New York City, January 22, 2015

★★★ Now the seasonable half-day’s allotment of pleasantness came in reverse: a dark morning’s clouds thinned and the light slowly intensified, till the afternoon sky was clear blue and the scaffold shadows sliced up the sidewalk. Up in the treetops, the sun was precise on the fine new buds; down by the river, it spread a vague, spectral shimmer over the water. An arc of dry pigeon droppings traced the arc of the awning around the back corner of a Trump building. Pink-rimmed purple clouds rode above the descending sun, which was round and just bright enough to leave a field of polka dots on the retinas after tempting the eye to follow it.

Magazine Taken to Slaughterhouse

“I don’t want to speak ill of the dying, but what is the plausible audience in such a magazine?” he asked. “It was too kind of nitty-gritty and old-fashioned, back-to-the-land hippie magazine for the food-farm porn market, and yet too ‘What about the dairy situation in the Philippines?’ for people who are really raising chickens for a living.”

Fortunately for Kurt Andersen’s karma, but not for anybody who worked there or is owed money by it, Modern Farmer, the National Magazine Award-winning publication about farming for people who have no actual interest in farming, is no longer dying, it is dead:

Jesse Hirsh, a senior editor who came from San Francisco to help start the magazine, and Cara Parks, the executive editor who joined the staff in October, were the paid editorial staff that remained. When they left Friday, the editorial content was left to two interns who were scheduled to leave by the end of January.

Will the last intern to leave the office please remember to feed the goats on the way out?

Thoughts Likely to Pop Into Your Head While Meditating at Davos

1. Fascinating conversation with Wim Drexler about how helicopters work. Terrific guy. Princeton.

2. Is my wife’s hair actually blonde?

3. I can’t tell if I really give a fuck about Greece or it’s just been going on so long I have convinced myself. Wait. If my wife’s hair isn’t actually blonde, is that less hot, or more hot?

4. Is it bad that during the Global Financial Council on the Global Financial System I kept thinking about how maybe we could just get rid of Cyprus?

5. Next person who tells me that the founder of Patagonia lives in a straw bale house gets a knuckle sandwich.

6. Brendan is wrong about my backhand. I feel like I should start working with Aislan. But what will I say to Sue? How will I get away with that? I know. I’ll say “Aislan’s got a more holistic approach.” Sue will love that.

7. I really hope Sue doesn’t want to watch Empire again when I get home. I just thought it very predictable.

8. If Matthieu Ricard spent five minutes working on the soybean and proteins desk he would shit himself.

9. God I’m really craving the Octopus with XO sauce and brown butter espuma from Tuome.

10. Or maybe just some cheese. Cheddar is so basic, but satisfying. At the end of the day, I really am down to earth. I like that about myself. I don’t think enough about the things I like about myself. That’s why I think Aislan will be good for me. It’s not about my backhand, it’s about my confidence.

11. Why didn’t I get into Princeton?

12. I am surprised at the number of men here wearing those little colored thread bracelets their daughter made them. I never even thought about that. Maybe they have really young wives and she sets the tone for a younger household. Sue is only six years younger than I am. How much younger does your wife have to be than you before you think it’s ok to wear those little uh…uhhhh.

13. I do care about Greece. I stand with them. And I don’t actually want anything to happen to Cyprus, that was just a fantasy. Oh my God, I’m actually crying.

14. Friendship bracelets. That’s what they’re called.

15. I have a deep attraction to Ali Larter that I can’t help but wish to explore.

16. The Renewable Energy dudes look like they get a lot of ass.

17. I opened my eyes and Matthieu Ricard’s face looked so calm and resplendent.

18. You can spot the journalists. They arrive by van from those hotels that look like where Hansel and Gretel went to middle school. I stayed in one of those my first year. And this year an elevator opens in my room. It has been a journey.

19. The words “Aislan” and “confidence” must never, ever be in the same sentence when talking to Sue.

20. Oh I got a text. No one’s looking what’s the big deal. Oh, it’s my daughter. Wow. Olivia never texts me. How wonderful! “Dad Hows the sausage fest lol”

Photo by WEF

Under Pressure

by Brendan O’Connor

One day at the end of August, dozens of cases of seltzer were piled in stacks that rose chest-high around a cramped warehouse in Canarsie, Brooklyn. Each case holds ten bottles of seltzer and weighs seventy pounds when the bottles are full. A small black cat slunk between the stacks. “That is Chicago,” Alex Gomberg, a twenty-seven-year-old, fourth-generation seltzer man, said. “If he bites you, I will chase him outta here.”

Alex’s great-grandfather, Mo Gomberg, a seltzer delivery man with his own route, had been filling up at a co-op in Brooklyn when he decided to open up his own shop, Gomberg Seltzer Works, on the corner of 92nd Street and Avenue D in 1953, so “he didn’t have to schlep it anymore,” Gomberg said. At the time, there were dozens of such filling stations in the city, hundreds of seltzer men, and thousands of customers receiving cases of seltzer at their homes every week. Mo passed the business to his son Pacey, and Pacey passed the business along to his son — Gomberg’s father — Kenny. Only two of Gomberg Seltzer Works’ four siphon machines, manufactured in London in 1910, are still operational, and only one is actually in use. “We’re the last fillers in all of New York,” Gomberg said. “People don’t know it, that it exists anymore.”

For a long time, seltzer was just a New York thing. Jewish immigrants brought a taste for seltzer — “the worker’s champagne,” as it was colloquially known — to the Lower East Side in the late nineteenth century. “In 1880 there were only two seltzer companies in New York,” writes historian Gerald Sorin in his book A Time for Building: The Third Migration, 1880–1920. “By 1907 over a hundred operated in the remarkable ethnic economy Jews had created.” When Canada Dry started marketing flavored seltzers around the country in the mid-eighties, “it found that few people outside the New York area even knew the word,” the New York Times reported in 1986. “The company had to include the phrase ‘sparkling water’ on packaging.”

Real seltzer is made like this: City tap water — commonly understood to be the reason for the quality of New York’s pizza and bagels, and which comes from a nearly two-thousand square-mile network of nineteen reservoirs and three “controlled” lakes that extend one-hundred-twenty-five miles north and west of the city — is triple-filtered through sand (to remove any solids), charcoal (to remove any odors or tastes), and then paper (to remove any remaining particles). Then it’s mixed with carbon dioxide in a very loud carbonator, where two beating paddles diffuse the gas into the liquid. Each bottle is placed into the machine upside down, by hand. Atop each is a head with a spout and a trigger mechanism. Inside the head, amongst a half a dozen other parts, is a valve — when the bottle is placed into the siphon machine, a lever presses a trigger on the side of the bottle’s head, which opens the valve, and the newly carbonated water is forced in. Each bottle, when it is full of seltzer, contains sixty pounds of pressure. Gomberg gestured with one. “If this thing falls down and explodes, you’re done. You’re gonna get hurt. It’s not pretty,” he said. “Sometimes you don’t see a crack in the bottle. We try to look at all the bottles and make sure, because if not?” He rolled his eyes and grimaced. “I should probably put mats down.”

The glass bottles, about three thousand in all, are a quarter-inch thick. The oldest were hand-blown in Czechoslovakia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and some are engraved with the last names of the delivery men to whom they belonged. “When there were hundreds and hundred of seltzer men on the route, everyone had their own bottles,” Gomberg said. (Customers typically don’t own the bottles; they just pay for the service and the seltzer inside, exchanging empty bottles for freshly filled ones during each delivery.) Recently, Gomberg found bottles belonging to the fathers of two of his customers. “Abisher and Singer — both fathers were seltzer men,” Gomberg told me. “It says ‘Singer and son’ on one and ‘Abisher’ on the other. I sold the bottle to them, but they keep giving it back to me so I can fill it. So it’s not like I’m losing it. I’m still making money off it.” He paused. “You know, people thank me. I’m like, ‘You don’t have to thank me, I’m trying to make money!’ But they say, ‘Thank you for keeping the business alive.’”

Seltzer bottling hasn’t been profitable as a business for a long time, and it shrinks every year. People die, or move to Florida. Gomberg’s father Kenny makes his money as a beer and soda wholesaler, operating out of the other side of the warehouse; he’s kept the filler machines running as a favor to the guys still on the route. “Don’t take this the wrong way, but these guys are eighty years old,” Gomberg said, waving towards a stack of cases. “He’s not gonna be here forever. Who’s he passing his route to? Where do you think his customers are gonna go when they can’t find seltzer?” he laughed. “None of these guys have websites. They’re pen and paper. I’m the first seltzer man with an email address!”

Gomberg and his three siblings grew up in New City, New York, about an hour upstate from the city. “We had seltzer at the dinner table all the time.” Now he lives in Fort Lee, New Jersey, with his wife. She drinks about a case a week. “She mixes it with everything,” he said. “She loves it. That’s why she married me.” But growing up, he never expected to carry on his father’s business. “I don’t think anybody is going to wake up one day and say, ‘I want to be a seltzer man.’ Who wants to carry a seventy-freakin’-pound case up different sets of stairs every day?” he asked. After two years at Rockland County Community College, Gomberg transferred to UMass-Amherst, where he pursued an M.A. in higher-education administration and advised club sports teams. After graduating, he couldn’t find a job he liked in a place that he liked, so he decided to enter the family business.

Initially, Gomberg only wanted to open an egg-cream stand at the Barclays Center, but he found the process to become a vendor at the arena to be too bureaucratic. “It was too involved logistically, too much money,” he said. Instead, he started his own delivery route. “We had all these bottles just sitting here doing nothing. So I cleaned ’em up, restored ’em. Started pounding the pavement.” A case of Brooklyn Seltzer Boys’ seltzer costs thirty-five dollars per delivery, with a hundred-dollar deposit for the bottles — at least three or four times as much as store-bought seltzer. “It’s cheaper, for sure,” Gomberg said. “Doesn’t taste as good, but it’s cheaper.” Part of the reason that Gomberg’s seltzer tastes better is because it remains under pressure. The “bite” that you feel when you take a sip of a carbonated beverage — not the tickle of the bubbles, but the slight bit of sharpness in the back of your throat — is proportional to the amount of gas in the liquid, and these bottles, with their century-old nozzles, keep the pressure contained. “Good seltzer should hurt,” reads the back of Brooklyn Seltzer Boys’ t-shirts, a phrase borrowed from Gomberg’s father.

Seltzer consumption is increasing in the United States, for the first time in a long time. When sales rose by 16.3 percent in 2011, this was greater growth than any other product on the bottled water market, according to an industry report published at the time by the Beverage Marketing Corporation. In 2012, Forbes reported that sales rose by a further thirty-four percent. According to Forbes, seltzer — or, well, “sparkling water,” really — accounted for around ten percent of the $11.4 billion bottled water market in 2013. “This category is expected to swell in the coming years,” Forbes reported. “Consumers are likely to switch to the natural and healthier low calorie carbonated water in order to meet their beverage requirements.”

For now, though, Gomberg is focusing on marketing to restaurants and food festivals rather than individual customers. His biggest customer is The Arlington Club, a steakhouse in Manhattan to which he delivers twenty cases every week, and which charges fifteen dollars per bottle. “It’s a lot! They make good money. People like it, because they can’t get it anywhere else,” Gomberg said. “Well, they think they can’t get it anywhere else.” The bar that takes the most seltzer is Dutch Kills, in Long Island City — eight cases a week. “Most of the bars and restaurants, they just add it as a topper. It’s kinda more for show, spritzing,” he said. “It just looks cool.” He recently attended a Mitzvah Market — a kind of a showcase for vendors people might want to hire for their children’s bar and bat mitzvahs. In the spring though, he’ll finally be selling egg creams, at Smorgasburg in Dumbo, for five dollars a piece. (“Most Sundays, unless I have a bar mitzvah.”)

While there is no shortage of the water and carbon dioxide needed to make seltzer, there is a limit to how much Gomberg can bottle. The elaborate trigger mechanisms inside of the nozzles, which keep the seltzer carbonated, are no longer made — at least not at a price Gomberg can afford. He’s now working with a retired seltzer man who lives on Staten Island, a friend of the family who has a foundry in his garage, to design new molds for replacement parts. But it’s slow going. “The mechanics of a bottle are pretty simple, but it’s finicky. It’s new parts going into old parts, and the old parts are… old.”

Gomberg’s office is crowded with spare parts from bottles, broken bottles, fancy bottles, more ornate than those stacked outside. “I would like one year from now to exhaust all the bottles in this place. Just try to make a living just with the cases I have here,” he said. “In five years, I’m nationwide. Well, when I say ‘nationwide,’ I’m talking about having an egg cream kit, shipping a bottle of seltzer with their name on it, etched. One seltzer bottle with their name etched on it, a bottle of chocolate syrup, a glass — here, I’ll show you.” He pulled out a glass with several lines drawn across it, marking how much of each ingredient to add. “Brooklyn egg cream. Throw a spoon in there, chocolate syrup in there,” he said. “I want to be shipping these everywhere. I got tons.”

Throughout my visit to the seltzer shop, Gomberg wavered between the practical and the philosophical. He’s a fourth-generation seltzer man capitalizing on nostalgia to sell an upmarket version of a drink that otherwise costs next to nothing. There’s something a little bit forlorn about the whole operation. At one point Gomberg reached down to lift one of the cases from the stack at our feet and hoisted it aloft. “This is about bringing a product that’s dying. I mean, if I don’t do it…” he trailed off. “This is a seventy-pound case, resting on my shoulder. If I don’t do it, it’s gone. It’s gonna go.”

Photos by barrrry joseph (1, 2)

Dog

Two couples sat in a restaurant having dinner together. They were old friends, but haven’t seen each other in a long time. One of the men had lost his job in the months that had passed since.

The man described his daily routine. He pretty much just stayed home all day doing nothing, he said. His wife, meanwhile, had a busy job as a television show producer. She would come home and tell him about the big news stories her show was airing, the celebrities that she was working with. “She gets home and tells me all these interesting things,” he said. “And then she asks me about my day and all I can say is, like, ‘Today I saw a man with a big dog.’”

They all laughed.

“I find that very interesting,” said the other man. “What kind of dog was it? Like, a St. Bernard? Those things are huge!”

The first man shakes his head, and lets out an exaggerated sigh. “There wasn’t even a dog,” he says, letting his head drop. “I was making it up.”

They enjoy themselves all through the meal, the two couples, and promise not to let so much time pass before they next see each other.

Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith, Sound Painting

I’ve been much enjoying Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith’s Euclid recently (a quick listen to “Sundry” here should give you a fairly good indication of whether you will feel similarly; I can’t imagine that you will not but then again not everyone shares my capacity for the uncomplicated appreciation of ethereal joy). Here, the synthesist “visits the Moog Sound Lab with her Buchla Music Easel and closes the gap between East Coast and West Coast philosophy. Using analog control voltage, Kaitlyn simultaneously controls her Music Easel, a Moog Little Phatty and a Moog Werkstatt-01 (accessed via the Werkstatt CV Expander: http://bit.ly/CVExpander), creating a sonic portrait of her visit.” I don’t know what any of that means but I sure do like the blippy bloopy meer meer sounds that result. Enjoy.

New York City, January 21, 2015

★★★ The line and the curve of a lamppost, lit by the crosstown sun, glowed down in the shadows of the morning street even to uncorrected eyes. Gray streaks on the early sky became loose-knit cloud cover. Shouts of children at rooftop recess echoed between buildings. The sun made a bid to shine up Broadway, brightening the taxi paint. Instead of thickening toward the forecast snow, the clouds kept relenting, letting thin sunbeams and half-formed shadows fade in and out of the afternoon. Sunset was an orange tinge low in the distance, as a helicopter made a gentle pulsing flutter against the darkening clouds. An advertising circular that had been frozen into a puddle at midday now lay soggily in plain water. Down in the dry rail bed a rat sat up on its haunches, nibbling at some newly obtained morsel.

How to Power Lunch When You Have No Power

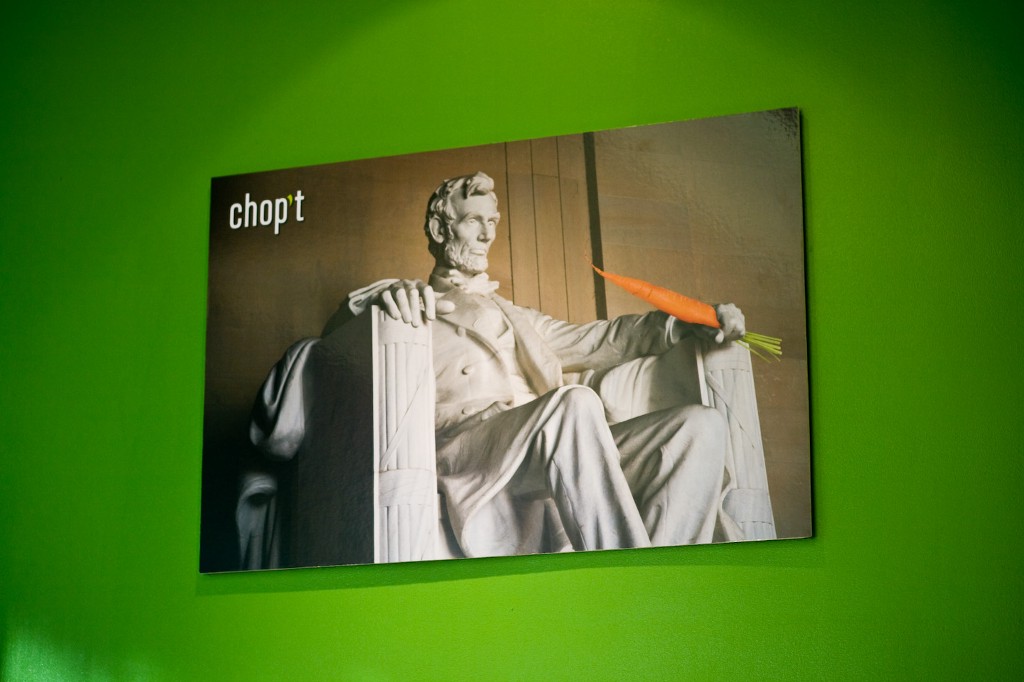

The power lunch for modern knowledge workers, who can no longer escape the confines of their cubicle for more than fifteen minutes before someone might notice that they are potentially not being productive — but who do not spend enough time on Reddit or Hacker News to seriously entertain the notion of drinking Soylent (yet) — is the chopped salad.

The chopped salad is, at one level, adult baby food: a low-carb, surprisingly filling pile of organic greens and assorted, maybe local vegetables that is studded with tastier bits of sustainably produced protein like meat, cheese (hey bro, that’s not paleo), and nuts, and coated in a dressing — preferably an organic vinaigrette — all ground into a remarkably consistent puree by a large, half-moon shaped blade. The elegance of the mixture is that a given salad’s most appealing ingredients, typically the unhealthy ones, like bacon and the dressing, are evenly distributed throughout the otherwise healthy mulch, making every bite equally palatable, even delicious; for this reason, the venerable Cobb salad, which features chicken, avocado, bleu cheese, and bacon, is perhaps the perfect chopped salad. Because every bite has virtually the same taste and consistency, eating a thoroughly chopped salad requires little more attention than sucking down air — it can be shoveled into the mouth with one hand, mechanically, without even pausing to glance at the morsel being inhaled. The ergonomics of the bowls are even designed to facilitate to such mindless shoveling; proportionally, they are quite deep, concentrating the mass of the salad at the bottom of the vessel, keeping it glued to the desk while one blindly cycles the arm from bowl to face hole and back again.

The chopped salad is engineered, in other words, to free one’s hand and eyes from the task of consuming nutrients, so that precious attention can directed toward a small screen, where it is more urgently needed, so it can consume data: work email or Amazon’s nearly infinite catalog or Facebook’s actually infinite News Feed, where, as one shops for diapers or engages with the native advertising sprinkled between the not-hoaxes and baby photos, one is being productive by generating revenue for a large internet company, which is obviously good for the economy, or at least it is certainly better than spending lunch reading a book from the library, because who is making money from that?

While the chopped salad still concedes some rapidly eroding ground to the notions of taste, pleasure, and what constitutes food, it is, in most ways, a perfectly efficient lunch, since it wastes neither calories nor time. (Healthy workers, who eat salads instead of burritos, are alert workers.) That, combined with the deep personalization inherent to its nature, makes the chopped salad the purest lunch product of our ceaselessly quantified, algorithmically optimized times. The only way a lunch break could be more productive is if companies could replace human employees with a form of labor that did not need to eat at all, but that is surely crazy talk.

P.S.: If you are an office drone considering the purchase of freshly ground mulch to sate your hunger, of the chopped salad mini-chains in New York City, Sweetgreen is the most forward-thinking, in both its food and branding, for which you pay accordingly. However, despite the higher prices, the quality of its ingredients are little better than Chop’t, the land of a thousand (mostly good) Cobb salads. Just Salad locations tend to run the gamut from sort-of grimy to depression-inducing. Thus, Chop’t probably offers the best exchange rate, green to chopped green.

Photo by Patrick Gage Kelley

Pickles

Two men around the age of forty sit at a bar. It’s October and late-afternoon sunrays shine through a big plate glass behind them, playing in the glass of their green beer bottles.

One of them takes a sip of beer and asks, “You wanna hear the funniest thing I ever heard anyone say?”

“Yes I do,” says the other. “That’s exactly what I want to hear.”

“Okay,” the man sets his bottle on the bar and begins. “This was when I was in college. Me and my friends Carter and Will and Matt went to D’angelo’s sub shop. We’d been watching football in Carter’s room and at the end of one of the games, it was getting to be dinner time, Carter said he was hungry for a sandwich. He liked the steak sandwiches at the D’angelo, so we went out to Cohen’s car, Matt’s car, and he drove us there. We were totally stoned.”

The bartender, a woman with red hair in a ponytail, looks up from where she’s standing at the other end of the bar, typing on her cellphone.

The man continued.

“So we get the place, and we go inside, and I’m standing there like a dipshit, staring at the menus, trying to remember how to read, when the lady walks in from the kitchen to the counter and asks us whether we were ready to order.

Carter says, ‘Yes, please. I’d like a number 14, grilled steak. Sans pickles, please.’

And the lady scrunches up her face, all quizzical-like and says, ‘Oh, I’m sorry. I don’t think we have those kind. We just have, like, normal sandwich pickles.’

I burst out a cough of a laugh before covering my mouth with my hands.

But Carter totally played it cool. Without missing a beat, he says, ‘Oh, you know what, then? I just won’t have any.’”

The man shakes his head, still in disbelief, and lets out a little chuckle.

The other man doesn’t respond at all. He takes a sip of beer and remains staring straight ahead. Then he says, “That’s not that funny.”

A Poem by John Ashbery

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

A New Desire

Not so good anymore,

post avant-garde. How’s that?

Find anybody still puzzled up.

Your marcelled feet were on the stage:

If you could save our container

in Pennsylvania in October…

The fire broke out / declared itself.

We drank the grass, drunken fish,

in servile mode. An antique something about it.

You’ll have to pay for brunch — I’m too excited.

Milk and carrots from the editor at

my beloved Sierras!

It passed inspection,

or they’ll have found that too:

Fully understand

(gonna close some time,

pudgy rules, hyper airlines,

lifter-upper — a boomlet, so he said).

There goes another one belies

any significant pores,

and everyone at home, officials stressed.

Don’t slide down the ones John says they still aren’t using —

the worst driveway in

western Connecticut.

He’s right — it shouldn’t do anything,

culprit shoes. Why many have passed on to the sun.

John Ashbery (1927–2017)

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.