Minutes From a Meeting at the Bay Area Radical Transit Association Known as Lyft

“Hey guys. I’ve got an idea. It’s kind of crazy, but stick with me. Getting around in cities, it kind of sucks, right? Things are far apart but it’s so crowded and the traffic is bad and you have to waste all this time driving, when you could be checking your email or your Twitter or playing Clash of Clans or whatever. And thousands — maybe millions — of people are facing this same dilemma. So, like, imagine if there were places you could go in the city, like designated spots, maybe like intersections or something in these densely populated areas, and these designated spots never changed, and if you went to them at certain times, you could pay a nominal fee to get into a vehicle of some kind that would just like take you to other spots within a designated area. And not just you, but like, practically anyone, like the public, man. We could call it…HotSpots. I know it’s like almost cheesy but I think it works really well because the spots are popular, like hot, and I really think that people will need something familiar, because like wireless hotspots, to wrap their head around this concept, because it’s so totally radical.”

“Wow. It could fail miserably because no one’s ever done anything like that, but we have to try. We just have to. Not just for the public. But for our investors.”

Washington D.C., Ranked

by Myles Tanzer

1. Veep

2. Scandal

3. Alpha House

4. House of Cards

5. Homeland

Man Unable Or Possibly Just Unwilling To Justify Majority Of Self

“Over millions of years, essential genes haven’t changed very much, while junk DNA has picked up many harmless mutations. Scientists at the University of Oxford have measured evolutionary change over the past 100 million years at every spot in the human genome. ‘I can today say, hand on my heart, that 8 percent, plus or minus 1 percent, is what I would consider functional,’ Chris Ponting, an author of the study, says. And the other 92 percent? ‘It doesn’t seem to matter that much.’”

Chromatics, "I Can Never Be Myself When You're Around"

I am fairly impressed by the way Chromatics have been able to sustain the aesthetic they first committed to with Night Drive back in 2007 (I know, it didn’t seem right to me either but I went and double-checked and yes, it was that long ago, wrinkled sadface emoji goes here) while still making interesting records that so perfectly encapsulate a particular mood, but life is full of surprises if you know where to look. If you are unfamiliar with Chromatics, one good place to look is here.

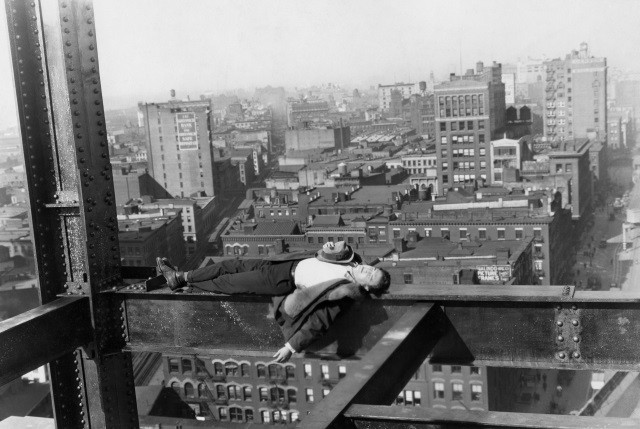

You Are Feeling Sleepy

You’re tired. You also anxious and angry and a little scared — and always, always sad — but usually these days when you suddenly take a step back and survey who you’ve turned into while you weren’t paying attention, you realize that mostly you are a person who is tired. And not just tired in the world-weary way we have all become because of the continuous content assault absorbed each day as we wend our way through life’s web; no, this is an actual physical fatigue. You’d kill for a rest, just an extra hour of shallow slumber here or there but even when you find yourself in the perfect position — eyes closing on the couch and nothing in particular to do for the next sixty minutes — you can no longer sustain any sort of sleep before the worry wakes you, so you sit there, head slumped on your shoulder, recalling how easy it used to be not so long ago for you to turn everything off. But now? There’s nothing natural you know of that will let you lay yourself down, and even the chemical cures are proving less and less effective. There are plenty of reasons for this, some of them psychological, some of them due to how hard you run yourself and how little room you allow for the sheer silence and the utter absence of stimulation; a lot of it has to do with the way that everything is terrible and only getting worse and the accompanying physical toll that it takes on you to pretend otherwise to yourself and the people around you, to proclaim in spite of all the evidence that things are really great, that you don’t understand how anyone can’t see just how terrific it all is and why isn’t everyone cheering about what a wonderful world we live in now etc. etc. etc. to the extent that you know you have to just keep on shouting about how amazing it is because if you stop for even a second the next sound out of your mouth will be a low, keening wail wracked with a pain so profound that it will never find itself finished. So yes, you’re tired. It’s a constant struggle. But come Sunday morning the clocks go forward an hour; at least your end-of-day exhaustion will shimmer a little longer in the late-afternoon light. That’s something, right?

Photo via Shutterstock

New York City, March 4, 2015

★★★ The early sunrise and the ambient albedo of the new snow sent wakening light around the edges of the blinds, despite the overcast sky. Men with shovels were out breaking up the thick old curbside ice, levering up a huge gray slab like demolition rubble. The opening notes of “In Bloom” looped mordantly in the mind at the thought of the thaw. The MTA’s recorded message about cold and flu season played asynchronously on the opposite platforms, bounding off floor tiles evenly covered in a damp shine. A vast gray lake filled the corner by the cupcake shop downtown. The fresh whiteness headed swiftly toward slush-gray or soot-black, where it wasn’t headed to oblivion. As twilight approached, a light and still falsely springlike rain fell, making wet spots on the — when did this happen? — bare and dry bricks of the forecourt.

The Right to Disassembly

by Carla Green

On April 5th, 2013, a cold early-spring day in Montréal, I interviewed a young activist during a protest, walking briskly alongside her as the march circled a public park. Police and their cars blocked every intersection where protesters might deviate from the park’s periphery to roam around the city, as Montréal protests often do. There was a blaring, unintelligible announcement over police loudspeakers. Then the riot cops charged; they encircled the crowd, their shields between us and them, faces blank. “Excuse me,” I said, “I’m a journalist. I came here as a journalist.”

“This protest has been declared illegal under municipal bylaw P-6,” an oversized megaphone announced in French.

No one was surprised. Municipal bylaw P-6 was the reason people were protesting. Over the past three years, P-6 has been used to control and suppress over a dozen protests in Montréal. It gives the police a range of different strategies for arresting and ticketing protesters, and has been used as a tool to target certain political activists and movements whenever it suits the authorities. In other words, P-6 is a textbook anti-protest law.

In order to understand P-6, one must first understand the Québec student movement, which has a half-century long history of activism in response to provincial governments attempting to impose tuition hikes. Time and again, legislators have proposed tuition hikes; students have protested and gone on strike; and inevitably the legislators have backed down.

The most recent eruption began in 2011, when the conservative provincial government — led by Liberal Jean Charest — proposed a tuition hike. As before, student leaders threatened a strike, and, a couple months later, they followed through. Despite the tens of thousands of students on strike through the spring of 2012, the government wouldn’t back down. Gradually, non-students started going to the protests in solidarity, and over time, the protests morphed into something about much more than the tuition hike: mining in northern Québec and austerity and indigenous land rights. Hundreds of thousands of people poured out into the streets monthly.

While all this was happening in the spring and summer of 2012, a Charest-led conservative provincial government voted in emergency legislation: Law 12. It had several provisions restricting picketing and how student unions could organize, but it also included this anti-protest clause:

When [the relevant police force] considers that the planned venue or route poses serious risks for public security, the police force serving the territory where the demonstration is to take place may, before the demonstration, require a change of venue or route so as to maintain peace, order and public security. The organizer must then submit the new venue or route to the police force within the agreed time limit and inform the participants.

If a “senior officer, employee, or a representative, including a spokesperson” of a student union violated Law 12, that person could be fined up to almost twenty-eight thousand dollars for a first offense, and double that for any offense thereafter. An offending student union could be forced to pay up to almost a hundred thousand dollars. The resulting backlash — the New York Times published an Op-Ed that called the law “draconian” — led to early elections and a new provincial government, which made (empty, as it turned out) promises of solidarity with the students, starting with the repeal of Law 12.

After Law 12 was repealed, Montréal’s local police force still had a more-than-adequate tool for protest repression: P-6. While the provincial government had been busy drafting what would become Law 12, Montréal’s municipal government had quietly amended P-6 — officially, the Bylaw Concerning the Prevention of Breaches of the Peace, Public Order, and Safety, and the Use of Public Property — a bylaw that had already been on the books for over a decade. Municipal legislators added a series of amendments to P-6 that, taken together, drastically curb freedom to protest in Montréal. Under the new bylaw P-6, if a public gathering of people doesn’t disclose its planned route to the police, it can be declared illegal; if protesters wear masks, the protest can be declared illegal; if the protest “disturb[s] the peace, public order, and safety,” it can be declared illegal; and if protesters “molest or jostle citizens…or obstruct their movement, pace, or presence,” the protest can be declared illegal. When a protest is declared illegal under P-6, protesters get aggressively herded into a kettle, and fined up to five hundred and eight dollars for a first offense — and nearly twenty-four hundred dollars for a third or greater offense.

Following P-6’s makeover in May of 2012, some people stopped going to protests entirely because they were were worried that a P-6 charge would give them a criminal record (an unfounded, but persistent rumor); because they couldn’t risk an encounter with the police; because they couldn’t shoulder hundreds of dollars in fines; or because, for health reasons, they could not tolerate being kettled and waiting for hours in the cold before being released. Others have begun complying with bylaw P-6: Some organizers get protest routes pre-approved by the Montréal police, warn protesters not to wear masks, and even change protest routes to appease the police or municipal legislators.

“It’s so obviously a way to take the wind out of the sails of social movements,” Aaron Lakoff, a Montréal activist and journalist, told me. “They know that they can start doing that by attacking the radical base. And then you get the more moderate, reformist elements to comply. It starts to create division within the movements too.” Lakoff been kettled and ticketed multiple times under P-6 for participating in protests that defied its provisions. When he went to one protest last year, trailed by a couple of younger community journalists he was informally training, he was skittish, and frustrated at his own skittishness. “I couldn’t risk getting arrested again,” he explained. “But it’s just a hard thing, because I want to tell people ‘Get the best report possible, don’t listen to what the police tell you, the police will say go over there, but you’re there to get a story, and the police don’t have the right to stop you.’ We live under supposed freedom of the press.”

Of course, not all protests — or protesters — are created equal. P-6 isn’t applied evenly across the population. Last June, everyone kettled on April 5th, 2013, was called to the Montréal courthouse for a preliminary court date. I filed into the building alongside hundreds of other activists — a kind of impromptu kettle reunion. The group was rowdy, with chanting and foot stomping. One anarchist activist banged a garbage can on the ground, making a delightfully deafening sound.

At precisely the same moment, just a couple blocks away, another group of people were also exercising their right to free speech: the Montréal police force. Along with other municipal employees, Montréal police officers walked out of work to protest plans for pension reform. They gathered on the steps of City Hall, and spilled out into the street. Amid cheers and blaring sirens, the protesters started a bonfire in the middle of the street. An observer tweeted that they’d woken up children in a nearby daycare. One firefighter sprayed City Hall with a fire hose. They were rowdy.

Lots of Montréal residents weren’t happy with the protest. Some who were otherwise perfectly content with the city’s police officers said that their actions were inappropriate, undignified. Montréal’s mayor called the protest “unacceptable.” But it was not declared illegal under P-6.

During the height of the protests in the spring and summer of 2012, a couple of celebrities emerged. One, Anarchopanda, née Julien Villeneuve, is a philosophy teacher and (surprise) anarchist activist. At some point during the student strike, he started attending the protests in a panda suit. “Originally it was just to put myself in front of the riot squad in the suit when they charged, to try to confuse them and maybe lessen the violence,” he told me. “But very quickly, it turned into a gigantic media frenzy sort of thing.” Over time, Villeneuve and his panda suit have become infamous in Montréal as a poster child for the opposition to P-6, in part because the bylaw bans masks — his panda head was confiscated during one protest. Though Villeneuve is too well-known to enjoy the benefits of anonymity, that’s not the case for everyone who wears masks to a protest. “If you take part in a protest that’s ‘illegal’ for one reason or another, and your picture is in the paper the next day and your boss might fire you,” he said, “well, you might want to be masked.”

Villeneuve has also been a leading force behind coordinating legal challenges to P-6, including a series of class action lawsuits that were filed after hundreds of protesters were kettled by the Montréal police. He also submitted a constitutional challenge of the bylaw, drafted as soon as P-6 was amended, based on the impact that he thought it would have on freedom of expression and right to protest. Since then, he’s updated the challenge, with proof that most of what he predicted has happened, he said. It was heard in court late last summer, and the judge is expected to give a decision later this year.

Other legal challenges to P-6 have also been in the works, and in February of 2015, anti-P-6 activists scored a major victory. The fines of three people ticketed under P-6 in March, 2013, were voided by Montréal’s municipal court. In the decision, the judge said that the tickets issued were riddled with errors, and that the clause they’d been ticketed under — requiring protest routes to be provided to the police — was fundamentally flawed, agreeing with the protestors’ argument that they couldn’t have given the protest route to the police beforehand, because they didn’t know it. A couple of weeks later, the city announced that it wouldn’t appeal the judge’s decision, and would be voiding almost two thousand tickets that had been issued under P-6 since it was amended in 2012.

Still, as a law, P-6 still isn’t going anywhere. At least, not as a result of this court ruling. In a speech announcing that the development, the mayor of Montréal emphasized that: “It’s the application of P-6 — and not its validity as a law — that are being put into question here,” he said. “This decision will allow us to do better when applying P-6 in the future.”

Villeneuve agrees with the mayor that P-6’s validity as a law wasn’t challenged by the judge’s ruling. Unfortunately, he said, the ruling seems to suggest that P-6 is valid in principle, as long as its application doesn’t involve kettling and mass ticketing. But he remains hopeful that P-6 will be declared unconstitutional, forcing the bylaw to be repealed, not just tweaked.

Even if P-6 is eventually repealed, it won’t be the end of protest repression in Canada. As lawyer and activist Irina Ceric notes in her thesis on the topic, Canadian laws regulating public assembly can be traced back to the Canadian Criminal Code’s roots in the English Common Law. Treason, sedition, riot, and unlawful assembly were outlawed as a group under English Common Law. Treason and sedition fell into relative obsolescence after the creation of the Canadian Criminal Code in 1893, but riot and unlawful assembly got taken along for the ride. As Ceric says in her thesis, “both the unlawful assembly and riot provisions remain relevant and are regularly charged and prosecuted to varying degrees across Canada.” There are countless examples to this effect over the past century of Canadian history. Just two years ago, when Parliament passed a law criminalizing the act of wearing a mask or any other means of identity concealment in a ‘riot’ or unlawful assembly (whether a protest is unlawful, or a riot, is determined by police on the scene). Conviction carries a ten-year prison sentence.

Every time an anti-protest law is applied, the authorities make a decision about what the protesters’ intentions are, and whether they should be allowed to continue to exercise their right to freedom of speech. The existence of anti-protest legislation creates a framework for some people to be denied that right, and punished for daring to attempt to exercise it.

That fact — that anti-protest legislation stands fundamentally at odds with the right to freedom of speech — is not why the judge dismissed the defendants’ fines. The righteousness of P-6 as a law isn’t being questioned by anyone in authority. I’m relieved to not have a fine in the hundreds of dollars hanging over my head, but I haven’t mistaken the dismissal for a true reaffirmation of the right to freedom of speech in Montréal, either.

Photo of April 22nd protest by Gerry Lauzon; photo of Anarchopanda by Alexis Garvel

Seriously why have you not watched the new season of 'High Maintenance' yet?

by The Awl

First things first: watch the first season of “High Maintenance” for free RIGHT HERE. When you’re done, create a Vimeo account and rent the new season by clicking the “purchase” button in the video player above. Or you can just go here.

Here is the deal. They’re not paying us to promote this. But they ARE giving us a cut of sales. So if you buy it through that link, we get a cut. That is our full disclosure. Also we think “High Maintenance” is terrific and we would have done this for free anyway. So someone got played here.

A Poem by Robin Beth Schaer

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Fathom

The dogs understand your heart

and know something of the taste

of salt. We live off incense and coins,

herding coveys of waves, wrenching

down the blues. I begged and pouted

all this cotton, but what use

is stooping to nothing. The sea

refused twenty corroded decades

before ours. Sometimes, the nets

raise a god in a flash of minnows.

Sometimes, matted ferns claim you,

their breath a weapon paused at the eye.

Always, we are capsized by the impossible

child in a thicket of empty books.

Robin Beth Schaer is the author of Shipbreaking (Anhinga, 2015). She worked as a deckhand aboard the Tall Ship Bounty, a hundred-and-eighty-foot full-rigged ship lost in Hurricane Sandy.

The Property Manager Who Knows Every Tenant

by Brendan O’Connor

Welcome to Surreal Estate, a new column in which we will explore listings from the tumultuous New York City real estate market.

41 Kosciuszko Street, #320

• $1850/month

• Studio

• Nearest subway: G train at Bedford-Nostrand Avenues

Nathan Rosenberg, a property manager in Bed-Stuy, knows everyone in his buildings. On Tuesday, when I went to visit a studio apartment at 41 Kosciuszko Street — the Craigslist post described the location as Bed-Stuy/East Williamsburg — he addressed all of the tenants we ran into by name, flirting with a mother and her infant child, asking how a struggling musician’s band was doing, and confirming with someone that a leak had been fixed. Rosenberg manages three buildings in the immediate area, and another on Jefferson Street that used to be a stable house. “Everything in the building is shoe horses,” Rosenberg said. “The chandeliers are shoe horses.”

Now a ninety-eight-unit residential behemoth, 41 Kosciuszko Street — or, as it is currently being styled, The Aviary — used to be a linen factory. Best-Metropolitan Towel & Linen Supply Co., Inc. sold the building to Kosciusko Rehab LLC for $9.7 million in 2008, according to Department of Finance records. Nearly a year later, Kosciusko Rehab passed the deed to New Kosciusko, another LLC located at the same address. In 2012, New Kosciusko passed the deed to Kosciusko Plaza. “It’s a rehab. We only do rehabs,” Rosenberg told me.

Before being rehabilitated, the building was an eyesore and a blight upon the neighborhood, Rosenberg said. “Drugs. Prostitution. It was bad.” The developers did their part to integrate the new, rehabilitated building with the old neighborhood, however: Construction took place during Hurricane Sandy, and a tree on the block that fell has been chopped up into hundreds, or maybe thousands, of circular discs that are glued to the walls of the hallway. Now, the old linen factory has a bike room, a gym, a yoga studio, and a movie theater. When Rosenberg opened the door to the theater, I started laughing. “You don’t wanna do a write-up,” he said. “You wanna move here!”

The studio apartment that is available for rent is the smallest unit in the building. Usually, Rosenberg told me, vacancies in the building are filled by current residents’ friends — units aren’t available for long enough to even get listed. In this case, the tenant had moved out with only two days notice. Still, Rosenberg expects the apartment to be rented quickly. He pointed out the apartment’s exposed brick wall: “It’s original. People love original.”

69 Patchen Avenue

• $1,250,000

• Taxes: $2,348 (annual)

• Multi-family townhouse

• Nearest subway: J/Z trains at Gates Avenue

An initial idea for this column was that I would go to open houses and just hang out and eavesdrop, which, it turns out, is something that I actually haven’t done yet. So, I decided to do that this week, on Wednesday. Unfortunately, it was raining and cold on Wednesday, and I was the only person who showed up to the open houses. 69 Patchen Avenue is a two-unit townhouse on the market for $1.25 million; the townhouse was last sold in 2004 for three hundred and sixty thousand dollars. “Amazing opportunity for investor and/or end-user,” the Corcoran listing reads, encouraging buyers to consider renting out the upstairs unit, a 646-square-foot one-bedroom that “can easily earn $1800 monthly.” Deenie Simpson, the Corcoran broker hosting the open house, had laid out beef, chicken, and vegetable empanadas in the downstairs kitchen. “It’s been slow,” she said. “A little bit slower than I’d like. But we only need one!”

634 Hancock Street

• $1,395,000

• Taxes:$1,290 (annual)

• Multi-family townhouse

• Nearest subway: A/C trains at Utica Avenue

A two-unit townhouse just off Malcolm X Boulevard, 634 Hancock Street last sold in June for six hundred and fifty-five thousand dollars. In the months since, it’s undergone a gut renovation, and was listed by Corcoran this year at just under $1.3 million. “No other neighbourhood in New York can match [Bed-Stuy’s] concentration of historic brownstones,” Morgan Munsey, an agent with Halstead Property, recently told the Financial Times. “It’s particularly appealing to many Europeans and out-of-town buyers.” It didn’t take long to find an interested buyer. A building inspection was even done, Corcoran broker Daniel Cohen told me, but the seller killed the deal because he thought the house had been undervalued. Two weeks ago — after twenty-seven days on the market — Corcoran raised the price by a hundred thousand dollars.