Caftan Lyfe

by Rachel Syme

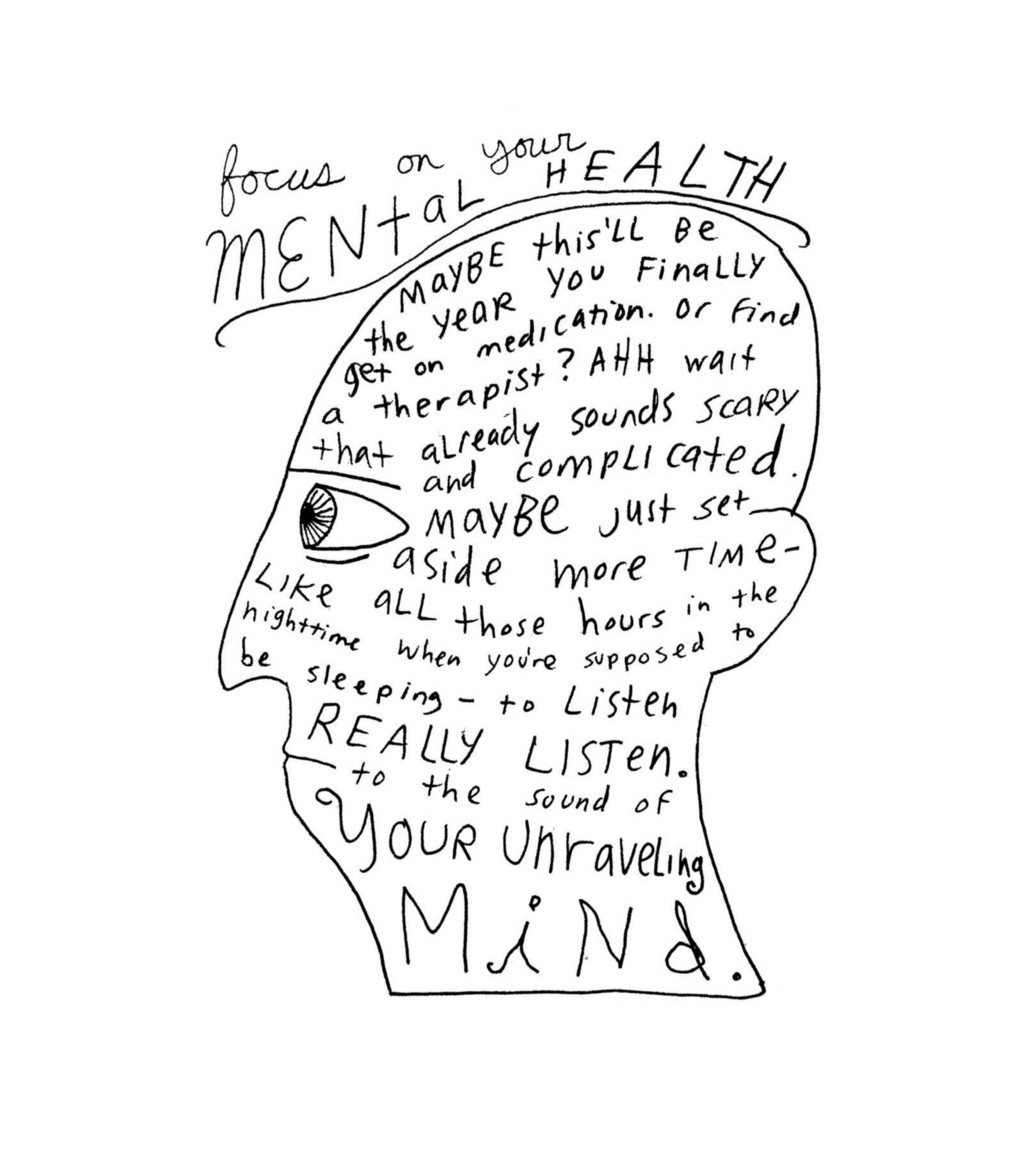

In January of 2014, I was still going to therapy once a week. My kindly therapist — let’s call him Ira, because when you picture an Ira, that’s exactly what he looks like — held court in a shabby ten-by-ten room with water-stained brown checkerboard carpeting at the base of the Dakota, on the corner of Central Park and 72nd Street. There was something thrilling about being cognitively deconstructed inside a landmark building on the Upper West Side that had seen so much action from the famous and the deranged. If Manhattan is the Epcot Center of neuroses, then my therapist’s location felt like Spaceship Earth, and I figured that being in such hallowed halls might be enough to clear the fuzz from my brain.

I started seeing Ira the year before to deal with the dual blows of heartbreak and writer’s block (one searing and raw, the other numb and grey) and since we had started talking, the pain had subsided and the words had come. I began to invent problems just to have something to discuss, which amused me for a while, but then started to feel like the law of attraction working in reverse. I’d tell Ira I had issues with my mother (who doesn’t, but my mother is regularly wonderful), and then suddenly I’d be bawling on my next call home, asking why she let me quit tap class when I was seven, why would you let a kid make that kind of decision, MOM. Or I’d say, “Ira, the deal is I need to lose ten pounds, that’s really the barrier between me and bliss!” Then for the rest of the day I would eat half a summer roll and six black iced coffees and analyze my reflection in every shop window for long minutes.

Ira was a good listener but not a good talker — the only thing I ever knew about his personal life was that he took a fishing trip by himself to Alaska every year and returned with a cooler full of vacuum-packed Coho salmon, which he would hand out to clients if they had a breakthrough. I still have two filets in my freezer. Still, I kept traipsing uptown because of that building, and how calm I felt during the seven-minute shuffle from Zabar’s; my long walks after my sessions became more therapeutic than any talk with Ira. I’d go to the museum and stare at the calcified nautili then head to Fairway to get three perfect clementines and devour them overlooking the West Side Highway, a few blocks away from the apartment where my great-grandfather lived when he defended the Rosenbergs at trial. I walked on every pathway Central Park has, and sometimes I made my own. But in January, I went walking west on 72nd Street and found something new.

I had passed the Off Broadway Boutique a few times before and always marveled at the windows — spangles everywhere, jaunty leather fedoras, cashmere wraps that could engulf a giantess — but had never gone inside. On the day I finally went in, it was bitterly cold. A bell tinkled, and right away I met shopkeepers Lynn and Pat, who were both wearing sequined berets and convincing an elderly woman that she absolutely needed a zebra-print pantsuit to carry on. I ran my hands along everything — silk boleros, gold brogues, brooches the size of baseballs — but my heart stopped when I saw a black caftan hanging by itself in a corner. It was beautiful: huge, diaphanous, almost obscenely sparkly, with gold beading that ran down the neck and the sides. I knew before trying it on that I would buy it, and I knew before buying it that I would buy ten more like it right away. I slipped it on and walked out of the dressing room to coos from all three women, who told me I looked like a queen. I swanned around the store like a demented Ziegfeld girl. The woman in zebra told me that if I didn’t buy it I’d be “dumb as rocks.” Pat told me “you’re not dressing for the grave.” So I bought it and took it home. Then my real therapy began.

I was not the only person to discover caftans in 2014. They are having a moment; they will have a bigger one in 2015, because many of the designer revivals are coming in the Spring collections, and by the transitive crap-to-table property of fast fashion, knockoff versions will start to pop up in stores later in the summer. Lena Dunham designed a capsule collection of caftans that will be ready to go in April. Jared Leto is wearing them on tour. Christina Hendricks, patron saint of buxom glamour, said that her favorite thing to do is go to Palm Springs with her best friends and have a “caftans and casserole” party. She wore one on the Tonight Show, and Jimmy Fallon wore one too. Mallory Ortberg got one. Jeffrey Tambor wore them constantly on Transparent; they gave Maura the power to become her full self. The Cut parodied the classic bikini-body women’s mag garb with a guide to getting a caftan body, which includes throwing out your razor and bra and letting crumbs fall where they may.

Generally, as many have said and will say until next year is inevitably horrifying, 2014 was the worst. Most people I know vacillated between anxious, catatonic, disappointed, anesthetized, angry, and then back around again in a kind of Sisyphean loop. But here’s what was good: putting on a caftan. Let me tell you about what happens when you put one on: you change. The caftan is a genderless, borderless, timeless garment. It has been worn by men and women for thousands of years — by the berbers in Morocco, by the rulers of the Ottoman Empire, by Russian peasants, by British queens, by Jewish princesses (both of old Hebraic and modern Long Island origin), by West African leaders and Haight hippies and movie stars. When you put one on, you melt into this history. You step out of time. The anxiety of 2014 feels like it exists on a continuum; the man or woman who wore this beautiful, body-swallowing masterpiece before you probably felt just as unsure of the future, but look, the caftan made it. You can make it too.

After I bought my first indulgent caftan, I got smart about my addiction and turned to Etsy, where twenty-something Kansans with vintage shops can’t give the things away in the Midwest, so their online offerings are stocked with flowing seventies global fabrics. I also started to buy from online estate sales from Florida or any other tropical climate where aging Jews go for their final canasta games. I went to Los Angeles in February for a few weeks and came back with an extra suitcase full from secondhand stores in Laurel Canyon. By the summer, which is high-caftan season, I had almost twenty-five. By the end of the year, my stock has doubled. I’m not ashamed. This is the best thing I have ever done.

Some things that are better in a caftan: Writing (but not tweets). Eating gelato. Making long distance phone calls. Cooking a curry. Reading. Listening to Nina Simone. Listening to Nancy Sinatra. Watching documentaries. Watching House Hunters International. Putting on eyeliner. Talking about world affairs. Making deals. Dusting. Drinking bourbon. Hosting a party. Air travel. Book browsing. Dancing. Foreplay. Walking through the desert. Walking along the ocean. Walking through New York City. Pretty much anything.

Caftans are not flattering. I barely clear five feet; I am not the type of person who should be wearing a mountain of fabric that eats me like Audrey II. I know this. But the point of caftans is not to hug the body; it’s to let you experiment with your own freedom, to do whatever the fuck you want under there. You will always look special in a caftan, and you will always look great. You will become comfortable with standing out in a room and realize that this is what you were born to do. Caftans turn ordinary people into peacocks, and peacocks into incandescent beacons. Do you want to be one of those? It’s possible.

Crying in a caftan doesn’t really happen, and if it does, it doesn’t last for too long. Caftans demand that you slow down, feel the billowing of the silk in the wind, practice moving meditation. The news kind of seems to float above you when you are in one — things are bad, but here you are, swaddled in cerulean paisley from neck to feet, and things could be worse. It’s not that caftans make you immune, but they do make you wistful. Caftans are always mentioned in tandem with utopia — why don’t we just move upstate and start a feminist commune where we wear caftans and drink good wine and THRIVE — and there is a reason for that. I really think if we were all wearing caftans this very moment we might not collectively feel so awful.

Get a caftan in 2015. The world will probably be the same, but you will have some armor. Don’t dress for the grave. Quit therapy. And if you need to go to the Upper West Side, go to Off Broadway. What you’ll get there is a lot better than frozen salmon.

Photo by Lorianne DiSabato

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

I Love You

by Mat Honan

I love you. Say it with me. I love you. Look me in the eyes and we will say it together.

I love you and have always loved you and will always love you, wholly and completely, with a completeness that is only possible because of your complete love, which completes me, as a person.

Sometimes, I will notice the way you make a little popping noise with your mouth when you smoke, as the cigarette leaves your lips. Are you not aware of this? How can you not be aware of this? You do it again and again (and again) with every drag, from every cigarette. You should stop drawing on the thing before you take it out of your mouth. Given how much you smoke, I can’t believe you haven’t noticed this yourself, I mean, Jesus, it’s really fucking annoying.

Still, I love you, all the same. That is how very much I love you.

But while we are at it, I can’t believe how much you smoke. Who still smokes? It’s disgusting, and it makes other people think you are disgusting, because of the way you smell. They might even be disgusted by me, at the thought of me kissing you. I hope not. But it’s why I always brush my teeth after we kiss. (I also wish you would take better care of your gums, but that is a discussion for another time.) Anyway, I wish you would at least think about swapping to e-cigarettes. I know it is not really your fault. You are an addict.

And so I love you, even if I don’t love your addictions. (You need to do something about how much you drink. It’s not cute or amusing anymore. You have a problem.)

But your problems are our problems, because I love you, and I can shoulder your problems and bear them with you. I am strong, and wise, and perfect in most ways. I have a twenty-eight-inch waist. I love the way your fingers fit perfectly in the creases of my abs, my sweet buttery love. Do you remember how thin you were when we met? When we fell in love? Oh! I do! What happened?

I would tell you to come running with me, but you are excruciatingly slow, and lazy.

Love will never die. Love will never die. My love will devour you, I will consume you, I will shit out your soul. I will take us to a dark place. We will go there together. Love. Love. Love. Love.

Photo by Thomas

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

All in My Head

by Jane Hu

This fall I made what is almost a comically bad economic decision: I started a PhD program in English Literature. Leaving my home of seven years in Montreal, I moved to California and, by the end of September, was watching Twin Peaks in a seminar with Linda Williams. It was a class on serial television, and though Linda posed the question as to whether TV studies had a chip on its shoulders, we largely proceeded from the assumption that TV ought to be taken seriously. This mental negotiation of approaching one’s scholarship with just the proper amount of self-ridicule isn’t singular to graduate seminars on TV, it turns out, as I found myself at various moments in those early weeks asking just what exactly it was I was doing with my life. You know, really doing.

¯_(ツ)_/¯

In all these ways, my semester began predictably.

Like a gentle hazing ritual, older students warned the first years about the job market — but always in terms of making light of the whole sordid situation. On top of the potential parochialism of scholarship, after all, there was the added threat that a decade of pursuing it might still not earn a living wage. Pretty funny, but definitely funnier for the self-aware! Were we all doomed to be punch lines of a very tired joke? In which no one got a job? But the true comedy of grad school perhaps is that its beats are more uneven than that — you often can’t anticipate when one is coming. Because no matter what anyone says, academia does not occur in a bubble. Life happens.

(╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻

A little more than a month into this first semester, my head broke. I fell off a bike, helmetless, and split my right temple on the edge of a curb. The cut missed my eye by an inch, though at the time — sitting concussed and slightly bloody in the street — I was largely focused on locating my glasses, grateful to find them intact. It did not occur to me then that, had I fallen a little less to the side of my face, I might have cut the lenses; or they might have cut me. The details between the ambulance ride to ER and the IVs that leave my arm still bruised are ultimately boring. I’m pretty sure it hurt? When my roommate drove me home from the hospital, I managed to get all the vomit inside a Whole Foods bag, apologizing between burps. I’m pretty sure it was funny.

The following days were sheer slapstick. No longer able to write the essay due that week, I instead found myself returning to the hospital for a CAT scan. (“It hurts to move my eyes,” I told my doctor over the phone, upon which she immediately asked me back. My initial vital signs were so good that this new development seemed cause for alarm.) Her first sentence after the results came in were “You surprised me” — words you never really want to hear from your doctor. The x-ray revealed shattered bones, as tiny fractures surrounded my right eye and collapsed the bone from which one’s jaw muscles hang. “How much pain were you really in that day?” my doctor’s now a source of cheering validation. “You’re a tough cookie.” (A cruel metaphor, given the scan!)

Next came surgery; then more drugs, more stitches, some more pain, a lot more jokes. There were entire days where I lost hold of the fact that I was in California for grad school. At the same time, I was never more aware of how contingent school was upon my recovering. My ER doctor informed me in gentle tones that my face would bear a permanent scar, and my surgeon warned me about the risks of nerve loss, but the scariest thing anyone said to me was by my initial discharge nurse, who explained how internal bleeding in the head and around the brain can occur in weird pressurized ways, slowly and over time. “If anything seems off over the next few days,” he said, “come back to the ER immediately.” Funny instructions, but you get what he meant.

(⊙ω⊙)

In Eve Sedgwick’s remarkable essay about paranoid reading, she explains that “the first imperative of paranoia is There must be no bad surprises.” She continues: “because there must be no bad surprises, and because learning of the possibility of a bad surprise would itself constitute a bad surprise, paranoia requires that bad news be always already known.” As I kept finding myself in waiting rooms, anticipating yet another turn of the screw, I wondered whether paranoia demanded that “there must be no bad surprises,” or whether it was simply the case that most surprises are bad, paranoid or not.

Aware of the implications of Getting a PhD In This Economy (thank you cautionary think pieces!), how could I have truly prepared for the degree? And even if I could have, no one ever factors in the probability of something like a head injury. “Guess what,” writes Sedgwick at one point, “you can never be paranoid enough.” Here, Sedgwick is being half-facetious, channeling the words of another critic, D.A. Miller, but at the time of my unraveling accident, I read that line in new light: guess what, you can never be prepared enough. An apt sentiment for 2014 too, perhaps.

╮ (. ❛ ᴗ ❛.) ╭

A friend who had been counseling me through my academic hesitations made, upon hearing about the accident, a seamless observation: “The psychoanalytic obviousness of getting a violent head injury during your first term of a PhD program is no compensation. Being hit over the head with etc. I wish you’d been given a helmet, in multiple ways.” She was right, of course, though over the following months, I learned to turn the accident into another form of compensation. School had already been confounding enough; my head injury seemed only the natural externalization of that. Instead of “grad school is weird because I’m all wrong,” I could now say “grad school is weird because I fell on my head!” In ways, the injury became a source of relief. Don’t understand what you’re reading? Blame it on the concussion. Too nauseous to attend class? Concussion! I mean, maybe it was all in my head.

Perhaps the most terrifying aspect of these justifications was just how little a difference there might seem between a real concussion and a fake one — how, though it might be reassuring to have a concrete reason for intellectual deficiencies, one can never be entirely sure how to diagnose failures of understanding. Just because you’re concussed doesn’t mean that something might just be difficult in its own right. You can never be paranoid enough.

( ᵒᴥᵒ)

But Sedgwick’s theory is more complex that, and takes into account paranoia’s flip side: reparative reading or, in other words, the possibility of good surprises.

Because there can be terrible surprises, however, there can also be good ones. Hope, often a fracturing, even a traumatic thing to experience, is among the energies by which the reparatively positioned reader tries to organize the fragments and part-objects she encounters or creates. Because the reader has room to realize that the future may be different from the present, it is also possible for her to entertain such profoundly painful, profoundly relieving, ethically crucial possibilities as that the past, in turn, could have happened differently from the way it actually did.

(Can you imagine 2014 happening any other way than it did? Should you?)

The dogged, defensive narrative stiffness of a paranoid temporality, after all, in which yesterday can’t be allowed to have differed from today and tomorrow must be even more so, takes its shape from a generational narrative that’s characterized by a distinctly Oedipal regularity and repetitiveness: it happened to my father’s father, it happened to my father, it is happening to me, it will happen to my son, and it will happen to my son’s son. But isn’t it a feature of queer possibility — only a contingent feature, but a real one, and one that in turn strengthens the force of contingency itself — that our generational relations don’t always proceed in this lockstep?

Sedgwick wrote this essay in 1997, which isn’t that long ago when you consider all the consistently terrible years that have occurred between then and now, not to mention those that preceded it. But to take such a view is always to read as a paranoiac — to try to be paranoid or prepared enough, rather than attempting to realize a different outcome entirely. Hope is fracturing, sure, but as Sedgwick reminds us, it remains crucial.

☆.。.:*・°☆.。.:*・°☆.。.:*・°☆.。.:*・°☆

Photo by Julian Bleecker

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

Never Better Enough

by Casey N. Cep

He never got better. Well, not quite: He got a little better, but then he got worse. He never got better enough.

When my uncle died in November, it was after years of sickness and suffering, but also years of health and joy. You’ll forgive me for sometimes forgetting that he was dying. Daily life isn’t orderly; it’s chaotic, so even when someone is dying, you sometimes forget.

Was he dying when he sat teasing my cats with a laser pointer, telling me a story I’d never heard about the time some friend of his had fed their cat peyote and she raced around the house like a demon? He didn’t seem to be. He didn’t even seem to be dying in his final weeks, when he would sit quietly on my couch, opening his eyes only to tell me that he was meditating, a thing I never knew he did, but that he explained he’d learned once in a yoga class, something I would never have believed if he had not been telling me about it so seriously.

When exactly did my uncle begin dying? It’s not as fixed a moment as when he died. That happened one cold November night: his life a tall glass from which he took big swigs for six decades until finally, after a few last little sips, the glass was empty. I know precisely when he stopped drinking, but not when the glass went from being more full to being more empty.

One of the most haunting phrases I learned as a hospital chaplain was “actively dying.” The patient is actively dying, the nurses might say when they called for a chaplain, meaning you’d better come quickly. Often they were right, but once a patient said to be actively dying went home a few weeks later and a few months after that I went to his fortieth wedding anniversary.

A novelist can pull a plot out of death, but for most of us death comes and goes, drawing frighteningly near and then going blissfully far away. We rarely know how closely death is stalking us. A child might wonder if death had been hiding in the pockets of my uncle’s flannel shirt or between the matches in his pocket, but an adult worries about where death will go next.

The longer we live, the more we worry about how soon we’ll die. This year had even more talk than most about immortality and even more research into senescence. It’s not enough to stall the aging process, we want to stop it. Even Google is trying to turn us into Tithonus. Would living forever be better? I doubt it. Our life expectancies already lengthen like shadows, bringing their own kinds of cold and darkness. We may have cured many of the diseases that killed our grandparents, but illness has found new forms.

2014 was my uncle’s last year. Was it better than the ones that came before? I doubt it. His life was full of good years. The year he met the girl he almost married; even the year she moved back to Florida with her family and he stayed in Maryland with his. The year he cut his hippie hair to join the Army; especially the year he finished his service and started to grow it out again. The year he got a new red Firebird; even the year he lost his license and my grandmother started to race around town in it. The year he inherited a grey parrot from my great uncle who was so loud we children covered our ears when he squawked but was so sweet he would sit on my great aunt’s shoulder and try to pull out her false teeth. My uncle’s life was full of good years; 2014 was just his last.

Photo by Judy van der Velden

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

From Davis

by Bijan Stephen

I was a dreamy kid, one who never really understood how the world worked: I always had my head in a book, was always trying to learn the way things were without ever facing them directly. Between my father’s medical journals and my Piers Anthony novels, I remember thinking I’d acquired a useful working knowledge.

I grew up in East Texas; last week, after 21 years, my family moved to Davis, CA. I arrived only days ago, but I already know how the days dawn around here: Sometimes misty, always silently. The rest is unfamiliar — the house, the town, the faces. It’s not a bad place to reflect on the year, far away from everything I’ve known.

My childhood never seemed real until I left for good and realized it was a large part of my identity. This is probably the result of never quite believing that I had to live in a place where race had anything to do with me.

2014 was the year black death finally made it back into the mainstream conversation. People are starting to realize our vaunted post-racial nation is still, in fact, stuck in the 60s — that, in so many ways, we haven’t moved meaningfully forward. If anything seems new, you haven’t been paying attention.

2014 was also the year I broke my promise to myself and started writing about race. To be a beat reporter for your own skin is exhausting, and vaguely humiliating. As Cord Jefferson put it:

When beginning any career, it’s important to highlight the experiences and skills you bring to the table that others can’t. For some marginalized writers, that means being direct about the fact that your personal perspective as a woman or homosexual or African American — or all three — will occasionally be perceived as refreshing in an industry so dominated by straight white men.

It’s a slippery slope, I told myself. If you start you’ll feel obligated to say yes to the assignments and editors that start turning up. Remember there’s a price: You give part of yourself in return for publication. Make sure you get enough.

This year — the year of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, of uncountable smaller indignities, of many thousands still gone — wasn’t really different than any from the decade before it, or from the ones before that. We’re still wrestling with the same issues. Progress came in the form of imperfect salves, too little and too late.

For me, 2014 was the year I was most aware of the world, in ways my younger self couldn’t have conceived. That there would be a firehose of news, an irresistible torrent of information, and that I would be a part of the cycle, was (and, for me, still sort of is) beyond imagining. I know a little bit more now, and I realize that in this moment, right here, right now, I am alive and living and things are real. I realize that this experience isn’t fake, and nobody’s behind the curtain. No one’s off-screen pulling strings.

I guess what I’m trying to say is I’ve realized that nothing has changed but us — nothing but you, nothing but me. If history is an emergent property of randomly mixed groups of people, then 2014 was part of it and 2015 will be, too. I’m not sure yet where hope fits in.

It’s nighttime in Davis. I don’t yet know what it’s like after the sunset.

Photo by Robert Baker

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

Arm Wrestling With a Gorilla

by Natasha Vargas-Cooper

You found the gorilla, with its flinty human eyes and fatherly fists, to be intriguing. You would slip into its cage at night, after work, and you would arm wrestle. Your dad taught you some tricks that bested the gorilla.

The matches would go on longer than you wanted. We learned that it’s only over when the gorilla wants it to be.

I tried to coax the gorilla away with money.

Then I offered you money to fight off the gorilla harder.

Then I tried to reason with the gorilla but he simply turned his saddled sloped back to me. I pulled out tufts of his coarse silver hair with my fists but he only snorted and brushed a translucent louse from his foot.

Then I thought maybe if I encouraged you, you’d beat the gorilla. I demanded you go to lessons, training, a crossfit gym on Venice Blvd.

You went a few times then never again. You didn’t like the people. They tamed lions. Boxed rhinos. Kickboxed panthers. What did they know about arm wrestling with gorillas?

When you were hurt after the wrestling matches, I would scold you because I thought it would convince you to stop.

Other times I’d put my lips to hottest part of your green bruise and I’d tell you I would never leave until you killed that goddamned gorilla.

But there were nights, when the tricks your father taught you failed, that I rooted for the gorilla to obliterate you.

At some point, you were living full time with the gorilla.

I started vacuuming the cage.

Providing delicious snacks for the three of us to so we could all live in peace.

I bought a couch from West Elm to cheer the place up.

You and the gorilla became drinking buddies, singing Steve Miller songs and chucking rocks into the koala’s nests during the day. Then you would weep together, muffling your sobs into each other’s big shoulders. Sometimes the three of us would stay up late watching old movies and grooming each other.

But this made your arm wrestling matches more explosive, edged with the sentimentality and anguish that only brothers feel.

Sometimes when the gorilla was asleep, you would wake me up to arm wrestle.

We both drew blood. When my wrist was too sore and sprained I would sneak out of the cage to admire the giraffes with their grandmotherly eyelashes, and dumb, elliptical chewing. Their knobby legs balanced gently on the colonies of cord grass. I asked the giraffes if they knew how to beat a gorilla in arm wrestling. They did not answer but regarded me warmly with their black burning eyes.

I spent more time with giraffes and less time at the wrestling matches. Our couch was ruined and the cage had grown filthy from my lack of sweeping. You said you were angry, you could not beat the gorilla without me.

I stopped going to arm wrestling matches. I told the giraffes who I thought was winning. I was rooting for you. Who were they rooting for, I asked? They only lowered their colossal necks swirl their purple tongues in the shallow pools of water. I told them how I wanted to vacuum the cage and if they had any housekeeping tips but they just craned their strange faces up towards the sun.

One day I did not come back to the cage. I have bought a new couch and I sleep on it alone with my feet outside the blanket like I always do. I hope you won. Please find me when you do.

Photo by Willard

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

New York City, December 29, 2014

★★★★ Someone’s track pants billowed like suiting in the moving air. Contrails made plaid of the blue sky. The cold was not deep enough to exact a penalty for walking out with hair still wet from the shower. The daylight seemed already more expansive, just a week past its minimum. A silvery, rimpled sheet of cloud caught the afternoon light in the west. Then the colored sunbeams broke free, tracing each railing post and vent pipe on the top of the new-built tower — and the puff of vapor from one of the pipes, the guts of the building having come alive at last. The sun had recovered its confidence. Pale pinks and purple-grays washed over the clouds, and then. And then: a flamingo-down pillow ripped violently open, exploding over the avenue. People stopped dead to snap pictures. Bits of hot magenta scattered all the way off to the north. After the sun had taken its colors below the horizon, its canvas was revealed to be a cloud formation so thin that the white moon, just fuller than half, shone straight through it.

1914: The Year in Review

by Mary Pilon

Over the holidays, while watching two children create Lego worlds at the foot of a glowing Christmas tree, it suddenly hit us that in only five years, it will be the twenties again. Feeling old, my cousin and I took swigs of white wine and shoved our faces with ham. So, instead of reflecting on 2014, let’s take a look at 1914:

— On June 28th, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, were shot and killed, triggering a cascade of violence. The “Great War” was disease-ridden, fought in ungodly trenches, saw the deaths and injuries of millions and set the stage for World War II.

— In August, president Woodrow Wilson’s wife, Ellen Axson Wilson, died of Bright’s disease. In reviewing 1914, I found that many stories conclude with Chekhovian despair over losses like Wilson’s. Death and disease permeated culture then in a way far beyond what most of us can comprehend today. The average death rate was 13.6 per 1,000, a record low at the time, but much worse than today’s 8.07, while life expectancy was 52 years for men and 56.8 years for women; Tom Cruise and Geena Davis would likely be dead, not still acting.

— On Lexington Avenue near 103rd St., a bomb intended for John D. Rockefeller exploded in an anarchist’s apartment. The incident became Known as the “Lexington Avenue bombing;” four people died and dozens were injured. It was one of many politically charged acts of violence of the time, among them bombings and assassination attempts by anarchist Luigi Galleani and his followers. Meanwhile, at Frank Lloyd Wright’s home in Wisconsin, an angered servant killed seven people, including Wright’s mistress and her two children, and torched the place. The “Wright-mare” was a national news sensation at the time, and became the stuff of architecture student lore.

— Against this backdrop, pop culture, as always, provided reflection. Radio was the rage, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ “Tarzan of the Apes” was published and Charlie Chaplin was on screen as the Little Tramp. Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” hit shelves. James Joyce’s “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” began episodic publication in London. E.M. Forster wrote a novel of homosexual love, Maurice, that wouldn’t be published until more than 50 years later.

— Charles Taze Russell, founder of what we know today as the Jehovah’s Witnesses, predicted October 2, 1914, as the date for the “full end” of Babylon. We’re still here. For now.

— Greyhound Lines was established in Minnesota as a bus transportation services for iron ore miners. It would be nearly a century before the Fung Wah lines would make Greyhound buses look posh in comparison.

— In August, the Panama Canal officially opened! An engineering marvel and the subject of much criticism, the canal would not be taken over by the Panamanian government until 1999. Its construction posed a variety of health risks to its workers, who battled mosquitos and malaria; many thousands died. Today, the canal still faces millions in cost overruns.

— The Gopher Gang had control of Hell’s Kitchen and corruption involving police and the mob proved a repeated issue, most visibly in 1914 with the dismissal of Chicago’s police captain. Crime was higher and payoffs to law enforcement were prevalent; in the South, Jim Crow laws reigned.

At least now we have the future to look forward to, and not a locust plague.

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.

The Legend of Avicii

by Jeb Boniakowski

A couple months ago I met up with a childhood friend for a drink. He was working as an assistant to a famous music producer, and one day the producer was doing some work with another Famous Artist whose name I’ve removed to make life harder for anyone who wants to make an investigative podcast about this rumor. Being one of the four assistants employed by the producer, he had a lot of time to chat with his opposite in the Famous Artist’s camp.

Famous Artist’s assistant had previously been Avicii’s assistant. As he told it, Avicii rang in 2014 by playing a midnight ball-drop set in Tokyo, then zipping to the airport with a police escort like a head-of-state’s motorcade, hopping on a private jet filled with cocaine and Dom Perignon, then flying to Paris to play another midnight set. After the Paris set, more police lights, different siren tones, more private jet, more cocaine, more champagne, and then he landed in New York, where his motorcade rushed him into a third club so that he could play a third midnight New Year’s Eve set. Third time handing his champagne glass to a waiting assistant. Third time splashing some cold water on his face in a marble club bathroom. Third time climbing, alone, the stairs up to the DJ booth.

This is my favorite story ever.

A lot of people I’ve told this story to say, “Ehhh, I don’t think that’s actually possible…is the time change on an ordinary private jet travelling at a velocity of six hundred…” or “but would the police really escort a DJ?” Shut up! We could all probably figure that out with Google but I don’t care. That’s not the point. This is a DJ story.

Let me share with you another Avicii story, this one from GQ:

Four days before New Year’s, I arrive in Playa del Carmen, Mexico, to find him pacing around a tented greenroom at Mamita’s Beach Club, smoking like a chimney and knocking back Red Bulls. The champagne is chilling. The waves are lapping gently at the shore. But [Avicii’s] attention is entirely focused on the sounds coming from the stage, where a warm-up DJ is playing a song called “Epic” by Dutch DJs Sandro Silva and Quintino. “I can’t believe he’s playing this,” he mutters. “This is really frustrating,” he says, grinding out his cigarette and lighting a new one. “Is he gonna play ‘Don’t You Worry Child’ next?”

Felix gives him a warning look and nods in my direction. Vin Diesel bald, with discernible muscle groups, Felix has all the indicia of scariness until he opens his mouth. (“I carry his drugs in my butt,” he later jokes when asked to describe his duties.)

…

“We should make a list of songs that we tell festival organizers not to let other DJs play,” [Avicii]’s tour manager, a no-nonsense Irishwoman named Ciara Davey, says decisively, as if writing a note to self. [Avicii] nods, though he doesn’t seem any less tense.

Look, I’m not a “disco sucks” guy. I love dance music. I love disco. I think Mick Jagger should probably be in that monster book that Dungeons & Dragons people use, but this is amazing. Two hundred and fifty thousand dollars a show! The modern EDM DJ is essentially the master of the Personal Brand.

Let’s say you walk into a Las Vegas nightclub and “Don’t You Worry Child” is playing. How would you know if Avicii was playing or a mere warm-up DJ? Or some guy’s iPod? There’s no crate-digging or curatorial skill at work here. “Don’t You Worry Child” entered the charts at #1 all over the world. This stupid song again? Inescapable in the great Cascade of content that inundates the world. But if you know that Avicii is the guy playing it — if you see his captain-of-the-enemy-team-in-a-sports-movie head bouncing over the glowing trading turret of the DJ booth — now I can feel our fun “Levels” rising!

A couple weeks ago the New York Times ran a story with the headline, “The Year of the Never-Ending Party” accompanied by a delightful 68-picture slide show. It’s about “the recent surge in entertainments.”

“That was just Monday. Any person of moderate social enterprise had the choice of at least five separate balls or galas every night for the rest of that week.”

I would like to think of myself as a socially enterprising bachelor and yet I wasn’t invited to a single ball or gala in all of 2014! Were you? Did I say something rude to the wrong Astor at the last Saratoga track season? Did I play a particular #1 single off Spotify just before a $250k-a-night DJ showed up?

“It’s more over-the-top,” [Interview columnist Bob] Colacello said of the recent surge of entertainments, five or more a night and in almost all five boroughs. “It’s uptown, downtown, Brooklyn,” he added, and even in the Bronx, if you count last week’s gala at the New York Botanical Garden. “It reminds me a bit of the ’80s, with big gowns, big jewelry, big money spent in restaurants,” he said. Now, as then, the Champagne rivers are flowing, and they are vintage French and not some California sparkling. The caviar mounded again in iced silver buckets is also imported. And, as Mr. Colacello said, “Now there are white truffles shaved over everything.”

Is there literally anything worse than being handed a flute of something bubbly cold and golden, taking a sip, and realizing it’s some California sparkling horse piss when you were expecting vintage French?

Even though they might not realize it, it is for these people that Continuous New Year’s Avicii exists. I sometimes wonder if this is how gods are made: First, a possibly-real person moves beyond folk hero to the in-between realm inhabited by people like Jack Frost, John Barleycorn or Big Oil, and then people forget where the story came from and improve it over the years and next thing you know you have a Santa Claus or a Baal who used his magical powers to keep free water-powered cars off the road and cursed Los Angeles to never have a real subway.

Avicii has all of the tools to be god of Those of Moderate Social Enterprise. The peak ritualized experience of New Year’s Eve is, of course, The Drop, and so New Year’s Eve is the ultimate feast day for EDM and its DJs. Avicii’s mission is to bring The Drop to the people. He has a fanciful mode of travel in his private jet and his motorcade. And he has the magical artifacts: bottomless bags of cocaine and Dom Perignon, his Mjöllnir and Gungnir. And, in a year when our collective dreams turned from Endless Summer to Permanent Midnight, he’s up there, one of the stars, streaming across the sky.

Photo by Steve Hall

Never Better, a collection of essays from writers we love, is The Awl’s goodbye to 2014.