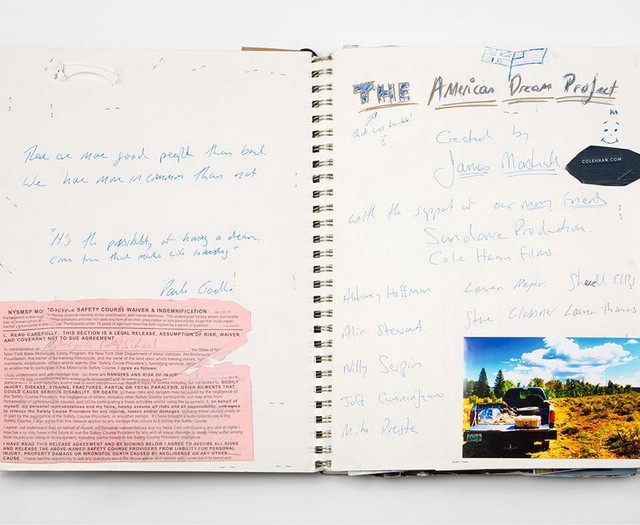

The American Dream Project

by Awl Sponsors

Brought to you by Cole Haan and Happy Marshall’s American Dream Project

.

What is the American Dream? Is it still alive today? And if so, who for?

Every day we are bombarded with bad news — about jobs, debt, climate change and the vanishing middle class. We worry about the things that divide us. But how often do we hear stories of the true spirit of everyday Americans?

It feels like the American Dream is still an open question.

James Marshall explores this theme in his American Dream Project — a multi-part series documenting a cross country motorcycle trip from New York City to Los Angeles. James and his friend Todd Williams took off armed with just $250, their wits, and a sense of adventure. Their journey was guided by a single aphorism: “There are more good people than bad. We have more in common than not.”

James’ objective was simple: reverse the negative sentiment Americans and the media are (more often than not) associating with “America.” By using social media to connect with people, plot their course, put a roof over their heads at night and work for their keep, they were able to document and showcase that The American Dream and the optimistic spirit that built this country is very much so still alive. Check out more stills from the journey below.

Watch the American Dream Project series here.

Episodes of Eating Children in Ancient Greece, Ranked in Order of Unreasonableness

by Summer Block Kumar

5. If anyone has ever had a good reason to kill and serve their own child for dinner (they haven’t), Procne did (even though she didn’t). After Procne’s husband, Tereus, raped her sister, Procne took revenge the only way ancient Greeks knew how: She killed their son, Itys, and fed him to his father. According to the myth, at some point during the meal, Tereus said, “Hey, where’s Itys? We should have him here with us,” lobbing Procne the best straight man line in ancient history.p

It’s worth noting that Procne was the only child-server not punished by the gods for her actions; to aid their escape from Tereus, Zeus turned her into a swallow and her sister into a nightingale. Being turned into a bird is perhaps ambiguous — reward and punishment — but it mostly depends on the type of bird.

4. Atreus was angry at his brother Thyestes for many reasons, including sleeping with his wife and trying to steal his throne through an absurd wager involving a golden sheep, which was perhaps the dumbest ruse in ancient history.

To get his revenge, Atreus murdered Thyestes’s two sons and served them to Thyestes at a banquet. Wikipedia assures us, “This is the source of modern phrase “Thyestean Feast,” or one at which human flesh is served,” though a Google search for the phrase “Thyestean Feast” mostly turns up references to a now-defunct black metal band of that name from Finland.

Much grief might have been spared had Thyestes kept in mind this simple trick: If you must attend a banquet thrown by your greatest enemy, keep a close and constant visual check on your children at all times immediately before, during, and after the meal.

3. The elder god Cronus decided to eat his own children as a preemptive strike, having learned that they were destined to someday overthrow him as he had overthrown his own father, Uranus. Father to Demeter, Hestia, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon, Cronus ate each immediately after they were born, because better safe than sorry. However, his wife Rhea managed to save his youngest son, Zeus, by replacing the baby with a stone wrapped in a blanket, which Cronus swallowed instead, because Cronus was not a details guy.

Many foundational myths exist to reinforce cultural values or to impose restrictions on antisocial behavior. The fact that Greek myths were constantly teaching the same lesson about not eating your kids betrays a real societal fear that everyone would eat their kids at the drop of a hat if not explicitly and repeatedly warned otherwise.

2. This is hands-down the worst reason to eat a kid. Tantalus, Zeus’s loser son, decided to kill his son Pelops and serve him to the gods to test whether or not they were really omniscient.

The important thing to understand here is, Tantalus could have done literally anything to test whether or not the gods were omniscient. He could have asked them to guess how many jelly beans were in a jar. He could have challenged them to a game of three-card monte. He could even have cooked someone else’s kid.

This is proof that killing and eating your kids was the go-to solution for problem-solving in ancient Greece. Tantalus looked around for something he could chop up and put into a casserole and the first — the only — thing he thought of was his own son. When all you have is a hammer, I guess.

1. Lycaon also served a child (his grandson, Arcas) to a god (Zeus) to test if he was really omniscient. So that happened twice. Zeus didn’t fall for it, not because he is omniscient, but because around Mount Olympus this was already a completely hackneyed trick. “Made you eat your kids” was the “your shoe’s untied” of the ancient world.

As punishment for his embarrassing party foul, Zeus murdered Lycaon’s fifty other sons, which doesn’t seem so terrible considering how disposable Lycaon considered his sons to be, and then turned him into a wolf, which also doesn’t seem so terrible, because wolves are cool.

Brother John Is Gone

“’Scar’ John was a special cat. He saved my life one time. We were standing outside the Robin Hood Club listening to Little Miss Cornshucks when he suddenly said, ‘Look out, man.’ So I looked out and half a St. Louis brick came sailing past my head.”

— This piece on the origins of the Neville Brothers’ “Brother John/Iko Iko” is worth reading if you are someone who correctly acknowledges the song’s genius. And most of it is understandable even to those who were not dodging bricks outside of clubs in early ’70s New Orleans.

The Dudes in the Machine

“I get the ‘moment’ you’re having,” Ex Machina’s wonderfully patronizing search engine potentate Nathan Bateman tells his starstruck employee and guest, Caleb Smith, when they first meet in Bateman’s secret Alaskan lair, a modernist palace hidden in a vast, pristine forest. “But can we just get past that? Can’t we just be two guys, Nathan and Caleb, let the whole employer-employee thing… go?”

But Batemans never intend to let the Calebs forget who’s boss. Ex Machina centers on the mucho macho power tripping of such men, and on the mirror-image power tripping of the beautiful young women to whom they are so inconveniently vulnerable. On the surface, writer and first-time director Alex Garland’s movie is about hubris, power, and control, and though it will be tempting to dismiss Ex Machina as a kind of nihilist Weird Science wallpapered over with intellectual pretensions, Garland also genuinely grapples with ideas about artificial intelligence and technology. And a movie of ideas is somewhat rare in itself lately — plus this one is enchantingly beautiful to look at. This remains true even though Garland’s premises, if you make the mistake of taking them too seriously, will eventually land you in a sterile, well-designed place of total dumbness about everything from the gender wars to the future of robotics to the hive mind. Wheee!

Oscar Isaac, a movie star if there ever was one, is splendid as Bateman, the weirdo Internet CEO genius behind Bluebook (Google, more or less, under a fatuously Wittgenstein-derived name. I mean it is okay I guess to suggest that gathering intelligence about language from the hive mind kind of jibes with Later Wittgenstein? But these self-serious flourishes end up stripping away the veneer of seriousness they’re intended to impart.) Bateman is a “mad scientist” in the classic mold: menacing, charming, with a fantastic frisson of Silicon Valley clueless-rich-bro arrogance; Garland most definitely knows his rich people. Caleb, a hotshot Bluebook programmer, has won a contest to spend a week with the boss. Soon it emerges that Caleb has a job to do: administer the Turing test to a walking, talking sex toy, the luscious, if see-through, Ava. She is half inflatable doll (“you bet she can fuck”) and half mad-science experiment, and Caleb doesn’t even think to question why Nathan made her. She’s an Apple product, and he’s a fanboy:

Nathan: You’re going to be the human component in a Turing test

Caleb: Holy shit!

Nathan: Yeah, that’s right Caleb! You got it! ’Cause if that test is passed, you are dead center at the greatest scientific event in the history of man.

Caleb: If you’ve created a conscious machine, that’s not the history of man. That’s the history of gods.

And yet if Garland poses a set of fascinating questions around the why of it, it’s tangential to the love-and-power triangle presented in the plot: Who of the three will come ex machina, “out of the machine”?

Like Maria in Metropolis and Number Six in Battlestar Galactica — artificial women — the glorified dolls of Ex Machina turn out to be more complicated than anyone (usually men) gave them credit for. Not only might they have their own ideas, they might have their own secrets; not only might they have a will of their own, they might be capable of furthering their own interests. Fun as it can be, this conceit is in no way here advanced even to the point reached by Blade Runner in 1982. Garland means for you to sympathize with Frankenstein’s Fembot, simultaneously condemning her objectification even as he is participating in it — he’s having his cheesecake and eating it too. Evidently the Sensitive Men will be mansplaining forever about how women are more complex — even dangerous! — than they may appear. People respond in an irrationally positive manner to beautiful young girls, you may be surprised to learn. And that makes them even more powerful! Also: Women may not take kindly to being objectified, did you ever think of that?

But where Ex Machina really comes alive is in its scientific ideas: For instance, if an artificial intelligence could be informed by the collective information, thoughts, and emotions of everyone who uses or has ever used the Internet, what would the result be like? There’s a wonderful part where Nathan allows Caleb to examine the “wetware” brain he designed for Ava (a term, by the way, that Garland did not coin. It’s super old!) Where does the software come from that operates this beautiful glowing blue blob, this computer brain that has given Ava consciousness? “Bluebook,” Caleb breathes. That part is so neat! As for the potentially benign AI: after enduring decades of Skynet and variations thereupon, I was so refreshed and captivated by this old-fashioned notion that The Machines might turn out to be noble, after all! Ex Machina proposes, if glancingly, the possibility that an AI might be not only worthy of real love, but also capable of giving it on her own — making it out of whole cloth, as it were. Not even Data could quite do that.

There is one interesting question about all this (given especially that Isaac so closely resembles Garland physically): Bateman feels that his intelligence qualifies him to seize and wield power and control over others — he’s not afraid of Ava or her sexuality, he has a right to dominate her. But, the movie is saying, maybe he should be afraid. What does that say about the quasi-libertarian power-seizing mindset of today’s real technocrats? And what does it say about movie directors?

This is Garland’s debut as a director, the latest achievement in a brilliant and eclectic career that began at age twenty-six with the bestselling debut novel, The Beach, which was made into a film starring Leonardo DiCaprio. He wrote the screenplays for 28 Days Later, Sunshine and the adaptation of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. He told the Guardian that he feels more strongly about this film than about anything else he’s done so far. It’s his story, his direction, his designs — it’s an auteur piece from which one comes away with the idea that this auteur wants very much to be “taken seriously.”

In an interview posted last weekend, Garland told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “I know it’s not politically correct, but this is true — some people are smarter than others. Now, smart people don’t enslave stupid people. We know that’s wrong. There might be some evil bastards that do try it, but as a rational society we don’t accept that.” These assertions go a long way toward explaining Ex Machina’s deficiencies. If you are willing to believe the blobby, incoherent proposition that “some people are smarter than others,” it will be a lot easier to swallow Garland’s story, with all its improbabilities (and, ultimately, the contradictions of the auteur’s proposition regarding “intelligence.”) The characters are all trying to “outsmart” one another — there’s all this cleverness, as each tries to gain advantages, secret and explicit, over the others — but the real drama takes place in the larger context of the potential costs of our growing reliance on technology, and our own increasing isolation and vulnerability. When you sacrifice human values and contacts to pushing the envelope of technology, and business ambitions, all that cleverness comes at a cost. The familiar Frankenstein story. But now that we can see the real-life means whereby human beings might create life, or something like it, that old story has taken on an entirely new gravity.

Garland comes from a distinguished family — his mother is psychoanalyst Caroline Medawar Garland, and his father the cartoonist Nicholas Garland, illustrator of Barry Humphries’s Barry McKenzie in Private Eye. His grandfather was Sir Peter Brian Medawar, the Nobel-prizewinning zoologist and author. He was kind of the Atul Gawande of his day, only far more eminent — he pretty much founded the whole field of organ transplantation, and as if that weren’t enough, he was a noted disciple of the philosopher Karl Popper, as well as being a handsome, tall, elegant and gloriously witty writer, a popularizer of science whose collected essays, The Threat and the Glory I can recommend unreservedly.

(Interestingly, it was Popper who was threatened with a poker by Wittgenstein at Cambridge in 1946 during an argument over whether or not there are philosophical problems, an episode admirably recounted in the walloping 2001 bestseller, Wittgenstein’s Poker: PLEASE read this book if you haven’t yet.)

In his 1960 Nobel acceptance speech, Medawar talked about biology’s ability to produce altogether new kinds of understanding:

[T]hough our brothers of physics and chemistry may smile to hear me say so[,] biology is now a science in which theories can be devised: theories which lead to predictions and predictions which sometimes turn out to be correct. These facts confirm me in a belief I hold most passionately — that biology is the heir of all the sciences.

In other words, the fundamental problems of biology — its mysteries, if you like — are complexities to be learned from from, not merely to be “solved,” as Garland’s protagonist Nathan Bateman, and all our real techno-utopians, would have us believe. Writing on the Royal Society website, Neil Calver described the chief insight Medawar took from Popper: “recognition that human designs and human schemes of thought are very often mistaken and that the safest way to proceed is to identify and learn from mistakes.” This isn’t the “fail fast” philosophy of today’s Silicon Valley technocrats, but a patient and careful concern with “the safest way to proceed” — a recognition of the value and difficulty in making the progress already made, and a corresponding reluctance to press forward thoughtlessly. That mistakes are all we are made of, and that empirical progress must always and ever depend on that single certainty, is a most valuable insight, but not one you will get from watching Ex Machina.

Total Babes, "Blurred Time"

A big pleasing brick of sound to club you through the last day of the week.

New York City, April 22, 2015

★★★ A fine bright morning showed no signs of the trouble forecast to come. A window washer had swung open the glass walls of the near-finished apartments across the avenue and working was out on the bare concrete ledge. The slender stems of the lights along the top of a billboard laid long, conspicuous strips of shadow diagonally across the image. The sky stayed flawless into afternoon — then, abruptly, it wasn’t. Lumpy dark gray came in from the west. A piebald pigeon with a white face and white wings mounted a regular pigeon-colored pigeon by the edge of a roof. When it was done, it flew off with a slow clapping sound. The sinister gray receded, briefly, and then it was back again and raining. By rush hour the rain seemed to be over downtown, but uptown it was falling again. Finally it yielded for good, to a wash of late light and a gaudy sunset.

The Box Builder

by Brendan O’Connor

508 West 24th Street, Penthouse South

• $9,250,000; common charges: $4,246; taxes: $2,041

• 3 bedroom; 3.5 bathrooms

• Interior: 3,018 square feet; exterior: 600 square feet

There are three penthouses in architect and developer Cary Tamarkin’s newest West Chelsea building, on West 24th Street. Penthouse North is already under contract. All of the other units in the building have been sold as well, and the ground floor retail space — sold to an investor — has been leased. Tamarkin’s buildings, with their boxy, post-industrial outlines, are scattered across the West Village and Chelsea, where many less graceful imitations have sprung up as well. Tamarkin “is widely credited with having reintroduced the fashion for raw-space loft development in New York,” the Times wrote in 2001.

On Tuesday, listing agents at 508 West 24th Street were holding an open house for brokers to see the two remaining penthouse apartments. One visitor had apparently been involved in a landmarking dispute with Tamarkin on the Upper East Side in the early aughts. Tamarkin’s initial proposal had called for a seventeen-story condominium building; the building plan that passed, two years later, was nine stories. “Tell her I hate her,” Tamarkin scoffed.

Tamarkin, who is from Long Island, studied architecture at Harvard and led his own firm, in Boston, for ten years, before moving back to New York in the early nineties to become a developer. “My whole life I had identified as an architect. That’s what I did since age twelve,” Tamarkin told me. “But I wasn’t prepared to be a starving artist my whole life.” In 1992, when he was thirty-five, he invested with a friend who, conveniently, had just gotten a job running the real estate fund at Oaktree Capital, in an abandoned warehouse in the West Village. A building at 140 Perry Street, which had been vacant for five years, Tamarkin said, cost 1.6 million dollars. “Even if the building made no money, I’d make twice as much money as if I’d just been hired as an architect, because I was also getting development fees,” he said. “In fact, the building sold out, and I made a million dollars. I had never seen a million dollars. So, this was definitely the right idea.”

Tamarkin’s first building in West Chelsea was 456 West 19th Street. “At that time, this neighborhood was scary to walk in at night,” he said. (That was in 2008.) “The High Line is this kind of museum of architecture. There’s everybody and all types, all different famous names in architecture, and all different architecture. Everybody’s got their own take on it.” This is not necessarily a good thing, as far as Tamarkin is concerned. “We don’t like to scream for attention in my firm. We like to do things well, and get attention. If everybody’s yelling, you can’t hear anybody. I just wanted a powerful, muscular building.”

508 West 24th Street, directly adjacent to the High Line, is made out of concrete — a first for Tamarkin. This gives it a very different look than most new constructions, which are heavily reliant on glass and stainless steel. “It’s not following current trends, I’ll tell you that much,” Tamarkin said. He nodded across the street. “HL-23 is one of these buildings that is super, uh, interesting. Flow-y, dancing, whatever it does. It’s totally not my thing,” he said. “I wanted it to be like a rock. As close to a rock as it could be.”

Out on the six-hundred square-foot Penthouse South balcony, Tamarkin noted another architect copying his signature look — banded, industrial windows. (Tamarkin admitted the influence of the hulking Starret Lehigh Building, visible from the balcony to the north west, on his own aesthetic. “It’s like a skyscraper laid on its side.”) “When I look back on my body of work, I didn’t set out to have a signature style. But if you’re an architect who’s thinking about what you’re doing, there’s going to be similarities between the buildings,” he said, before pointing to another building. “There you can see Robert Stern copying our windows. These windows are starting to show up all over the place. So I need a new idea.” And, in fact, he has one. “Clocks. I’m gonna put a clock on every building.”

508 West 24th Street, Penthouse A

• $12,500,000; common charges: $5,160; taxes: $2,480

• 3 bedroom; 3.5 bathrooms

• Interior: 3,318 square feet; exterior: 1,900 square feet

It is unusual for a developer to design his own buildings, a fact of which Tamarkin is well aware. “We’re architects as well as developers, so we play both roles.” (“People hate developers and they love architects, so they don’t know what to do with me,” he likes to say.) “There are very few people who do that. There’s no role model to follow, so it’s very confusing. But it ended up being fantastic! They don’t teach you in school that that’s an option — although now schools are asking me to come and talk to their real estate programs. But it’s such a different thing. You have to be really into business, and yelling a lot. It’s the opposite of architecture, which is very quiet.”

As an architect, Tamarkin likes to be able to visit his building sites with ease — which limits his options as a developer. “The architect part of me wants to be really close to the building site so I can go all the time and make sure it’s being done right. So that gets harder to do in Brooklyn. Even uptown, it gets harder to do.” (Tamarkin is currently renovating an old Catholic school on the Upper West Side.) “It’s a pain in the ass. I like to be within a few blocks of the office.”

“You also have to know the neighborhood,” he said. “When I’m working in the West Village, Chelsea, the client is me. So I feel like I know what to do. If you build somewhere else, even in New York — the Upper East or Upper West Side — you’ve gotta really familiarize yourself with all the competition, what people are building, what people want. It’s a whole different community.”

As for Brooklyn, Tamarkin said, “I look at stuff occasionally there, but I think I’m jaded by New York.” (By “New York” he meant “Manhattan.”) “Everything I see, in Williamsburg, in Greenpoint — it’s horrible. And you can sell for half as much as New York, so you have to build cheap to make money there.” He continued, “Given the opportunity to make money and build something shitty, it’s not interesting to me. Given the opportunity to build something beautiful and not make money — that’s not interesting to me either. It’s gotta be both.”

“I can’t imagine that there’s not a way to take those materials and make something substantial and beautiful, and I welcome that challenge. For real.” For real, for real? “I go look at stuff! I’m not not up for it. I just haven’t done it. This is a realm that I’ve designed in for my entire life, for wealthy, expensive people that want to do good stuff.”

“In terms of affordable housing, I believe in it all, it sounds — and is — great, it’s just not the stratosphere that I operate in,” he said. “I only really know how to do expensive buildings.” And yet, he added, “It’s not that I don’t believe in the stuff politically…I would like to take up the challenge.”

“I don’t necessarily want to do the same thing my entire life,” he said. “Although, maybe I will.”

A Poem by Stephen Burt

A Poem by Stephen Burt

by Mark Bibbins, Editor

Esprit Stephanie

The hard work of appearances disappears

into the apparent effortlessness, and the loose three-quarter sleeves

of trying to become what other

people, your friends, your real friends, are convinced that you already are,

like trying to follow the pale fleck of a small plane,

or a big plane far away.

Sweatshirts big enough to hide half a person

hide behind their modular words,

and leggings. Where two or three strangers gather

together, sandbar: we are migratory birds,

temporarily almost aloft, almost fluorescent, in a 1983

of lemon-yellow possibilities,

things I might very insistently wish to be.

Only an eyelash separates me from reason,

from the coveted role of pretty-to-geeky liaison.

To be good, to be

a good girl, is to pile up

credit you have to use up

before nobody else remembers you earned it.

There was a lesson in variability here, and in the history

of stencils, but I am not the girl who learned it.

When I got here first I looked around, and around.

I would like to compare my own growing up

to sand, and you and you to solid ground.

Stephen Burt is Professor of English at Harvard and the author of The Art of the Sonnet (2010, with David Mikics), Belmont (2013), and the chapbook All-Season Stephanie (out now).

You will find more poems here. You may contact the editor at poems@theawl.com.

The Only Good Apps: A Complete Guide

A video posted by @perfumegenius on Apr 22, 2015 at 12:55pm PDT

My Idol: Puts your face on a body that you can make dance (not in English)

Ditty: Sings the words you type

Morfo: Makes a hideous uncanny avatar out of your face, sings, moves

Face Swap!: Swaps faces, messes up a lot

Dubsmash: Dubs you with songs and other sounds, nobody looks cool doing it

Looksery: Changes your face in real time into an attractive person/lizard/demon/skeleton

YouNow: Live cams of people doing things but mostly sleeping??

Air Horn LOUD Free: Air horn, loud, free

AgingBooth: Makes you old like you’ll be when you die if you’re lucky

Flinch: Staring contest Chatroulette where nobody speaks the same language and you lose if you smile

Talking Pet Booth Free: Makes your pet say whatever you want your pet to say (I love you)

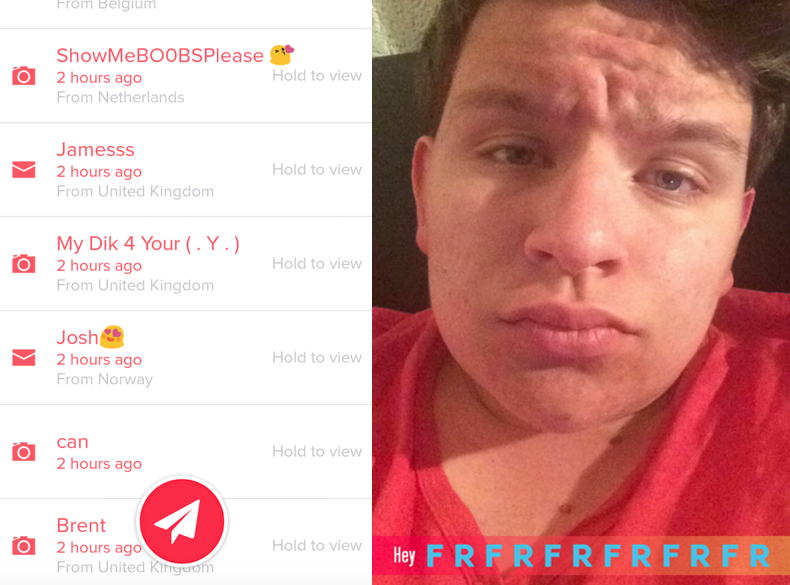

Fling: Sends messages to 50 random people around the world, including you, so it’s just a whole bunch of weird pics from people, lots of them are gross and terrible, more of them are just confused text and faces

Aillis (formerly LINE camera): Ultra mega maximalist Instagram

Crazy Heliumbooth Free: Funny faces and voices, good for both idiot adults and idiot babies

Congratulations! Now you have all the good apps.

Ken Camden, "Curiosity"

Ken Camden’s gradually accumulating blips are no ordinary gradually accumulating blips: he uses “a steel slide and e-bow technique… to bridge the textural gap between guitar and synthesizer.”