‘bad’ ham and white bread sandwich. He gestured to give me a hug, but I said I wasn’t in the mood. He doesn’t understand my moods. He doesn’t feel moods. He’s bubbly as bubble wrap. I want to pop all his bubbles. Are these ‘bad’ thoughts? Am I ‘bad’ person? The ‘bad’ ham contained a litany of preservatives; probably at least 6 were carcinogenic. I read the ingredients on the pack of meat and thought, Cancer. I thought, I will die of cancer. I thought, My libido is my cancer.

November 15,

Grier is really getting to me. His girlfriend, the Flemish med student whom I’ve never met because she does not exist, bought him a record player as an anniversary gift and all day he’s been playing The Beach Boys’s Pet Sounds on repeat. “We could get married / And then we’d be happy.” How much of a naïf do you have to be to hear that and not laugh? Grier told me that he finds something “beautifully despondent” in Brian Wilson’s naivety. I told Grier that he looks like a “Beach Boy who got trapped with a Hardy Boy in the same pod that turned Jeff Goldblum into a fly in The Fly.” Afterward I felt guilty even though Grier’s an asshole. I cooked salmon sausages that I found in the freezer. I burnt their outsides but their insides stayed frosty, possibly undercooked. Cutting the sausages into pieces and sort of gagging at the frosted pink middle, I whispered to them, “You’re not so different, you and I.”

November 17,

Yesterday I made another stir-fry. I cooked the pork in fish oil. This morning I awoke after dreaming of Ulrikke to the smell of the fish oil and thought, It’s the closest I’ll ever get to her vagina again. I thought, Oh, unrequited. I thought of that System of a Down lyric, Why have you forsaken me?

November 19,

These days I get Huffington Post comments. I get the anger. Read a tweet today that said, “Hell is other people’s Huffington Post comments” and responded, “therefore, i belong in hell.” Afterward I decided that I wouldn’t eat dinner because I’m ‘bad’ and don’t deserve dinner. Around midnight, though, I couldn’t take it anymore. I booked it to the nearest 7-Eleven and bought beef jerky because it seemed like the food product closest to poison. It tasted like how I imagine human flesh would taste. I thought, This is Grier that I’m eating. I thought, This is Grier’s forearm muscle. I thought, Grier died due to tap water poisoning and now I’m eating him in a 7-Eleven. Tomorrow: orthopedic insoles.

November 26,

Wandered Grier’s room for a while today, perusing his things. Realized he keeps mothballs to protect his Ethiopian textiles. Realized I have no idea what he does for a living? I think it has something to do with programming, but what actually is programming? I think, Programming, and then I think, Keanu Reeves. I think, Programming, and then I think, Give me the blue pill or the red pill or both pills if either can make me less depressed. Does Grier wear fingerless gloves when he’s programming? Does Grier keep a consistently clean anus? I think I’m developing a fever.

November 27,

Ulrikke, I wonder where you are in this world?

November 28,

Today Grier bought a vegetable juicer. I watched him drink a cabbage.

November 29,

Walked halfway to Ulrikke’s new flat in Grünerløkka today and then stopped, looked up at the forlorn winter clouds, thought, Do I want to be an artist? Thought, Is it too late to be an athlete? Thought, What is closer to truth, a bon mot, or a body in peak physical condition? I decided that buying basketball shoes would make me feel lighter in the world, The unbearable lightness of being, etc. — so I stopped at a Nike store and spent like 1500 kroner on a pair of Michael Jordans. The little man on the shoe — I think it’s ‘Mike’ Jordan himself? — appears to be flying. He’s shaped like a star. A superstar. I want to be elevated. Why do this to myself? I am the architect of my own misfortune. Why not get high? I think I’ll get high. Tonight I’ll do MDMA and actually eat something healthy. I’ll write down all my positive thoughts and read them tomorrow, to make myself feel that deep down I’m OK. Yes. This is a plan. This is a plan to get lifted, like Michael Jordan.

November 30,

Did MDMA last night. Cried for an hour in the bathtub. Wrote only one thing down: FORSOOTH.

Illustration by Vincent Tao.

A Poem by Carrie Oeding

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Ways to Keep Self-Portraiting

I assembled a me from them, I assembled a you.

We know all the lines. I’ve drawn the negative space around each one.

I can’t draw myself because I can’t fit on the paper.

Someone said I look like Kiefer Sutherland and all of the Midwestern plains. Nobody can decide where the Midwest ends.

But what is the line for you are not alone, not at all said like we’ve said it before?

Like when we’re just saying anything instead of just saying anything.

I am an artist who has drawn every inch of herself except for what she looks like.

One day we will not know Kiefer Sutherland! My portraits will just evoke chipmunk cheeks. You say only chipmunk cheeks will remain. As chipmunk cheeks!

I have made nothing but what’s identifiable.

I made a mold of myself and cast several me’s. In soap, in disco balls, in a chessboard set. I poured in the entire state of Iowa, which you point out is clearly Midwestern.

I meet myself in cheese, and just want crackers.

Are you sure you want to eat that?

I have taken that line. I have collected all the tones —

Nice haircut. I mean, nice try.

That’s something different. I’ve seen it before.

You look like I used to, like when I was staying indoors.

It was a tremendous time! Those pants should go nowhere.

How would you make a sculpture out of Tell me something I don’t know?

The line you say as saying something still unsaid —

What kind of portrait would look like that?

I’d like to make a self-portrait you’d prefer.

A breaking bust,

something you can keep pushing off the pedestal display?

Self portrait as It once had a striking resemblance! It once had a striking resemblance! It once had a striking resemblance!

Carrie Oeding’s first book of poems is Our List of Solutions. Her work has appeared in Denver Quarterly, Colorado Review, Third Coast, Best New Poets, PBS News Hour’s Art Beat, and elsewhere. She is an Assistant Professor of English and Creative Writing at Marshall University in Huntington, WV.

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

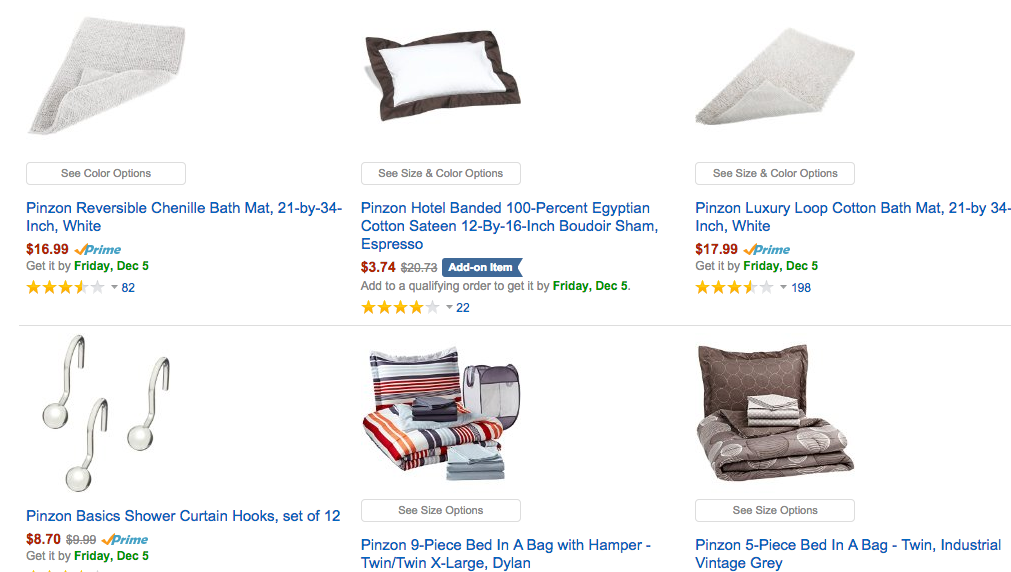

A Preview of the Real Amazon Store

Is Amazon good enough for your baby’s ass?

Called Amazon Elements, the diapers and baby wipes will only be available to customers who belong to the Amazon Prime membership program, adding another item to the growing list of membership perks. By working directly with a manufacturer, Amazon will be able to price the brand aggressively, with a 40-count package of diapers starting at $7.99. That works out to about 19 cents a diaper, compared to competitor prices that mostly range from 24 cents to 34 cents.

This will sound strange to people who don’t live as nodes in Amazon’s worldwide logistics experiment, but a little less strange to Prime members who do: Amazon already makes, or at least brands, a wide and strange assortment of things. Diapers are just one of its first attempts to move from things into the lucrative market for stuff.

Amazon’s feints at physical retail are focused on Kindles, tablets and phones: These are the tier-one Amazon products, in terms of visibility. They’re thing things Amazon makes to compete with Apple and Google. They get their own advertising campaigns, they’re purported to be in some way “innovative,” etc.

Tier two is made of products that are adjacent to the tier-one products. They’re electronics, or electronics accessories, that don’t really get much advertising, unless you count how easily they’re discovered when shopping Amazon for other stuff. These are the best-known of the “Amazon Basics” products. They’re HDMI cables and adapters. They’re cheap things, things that only have to function, usually in a single way, to be satisfactory; they’re also, perhaps not coincidentally, things that physical electronics stores, which Amazon would like to destroy, tend to mark up.

Tier two has grown out in some strange directions recently, which don’t make much sense from a storefront perspective but make plenty of sense if you can just imagine a spreadsheet: one column is a list of things that are relatively easy to have manufactured, and that people are purchasing a lot; the other is a list of things that Amazon’s competitors sell with decent margins. The rest of the “Amazon Basics” are things present in both columns (there are over 250 “Basics” products already). They’re adequate, brandless, government-cheese versions of things that are normally branded and fairly expensive: Jambox-style Bluetooth speakers, Beats-ish headphones, computer mice, game controllers. They’re bets, and pretty good ones, that their categories are, or are about to become, commodities — areas that other companies might be looking to get out of, because the profit margins are about to drop.

I’m not sure where to draw the boundary for tier three, which, again, seems to have been curated by some sort of ruthless retail algorithm. It starts with some of the weirder “Basics” and fans out. There are hangers and backpacks and… patio heaters? Folding fire pits? (Sample review: “Another nice feature of this fire pit is the cooking grate. We’ve had a few fire pits in our time and none of them have come with a cooking grate.” So, it’s a grill?) Paper and credit card shredders?

Some things that Amazon has that I was not aware of until today: A towel line. A pillow line. A patio furniture line.

Taken together, these products adhere to no particular aesthetic or theme — a house filled only with Amazon-brand products would look and feel like prefab model home. Again, since this is Amazon, the explanation is probably data. Not data about what people want, exactly, but data that suits Amazon’s goals: these must be relatively popular and relatively expensive product categories where brand loyalty isn’t too strong, and where Amazon can find cheap manufacturing partners. It’s a logistics partner looking at its suppliers and saying, dozens of times, “how hard could that be?”

Which brings us back to the diapers. Will people buy these? Maybe! Obligatory disposable turd bags are a good candidate, at least on paper. But people may turn out to be more precious about their baby’s poop-catchers than Amazon expects. What’s more interesting is to imagine where this comes next, as Amazon gets into what it calls “consumables.” The company already has a program called Prime Pantry, which encourages you to ship massive crates of grocery basics on a recurring basis — the types of things you don’t so much shop for as just buy. The products are all outside brands for now, but what better place to start slipping in house brands? FreshDirect already does this! Imagine:

— Amazon ketchup

— Amazon toilet paper

— Amazon condoms

— Amazon soap

— Amazon pasta

— Amazon beans, rice, flour, sugar, etc

Meanwhile, the company might try Amazon JEANS or TSHIRTS or at least socks or stockings or something. Why not? Amazon staples, sold via Prime, to ensure — as is the goal of its in-house electronics and accessories — not profit or even loyalty, exactly, but momentum above all.

New York City, December 2, 2014

★ Scraps of color hung in the morning sky, then were replaced with a well art-directed assortment of grays. The wind was seething. Rain fell, lightly enough to be tolerable. Little droplets floated against the black paint of the fire escape. Carrying an umbrella had seemed wise; one should always be prepared. But this was nothing an umbrella could help with. Cold drizzle fell in the evening. A woman in a short fur jacket, holding a gold clutch purse, gave up on her Metrocard and crept under the turnstile.

Here

by Bijan Stephen

She’d once written a book, Google said. This was a more than year ago now, while I was composing our eighth email, before I knew much of anything about Lindsey save for her name. That book is titled Here; as she’d have it (email #9), it’s a memoiristic compendium of essays that relives a brief sojourn in Austin, Texas. The book opens with a section titled “Do You?”, a series of rhetorical questions posed to her then-boyfriend — I don’t know if he ever read it. In the end, though, her questions echoed what we hid in our words to each other. Do you know what you need from me? Do you?

I was housesitting for my friend Cam, who’d left Connecticut for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for a philosophy course in logic. I was doing him a favor, and, besides, I had nowhere else to go: I’d just graduated, and this was the last safely indolent summer of my life. I wanted to spend what little I had on things that would reliably please me. It was hot then; I wrote for my beer money.

The beginning of that summer was lonely, as nearly everyone I knew had left for cooler climes. And so, like many others, I turned to the Internet for companionship.

I met Lindsey on Reddit’s personals section after I responded to her ad. It’s a weird place to meet someone — as Reddit is, for the most part, a home for the 18-to-25-year-old white male id — because it’s fundamentally a forum, an heir to those first message boards from the ’90s. Like its predecessors, Reddit still carries the same stigma: It’s a heuristic device for all the things that could happen to you on the internet, both good and bad.

I went there that day because it was removed enough from my fleshy, tangible life to feel safe. I don’t remember exactly what she’d written, or what she said she was after; we both used pseudonymous, transient accounts, and though our posts probably still live there somewhere, I’ve long since forgotten my username and lost my password.

Here’s what I remember: Lindsey was 26 and searching for someone to talk to, for easy friendship while she was bedridden at home in Arizona, squashed between her two dogs and her overbearing (doting?) family. For months we conducted some semblance of a relationship. We emailed, gchatted, and even sexted, a gradual escalation that happened over a few weeks. We were honest, raw with each other. We never met in person; there was never really a chance that we ever would.

I don’t think the intimacy we cultivated was false, but I also don’t think it could have survived a face-to-face meeting. It felt safe to tell her the things I’d hardly mentioned to anyone else — even people I trusted and whom I’d known for years — because the stakes felt lower.

Now, even though there are plenty of apps made to mediate or remedy loneliness, there’s still a sort of taboo surrounding the idea that an entirely digital relationship can fulfill emotional needs — that it can be anything more than a means to an end. After all, isn’t the easy intimacy between good friends worth more than its mediated equivalent?

I used to think so; these days I’m not so sure, or at least not sure how. For me and Lindsey, our relationship played out over thousands of miles and carried as much weight as I’ve ever felt. I told my friends about her. She told me about her poverty and her ex-boyfriends and her time as a sex worker — and, I won’t lie, I wondered where I’d fit in with the horde of them, where I’d fit in, theoretically, with her. We’d found a version of the couple-form that worked for us; it wasn’t anonymous or shameful, and the physical distance was more safeguard than impediment.

As it happens, I never got to answer that question. Lindsey and I lost touch after a few months, like our earlier escalation in reverse. I suspect it’s because we both got what we needed; there was a limit on us. Who’s to say things would have lasted any longer in person?

The other reason, I guess, was that I found it easy to simply let things fade. I’d started a new job in New York. My summer was over, and the leaves and temperatures had both begun to fall. I fell in with new people, some of whom I’d known in school and others I’d only known online.

That latter group I met mostly through Twitter — they were writers and illustrators and editors and book publishers and publicists. We knew each other only through what we wrote in our little room in that global salon. Now I’ve met them in person, and so I’m not left wondering what it might be like to share a drink, a meal, a photo, or a memory.

That’s not to say that a physical meeting is a higher form of communication. But it carries an undercurrent, an electric charge of possibility — which, I suppose, isn’t unlike the promise of an unopened message. The difference is immediacy, in what can be safely ignored.

It’s clear I wasn’t in love with Lindsey. It’s also clear to me that I didn’t really know her — though I’m not so sure that’s because we never viscerally connected. We were virtual but personal, digital and not anonymous, sexual, yet never physical.

Whatever the case, I’ve shared our little phrase with everyone who’s come after her: The brrring of a phone; the bzzzz of a text; the quiet ding of an email. They’ve always signaled something larger than themselves.

I read Here in a day or so, and this is how the story ends. In the last section, “Do You Still?”, the last line is, possibly, what you might have come to expect. “What do you want from me?” the book — Lindsey — asks. It may as well read “How well do you know me now?” These are the questions we have to answer for our every relationship, no matter where they’ve begun.